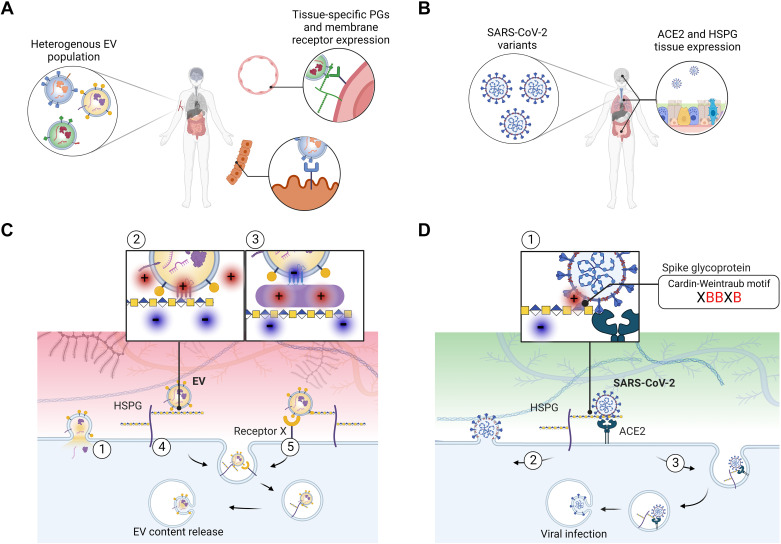

Figure 1.

Heparan sulfate (HS) as a portal of entry for EVs and SARS-CoV-2 viral particles. A: EVs carry membrane-associated proteins whose relative abundance highly depends on the status of the secreting cell, leading to heterogeneous populations of EVs in tissues and in circulation. The expression levels of proteoglycans and other cell membrane receptors at the target tissue, together with specific EV-ligand proteins likely dictate EV tropism. B: SARS-CoV-2 particles are relatively less heterogeneous than EVs in their molecular composition; however SARS-CoV-2 variants differ in the efficiency of infection. ACE2 and HSPG tissue expression influence SARS-CoV-2 infection. C: mechanistically, EV transfer to recipient cells may occur via 1) direct fusion of lipid membranes or via an endocytic route following attachment to membrane receptors. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) can 2) bind to polybasic domains of membrane EV proteins or 3) proteins associated to the EV surface by electrostatic interactions. After initial attachment, 4) HSPGs may trigger internalization or 5) facilitate EV uptake by other membrane receptors. After internalization, EV contents may be recycled or released in the recipient cell. D: similarly, SARS-CoV-2 uptake depends on initial binding of the spike protein to HSPGs through Cardin-Weintraub motifs within the S1-S2 region (where X is a hydrophobic amino acid and B denotes a positively charged (red) basic residue). Further, 1) binding to ACE2 facilitates 2) viral fusion with the cell membrane or 3) receptor-mediated endocytosis, leading to viral infection. EVs, extracellular vesicles.