Abstract

Through the lens of social identity theory, this work aims to investigate the impact of servant leadership on employee resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic and to explore their underlying mechanisms through two types of social identity: organizational identification and professional identity. To test our hypotheses, an online survey was conducted via a large number of 703 employees working in public organizations in southwest China. Results yielded from the structural equation modeling analysis via AMOS (24.0) indicated that the effect of servant leadership on employee resilience was fully mediated by organizational identification and professional identity, respectively. Besides, the association between servant leadership and employee resilience was sequentially mediated from organizational identification to professional identity, and from professional identity to organizational identification. This study provides the first evidence of the predictive effect of servant leadership on employee resilience through organizational identification and professional identity, highlighting the significance of social identity for building and maintaining employees’ resilience in coping with challenges posed by COVID-19.

Keywords: Servant leadership, Organizational identification, Professional identity, Employee resilience, Public organizations

Introduction

The worldwide spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a global crisis threatening individuals’ well-being, especially in the workplace. Though some countries have opted for strict policies such as lockdowns, prescribed quarantine, and self-isolation (Pagliaro et al., 2021), unprecedented challenges have been posed to the employees’ psychological health and resilience (Mao et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2021). The latest survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 130 countries has shown that the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has caused 93% of countries worldwide to interrupt and even stop crucial mental health services (WHO survey, 2020). A Chinese national survey has exhibited that nearly 35% of its citizens claimed increased mental stress due to this pandemic (Qiu et al., 2020). Therefore, building and maintaining strong resilience becomes a priority for employees’ well-being (Gardner, 2019; Mao et al., 2022) and organizations’ sustainable development (Jung & Yoon, 2015).

Moreover, public organizations’ core mission underlines nothing more than serving citizens (Houston, 2005), yet, the burnout of their employees that arose when responding to COVID-19 threatens their physical and mental health (Pagliaro et al., 2021) and affects administrative efficiency (Hao et al., 2015). Therefore, the psychological resilience of employees in public organizations deserves research attention as it helps serve citizens well (Danaeefard et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2019).

Since COVID-19 is inevitable for all individuals, teams, and organizations, building and maintaining resilience has become an essential strategy concerning their success, survival, and growth (Mao et al., 2020). Though resilience is applied to all levels of workplace analysis, its application in public organizational contexts is still insufficient (King et al., 2016). Furthermore, the study of public organizations’ employee resilience concerning their perceived servant leadership is also sparse. However, the importance of leadership - that focuses on leadership behavior and effectiveness, has been addressed in affecting subordinates’ psychology, attitude, and behavior (Anderson & Sun, 2015). Indeed, few studies on the association between resilience and servant leadership have been addressed yet have respective limitations. For instance, a theoretical article by Eliot (2020) provided an overview of specific theories and research contributing to the concept of resilience while also examining the behaviors related to servant leadership and how they influence the leader’s followers. Eliot concluded that leaders with a higher level of resilience could respond more positively to crises their organizations may encounter. In addition, servant leaders can have a similar positive impact on their followers’ resilience.

For example, a recent study by Wiroko (2021) found that perceived supervisor’s servant leadership and employees’ workplace resilience positively impact work engagement, and multiple linear regression analysis showed that servant leadership and resilience significantly influence bank employees’ work engagement with a total contribution of 26% explained variance. This means that servant leadership is essential in complementing the employees’ resilience in gaining work engagement. Wilkinson (2020) demonstrated a direct relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience, and servant leadership explained 11% of the variance in predicting employee resilience. Employee resilience has been found to mediate the link between servant leadership and turnover intention in high school institutions (Mustamil & Najam, 2020). Employee resilience also mediates the association between servant leadership and workplace bullying (Ahmad et al., 2021). Although these findings are still in the early stages of exploration, how employee resilience is developed and affects workplace outcomes, work teams, and general organizational behavior (King et al., 2016) needs further investigation. Therefore, we hope to uncover the underlying mechanism of the association between employees’ perceived servant leadership in public organizations and their resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Moreover, it is worth mentioning that when an individual is in a relatively larger social entity (i.e., social and physical organizational context), he or she can not only be driven to interact with people with similar goals, values, and beliefs but also to act as a member of the organization to redefine him or herself (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). That is, organizational identification and professional identity reflect that an individual’s identity is stemmed from a sense of belongingness to different groups of organizations (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) and professions (Hofman, 1977). Therefore, these sub-constructs were treated as two parallel concepts subordinated to social identity based on the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986).

Previous studies have found that servant leadership positively predicts organizational identification (Chughtai, 2016; Worley et al., 2020). Prior empirical research on the nurse population from 12 cities in China demonstrated that organizational identity positively influences organizational members’ resilience during COVID-19 (Lyu et al., 2020). Taken together, above-mentioned works suggest an underlying relationship between servant leadership and resilience through organizational identification.

However, direct support for the link between servant leadership and professional identity can be barely traced in literature, to the best of our knowledge, and insofar. Still, implicit and budding evidence suggests such a link. For instance, public organizations’ leaders significantly impact their employees’ career success (Volmer et al., 2016), and leadership in public organizations can bring about an employee’s job satisfaction (Adiguzel et al., 2020). As direct support for the link between professional identity and resilience is well documented (Boldrini et al., 2018), all these works seem to suggest an underlying relationship between servant leadership and resilience through professional identity.

To this end, our research, conducted under the COVID-19 scenario, aimed to examine the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience and test their underlying mechanisms by considering two parallel sub-constructs of social identity (i.e., organizational identification and professional identity) based on a social identity approach. This study sought to have two contributions: (1) Although the limited literature has examined the influence of servant leadership on employee resilience (i.e., Bouzari & Karatepe, 2017), the servant leadership-resilience study from the social identity perspective has not been thoroughly investigated in the literature. Therefore, this study provides a new perspective to explore the potential process through which servant leadership impacts employee resilience by empirically examining the mediating effect of social identity (i.e., organizational identification and professional identity) based on social identity theory. (2) Servant leaders working at public organizations, this group of people who serve their citizens by assisting in combating COVID-19 while also seeking self-protection in coping with such a prevalent pandemic, are more vulnerable to COVID-19. Therefore, their resilience, which has been neglected, calls for more research attention. To respond to this call, our study uses public organization employees as a sample to address this research gap. It helps understand how servant leaders can help their followers improve organizational identification, professional identity, and resilience.

Theory and hypotheses

Social identity approach

Social identity refers to an individual’s feeling that he or she is a group member and tends to divide himself or herself into different social categories from others (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). According to the social identity theory, individuals tend to define themselves through group membership (Tajfel, 1978). Therefore, when they are in a relatively large social entity (i.e., social and physical organizational context), they are more inclined to interact with people with similar values and redefine themselves according to their membership role within the organization (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Indeed, organizations seek to extend personal identification to organizational identification; hence it is believed that organizational identification is a specific form of social identity (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). In addition, the professional identity- another form of social identity that distinguishes people from other professionals (Adams et al., 2006)- reflects the sense of belonging or recognition of personal identity to their profession (Hofman, 1977). Hence one can see that organizational identification and professional identity reflect the sense of belonging in an individual’s identity toward organizational groups (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) and professions (Hofman, 1977). In this regard, we believe that organizational identification and professional identity are two parallel concepts subordinated to social identity based on the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986).

Servant leadership and employee resilience

Greenleaf (1977, p.14) mentioned servant leadership by introducing servant leaders into the organizational context: “The servant-leader is a servant first. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve first. Then the conscious choice brings himself to aspire to lead”. Later, van Dierendonck (2011) put forward that servant leadership is demonstrated by empowering and developing people and expressing humility, authenticity, interpersonal acceptance, etc. Compared to other leadership styles, such as transformational, authentic, and ethical leadership, servant leaders put the subordinates’ needs at top priority and in the first place (Greenleaf, 1977), and they emphasize serving others in organizations to improve the well-being of followers (der Kinderen et al., 2020). Thus, rather than organizational goals, servant leadership shows a natural tendency to serve marginalized groups and focuses more on followers (Sendjaya et al., 2008), as well as employee behaviors and attitudes, including potential training in areas such as job performance, self-motivation and employee creativity (Liden et al., 2014; Lumpkin & Achen, 2018; Yang et al., 2019).

Employee resilience refers to the ability to adapt to changes in the current environment (London, 1993); that is, to still moderately “bounce back” in the face of tremendous pressure (Bani-Melhem et al., 2021). Recent research has indicated that as a coping resource, employee resilience helps reduce the emotional exhaustion caused by negative emotions (Al-Hawari et al., 2019), and helps the organization resume normal operations after a crisis (Kim, 2020). Meanwhile, employee resilience- an individual’s ability to actively adapt to adversity- appears to be linked to one’s confidence in organizational adaptability, organizational traits, and the right decision-makers (Cope et al., 2016). Existing research has explored many factors affecting employee resilience, such as work adjustment (Davies et al., 2019) and leaders’ developing long-term relationships of mutual trust with their followers (Caniëls & Hatak, 2019). However, existing literature about the influential factors on employee resilience in public organizations has remained inconclusive, especially in a current crisis like COVID-19, when fear and insecurity brought unprecedented and prominent pressure to organizations and individuals. Accordingly, in-depth research for uncovering the underlying mechanism of the link between servant leadership and employee resilience needs further exploration (Cope et al., 2016).

Though explicit evidence of the servant leadership-employee resilience association is sparse, to our best knowledge, sparking supportive evidence can be traced in limited research records. For instance, servant leadership positively influences psychological capital, of which employee resilience is included as one dimension (Bouzari & Karatepe, 2017). A recent investigation revealed an underlying mechanism between servant leadership and psychological capital: person-group fit and person-supervisor fit work as independent mediators (Safavi & Bouzari, 2020).

Servant leaders can benefit followers by increasing their resilience to reduce work pressure, improve recovery from adversity, and increase work performance (Gillet et al., 2011). For instance, a study targeting 2,636 teachers from schools in south China confirms that servant leadership moderates the relationship between challenge stressors and emotional exhaustion (Wu et al., 2019). Servant leadership helps anxious employees maintain a stable working state (Hu et al., 2020) and prevent burnout (Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2020). Besides, servant leadership can positively influence followers’ service behaviors, making them more confident in their serviceability and engaging in more service behaviors (Wu et al., 2021). These findings are further backed up by prior work, which averred that an employee would be more resilient and optimistic in an environment that respects and admires servant leaders (Bouzari & Karatepe, 2017). Therefore, we assume that:

H1: Servant leadership is positively associated with employee resilience.

Servant leadership and employee resilience: organizational identification as a mediator

Organizational identification, embedded in social identity theory, refers to people’s understanding of themself as organization members and the members’ values and emotional significance (Tajfel, 1978). According to Self-Categorization Theory (Turner et al., 1987) which is embedded in Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979, 1986), individuals identify with their groups through social categorization and then promote in-group favoritism and out-group hostility. In other words, a part of an individual’s identity comes from their belongingness to various social groups, and their emotional response and cognitive evaluation are related to this sense of belongingness. It is worth noting that a person’s identification with the group as a member is regulated by different or higher levels of self, which means that an individual will transfer to a higher level as part of the relevant groups without losing themself in different social backgrounds. Therefore, social identity theory assumes that the individuals, as members of social units (collective groups, organizations, and cultural communities), think, feel and act in a particular environment, and the behavior of the individuals reflects these social units. As a specific form of social identity, organizational identification is defined as “one’s perception with or belongingness to an organization, where the individual defines himself or herself in terms of the organization(s) in which he or she is a member” (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Thus, when individuals define themselves according to the identity of the relevant collective or role, they are ready and willing to develop their own identity and act in their best interests (Ashforth et al., 2008). In other words, organizational identification defines the self in a target organization (Ashforth, 2016), which is how individuals adapt to express themselves using their membership in a particular organization (Boon et al., 2020).

The predictive role of servant leadership towards organizational identification has been thoroughly studied within extensive literature. For instance, an empirical study on a group of athletes has provided evidence that enhanced organizational identification (as one specific aspect of social identity) is influenced by servant leadership (Worley et al., 2020). Meanwhile, a study of 174 food company employees from Pakistan has verified that organizational identification partially mediates the influence of servant leadership on the voice and negative feedback-seeking behavior (Chughtai, 2016). In addition, a survey of 126 CEOs in the United States has demonstrated that organizational identification positively predicts servant leadership (Peterson et al., 2012). Servant leadership also positively influences employees’ commitment and behaviors to a large extent (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, 2018), enhancing employees’ sense of organizational support and identification (Otero-Neira et al., 2016).

Besides, a recent study on a group of 216 nurses from 12 cities in China has shown that organizational identity positively influences the psychological resilience of organization members during COVID-19 (Lyu et al., 2020). In turn, employees with higher stability also exhibit a higher level of organizational identity as they are more active when engaging in work (Gibson et al., 2020). Motivated by the theory of social identification (being the higher-level concept for organizational identification) that is found to involve a social-psychological process that supports team resilience (Morgan et al., 2015), the empirical evidence on the impact of organizational identification on resilience (Thompson & Korsgaard, 2019), and taken together with prior hypothesis H1, we, therefore, propose that:

H2: Organizational identification mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience.

Servant leadership and employee resilience: professional identity as a mediator

Professional identity refers to the values and beliefs held by the employees toward their professional work and jobs (Fagermoen, 1997), as well as a series of schematic thoughts about the ideal future self and how these thoughts are more broadly related to the individuals’ sense of professional career (Tomlinson & Jackson, 2019). Put another way, professional identity represents the employees’ identification with their jobs. For example, they think their professional role is essential, attractive, and compatible with other parts (Hofman, 1977). Therefore, as a form and a sub-construct of social identity for people to distinguish their professions from other professionals, professional identity is composed of factors such as self-image, social recognition, job satisfaction, social relations, attitudes toward change, professional competence, and expectations for the future of their professions (Adams et al., 2006).

Professional identity concerning servant leadership cannot be substantially traced in limited records. However, few pieces of implicit and indirect evidence may support such a relation. For instance, the study of leadership development program cohorts in the southeast U.S. revealed that servant leadership is positively and significantly correlated with faculty’s mentoring competencies (i.e., professional development); that is, servant leaders bring socio-emotion and career development to their followers (Sims et al., 2020). A study of 2,453 employees from 34 organizations in Finland has discerned that an enhanced concept of servant leadership is related to increased work engagement (Kaltiainen & Hakanen, 2020). Besides, a study of time-lagged data collected from Turkish hotel employees and their direct supervisors has further demonstrated that servant leadership indirectly impacts career satisfaction through work engagement (Kaya & Karatepe, 2020). Servant leaders significantly impact their employees’ career success (Volmer et al., 2016). Furthermore, recent work has found that job satisfaction positively predicts professional identity (Butakor et al., 2021); in other words, when employees feel a great sense of engagement or satisfaction at work, their understanding of work is further deepened, and their professional identity subsequently enhanced (Hofman, 1977). To this end, we assume that servant leadership may positively impact professional identity.

Moreover, the study of professional identity and its impact on employee resilience can be traced to prior work. For instance, a qualitative study using grounded theory has indicated that people’s resilience is rooted in professional identity (Winkel et al., 2018). The resources related to professional identity and available personal resources help affect resilience in a sample of teachers (Boldrini et al., 2018). Nonetheless, most prior studies on professional identity and resilience are conducted in public organizations such as universities (Zhang et al., 2016), while such studies in government organizations were neglected. A survey of civil servants in Beijing showed that civil servants had become an essential target for investigating resilience (Hao et al., 2015). Based on the above findings and reference reasoning, we, therefore, anticipate that:

H3: Professional identity mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience.

Servant leadership and employee resilience: the sequential mediation effects of organizational identification and professional identity

Prior assumptions (H2 and H3) have proposed that servant leadership helps promote employee resilience not only through the promotion of organizational identification but also through enhancing an employee’s professional identity. Question on what’s the relationship between these two mediators, answers can be found in some empirical works. For instance, a survey on a group of 252 employees in the USA Big 5 auditors has identified that professional identity positively predicts organizational identification (Bamber & Iyer, 2002), and subsequent study has supported that the higher level of one’s professional identity, the higher level their organizational identification (Salvatore et al., 2018).

However, paradoxical findings also support a reverse direction. For instance, a recent work conducted in seven nursing homes in Northeast England suggested that organizational identification positively impacts professional identity in a group of nurses (Thompson et al., 2018); the shared organizational identification can alleviate the adverse effects of professional identity differences (Mattarelli & Tagliaventi, 2010). Considering the bi-directional impact between organizational identification and professional identity and taking together H2 and H3, we, therefore, propose that:

H4: Servant leadership indirectly predicts employee resilience by the sequential mediation effects of organizational identification and professional identity. Specifically,

H4a: Servant leadership - organizational identification - professional identity - employee resilience

H4b: Servant leadership - professional identity - organizational identification - employee resilience

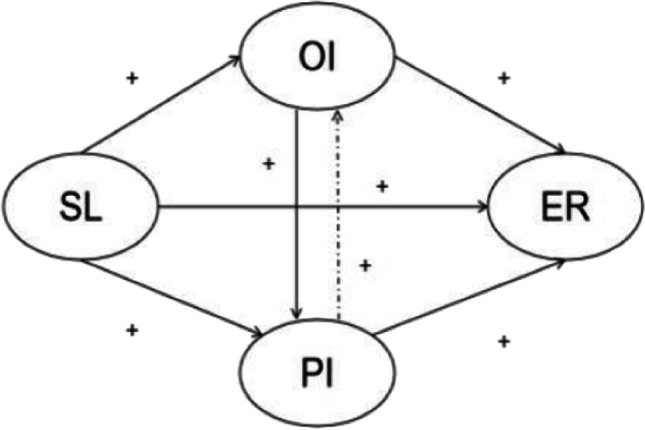

To the best of our knowledge, the exploration of servant leadership with its effect on employee resilience has not yet been dated from the lens of a social identity perspective. Nevertheless, the investigation into the population of employees of public organizations within the context of COVID-19 has mainly been neglected. To fill these gaps, we aimed to test the above hypotheses (as indicated in Fig. 1) via a group of Chinese employees from public organizations that emphasized the collective value in such a turbulent context of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model. Notes. SL - servant leadership; OI - organizational identification; PI - professional identity; ER - employee resilience

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data were collected by questionnaire survey among employees from different public organizations (such as government, public schools, hospitals, etc.) in southwest China. This study was approved by the local ethical committee of the first author’s university and conducted according to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Before filling out the questionnaire, participants were notified about the purpose of the research and given online informed consent. They were told that the survey was anonymous and that their participation was voluntary, as they had the right to withdraw participation or opt out at any time during the study. We approached 1000 employees, of which 720 answered the questionnaire (the response rate was 72%). After excluding the invalid responses that took too short to fill in and failed attention check, we obtained a final sample of 703 employees (the completion rate was 70.30%). Their gender, age, length of serving years, academic qualifications, and job position are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Social demographic features of participants (N = 703)

| Variables | N | Percentages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 289 | 41.11% |

| Female | 414 | 58.89% | |

| Age | Less than 20 | 1 | 0.14% |

| 21–30 | 322 | 45.80% | |

| 31–40 | 328 | 46.66% | |

| 41–50 | 42 | 5.97% | |

| Above 50 | 10 | 1.42% | |

| Length of serving years | Less than 6 Months | 20 | 2.85% |

| 6 Months to 1 Year | 17 | 2.42% | |

| 1 to 2 Years | 60 | 8.53% | |

| 2 to 3 Years | 73 | 10.38% | |

| 3 to 5 Years | 204 | 29.02% | |

| Over 5 Years | 329 | 46.80% | |

| Academic qualifications | High School | 3 | 0.43% |

| Junior College | 23 | 3.27% | |

| Bachelor | 513 | 72.97% | |

| Master | 162 | 23.04% | |

| PhD | 2 | 0.28% | |

| Job position | Higher-Level Employees | 21 | 2.98% |

| Middle-Level Employees | 225 | 32.01% | |

| Common Employees | 457 | 65.01% |

As for the procedure, firstly, the questionnaire was translated by the back-translation method (Brislin, 1986) The original English items were first translated into Chinese and then, using an independent translator, back into English. After this, the original and the back-translated versions were compared to create a Chinese version. Then, questionnaire items were prepared online and administered via the URL link and QR (quick response) code to potential employees in public organizations for a pilot test. Based on the piloting results, the ambiguous items were modified to form the final questionnaire. Finally, the online questionnaire was formally administered by sending it to the potential employees. Data were collected from January 15th, 2021, to January 31st, 2021.

Measures

Responses to each measure were registered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Servant leadership

To measure servant leadership in public organizations, we employed a 6-item questionnaire adapted from Sendjaya et al. (2017) (e.g., “My immediate leaders use power to serve others, not for their ambitions”). This scale has been applied to the Chinese cultural sample (Wu et al., 2019). The Cronbach’s α regarding the present sample was 0.919.

Organizational identification

The scale of organizational identification developed by Mael and Ashforth (1992), adopted in our study, was designed to measure employees’ identification with their organizations (Barattucci et al., 2020). The sample item is “When someone criticizes my working organization, it feels like a personal insult”. Two items with factor loadings lower than 0.40 were excluded (Hair et al., 1995), and a 4-item organization identification scale was included for further analysis in our study, with adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.796).

Professional identity

We adopted a 6-item modified professional identity scale developed by Adams et al. (2006), which originated from Brown et al. (1986) for measuring group identity. The sample item is “I feel like I am a member of this profession”, and the scale has been proved valid and reliable (Worthington et al., 2013). The Cronbach’s α of the present sample was excellent (0.915).

Employee resilience

We utilized a 5-item scale compiled by London (1993) to assess the resilience of employees in the public organization (e.g., “I can build and maintain friendship with people from different departments in my organization”). The Cronbach’s α of the present sample was 0.879.

Data analytical strategy

We conducted the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett test (significance p-value) for each of our study variables within SPSS (25.0). The KMO values greater than 0.70 with the significance of the Bartlett sphere test (p < 0.001) (Kaiser & Rice, 1974; Vignola & Tucci, 2014) indicated that they were suitable for further confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Next, we performed CFA in AMOS (24.0) to test our measurement model. Specifically, a set of indices were considered for the model fit: the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; < 0.05 indicating good fit, 0.05-0.08 indicating acceptable fit) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; ≤ 0.08 indicating acceptable fit) (Kline, 2015), the chi-square/degree of freedom ratio (1 < χ2/df < 3), the comparative fit index (CFI) above 0.95 (Bentler, 1990), goodness-of-fit index (GFI) greater than 0.90, incremental fit index (IFI; > 0.90), non-normed fit index (NNFI; > 0.90), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; > 0.90) (Hsu et al., 2012). Finally, we tested the hypothesized mediation model via the bootstrapping method within AMOS (24.0).

Results

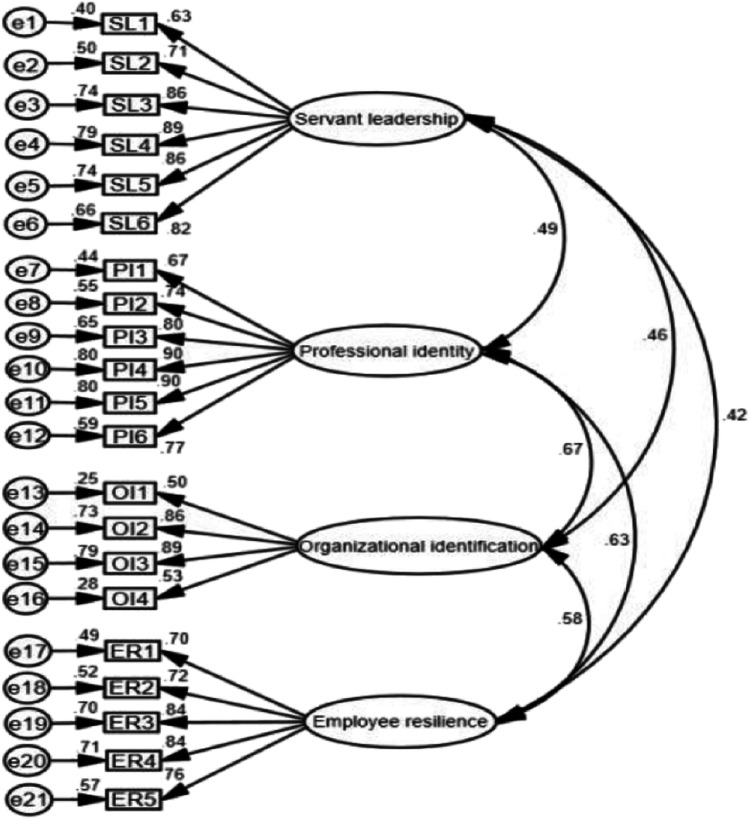

Descriptive statistics, reliability, validity, and correlation

The descriptive statistics, reliability, validity, and correlation of all study variables are presented in Table 2. The results showed that all study variables (servant leadership, organizational identification, professional identity, and employee resilience) were positively (r > 0.38) and significantly (p < 0.01) intercorrelated. Besides, the values of the composite reliability (CR > 0.60; Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) and the average variance extraction (AVE > 0.50; Fornell & Larcker, 1981) indicated good construct reliability and convergence validity. Table 2 presents the square root of each scale’s AVE, indicating good discriminant validity among constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability, validity and correlational indices of variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Bartlett’s Test | KMO | AVE | C.R | SL | OI | PI | ER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | SE | Statistics | |||||||||

| SL | 3.422 | 0.033 | 0.888 | 0.000 | 0.877 | 0.644 | 0.915 | 0.802 | |||

| OI | 3.983 | 0.031 | 0.806 | 0.000 | 0.718 | 0.517 | 0.800 | 0.413** | 0.719 | ||

| PI | 3.802 | 0.032 | 0.841 | 0.000 | 0.894 | 0.636 | 0.912 | 0.456** | 0.642** | 0.797 | |

| ER | 4.115 | 0.024 | 0.650 | 0.000 | 0.869 | 0.610 | 0.886 | 0.377** | 0.566** | 0.611** | 0.781 |

**, p < .01. Discriminant validity of variables are in parentheses along the diagonal

Measurement model testing and common method variance

The measurement model consisted of four latent variables (servant leadership, organizational identification, professional identity, and employee resilience) with the corresponding 21 observed indicators. We performed CFA in AMOS (24.0) to test our measurement model via a structural equation modeling approach with maximum likelihood estimation. Results (see Fig. 2) showed a good fit to the data (χ2 = 484.859; df = 175; χ2/df = 2.771; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.046; CFI = 0.970; TLI = 0.964). Then, we added the common method factor on this basis, and the results showed that the new measurement model had not been significantly optimized after adding the common method factor (χ2 = 593.472; df = 162; χ2/df = 3.663; RMSEA = 0.062; SRMR = 0.036; CFI = 0.958; TLI = 0.945; IFI = 0.958) (the change of RMSEA and SRMR was respectively no more than 0.05, and the change of CFI and TLI was respectively no more than 0.1), indicating that there is no obvious common method variance in the measurement model (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Fig. 2.

Test of the measurement model

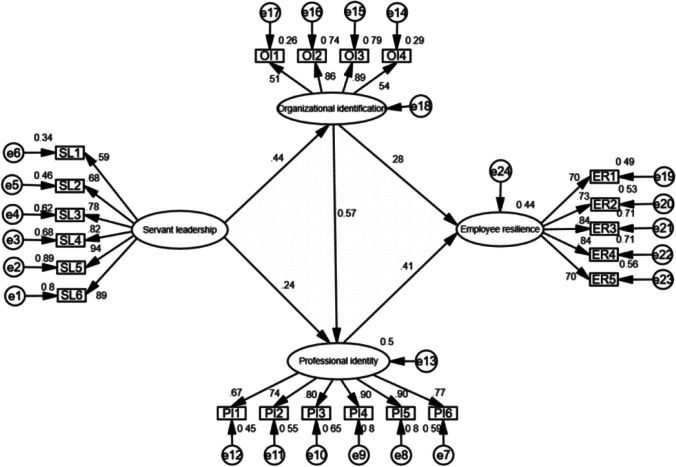

Test of hypotheses via structural equation modeling

In our hypothesized model, SL was the predictive variable, ER was the dependent variable, and OI and PI were the mediating variables (Model 1: OI and PI as the sequential mediator; Model 2: PI and OI as the sequential mediator). The results of a set of fitting indices for the structural Model 1 shown in Table 3 was acceptable (χ2/df = 2.722; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.965; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.043), and the fitting indices of Model 2 were also acceptable (χ2/df = 2.689; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.965; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.042).

Table 3.

Fitting indices for the hypothesized model and adjusted model

| χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized model 1 | 976.156 | 183 | 5.334 | < 0.001 | 0.922 | 0.911 | 0.079 | 0.054 |

| Adjusted model 1 | 468.189 | 172 | 2.722 | < 0.001 | 0.971 | 0.965 | 0.050 | 0.043 |

| Hypothesized model 2 | 976.156 | 183 | 5.334 | < 0.001 | 0.922 | 0.911 | 0.079 | 0.054 |

| Adjusted model 2 | 470.578 | 175 | 2.689 | < 0.001 | 0.971 | 0.965 | 0.049 | 0.042 |

To test our hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4a) in Model 1, we present the standardized path coefficient of the structural model as displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 3. As indicated in Fig. 3, the standardized path coefficient between SL and ER was insignificant (p > 0.05). Therefore, H1 was rejected. Subsequently, the bootstrapping method via AMOS (24.0) was used to test the significance of the whole mediational model (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Specifically, the Bootstrap estimation procedure (5000 bootstrap samples) was applied to examine the indirect effects (see Table 5), if zero was not included within the 95% confidence intervals for both OI and PI, then significant indirect effect was found. As indicated in Table 5, the indirect effect of SL on ER via OI was significant, thus supporting H2; the indirect effect of SL on ER via PI was also significant, supporting H3. Besides, the indirect effect of SL on ER through the sequential mediation of OI and PI (H4a: SL—OI—PI—ER) was significant.

Table 4.

Hypothesis test

| Hypothesis | Path | Effect value | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Model 1 | |||||

| H1 | SL → ER | 0.040 | -0.025 | 0.073 | 0.361 |

| H2 | SL → OI → ER | ||||

| SL → OI | 0.439 | 0.146 | 0.267 | 0.000 | |

| OI → ER | 0.284 | 0.217 | 0.494 | 0.000 | |

| H3 | SL → PI → ER | ||||

| SL → PI | 0.240 | 0.127 | 0.267 | 0.000 | |

| PI → ER | 0.412 | 0.207 | 0.377 | 0.000 | |

| H4a | SL → OI → PI → ER | ||||

| OI → PI | 0.571 | 0.806 | 1.236 | 0.000 | |

| Model 2 | |||||

| H1 | SL → ER | 0.085 | -0.006 | 0.176 | 0.060 |

| H2 | SL → OI → ER | ||||

| SL → OI | 0.167 | 0.090 | 0.246 | 0.000 | |

| OI → ER | 0.309 | 0.195 | 0.429 | 0.000 | |

| H3 | SL → PI → ER | ||||

| SL → PI | 0.485 | 0.403 | 0.554 | 0.000 | |

| PI → ER | 0.385 | 0.272 | 0.482 | 0.000 | |

| H4b | SL → PI → OI → ER | ||||

| PI → OI | 0.572 | 0.492 | 0.651 | 0.000 | |

Fig. 3.

Test of the hypothesized model 1

Table 5.

Standardized indirect effects with 95% confidence intervals

| Model pathways | SE | Estimated | 95CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Model 1 | ||||

| SL → OI → ER | 0.029 | 0.125 | 0.074 | 0.190 |

| SL → PI → ER | 0.022 | 0.099 | 0.061 | 0.150 |

| SL → OI → PI → ER | 0.019 | 0.103 | 0.071 | 0.145 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| SL → PI → ER | 0.020 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.057 |

| SL → OI → ER | 0.010 | 0.115 | 0.080 | 0.158 |

| SL → PI → OI → ER | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

Similar strategies were also applied to test our hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4b) in Model 2. As indicated in Table 4 and Fig. 4, the standardized path coefficient between SL and ER was insignificant (p > 0.05), rejecting H1. Following, the bootstrapping method via AMOS (24.0) was applied to test the significance of the whole mediational model (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The Bootstrap estimation procedure (5000 bootstrap samples) was applied to examine the indirect effects (see Table 5). As zero was not included within the 95% confidence intervals for both PI and OI, significant indirect effects were obtained between SL and ER through both OI and PI. Therefore, H2 and H3 were supported. Moreover, the sequential mediation of PI and OI (H4b: SL—PI—OI—ER) was also significant.

Fig. 4.

Test of the hypothesized model 2

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience in public organizations by testing a model in which two types of social identity (organizational identification and professional identity) were considered under the COVID-19 challenging context. We targeted the public organizations’ population to understand better the main effect of servant leadership provided by leaders who serve in public organizations on their followers’ resilience. Specifically, within the context of COVID-19, which has posed more severe challenges to employees in public organizations (Pagliaro et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021), they need to protect themselves while serving other citizens, therefore building and maintaining strong resilience is of great significance in coping with COVID-19. The significant and full mediation effect provided by organizational identification and professional identity emphasized the importance of social identity in the contribution of the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience, especially in the COVID-19 context. At the same time, employees’ resilience was reflected by a set of positive coping behaviors (with COVID-19), demonstrating personal identification with organizations (collective social groups) through the lens of social identity perspective in the collectivistic culture in China (Lu et al., 2021).

Theoretical implications

Our research makes several contributions. First, by investigating how SL affects ER, we extend our understanding of the underlying mechanism between SL and ER via a group of employees from public organizations, which has been largely overlooked. The findings of this study add to the leadership and employee resilience literature through the lens of social identity. Our results rejected hypothesis H1, failing to support that SL can directly predict ER (Bouzari & Karatepe, 2017; Safavi & Bouzari, 2020). This may be because those public organizations’ characteristics of risk aversion and red tape (Nicholson-Crotty et al., 2016; Turaga & Bozeman, 2005) may not be able to make their employees perceive servant leadership intuitively, as it is a process that requires transformation.

Meanwhile, in managing the COVID-19 crisis, an important function of leaders is to awaken the cognitive framework of employees (i.e., organizational identification and professional identity) (James et al., 2011), which, in turn, affects the resilience of employees. Therefore, one possible interpretation could be that SL helps assist employees in obtaining organizational support, boost OI (Otero-Neira et al., 2016), and bring positive employee performance (Gibson et al., 2020). In addition, as some studies have shown that PI positively predicts teachers’ resilience (Boldrini et al., 2018), and PI may bring about positive work-related behaviors (Zhang et al., 2016), SL is therefore predictive for ER via OI and PI. In this regard, SL relates to ER only in a specific task within a given context, since it empowers positive responses (encouraging and promoting others to take responsibility and deal with difficulties in their own way), encourages helping subordinates grow and succeed (Liden et al., 2008), and decreases the employees’ psychological burden.

Second, we contribute to servant leadership literature by uncovering the underlying mechanisms through which SL may promote ER. Prior research has concluded that person-group fit and person-supervisor fit (as two independent mediators) help explain the relationship between SL and ER (Safavi & Bouzari, 2020). Yet, the social identity perspective (i.e., OI and PI) of the relationship between SL and ER has been ignored. On the one hand, our findings were in line with previous studies on the positive relationship between SL and OI (Chughtai, 2016; Worley et al., 2020), and between OI and ER (Augusto et al., 2019; Lyu et al., 2020; Morgan et al., 2015; Thompson & Korsgaard, 2019). Moreover, as hypothesized in H2, the positive effect of SL on ER was fully mediated by OI, which represents a novel contribution. Such a finding has provided evidence that SL played within a public organization helps facilitate the resilient behavior of employees and their team members (Lapointe & Vandenberghe, 2018), assists the employees gaining a sense of organizational support and boost OI (Otero-Neira et al., 2016), thereby improving OI and bring about the positive performance (Gibson et al., 2020).

On the other hand, this study also contributes to the professional identity literature by identifying PI as a crucial mediating mechanism that helps enrich the effect of SL on ER. With regard to our hypothesis H3, our finding validated the direct positive relationship between SL and PI, which has not been found in prior limited research records. In brief, SL effectively predicts employees’ adaptive performance by encouraging their work engagement (Kaltiainen & Hakanen, 2020) and increasing their career satisfaction (Kaya & Karatepe, 2020), thereby promoting their professional identity. In addition, our study has confirmed a connection between PI and ER, extending prior research (Winkel et al., 2018). In this regard, the impact of SL on ER through the mediation of PI, supporting previous findings from a group of teachers (Boldrini et al., 2018), confirms that PI may bring about positive work-related behaviors (Zhang et al., 2016), positive spiritual well-being, and job satisfaction (Zhang et al., 2018). Thus, our findings extend the application of social identity theory by establishing the theoretical connection between SL and ER from the two above-mentioned identities (OI and PI).

Finally, we highlight our significant and novel finding in that we uncover the underlying mechanism of the link between SL and ER, by jointly considering OI and PI from a social identity perspective. This result has added to the leadership and employee resilience literature, and provided evidence for the role of OI and PI as the joint mechanism between SL and ER. As the main works of servant leaders in public organizations are (1) providing help and support to their followers, (2) putting the subordinates’ needs at top priority and in the first place (Greenleaf, 1977), and (3) emphasizing serving others including followers (der Kinderen et al., 2020), all these help increase employees’ belongingness to and identification with their organization and profession, which in turn impact employee resilience (Boldrini et al., 2018). Results of H4a from the present dataset confirm that a higher level of organizational identification is associated with a higher level of professional identity (Mattarelli & Tagliaventi, 2010; Thompson et al., 2018). At the same time, results of H4b confirm that a higher level of professional identity is linked with a higher level of organizational identification (Bamber & Iyer, 2002; Salvatore et al., 2018). Therefore, this study provides a nuanced and comprehensive perspective via social identity (i.e., OI and PI) to understand the SL-ER relationship. In addition, our work, by focusing on employees in public organizations in the current ongoing COVID-19 context that their resilience deserves more attention (Danaeefard et al., 2022), provides new insight on that promoting people’s well-being should not only for citizens but also for those who serve these citizens. In this sense, our study proposes to increase the positive psychological capital (i.e., resilience) for all.

Practical implications

First, leaders of public organizations should realize that they are service providers rather than political managers enforcing authorities. In addition to satisfying the material needs of their subordinate employees, they need to maintain spiritual attention, enhancing their followers’ sense of care for and belongingness to the public organization. Thus, they should be encouraged to create a good environment and atmosphere to narrow the physical and psychological distance to increase the support and trust of the employees. Psychologically, frequent interactions via face-to-face communication during lunchtime, at an off-hour, or during tea break help leaders listen to and better understand their subordinating employees’ emotional, material, and organizational needs, making them feel at home within the organization facilitating corporation and professional identification. Physically and environmentally, leaders are advised to create a safe, comfortable, bright, and spacious workplace (i.e., spacious working space, cozy office arrangement, planted natural greenness with better window view, etc.). All these help facilitate organizational identification and professional identity (Bonaiuto et al., 2016), which builds and strengthens employee resilience.

Second, as public organizations face severe challenges serving their citizens, especially during the COVID-19 period, leaders serving in public organizations should be concerned and put effort into coordinating the relationship between their organizations and employees. For instance, leaders should play an exemplary role in the construction of organizational culture, in doing so, to enable employees to understand the profound connotation of organizational culture further, strengthen their sense of responsibility and belongingness, and enhance their organizational identification. Meanwhile, leaders should also help employees determine a clear professional plan and organize multi-level training to acquire relevant knowledge and skills to improve their career satisfaction and professional work (Butakor et al., 2021), thereby enhancing employees’ professional identity. In short, through massive strategies, leaders can help improve their employees’ organizational identification and professional identity to increase employee resilience in responding to challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitation and future research

There are some limits that warrant notices. First, our data is cross-sectional, which hinders the causal inference. Therefore, ongoing work using a time-lagged longitudinal and strict experimental design will lead us better understand the causality between leadership and employee resilience. Secondly, participants were employees from public organizations, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings to other populations or cultures. Thirdly, as only organizational identification and professional identity have been studied, future work may benefit by considering different identities such as personal identity (Winkel et al., 2018), ethnic identity, and so on in such a relationship by employing more sound methods such as qualitative comparative analysis and time-series analysis with a cross-lagged model. Future work may also profit from exploring other factors like the perceived organizational support (Al-Omar et al., 2019) that can contribute to employee resilience to depict a more global and comprehensive picture of employees’ resilience in public organizations.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the literature in several aspects. It sheds light on critical sources of employee resilience with leadership as a crucial driver built on the social identity theory. In particular, the validated conceptual model demonstrates that the underlying mechanisms between SL and ER are mediated by OI and PI, respectively, and sequentially. Therefore, this study is essential for servant leaders of public organizations to cultivate ER by improving/strengthening their employees’ identification with both organizations and professions, especially during COVID-19.

Funding

This work was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 20BZZ079), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant No. 72271205), Mental Health Education Research Center of Sichuan Province (Grant No. XLJKJY2002B).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study is approved by the local ethical committee of the first author’s university and conducted according to the ethical requirements established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Before filling out the questionnaire, participants were notified about the purpose of the research, given informed online written consent, and were told that the survey was anonymous. Their participation was voluntary as they had the right to withdraw participation or opt-out at any time during the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest concerning this research, authorship, and publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams K, Hean S, Sturgis P, Clark JM. Investigating the factors influencing the professional identity of first-year health and social care students. Learning in Health Social Care. 2006;5(2):55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-6861.2006.00119.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adiguzel Z, Ozcinar MF, Karadal H. Does servant leadership moderate the link between strategic human resource management on rule breaking and job satisfaction? European Research on Management and Business Economics. 2020;26(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.iedeen.2020.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Islam T, Sohal AS, Cox JW, Kaleem A. Managing bullying in the workplace: A model of servant leadership, employee resilience, and proactive personality. Personnel Review. 2021;50(7):1613–1631. doi: 10.1108/PR-06-2020-0470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hawari MA, Bani-Melhem S, Quratulain S. Do frontline employees cope effectively with abusive supervision and customer incivility? Testing the effect of employee resilience. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2019;35(5):223–240. doi: 10.1007/s10869-019-09621-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omar HA, Arafah AM, Barakat JM, Almutairi RD, Khurshid F, Alsultan MS. The impact of perceived organizational support and resilience on pharmacists’ engagement in their stressful and competitive workplaces in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2019;27(7):1044–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MH, Sun PYT. Reviewing leadership styles: Overlaps and the need for a new “full-range” theory. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2015;19(1):76–96. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE. Distinguished scholar invited essay: Exploring identity and identification in organizations: Time for some course corrections. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2016;23(4):361–373. doi: 10.1177/1548051816667897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S., & Corley, K. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management,34(4), 325–374. 10.1177/0149206308316059

- Ashforth BE, Mael FA. Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review. 1989;14(1):20–39. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1989.4278999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto M, Godinho P, Torres P. Building customers' resilience to negative information in the airline industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2019;50(1):235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structure equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,16(1), 74–94. 10.1007/BF02723327

- Bamber EM, Iyer VM. Big 5 auditors' professional and organizational identification: Consistency or conflict? Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory. 2002;21(2):21–38. doi: 10.2308/aud.2002.21.2.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Melhem, S., Quratulain, S., & Al-Hawari, M. A. (2021). Does employee resilience exacerbate the effects of abusive supervision? A study of frontline employees’ self-esteem, turnover intention, and innovative behaviors. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management,30(5), 1–19. 10.1080/19368623.2021.1860850

- Barattucci, M., Teresi, M., Pietroni, D., Iacobucci, S., Lo Presti, A., & Pagliaro, S. (2020). Ethical climate(s), distributed leadership, and work outcomes: The mediating role of organizational identification. Frontiers in Psychology,11(1):11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.564112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin,107(2), 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bonaiuto M, Mao Y, Roberts S, Psalti A, Ariccio S, Cancellieri UG, Csikszentmihalyi M. Optimal experience and personal growth: Flow and the consolidation of place identity. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7(67):1654. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini E, Sappa V, Aprea C. Which difficulties and resources do vocational teachers perceive? An exploratory study setting the stage for investigating teachers’ resilience in Switzerland. Teachers and Teaching. 2018;25(21):1–17. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1520086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boon J, Wynen J, Kleizen B. What happens when the going gets tough? Linking change scepticism, organizational identification, and turnover intentions. Public Management Review. 2020;23(4):1–25. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1722208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzari M, Karatepe O. Test of a mediation model of psychological capital among hotel salespeople. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2017;29(8):2178–2197. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2016-0022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Sage.

- Brown, R., Condor, S., Mathews, A., Wade, G., & Williams, J. A. (1986). Explaining intergroup differentiation in an industrial organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology,59(4), 273–278. 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1986.tb00230.x

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

- Butakor PK, Guo Q, Adebanji AO. Using structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between Ghanaian teachers’ emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, professional identity, and work engagement. Psychology in the Schools. 2021;58(2):534–552. doi: 10.1002/pits.22462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caniëls, M. C. J., & Hatak, I. (2019). Employee resilience: Considering both the social side and the economic side of leader-follower exchanges in conjunction with the dark side of followers’ personality. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,33(5), 1-32. 10.1080/09585192.2019.1695648

- Chughtai AA. Servant leadership and follower outcomes: Mediating effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. Journal of Psychology. 2016;150(7):866–880. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1170657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope V, Jones B, Hendricks J. Why nurses chose to remain in the workforce: Portraits of resilience. Collegian. 2016;23(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaeefard, H., Sedaghat, A., Kazemi, S. H., & Elahi, A. K. (2022). Investment areas to enhance public employee resilience during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Evidence from Iran. Public Organization Review, 22(3), 837–855. 10.1007/s11115-022-00617-w

- Davies SE, Stoermer S, Froese FJ. When the going gets tough: The influence of expatriate resilience and perceived organizational inclusion climate on work adjustment and turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2019;30(2):1393–1417. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2018.1528558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- der Kinderen S, Valk A, Khapova SN, Tims M. Facilitating eudaimonic well-being in mental health care organizations: The role of servant leadership and workplace civility climate. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(4):1173. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot JL. Resilient leadership: The impact of a servant leader on the resilience of their followers. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2020;22(4):404–418. doi: 10.1177/1523422320945237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fagermoen MS. Professional identity: Values embedded in meaningful nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(3):434–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,24(4), 337–346. 10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gardner DG. The importance of being resilient: Psychological well-being, job autonomy, and self-esteem of organization managers. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;155:109731. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CB, Dunlop PD, Raghav S. Navigating identities in global work: Antecedents and consequences of intrapersonal identity conflict. Human Relations. 2020;74(1):001872671989531. doi: 10.1177/0018726719895314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet J, Cartwright E, van Vugt M. Selfish or servant leadership? Evolutionary predictions on leadership personalities in coordination games. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51(3):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Paulist Press.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (1995). Multivariate data analysis: With readings. Prentice Hall.

- Hao, S., Hong, W., Xu, H., Zhou, L., & Xie, Z. (2015). Relationship between resilience, stress and burnout among civil servants in Beijing, China: Mediating and moderating effect analysis. Personality and Individual Differences,83(10), 65–71. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.048

- Hofman JE. Identity and intergroup perception in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1977;1(3):79–102. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(77)90021-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houston DJ. "Walking the walk" of public service motivation: Public employees and charitable gifts of time, blood, and money. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2005;16(1):67–86. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu IY, Su TS, Kao CS, Shu YL, Lin PR, Tseng JM. Analysis of business safety performance by structural equation models. Safety Science. 2012;50(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2011.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, He W, Zhou K. The mind, the heart, and the leader in times of crisis: How and when COVID-19-triggered mortality salience relates to state anxiety, job engagement, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105(11):1218–1233. doi: 10.1037/apl0000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James EH, Wooten LP, Dushek K. Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Academy of Management Annals. 2011;5(1):455–493. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2011.589594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HS, Yoon HH. The impact of employees' positive psychological capital on job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2015;27(6):1135–1156. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-01-2014-0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H., & Rice, J. (1974). Little jiffy, mark IV. Educational and Psychological Measurement,34(1), 111–117. 10.1177/001316447403400115

- Kaltiainen J, Hakanen J. Fostering task and adaptive performance through employee well-being: The role of servant leadership. Brq-Business Research Quarterly. 2020;25(1):28–43. doi: 10.1177/2340944420981599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya B, Karatepe OM. Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2020;32(6):2075–2095. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-05-2019-0438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King DD, Newman A, Luthans F. Not if, but when we need resilience in the workplace. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2016;37(5):782–786. doi: 10.1002/job.2063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Organizational resilience and employee work-role performance after a crisis situation: Exploring the effects of organizational resilience on internal crisis communication. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2020;32(1–2):47–75. doi: 10.1080/1062726x.2020.1765368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford.

- Lapointe E, Vandenberghe C. Examination of the relationships between servant leadership, organizational commitment, and voice and antisocial behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;148(1):99–115. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-3002-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Liao C, Meuser JD. Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2014;57(5):1434–1452. doi: 10.5465/amj.2013.0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Zhao H, Henderson D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly. 2008;19(2):161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London M. Relationships between career motivation, empowerment and support for career development. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1993;66(1):55–69. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00516.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JG, Jin P, English AS. Collectivism predicts mask use during COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118:e2021793118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021793118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin A, Achen RM. Explicating the synergies of self-determination theory, ethical leadership, servant leadership, and emotional intelligence. Journal of Leadership Studies. 2018;12(1):6–20. doi: 10.1002/jls.21554. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu H, Yao M, Zhang DY, Liu XY. The relationship among organizational identity, psychological resilience and work engagement of the first-line nurses in the prevention and control of COVID-19 based on structural equation model. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2020;13:2379–2386. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.S254928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mael F, Ashforth BE. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1992;13(2):103–123. doi: 10.1002/job.4030130202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y., Kang, X., Lai, Y., Yu, J., Deng, X., Zhai, Y., Kong, F., Ma, J., & Bonaiuto, F. (2022). Authentic leadership and employee resilience during COVID-19 pandemic: The role of flow, organizational identification, and trust. Current Psychology. 10.1007/s12144-022-04148-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y., Yang, R., Bonaiuto, M., Ma, J. H., & Harmat, L. (2020). Can flow alleviate anxiety? The roles of academic self-efficacy and self-esteem in building psychological sustainability and resilience. Sustainability,12(7):2987. 10.3390/su12072987

- Mattarelli E, Tagliaventi MR. Work-related identities, virtual work acceptance and the development of glocalized work practices in globally distributed teams. Industry and Innovation. 2010;17(4):415–443. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2010.496247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. B. C., Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2015). Understanding team resilience in the world’s best athletes: A case study of a rugby union World Cup winning team. Psychology of Sport and Exercise,16(1), 91–100. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.007

- Mustamil N, Najam U. The impact of servant leadership on follower turnover intentions: Mediating role of resilience. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting. 2020;13(2):125–146. doi: 10.22452/ajba.vol13no2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson-Crotty S, Nicholson-Crotty J, Fernandez S. Performance and management in the public sector: Testing a model of relative risk aversion. Public Administration Review. 2016;77(4):603–614. doi: 10.1111/puar.12619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Neira C, Varela-Neira C, Bande B. Supervisory servant leadership and employee's work role performance: A multilevel mediation model. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2016;37(7):860–881. doi: 10.1108/lodj-11-2014-0230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliaro S, Sacchi S, Pacilli MG, Brambilla M, Lionetti F, Bettache K, et al. Trust predicts COVID-19 prescribed and discretionary behavioral intentions in 23 countries. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(3):e0248334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SJ, Galvin BM, Lange D. CEO servant leadership: Exploring executive characteristics and firm performance. Personnel Psychology. 2012;65(3):565–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01253.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(2):e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi HP, Bouzari M. How can leaders enhance employees' psychological capital? Mediation effect of person-group and person-supervisor fit. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2020;33:100626. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore D, Numerato D, Fattore G. Physicians' professional autonomy and their organizational identification with their hospital. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18:775. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3582-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendjaya S, Eva N, Butar IB, Robin M, Castles S. Slbs-6: Validation of a short form of the servant leadership behavior scale. Journal of Business Ethics. 2017;156(4):941–956. doi: 10.1007/s10551-017-3594-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sendjaya, S., Sarros, J., & Santora, J. (2008). Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations. Journal of Management Studies,45(2), 402–424. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00761.x

- Shrout P, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims C, Carter A, Moore De Peralta A. Do servant, transformational, transactional, and passive avoidant leadership styles influence mentoring competencies for faculty? A study of a gender equity leadership development program. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2020;32(1):55–75. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

- Thompson BS, Korsgaard MA. Relational identification and forgiveness: Facilitating relationship resilience. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2019;34(2):153–167. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-9533-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Cook G, Duschinsky R. "I'm not sure I'm a nurse": A hermeneutic phenomenological study of nursing home nurses' work identity. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018;27(5–6):1049–1062. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Jackson D. Professional identity formation in contemporary higher education students. Studies in Higher Education. 2019;46(2):1–16. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turaga RMR, Bozeman B. Red tape and public managers’ decision making. American Review of Public Administration. 2005;35(4):363–379. doi: 10.1177/0275074005278503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Contemporary Sociology. 1987;94(6):645. doi: 10.2307/2073157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Upadyaya K, Salmela-Aro K. Social demands and resources predict job burnout and engagement profiles among Finnish employees. Anxiety Stress and Coping. 2020;33(3):403–415. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2020.1746285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dierendonck D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management. 2011;37(4):1228–1261. doi: 10.1177/0149206310380462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vignola RCB, Tucci AM. Adaptation and validation of the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) to Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;155(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmer J, Koch IK, Goritz AS. The bright and dark sides of leaders' dark triad traits: Effects on subordinates' career success and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;101:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO survey. (2020). COVID-19 disrupting mental health services in most countries. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/zh/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey. Accessed 11 Mar 2021

- Wilkinson, A. D. (2020). Investigating the relationship between servant leadership and employee resilience. Dissertation/Doctoral Thesis, Indiana Wesleyan University, Indiana

- Winkel, A. F., Honart, A. W., Robinson, A., Jones, A. A., & Squires, A. (2018). Thriving in scrubs: A qualitative study of resident resilience. Reproductive Health,15(1):53. 10.1186/s12978-018-0489-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wiroko, E. P. (2021). The role of servant leadership and resilience in predicting work engagement. Journal of Resilient Economies (ISSN: 2653–1917), 1(1). 10.25120/jre.1.1.2021.3821

- Worley JT, Harenberg S, Vosloo J. The relationship between peer servant leadership, social identity, and team cohesion in intercollegiate athletics. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2020;49(1):101712. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington M, Salamonson Y, Weaver R, Cleary M. Predictive validity of the macleod clark professional identity scale for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today. 2013;33(3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Qiu S, Dooley LM, Ma C. The relationship between challenge and hindrance stressors and emotional exhaustion: The moderating role of perceived servant leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;17(1):282. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Liden RC, Liao C, Wayne SJ. Does manager servant leadership lead to follower serving behaviors? It depends on follower self-interest. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2021;106(1):152–167. doi: 10.1037/apl0000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Gu JB, Liu HF. Servant leadership and employee creativity: The roles of psychological empowerment and work-family conflict. Current Psychology. 2019;38(6):1417–1427. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-0161-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Meng H, Yang S, Liu D. The influence of professional identity, job satisfaction, and work engagement on turnover intention among township health inspectors in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(5):988. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Hawk ST, Zhang X, Zhao H. Chinese preservice teachers’ professional identity links with education program performance: The roles of task value belief and learning motivations. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7:573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.