Abstract

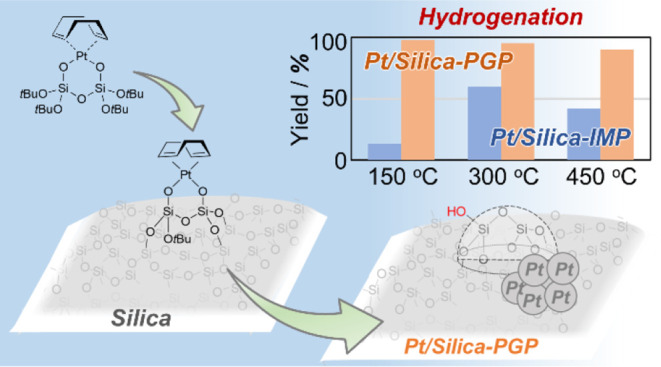

Supported platinum nanoparticles are currently the most functional catalysts applied in commercial chemical processes. Although investigations have been performed to improve the dispersion and thermal stability of Pt particles, it is challenging to apply amorphous silica supports to these systems owing to various Pt species derived from the non-uniform surface structure of the amorphous support. Herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of amorphous silica-supported Pt nanoparticles from (cod)Pt–disilicate complex (cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene), which forms bis-grafted surface Pt species regardless of surface heterogeneity. The synthesized Pt nanoparticles were highly dispersible and had higher hydrogenation activity than those prepared by the impregnation method, irrespective of the calcination and reduction temperatures. The high catalytic activity of the catalyst prepared at low temperatures (such as 150 °C) was attributed to the formation of Pt nanoparticles triggered by the reduction of cod ligands under H2 conditions, whereas that of the catalyst prepared at high temperatures (up to 450 °C) was due to the modification of the SiO2 surface by grafting of the (cod)Pt–disilicate complex.

Introduction

Supported metal nanoparticles are widely used as catalysts in various fields, such as the manufacture of bulk and fine chemicals, biomass conversion, and exhaust gas purification.1−4 An effective method for producing supported metal nanoparticle catalysts for these chemical processes involves the fabrication of highly dispersed metal particles, which maximizes the utilization efficiency of the chemical elements and, thus, minimizes the consumption of precious metals.5−8 In particular, supported Pt nanoparticles have been actively studied because of their extensive applications in hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, and oxidation reactions.5 Most of these studies focused on improving the particle dispersion9−13 and thermal stability14−16 of the supported metal nanoparticles and discussed the particle formation processes. In these studies, crystalline supports such as CeO2,14 porous materials,15 and solid supports with sophisticated properties16 were applied to improve the dispersion and stability of the supported metal nanoparticles. However, the dispersion and stability of the nanoparticles on amorphous supports, such as silica gel, are difficult to control because of the heterogeneous surface structures.17,18

The controlled growth of supported Pt nanoparticles from well-defined Pt surface species grafted on silica supports is a promising approach for producing uniform nanoparticles.19 This is because the pre-formation of well-defined grafted surface species can eliminate the possibility of agglomeration between Pt precursors during the particle formation processes, contrary to common approaches such as the impregnation (IMP) method (Scheme 1).20,21 Tilley et al. reported that calcination of Pt surface species prepared using (cod)Pt[OSi(OtBu)3]2 (cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene) and Me3Pt(tmeda)[OSi(OtBu)3] (tmeda = N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine) as molecular precursors on a silica support afforded highly dispersed Pt nanoparticles.22 Copéret et al. reported that (cod)Pt(X)(Y) [X, Y = Cl, Me, OSi(OtBu)3, and N(SiMe3)2] precursors affected not only the Pt loading and structure of grafted Pt complexes but also the properties of supported nanoparticles synthesized by reducing the grafted complexes under a H2 atmosphere.23 Gaemers et al. reported that grafting of the (dppe)PtMe2 [dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane] precursor yielded bis-grafted surface species, and the subsequent calcination in air produced supported Pt nanoparticles with smaller particle sizes, higher dispersions, and higher catalytic activity in toluene hydrogenation than those prepared from a (cod)PtMe2 precursor that forms mono-grafted surface species.24 These approaches effectively prevent the aggregation of Pt precursors during their conversion into nanoparticles, whereas the structure of the grafted surface species and the properties of the nanoparticles generated by their calcination were found to vary with the type of precursor complexes and surface conditions.

Scheme 1. Preparation of Silica-Supported Pt Nanoparticles from Grafted Pt Surface Species.

Recently, we developed a Pt complex with a bidentate disilicate ligand as a novel molecular precursor for grafting, which selectively formed bis-grafted surface species on silica supports irrespective of the surface heterogeneity, as shown in Scheme 1 (right).25 Because the grafting of the Pt–disilicate complex proceeds by a substitution reaction on the silicon atoms of the disilicate ligand with surface silanols, the metal center is indirectly involved in the bond formation for grafting. In addition, the disilicate ligand consists of SiO4 components similar to that of silica. Therefore, we call this approach the pseudo-grafted precursor (PGP) method. The grafted complexes obtained by the PGP method retain the six-membered chelate structure of the precursor. Hence, the electronic state of each surface species is largely unaffected by the conditions of the silica surface. We expected that this type of Pt-containing molecular precursor can provide finer nanoparticles upon calcination. In this study, we report the controlled growth of supported Pt nanoparticles from Pt–disilicate complexes grafted onto amorphous silica prepared by the PGP method. We further discuss the effects of the calcination/reduction conditions and Pt loading on the properties of the produced nanoparticles.

Experimental Section

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all preparations were performed under a N2 atmosphere using standard Schlenk and glovebox techniques. Anhydrous and deoxygenated solvents were used throughout the preparation. A (cod)Pt–disilicate complex was prepared according to a previously reported procedure.25 Fumed silica (Degussa Aerosil-200, 200 m2 g–1) was used as the silica support.

Grafting of the (cod)Pt–Disilicate Complex onto Silica

Aerosil-200 was added to a glass flask to remove the water adsorbed on silica supports, and pretreatment was performed at 120 °C for 1 h under high vacuum. Toluene was added into a flask under an Ar atmosphere and stirred for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, 1, 3, and 5 wt % of the (cod)Pt–disilicate complex in toluene was added dropwise to the support. After stirring at room temperature for 24 h, the product was collected via filtration, washed with toluene, and dried at room temperature under a high vacuum. The resulting samples, 1, 3, and 5 wt % (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2, were stored in a glovebox.

Preparation of Silica-Supported Pt Nanoparticles from Grafted Pt Surface Species (Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal)

First, (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2 (1.0 g) was placed in an alumina boat and heated under oxygen flow conditions (50 mL min–1) in a horizontal tube furnace by increasing the temperature from ambient temperature to 150, 300, and 450 °C at a rate of 1.0 °C min–1 and holding at the set temperature for 2 h. The samples were then cooled to room temperature to obtain the Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal (0.95 g) product as a powder. Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal refers to the silica-supported Pt nanoparticles prepared at a specific calcination temperature (Tcal) from the grafted Pt surface species prepared by the PGP method.

Preparation of Silica-Supported Pt Nanoparticles by the Incipient Wetness IMP Method (Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal)

Aerosil-200 (2.0 g) was placed on a baking dish, and an aqueous solution containing [(NH3)4Pt](NO3)2 (Johnson Matthey) was added for each loading amount. The impregnated sample was dried at 100 °C in an oven and then placed in an alumina boat. Subsequently, the sample was heated under oxygen flow conditions (50 mL min–1) in a horizontal tube furnace by increasing the temperature from ambient temperature to 150, 300, and 450 °C at a rate of 1.0 °C min–1, followed by treatment at the set temperature for 2 h. Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal refers to the silica-supported Pt nanoparticles prepared by the IMP method.

Characterization of Silica-Supported Pt Nanoparticles

To clarify the properties of the silica supports and produced Pt particles, Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal and Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal were subjected to powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis using D8 DISCOVER and XRD2-CS ECO (Bruker) instruments with a Cu Kα X-ray source (50 kV, 1.0 mA), acrylic resin plate, and two-dimensional detector (VANTEC-500). Elemental analysis of the Pt content loaded onto silica supports was performed by inductively coupled plasma spectrometry using a Shimadzu ICPS-8000 instrument. The target materials were dissolved in nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and then 50% aq. KOH to prepare the measurement samples. The amount of CO molecules adsorbed on Pt/SiO2-PGP and Pt/SiO2-IMP was measured using a BELCAT-B (MicrotracBEL) system. The measurement samples (approximately 0.3–0.4 g) were placed into a sample holder and reduced at 450 °C for 60 min under a 10% H2/Ar flow of 30 mL min–1. The samples were then cooled to 50 °C under a He flow of 30 mL min–1. CO/He [10/90% (v/v)] was intermittently injected into the holder at 50 °C until the amount of CO exiting the holder was constant. The calculation method was adapted from a previous study.26 The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area (SBET) was estimated from the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms recorded at −196 °C on a Belsorp-mini II instrument (MicrotracBEL). The sample (20 mg) was heated to 80 °C in vacuo for 2 h before measurement to remove the adsorbed water. Solution 1H NMR spectra (1H, 600 MHz) were recorded using an AVANCE III HD 600 spectrometer (Bruker). Chemical shifts were reported in δ (ppm) and referenced with respect to the residual solvent signals in 1H (7.16 ppm for C6D6) as an external standard. In addition, 13C cross-polarization magic-angle-spinning (CP MAS) NMR spectra were obtained using an AVANCE II 400 spectrometer (Bruker) with a 4.0 mm MAS probe. CP MAS was performed at a rotation speed of 12.5 kHz. The 13C chemical shifts were referenced with respect to an adamantane standard. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were performed using a Tecnai Osiris (FEI) instrument with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using a JEOL JEM-2010 instrument with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The surface-averaged Pt diameters and particle distributions were determined based on more than 200 particles in different regions of the TEM images. For Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), each sample (20 mg) was pressed and placed in an IR cell in a grove box. Spectra were then recorded and averaged over 64 scans using a FT/IR-6800 spectrometer (JASCO) equipped with a triglycine sulfate detector.

Hydrogenation of Cyclooctene

Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal and Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal samples were placed in a glass Schlenk tube and pre-treated using an electric furnace under a H2 flow (40 mL min–1) for 1 h at reduction temperatures (Tred) of 150, 300, and 450 °C to produce Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal_Tred and Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal_Tred samples, respectively. After cooling to room temperature under an Ar atmosphere, cyclooctene (2.45 mmol), mesitylene (0.86 mmol) internal standard, and isopropanol (4 mL) solvent were introduced into the Schlenk tube, and the atmosphere was subsequently changed to H2. The mixture was stirred at room temperature under 1 atm H2 and sampled at predetermined times.

Determination of Silanol Amount

The content of surface silanol was determined by reacting the samples with Mg(CH2Ph)2(THF)2 and then quantifying the toluene produced.24 The measurement sample, Aerosil-200, 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP, and 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP were pre-treated under two different conditions, specifically, dehydration and calcination/reduction. The dehydrated samples were pre-treated in a glass Schlenk tube at 80 °C for 4 h under vacuum. Conversely, the calcination/reduction samples (Sample name_Tcal_Tred) were calcined at 450 °C for 2 h and then reduced under H2 flow (40 mL min–1) at 450 °C for 1 h. These samples (15 mg) were placed in a J-Young NMR tube, and C6D6 (100 μL) was subsequently added to prepare a slurry. A C6D6 solution of ferrocene as an internal standard and Mg(CH2C6H5)2(THF)2 was added to the slurry, and the quantity of generated toluene was quantified by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Results and Discussion

Effect of Calcination and Reduction Conditions on Nanoparticle Growth and Catalytic Activity

Silica-supported Pt nanoparticles were prepared by the PGP and IMP methods with a 3 wt % initial Pt loading and calcined at 150, 300, or 450 °C to examine the effect of calcination temperature on the size and morphology of the produced Pt nanoparticles. Table 1 summarizes SBET and particle sizes obtained from the N2 adsorption–desorption results and STEM images of Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal and Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal, respectively. The surface areas ranged from 176 to 191 m2 g–1 and varied slightly depending on the preparation method and calcination temperature. In addition, STEM images with particle size histograms are shown in Figure 1. Pt particles were barely observed for the samples calcined at 150 °C, irrespective of the preparation method (Figure 1a,b). Although the EDX maps of the samples confirmed the presence of Pt species, the intensity of the signals was weak, and the Pt content in the samples estimated by EDX analysis (0.30 ± 0.18 wt % for Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 and 0.31 ± 0.18 wt % for Pt/SiO2-IMP_150) was significantly less than that used during preparation (Figure S1). However, the Pt loading amount determined by ICP-AES (2.7 wt % for Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 and 2.8 wt % for Pt/SiO2-IMP_150) was almost consistent with that used during preparation. These results indicate that the Pt species exist in the form of Pt nanoparticles smaller than 0.5 nm and/or unreacted Pt surface complexes when calcined at 150 °C, which cannot be detected by STEM–EDX. In the STEM images of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 (Figure 1c) and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 (Figure 1d), Pt nanoparticles were observed; the nanoparticles of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 had a narrower size distribution and a smaller average particle size than those of Pt/SiO2-IMP_300. The elemental contents estimated from EDX maps also show a clear difference in the Pt distributions (Figure S2). The Pt content was 2.6 ± 0.9 wt % in Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 (Figure S2a), which was almost identical to that of the ICP (3.2 wt %) and preparation (3 wt %) values, indicating a uniform Pt distribution in this sample. In contrast, the Pt content of Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 depended greatly on the EDX map used. For example, the Pt content estimated from an image with highly dispersed nanoparticles was 1.9 ± 0.7 wt % (Figure S2b), while that estimated from an image with more agglomerated particles was 3.9 ± 1.2 wt % (Figure S2c). This confirms a non-uniform distribution of Pt particles in Pt/SiO2-IMP_300. Although no significant difference was observed in the particle size and size distributions of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450 compared to those of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 (Figure 1e), the particle size of Pt/SiO2-IMP_450 was greater than that of Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 due to sintering at the higher temperature (Figure 1f). The more uniform dispersion of nanoparticles in Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal compared to that in Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal is attributed to the good dispersion of the pre-formed Pt surface complexes, (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2, prior to calcination.22,23

Table 1. Structure Parameters of the 3 wt % Pt Supported Catalysts.

| samples | Pt content (mmol g–1)a | SBET (m2 g–1) | particle size (nm)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 192 | ||

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 | 2.7 | 184 | 0.9 |

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 | 3.2 | 182 | 1.6 |

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_450 | 2.9 | 176 | 1.7 |

| Pt/SiO2-IMP_150 | 2.8 | 186 | 1.3 |

| Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 | 3.2 | 191 | 2.5 |

| Pt/SiO2-IMP_450 | 2.8 | 182 | 2.8 |

Determined by the ICP-AES measurement.

Calculated by counting over 200 white dots from the STEM images.

Figure 1.

STEM images and particle size distributions of (a) Pt/SiO2-PGP_150, (b) Pt/SiO2-IMP_150, (c) Pt/SiO2-PGP_300, (d) Pt/SiO2-IMP_300, (e) Pt/SiO2-PGP_450, and (f) Pt/SiO2-IMP_450.

The supported Pt nanoparticles were reduced under a H2 atmosphere at the same temperature as calcination, then the catalytic performance was evaluated by the hydrogenation of cyclooctene. The time profiles of cyclooctene hydrogenation over 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal_Tred and Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal_Tred are shown in Figure 2a,b, respectively. Pt/SiO2-PGP_150_150, Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300, and Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450, pre-treated at different temperatures, had similar catalytic activities and reached over 90% yield within 60 min. In contrast, the catalytic activity of 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal_Tred significantly differed depending on the pretreatment temperature. A low yield of 13% was observed after 60 min in the presence of Pt/SiO2-IMP_150_150, whereas Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 gave a moderate yield of 60%, and Pt/SiO2-IMP_450_450 gave a low yield of 42%. These results with Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal_Tred are consistent with the previous report that the dispersion of Pt species prepared by the IMP method depends on the calcination temperature.27 It is noteworthy that the yields obtained with Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal_Tred were higher than those obtained with Pt/SiO2-IMP_Tcal_Tred, regardless of the pretreatment temperature.

Figure 2.

Hydrogenation of cyclooctene over (a) Pt/SiO2-PGP and (b) Pt/SiO2-IMP prepared by various pretreatment conditions [calcined and reduced at 150 °C (blue square), 300 °C (black circle), and 450 °C (red triangle)].

As shown in Figure 1a,b, the STEM images of Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_150 showed that only a portion of the Pt species was transformed into Pt nanoparticles with detectable particle sizes by calcination at 150 °C. Nevertheless, Pt/SiO2-PGP_150_150 had a catalytic activity comparable to that of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 and Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450, in which Pt particles were sufficiently formed. The reaction rate of olefin hydrogenation catalyzed by Pt nanoparticles is known to be unaffected by the type of Pt species and substrate concentration but dependent on the number of Pt atoms on the particle surface.28 A significantly low yield obtained with Pt/SiO2-IMP_150_150 indicates minimal particle growth since the IMP method using Pt(NH3)4(NO3)2 usually requires a temperature above 200 °C or 150–200 °C under an O2 or H2 atmosphere to fabricate the nanoparticles.29 In contrast, Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 presumably contained highly active Pt species such as tiny particles or underwent particle growth under reduction and/or alkene hydrogenation conditions. To elucidate the particle formation process in Pt/SiO2-PGP calcined at 150 °C, Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 was analyzed by solid-state NMR (Figure S3). The 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum showed peaks derived from cod and tBuO groups, and the chemical shift values were similar to those of (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2 before calcination, indicating that the (cod)Pt–disilicate complexes grafted on silica remain in Pt/SiO2-PGP_150. Conversely, peaks derived from the cod ligand were not observed in the 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300; however, peaks attributed to the tBuO group were detected. To investigate whether the particle growth occurs during the reduction process, we prepared Pt/SiO2-PGP_150(Ar) pre-treated at 150 °C under an Ar atmosphere without reduction and Pt/SiO2-PGP_none_150 directly reduced at 150 °C without calcination. Furthermore, their catalytic activities for cyclooctene hydrogenation were compared with those of (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2, Pt/SiO2-PGP_150, Pt/SiO2-PGP_150_150, and Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 (Table 2). The (cod)Pt-disilicate on the SiO2 sample had slight hydrogenation activity, confirming that the Pt particles, and not the surface Pt complexes, were the major active species under the hydrogenation conditions. Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 and Pt/SiO2-PGP_150(Ar) also gave very low yields, whereas Pt/SiO2-PGP_none_150 and Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 had high catalytic activities, similar to Pt/SiO2-PGP_150_150. These results indicate that the particle growth triggered by thermal dissociation of the cod ligand from the Pt center occurs at 300 °C and not at 150 °C. However, hydrogenation of the cod ligand also triggers particle growth, which can proceed even at 150 °C. During the preparation of Pt/SiO2-PGP_none_150, the formation of cyclooctane, produced by the hydrogenation of the cod ligand, was observed by GC–MS (Figure S4), and the 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum of Pt/SiO2-PGP_none_150 had few peaks derived from the cod ligand, similar to Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 (Figure S3e). Finally, TEM images of Pt/SiO2_none_150 confirmed the formation of Pt particles (Figure S5). Thus, we concluded that Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 underwent particle growth during the reduction pretreatment at 150 °C before olefin hydrogenation.

Table 2. Results of Cyclooctene Hydrogenation Activity of Samples Prepared by Various Pretreatment Conditions.

| samples | gas conditions | treatment time (h) | yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2 | 3.4 | ||

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_150 | O2 | 2 | 4.6 |

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_150(Ar) | Ar | 2 | 5.4 |

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_none_150 | H2 | 1 | 99 |

| Pt/SO2-PGP_150_150 | O2, then H2 | 2, then 1 | >99 |

| Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 | O2 | 2 | 99 |

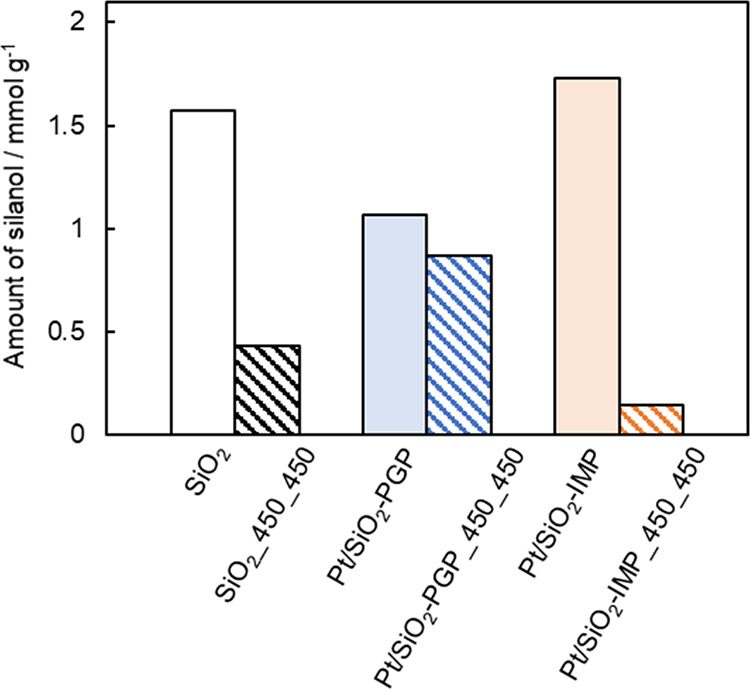

Next, we discuss the differences in the sizes of the nanoparticles produced by the PGP and IMP methods and their catalytic hydrogenation activity when calcined and reduced at 450 °C. The higher catalytic activity of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450 than Pt/SiO2-IMP_450_450 (Figure 2) and narrower size distribution and smaller average particle size of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450 than Pt/SiO2-IMP_450 (Figure 1) was initially attributed to the uniform grafting of Pt atoms from (cod)Pt-disilicate onto SiO2 by two Pt–O–Si bonds during PGP (Scheme 1), which increases the thermal stability during particle growth. However, the Pt–O bonds of Pt(II) complexes are reported to be readily reduced by H2, even at 1 °C.30 Thus, the number of Pt–O bonds may not contribute to the thermal stability of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450. Lambrecht et al. evaluated the relationship between the adsorption energy of Pt particles on amorphous SiO2 supports and the amount of surface silanol using first-principles density functional theory calculations.17 They suggested that the adhesion energy between Pt nanoparticles and supports, which affects the thermal stability, increases with the increasing surface silanol content. Therefore, the surface silanol content in each sample before and after calcination and reduction at 450 °C was determined by the reaction between the sample and Mg(CH2Ph)2(THF)2,24 and the results are shown in Figure 3. The surface silanol content of the parent SiO2 changed from 1.57 to 0.43 mmol g–1 after calcination and reduction. The silanol content of Pt/SiO2-PGP before calcination and reduction was 1.07 mmol g–1, which was less than that of the parent SiO2 (change of 0.50 mmol g–1). The decrease in the silanol content was close to the theoretical consumption (0.61 mmol g–1), assuming that (cod)Pt–disilicate complexes are completely grafted on SiO2 by quadruple substitutions on the disilicate ligand.25 Remarkably, the silanol content of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450 (0.8 mmol g–1) was higher than that of SiO2_450_450 (0.43 mmol g–1). In contrast, the silanol content in Pt/SiO2-IMP before treatment (1.7 mmol g–1) was almost the same as that in SiO2 before treatment (1.57 mmol g–1). Because the Pt species and silica supports are dispersed in an aqueous solution during IMP, the silica supports adsorb the Pt species on the silanol and are rehydrated by water.31,32 In addition, the silanol content of Pt/SiO2-IMP_450_450 significantly decreased to 0.15 mmol g–1 compared to that before the treatment.

Figure 3.

Estimated silanol amount in Pt/SiO2 before and after calcination/reduction.

It is well known that several silanol species are present on SiO2, and their proportions are changed by heat treatment.33 Therefore, FT-IR measurements were performed to confirm the silanol species on each sample (Figure S6). Regardless of the preparation method, samples before calcination/reduction at 450 °C showed a sharp peak at 3740 cm–1 and a broad peak around 3500 cm–1, attributed to isolated silanols and hydrogen-bonded silanols, respectively.34 The spectrum of Pt/SiO2-PGP has several peaks around 2800–3000 cm–1, which were assigned to CH stretching vibrations, supporting the presence of cod and tBuO groups as observed in the 13C CP MAS NMR spectrum (Figure S3b). After the calcination/reduction processes, the peaks around 2800–3000 cm–1 were not observed for Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450, which also supports nanoparticle formation, and the peaks at 3740 cm–1 and around 3500 cm–1 remained. Although it is difficult to accurately quantify the amount of silanol from the absorbance in the IR spectra, comparison of the spectra shows that Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450 contains a larger amount of silanol than Pt/SiO2-IMP_450_450, which is consistent with the silanol contents determined from Figure 3. Although the details are currently unclear, we assume that grafting of (cod)Pt–disilicate complexes, which contain a disilicate moiety composed of Si–O components similar to silica, reforms the SiO2 surface during the grafting, allowing it to maintain a high silanol content even after calcination/reduction at 450 °C, and the high silanol content contributes to the high dispersion of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450 and the high catalytic activity of Pt/SiO2-PGP_450_450.

Effect of Pt Loading and Types of Supports

The particle growth of supported metal species is highly dependent on the metal loading.35 Herein, we determined the effect of Pt loading on the aggregation behavior of the Pt nanoparticles using a (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2 prepared by the PGP method. Figure 4 shows STEM images and particle size distributions of 1 wt % and 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300. The average particle sizes of the samples with 1 wt % Pt loading were approximately 1.6 nm for both preparation methods (Figure 4a,b). For the samples with 5 wt % Pt, the average particle sizes of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 were 1.5 and 2.4 nm (Figure 4c,d), respectively, indicating that the average particle size of the sample prepared by PGP was smaller than that prepared by IMP, similar to the case with 3 wt % Pt loading.

Figure 4.

STEM image of (a) 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300, (b) 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300, (c) 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300, and (d) 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300.

The dispersion of Pt particles in Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 was evaluated by powder XRD measurements (Figure S7). While 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 showed two peaks at 2θ values of 40 and 46°, which are assigned to the (111) and (200) reflections of the face-centered cubic (fcc) PtO2 crystals,36 no obvious peaks were observed in the XRD pattern of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 even with 5 wt % Pt loading. Dispersions of Pt species in the samples calcined at 300 °C and then reduced at 450 °C were further determined by CO pulse adsorption (Table S1). Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_450 showed high dispersion for all Pt loadings (33.8% for 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP, 36.5% for 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP, and 34.1% for 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP), whereas Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_450 showed lower dispersion than those prepared by PGP; the Pt dispersion decreased with increasing Pt loading (27.1% for 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP, 18.4% for 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP, and 14.8% for 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP). These results suggest that the Pt species in Pt/SiO2-PGP_300 are highly dispersed, regardless of the Pt loading.

Figure 5 illustrates the hydrogenation of cyclooctene with time for each Pt loading. For 1, 3, and 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300, the yields at 45 min were 37, 99, and 99%, respectively (Figure 5a); however, the yields of 1, 3, and 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 were 13, 38, and 58%, respectively (Figure 5b). While the hydrogenation activity increased with increasing Pt loading in both samples, the turnover frequency (TOF) of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 was determined under more dilute conditions to evaluate the catalytic performance in more detail. Figure S8 shows the linear relationship between the yield of cyclooctene hydrogenation and the reaction time. The TOF of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 and Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 with respect to Pt loadings is summarized in Table 3. The TOF values of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 were 19.3, 18.6, and 18.6 mol (mol-Pt)−1 min–1 at Pt loadings of 1, 3, and 5 wt %, respectively. Notably, the calculated TOF was constant despite increasing the Pt loading, and the high activity was maintained even at a high Pt loading of 5 wt %. However, the TOF values of Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 were 5.3, 4.9, and 3.2 mol (mol-Pt)−1 min–1 at 1, 3, and 5 wt %, respectively. 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 showed low hydrogenation activity, despite the small particle size of 1.6 nm observed before reduction (Figure 4b). This result suggests that the reduction treatment of Pt/SiO2-IMP_300 to Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 promoted particle growth.37 Although the surface Pt content after reduction at 300 °C could not be determined with the available apparatus, the constant TOF of Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 for the total Pt content indirectly indicates that the average particle size and distributions are not dependent on the Pt loading.

Figure 5.

Hydrogenation of cyclooctene over Pt nanoparticles supported on (a) Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 and (b) Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 1 wt % (black circle), 3 wt % (blue square), and 5 wt % (red triangle).

Table 3. TOF of Cyclooctene Hydrogenation over Pt/SiO2-PGP and Pt/SiO2-IMP.

| Pt/SiO2 | TOF (mol (mol-Pt)−1 min–1) |

|---|---|

| 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 | 19.3 ± 0.8 |

| 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 | 18.6 ± 0.6 |

| 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-PGP_300_300 | 18.6 ± 0.5 |

| 1 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 | 5.3 ± 0.7 |

| 3 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 | 4.9 ± 0.3 |

| 5 wt % Pt/SiO2-IMP_300_300 | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

Conclusions

Silica-supported Pt nanoparticles were synthesized by controlled growth from (cod)Pt-disilicate on SiO2, which was prepared by immobilizing (cod)Pt–disilicate complex as a molecular precursor. Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal_Tred showed high hydrogenation activity even at a reduction temperature as low as 150 °C due to the nanoparticle formation triggered by hydrogenation of cod. Furthermore, the high hydrogenation activity was maintained even after heat treatment at approximately 450 °C. This thermal stability is attributed to the high silanol content maintained even after calcination/reduction at 450 °C. Finally, Pt/SiO2-PGP_Tcal_Tred had high hydrogenation activity independent of the Pt loading amount up to 5 wt %. The PGP method could be applied to other metal/amorphous support systems to provide catalytic activity at low temperatures and thermal stability on practical amorphous supports. This protocol could be extended to studies on more detailed particle-formation mechanisms of supported metal species and synthesis of nanoparticles of other transition metals supported on silica surfaces.

Acknowledgments

We thank the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) for partially supporting this research (grant no. JPNP16010). We thank Akira Takatsuki [National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST)] for the measurement of STEM and EDX.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c06262.

HAADF-STEM images and corresponding element maps, 13C CP MAS NMR spectra, GC–MS spectra, TEM images, FT-IR spectra, results of CO-pulse experiments, XRD patterns, and time-course of hydrogenation (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sattler J. J. H. B.; Ruiz-Martinez J.; Santillan-Jimenez E.; Weckhuysen B. M. Catalytic Dehydrogenation of Light Alkanes on Metals and Metal Oxides. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10613–10653. 10.1021/cr5002436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsanam P.; Peeters E.; Makshina E. V.; Parvulescu V. I.; Sels B. F. Advances in Porous and Nanoscale Catalysts for Viable Biomass Conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2366–2421. 10.1039/c8cs00452h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.; Cai S.; Gao M.; Hasegawa J.; Wang P.; Zhang J.; Shi L.; Zhang D. Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 by Using Novel Catalysts: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10916–10976. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco F.; Rettenmaier C.; Jeon H. S.; Roldan Cuenya B. R. Transition Metal-Based Catalysts for the Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: from Atoms and Molecules to Nanostructured Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6884–6946. 10.1039/d0cs00835d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Corma A. Metal Catalysts for Heterogeneous Catalysis: From Single Atoms to Nanoclusters and Nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4981–5079. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A.; Serna P. Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitro Compounds with Supported Gold Catalysts. Science 2006, 313, 332–334. 10.1126/science.1128383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. W.; Chen L. X.; Yang C. C.; Jiang Q. Atomic (Single, Double, and Triple Atoms) Catalysis: Frontiers, Opportunities, and Challenges. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 3492–3515. 10.1039/c8ta11416a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Zhou M.; Wang A.; Zhang T. Selective Hydrogenation over Supported Metal Catalysts: From Nanoparticles to Single Atoms. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 683–733. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L.; Wang X.; Chen Q.; Ye Y.; Zheng H.; Guo J.; Yin Y.; Gao C. Explaining the Size Dependence in Platinum-Nanoparticle-Catalyzed Hydrogenation Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15656–15661. 10.1002/anie.201609663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deraedt C.; Ye R.; Ralston W. T.; Toste F. D.; Somorjai G. A. Dendrimer-Stabilized Metal Nanoparticles as Efficient Catalysts for Reversible Dehydrogenation/Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18084–18092. 10.1021/jacs.7b10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Ji J.; Feng X.; Duan X.; Qian G.; Li P.; Zhou X.; Chen D.; Yuan W. Mechanistic Insight into Size-Dependent Activity and Durability in Pt/CNT Catalyzed Hydrolytic Dehydrogenation of Ammonia Borane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16736–16739. 10.1021/ja509778y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Lee S.; Kim H.-E.; Cho A.; Kim S.; Ye Y.; Han J.; Lee H.; Jang J. H.; Lee J. Investigation of the Support Effect in Atomically Dispersed Pt on WO3–x for Utilization of Pt in the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16038–16042. 10.1002/anie.201908122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.-L.; Shen S.-C.; Zhao S.; Ding Y.-W.; Chu S.-Q.; Chen P.; Lin Y.; Liang H.-W. Synthesis of Carbon-Supported Sub-2 Nanometer Bimetallic Catalysts by Strong Metal–Sulfur Interaction. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 7933–7939. 10.1039/d0sc02620d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L.; Mei D.; Xiong H.; Peng B.; Ren Z.; Hernandez X. I. P.; DeLaRiva A.; Wang M.; Engelhard M. H.; Kovarik L.; Datye A. K.; Wang Y. Activation of Surface Lattice Oxygen in Single-Atom Pt/CeO2 for Low-Temperature CO Oxidation. Science 2017, 358, 1419–1423. 10.1126/science.aao2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Díaz U.; Arenal R.; Agostini G.; Concepción P.; Corma A. Generation of Subnanometric Platinum with High Stability During Transformation of a 2D Zeolite into 3D. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 132–138. 10.1038/nmat4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye T.-N.; Xiao Z.; Li J.; Gong Y.; Abe H.; Niwa Y.; Sasase M.; Kitano M.; Hosono H. Stable Single Platinum Atoms Trapped in Subnanometer Cavities in 12CaO·7Al2O3 for Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1020. 10.1038/s41467-019-14216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing C. S.; Hartmann M. J.; Martin K. R.; Musto A. M.; Padinjarekutt S. J.; Weiss E. M.; Veser G.; McCarthy J. J.; Johnson J. K.; Lambrecht D. S. Structural and Electronic Properties of Pt13 Nanoclusters on Amorphous Silica Supports. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 2503–2512. 10.1021/jp5105104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith B. R.; Sanderson E. D.; Bean D.; Peters B. Isolated Catalyst Sites on Amorphous Supports: A Systematic Algorithm for Understanding Heterogeneities in Structure and Reactivity. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 204105. 10.1063/1.4807384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basset J. M.; Choplin A. Surface Organometallic Chemistry: A New Approach to Heterogeneous Catalysis?. J. Mol. Catal. 1983, 21, 95–108. 10.1016/0304-5102(93)80113-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copéret C. Single-Sites and Nanoparticles at Tailored Interfaces Prepared via Surface Organometallic Chemistry from Thermolytic Molecular Precursors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1697–1708. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi M.; Mezzetti A. Site Isolated Complexes of Late Transition Metals Grafted on Silica: Challenges and Chances for Synthesis and Catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 2724–2740. 10.1039/c4cy00450g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy D. A.; Jarupatrakorn J.; Rioux R. M.; Miller J. T.; McMurdo M. J.; McBee J. L.; Tupper K. A.; Tilley T. D. Site-Isolated Pt-SBA15 Materials from Tris(tert-butoxy)siloxy Complexes of Pt(II) and Pt(IV). Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 6517–6527. 10.1021/cm801598k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent P.; Veyre L.; Thieuleux C.; Donet S.; Copéret C. From Well-Defined Pt(II) Surface Species to the Controlled Growth of Silica Supported Pt Nanoparticles. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 238–248. 10.1039/c2dt31639k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonati M. L. M.; Douglas T. M.; Gaemers S.; Guo N. Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Properties of Novel Single-Site and Nanosized Platinum Catalysts. Organometallics 2012, 31, 5243–5251. 10.1021/om200778r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka Y.; Arai M.; Matsumoto K.; Nagashima H.; Takeuchi K.; Fukaya N.; Yasuda H.; Sato K.; Choi J.-C. Bidentate Disilicate Framework for Bis-Grafted Surface Species. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 12069–12077. 10.1002/chem.202101927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka T.; Miyazawa T.; Shimura K.; Hirata S. Preparation for Pt-Loaded Zeolite Catalysts Using w/o Microemulsion and Their Hydrocracking Behaviors on Fischer-Tropsch Product. Catalysts 2015, 5, 88–105. 10.3390/catal5010088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S.; Izuka M.; Takahashi A.; Ohshima M.; Kurokawa H.; Miura H. Pt Dispersion Control in Pt/SiO2 by Calcination Temperature Using Chloroplatinic Acid as Catalyst Precursor. Appl. Catal., A 2012, 427–428, 85–91. 10.1016/j.apcata.2012.03.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boudart M. Heterogeneous Catalysis by Metals. J. Mol. Catal. 1985, 30, 27–38. 10.1016/0304-5102(85)80014-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oudenhuijzen M. K.; Kooyman P. J.; Tappel B.; van Bokhoven J. A.; Koningsberger D. C. Understanding the Influence of the Pretreatment Procedure on Platinum Particle Size and Particle-Size Distribution for SiO2 Impregnated with [Pt2+(NH3)4](NO3–)2: A Combination of HRTEM, Mass Spectrometry, and Quick EXAFS. J. Catal. 2002, 205, 135–146. 10.1006/jcat.2001.3433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka A.; Sato A.; Mizuho Y.; Hirano M.; Komiya S. Synthesis and Structure of Novel Organo(siloxo)platinum Complexes. Facile Reduction by Dihydrogen. Chem. Lett. 1994, 23, 1641–1644. 10.1246/cl.1994.1641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roark R. D.; Kohler S. D.; Ekerdt J. G. Role of Silanol Groups in Dispersing Mo(VI) on Silica. Catal. Lett. 1992, 16, 71–76. 10.1007/bf00764356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R. S. Surface Functionality of Amorphous Silica by Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. 1958, 62, 1168–1178. 10.1021/j150568a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuravlev L. T. The Surface Chemistry of Amorphous Silica. Zhuravlev Model. Colloids Surf. A 2000, 173, 1–38. 10.1016/s0927-7757(00)00556-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann P.; Knözinger E. Novel aspects of mid and far IR Fourier spectroscopy applied to surface and adsorption studies on SiO2. Sur. Sci. 1987, 188, 181–198. 10.1016/S0039-6028(87)80150-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard C. P.; Otto K.; Gandhi H. S.; Ng K. Y. S. Effects of Support Material and Sulfation on Propane Oxidation Activity over Platinum. J. Catal. 1993, 144, 484–494. 10.1006/jcat.1993.1348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C.; Hara K.; Fukuoka A. Low-Temperature Oxidation of Ethylene over Platinum Nanoparticles Supported on Mesoporous Silica. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6265–6268. 10.1002/anie.201300496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A. F. S.; Hulea V.; Ayral A.; Chave T.; Nikitenko S. I.; Kooyman P. J.; Tichelaar F. D.; Abate S.; Perathoner S.; Desmazes P. L. Engineering of Silica-Supported Platinum Catalysts with Hierarchical Porosity Combining Latex Synthesis, Sonochemistry and Sol-Gel Process – II. Catalytic Performance. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 256, 227–234. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.