Abstract

Diabetes is rising at an alarming rate, as 1 in 10 adults worldwide now lives with the disease. In Qatar, a middle eastern Arab country, diabetes prevalence is equally concerning and is predicted to increase from 17% to 24% among individuals aged 45 and 54 years by 2050. While most healthcare strategies focus on preventative and improvement of in-hospital care of patients with diabetes, a notable paucity exists concerning diabetes in the prehospital setting should ideally be provided. This quality improvement study was conducted in a middle eastern ambulance service and aimed to reduce ambulance callbacks of patients with diabetes-related emergencies after refusing transport to the hospital at the first time. We used iterative four-stage problem-solving models. It focused on the education and training of both paramedics and patients. The study showed that while it was possible to reduce the rate of ambulance callbacks of patients with diabetes, this was short-lived and numbers increased again. The study demonstrated that improvements could be effective. Hence, changes that impacted policy, systems of care and ambulance protocols directed at managing and caring for patients with diabetes-related prehospital emergencies may be required to reify them.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Healthcare quality improvement, Prehospital care

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

According to the WHO, diabetes affects 442 million people worldwide. The prevalence rate and the number of diabetes-related emergencies, such as hypoglycaemia and diabetic coma, are gradually increasing. In an emergency, paramedics must transport patients to an appropriate healthcare facility once they are medically stabilised. However, some patients refuse hospital transport after receiving on-scene emergency treatment. Soon after, they call back with a similar complaint. This delays definitive medical care.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We demonstrated that providing adequate health education could reduce transport refusals, ambulance callbacks, and save resources. Thereby increasing the number of ambulances available to respond to other emergency calls.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Governmental (Hamad Medical Corporation Ambulance Service (HMCAS) and Hamad Medical Corporation Diabetes Center (HMC-DC)) and non-governmental (Qatar Diabetes Association (QDA)) organisations can complement each other in promoting better health, screening and disease prevention. This multisectoral approach is essential and creates a holistic patient experience.

Introduction

Diabetes is a global healthcare concern. According to the WHO, diabetes affects 442 million people worldwide, and it caused approximately 1.5 million deaths in 2019.1 Although it is a controllable chronic disease, its prevalence rate is nevertheless increasing with the number of diabetes-related emergencies, such as hypoglycaemia and diabetic coma, which can sometimes lead to a lethal outcome.2 3 In addition, research demonstrated that newly diagnosed patients with diabetes might suffer from depression, resulting in their unwillingness to access medical services.4–6 Most healthcare systems worldwide focus on managing in-hospital diabetic patients’ admissions7; little attention has been paid to prehospital emergency medical systems (EMS) that could control and help avoid diabetes-related complications. According to data on patients with diabetes in the US National Emergency Medical Services Information System database, in 2015, 13.9% of diabetes admissions in emergency departments were made by EMS.7 In Glasgow, Scotland, in 2019, around 40% of patients with diabetes attended to by ambulance services were referred to the hospital, and the callback rate was less than 5%.8 In another study in Scotland, 49.8% of patients with diabetes reported having had hyperglycaemic emergencies; further, treatment by paramedics in prehospital settings significantly helped manage it, reducing the conveyance to the hospital to around 39%.9 So far, no study has explored the non-conveyance of diabetes emergencies in prehospital settings in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

By 2050, diabetes prevalence is predicted to increase to 24% among individuals aged between 45 and 54 years in Qatar.10 11 The HMCAS delivers prehospital emergency medical care when individuals in Qatar call 999. Once patients are medically stabilised, paramedics must transport them to an appropriate healthcare facility.12 13 The HMCAS’ ambulance response times are short and consistent with international standards.14 Thus, some patients refuse transport to the hospital after receiving on-scene emergency treatment but call back 999 with a similar complaint soon after. This could delay definitive medical care. Patients and paramedics in Qatar might not speak the same first language, creating a specific gap in providing concise and accurate advice about diabetes education. Additionally, the patient may fear the long waiting hours in the emergency department,15 of which increase the odds of patients refusing transport to the hospital.

Effective communication with patients in prehospital settings is challenging for prehospital healthcare providers, primarily because they are unable to provide proper and consistent medical advice.16 In 2016, 43.37% (N=504) of patients with diabetes treated by HMCAS refused hospital transport after receiving initial emergency medical treatment.17

Health education provided by prehospital medical staff to patients with diabetes needed to be enhanced.18 Diabetes education is essential for self-management and positive health-related outcomes.19 Therefore, training HMCAS paramedics to provide appropriate diabetes education could reduce the patients’ 999 callback rates, thereby reducing the demand on HMCAS resources.

We conducted a quality improvement (QI) study aimed at reducing callbacks to 999 by patients with diabetes who refused transport to the hospital within 72 hours after receiving emergency treatment by HMCAS paramedics. We hypothesised that if HMCAS paramedics could provide appropriate diabetes education to patients, it would reduce the occurrence of diabetes-related emergencies and consequently reduce their callback rates within 72 hours. This study used Quality Control Tools (QCT) to demonstrate the implemented interventions’ impact, understand process behaviour and identify potential solutions.20

Methods

Context

This QI study was part of the Clinical Care Improvement Training Programme (CCITP)21 organised by the Hamad Healthcare Quality Institute. The CCITP is a 4-month programme that builds knowledge among the healthcare staff about healthcare QI tools. Participants from different departments attended workshop sessions with online assignments alongside the CCITP improvement coaches and faculty, who guided the participants in conducting a basic QI project in their respective departments.

The HMCAS Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) define hypoglycaemia as a random blood sugar level (RBS) <4 mmol/L. The maximum level of acceptable postprandial hyperglycaemia is 10 mmol/L.22 23 Thus, we excluded patients with RBS levels between four and 11 mmol/L. During the study period, 437 individuals with diabetes met the inclusion criteria. They received prehospital emergency care, declined hospital transport, but called back emergency services within 72 hours. Each patient was assigned a unique code in the online record system to conceal their personal information and protect their privacy.

This project hypothesised that delivering a good quality of health education to patients with diabetes who called 999 and were not conveyed to hospital helps reduce the incidence of callbacks made to 999 within a short period for the same issue. Further, four Plan–Do–Study–Act (PDSA) cycles were tested from 2017 to 2021. The PDSA approach is frequently used in healthcare as it helps conduct improvement projects in a structured manner to test the changes before implementation.24

The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence checklist was used for preparing this article.18 Minitab software V.17 was used for data analysis.

Interventions

We implemented several interventions for the paramedics working in Ambulance Service to equip them to deliver concise diabetic education in the prehospital setting. A future-state process map was produced (online supplemental appendix 1).

bmjoq-2022-002007supp001.pdf (322.9KB, pdf)

In the brainstorming sessions, multidisciplinary team members captured these ideas and developed an Ishikawa diagram, a standard Quality Tool (QT) used to record a problem’s causes.25

PDSA cycles were used to test the implemented interventions. The key goal was to reduce callbacks to 999 patients with diabetes who refused transport to the hospital within 72 hours after receiving emergency treatment by teaching HMCAS paramedics how to provide concise and consistent health education to all patients with diabetes. It was hypothesised that adequate knowledge given by HMCAS paramedics to such patients would reduce the onset of diabetes-related emergencies and thus reduce callbacks.

These implemented improvement interventions were spread over the following four phases:

PDSA 1

Plan

Improve the prerequisite paramedics’ knowledge to provide concise and consistent health education to patients with diabetes in prehospital settings.

Emphasise that the health education they provide is necessary to prevent life-threatening diabetic complications in patients who refuse transport to the hospital. As paramedics focus on attending to life-threatening situations, they may be unaware that providing appropriate health education also helps prevent life-threatening diabetes emergencies.

The interventions were conducted in HMCAS hubs 1, 2 and 4 in 2017.14 They represent 37.5% of HMCAS hubs and cover about 70% of Qatar’s population.

Do

A knowledge assessment survey was conducted to measure all HMCAS paramedics’ knowledge about diabetes health education.

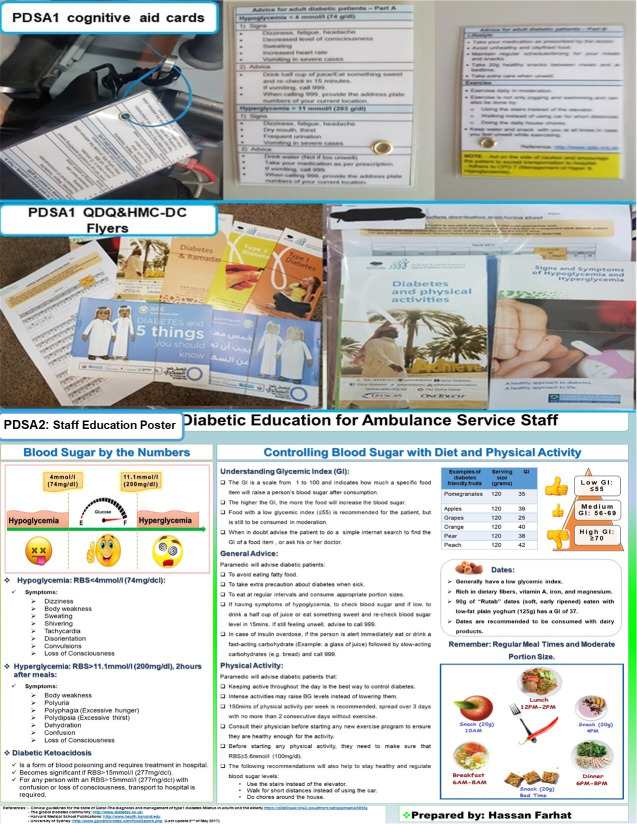

Cognitive Aid Cards (CAC) (figure 1) with educational content were prepared and attached to all portable patient monitors of the vehicles in these hubs (figure 1). The CAC contained educational content that was easy to understand and implement daily. For example, ‘Use stairs instead of elevators’, ‘Help with house chores, as a type of physical activity’, ‘Park their cars in distant locations at malls’, and ‘Eat their preferred food but in moderate quantity followed by exercise’. The HMC diabetes educators were consulted to determine the appropriateness of the content.

Between 21 April 2017 and 30 April 2017, in addition to the CAC pieces of advice, paramedics from the concerned hubs also distributed informative leaflets to all patients with diabetes who called 999 (figure 1). Governmental (HMC-DC) and non-governmental (QDA) organisations in Qatar supplied these leaflets (N=300).

Further, at least one improvement team member was present in the hubs included in this phase of the study at the change shift time at 5:00 and 17:00 hours each day between 13 April 2017 and 20 April 2017, to brief each staff about the interventions.

On 4 May 2017, a staff circular was disseminated to encourage paramedics to provide consistent and concise health education to all patients with diabetes treated in prehospital settings using the CAC and the leaflets.

Nine days later, another survey was conducted to determine whether the paramedics’ knowledge about diabetes education had improved.

The responses to both surveys were analysed. The daily numbers of patients with diabetes who called 999 for diabetes-related emergencies and refused transport were collected, along with the numbers of patients with diabetes who called back within 72 hours of refusing transport.

Figure 1.

PDSA phase 1 and 2 interventions. HMC-DC, Hamad Medical Corporation-Diabetes Center; PDSA, Plan–Do–Study–Act; QDA, Qatar Diabetes Association; RBS, random blood sugar.

Study

The impact of the interventions on the paramedics’ knowledge about education of patients with diabetes.

The impact of the interventions on reducing the number of patients with diabetes who called 999 back within 72 hours of refusing transport.

Act

Decide whether to sustain the interventions, adapt and retest or not.

PDSA 2

Plan

Between July 2017 and December 2018, sustain and reinforce the same plan of PDSA1.

Do

The CACs were attached to the portable patient monitors of all HMCAS emergency section ambulances.

An educational poster was created and displayed in all HMCAS hubs. It contained diabetes health information to be given by paramedics to every patient with diabetes who called 999 and received emergency treatment regardless of the type of complaint they called for (figure 1).

Study

The impact of the interventions on reducing the number of patients with diabetes who called back within 72 hours of refusing hospital transport initially.

Act

Decide whether to sustain the interventions, adapt and retest or not.

PDSA 3

Plan

At the beginning of 2018, sustain the interventions implemented in phases 1 and 2 with minor modifications.

Do

The project team suggested a modified version of the existing HMCAS diabetes CPG. It included motivational pieces of advice, health education information utilised in the CAC, and the staff educational poster from the previous PDSA cycles. They were suggested to be included as part of the emergency treatment the paramedics delivered.

Based on the demographic information in the previous PDSA cycles and literature review,26–29 the team suggested adding the Glucagon intramuscular injection as part of the emergency treatment of severe hypoglycaemia in the CPG. The rationale was to provide paramedics with more treatment options. Sometimes it might be difficult to find intravenous access for elderly patients, making it challenging to administer Dextrose 10% intravenously. Dextrose has been the emergency treatment for severe hypoglycaemia in the HMCAS and worldwide EMS.28 30 31

These suggestions were approved in 2019.

Study

The impact of the interventions on reducing the number of patients with diabetes who called back within 72 hours after refusing transport at first.

Act

Decide whether to sustain the interventions, adapt and retest or not.

PDSA 4

Plan

In 2020, sustain the outcome of the previous phases by refreshing the paramedics’ knowledge about the importance of diabetes health education.

Do

The team advised to include the outcome of this project in the 1-day continuous professional development (CPD) medical course delivered to HMCAS staff. All HMCAS paramedics (Ambulance Paramedics and Critical Care Paramedics) must attend the medical CPD course annually. It was conducted 49 times and was attended by 477 staff, despite an interruption between April and September 2020 during a peak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study

The impact of the intervention on reducing the number of patients with diabetes who called back within 72 hours after refusing transport at first.

Act

Decide whether to sustain the interventions, adapt and retest or not.

Measures and analysis

The weekly proportion of patients with diabetes who called back within 72 hours of receiving prehospital emergency treatment but refusing transport was monitored to measure the interventions’ impact.

Shewhart or Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts were generated to understand variations in the collected data. This chart is a statistical tool that aids clinical and administrative decisions when monitoring a process. It has been effective in statistically measuring healthcare output.32 33

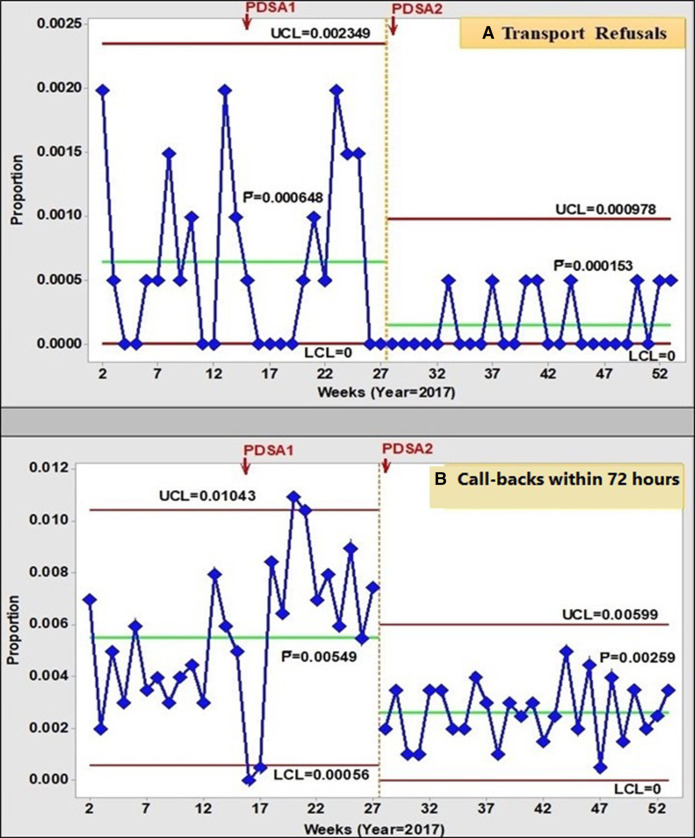

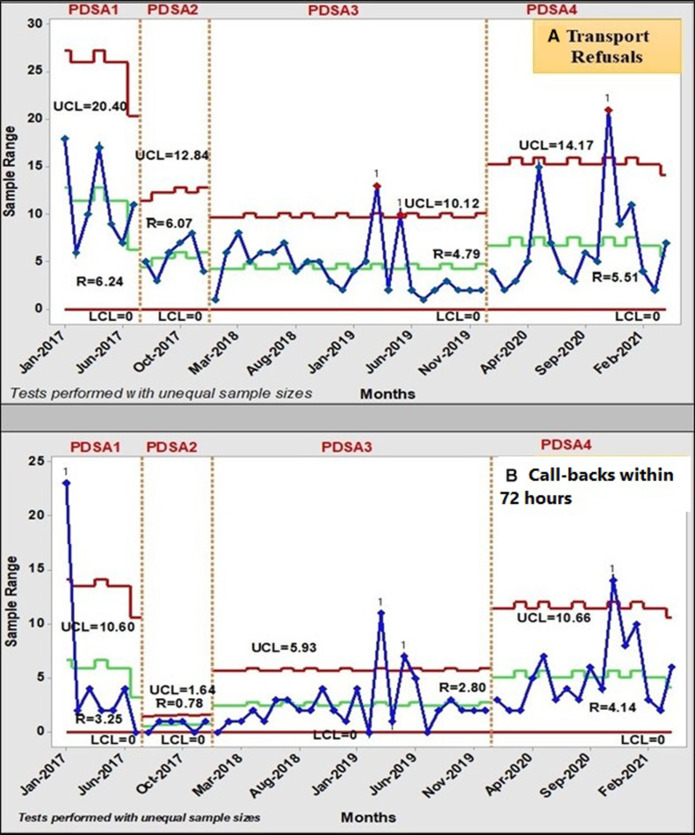

SPC P-charts (figure 3) were generated to display the weekly proportion of patients with diabetes who refused hospital transport and the proportion of callbacks within 72 hours for a similar complaint. SPC R-charts (figure 4) were produced to monitor the monthly number of patients with diabetes who refused transport and the monthly number of callbacks within 72 hours following transport refusal.

Results

From 1 January 2017 to 30 April 2021, the 999 HMCAS call centre received 1163 diabetes-related emergency calls. Callbacks occurred within 72 hours in 37.58% of cases (n=437). 87.7% (n=565; 52.27% females) of hospital transport refusal calls were hyperglycaemic emergencies, and 12.3% (n=79) were cases of hyperglycaemia.

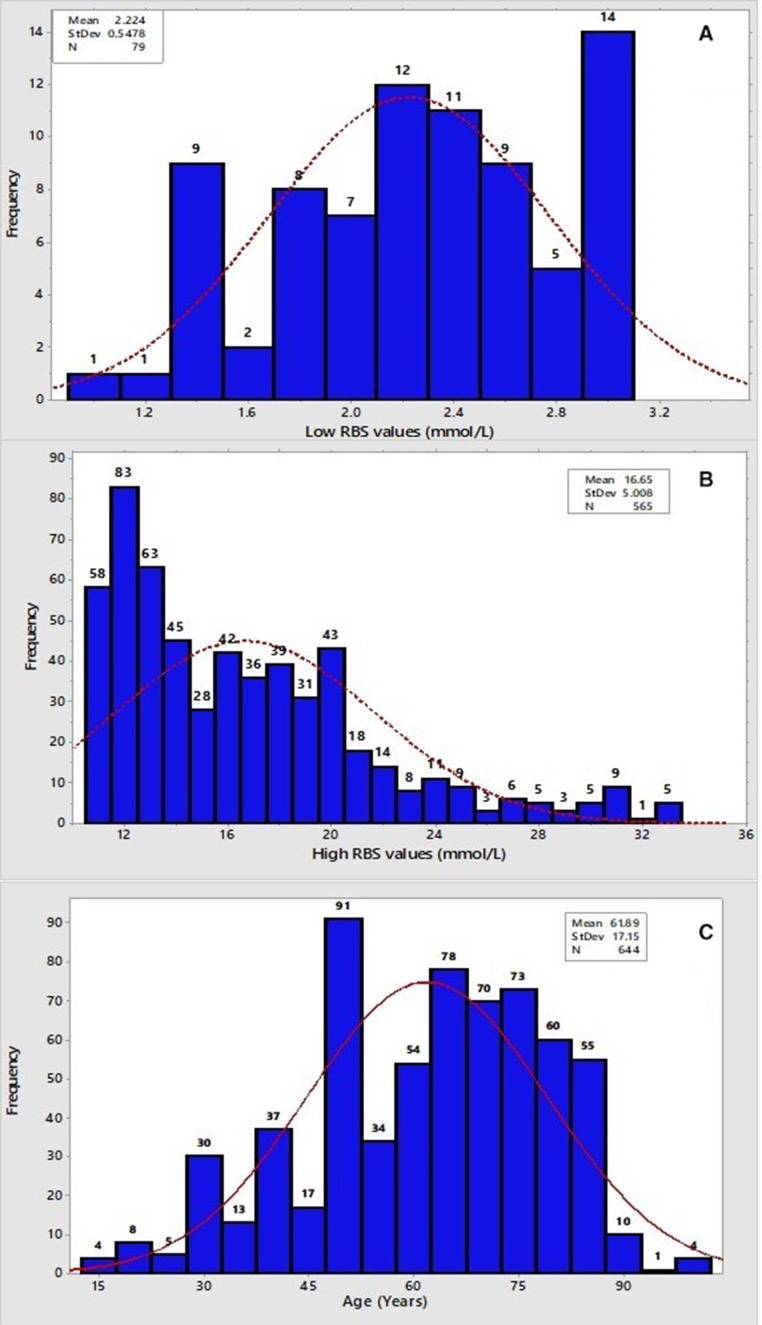

We created histograms of these data to investigate patients’ age and RBS level distribution (figure 2). The mean age of patients with diabetes who refused transport to the hospital was 61.89 years, with an SD equal to±17.15 (figure 2). The histogram was skewed to the right compared with the Gaussian distribution. This indicated that most of them were older than 61.89 years. For the RBS level distribution: in the low RBS level group, the mean RBS level was 2.22 mmol/L, with an SD equal to±0.54. Hence, the histogram was skewed to the right compared with the Gaussian distribution. This indicated that the number of patients with RBS levels <2.22 mmol/L was less than those with RBS levels between 2.22 mmol/L and 4 mmol/L. In the high RBS group, the mean RBS level was 16.65 mmol/L, with an SD equal to±5, with the histogram skewed to the left, indicating the number of patients with RBS levels between 12 mmol and 16.65 mmol was higher than those with RBS level >16.65 mmol/L.

Figure 2.

Random blood sugar (RBS: A and B) and age (C) histograms of patients who called 999 and refused transport to the hospital.

Figure 3 illustrates patient transport refusals. The process was stable before the interventions, which shifted before PDSA 2. In figure 3, callbacks were included, and a special cause was identified just before week 17 (below the lower control limit) with a significant drop in the proportion of patients with diabetes who called back 999 within 72 hours during the intervention. Between weeks 17 and 22, special causes were identified (above the upper control limit). Therefore, PDSA 1 and PDSA 2 were associated with a reduced proportion of weekly hospital transport refusals by patients with diabetes. The impact of PDSAs 1 and 2 on weekly callbacks by patients with diabetes within 72 hours of emergency medical attention was unclear, but a shift occurred shortly before PDSA 2 and was sustained during PDSA 2.

Figure 3.

Shewhart P-charts of all patients with diabetes weekly (A) transport refusals and (B) callbacks within 72 hours after transport refusals in 2017. PDSA, Plan–Do–Study–Act; UCL, Upper Control Limit; LCL, Lower Control Limit.

The project process was enhanced in PDSA 2 in 2017 and was sustained in 2018. After 2019, the transport refusal and callback rates increased proportionally (figure 4). Very few special cause variations were identified.

Figure 4.

Full study Shewhart R-bars charts of all patients with diabetes monthly (A) transport refusals and (B) callbacks within 72 hours after transport refusals. PDSA, Plan–Do–Study–Act; UCL: Upper Control Limit; LCL: Lower Control Limit.

Discussion

In the last decade, various countries, including the UK and the USA, acknowledged the importance of training paramedics in effective health education as they connect the healthcare system with the community.34 35 In the MENA region, providing health education in prehospital settings has rarely been considered, primarily because of financial constraints.36 37 In addition, social media has been identified as an essential resource to provide health education to patients with diabetes38; nonetheless, this was outside the scope of our study. Our collaboration with HMC-DC and QDA enabled us to use existing diabetic education leaflets that paramedics could distribute to the patients. We demonstrated the potential of improving cooperation between different healthcare agencies,39 and even between various departments within the same organisation.40 41

Some studies in the MENA region and Asia have discussed the importance of prehospital health education in reducing out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.42–44 However, to our knowledge, no study has examined prehospital healthcare workers’ ability to provide health education to patients with diabetes in prehospital emergency settings. Using the information provided to the paramedics in the CAC and the staff education poster, patients with diabetes were advised on how they could still eat their preferred foods while minimising their glycaemic index (GI) and food intake quantity. Paramedics were advised to use understandable terms to describe food quantity (eg, in ‘handfuls’ instead of grams) and their nutritional input according to patients’ GI.45 Additionally, recommending excessive physical activity could adversely affect the well-being of patients with diabetes46; thus, in this study, patients were advised to engage in moderate but regular physical activities.

Ethnicity is a contributing factor in type two diabetes.47 In our study, demographic information was only available for 644 patients who dialled 999 and refused hospital transport after receiving treatment, representing 58.23% of the study sample. Of these, 42.82% (n=276) were Qatari, 11.02% (n=71) were other Arabic nationalities, and the rest belonged to nine different nationalities (from South Asia, East Asia, Europe and America). This diversity makes providing concise health education to multilingual patients with diabetes challenging.48 49

We used QCT, including SPC charts, to monitor the interventions’ effects. Although SPC charts (figures 3 and 4) could not explain the variation in transport refusals and callbacks, histograms (figure 2) helped identify that most transport refusal patients were above 60 years of age. Diabetes self-management can be more challenging for this age group.50 In this study, most patients with diabetes, had a very low RBS level, sometimes less than two mmol/L, while others had a very high RBS level, sometimes greater than 20 mmol/L (figure 2). Therefore, suggesting adding in the CPG, the Glucagon intramuscular injection as part of the emergency treatment of severe hypoglycaemia was proven necessary. Using these histograms, decision-makers could conclude that prehospital education techniques for patients with diabetes should consider these factors. Further, SPC charts (figures 3 and 4) were used to monitor the interventions’ impact on reducing calls-back by patients with diabetes within 72 hours of refusing transport.

SPC charts are helpful and effective for monitoring processes and improvement efforts. They can clarify the variation within a process and differentiate between normal variation and special causes.51 We recalculated the control limits after 29 data points51 for the P-control charts (figure 3) to map with the PDSAs, and found that the proportion of refusals and callbacks by patients with diabetes was significantly reduced after two PDSA cycles. Both processes were stable and predictable. The SPC R-bar charts (figure 4) were better for observing variation over a long period with many data points. They demonstrated that these processes (refusals and callbacks of patients with diabetes) were unstable and unpredictable with the appearance of a few special variation causes after implementing PDSA 3. After implementing PDSA 4, the number of transport refusals and callbacks within 72 hours increased, and special causes appeared again, reflecting the unstable and unpredictable process. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected healthcare systems52 53 and most likely affected the previously observed improvements, as patients feared COVID-19 exposure at hospitals.54 The control charts in figure 4 indicate that the process started regaining stability in early 2021. Further monitoring is required to determine the current state and establish the need for another PDSA cycle.33 54

Limitations

First, most project team members were new to healthcare QI tools initially. CCITP training aimed to teach healthcare professionals how to use essential QI tools through small interventions in their departments in a subject they chose. Thus, this study’s primary team was new to the QI field and was only later reinforced with QI experts at the start of PDSA 4. A more experienced team may have approached aspects of this project differently and collected more demographic data. Second, demographic diversity, representing multiple languages and levels of health education awareness, challenged the development of patient education material.55 Third, the project relied on secondary data; hence some data were missing. Fourth, the pressure of the increased emergency calls managed by HMCAS (from 177 628 calls in 2016 to 268 953 in 2020) may have affected the quality of health education provided by the staff, which may explain why the improvement was seemingly not sustained. These limitations contributed to our inability to stratify the control charts by gender or blood sugar level groups and enable further process analysis.

Conclusion

Prehospital emergency medical services have a finite capacity; hence, patient callbacks put additional pressure on resources, may delay definitive care and could result in adverse health outcomes. Through this study, we reduced the callback rate of patients with diabetes who refused hospital transport but called back within 72 hours following two PDSA cycles. However, this was not sustained, as the analysis did not account for the gradual increase in emergency calls. This study demonstrated that providing adequate health education could reduce emergency callbacks and save resources to respond to other emergency calls. The multisectoral coordination between the HMCAS, the HMC-DC and the QDA was fruitful and helped create a holistic patient experience. Further cooperation between prehospital and in-hospital emergency medical services and other institutions may enhance health education and ensure access to effective patient care.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our deep gratitude to the HMCAS executive team for their support. Thanks to the Qatar Diabetes Association and the HMC Diabetes Center, particularly Dr. Manal Musallam Othman, for her unlimited support. Thanks to all the HMCAS staff who were motivated to support the study’s interventions. Thanks to the HMCAS Business Intelligence team and the HMCAS Training Department instructors.

Open Access funding is provided by Qatar National Library.

Footnotes

Contributors: HF conceptualised the project, performed the data analysis and prepared the manuscript and the guarantor. KEA and RR validated the data and reviewed the manuscript. KA, PG and MCK reviewed the manuscript. JL and GA, and LAS, supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: Open Access funding is provided by Qatar National Library.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available with the first author and can be provided on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This project was approved by the HHQI faculty and the HMCAS executive team.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Report of the global diabetes Summit, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2021/04/14/default-calendar/global-diabetes-summit

- 2.Minisry of Public Health . Q. Qatar national diabetes Strategy-Preventing diabetes together 2016 – 2022. Qatar: Ministry of Public Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, et al. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia 2019;62:3–16. 10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seiffge-Krenke I. Diabetic adolescents and their families: stress, coping, and adaptation. Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt RIG, de Groot M, Golden SH. Diabetes and depression. Curr Diab Rep 2014;14:491. 10.1007/s11892-014-0491-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nouwen A, Adriaanse MC, van Dam K, et al. Longitudinal associations between depression and diabetes complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2019;36:1562–72. 10.1111/dme.14054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benoit SR, Kahn HS, Geller AI, et al. Diabetes-related emergency medical service activations in 23 states, United States 2015. Prehosp Emerg Care 2018;22:705–12. 10.1080/10903127.2018.1456582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bloomer K. A retrospective cross-sectional analysis of re-contact rates and clinical characteristics in diabetic patients referred by paramedics to a community diabetes service following a hypoglycaemic episode. Br Paramed J 2021;6:1–9. 10.29045/14784726.2021.9.6.2.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villani M, Earnest A, Smith K, et al. Outcomes of people with severe hypoglycaemia requiring prehospital emergency medical services management: a prospective study. Diabetologia 2019;62:1868–79. 10.1007/s00125-019-4933-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Thani MH, Al-Thani AAM, Cheema S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of metabolic syndrome in Qatar: results from a national health survey. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009514. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awad SF, O'Flaherty M, Critchley J, et al. Forecasting the burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Qatar to 2050: a novel modeling approach. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;137:100–8. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farhat H, Gangaram P, Castle N, et al. Hazardous materials and CBRN incidents: fundamentals of pre-hospital readiness in the state of Qatar. J Emerg Med Trauma Acute Care 2021;2021. 10.5339/jemtac.2021.qhc.35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farhat H, Laughton J, Gangaram P, et al. Hazardous material and chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear incident readiness among prehospital care professionals in the state of Qatar. Glob Secur Health, Sci Policy 2022;7:24–36. 10.1080/23779497.2022.2069142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alinier G, Wilson P, Reimann T. Influential factors on urban and rural response times for emergency ambulances in Qatar. Mediterr J Emerg Med 2018:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King R, Oprescu F, Lord B, et al. Patient experience of non-conveyance following emergency ambulance service response: a scoping review of the literature. Australas Emerg Care 2021;24:210–23. 10.1016/j.auec.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross LJ, Jennings PA, Gosling CM, et al. Experiential education enhancing paramedic perspective and interpersonal communication with older patients: a controlled study. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:239. 10.1186/s12909-018-1341-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farhat H. Tackling diabetic patients 999 recalls through health education by hamad medical corporation-ambulance service staff. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2019;12:74–94. 10.4103/JETS.JETS_1_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapostolle F, Hamdi N, Barghout M, et al. Diabetes education of patients and their entourage: out-of-hospital national study (educated 2). Acta Diabetol 2017;54:353–60. 10.1007/s00592-016-0950-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerard SO, Griffin MQ, Fitzpatrick J. Advancing quality diabetes education through evidence and innovation. J Nurs Care Qual 2010;25:160–7. 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3181bff4fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh AP. Quality improvement using statistical process control tools in glass bottles manufacturing company. Int J Qual Res 2013;17:20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suliman S, Hassan R, Athamneh K, et al. Blended learning in quality improvement training for healthcare professionals in Qatar. Int J Med Educ 2018;9:55–6. 10.5116/ijme.5a80.3d88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haldeman-Englert C. Two-Hour Postprandial Glucose - Health Encyclopedia - University of Rochester Medical Center; 2021.

- 23.Weatherspoon D. Blood sugar chart: target levels throughout the day; 2019.

- 24.Coury J, Schneider JL, Rivelli JS, et al. Applying the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) approach to a large pragmatic study involving safety net clinics. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:411. 10.1186/s12913-017-2364-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabry A, Habashy M, Nageeb A, et al. How to use quality tools to prevent adverse drug reactions in hospitals? Medicine Updates 2022;8:123–39. 10.21608/muj.2021.100162.1075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sibley T, Jacobsen R, Salomone J. Successful administration of intranasal glucagon in the out-of-hospital environment. Prehosp Emerg Care 2013;17:98–102. 10.3109/10903127.2012.717171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabbay RA, Kahn PA, Wagner NE. Underutilization of glucagon in the prehospital setting. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:427–8. 10.7326/L18-0300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostykus P, Kennel J, Adair K, et al. Variability in the treatment of prehospital hypoglycemia: a structured review of EMS protocols in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care 2016;20:524–30. 10.3109/10903127.2015.1128031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe BH, Singh M, Villa-Roel C, et al. Acute management and outcomes of patients with diabetes mellitus presenting to Canadian emergency departments with hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes 2015;39:55–64. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hern HG, Kiefer M, Louie D, et al. D10 in the treatment of prehospital hypoglycemia: a 24 month observational cohort study. Prehosp Emerg Care 2017;21:63–7. 10.1080/10903127.2016.1189637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanello A, Gausche-Hill M, Mulkerin W, et al. Altered mental status: current evidence-based recommendations for prehospital care. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:527–41. 10.5811/westjem.2018.1.36559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broughton J, Anderson TR. Use of control charts to monitor groundwater quality for mining operations. AusIMM Bull 2017;80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langley GJ. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organisational performance. Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booker M, Voss S. Models of paramedic involvement in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:477–8. 10.3399/bjgp19X705605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cash RE, Clay CE, Leggio WJ, et al. Geographic distribution of accredited paramedic education programs in the United States. Prehosp Emerg Care 2021;0:1–9. 10.1080/10903127.2020.1856984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emara N, Mohieldin M. Financial inclusion and extreme poverty in the mena region: a gap analysis approach. REPS 2020;5:207–30. 10.1108/REPS-03-2020-0041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emara N, Rojas Cama F. Sectoral analysis of financial inclusion on gross capital formation: the case of selected Mena countries; 2020.

- 38.Alanzi T. Role of social media in diabetes management in the middle East region: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e9190. 10.2196/jmir.9190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biermann R, Koops JA, Koops JA. Studying Relations Among International Organizations in World Politics: Core Concepts and Challenges. In: Koops JA, Biermann R, eds. Palgrave Handbook of Inter-Organizational relations in world politics. UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aswad WOSJ, Damayanti M. Multi-stakeholder collaboration for the provision of public open space (case of Taman Indonesia Kaya, Semarang). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2020;409:12053. 10.1088/1755-1315/409/1/012053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Øverbye E, Smith RSN, Karjalainen V. The Coordination Challenge. In: Rescaling social policies: towards multilevel governance in Europe. Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berhanu A. A profile of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in northern Emirates, United Arab Emirates. Saudi Med J 2017;38:666–8. 10.15537/smj.2017.6.20128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamouda C, Somrani N. Gathering medicine: prehospital emergencies among Tunisian pilgrims to Mecca. Emerg Med 2018;08. 10.4172/2165-7548.1000373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yee LS, Khalid K, Abidin IZZ. Mortality patterns in the emergency and trauma department, hospital Tuanku Fauziah, Perlis: a three-year retrospective analysis: ETD mortality patterns in hospital Tuanku Fauziah. Malays J Emerg Med 2018;3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Livesey G, Taylor R, Livesey HF, et al. Dietary glycemic index and load and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and updated meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients 2019;11:1280. 10.3390/nu11061280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colberg SR. Key points from the updated guidelines on exercise and diabetes. Front Endocrinol 2017;8:33. 10.3389/fendo.2017.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al Busaidi N, Shanmugam P, Manoharan D. Diabetes in the middle East: government health care policies and strategies that address the growing diabetes prevalence in the middle East. Curr Diab Rep 2019;19:8. 10.1007/s11892-019-1125-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galeshi R, Sharman J, Cai J. Influence of ethnicity, gender, and immigration status on millennials’ behavior related to seeking health information. EDI 2018;37:621–31. 10.1108/EDI-05-2017-0102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Obinna DN. Confronting disparities: race, ethnicity, and immigrant status as intersectional determinants in the COVID-19 era. Health Educ Behav 2021;48:397–403. 10.1177/10901981211011581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suhl E, Bonsignore P. Diabetes self-management education for older adults: general principles and practical application. Diabetes Spectr 2006;19:234–40. 10.2337/diaspect.19.4.234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Provost PL, Murray SK. The health care data guide: learning from data for improvement. Wiley, 2011. www.josseybass.com [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khetrapal S, Bhatia R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health system & sustainable development Goal 3. Indian J Med Res 2020;151:395. 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1920_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alsoufi A, Alsuyihili A, Msherghi A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: medical students' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS One 2020;15:e0242905. 10.1371/journal.pone.0242905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:e10–11. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al Muftah H. Demographic Policies and Human Capital Challenges. In: Tok ME, Alkhater LRM, Pal LA, eds. Policy-Making in a transformative state: the case of Qatar. UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016: 271–94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2022-002007supp001.pdf (322.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data are available with the first author and can be provided on reasonable request.