Abstract

Introduction

Severely injured patients develop a dysregulated inflammatory state characterized by vascular endothelial permeability which contributes to multiple organ failure. To date, however, the mediators of and mechanisms for this permeability are not well established. Endothelial permeability in other inflammatory states such as sepsis is driven primarily by overactivation of the RhoA GTPase. We hypothesized that tissue injury and shock drive endothelial permeability after trauma by increased RhoA activation leading to break down of endothelial tight and adherens junctions.

Methods

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were grown to confluence while continuous resistance was measured using ECIS Z-theta technology, 10% ex vivo plasma from severely injured trauma patients was added, and resistance measurements continued for 2 hours. Areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated from resistance curves. For GTPase activity analysis, HUVECs were grown to confluence and incubated with 10% trauma plasma for 5 minutes prior to harvesting of cell lysates. Rho and Rac activity were determined using a G-LISA assay. Significance was determined using Mann-Whitney tests or Kruskal-Wallis test and Spearman r was calculated for correlations.

Results

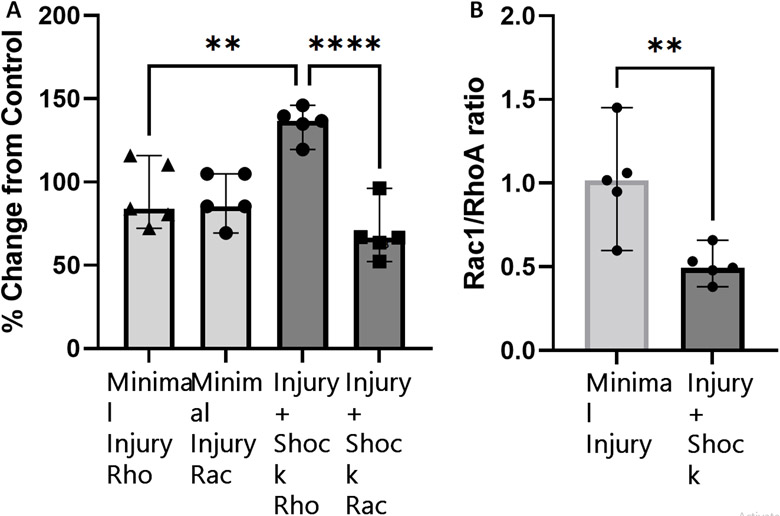

Plasma from severely injured patients induces endothelial permeability with plasma from patients with both severe injury and shock contributing most to this increased permeability. Surprisingly, injury severity (ISS) does not correlate with in vitro trauma-induced permeability (−0.05, p>0.05) while base excess (BE) does correlate with permeability (−.47, p= 0.0001). The combined impact of shock and injury resulted in a significantly smaller AUC in the injury+shock group (ISS>15, BE<−9) compared to the injury only (ISS>15, BE>−9 (p=0.04)) or minimally injured (ISS<15, BE>−9 (p=0.005)) groups. Additionally, incubation with injury+shock plasma resulted in higher RhoA activation (p=0.002) and a trend toward decreased Rac1 activation (p=.07) compared to minimally injured control.

Conclusions

Over the past decade, improved early survival in patients with severe trauma and hemorrhagic shock has led to a renewed focus on the Endotheliopathy of Trauma. This study presents the largest study to date measuring endothelial permeability in vitro using plasma collected from patients after traumatic injury. Here, we demonstrate that plasma from patients who develop shock after severe traumatic injury induces endothelial permeability and increased RhoA activation in vitro. Our ECIS model of trauma-induced permeability using ex vivo plasma has potential as a high throughput screening tool to phenotype endothelial dysfunction, study mediators of trauma-induced permeability, and screen potential interventions.

Keywords: Endotheliopathy, Vascular Permeability, Edema, Traumatic Injury, Shock

Introduction

Trauma remains the leading cause of death under 45 yr of age.[1] A large proportion of trauma patients succumb to initial hemorrhage or traumatic brain injury (TBI) before reaching the hospital,[2] however patients who survive their initial insult are prone to developing a dysregulated proinflammatory state that can lead to multiple organ failure and related mortality.[3] Rapid activation of the innate immune system is well documented early after trauma[4-6] with elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines,[7, 8] DAMPs,[6] and leukocyte activation[8, 9] occurring within the first hour of injury. This proinflammatory state leads to vascular permeability and endothelial activation[4, 7, 10] and contributes to multiple organ failure and increased mortality later in the hospital course.[7, 10]

Much of our current understanding of vascular permeability after trauma is derived from animal models showing increased pulmonary vascular permeability after hemorrhagic shock[11, 12] or surrogate markers of endothelial dysfunction such as glycocalyx shedding.[8, 11] Initial investigation of the effect of ex vivo plasma from patients after trauma on endothelial permeability have shown mixed results[13, 14] and were limited by small samples sizes that precluded analysis of predictors of trauma-induced permeability. Therefore, further studies are required to elucidate the impact of ex vivo trauma plasma on endothelial permeability in an in vitro model. The combination of decreased tissue perfusion and tissue injury severity have been shown to induce coagulopathy,[5, 15] release of DAMPs,[6] and complement activation after trauma,[16] however the underlying mechanisms of postinjury endothelial permeability remain unclear.

Under resting conditions, the vascular endothelium creates a highly selective barrier that regulates the flux of fluids, solutes, proteins, and immune cells.[17] Transport across the endothelium occurs via both transcellular and paracellular routes, however the paracellular route appears to be the driving mechanism of vascular edema in inflammatory states.[18] Paracellular junctions of the vascular endothelium are sealed by tight junctions (TJs), which are composed of claudin and occludin proteins and anchored to the cellular cytoskeleton via zona occluden 1 (ZO-1).[19] VE-cadherin is the primary component of endothelial adherens junctions (AJs) and is important for stabilizing cellular junctions.[20] Endothelial barrier homeostasis is regulated primarily by the small GTPase Rac1 which stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton[21] and increases VE-cadherin density within AJs.[22]

Hemorrhagic shock after trauma causes vascular permeability and subsequent edema,[23] however the mechanisms of these endothelial perturbations remain unclear. Endothelial barrier breakdown in other inflammatory states such as sepsis and anaphylaxis are driven primarily by inactivation of Rac1 and overactivation of RhoA.[20] This decreased Rac1/RhoA ratio drives cytoskeletal rearrangement and actin stress fiber formation.[24] Additionally, phosphorylation and endocytosis of VE-cadherin destabilizes AJs.[20] These enhanced contractile forces and loss of junctional integrity leads to intercellular gap formation and resulting edema.

We sought to investigate the impact of injury severity and decreased tissue perfusion on endothelial barrier integrity after trauma. Additionally, we investigated the role of Rac and Rho GTPases in regulating postinjury permeability. We hypothesized that tissue injury and shock drive endothelial permeability after trauma by increased RhoA activation leading to break down of endothelial TJs and AJs.

Methods

Patients and Sample Collection

Arrival blood samples were collected in citrate anticoagulant from patients meeting criteria for highest-level trauma activation at an urban Level 1 Trauma Center. Patients were excluded if they were <18-year-old, pregnant, incarcerated, or transferred from another hospital. Sample collection and processing have been described in detail previously[25] and proceeded under protocols approved by the institutional review board.

Primary Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) and cultured according to manufacturer provided protocols in Medium 500 with Low Serum Growth Supplements (ThermoFisher). Cells were maintained at 37°C at 5% C02 in a humidified incubator, subcultured once they reached 70% confluence and plated on either 6 well culture plates or ECIS microarray plates as described below.

In Vitro Endothelial Monolayer Resistance and Permeability

HUVECs were seeded in supplemented media (Thermofisher) on a 96 well Electrical Cell Impedance Sensing (ECIS) plate (96w20idf, Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY) which had been washed with 10mM cysteine and coated with 2μg/cm2 type I collagen (Corning, Bedford, MA). ECIS-ZTheta (Applied Biophysics) data collection was started at 4000Hz and 64000Hz as described previously[26, 27] and cells were grown to confluence over 46 hours. Cells were then serum starved for 2hrs in unsupplemented medium 500 (Thermofisher). Ex vivo plasma from injured patients or control was added to each well to a final concentration of 10% by volume and data collection continued for 2 hours. An equivalent volume of unsupplemented media was exchanged as a negative control and thrombin (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) was used as a positive control. Resistance data were normalized across samples to their values at the time of trauma plasma addition. Resistance data was plotted to create permeability curves and areas under the curve (AUC) and lowest points in the resistance curves (lowest point) were calculated using GraphPad Prism Software (San Diego, CA).

Rho and Rac GTPase Activity Assay

HUVECs were seeded in supplemented media in a 6 well tissue culture plate, grown for 24 hours and serum starved in unsupplemented medium 500 for 2 hours. Ex vivo trauma plasma was added to wells and allowed to incubate for 5 minutes. Unsupplemented media was exchanged as the untreated control. Cells were then washed with ice cold PBS and lysate was harvested by scraping in lysis buffer (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) supplemented with protease (Cytoskeleton) and phosphatase (Sigma Aldrich) inhibitor cocktails. Lysate was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Whole lysate protein concentration was calculating using Precision Red reagent (Cytoskeleton) according to manufacturer instructions. GLISA kits (Cytoskeleton) were then used to determine activity levels of Rac1 and RhoA in equalized cell lysates per manufacturer instructions. GTPase activity levels were expressed as a ratio to levels in lysate from untreated control.

Immunoflourescence Microscopy

HUVECs were grown for 48 hours in 4 well chamber slides in supplemented media. After 72 hours media was exchanged for unsupplemented medium 500 and allowed to equilibrate for 1 hour. Cells were then exposed to 10% ex vivo trauma plasma or control for 15 minutes. An equivalent volume of unsupplemented media was used as a negative control and thrombin was used as the positive control. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and permeabilized with 0.3%Triton X100 (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY). ZO-1 (Thermofisher) or VE-Cadherin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) rabbit polyclonal primary antibodies were diluted in PBS with 10% goat serum (Sigma Aldrich) to reduce nonspecific binding, applied to cells, and incubated overnight at 4°C. After this, Alexa Flour goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher) diluted with PBS were applied to the cells for 1 hour at room temperature. Chambers were then removed and ProLong Gold antifade with DAPI (Thermofisher) was applied to each chamber section. Slides were then sealed and allowed to dry. Images were obtained using a Marianas Widefield Inverted Microscope (3i, Denver, CO) and processed using Slidebook 6 software (3i).

Statistical Analysis

Significance was determined using student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA and Mann-Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Correlations were calculated using Pearson’s r or Spearman r as appropriate. All statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism Software.

Results

Patient Population

Permeability tracings were obtained for 54 ex vivo plasma samples which were collected from patients requiring the highest level of trauma activation at an urban Level I Trauma Center. These patients were mostly male (81%) and young (median age 35). They had a median Injury severity score (ISS) of 19, base excess (BE) of −8.2, and 47% sustained penetrating trauma. Table 1 shows demographic and clinical data for patients grouped by ISS and BE. There was no difference between groups in age, gender, initial ED Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) or systolic blood pressure (SBP), penetrating versus blunt mechanism, or percentage of patients who were coagulopathic. Significant differences in ISS and BE were seen between groups as expected. The injury+shock group (ISS>15, BE<−9) required significantly more RBC (6 vs 0, p=0.02), FFP (4 vs 0, p=0.01) and platelet (1 vs 0, p=0.01) transfusions than the minimal injury group (ISS<15, BE>−9) and significantly more platelet transfusions than the injury alone group (ISS>15, BE<−9, 1 vs 0, p=0.03). The injury+shock group also had significantly less hospital-free, ICU-free, and ventilator-free days than the both the minimal injury and shock only (ISS<15, BE<−9) groups. Additionally, the injury alone group has significantly less hospital-free and ICU-free days than the minimal injury group (Table 1). There was 19% mortality in the injury+shock group while none of the other groups included any patient deaths.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data by Group

| Minimally Injured | Shock alone | Injury alone | Shock+Injury | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | ISS<15 BE>−9 | ISS<15 BE<−9 | ISS>15 BE>−9 | ISS>15 BE<−9 | |

| Age | 33 (24, 65) | 33 (31, 46) | 33 (25, 54) | 37 (30, 48) | 0.96 |

| Male | 80% | 90% | 83% | 75% | 0.81 |

| Injury Severity Score | 2.5 (1, 9) | 9.5 (4, 10) | 22 (19, 28) | 25 (22, 33) | <0.0001 |

| GCS | 15 (11, 15) | 15 (13, 15) | 15 (13, 15) | 14 (7.5, 15) | 0.62 |

| ED Systolic Blood Pressure | 133(106, 165) | 115 (87, 128) | 123 (92, 140) | 111 (93, 127) | 0.28 |

| Base Excess | −1.7 (−3, 0.4) | −14 (−22.9, −12.7) | −5 (−7.4, −0.8) | −10.8 (−12.9, −9.8) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathic | 40% | 20% | 24% | 44% | 0.48 |

| Penetrating Mechanism | 33% | 70% | 56% | 31% | 0.15 |

| 24 hour transfusions | |||||

| RBC (u) | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0, 3) | 0.5 (0, 3) | 6 (0, 12.5) | 0.03 |

| Platelets (u) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.5 (0, 2) | 0.005 |

| FFP (u) | 0 (0, 0) | 1 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 2) | 3.5 (0, 8) | 0.02 |

| Clinical Outcomes | |||||

| Hospital LOS | 2 (1, 5) | 5 (4, 10) | 10 (7, 16) | 13 (3, 17) | <0.0001 |

| ICU LOS | 1 (1, 3) | 3 (1, 4) | 4 (3, 6) | 5 (2, 11) | 0.0001 |

| Ventilator days | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 2) | 3 (2, 7) | 0.003 |

| Mortality | 0% | 0% | 0% | 19% | 0.07 |

Endothelial Permeability After Trauma Correlates with Shock

We first examined the impact of injury and shock on endothelial permeability by stratifying patients into shock (BE<−6) or no shock (BE>−6) groups and Injury (ISS>15) or no Injury (ISS<15) groups (Figure 1). Permeability tracings were obtained for individual patient plasma samples in real time using ECIS ZTheta. BE is associated with both decreased AUC (0.47, p= 0.0001) and maximum lowest point (0.28, p= 0.02). However, ISS does not significantly affect AUC (−0.05, p>0.05) or lowest point (−0.12, p>0.05).

Figure 1.

Endothelial permeability after trauma correlates with degree of shock. Permeability tracings were grouped by shock (BE<−6) or Injury (ISS>15) for analysis. Patients in shock(n=26) had significantly more permeability than patients not in shock (n=28), indicated by lower AUC (1b). There was no difference in permeability between patients with (n=33) and without (n=21) injury (Figure 1e-f).

Severe Injury and Shock Combine to Induce Endothelial Permeability After Trauma

We next examined the combined impact of injury and shock on permeability by stratifying patients into 4 groups: minimal injury (ISS<15, BE>−9), shock alone (ISS<15, BE<−9), injury alone (ISS>15, BE>−9), and injury+shock (ISS>15, BE<−9). Figure 2a shows curves averaged by group for all 4 phenotypes. The injury+shock group shows both the largest initial drop in resistance and the slowest recovery to baseline, indicated by a smaller area under the curve (AUC). The shock group showed an initial drop in resistance similar to the minimally injured group but had a slower recovery to baseline which was similar to the injury+shock group. Interestingly, the injury alone group appears more consistent with the minimal injury than the injury+shock curve.

Figure 2.

Injury and shock combine to induce endothelial permeability. To investigate the combined impact of injury and shock, patients were stratified into 4 groups: Minimal Injury (ISS<15, BE>−9; n=10), Shock Alone (ISS<15, BE<−9; n=11), Injury Alone (ISS>15, BE>−9; n=18), and Injury+Shock (ISS>15, BE<−9; n=15). Permeability tracings were averaged for each group. Shock alone induced lower AUC than Minimal Injury but did not reach statistical significance (2b). Injury+Shock induced significantly lower AUC than Minimal Injury or Injury Alone (2b), indicative of significantly more permeability in this group. There was an insignificant trend towards decreased lowest point in the permeability curve induced by the Injury+Shock group but no significant difference in lowest point between the 4 groups (2c).

In our initial analysis using a BE cut off of −6, there was a trend towards lower AUC in patients with high ISS and shock, however there was no significant difference between groups (data not shown). However, due to the linear relationship between BE and both AUC and lowest point, we determined a significant BE cutoff affecting permeability at −9. There was significantly smaller AUC in the injury+shock group compared to the minimal injury (p=0.04) or injury without shock (p=0.005) groups (Figure 2b). There was no difference in AUC demonstrated between minimal injury and injury without shock (figure 2b). There was a trend towards larger initial drop in resistance with increasing shock and injury, with the injury+shock group showing the smallest minimum resistance value; however this did not reach significance (figure 2c).

Injury and Shock Induce RhoA Activation and Decrease the Rac1/RhoA Ratio.

In a preliminary investigation of the mechanisms of trauma-induced permeability, we evaluated the activity of Rho and Rac GTPases in whole cell lysate after incubation with ex vivo plasma from patients after injury. Incubation with injury+shock plasma resulted in significantly higher Rho activation (p=0.002) and a trend toward decreased Rac activation (p=.07) compared to minimally injured control (Figure 3a). After incubation with injury+shock plasma, RhoA GTPase activity increased to 135% of unstimulated control and Rac1 activity decreased to 69% of control. In comparison, incubation with plasma from minimally injured patients resulted in minimal change in Rho and Rac levels (93% and 90% of baseline, respectively). This increase in RhoA activity and depression of Rac1 activity resulted in significantly decreased Rac1/RhoA ratio after incubation with injury+shock plasma compared with minimal injury plasma (0.51 vs 1.01, p=0.008, Figure 3b) which is consistent with increased permeability seen in the injury+shock group. Plasma from patients with injury alone or shock alone did not significantly change RhoA or Rac1 activation compared to minimally injured control (Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Figure 3.

Injury and Shock Induce RhoA Activation and decrease the Rac1/RhoA ratio. Incubation with plasma from patients with Injury+Shock resulted in higher Rho activation (p=0.002) and a trend toward decreased Rac activation (p=0.07) versus minimally injured controls (3a, n=5 in each group). This resulted in a significantly decreased Rac1/RhoA ratio with plasma from patients with Injury+Shock compared with minimal injury controls (0.51 vs 1.01, p=0.008, 3b) which is consistent with increased permeability seen in the Injury+Shock group.

Injury and Shock Induce Endothelial Junctional Breakdown

To visualize the trauma-induced permeability we quantified using ECIS, we used immunofluorescence microscopy to evaluate the impact of ex vivo trauma plasma on junctional proteins. HUVECs were grown to confluence, challenged with 10% ex vivo trauma plasma, and then stained for VE-cadherin or ZO-1. An equivalent volume of unsupplemented media was exchanged for the untreated control. In the VE-cadherin-stained control AJs are clearly visualized in between cells (Figure 4c). After trauma plasma incubation, intracellular gaps form and VE-cadherin staining is decreased at cellular borders, indicating breakdown of AJs (Figure 4d). A similar effect is seen with ZO-1. In the untreated control, ZO-1 is localized to cellular barriers where it anchors the TJs (Figure 4a). After trauma plasma incubation, intracellular gaps form and decreased ZO-1 staining at cellular borders is seen (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Injury and Shock Induce Endothelial Junctional Breakdown. Immunofluorescence microscopy with staining for ZO-1 or VE-Cadherin was utilized to visualize the impact of ex vivo trauma plasma on junctional proteins. In the untreated controls, TJs and AJs are clearly visualized in between cells (orange ovals, Figure 4a,c). After trauma plasma incubation, intracellular gaps form and ZO-1 (figure 4b) and VE-cadherin (Figure 4d) staining is decreased at cellular borders, indicating breakdown of AJs (yellow arrows).

Discussion

Over the past decade, improvements in trauma resuscitation, surgical bleeding control, and correction of coagulopathy have led to improved early survival in patients with severe trauma, however, despite this early survival patients continue to have inflammatory and infectious complications resulting in poor outcomes. This has led to a renewed focus on the Endotheliopathy of Trauma (EOT) and its contribution to multiple organ failure (MOF) and mortality. However, limited data is available examining endothelial permeability specifically in human plasma samples.

This study presents the largest study to date measuring endothelial permeability in vitro using plasma collected from patients after injury. We found that plasma from severely injured patient increases endothelial permeability in vitro. This is consistent with the work of van Leeuwen et. al. who found that plasma from patients after severe trauma and hemorrhagic shock increases endothelial permeability in vitro[14], however their analysis was limited by small sample size which precluded analysis of predictors of trauma-induced permeability.

We found that the increase in endothelial permeability after trauma correlates with BE as a marker of tissue hypoperfusion. Interestingly, permeability did not seem to be independently affected by injury severity. However, when we looked at the combined effect of BE and ISS, only the Injury+Shock group induced more permeability than the injury alone or minimally injured groups (Figure 2). This suggests that tissue injury, which activates the clotting cascade and releases thrombin, and hypoperfusion, which potentiates the release of DAMPs and activation of complement,[5] combine to produce permeability and edema not seen with shock or injury alone. Patients with high injury severity but not shock had significantly higher AUC than patients with both injury and shock, and the injury alone permeability curves were closer to the minimal injury group than the Injury+Shock group (Figure 2). This is consistent with Rahbar et al who found that plasma from trauma patients with normal colloid oncotic pressure increased endothelial resistance compared to healthy controls.[13] There was a trend towards increased permeability in patients with shock but low ISS, which may indicate that a lower injury threshold is sufficient to prime the system to induce inflammation and permeability when combined with tissue hypoperfusion.

The Injury+Shock group had the worst clinical outcomes and showed the most endothelial permeability of all four groups analyzed. This group had fewer hospital-free, ICU-free, and ventilator-free days than the minimal injury and shock only groups, and the worst overall mortality (Table 1). That permeability seen with Injury+Shock is greater than that with injury or shock alone may be an accelerated process similar to the “two-hit” hypothesis of post-injury multiple organ failure where patients have inflammatory priming after injury, and a “second hit” of hemorrhage or infection results in progression to multiple organ failure that is not provoked by either insult alone.[3] Markers of early injury severity such as lactate, BE, or ISS are imperfect as prognostic indicators, and ISS is not calculated in real time. Although more study is required to further elucidate the link between permeability and clinical outcomes, this study indicates that permeability may give us a better idea of prognosis early after injury and our group has ongoing research to investigate the hypothesis that permeability is a better predictor of clinical outcomes than ISS and BE.

Here we also show for the first time that increased permeability after trauma is driven by a decreased Rac1/RhoA ratio and associated with loss of junctional integrity. This is consistent with other inflammatory disease states[20] indicating that the dysregulated inflammatory state and resultant shock after trauma drives permeability. Thrombin is a well-known stimulant of endothelial permeability and has been implicated as a mediator of trauma-induced permeability.[28] Accelerated thrombin generation does occur after injury and levels correlate with injury severity.[29] Although thrombin may play some role in endothelial permeability after trauma, thrombin generation alone does not explain the link between permeability and tissue hypoperfusion or the lack of endothelial permeability in patients with injury but not shock. Indeed, a milieu of proinflammatory mediators have been identified after trauma which could all induce endothelial permeability, and trauma-induced permeability is likely multifactorial.[4, 7] Ongoing research is underway to elucidate the mechanisms, effectors, and interventions for trauma-induced permeability.

Despite ongoing research, few interventions have been developed to target EOT. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) has been shown to stabilize the endothelial barrier,[12, 30] and plasma-based resuscitation after trauma improves patient outcomes.[31, 32] However, many of these studies have relied on artificial stimulants to simulate trauma-induced permeability, or are based on animal models of hemorrhagic shock. Our ECIS model of trauma-induced permeability using ex vivo plasma has potential as a high throughput screening tool to phenotype endothelial dysfunction, study mediators of trauma-induced permeability and screen potential therapeutics targeting EOT.

In conclusion, ECIS allows us to quantify endotheliopathy in our patients by directly measuring vascular endothelial permeability. Although shock seems to drive this permeability, the combination of Injury+Shock was required to induce significantly more permeability than minimal injury alone. Vascular endothelial permeability after trauma is driven by a decreased Rac/Rho ratio, which is important as these GTPases are pharmalogically modifiable, and ECIS can be used as a high-throughput screening tool in the initial pre-clinical testing of potential interventions to balance the Rac/Rho ratio and restore the endothelial barrier.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Phenotyping Rho and Rac activation after trauma. Incubation with plasma from patients with injury+Shock resulted in the highest Rho activation (A) and lowest Rac activation (B), although these results were not statistically significant. Shock alone induced an increase in both Rho and Rac activation, while incubation with injury only plasma resulted in minimal change in Rac or Rho activation from control. Injury+shock plasma induced a decreased Rac/Rho ratio compared to minimal injury (C), but there was no significant difference between shock alone or injury alone groups and any of the other phenotypes.

Funding Disclosure and Conflict of Interest Statement:

The Trauma Research Center has received extramural funding since its inception, mainly from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH, Bethesda, MD, in the form of program project grants. Other important funded research programs include the Control of Major Bleeding after Trauma (COMBAT W81XWH-12-2-2008), which was funded by the Department of Defense; a research grant from the Foundation for Women and Girls with Bleeding Disorders (FWGBD); and a series of grants through the Trans-agency Research Consortium for Trauma Induced Coagulopathy (TACTIC UM1-HL120877) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, NIH. The current major funding source is an RM-1 grant 1RM1GM131968-01 that runs through May of 2024. We otherwise report no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, N. C. f. I. P. a. C., Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2020.

- 2.Kauvar DS; Lefering R; Wade CE, Impact of hemorrhage on trauma outcome: an overview of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and therapeutic considerations. J Trauma, 60 (6 Suppl), S3–11. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauaia A; Moore FA; Moore EE, Postinjury Inflammation and Organ Dysfunction. Crit Care Clin, 33 (1), 167–191. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber-Lang M; Lambris JD; Ward PA, Innate immune responses to trauma. Nat Immunol, 19 (4), 327–341. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kornblith LZ; Moore HB; Cohen MJ, Trauma-induced coagulopathy: The past, present, and future. J Thromb Haemost, 17 (6), 852–862. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MJ; Brohi K; Calfee CS; Rahn P; Chesebro BB; Christiaans SC; Carles M; Howard M; Pittet JF, Early release of high mobility group box nuclear protein 1 after severe trauma in humans: role of injury severity and tissue hypoperfusion. Crit Care, 13 (6), R174. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namas RA; Vodovotz Y; Almahmoud K; Abdul-Malak O; Zaaqoq A; Namas R; Mi Q; Barclay D; Zuckerbraun B; Peitzman AB; et al. , Temporal Patterns of Circulating Inflammation Biomarker Networks Differentiate Susceptibility to Nosocomial Infection Following Blunt Trauma in Humans. Ann Surg, 263 (1), 191–8. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuma M; Canestrini S; Alwahab Z; Marshall J, Trauma and Endothelial Glycocalyx: The Microcirculation Helmet? Shock, 46 (4), 352–7. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson J; Cole E; De'Ath HD; Vulliamy P; Meier U; Pennington D; Brohi K, Early changes within the lymphocyte population are associated with the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in trauma patients. Crit Care, 20 (1), 176. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naumann DN; Hazeldine J; Davies DJ; Bishop J; Midwinter MJ; Belli A; Harrison P; Lord JM, Endotheliopathy of Trauma is an on-Scene Phenomenon, and is Associated with Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome: A Prospective Observational Study. Shock, 49 (4), 420–428. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu F; Peng Z; Park PW; Kozar RA, Loss of Syndecan-1 Abrogates the Pulmonary Protective Phenotype Induced by Plasma After Hemorrhagic Shock. Shock, 48 (3), 340–345. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pati S; Peng Z; Wataha K; Miyazawa B; Potter DR; Kozar RA, Lyophilized plasma attenuates vascular permeability, inflammation and lung injury in hemorrhagic shock. PLoS One, 13 (2), e0192363. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahbar E; Cardenas JC; Baimukanova G; Usadi B; Bruhn R; Pati S; Ostrowski SR; Johansson PI; Holcomb JB; Wade CE, Endothelial glycocalyx shedding and vascular permeability in severely injured trauma patients. J Transl Med, 13, 117. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Leeuwen ALI; Naumann DN; Dekker NAM; Hordijk PL; Hutchings SD; Boer C; van den Brom CE, In vitro endothelial hyperpermeability occurs early following traumatic hemorrhagic shock. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc, 75 (2), 121–133. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen MJ; Kutcher M; Redick B; Nelson M; Call M; Knudson MM; Schreiber MA; Bulger EM; Muskat P; Alarcon LH; et al. , Clinical and mechanistic drivers of acute traumatic coagulopathy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 75 (1 Suppl 1), S40–7. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganter MT; Brohi K; Cohen MJ; Shaffer LA; Walsh MC; Stahl GL; Pittet JF, Role of the alternative pathway in the early complement activation following major trauma. Shock, 28 (1), 29–34. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukriti S; Tauseef M; Yazbeck P; Mehta D, Mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Pulm Circ, 4 (4), 535–51. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan CY; Zhang J; Wu HL; Li T; Liu LM, Regulatory mechanisms, prophylaxis and treatment of vascular leakage following severe trauma and shock. Mil Med Res, 4, 11. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazzoni G; Dejana E, Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol Rev, 84 (3), 869–901. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radeva MY; Waschke J, Mind the gap: mechanisms regulating the endothelial barrier. Acta Physiol (Oxf), 222 (1). 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waschke J; Baumgartner W; Adamson RH; Zeng M; Aktories K; Barth H; Wilde C; Curry FE; Drenckhahn D, Requirement of Rac activity for maintenance of capillary endothelial barrier properties. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 286 (1), H394–401. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daneshjou N; Sieracki N; van Nieuw Amerongen GP; Conway DE; Schwartz MA; Komarova YA; Malik AB, Rac1 functions as a reversible tension modulator to stabilize VE-cadherin trans-interaction. J Cell Biol, 209 (1), 181. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchings SD; Naumann DN; Hopkins P; Mellis C; Riozzi P; Sartini S; Mamuza J; Harris T; Midwinter MJ; Wendon J, Microcirculatory Impairment Is Associated With Multiple Organ Dysfunction Following Traumatic Hemorrhagic Shock: The MICROSHOCK Study. Crit Care Med, 46 (9), e889–e896. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finigan JH; Dudek SM; Singleton PA; Chiang ET; Jacobson JR; Camp SM; Ye SQ; Garcia JG, Activated protein C mediates novel lung endothelial barrier enhancement: role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor transactivation. J Biol Chem, 280 (17), 17286–93. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Einersen PM; Moore EE; Chapman MP; Moore HB; Gonzalez E; Silliman CC; Banerjee A; Sauaia A, Rapid thrombelastography thresholds for goal-directed resuscitation of patients at risk for massive transfusion. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 82 (1), 114–119. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giaever I; Keese CR, Use of electric fields to monitor the dynamical aspect of cell behavior in tissue culture. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, 33 (2), 242–7. 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wataha K; Menge T; Deng X; Shah A; Bode A; Holcomb JB; Potter D; Kozar R; Spinella PC; Pati S, Spray-dried plasma and fresh frozen plasma modulate permeability and inflammation in vitro in vascular endothelial cells. Transfusion, 53 Suppl 1, 80S–90S. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsumoto H; Takeba J; Umakoshi K; Kikuchi S; Ohshita M; Annen S; Moriyama N; Nakabayashi Y; Sato N; Aibiki M, Decreased antithrombin activity in the early phase of trauma is strongly associated with extravascular leakage, but not with antithrombin consumption: a prospective observational study. Thromb J, 16, 17. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park MS; Owen BA; Ballinger BA; Sarr MG; Schiller HJ; Zietlow SP; Jenkins DH; Ereth MH; Owen WG; Heit JA, Quantification of hypercoagulable state after blunt trauma: microparticle and thrombin generation are increased relative to injury severity, while standard markers are not. Surgery, 151 (6), 831–6. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pati S; Matijevic N; Doursout MF; Ko T; Cao Y; Deng X; Kozar RA; Hartwell E; Conyers J; Holcomb JB, Protective effects of fresh frozen plasma on vascular endothelial permeability, coagulation, and resuscitation after hemorrhagic shock are time dependent and diminish between days 0 and 5 after thaw. J Trauma, 69 Suppl 1, S55–63. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sperry JL; Guyette FX; Adams PW, Prehospital Plasma during Air Medical Transport in Trauma Patients. N Engl J Med, 379 (18), 1783. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruen DS; Brown JB; Guyette FX; Vodovotz Y; Johansson PI; Stensballe J; Barclay DA; Yin J; Daley BJ; Miller RS; et al. , Prehospital plasma is associated with distinct biomarker expression following injury. JCI Insight, 5 (8). 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Phenotyping Rho and Rac activation after trauma. Incubation with plasma from patients with injury+Shock resulted in the highest Rho activation (A) and lowest Rac activation (B), although these results were not statistically significant. Shock alone induced an increase in both Rho and Rac activation, while incubation with injury only plasma resulted in minimal change in Rac or Rho activation from control. Injury+shock plasma induced a decreased Rac/Rho ratio compared to minimal injury (C), but there was no significant difference between shock alone or injury alone groups and any of the other phenotypes.