Abstract

Background

Low-energy fractures (LEF) are more frequent in people with schizophrenia than the general population, and the role of prolactin-increasing antipsychotics is unknown.

Study design

We conducted a nested case-control study using Finnish nationwide registers (inpatient, specialized outpatient care, prescription drug purchases). We matched each person with schizophrenia aged 16–85 years and incident LEF (cases) with 5 age/sex/illness duration-matched controls with schizophrenia, but no LEF. We investigated the association between cumulative exposure (duration, and Defined Daily Doses, DDDs) to prolactin-increasing/sparing antipsychotics and LEF. Adjusted conditional logistic regression analyses were performed. Sensitivity analyses were conducted.

Study results

Out of 61 889 persons with schizophrenia between 1972 and 2014, we included 4960 cases. Compared with 24 451 controls, 4 years or more of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics was associated with increased risk of LEF (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) from aOR = 1.22, 95%CI = 1.09–1.37 to aOR = 1.38, 95%CI = 1.22–1.57, for 4–<7/>13 years of exposure, respectively), without a significant association for prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. All cumulative doses higher than 1000 DDDs of prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were associated with LEF (from aOR = 1.21, 95%CI = 1.11–1.33, 1000–<3000 DDDs, to aOR = 1.64, 95%CI = 1.44–1.88, >9000 DDDs). Only higher doses of prolactin-sparing antipsychotics reached statistical significance (aOR = 1.24, 95%CI = 1.01–1.52, 6000–<9000 DDDs, aOR = 1.45, 95%CI = 1.13–1.85, >9000 DDDs). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the main analyses for prolactin-increasing antipsychotics. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, significant associations were limited to extreme exposure, major LEF, older age group, and males.

Conclusions

Long-term exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics at any dose, and high cumulative doses of prolactin-sparing antipsychotics is associated with significantly increased odds of LEF. Monitoring and addressing hyperprolactinemia is paramount in people with schizophrenia receiving prolactin-increasing antipsychotics.

Keywords: antipsychotic, bone fracture, schizophrenia, hyperprolactinemia, prolactin, psychiatry

Introduction

Prolactin has numerous effects in humans, including on bone mineral density (BMD, ie, quantity of calcium and minerals in the bone).1 Since antipsychotics can induce hyperprolactinemia by blocking D2 dopamine receptors in the tubero-infundibular pathway,2 it is not surprising that a meta-analysis showed that prolactin-increasing antipsychotics worsen BMD.3 Low BMD can in turn increase the risk of low-energy fractures (LEF), such as vertebral fractures. LEF are a result of falling from standing height or less, as opposed to high-energy fracture due to any other type of trauma.4 Consistently, several meta-analyses have confirmed the association between antipsychotics and fractures, but without deliberately focusing on LEF.5–8 The most recent meta-analysis included 29 studies and showed that exposure to antipsychotics is associated with 57% increased odds of hip fracture, and 17% increased odds of any fracture, with similar figures for first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics.5 Meta-analyses of observational studies have been pooled in an umbrella review, which confirmed the association between antipsychotics and hip fracture (odds ratio/OR = 1.57, 95% confidence interval/CI = 1.42–1.74, n = 5 288 118), yet not with convincing evidence, and with GRADE assessment indicating low certainty, with several biases.9 After this most recent umbrella review, recent additional studies have focused on fractures without specific analyses of LEF,10 confirming the association between antipsychotics and bone fractures. Of note, these previous meta-analyses did not restrict their samples to subjects with schizophrenia,5,6,8 and when restricted to schizophrenia, only conducted a qualitative systematic review on the impact of antipsychotics on the risk of fractures.7

Limited evidence on the other hand explored the association between antipsychotics and LEF, specifically. One meta-analysis recently focused on fragility hip fractures.11 this meta-analysis included eight studies that reported an association between antipsychotics and an 85% increased odds of hip fractures, pooling data from 57 517 fractures. Among these studies, none differentiated between prolactin-increasing and prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, one differentiated between first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics, many were affected by confounding by indication, given that they did not restrict analyses to samples with a specific mental disorders (ie, schizophrenia), instead restricting analyses to elderly subjects,12,13 or primarily focusing on other medications (ie, benzodiazepines, proton pump inhibitors, costicosteroids).

Given that the putative mechanism of action of antipsychotics on bone health is hyperprolactinemia,1,14,15 studies investigating the association between antipsychotics and LEF should ideally separate prolactin-increasing antipsychotics from prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. To the best of our knowledge, to date no study has investigated the association between prolactin-increasing and prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, following patients for over a decade, with a large age range, controlling for confounding by indication, in a sample of people with schizophrenia that is representative of the general population. This work aims to fill this gap. We hypothesized that longer-term exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics would be associated in a cumulative dose-dependent fashion with LEF in patients with schizophrenia who, as a population in general, may have an increased risk of LEF due to decreased exercise and sun exposure.

Methods

Study Design, Cohort, Cases, and Controls

We performed a nested case-control study. The database included all 61 889 persons aged 16 years or older diagnosed with schizophrenia in inpatient care at least once from 1972 to 2014 in Finland. People with schizophrenia were identified from the hospital discharge register (the ICD codes F20 and F25 [ICD-10] and 295 [ICD-8 and ICD-9]). Data from the hospital discharge register (all hospital care periods with diagnoses between 1972 and 2017, and specialized outpatient care visits with diagnoseis between 1998 and 2017), causes of death (1972–2017) and prescription register (reimbursed prescription drug purchases between 1995 and 2017) were collected for this base cohort. All registers were linked by personal identification number (each resident has one in Finland). Ethnicity data were not collected.

Hospital discharge register data were also used to identify our cases, namely subjects hospitalized (inpatient or emergency room) or treated in specialized hospital-based outpatient centers for fractures, as previously done.16 Primary care visits were not included. We narrowed our case definition to LEF, split in major LEF (ICD-10 codes S22.0, S22.1, S32.0, S52.5, S42.2, S72.0, S72.1, S72.2) or minor LEF (S22.3, S22.4, S32.1, S32.3, S32.4, S32.5, S32.8, S42.4, S72.4, S82.5, S82.6). The exact ICD definitions of each diagnostic code is reported in the eMethods. LEF had to be incident (i.e., no previous LEF since 1996), occur after the diagnosis of schizophrenia, and occur between 2000 and 2017. We excluded persons who had potential external causes for fracture, defined by the following ICD codes (T, S07-S08, S17-S18, S28, S38, S47-S48, S57-S58, S67-S68, S77-S78, S87-S88, S97-S98) (eMethods). All cases had at least 5 years of follow-up for medication use before their index date (the prescription register opened in 1995).

For each case and via incidence density sampling,17 we selected up to five controls without incident LEF among subjects with schizophrenia. The matching criteria were age (±1 year), sex, time since first schizophrenia diagnosis (±1 year), and not having a diagnosis of LEF before the matching. The same exclusion criteria were applied to controls as for the cases, and controls could become cases later (after >1 year). The same dDate of LEF diagnosis of the case was assigned as the index date for the controls.

Exposure

The main exposure measure was exposure to antipsychotics (defined as Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] classification code N05A, excluding lithium N05AN01), collected from the prescription register, which provides data on all reimbursed prescription drug purchases from pharmacies with complete coverage since 1995 in Finland. Data recorded include date of dispensing, ATC code, name of drug product, dose strength, package size, the number of packages dispensed, and dispensed amount in Defined Daily Doses (DDDs). Information on prescribed dosing or the indication for prescribing are not available. Any formulation of antipsychotics was included. Antipsychotics were categorized as prolactin-increasing or prolactin-sparing antipsychotics (including clozapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole) based on a review of previous evidence18–21 (eMethods). Prolactin-sparing antipsychotic use was restricted to the time when such antipsychotics were used alone, without concomitant prolactin-increasing antipsychotics (ie, exposure time of prolactin-increasing antipsychotic use in combination with prolactin-sparing antipsychotic use was coded as prolactin-increasing antipsychotic use). Prolactin-increasing and prolactin-sparing antipsychotic use was categorized as cumulative duration (up to 1 year, 1–<4 years, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years), and as cumulative dose (<500, 500–<1000, 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, 6000–<9000, and ≥9000 cumulative sum of DDD). Of note, 1 DDD corresponds to 10 mg of olanzapine or 400 mg of quetiapine. Duration of exposure was derived with the PRE2DUP method.22 This method is based on mathematical modeling of personal drug purchasing behavior from drug dispensing recorded in the prescription register. Each Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code was modeled separately and then these periods were processed to larger categories (prolactin-increasing and prolactin-sparing antipsychotic use periods). During, e.g., prolactin-increasing antipsychotic use, a person could have used more than one of the mentioned antipsychotics concomitantly or changed from one drug to another if there was no interruption in drug availability.

Covariates

The following covariates were derived on the basis of hospital discharge and prescription register data as diagnosed or used ever before the index date and used for adjustments in the statistical analyses: substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, the number of children, dementia, other neurological disease (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), stroke, head injury, liver disease, renal disease, active cancer, hormone-replacement therapy, cumulative duration of inpatient care, and current use (within 30 days before index date) of benzodiazepines and related drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. As standardized difference between cases and controls for age was >10%, the models were also adjusted for age.

Analyses were also adjusted for prolactin-increasing versus prolactin-sparing antipsychotic use in the same exposure categories as the analysis was made (duration, DDD).

Statistical Analyses and Outcomes

We conducted conditional logistic regression analyses as per matched design (matching group as strata). Multivariable models were adjusted for the factors mentioned above. Matching factors were controlled for by study design, and adjusted for in case of a standardized difference higher than 10%. The rReference category was less than 1 year of exposure, or less than 500 DDDs (including never-users). We chose this reference category, as there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials lasting up to 12 months of any increased risk of LEF. The main analysis was the association between the cumulative duration of prolactin-increasing drugs with LEF. Several sensitivity analyses were performed splitting LEF into major and minor LEF, by age group (<65 vs >65 years old), and by sex. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted on the duration of prolactin-increasing antipsychotic use when concomitant use time with aripiprazole was removed, on olanzapine, and on the average DDDs per day for both prolactin-increasing and prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. To calculate the incidence rate of LEF among persons with schizophrenia, we restricted the base cohort with the same inclusion/exclusion criteria as utilized for identification of cases and controls. We used SAS 9.4 for statistical analyses.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Among people with schizophrenia, we included 4960 who had incident LEF, and 24 451 matched controls. The flow of cases and control selection is reported in supplementary figure 1. In cases and controls, around 61.5% were females, and the mean age was around 62-years-old (standard deviation/SD around 13 years) (table 1). The average time since the diagnosis of schizophrenia was 21.6 years (SD = 11.3 years). Overall, 71.5% of the LEF were major LEF, and 28.5% were minor LEF. Regarding exposure, the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic was risperidone (n = 8893, 32% [N = 1571] among cases and 30% [N = 7322] among controls), followed by olanzapine (n = 7869, 29% [N = 1430] among cases and 26% [N = 6439] among controls), levomepromazine (n = 7716, 28% [N = 1406] among cases and 26% [N = 6310] of controls), thioridazine (n = 7104, 25% [N = 1241] among cases and 24% [N = 5863] of controls), and perphenazine (n = 6978, 23% [N = 1155] among cases and 24% [N = 5823] among controls).

Table 1.

Characteristics of People With Schizophrenia With and Without Low-Energy Fractures

| Control | Case With LEF | Standardized Difference, % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 24451 | N = 4960 | ||

| Women % (N) | 61.4 (15 014) | 61.8 (3065) | 0.4 |

| Mean age (SD) | 61.9 (13.1) | 62.4 (13.2) | 10.7 |

| Time since schizophrenia diagnosis (years) | 21.6 (11.3) | 21.6 (11.4) | 1.1 |

| Type of LEF | |||

| Major LEF | NA | 71.5 (3548) | |

| Minor LEF | NA | 28.5 (1412) | |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 92.2 (22 544) | 92.7 (4600) | 0.7 |

| 1 | 5.0 (1224) | 4.7 (232) | 0.5 |

| ≥2 | 2.8 (683) | 2.6 (128) | 0.4 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | 33.1 (8092) | 38.2 (1892) | 5.2 |

| Diabetes | 16.8 (4097) | 18.6 (923) | 2.1 |

| Substance abuse | 12.1 (2957) | 16.5 (817) | 5.2 |

| Asthma/COPD | 7.1 (1728) | 10.1 (500) | 4.0 |

| Renal disease | 5.6 (1370) | 7.5 (374) | 2.8 |

| Head injury | 5.1 (1250) | 8.5 (419) | 4.7 |

| Stroke | 4.2 (1017) | 5.5 (271) | 2.0 |

| Active cancer | 3.4 (841) | 4.8 (238) | 2.2 |

| Dementia | 3.3 (800) | 4.2 (208) | 1.5 |

| Other neurological disease | 1.1 (279) | 1.6 (77) | 0.9 |

| Liver disease | 0.8 (198) | 1.0 (51) | 0.5 |

| Cumulative duration of systemic hormone replacement therapy use (years) | |||

| 0 | 87.6 (21 430) | 87.9 (4358) | 0.3 |

| <1 | 5.2 (1260) | 5.0 (248) | 0.2 |

| 1–5 | 3.8 (931) | 4.0 (198) | 0.3 |

| ≥5 | 3.4 (830) | 3.2 (156) | 0.4 |

| Current medication use (within 30 days before LEF) | |||

| Benzodiazepines and related drugs | 27.9 (6816) | 31.7 (1574) | 4.0 |

| SSRIs | 12.2 (2994) | 14.2 (704) | 2.4 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 2.6 (630) | 2.8 (138) | 0.4 |

| Antipsychotics | |||

| Risperidone | 29.9 (7322) | 33.5 (1571) | |

| Olanzapine | 26.3 (6439) | 30.5 (1430) (30.5%) | |

| Levomepromazine | 25.8 (6310) | 30.0 (1406) | |

| Thioridazine | 24.0 (5863) | 26.4 (1241) | |

| Perphenazine | 23.8 (5823) | 24.6 (1155) | |

Note: Subjects could have been exposed to more than one medication, hence the percentage for each medication sums up to more than 100%. A standardized difference >10% was interpreted as a substantial difference between the groups.

Over one out of three persons with schizophrenia had cardiovascular disease, and almost one fifth had diabetes. Other clinical characteristics are reported in table 1. The distribution of individual antipsychotics across categories of exposure is reported in supplementary table 1.

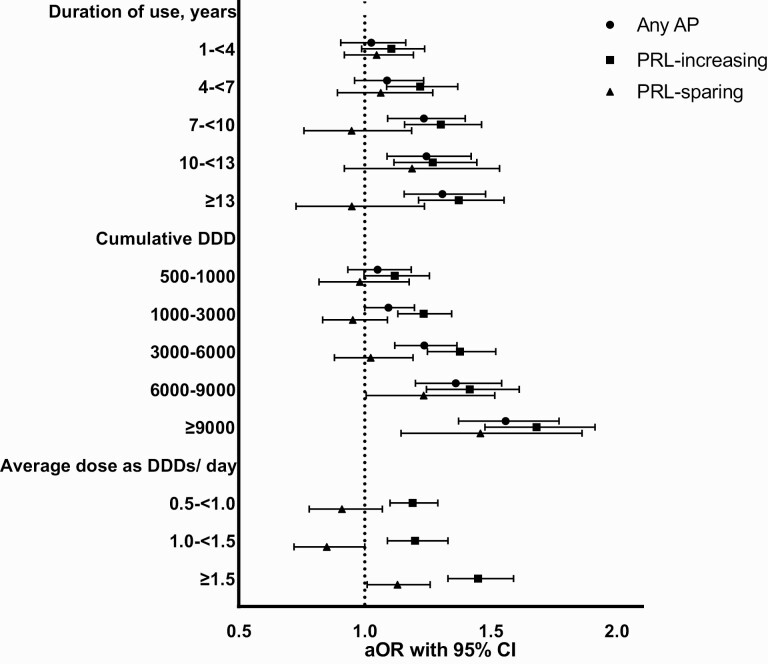

Overall, 10.4% of the cohort eligible for LEF analyses (N = 47 669) had incident LEF during 2000–2017, resulting in a cumulative incidence rate of 0.82 LEFs per 100 person-years among persons with schizophrenia. Results of the main and sensitivity analyses are graphically reported in figure 1, with all details in tables 2–4. As reported in table 2, compared with 24 451 controls, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 22%, 30%, 27%, and 38% increased odds of LEF, respectively, compared with <1 year of exposure. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, no significant association between duration of exposure and LEF emerged. Considering dose, all cumulative doses higher than 1000 DDDs of prolactin-increasing antipsychotics, namely 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, 6000–<9000, and >9000 DDDs, were significantly associated with a 21%, 35%, 40%, and 64% increased odds of LEF, compared with <500 DDDs of prolactin-increasing antipsychotic use. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, a significant association only emerged for 6000–<9000 and >9000 DDDs, with a 24% and 45% increased odds of LEF.

Fig. 1.

Duration, cumulative, and average daily exposure to antipsychotics and low-energy fractures. AP, antipsychotic; DDD, defined daily dose; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; PRL, prolactin.

Table 2.

Association Between Exposure to Any Antipsychotics, Prolactin-increasing Antipsychotics, and Prolactin-sparing Antipsychotics and Low-Energy Fractures in People With Schizophrenia

| Duration | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted ORa | DDD | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted ORa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 16.6 (4718) | 19.3 (822) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 33.4 (8175) | 30.3 (1504) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 11.7 (2980) | 12.2 (579) | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 500–<1000 | 9.1 (2219) | 8.7 (429) | 1.04 (0.93–1.18) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) |

| 4–<7 y | 14.0 (3425) | 14.0 (695) | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | 1000–<3000 | 22.8 (5578) | 22.1 (1096) | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) | 1.08 (0.98–1.18) |

| 7–<10 y | 15.8 (3628) | 14.8 (783) | 1.28 (1.13–1.45) | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 3000–<6000 | 17.1 (4187) | 18.1 (898) | 1.24 (1.12–1.36) | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) |

| 10–<13 y | 13.3 (3088) | 12.6 (660) | 1.28 (1.13–1.46) | 1.25 (1.09–1.42) | 6000–<9000 | 8.6 (2101) | 9.6 (477) | 1.36 (1.20–1.54) | 1.35 (1.18–1.53) |

| ≥13 y | 28.7 (6612) | 27.0 (1421) | 1.33 (1.18–1.49) | 1.32 (1.17–1.50) | ≥9000 | 9.0 (2191) | 11.2 (556) | 1.57 (1.39–1.78) | 1.52 (1.33–1.73) |

| Prolactin-increasing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 21.4 (6203) | 25.4 (1059) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 36.9 (9023) | 31.9 (1583) | Reference | |

| 1–<4 y | 12.6 (3157) | 12.9 (625) | 1.15 (1.02–1.28) | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 500–<1000 | 9.4 (2308) | 9.1 (452) | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 1.11 (0.98–1.24) |

| 4–<7 y | 14.5 (3361) | 13.8 (721) | 1.27 (1.14–1.43) | 1.22 (1.09–1.37) | 1000–<3000 | 23.6 (5762) | 24.3 (1207) | 1.22 (1.12–1.33) | 1.21 (1.11–1.33) |

| 7–<10 y | 15.3 (3454) | 14.1 (759) | 1.34 (1.19–1.50) | 1.30 (1.16–1.47) | 3000–<6000 | 15.8 (3864) | 17.5 (870) | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) | 1.35 (1.23–1.50) |

| 10–<13 y | 12.3 (2865) | 11.7 (609) | 1.28 (1.13–1.45) | 1.27 (1.12–1.45) | 6000–<9000 | 7.1 (1744) | 7.9 (392) | 1.37 (1.21–1.56) | 1.40 (1.23–1.59) |

| ≥13 y | 23.9 (5411) | 22.1 (1187) | 1.36 (1.22–1.51) | 1.38 (1.22–1.57) | ≥9000 | 7.2 (1750) | 9.2 (456) | 1.62 (1.43–1.84) | 1.64 (1.44–1.88) |

| Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 84.6 (20 741) | 84.8 (4196) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 81.7 (19 971) | 81.2 (4029) | Reference | |

| 1–<4 y | 6.7 (1474) | 6.0 (330) | 1.12 (0.99–1.27) | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 500–<1000 | 3.1 (746) | 3.2 (157) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 0.99 (0.83–1.19) |

| 4–<7 y | 3.4 (783) | 3.2 (170) | 1.08 (0.91–1.29) | 1.10 (0.92–1.31) | 1000–<3000 | 6.4 (1575) | 6.2 (305) | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | 0.97 (0.84–1.10) |

| 7–<10 y | 2.1 (579) | 2.4 (104) | 0.89 (0.72–1.11) | 0.98 (0.78–1.22) | 3000–<6000 | 4.9 (1191) | 4.9 (241) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) |

| 10–<13 y | 1.6 (379) | 1.6 (81) | 1.07 (0.83–1.37) | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 6000–<9000 | 2.4 (579) | 2.6 (131) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 1.24 (1.01–1.52) |

| ≥13 y | 1.6 (495) | 2.0 (79) | 0.79 (0.61–1.01) | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | ≥9000 | 1.6 (389) | 2.0 (97) | 1.29 (1.02–1.64) | 1.45 (1.13–1.85) |

Note: DDD, defined daily dose; OR, odds ratio.

aAdjusted for: age, substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, the number of children, dementia, other neurological diseases (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), stroke, head injury, liver disease, renal disease, active cancer, hormone-replacement therapy, cumulative duration of inpatient care, and current use (within 30 days before index date) of benzodiazepines and related drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors.

Table 3.

Exposure to Prolactin-increasing or Prolactin-sparing Antipsychotics, and Low-energy Fractures: Sensitivity Analyses by Sex

| Duration | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | DDD | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||||||

| Prolactin-increasing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 23.5 (3530) | 19.8 (606) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 36.4 (5456) | 31.5 (965) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 12.7 (1901) | 12.3 (376) | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) | 500–1000 | 10.1 (1526) | 9.7 (296) | 1.11 (0.96–1.28) | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) |

| 4–<7 y | 14.3 (2145) | 14.7 (451) | 1.24 (1.07–1.43) | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 1000–3000 | 24.7 (3706) | 25.7 (788) | 1.24 (1.11–1.38) | 1.21 (1.09–1.36) |

| 7–<10 y | 14.5 (2178) | 15.7 (480) | 1.33 (1.15–1.55) | 1.30 (1.12–1.51) | 3000–6000 | 15.6 (2336) | 17.6 (539) | 1.39 (1.22–1.57) | 1.35 (1.19–1.54) |

| 10–<13 y | 12.4 (1858) | 12.8 (392) | 1.27 (1.09–1.49) | 1.25 (1.06–1.48) | 6000–9000 | 6.7 (1006) | 6.9 (210) | 1.27 (1.07–1.51) | 1.28 (1.07–1.52) |

| ≥13 y | 22.7 (3402) | 24.8 (760) | 1.40 (1.21–1.62) | 1.42 (1.21–1.66) | ≥9000 | 6.6 (9846) | 8.7 (267) | 1.68 (1.43–1.99) | 1.65 (1.39–1.96) |

| Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 86.2 (12 946) | 85.9 (2632) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 83.6 (1256) | 83.3 (2553) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 5.8 (864) | 6.1 (186) | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | 500–1000 | 2.9 (4386) | 3.0 (93) | 1.05 (0.83–1.32) | 1.00 (0.79–1.26) |

| 4–<7 y | 2.9 (433) | 3.2 (99) | 1.14 (0.90–1.43) | 1.18 (0.93–1.49) | 1000–3000 | 6.1 (9166) | 5.6 (173) | 0.95 (0.80–1.13) | 0.94 (0.79–1.13) |

| 7–<10 y | 2.1 (310) | 1.9 (59) | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 3000–6000 | 4.3 (6386) | 4.5 (137) | 1.08 (0.88–1.31) | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) |

| 10–<13 y | 1.4 (214) | 1.3 (41) | 0.96 (0.68–1.36) | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | 6000–9000 | 1.9 (2906) | 2.2 (67) | 1.18 (0.89–1.55) | 1.24 (0.93–1.64) |

| ≥13 y | 1.7 (247) | 1.6 (48) | 0.97 (0.71–1.34) | 1.22 (0.86–1.72) | ≥9000 | 1.2 (1746) | 1.4 (42) | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) | 1.38 (0.96–1.99) |

| Men | |||||||||

| Prolactin-increasing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 28.3 (2673) | 23.9 (453) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 37.8 (3566) | 32.6 (618) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 13.3 (1256) | 13.1 (249) | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) | 500–1000 | 8.3 (7876) | 8.2 (156) | 1.14 (0.94-1.38) | 1.13 (0.93–1.38) |

| 4–<7 y | 12.9 (1216) | 14.3 (270) | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) | 1000–3000 | 21.8 (2056) | 22.1 (419) | 1.20 (1.04–1.38) | 1.22 (1.06–1.40) |

| 7–<10 y | 13.5 (1276) | 14.7 (279) | 1.34 (1.12–1.61) | 1.31 (1.08–1.57) | 3000–6000 | 16.2 (1526) | 17.5 (331) | 1.30 (1.11–1.51) | 1.36 (1.16–1.59) |

| 10–<13 y | 10.7 (1007) | 11.5 (217) | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) | 1.31 (1.07–1.62) | 6000–9000 | 7.8 (7356) | 9.6 (182) | 1.51 (1.25–1.83) | 1.57 (1.29–1.92) |

| ≥13 y | 21.3 (2009) | 22.5 (427) | 1.29 (1.09–1.53) | 1.34 (1.11–1.63) | ≥9000 | 8.1 (7666) | 10.0 (189) | 1.53 (1.26–1.86) | 1.66 (1.35–2.04) |

| Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 82.6 (7795) | 82.5 (1564) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 78.6 (7416) | 77.9 (1476) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 6.5 (610) | 7.6 (144) | 1.18 (0.97–1.43) | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | 500–1000 | 3.3 (3086) | 3.4 (64) | 1.05 (0.80–1.39) | 0.98 (0.74–1.31) |

| 4–<7 y | 3.7 (350) | 3.8 (71) | 1.01 (0.78–1.32) | 0.99 (0.76–1.30) | 1000–3000 | 7.0 (6596) | 7.0 (132) | 1.01 (0.83–1.24) | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) |

| 7–<10 y | 2.9 (269) | 2.4 (45) | 0.83 (0.59–1.15) | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) | 3000–6000 | 5.9 (5536) | 5.5 (104) | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | 0.97 (0.76–1.22) |

| 10–<13 y | 1.8 (165) | 2.1 (40) | 1.20 (0.84–1.71) | 1.29 (0.89–1.88) | 6000–9000 | 3.1 (2896) | 3.4 (64) | 1.14 (0.85–1.52) | 1.24 (0.92–1.68) |

| ≥13 y | 2.6 (248) | 1.6 (31) | 0.60 (0.40–0.89) | 0.74 (0.49–1.13) | ≥9000 | 2.3 (2156) | 2.9 (55) | 1.34 (0.97–1.85) | 1.50 (1.07–2.11) |

Note: DDD, defined daily dose; OR, odds ratio.

aAdjusted for: age, substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, the number of children, dementia, other neurological diseases (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), stroke, head injury, liver disease, renal disease, active cancer, hormone-replacement therapy, cumulative duration of inpatient care, and current use (within 30 days before index date) of benzodiazepines and related drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors.

Table 4.

Exposure to Prolactin-increasing or Prolactin-sparing Antipsychotics, and Low-Energy Fractures: Sensitivity Analyses by Major and Minor Low-Energy Fractures

| Duration | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR | DDD | Control % (N) | Case % (N) | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major low-energy fracture | |||||||||

| Prolactin-increasing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 24.8 (4379) | 20.5 (734) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 36.9 (6506) | 31.5 (1129) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 12.7 (2242) | 12.2 (437) | 1.15 (1.00–1.31) | 1.10 (0.97-1.26) | 500–1000 | 9.4 (1656) | 9.2 (329) | 1.15 (1.00–1.31) | 1.14 (0.99–1.30) |

| 4–<7 y | 13.4 (2367) | 14.8 (530) | 1.37 (1.19–1.56) | 1.32 (1.15-1.51) | 1000–3000 | 23.6 (4166) | 24.2 (869) | 1.23 (1.11–1.36) | 1.23 (1.11–1.37) |

| 7–<10 y | 14.6 (2566) | 15.4 (554) | 1.33(1.17–1.53) | 1.32 (1.15-1.51) | 3000–6000 | 15.9 (2806) | 17.8 (640) | 1.39 (1.24–1.56) | 1.41 (1.25–1.58) |

| 10–<13 y | 11.9 (2107) | 12.5 (449) | 1.30 (1.13–1.51) | 1.31 (1.13-1.53) | 6000–9000 | 7.1 (1246) | 8.2 (293) | 1.45 (1.25–1.68) | 1.48 (1.27–1.73) |

| ≥13 y | 22.6 (3980) | 24.6 (883) | 1.40 (1.23–1.59) | 1.47 (1.27-1.70) | ≥9000 | 7.2 (1266) | 9.1 (327) | 1.62 (1.40–1.88) | 1.68 (1.43–1.96) |

| Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 85.8 (15 139) | 85.4 (3062) | Reference | <500 | 82.9 (1466) | 82.6 (2961) | Reference | Reference | |

| 1–<4 y | 5.7 (1010) | 6.3 (225) | 1.11 (0.96–1.30) | 1.06 (0.90–1.24) | 500–1000 | 2.9 (5056) | 2.8 (102) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.94 (0.76–1.18) |

| 4–<7 y | 2.9 (505) | 3.2 (116) | 1.15 (0.93–1.41) | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | 1000–3000 | 6.0 (1066) | 5.7 (203) | 0.96 (0.81–1.12) | 0.94 (0.79–1.10) |

| 7–<10 y | 2.2 (387) | 1.8 (64) | 0.83 (0.63–1.09) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 3000–6000 | 4.5 (7906) | 4.6 (164) | 1.04 (0.87–1.25) | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) |

| 10–<13 y | 1.5 (269) | 1.8 (63) | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 1.39 (1.03–1.87) | 6000–9000 | 2.2 (3896) | 2.4 (86) | 1.12 (0.88–1.43) | 1.24 (0.96–1.60) |

| ≥13 y | 1.9 (331) | 1.6 (57) | 0.86 (0.64–1.15) | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) | ≥9000 | 1.5 (2686) | 2.0 (71) | 1.37 (1.04–1.81) | 1.54 (1.16–2.06) |

| Minor low-energy fracture | |||||||||

| Prolactin-increasing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 26.9 (1886) | 23.8 (336) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 37.1 (2596) | 33.1 (467) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 13.4 (941) | 13.8 (195) | 1.15 (0.95–1.41) | 1.11 (0.91–1.37) | 500–1000 | 9.5 (6676) | 9.3 (131) | 1.09 (0.88–1.35) | 1.05 (0.84–1.30) |

| 4–<7 y | 14.6 (1020) | 14.0 (197) | 1.07 (0.87–1.32) | 1.02 (0.82–1.27) | 1000–3000 | 23.4 (1646) | 24.3 (343) | 1.18 (1.01–1.39) | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) |

| 7–<10 y | 13.1 (919) | 14.8 (209) | 1.34 (1.08–1.66) | 1.28 (1.02–1.59) | 3000–6000 | 15.7 (1096) | 16.6 (235) | 1.24 (1.03–1.48) | 1.21 (1.01–1.47) |

| 10–<13 y | 11.0 (770) | 11.5 (162) | 1.23(0.97–1.56) | 1.17 (0.91–1.50) | 6000–9000 | 7.2 (5046) | 7.4 (105) | 1.24 (0.97–1.58) | 1.25 (0.97–1.60) |

| ≥13 y | 21.0 (1469) | 22.2 (313) | 1.26 (1.02–1.55) | 1.20 (0.95–1.52) | ≥9000 | 7.1 (4976) | 9.3 (131) | 1.60 (1.26–2.02) | 1.54 (1.20–1.97) |

| Prolactin-sparing antipsychotics | |||||||||

| <1 y | 82.1 (5749) | 82.4 (1164) | Reference | Reference | <500 | 78.3 (5486) | 77.7 (1097) | Reference | Reference |

| 1–<4 y | 6.9 (480) | 7.8 (110) | 1.15 (0.92–1.43) | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | 500–1000 | 3.5 (2486) | 4.0 (57) | 1.17 (0.86–1.57) | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) |

| 4–<7 y | 4.2 (292) | 4.0 (56) | 0.95 (0.70–1.28) | 0.91 (0.67–1.25) | 1000–3000 | 7.5 (5286) | 7.6 (107) | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) | 1.04 (0.83–1.32) |

| 7–<10 y | 2.8 (199) | 2.9 (41) | 1.01 (0.71–1.44) | 1.06 (0.73–1.54) | 3000–6000 | 6.0 (4196) | 5.5 (78) | 0.94 (0.73–1.23) | 0.93 (0.71–1.22) |

| ≥10 y | 4.1 (285) | 2.9 (41) | 0.69 (0.49–0.98) | 0.79 (0.54–1.15) | 6000–9000 | 2.8 (1956) | 3.2 (45) | 1.18 (0.84–1.67) | 1.21 (0.84–1.74) |

| * | * | * | * | * | ≥9000 | 1.8 (1296) | 2.0 (28) | 1.12 (0.72–1.75) | 1.26 (0.79–2.00) |

Note: DDD, defined daily dose; OR, odds ratio; *for minor LEF, two highest categories were combined due to low N of prolactin-sparing AP users in those.

aAdjusted for: age, substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, the number of children, dementia, other neurological diseases (Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), stroke, head injury, liver disease, renal disease, active cancer, hormone-replacement therapy, cumulative duration of inpatient care, and current use (within 30 days before index date) of benzodiazepines and related drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors.

In sensitivity analyses, results were largely consistent with the main findings. As reported in table 3, in women, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 17%, 30%, 25%, and 42% increased odds of LEF, compared with <1 year exposure. Corresponding figures for 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, 6000–<9000, and >9000 DDDs of exposure were a 21%, 35%, 28%, 65% increased odds of LEF, compared with <500 DDDs exposure. No significant association emerged for prolactin-sparing antipsychotics in women. In men, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 30%, 31%, 31%, and 34% increased odds of LEF. Corresponding figures for 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, 6000–<9000, and >9000 DDD of exposure were a 223%, 36%, 57%, 66% significantly increased odds. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, no significant association emerged with duration of exposure, and for DDDs, only >9000 DDD were associated with a 50% increased odds of LEF in men.

As reported in table 4, when restricting analyses to major LEF, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 32%, 32%, 31%, and 47% increased odds of major LEF, compared with <1 year of exposure. Corresponding figures for 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, 6000–<9000, and >9000 DDDs of exposure were a 23%, 41%, 48%, 68% significantly increased odds, compared with <500 DDDs. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, only 10-<13 years of exposure and ≥9000 DDD were significantly associated with a 39%, and 54% increased odds of major LEFs respectively. When restricting analyses to minor LEF, 7–<10 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 28% increased odds of minor LEF, as well as 1000–<3000, 3000–<6000, and >9000 DDDs with a 18%, 21%, 54% significantly increased odds. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, no significant association emerged for minor LEFs.

We also conducted sensitivity analyses by age group (supplementary table 2). In persons with schizophrenia younger than 65 years old, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 21%, 24%, and 26% increased odds of LEF compared with <1 year exposure in the same age group. No significant association emerged for prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. In subjects 65 years or older, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics were significantly associated with a 31%, 46%, 33%, and 53% increased odds of LEF. No significant association emerged for prolactin-sparing antipsychotics.

Finally, sensitivity analyses excluding duration with concomitant use of aripiprazole confirmed the main analyses, with 1–<4, 4–<7, 7–<10, 10–<13, >13 years of exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics being significantly associated with a 13%, 27%, 35%, 30%, 43% increased risk of LEF (supplementary table 3). Sensitivity analyses on olanzapine alone only found a significant association with a 14% increased odds of LEF for 1000–<3000 DDDs (supplementary table 4). Sensitivity analyses by average daily DDDs confirmed a dose-response association between prolactin-increasing and LEF, with a significantly 19%, 20%, and 43% increased odds of LEF with 0.5<1.0, 1.0–1.5, >1.5 average daily DDDs. No association emerged with prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, apart from a marginally significant 13% increased odds with >1.5 average daily DDDs (supplementary table 5, figure 1).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the association between prolactin-increasing versus prolactin-sparing antipsychotics and LEF, using a nested case-control design within a nationwide cohort of subjects with schizophrenia, over 10 years of follow-up, and accounting for duration and cumulative dose of exposure. Results of the main analyses show that there is a duration- and dose-response association between exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics and LEF, which extends to males, females, major LEF, minor LEF, people younger than 65 years old, or aged 65 or older. For prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, the association was present only for extreme exposure duration or dose, and limited to major LEF, males, and older subjects. Moreover, a dose-response association emerged between the average daily dose of prolactin-increasing antipsychotics.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of evidence on the impact of prolactin elevation on bone status and broader clinical considerations. First, in both operationalization of cumulative exposure to prolactin-increasing antipsychotics, i.e., duration in years and dose in DDDs, there is a clear dose-response association pattern, with the magnitude of the effect size becoming larger with larger exposure. Taken together with the exposure (i.e., antipsychotic treatment) occurring before the outcome (i.e., incident LEF) that excludes the risk of reverse causality, and the plausible pathogenetic mechanism, the results of this study might suggest a causal association. According to animal models, a certain amount of prolactin is needed for bone formation and maintenance, modulating the action of osteoblasts, indicated by the finding that prolactin receptor −/− mouse models showed a reduction of bone mineral density in adult mice.23 On the other hand, several studies have shown that hyperprolactinemia adversely affects bone status. A first report published back in 1980 described 14 women 20 to 40 years of age with secondary amenorrhea due to hyperprolactinemia who were not taking antipsychotics or other medications known to affect bone mineral density.24 Authors compared bone mineral density with age-matched females, showing lower bone mineral density (BMD) in women with hyperprolactinemia.24 One further study reported a high prevalence of radiological vertebral fractures in women with prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas.25

Additional studies explored the possible role of sex hormones in mediating the association between hyperprolactinemia and poor BMD. In women, hyperprolactinemia is strictly associated with low estrogen levels,1 and women with hyperprolactinemia and low estrogen levels have particularly low BMD levels,24 suggesting a mediating effect of estrogens. The role of estrogens on bone health is independent from hyperprolactinemia. For instance, amenorrhea has been a key diagnostic feature of anorexia nervosa until before DSM-5 and remains frequent with updated diagnostic criteria (that do not require amenorrhea).26 Osteoporosis and fractures are established complications of anorexia nervosa, where estrogen levels are low as a consequence of low body weight and poor nutritional status.27 On the other hand, a study that included amenorrheic women with and without hyperprolactinemia, showed that only those with hyperprolactinemia had decreased BMD, and that estrogen levels did not correlate with BMD.28 In men, a study confirmed the association between hyperprolactinemia and poor bone status, and ruled out any mediating role of hypogonadism.29 Taken together, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that sex hormones mediate the action of prolactin on bone, and prolactin levels should thus be monitored. Monitoring is of particular importance when considering additional untoward effects of hyperprolactinemia, including a possibly increased risk of breast cancer.21

Avoiding hyperprolactinemia is an important consideration in the clinical management of persons in need of antipsychotic treatment, and encompasses prevention of hyperprolactinemia, monitoring of prolactin levels, and treatment of hyperprolactinemia. Prevention of hyperprolactinemia can be successfully achieved by prescribing prolactin-sparing antipsychotics. Among prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, quetiapine seems less effective than other antipsychotics,30 and clozapine is the treatment of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia,31 but due to potentially severe adverse effects cannot be first-line treatment.32 Hence, other prolactin-sparing antipsychotics, such as the partial D2 agonists, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole or cariprazine, or lumateperone,33 may be considered if efficacious and otherwise tolerated. Regular monitoring of prolactin levels is also warranted at least during the titration and/or at the target dose of prolactin-raising antipsychotics, as some individual variability might exist in the proneness to and clinical manifestation of hyperprolactinemia, and prolactin measurement only in those with symptoms would miss many cases with hyperprolactinemia. For those patients with hyperprolactinemia during treatment with prolactin-increasing antipsychotics, 2 options are possible. First, in case a switch from a prolactin-raising to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic is not feasible, augmentation with a partial D2 agonist, eg, aripiprazole, starting at low doses is an effective option,34,35 although 10 and 20 mg of adjunctive aripiprazole were superior to 5 mg in reducing prolactin levels when added to ongoing treatment with prolactin-increasing antipsychotics.20 Second, in absence of previous inefficacy, aripiprazole (or brexpiprazole, cariprazine or lumateperone) may also be a reasonable candidate for switching patients with hyperprolactinemia, given beneficial effects on bone metabolism,36 together with essentially overlapping efficacy and safer profile compared with other antipsychotics, beyond prolactin levels.19,37 Also, aripiprazole is currently the only antipsychotic with a long-acting injectable (LAI) formulation that does not increase prolactin.38 LAIs are superior to oral formulation on a number of outcomes,39 and are protective against death.40

This study has several strengths and limitations. Strengths include that this study is the first nested case-control study specifically categorizing antipsychotics into prolactin-increasing or prolactin-sparing, considering LEF and not any fracture as an outcome, within a nationwide cohort of subjects with schizophrenia, controlling for confounding by indication (ie, schizophrenia). Also results clearly show a duration- and dose-response association between prolactin-increasing antipsychotics and LEF, which together with study design ensuring that exposure precedes the outcome, and a plausible mechanism justifying the association (ie, hyperprolactinemia), suggest a potentially causal association between exposure and outcome. Finally, this is the first study conducting analyses and confirming consistent results in both males and females.

Limitations are present as well. First, since this is not a randomized trial, unmeasured confounders might have affected the results, given that bone health and prolactin metabolism are complex and affected by multiple factors. Second, we could not control for risk factors for poor bone status, including in particular smoking and alcohol use (even though we controlled for substance use disorder) as well as weight-bearing exercise, calcium-containing diet, and sun exposure. Third, clinical and lifestyle factors, including and beyond smoking and alcohol use, might have led to the prescribing of prolactin-increasing antipsychotics. However, it should be considered that the vast majority of patients with extreme exposure to prolactin-sparing antipsychotics were patients exposed to clozapine, which implies treatment-resistant and severe clinical pictures. Fourth, prolactin elevation has been associated with breast cancer risk in females and with and sexual and reproductive system dysfunction in both males and females,2 but we did not focus on these related tolerability aspects in this study. Fifth, while our results apply at a group level, individual variation exists in prolactin response to antipsychotics,41 as well as, very likely, with regards to the relationship between prolactin levels and osteopenia or osteoporosis risk. More research is clearly needed in this personalized risk assessment area. Finally, no patient in this study was prescribed brexpiprazole, cariprazine, lurasidone, lumateperone, or ziprasidone. Hence, results cannot be extended to these medications, and future studies are required to extend the evidence to the effect of those agents.

In conclusion, this study converges with previous findings,3 supporting a less favorable safety profile of prolactin-increasing than prolactin-sparing antipsychotics on BMD, but extending to risk of LEF. In subjects treated with prolactin-increasing antipsychotics, prolactin levels should be monitored and hyperprolactinemia should be avoided when possible and treated when it occurs, either via switching from a prolactin-increasing to a less -prolactin-raising antipsychotic or augmentation with a partial D2 agonist.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MS has received honoraria from/has been a consultant for Angelini, Lundbeck, Otsuka. HT, AT and JT have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their employing institution. HT reports personal fees from Janssen-Cilag and Otsuka. ML has received honoraria from/has been a consultant for: Janssen, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Medscape, Orion, Otsuka, Recordati and Sunovion. JT has been a consultant and/or advisor to and/or has received honoraria from: Eli Lilly, Evidera, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Orion, Otsuka, Mediuutiset, Sidera, and Sunovion. CUC has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Aristo, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cardio Diagnostics, Cerevel, CNX Therapeutics, Compass Pathways, Darnitsa, Gedeon Richter, Hikma, Holmusk, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, MedInCell, Merck, Mindpax, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Newron, Noven, Otsuka, Pharmabrain, PPD Biotech, Recordati, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Seqirus, SK Life Science, Sunovion, Sun Pharma, Supernus, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Relmada, Reviva, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He received royalties from UpToDate and is also a stock option holder of Cardio Diagnostics, Mindpax, and LB Pharma. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Contributor Information

Marco Solmi, Department of Psychiatry, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Mental Health, The Ottawa Hospital, Ontario, Canada; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) Clinical Epidemiology Program University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Markku Lähteenvuo, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio, Finland.

Christoph U Correll, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany; Department of Psychiatry and Molecular Medicine, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Hempstead, Uniondale, NY, USA; The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Psychiatry Research, Northwell Health, Glen Oaks, NY, USA.

Antti Tanskanen, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio, Finland; Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Center for Psychiatry Research, Stockholm City Council, Stockholm, Sweden.

Jari Tiihonen, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio, Finland; Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Center for Psychiatry Research, Stockholm City Council, Stockholm, Sweden.

Heidi Taipale, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio, Finland; Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Center for Psychiatry Research, Stockholm City Council, Stockholm, Sweden; School of Pharmacy, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland.

Funding

This study was funded by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health through the developmental fund for Niuvanniemi Hospital. HT was funded by Academy of Finland (grants 315969, 320107, 345326)

Author Contributions

HT and MS were responsible for the overall study concept and design. HT did the analytic design. HT did the data analysis and both HT and AT had access to, and validated, the data. HT and MS wrote the first draft. All authors interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data Availability

Data collected for this study are proprietary of the Finnish government agencies Social Insurance Institution of Finland, National Institute for Health and Welfare, which granted researchers permission and access to the data. The data that support these findings of this study are available from these authorities, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The code used to analyze these data is available upon request from the corresponding author, for purposes of reproducing the results.

References

- 1. Bernard V, Young J, Binart N.. Prolactin—a pleiotropic factor in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(6):356–365. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Hert M, Detraux J, Peuskens J.. Second-generation and newly approved antipsychotics, serum prolactin levels and sexual dysfunctions: a critical literature review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(5):605–624. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.906579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tseng P-T, Chen Y-W, Yeh P-Y, Tu K-Y, Cheng Y-S, Wu C-K.. Bone mineral density in schizophrenia: an update of current meta-analysis and literature review under guideline of PRISMA. Medicine (Baltim). 2015;94(47):e1967–e1967. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diamantopoulos AP, Rohde G, Johnsrud I, Skoie IM, Hochberg M, Haugeberg G.. The epidemiology of low- and high-energy distal radius fracture in middle-aged and elderly men and women in southern Norway. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papola D, Ostuzzi G, Thabane L, Guyatt G, Barbui C.. Antipsychotic drug exposure and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;33(4):181–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee S-H, Hsu W-T, Lai C-C, et al. Use of antipsychotics increases the risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(4):1167–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3881-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stubbs B, Gaughran F, Mitchell AJ, et al. Schizophrenia and the risk of fractures: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(2):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oderda LH, Young JR, Asche CV, Pepper GA.. Psychotropic-related hip fractures: meta-analysis of first-generation and second-generation antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(7-8):917–928. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papola D, Ostuzzi G, Gastaldon C, et al. Antipsychotic use and risk of life-threatening medical events: umbrella review of observational studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(3):227–243. doi: 10.1111/acps.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. González Tejón S, Ibarra Jato M, Fernández San Martín MI, Prats Uribe A, Real Gatius J, Martin-Lopez LM.. Hip fractures in patients treated with antipsychotic drugs. Study of retrospective cohorts in Catalonia TT—Fracturas de cadera en pacientes tratados con fármacos antipsicóticos. Estudio de cohortes históricas en Cataluña. Aten Primaria. 2022;54(2):102171. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2021.102171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mortensen SJ, Mohamadi A, Wright CL, et al. Medications as a risk factor for fragility hip fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2020;107(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang C-M, Wu EC-H, Chang I-S, Lin K-M.. benzodiazepine and risk of hip fractures in older people: a nested case-control study in Taiwan. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(8):686–692. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817c6a99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacqmin-Gadda H, Fourrier A, Commenges D, Dartigues J-F.. Risk factors for fractures in the elderly. Epidemiology. 1998;9(4):417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Solmi M, Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, et al. Safety, tolerability, and risks associated with first-and second-generation antipsychotics: a state-of-the-art clinical review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:757–777. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S117321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kishimoto T, De Hert M, Carlson HE, Manu P, Correll CU.. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in people with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(5):415–429. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328355e1ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taipale H, Rysä J, Hukkanen J, et al. Long-term thiazide use and risk of low-energy fractures among persons with Alzheimer’s disease-nested case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(7):1481–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-04957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matthews R, Brill I.. SAS programs to select controls for matched case-control studies. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/. Accessed June 7, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kinon BJ, Gilmore JA, Liu H, Halbreich UM.. Prevalence of hyperprolactinemia in schizophrenic patients treated with conventional antipsychotic medications or risperidone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(2):55–68. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):939–951. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen JX, Su YA, Bian QT, et al. Adjunctive aripiprazole in the treatment of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;58:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taipale H, Solmi M, Lähteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, Tiihonen J.. Antipsychotic use and risk of breast cancer in women with schizophrenia: a nationwide nested case-control study in Finland. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(10):883–891. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanskanen A, Taipale H, Koponen M, et al. From prescription drug purchases to drug use periods—a second generation method (PRE2DUP). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clément-Lacroix P, Ormandy C, Lepescheux L, et al. Osteoblasts are a new target for prolactin: analysis of bone formation in prolactin receptor knockout mice**This work was supported in part by grants from Hoechst Marion Roussel, Inc. Endocrinology. 1999;140(1):96–105. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.1.6436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klibanski A, Neer RM, Beitins IZ, Ridgway EC, Zervas NT, McArthur JW.. Decreased bone density in hyperprolactinemic women. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(26):1511–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198012253032605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mazziotti G, Mancini T, Mormando M, et al. High prevalence of radiological vertebral fractures in women with prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. Pituitary. 2011;14(4):299–306. doi: 10.1007/s11102-011-0293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Solmi M, Veronese N, Correll CU, et al. Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and fractures among people with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(5):341–351. doi: 10.1111/acps.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schlechte JA, Sherman B, Martin R.. Bone density in amenorrheic women with and without hyperprolactinemia*. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56(6):1120–1123. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-6-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mazziotti G, Porcelli T, Mormando M, et al. Vertebral fractures in males with prolactinoma. Endocrine. 2011;39(3):288. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Nitta M, Kane JM, Correll CU.. Long-term effectiveness of oral second-generation antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of direct head-to-head comparisons. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):208–224. doi: 10.1002/wps.20632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kane JM, Agid O, Baldwin ML, et al. Clinical guidance on the identification and management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(2):18com12123. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18COM12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane JM.. Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it be avoided? J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):603–613. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12R08064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu Y, Zhang C, Siafis S, et al. Prolactin levels influenced by antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2021;237:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang L, Qi H, Xie Y-Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and paeoniae-glycyrrhiza decoction for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:728204. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.728204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li X, Tang Y, Wang C.. Adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70179–e70179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lodhi RJ, Masand S, Malik A, et al. Changes in biomarkers of bone turnover in an aripiprazole add-on or switching study. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, Vano L, et al. Comparative effects of 18 antipsychotics on metabolic function in patients with schizophrenia, predictors of metabolic dysregulation, and association with psychopathology: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):64–77. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30416-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):3–24. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15032SU1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, Kane J, Correll C.. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):387–404. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Correll C, Solmi M, Croatto G, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):248–271. doi: 10.1002/wps.20994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, De Hert M.. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421–453. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0157-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data collected for this study are proprietary of the Finnish government agencies Social Insurance Institution of Finland, National Institute for Health and Welfare, which granted researchers permission and access to the data. The data that support these findings of this study are available from these authorities, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The code used to analyze these data is available upon request from the corresponding author, for purposes of reproducing the results.