Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease. Lupus nephritis (LN) is a major risk factor for mortality in SLE, and glomerular “full-house” immunofluorescence staining is a well-known characteristic of LN. However, some cases of non-lupus glomerulonephritis can also present with a “full-house” immunofluorescence pattern. We recently encountered a patient with full-house nephropathy (FHN) during adalimumab administration for Crohn's disease. IgA nephropathy or idiopathic FHN was diagnosed, and treatment with steroids was started, after which there was improvement in proteinuria. The prognosis of FHN has been reported to be poor; therefore, aggressive treatment is required for such patients.

Keywords: full-house nephropathy, Crohn's disease, IgA nephropathy

Introduction

A “full-house” immunofluorescence pattern is a typical finding in renal biopsies of patients with lupus nephritis (LN) (1). However, some cases of non-lupus nephropathy can also present with the same full-house pattern. The clinicopathological spectrum of non-lupus full-house nephropathy (FHN) was first defined by Wen and Chen (2). However, the pathogenesis, classification, clinical course, and treatment of FHN are still unclear.

Previous reports have suggested that inflammatory bowel diseases, including Crohn's disease, may occur in association with renal parenchymal diseases, such as IgA nephropathy (IgAN). Crohn's disease-related glomerulonephritis has been widely reported to be associated with the severity of Crohn's disease (3,4). In addition, anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) therapies, including adalimumab, are widely used to treat a variety of inflammatory diseases and have significantly improved treatment outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. However, anti-TNF-α therapies can also induce biologics-induced autoimmune renal disorders (AIRDs) (5), including drug-induced lupus erythematosus.

We herein report a case of FHN with no serological evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a patient with Crohn's disease. This is the first reported case of FHN with Crohn's disease.

Case Report

The patient was a 29-year-old Japanese woman with no personal or family history of renal disease. She had been diagnosed with Crohn's disease at 19 years old. Thereafter, she underwent treatment for Crohn's disease with mesalazine and salazosulfapyridine. She had been treated with adalimumab (40 mg subcutaneously every 2 weeks) since she was 21 years old. At 28 years old, her Crohn's disease was in remission, without skin symptoms such as erythema nodosum or joint symptoms. However, the patient slowly developed foot edema, proteinuria (2.9 g/gCr) and hematuria (20-29/high-power field). C3 and C4 complement levels were not low, and serum creatinine was 0.8 mg/dL (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory Findings on Admission.

| Parameter | Value (reference range) | Parameter | Value (reference range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (×104/μL) | 5,600 (3,500-9,100) | HbsAg | Negative | |||

| Red blood cells (×104/μL) | 399 (395-465) | HbsAb | Negative | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 (11.3-15.2) | HbeAb | Negative | |||

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.1 (36.0-47.0) | HCVAb | Negative | |||

| Platelet count (×104/μL) | 25.3 (13.0-36.9) | Cryogloblin | Negative | |||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.6 (6.7-8.3) | Anti nuclear antibody | Negative | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 (3.9-4.9) | Anti dsDNA (IU/mL) | <1.2 (<10) | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 10 (8-20) | Anti SS-A (U/mL) | 1.9 (<7.0) | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.58 (0.47-0.79) | Anti-SS-B (U/mL) | <1.0 (<10.0) | |||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138 (137-147) | Anti-Sm | Negative | |||

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.8 (3.5-5.0) | Anti-histon (Units) | <1.0 (<1.0) | |||

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 108 (98-108) | MPO-ANCA (U/mL) | <1.0 (<3.5) | |||

| Total bilirubin (mg/L) | 0.9 (0.2-1.2) | PR3-ANCA (U/mL) | <1.0 (<2.0) | |||

| AST (IU/L) | 18 (7-38) | <Urinalysis> | ||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 18 (4-44) | Protein | 4+ | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 162 (150-219) | Occult blood | 3+ | |||

| Hemoglobin A1c (JDS) (%) | 5.0 (4.6-6.2) | Glucose | Negative | |||

| CH50 (U/mL) | 43.1 (30-45) | Red blood cell (/HPF) | 5-9 | |||

| C3 (mg/dL) | 94.4 (65.0-135) | White blood cell (/HPF) | Negative | |||

| C4 (mg/dL) | 21.6 (11.0-34.0) | Red blood cell cast | 1+ | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.03(<5) | Protein excretion (g/gCr) | 2.4 | |||

| IgG (mg/dL) | 661 (850-1,700) | Protein excretion (g/day) | 2.89 | |||

| IgA (mg/dL) | 306 (110-410) | Bence-Jones protein | Negative | |||

| IgM (mg/dL) | 89 (46-260) | Selectivity index | 0.21 |

Due to these findings, a kidney biopsy was performed. Light microscopy revealed 19 glomeruli, of which 5 exhibited global glomerulosclerosis, and 1 was a crescentic glomerulus. Approximately two-thirds of the glomeruli had mesangial proliferation and subendothelial deposits. In the interstitium, lymphocytic aggregation was found around the sclerotic glomeruli, and fibrosis was observed in approximately 40% of the interstitium. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed diffuse, global and granular staining of the glomerular tuft mesangial region with IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q and C3 (Fig. 1, 2). Electron microscopy revealed electron-deposits in the mesangial region (Fig. 3).

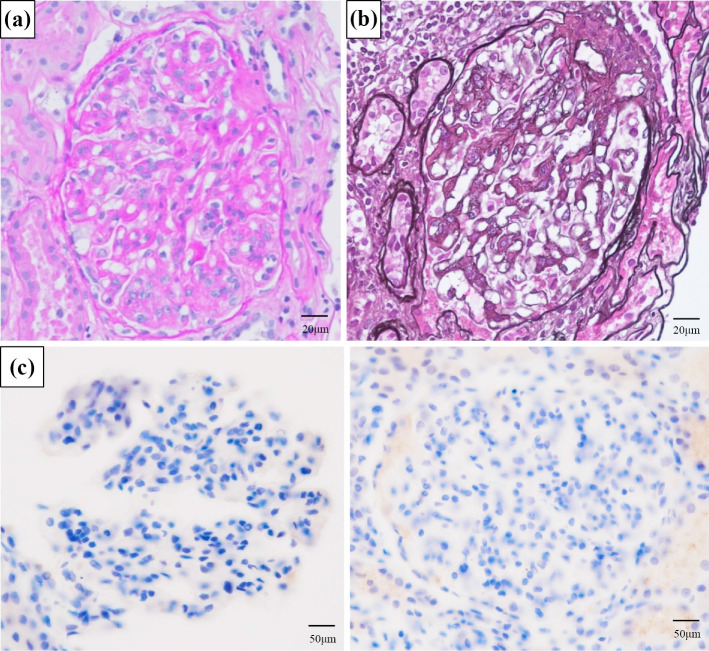

Figure 1.

Light microscopy revealed diffuse mesangial proliferative nephritis with subendothelial deposition. (a) Periodic acid-Schiff stain. (b) Periodic acid methenamine stain. (c) Granular deposition in kappa and lambda light chain staining was negative in the glomerular tuft mesangial region and partial endothelium.

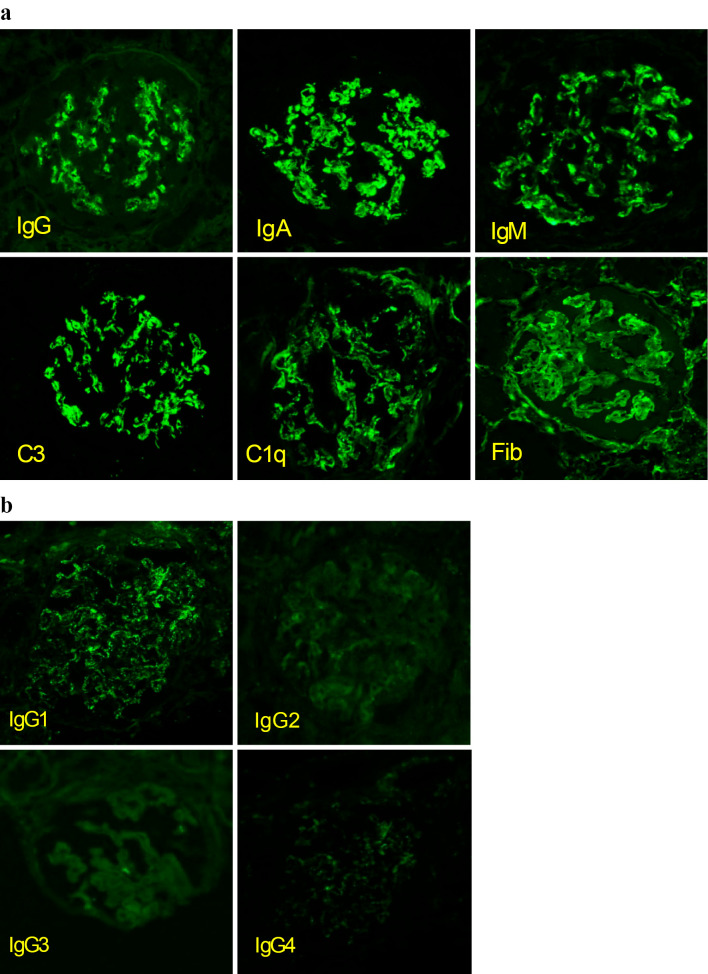

Figure 2.

(a) Immunofluorescent microscopy showed granular deposition of IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, and Fib in the glomerular tuft mesangial region and partial endothelium. (b) An immunofluorescent microscopic examination of IgG subclasses showed positive staining for IgG1.

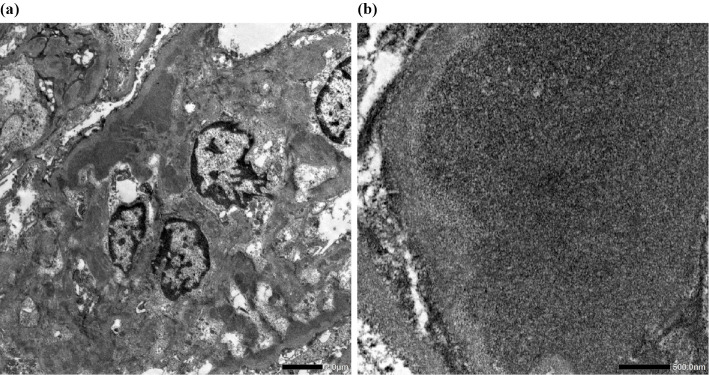

Figure 3.

(a) Electron microscopy revealed electron-deposits in the mesangial region. (b) Fingerprint structures were not found.

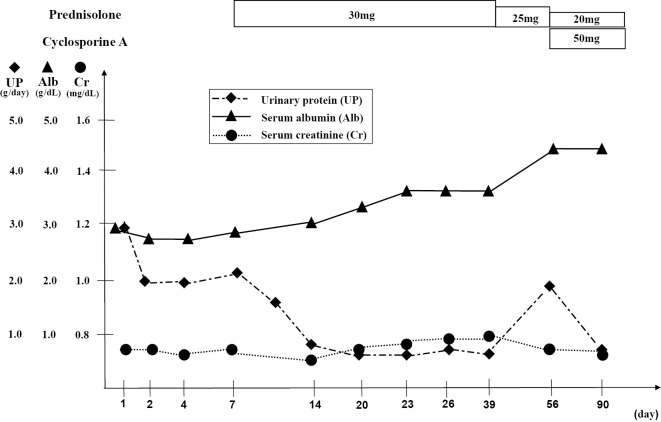

No antibodies or symptoms, such as butterfly rash, of SLE were detected, and the patient had no history of infection. Therefore, we diagnosed her with FHN and started oral steroids (prednisolone, 30 mg/day), after which her proteinuria improved to 0.6 g/gCr (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Clinical course.

Discussion

Glomerular “full-house” immunofluorescent staining is characteristic of LN. Non-lupus FHN is characterized by histopathological findings in the absence of clinical or serological evidence of SLE. Rijnink et al. classified non-lupus FHN as idiopathic FHN and secondary non-lupus FHN, with secondary non-lupus FHN considered to be due to membranous nephropathy (MN), IgAN, infection-related glomerulonephritis (IRGN) or anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis (6). Adalimumab is a biologic that can induce AIRDs, but no clinical trials have found an association between adalimumab and FHN.

IRGN, MN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) and C1q nephropathy were excluded based on the absence of clinical findings and immunofluorescence patterns. Immunotactoid glomerulopathy was excluded based on electron microscopy findings. Strong IgA and C3 signals were found on direct immunofluorescence, suggesting FHN secondary to IgAN or idiopathic FHN as possible diagnoses. IgAN is the most common chronic glomerulonephritis observed with inflammatory bowel disease (7), and a case of IgAN induced by adalimumab was recently reported (8). In the present case, FHN secondary to IgAN seemed to be the most likely diagnosis. However, hemispherical deposits, a characteristic of IgA nephropathy, were not observed on light microscopy.

It is rare to have simultaneous positive findings of IgG and C1q in immunofluorescence with typical IgA nephropathy. Furthermore, electron-dense deposits in the mesangial region were observed on microscopy. Tubuloreticular inclusions (TRIs) and fingerprint structure were not found. An immunofluorescent microscopic examination of the IgG subclasses showed positive staining for IgG1. Consequently, these detailed and comprehensive results led to the diagnosis of this case as FHN.

The concept of FHN has been proposed in patients who present with a “full-house” immunofluorescence pattern without serological abnormalities or clinical symptoms of SLE, with some cases remaining localized in the kidney and others progressing to SLE after several years (2,9-12) (Table 2). Ruggiero et al. reported that most Italian adolescents with FHN with typical histological features of LN had a good renal outcome after treatment for LN (13). However, Rijnink et al. found that idiopathic non-lupus FHN compared with lupus FHN was an independent risk factor for end-stage renal disease (6).

Table 2.

Classification of Non-lupus Full House Nephropathy.

| Reference | Number of cases | Renal biopsy | Cases developing SLE | IgG subclass | Tubuloreticular inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (12) | 3 | Mesangial GN (1) Membranous GN (2) |

1 | Unknown | Unknown |

| (11) | 17 | Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (1) Membranous GN (4) Mesangial GN (3) Focal GN (1) Diffuse proliferative GN (8) |

3 | Unknown | Positive for 2 cases that would later develop SLE |

| (14) | 6 | Diffuse mesangial GN (3) Membranous GN (2) Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (1) |

None | Unknown | Negative |

| (2) | 24 | Membranous GN (11) Membranoproliferative GN (3) Diffuse proliferative GN (6) Focal mesangial GN (4) |

2 | Unknown | Negative |

| (6) | 32 | Membranous GN (12) Primary full house nephropathy (20) |

None | Unknown | Positive for 2 cases (14) |

| (15) | 12 | Diffuse proliferative GN (11) Membranous GN (1) |

None | Unknown | Negative |

| (10) | 1 | Diffuse proliferative GN (1) | None | Unknown | Negative |

| Present case | 1 | Mesangial GN (1) | None | IgG1 | Negative |

GN: glomerulonephritis

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, we performed electron microscopy and evaluated the IgG subclass using paraffin-embedded tissue sections, as no glomeruli were available in glutaraldehyde-fixed tissue. Second, it was not possible to perform an immunofluorescent analysis for C4 due to limitations at our institution.

This is the first report of the development of non-lupus FHN during treatment of Crohn's disease with adalimumab.

This report does not include any experiments on humans or animals. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of relevant information in this case report. All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution at which the work was conducted and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to the nephrologists and nursing staff at Osaka City University Hospital and to the patient for their assistance with this case.

References

- 1. Cameron JS. Lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 413-424, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wen YK, Chen ML. Clinicopathological study of originally non-lupus “full-house” nephropathy. Ren Fail 32: 1025-1030, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Filipoulos V, Trompouki S, Hadjiyannakos D, Paraskevakou H, Kamperoglou D, Vlassopoulos D. IgA nephropathy in association with Crohn's disease: a case report and brief review of the literature. Ren Fail 32: 523-527, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forshaw MJ, Guirguis O, Hennigan TW. IgA nephropathy in association with Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 20: 463-465, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Piga M, Chessa E, Ibba V, et al. Biologics-induced autoimmune renal disorders in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases: systematic literature review and analysis of a monocentric cohort. Autoimmun Rev 13: 873-879, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rijnink EC, Teng YK, Kraaij T, Wolterbeek R, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM. Idiopathic non-lupus full-house nephropathy is associated with poor renal outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 654-662, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ambruzs JM, Walker PD, Larsen CP. The histopathologic spectrum of kidney biopsies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 265-270, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhagat Singh AK, Jeyaruban AS, Wilson GJ, Ranganathan D. Adalimumab-induced IgA nephropathy. BMJ Case Rep 12: e226442, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huerta A, Bomback AS, Liakopoulos V, et al. Renal-limited ‘lupus-like’ nephritis. Neprol Dial Transplant 27: 2337-2342, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maziad ASA, Torrealba J, Seikaly MG, Hassler JR, Hendricks AR. Renal-limited “lupus-like” nephritis: how much of a lupus? Case Rep Nephrol Dial 7: 43-48, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gianviti A, Barsotti P, Barbera V, Faraggiana T, Rizzoni G. Delayed onset of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with “full-house” nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 13: 683-687, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adu D, Williams DG, Taube D, Vilches AR, Turner DR, Cameron JS, Ogg CS. Late onset systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus-like disease in patients with apparent idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Q J Med 52: 471-487, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ruggiero B, Vivarelli M, Gianviti A, et al. Outcome of childhood-onset full-house nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 1194-1204, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sharman A, Furness P, Feehally J. Distinguishing C1q nephropathy from lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1420-1426, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Touzot M, Terrier CS, Faguer S, et al. Proliferative lupus nephritis in the absence of overt systemic lupus erythematosus: a historical study of 12 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e9017, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]