Highlights

-

•

IP3 affinity chromatography column with Plasmodium falciparum infected cells and mass spectrometry were used as an approach to identify IP3 receptors in human malaria parasites.

-

•

Using bioinformatic meta-analyses, we identified potential candidates for IP3-receptor that present binding with IP3 in Plasmodium falciparum.

-

•

Our analyses reveal that PF3D7_0523000, a gene that codes a transport protein associated with multidrug resistance (MDR), is a potential target for IP3.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, IP3 receptor, Malaria, Signaling, MDR transporter

Abstract

Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization induced by second messenger IP3 controls many cellular events in most of the eukaryotic groups. Despite the increasing evidence of IP3-induced Ca2+ in apicomplexan parasites like Plasmodium, responsible for malaria infection, no protein with potential function as an IP3-receptor has been identified. The use of bioinformatic analyses based on previously known sequences of IP3-receptor failed to identify potential IP3-receptor candidates in any Apicomplexa. In this work, we combine the biochemical approach of an IP3 affinity chromatography column with bioinformatic meta-analyses to identify potential vital membrane proteins that present binding with IP3 in Plasmodium falciparum. Our analyses reveal that PF3D7_0523000, a gene that codes a transport protein associated with multidrug resistance as a potential target for IP3. This work provides a new insight for probing potential candidates for IP3-receptor in Apicomplexa.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) is an important second messenger that regulates cytosolic Ca2+ in a variety of Eukaryotic organisms (Michell, 2011; Berridge, 2009). Briefly, the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) mediated by surface receptor breaks phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into soluble short life second messenger IP3 that binds into IP3 receptor (IP3R), culminating in intracellular Ca2+ release (Streb et al., 1983; Berridge and Irvine, 1984).

The phylum Apicomplexa includes unicellular eukaryotes parasites like Plasmodium, the etiology agent of malaria infection, and possesses the metabolic enzymes responsible for generation and degradation of IP3, see review (Garcia et al., 2017). IP3 can mobilize Ca2+from intracellular stores in isolate and permeabilize blood-stage P. chabaudi (Passos and Garcia, 1998) and in intact P. falciparum within red blood cells (RBCs) (Alves et al., 2011). Within RBCs, parasites manage to maintain the Ca2+ stores full even under a low Ca2+environment (Gazarini et al., 2003). An increasing number of reports supporting the existence of intracellular Ca2+release induced by IP3 in malaria parasites (Passos and Garcia, 1998; Alves et al., 2011; Beraldo et al., 2007; Martin et al., 1994; Enomoto et al., 2012; Raabe et al., 2011) suggest the existence of a Ca2+ channel sensitive to IP3, the IP3R.

The IP3R is a well know described protein in vertebrates and contains around four to six transmembrane domains (TMDs), see review (Mikoshiba, 2007). Prole and Taylor (2011) used the sequence of mammal N-terminal IP3R binding domain and the amino-terminal RIH (Ryanodine and IP3R homology) domains to perform a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) on the genome of diverse parasites. However, this work failed to find any potential candidate for IP3R in Apicomplexa. So far, no apicomplexan IP3R candidate has been identified or suggested through bioinformatics approach. Moreover, there is no publication that attempted to use a biochemical approach like an IP3 affinity chromatography column in Apicomplexa to identify proteins that might bind to IP3.

Hirata and collaborators (Hirata et al., 1990) managed to enrich proteins from rat brain sample that has an affinity to IP3, like IP5-phosphatase and IP3 3-kinase using an analogous IP3 affinity chromatography column 2-O-[4-(5-aminoethyl-2-hydroxyphenylazo)benzoyl]−1,4,5-tri-O-phosphono-myo-inositol trisodium salt-Sepharose 4B. Using a similar column, Kishigami and collaborators (Kishigami et al., 2001) managed to identify the PLC protein from octopus’ eyes Todarodes pacificus and reported that squid rhodopsin also has an affinity to IP3. Nevertheless, besides the potential of these columns to enrich proteins that bind to IP3, no IP3R has ever been identified using an IP3-affinity column alone.

By adapting the protocol from Hirata/Kishigami (Hirata et al., 1990; Kishigami et al., 2001), we created a column containing IP3 conjugated with biotin linked with a high-performance sepharose-streptavidin and challenged with proteins from asynchronous P. falciparum blood-stage. Using an IP3-free column containing only sepharose-streptavidin as a reference, we selected only the candidates exclusive on the IP3-column to undergo a series of bioinformatic meta-analyses. Our approach targeted candidates with at least one transmembrane domain, considered essential, conserved among most apicomplexan species, and with unknown or nor-clear function. Finally, the candidate that fit all these criteria were used as targets for in silico molecular docking against IP3.

Using this strategy, we identified the P. falciparum multidrug resistance protein 1 (PfMDR1) as a vital and conserved membrane protein that has the potential to bind to IP3. This protein is located on the parasite food vacuole, a Ca2+ storage compartment (Biagini et al., 2003). Combined, our IP3 affinity column and bioinformatic approach successfully narrow to provide the first small list of malaria proteins candidates with quintessential features expected from an IP3R.

Material and methods

P. falciparum culture

P. falciparum (D37) parasites were maintained in culture as described (Trager and Jensen, 1976). Briefly, P. falciparum were cultured in RPMI media supplemented with 50 mg/L hypoxanthine; 40 mg/L gentamycin; 435 mg/L NaHCO3; 2% hematocrit of A+ human red blood cells and 10% A+human blood serum in an atmosphere of 5% CO2; 3% O2; 92% N2 at 37 °C. Media was changed every 24 h and RBCs replaced every 48 h. Parasitemia and the development stage of cultures were determined by Giemsa-stained smears.

P. falciparum protein sample

Total P. falciparum protein extract was obtained from 2.5 L of unsynchronized culture, at 8% parasitemia. The culture was washed three times in PBS (300 g, 5 min) and parasites isolated from erythrocytes using 0.03% (w/v) saponin (Sigma) on PBS containing protease inhibitors: antiplaque, pepstatin, chymostatin, and leupeptin (Sigma) at concentrations of 20 μg/mL each and 500 μM benzamidine (Sigma). Isolate parasites were centrifuge on 1300 g for 10 min at 4 °C and washed three times in PBS with protease inhibitors. The isolate parasite samples were resuspended in 50 mM TRIS-HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors, and 1 mM PMSF. Samples were sonicated on SONIC (Vibracell) 50% potency for 20 s for 3 times on ice (10 s interval between each sonication) follow by a 1300 g centrifugation for 10 min at 4 °C for removal of the insoluble pellet. DNAse and RNAse (final concentration 200 ng/μL each) were added on soluble pellet and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. The samples were passed through a 0.45 μm filter. The amount of protein was quantitated using Pierce's BCA protein assay kit.

IP3-affinity chromatography column

For the column, it was used a commercial high performance Sepharose substrate bound to streptavidin (GE Healthacare Life Science) and biotin-conjugated IP3 (Echelom Biosciences). The streptavidin-sepharose column was equilibrated by washing once with 10x volume of ice-cold, 0.45 μm filter binding buffer (20 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM LiCl and 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). The columns were mounted in a 15 mL sterile falcon tube. For each column it was used 1.25 ml of equilibrated Sepharose-streptavidin resuspended in binding buffer mixed with 20 μg of IP3-biotin. The columns were left by constant stirring for 12 h at 4 °C in a dark environment and then centrifuged for 1 min, 300 g at 4 °C. The supernatant containing excess IP3-biotin was removed and columns were washed five times with 2 ml of ice-cold binding buffer to remove any free IP3-biotin. Two distinct columns were assembled: one containing IP3-biotin-sepharose-streptavidin and other containing only sepharose-streptavidin. In each column was loaded with 2.5 mg of P. falciparum protein extract and the volume was adjusted with ice-cold binding buffer with protease inhibitors until a final volume of 5 ml. The columns were incubated at 4 °C under gentle, steady shaking in a light-protected environment for 12 h and finally centrifuged for 1 min at 300 g at 4 °C to discard the supernatant. Each column was washed seven times with ice-bound binding buffer with protease inhibitors. To elute the proteins, 1 mL of an ice-cold elution buffer (8 M Guanidin-HCl, 20 mM LiCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH: 1.5 with protease inhibitors) was added on each column followed by constant stirring for 1 h at 4 °C. At the end of incubation, the columns were centrifuged for 1 min at 300 g, and the supernatant was collected in sterile low binding protein Eppendorf.

Mass spectrometry

The protein samples were applied on 8% polyacrylamide gel and run at low voltage (60 v) until the bands were discriminated. After the run, the gel was fixed and stained following the recommendations of the "Colloidal Blue Staining Kit" from Invitrogen. The gel sections containing visible bands were cut and sent for analysis on a mass spectrometer at Taplin Mass Spectrometry, Harvard Medical School (https://taplin.med.harvard.edu/) for protein identification. All identified proteins containing at least one exclusive peptide match were considered for analyses.

Transmembrane domain prediction

To detect a transmembrane domain's presence, the whole amino acid sequence from the protein identified at mass spectrometry was analysed using the public HMMTOP program version 2.0 (www enzim.hu/hmmtop/). This program predicts the number of transmembrane helicases and their position from the peptide/protein amino acid sequence.

Phenotype score, conservation, and function predictions

The phenotype score used the determinate gene essentiality of each candidate was obtained from the work of Zhang et al. (2018) available on PlasmoDB (https://plasmodb.org/plasmo). To identify orthologs candidates among the Apicomplexa group, we use the OrthoMCL database (https://orthomcl.org/orthomcl). For function prediction, we consulted the gene annotation information provided by PlasmoDB.

In silico docking with IP3

The primary sequence of MDR1 (Gene - PF3D7_0523000, plasmodb.org) was used to build its probable 3D structure by homology modeling. The server SwissModel (Schwede et al., 2003) was employed to automatically create the models optimized to bind IP3 at various locations inside MDR1 homology. Blind molecular docking simulations were carried out to obtain possible interactions for the intermembrane domain as predicted by the TMHMM Server (Krogh et al., 2001). The SwissDock (Grosdidier et al., 2011) server enabled the study of IP3 intermembrane MDR1 domain binding poses. Additionally, the IP3-Ion-MDR1 binding was further investigated using the multidrug transporter permeability (P)-glycoprotein is adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (PDB id: 6C0V). The later ability to bind simultaneously ATP and a divalent cation at the intracellular domain was used to guide the inspect a hypothetical IP3-Ion-MDR1 interaction. IP3 was manually positioned inside the ATP cavity to mimic an IP3-Mg2+ interaction. The binding conformation was optimized with molecular mechanics employing the UCSF (Pettersen et al., 2004) chimera minimize structure tools.

Protein-protein interaction network

Using Plasmodium interactome data (Hillier et al., 2019), we looked for the proteins that interact with the MDR1. The protein annotation and functions were also retrieved from the original publication. The network was generated using Cytoscape (Shannon et al., 2003).

Results

IP3-affinity chromatography data

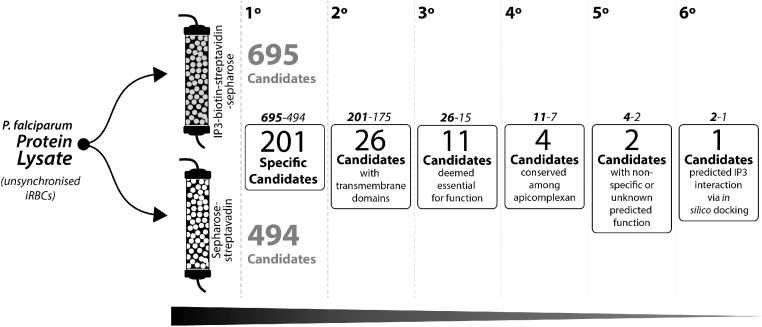

Adapting the protocol based on Hirata/Mishigami (Hirata et al., 1990; Kishigami et al., 2001), we use an IP3 affinity chromatography column with protein homogenate from unsynchronized asexual blood stages of isolated P. falciparum as the first step to identified potential proteins that have a similar function to IP3R receptor in a mammal (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic approached to pinpoint potential candidates for IP3R from isolates blood stage P. falciparum. 1° step: selection of proteins that are exclusively found on IP3-Biotin-streptavidin-sepharose column. 2° step: selection of proteins that contains at least one transmembrane domain. 3° step: selection of protein that are considered essential for malaria parasite during red blood stage development. 4° step: Selection of proteins that are conserve among most species within Apicomplexa group. 5° step: selection of protein with unknow or non-specific metabolic function. 6° step: candidates with positive in-silico docking against IP3.

The access code of the brute data on mass spectrometry analyses from the eluate samples of the IP3-affinity chromatography column can be found in Supplemental Material Table 1. At least 695 proteins from P. falciparum containing at least one exclusive peptide were detected from the IP3-sepharose column. In comparison, 494 proteins were detected from the sepharose matrix alone (Fig. 1). All proteins exclusively present on IP3-sepharose were selected (total 201 proteins) for the bioinformatic meta-analyses (Sup. Table 2).

Once the proteins exclusive for IP3-column were identified (Sup. Table 2), the first bioinformatic approach aimed to select proteins that contain at least one transmembrane domain (TMD). The TMD is an important structure to anchor proteins through biological membranes by its physical properties like the length and hydrophilicity of the transmembrane span (Cosson et al., 2013), every IP3R in vertebrates, invertebrates and single eukaryotes organism possess a TMDs, so we used this feature as the second step to select potential candidates for IP3R. Fig. 1.

Table 1 summarizes 26 proteins exclusively found at IP3-biotin-streptavidin-sepharose column containing at least one TMDs. Transfection of P. falciparum to constitutively express IP3-sponge, a protein containing a modified IP3 binding domain based on mouse IP3R that sequestrates cytosolic IP3 (Usui-Aoki et al., 2005), did not result in viable parasites (Pecenin et al., 2018), suggesting a vital role of IP3 signaling in P. falciparum. Accordingly, the next step to narrow the number of potential candidates that might act as IP3R in malaria is to focus on essential genes. To deem whether a gene is essential, we considered only the candidates that scored lower than 0.5 on its mutagenic index of phenotype graphic (data provided by PlasmoDB). That decreases the number of candidates to 11 (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Table 1.

The table I: The list of 26 proteins exclusively found at IP3-biotin-streptavidin-sepharose column that contains at least one TMDs.

| Gene code (PlasmoDB) | Predicted function/ annotation | Number TMDs | Essential gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| PF3D7_1001500 | Early transcribed membrane protein 10.1 | 2 | Yes |

| PF3D7_0501300 | Skeleton-binding protein 1 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_1133400 | Apical membrane antigen 1 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0827900 | Protein disulfide-isomerase | 1 | Yes |

| PF3D7_0918000 | Glideosome-associated protein 50 | 2 | No |

| PF3D7_1364100 | 6-cysteine protein P92 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0523000 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 | 11 | Yes |

| PF3D7_0202500 | Early transcribed membrane protein 2 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0817500 | Histidine triad nucleotide-binding protein 1 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0402100 | Plasmodium exported protein (PHISTb), unknown function | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0501200 | Parasite-infected erythrocyte surface protein | 3 | No |

| PF3D7_0501100 | Heat shock protein 40, type II | 1 | yes |

| PF3D7_1252100 | Rhoptry neck protein 3 | 3 | Yes |

| PF3D7_1237700 | Conserved protein, unknown function | 5 | Yes |

| PF3D7_0801800 | Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase, putative | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0731300 | Plasmodium exported protein (PHISTb), unknown function | 1 | Yes |

| PF3D7_0702500 | Plasmodium exported protein, unknown function | 2 | No |

| PF3D7_1344800 | Aspartate carbamoyltransferase | 1 | Yes |

| PF3D7_1332600 | DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase 1 | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_1105300 | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknow function | 1 | Yes |

| PF3D7_1038000.1 | Antigen UB05 | 2 | Yes |

| PF3D7_1016900 | Early transcribed membrane protein 10.3 | 2 | No |

| PF3D7_1002100 | EMP1-trafficking protein | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_1476600 | Plasmodium exported protein, unknown function | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_1458100 | Protein PET117, putative | 1 | No |

| PF3D7_0508000 | 6-cysteine protein | 1 | Yes |

There is pharmacological evidence of the IP3R in multiple apicomplexan parasites (Garcia et al., 2017), so in our analyses we considered only conserved genes among multiples species withing the Apicomplexa phylum as the fourth step for candidate screening. Only four essential candidates with TMDs domains met this criterium: multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1); a heat shock protein 40, type II (HSP40); aspartate carbamoyltransferase (ATCase), and antigen UB05. PlasmoDB access code: PF3D7_0523000, PF3D7_0501100, PF3D7_1344800 and PF3D7_1038000 respectively. Among these 4 candidates, only MDR1 and antigen UB05 has unknow or unclear function. The HSP40 is a cochaperone protein with conserved J-domain that regulates other heat socks protein 70 (HSP70) (Walsh et al., 2004), and the ATCase is an enzyme important for the pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway (Simmer et al., 1990). The MDR1 was the only candidate with information available to build a 3D structure by homology modeling to perform an in-silico binding with IP3.

IP3-MRD1 binding modeling and protein interactions network

The MDR1 model provides by the SwissModel server proved to be quite similar to the human P-glycoprotein ABCB1 receptor, protein data bank id: 7A69 (Nosol et al., 2020). The sequence alignment proved that a homology model could be built with fair quality with an identity of 29.7% and similarity of 48.2% (Pairwise Sequence Alignment EMBOSS Water server, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/). Two binding position at the transmembrane domain of MRD1 and IP3 binding was estimated by the SwissDock server (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the SwissDock most energetically favored binding poses of IP3−MDR1. The cytosolic nucleotide-binding domain (upper part) display an IP3 associated with divalent cation (green spheres) interacting on the same ATP binding pocket. The transmembrane domains (lower part) display two possible pocket sites on IP3 interaction and their respective interaction energy values (kcal/mol). On the right side, details of the IP3−MDR1 pocket 1 interaction, a region rich on lysine..

The pocket 1 (binding energy −15.7 kcal/mol) proved to be the best IP3 docking position. The site is a lysin rich domain able to form various hydrogen bonds with IP3. The second-best bind pocket proved to be less favored as derived from the lower interaction energy (−11.4 kcal/mol). Another binding possibility investigated was the interaction with the same pocket ATP binding. The interaction involves the presence of a divalent cation (green spheres) like Mg2+ intercalating with IP3. The MDR1 is an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family member associated with multidrug drug resistance due to translocating amphiphilic compounds (Koenderink et al., 2010). The translocation of a substrate across the membrane by proteins like P. falciparum MDR1 requires an ATP binding on Q-loop site that causes a rearrangement of TM (Jones et al., 2009). The binding on IP3-divalent cation on the MDR1 Q-loop site suggests a potential competition between ATP and IP3. Interestingly, ATP is known to allosterically modulate the functional of mammal IP3R (Ferris et al., 1990; Bezprozvanny and Ehrlich, 1993), including the inhibition of Ca2+flux regulated by IP3R under a high concentration of ATP (Bezprozvanny and Ehrlich, 1993).

To help uncover the cellular function of MDR1 protein, we searched for proteins that interact with MDR1 in the Plasmodium interactome data (Hillier et al., 2019) (Fig. 3). The data suggests that MDR1 interacts with activated C kinase receptors (RACK1, PF3D7_1148000). The PfRACK1 can inhibit host IP3-mediated Ca2+signaling by direct interaction with IP3R (Sartorello et al., 2009). The interaction with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (EIF2, PF3D7_1410600), EIF2β (PF3D7_1010600), EIF2γ (PF3D7_1410600) and serine/threonine protein kinase (PF3D7_1148000) suggests that PfMDR1 can associate or have similar functions to other receptors and nuclear factors that coordinate signaling events regulated by protein kinase.

Fig. 3.

Proteins that interact with MDR1. The network shows the proteins (gray nodes) that interact with MDR1 (red node) according to the Plasmodium interactome data (Hillier et al., 2019). Gene codes: 2270.T00246, translation initiation factor (PF3D7_0607000). SNRPD1, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D1(PF3D7_1125500). ABCE1, ABC transporter E family member 1 (PF3D7_1,368,200). PRP2, pre-mRNA-splicing factor ATP-dependent RNA helicase PRP2 (PF3D7_1231600). PF11_0488, serine/threonine protein kinase (PF3D7_1148000). DDX1, ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 (PF3D7_0521700). SEC13, protein transport protein SEC13 (PF3D7_1230700). SEC24A, transport protein Sec24A (PF3D7_1361100). EIF2GAMMA, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit gamma (PF3D7_1410600). RON6, rhoptry neck protein 6 (PF3D7_0214900). RACK1, receptor for activated C kinase (PF3D7_0826700). MDR2, multidrug resistance protein 2 (PF3D7_11447900). 2270.T00294, ATP-dependent RNA helicase MTR4, (PF3D7_0602100). DBP5, ATP-dependent RNA helicase DBP5 (PF3D7_1459000). SEC12, guanine nucleotide-exchange factor (PF3D7_1116400). WDR26, WD repeat-containing protein 26 (PF3D7_0518600). CBP20, nuclear cap-binding protein subunit 2 (PF3D7_0415500). PRPF19, pre-mRNA-processing factor 19 (PF3D7_0308600). EIF2BETA, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit beta (PF3D7_1010600). 2270.T00096, cleavage stimulation factor subunit 1 (PF3D7_0620500).

Discussion and conclusion

Phylogenetic analyses and comparative genomic data revealed both unique and conserved proteins related to calcium signaling pathways on apicomplexan parasites (Prole and Taylor, 2011; Nagamune and Sibley, 2006; Ladenburger et al., 2009), nevertheless, the IP3R still remains a major missing piece of this Ca2+signaling toolkit. Studies using exogenous IP3 on malaria parasites support the existence of protein sensitive to IP3 that is capable to trigger a Ca2+ response (Passos and Garcia, 1998; Alves et al., 2011). The constant failed to identify this protein in Apicomplexa suggests this group has a distinct and unique structure compared to the IP3-binding core domain from other eukaryotes. The search for an IP3R in Apicomplexa requires a different strategy that does not rely exclusively on bioinformatics tools as BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) based on previously known IP3R.

The use of IP3 affinity chromatography column has been successfully reported to concentrate proteins that interact with high affinity to IP3 analogues (Hirata et al., 1990) and retained key components from IP3—Ca2+ signaling from proteins extract from tissues (Kishigami et al., 2001). In this work, we used a biotin-inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate attached to a high-performance streptavidin-sepharose substrate to initially enriching proteins with IP3 affinity from unsynchronized isolate P. falciparum blood culture. One of the significant limitations of using chromatography affinity column based on a short life IP3 molecule is the number of naturally present proteins at sample homogenate that degrade this second messenger. P. falciparum contains proteins that can dephosphorylate or phosphorylate IP3 like inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase (Gardner et al., 2002). In this protocol, we tried to overcome this limitation by keeping all the binding and elution steps under low temperature while adding LiCl in every buffer. LiCl has been previously used to inhibit the dephosphorylation of IP3 (Elabbadi et al., 1994; Irvine et al., 1985; Thomas et al., 1984). Another risk of using an IP3 affinity column assumes that protein(s) that might interact with IP3 in Plasmodium do not bind/interact with strong affinity with the sepharose-streptavidin substrate alone. We excluded all 494 proteins that bind with the sepharose-free IP3 column as a potential IP3R candidate (Fig. 1).

From the 201 proteins identified exclusively from the IP3-sepharose column, 175 did not contain any TMDs suggesting the protocol used to extract the proteins from parasite lysate benefited mostly soluble proteins that do not strongly interact with lipid bilayers. This protocol can be optimized for future trials by using a protein extraction that targets membrane proteins (MPs). The IP3R in mammals is an MP protein containing 6 TMDs (Joseph, 1996). The presence of TMDs is an essential aspect of any MPs to physically interact with biological membranes (Cosson et al., 2013). It is fair to predict that any protein with the potential function of IP3R should have TMDs to interact with membranes. Table 1 list all candidates with TMDs exclusively from IP3-column.

Ca2+is a second messenger that regulates a variety of vital functions in apicomplexan parasites (Nagamune and Sibley, 2006; Docampo et al., 2014; Budu and Garcia, 2012). Accordingly, the use of 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borinate (2-APB), a pharmacological drug that inhibits IP3R, abolished spontaneous Ca2+mobilization and compromise intracellular development of blood stage P. falciparum (Enomoto et al., 2012). Pecenin and collaborator (Pecenin et al., 2018) failed to obtain any viable parasite expressing IP3-sponge. These data suggest that the IP3—Ca2+ signaling pathway has a vital role during intraerythrocytic development of P. falciparum and support our hypotheses that a potential candidate for IP3R in Plasmodium not only has to present a TMDs, but also has to be essential. A prediction of gene essentiality in P. falciparum, based on the work of Zhang and collaborators (Zhang et al., 2018) is available for consultation at the PlasmoDB website.

The pharmacological evidence that supports the IP3—Ca2+ signaling pathway in the Apicomplexa group is not exclusive to malaria parasites but also present in Toxoplasma gondii (Lourido and Moreno, 2015; Chini et al., 2005; Lovett et al., 2002) and Babesia bovis (Florin-Christensen et al., 2000). The strategy to pinpoint the potential candidate for IP3R in apicomplexan should not rely on gene only exclusive to Plasmodium species. Adding this extra meta-analysis step, the list of potential candidates presented exclusively on the IP3-sepharose column is finally reduced to four proteins: a MDR1; HSP40; an ATCase, and antigen UB05. Among those four, only MDR1 and antigen UB05 currently have an undefined function.

The small number of candidates makes the use of more computational demanding bioinformatic analyses more feasible. A molecular docking allows us to target the structural protein complexes from our candidate list against potential ligand as IP3 or other potent IP3-analogues drugs like adenophostin A (Mak et al., 2001).

Molecular docking on IP3 on P. falciparum MDR1 protein revealed two potential binding sites on TMD: pocket site 1 (binding energy −15.7 kcal/mol) and pocket site 2 (−11.4 kcal/mol), see Fig. 2. This data suggests that MDR1 pocket 1 has a higher affinity to IP3 compared to IP3-binding core of mammal IP3R (ΔG = −10.3 kcal/mol on 23 °C) (Ding et al., 2010) and a lower affinity when compare to IP3-binding with N-terminal region of mammal IP3R (ΔG = −79.5 kcal/mol) (Chandran et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the binding of ATP on Q-Loop site on the nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) likely causes profound changes in the TMD region (Jones et al., 2009), making it hard to predict the actual affinity of the MDR1 protein with IP3.

In P. falciparum, the MDR1 gene encodes for a 162.2 kg Daltons P-glycoprotein located on the digestive vacuole (DV) (Cowman et al., 1991) with unclear function. Still, the polymorphisms within this protein are associated with increases in vitro resistance against multiple antimalarial drugs like quinine (Sidhu et al., 2002; Sidhu et al., 2006; Sanchez et al., 2008; Basco et al., 1995; Reed et al., 2000; Cowman et al., 1994; Duraisingh et al., 2000; Price et al., 2004). The MDR1 displays a role as a transporter protein that brings solutes into DV. It consists of two distinct homologous regions: one cytosolic nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and a substrate-binding consisting of 11 TMDs (Friedrich et al., 2014; Rohrbach et al., 2006). Interestingly, in malaria parasites, the DV is an acid compartment known to be a dynamic intracellular Ca2+store (Biagini et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 1998; Borges-Pereira et al., 2020; Varotti et al., 2003), making the subcellular location of MDR1 protein suitable for an IP3R-like candidate. Moreover, the in vivo and in vitro treatment with IP3R inhibitor 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borinate (2-APB) is associated with reversing resistance to antimalarial chloroquine in P. falciparum and P. chabaudi parasites, presumably by disrupting Ca2+homeostasis (Mossaad et al., 2015). Multiple antimalarial drugs can also disrupt the Ca2+ dynamic on the parasite (Lee et al., 2018; Gazarini et al., 2007), nevertheless, there is no direct evidence that suggests the MDR1 acts as a Ca2+ gate.

The lack of information to build a quality 3D model for in-silico analyses on UB05, HSP40 and ATCase candidates does not exclude them as a potential role in sensing IP3. The next natural step is to obtain functional evidence that these four candidates act as a protein sensitive to IP3. One suggestion is expressing them on a triple IP3R knock-out cell lines like DT40 chicken B cell (Winding and Berchtold, 2001) and test its sensitivity to mobilize Ca2+ with IP3.

Considering that agents that disrupt IP3R channels such as 2-APB block malaria in vitro growth (Beraldo et al., 2007; Enomoto et al., 2012; Pecenin et al., 2018), identify this receptor in Plasmodium will not only add crucial missing information on malaria Ca2+ signaling, but it will also present a potential new target for pharmacological treatment. This work aims to stimulate the use of IP3-affinity column with bioinformatic strategies as a potential tool to identify proteins that might act as IP3R in Apicomplexa. The MDR1 seems to be a promising candidate waiting to be validated. Nevertheless, this is just an initial but an important first step from a long rewarding task of finding the Apicomplexa channel sensitive to IP3.

Funding

Celia R. S. Garcia is funded by FAPESP (2017/08684–7; 2018/07177–7). Helder Nakaya is funded by FAPESP2018/14933–2.

Author contribution

All authors have contributed to discuss experimental design, discussing the data and manuscript writing. EA; EG and HN performed experiments.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of financial or commercial interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr Akio Kishigami for the helpful suggestion on the IP3-Affinity Column. Ross Tomaino from Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility for helpful support on mass spectrometry data. Colsan (Associação Beneficente de Coleta de Sangue) for providing the human blood and plasma used on parasite culture.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crmicr.2022.100179.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alves E., Bartlett P.J., Garcia C.R., Thomas A.P. Melatonin and IP3-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum within infected red blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(7):5905–5912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco L.K., Le Bras J., Rhoades Z., Wilson C.M. Analysis of pfmdr1 and drug susceptibility in fresh isolates of Plasmodium falciparum from sub-Saharan Africa. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1995;74(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)02492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraldo F.H., Mikoshiba K., Garcia C.R. Human malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, displays capacitative calcium entry: 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate blocks the signal transduction pathway of melatonin action on the P. falciparum cell cycle. J. Pineal Res. 2007;43(4):360–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793(6):933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J., Irvine R.F. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature. 1984;312(5992):315–321. doi: 10.1038/312315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I., Ehrlich B.E. ATP modulates the function of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-gated channels at two sites. Neuron. 1993;10(6):1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagini G.A., Bray P.G., Spiller D.G., White M.R., Ward S.A. The digestive food vacuole of the malaria parasite is a dynamic intracellular Ca2+ store. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(30):27910–27915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Pereira L., Thomas S.J., Dos Anjos E.S.A.L., Bartlett P.J., Thomas A.P., Garcia C.R.S. The genetic Ca(2+) sensor GCaMP3 reveals multiple Ca(2+) stores differentially coupled to Ca(2+) entry in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(44):14998–15012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budu A., Garcia C.R. Generation of second messengers in Plasmodium. Microbes Infect. 2012;14(10):787–795. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran A., Chee X., Prole D.L., Rahman T. Exploration of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) regulated dynamics of N-terminal domain of IP3 receptor reveals early phase molecular events during receptor activation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):2454. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39301-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini E.N., Nagamune K., Wetzel D.M., Sibley L.D. Evidence that the cADPR signalling pathway controls calcium-mediated microneme secretion in Toxoplasma gondii. Biochem. J. 2005;389(2):269–277. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041971. Pt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson P., Perrin J., Bonifacino J.S. Anchors aweigh: protein localization and transport mediated by transmembrane domains. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23(10):511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowman A.F., Galatis D., Thompson J.K. Selection for mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is linked to amplification of the pfmdr1 gene and cross-resistance to halofantrine and quinine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91(3):1143–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowman A.F., Karcz S., Galatis D., Culvenor J.G. A P-glycoprotein homologue of Plasmodium falciparum is localized on the digestive vacuole. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113(5):1033–1042. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Rossi A.M., Riley A.M., Rahman T., Potter B.V., Taylor C.W. Binding of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and adenophostin A to the N-terminal region of the IP3 receptor: thermodynamic analysis using fluorescence polarization with a novel IP3 receptor ligand. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77(6):995–1004. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R., Moreno S.N., Plattner H. Intracellular calcium channels in protozoa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014;739:4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraisingh M.T., Jones P., Sambou I., von Seidlein L., Pinder M., Warhurst D.C. The tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with increased sensitivity to the anti-malarials mefloquine and artemisinin. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;108(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elabbadi N., Ancelin M.L., Vial H.J. Characterization of phosphatidylinositol synthase and evidence of a polyphosphoinositide cycle in Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1994;63(2):179–192. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto M., Kawazu S., Kawai S., Furuyama W., Ikegami T., Watanabe J., et al. Blockage of spontaneous Ca2+ oscillation causes cell death in intraerythrocitic Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e39499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris C.D., Huganir R.L., Snyder S.H. Calcium flux mediated by purified inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in reconstituted lipid vesicles is allosterically regulated by adenine nucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87(6):2147–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin-Christensen J., Suarez C.E., Florin-Christensen M., Hines S.A., McElwain T.F., Palmer G.H. Phosphatidylcholine formation is the predominant lipid biosynthetic event in the hemoparasite Babesia bovis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;106(1):147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich O., Reiling S.J., Wunderlich J., Rohrbach P. Assessment of Plasmodium falciparum PfMDR1 transport rates using Fluo-4. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2014;18(9):1851–1862. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C.R., Ann S.E., Tavares E.S., Dluzewski A.R., Mason W.T., Paiva F.B. Acidic calcium pools in intraerythrocytic malaria parasites. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1998;76(2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(98)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia C.R.S., Alves E., Pereira P.H.S., Bartlett P.J., Thomas A.P., Mikoshiba K., et al. InsP3 signaling in apicomplexan parasites. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017;17(19):2158–2165. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170130121042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M.J., Hall N., Fung E., White O., Berriman M., Hyman R.W., et al. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419(6906):498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazarini M.L., Sigolo C.A., Markus R.P., Thomas A.P., Garcia C.R. Antimalarial drugs disrupt ion homeostasis in malarial parasites. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(3):329–334. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazarini M.L., Thomas A.P., Pozzan T., Garcia C.R. Calcium signaling in a low calcium environment: how the intracellular malaria parasite solves the problem. J. Cell. Biol. 2003;161(1):103–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosdidier A., Zoete V., Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W270–W277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier C., Pardo M., Yu L., Bushell E., Sanderson T., Metcalf T., et al. Landscape of the Plasmodium interactome reveals both conserved and species-specific functionality. Cell Rep. 2019;28(6):1635–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.019. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M., Yanaga F., Koga T., Ogasawara T., Watanabe Y., Ozaki S. Stereospecific recognition of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate analogs by the phosphatase, kinase, and binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265(15):8404–8407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine R.F., Anggard E.E., Letcher A.J., Downes C.P. Metabolism of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate in rat parotid glands. Biochem. J. 1985;229(2):505–511. doi: 10.1042/bj2290505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.M., O'Mara M.L., George A.M. ABC transporters: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;34(10):520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S.K. The inositol triphosphate receptor family. Cell Signal. 1996;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(95)02012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishigami A., Ogasawara T., Watanabe Y., Hirata M., Maeda T., Hayashi F., et al. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-binding proteins controlling the phototransduction cascade of invertebrate visual cells. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204(3):487–493. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.3.487. Pt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenderink J.B., Kavishe R.A., Rijpma S.R., Russel F.G. The ABCs of multidrug resistance in malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26(9):440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305(3):567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenburger E.M., Sehring I.M., Korn I., Plattner H. Novel types of Ca2+ release channels participate in the secretory cycle of Paramecium cells. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29(13):3605–3622. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01592-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.H., Dhingra S.K., Lewis I.A., Singh M.K., Siriwardana A., Dalal S., et al. Evidence for regulation of hemoglobin metabolism and intracellular ionic flux by the plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):13578. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31715-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourido S., Moreno S.N. The calcium signaling toolkit of the Apicomplexan parasites Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium spp. Cell Calcium. 2015;57(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett J.L., Marchesini N., Moreno S.N., Sibley L.D. Toxoplasma gondii microneme secretion involves intracellular Ca(2+) release from inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP(3))/ryanodine-sensitive stores. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(29):25870–25876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak D.O., McBride S., Foskett J.K. ATP-dependent adenophostin activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel gating: kinetic implications for the durations of calcium puffs in cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;117(4):299–314. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S.K., Jett M., Schneider I. Correlation of phosphoinositide hydrolysis with exflagellation in the malaria microgametocyte. J. Parasitol. 1994;80(3):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell R.H. Inositol and its derivatives: their evolution and functions. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2011;51(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikoshiba K. IP3 receptor/Ca2+ channel: from discovery to new signaling concepts. J. Neurochem. 2007;102(5):1426–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossaad E., Furuyama W., Enomoto M., Kawai S., Mikoshiba K., Kawazu S. Simultaneous administration of 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate and chloroquine reverses chloroquine resistance in malaria parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59(5):2890–2892. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04805-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamune K., Sibley L.D. Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses of calcium ATPases and calcium-regulated proteins in the apicomplexa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23(8):1613–1627. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosol K., Romane K., Irobalieva R.N., Alam A., Kowal J., Fujita N., et al. Cryo-EM structures reveal distinct mechanisms of inhibition of the human multidrug transporter ABCB1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117(42):26245–26253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010264117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos A.P., Garcia C.R. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate induced Ca2+ release from chloroquine-sensitive and -insensitive intracellular stores in the intraerythrocytic stage of the malaria parasite P. chabaudi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;245(1):155–160. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecenin M.F., Borges-Pereira L., Levano-Garcia J., Budu A., Alves E., Mikoshiba K., et al. Blocking IP3 signal transduction pathways inhibits melatonin-induced Ca(2+) signals and impairs P. falciparum development and proliferation in erythrocytes. Cell Calcium. 2018;72:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., Uhlemann A.C., Brockman A., McGready R., Ashley E., Phaipun L., et al. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet. 2004;364(9432):438–447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16767-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prole D.L., Taylor C.W. Identification of intracellular and plasma membrane calcium channel homologues in pathogenic parasites. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raabe A.C., Wengelnik K., Billker O., Vial H.J. Multiple roles for Plasmodium berghei phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C in regulating gametocyte activation and differentiation. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13(7):955–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed M.B., Saliba K.J., Caruana S.R., Kirk K., Cowman A.F. Pgh1 modulates sensitivity and resistance to multiple antimalarials in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2000;403(6772):906–909. doi: 10.1038/35002615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach P., Sanchez C.P., Hayton K., Friedrich O., Patel J., Sidhu A.B., et al. Genetic linkage of pfmdr1 with food vacuolar solute import in Plasmodium falciparum. EMBO J. 2006;25(13):3000–3011. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C.P., Stein W.D., Lanzer M. Dissecting the components of quinine accumulation in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;67(5):1081–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorello R., Amaya M.J., Nathanson M.H., Garcia C.R. The plasmodium receptor for activated C kinase protein inhibits Ca(2+) signaling in mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;389(4):586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch M.C. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu A.B., Uhlemann A.C., Valderramos S.G., Valderramos J.C., Krishna S., Fidock D.A. Decreasing pfmdr1 copy number in plasmodium falciparum malaria heightens susceptibility to mefloquine, lumefantrine, halofantrine, quinine, and artemisinin. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194(4):528–535. doi: 10.1086/507115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu A.B., Verdier-Pinard D., Fidock D.A. Chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites conferred by pfcrt mutations. Science. 2002;298(5591):210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1074045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer J.P., Kelly R.E., Rinker A.G., Jr., Zimmermann B.H., Scully J.L., Kim H., et al. Mammalian dihydroorotase: nucleotide sequence, peptide sequences, and evolution of the dihydroorotase domain of the multifunctional protein CAD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87(1):174–178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streb H., Irvine R.F., Berridge M.J., Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306(5938):67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A.P., Alexander J., Williamson J.R. Relationship between inositol polyphosphate production and the increase of cytosolic free Ca2+ induced by vasopressin in isolated hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259(9):5574–5584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W., Jensen J.B. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193(4254):673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui-Aoki K., Matsumoto K., Koganezawa M., Kohatsu S., Isono K., Matsubayashi H., et al. Targeted expression of Ip3 sponge and Ip3 dsRNA impaires sugar taste sensation in Drosophila. J. Neurogenet. 2005;19(3–4):123–141. doi: 10.1080/01677060600569713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varotti F.P., Beraldo F.H., Gazarini M.L., Garcia C.R. Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites display a THG-sensitive Ca2+ pool. Cell Calcium. 2003;33(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh P., Bursac D., Law Y.C., Cyr D., Lithgow T. The J-protein family: modulating protein assembly, disassembly and translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(6):567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winding P., Berchtold M.W. The chicken B cell line DT40: a novel tool for gene disruption experiments. J. Immunol. Methods. 2001;29(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Wang C., Otto T.D., Oberstaller J., Liao X., Adapa S.R., et al. Uncovering the essential genes of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum by saturation mutagenesis. Science. 2018;360(6388) doi: 10.1126/science.aap7847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.