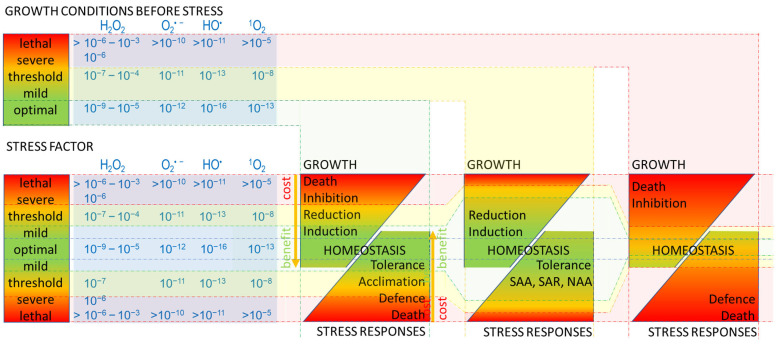

Figure 1.

Response to the stress factor is determined by growth conditions prior to stress, the intensity of the stress factor, and ROS generated under stress. The higher intensity of the ‘stress’ factor ranging from optimal (green) to lethal (red), the higher is ROS level in cells and organisms (blue panel). ROS type (e.g., H2O2, O2•−, HO•, 1O2) and concentration (e.g., lower for animals and humans 10−9–10−6 M H2O2; than for plants 10−6–10−3 M H2O2) can influence the sensitivity of the organism, thus controlling its growth and stress responses from homeostasis (green) to death (red). ‘Homeostasis’ is a balance of metabolic processes regulating ‘growth’ and ‘stress responses’. ‘Mild stress’ can be a ‘benefit’ to cells and organisms; activates signalling pathways, and metabolic processes; and energy (yellow arrows) is used to ‘induce’ growth and maintain ‘tolerance’ response to stress [9,11,12,15,88,89]. Along with increasing the pressure of ‘stress’ up to the ‘threshold’ level, the redirection of metabolic energy, required for ‘acclimation’ and ‘defence’, results in lower energy availability for ‘growth’ (followed by its ‘reduction’ or ‘inhibition’); and vice versa, growth ‘induction’ limits ‘stress responses’. However, the effect of stress is still beneficial, as both ‘growth’ and ‘acclimation’ can be separate strategies to survive stress. Exceeding the ‘threshold’ stress impacts negatively; the ‘cost’ of either maintaining ‘growth’ or induction of ‘defence’ responses, or both, is too high for cells and organisms under ‘severe’ stress. ‘Inhibition’ of the growth has feedback through a further limitation of the metabolic energy supply. A ‘lethal’ level of stress leads to the ‘death’ of the cell and the whole organism. The ‘threshold’ of stress can be shifted, as it is dependent on the ‘growth condition before stress’. ‘Optimal’ growth conditions prior to stress factor ensure ‘benefits’ from a level of ROS, that are induced under no-stress (optimal) conditions or under ‘mild’ stress factor (green filling indicating beneficial growth and stress responses). ‘Mild’/‘threshold’ stress during ‘growth conditions before stress’ shifts the ‘benefit’ responses (wider green filling) and reduces ‘costs’ (thinner red filling), during the following stress event, and induces ROS-dependent systemic or network acquired acclimatization (‘SAA’, ‘NAA’) and systemic acquired defence (‘SAR’) [9,11,12,15,88,89]. In contrast, ‘severe’ or ‘lethal’ growth conditions prior to stress negatively impact growth and stress responses (growth inhibition and defence failure, leading to death) even at ROS levels induced under mild stress (wide red filling).