Abstract

Cardiac troponin C (cTnC) is the critical Ca2+ sensing component of the troponin complex. Binding of Ca2+ to cTnC triggers a cascade of conformational changes within the myofilament that culminate in force production. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) associated TNNC1 variants generally induce a greater degree and duration of Ca2+ binding, which may underly the hypertrophic phenotype. Regulation of contraction has long been thought to occur exclusively through Ca2+ binding to site II of cTnC. However, work by several groups including ours, suggest that Mg2+, which is several orders of magnitude more abundant in the cell than Ca2+ may compete for binding to the same cTnC regulatory site.

We previously used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to demonstrate that physiological concentrations of Mg2+ may decrease site II Ca2+-binding in both N-terminal and full length cTnC. Here, we explore the binding of Ca2+ and Mg2+ to cTnC harbouring a series of TNNC1 variants thought to be causal in HCM. ITC and thermodynamic integration (TI) simulations show that A8V, L29Q, and A31S elevate the affinity for both Ca2+ and Mg2+. Further, L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y that are adjacent to the EF hand binding motif of site II have a more significant effect on affinity and the thermodynamics of the binding interaction.

To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to explore the role of Mg2+ in modifying the Ca2+ affinity of cTnC mutations linked to HCM. Our results indicate a physiologically significant role for cellular Mg2+ both at baseline and when elevated on modifying the Ca2+ binding properties of cTnC and the subsequent conformational changes which precede cardiac contraction.

Keywords: Contractility, Myofilament, ITC, Calorimetry, MD Simulation, Thermodynamic Integration, Molecular Dynamics

Introduction

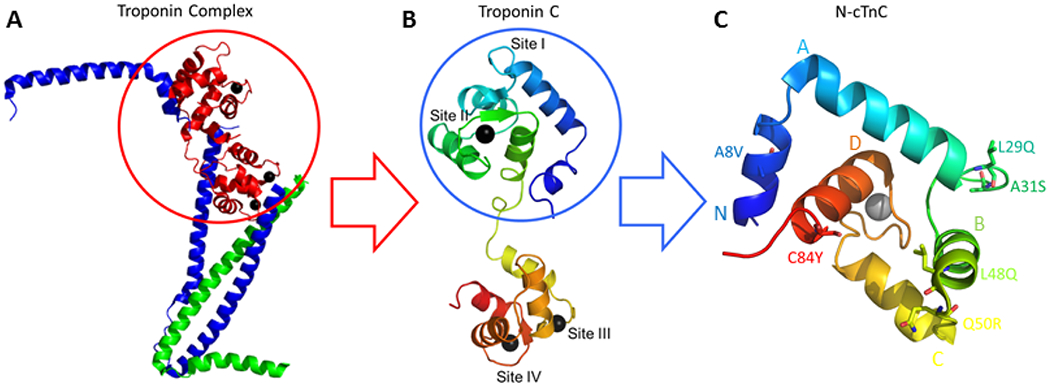

Cardiac troponin C (cTnC) is a dumbbell-shaped protein with 4 EF hand domains. High affinity structural sites III and IV in the C-terminal domain bind Ca2+ (KA ~ 107 M−1) and Mg2+ (KA ~104 M−1) to tether cTnC to the other components of the cardiac troponin (cTn) complex [1–3]. The N-terminal domain contains site I (which is dysfunctional in cardiac muscle) and site II which plays the critical regulatory role. Low affinity (KA ~105 M−1) site II binds Ca2+ at elevated concentrations during systole (400 – 1000 nM) and is largely unbound during diastole (100 nM) [4]. cTnC is composed of nine α-helices: helices N, A, B, C, and D in the N terminal-domain are linked through the flexible D-E linker to the C-domain which contains helices E, F, G, and H. Binding of Ca2+ to site II acts as a conformational switch, causing helices N, A and D to move away from helices B and C and expose a hydrophobic cleft (Figure 1). This region is then bound by the cTnI switch peptide (TnIsw), causing further perturbation within the cTn complex and the rest of the thin filament (TF) to expose actin binding sites allowing for contact with myosin heads, ultimately resulting in force production [5–7].

Figure 1:

N-cTnC within cTnC and the Troponin complex. A; the cTn complex is shown containing the core domain with some components excluded from the final protein structure to facilitate x-ray crystallography [108]. This complex includes the Ca2+ binding cTnC in red, the inhibitory cTnI in blue, and the tropomyosin binding cTnT in green. Black spheres depict the bound cations that interact with sites III/IV in the C-terminal domain and site II in the N-terminal domain. B; cTnC shown in rainbow colors with the N-terminal domain in blue and the C-terminal domain in red. C; the N-domain of cTnC (N-cTnC) with 6 mutations of interest labelled. Helices N through D are labelled. For this figure, PyMol was used to generate the cTnC structures.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) afflicts ~1 in 200 in the general population [8, 9]. Over 1,000 HCM-associated mutations have been found in a variety of sarcomeric proteins, of which over 100 are located in the cTn complex [10–13]. Despite a wide range of molecular precursors, the disease phenotype consistently entails hypertrophy, myocyte disarray, and fibrosis [14, 15]. This devastating disease often manifests as sudden cardiac arrest secondary to ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation and is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes [16, 17].

Hypertrophy has been posited to result from increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity which prolongs systole and shortens diastole [4]. Alternatively, hypertrophy may result from changes in maximum tension enacted by changes in tropomyosin displacement [18]. The role of cTnC as the Ca2+-sensing component has made it a target of study with multiple HCM-associated mutations identified in the regulatory N-terminal domain [19, 20]. While large scale studies show a sparce number of pathogenic HCM associated mutations in cTnC [21–24], this may be due to the central role this molecule plays in excitation-contraction (EC) coupling, whereby significant functional changes may be incompatible with physiological viability.

After potassium, Mg2+ is the second most abundant cellular cation with a total concentration of ~15 - 20 mM. Mg2+ is also tightly regulated through extensive buffering by cytosolic components such as ATP. A wide range of free Mg2+ concentrations between 0.2 – 3.5 mM have been reported in different systems with the majority of Mg2+ believed to exist in complex with ATP. The consensus is the free [Mg2+]i is ~0.5 - 1 mM making this cation approximately 3 orders of magnitude more abundant than systolic Ca2+ [25–27]. Short term ischemia (~15 minutes) elevates free Mg2+ up to 10-fold due primarily to a loss of [ATP]i [28, 29]. Studies on isolated TnC [30–35], the cTn complex [30, 32], and reconstituted fibers [32, 36] have demonstrated that Mg2+ decreases the ability of Ca2+ to expose the hydrophobic cleft and cause subsequent structural changes in the rest of the cTn complex. Previous studies utilizing physiological systems similarly demonstrated an inverse correlation between Ca2+ sensitivity of force production and availability of Mg2+ in skinned skeletal and cardiac fibers [37–39]. 3 mM Mg2+ decreased the Ca2+ affinity in isolated cTnC [3] and skinned psoas muscles [40], but did not seem to cause structural changes in cTnC [3, 41].

Equilibrium dialysis studies suggested that Mg2+ does not compete with Ca2+ for binding to the N-terminal cTnC, and exclusively binds to the two C-terminal sites [42]. This notion has endured for decades. In the time since, however, several studies have shown through a number of different experimental techniques that the Mg2+ binding affinity of site II of skeletal and cardiac TnC is physiologically relevant [31, 33, 39, 43–49]. The Mg2+ affinity of site II was estimated through fluorescence to have a KA of ~0.6 ×103 M−1 and through competition experiments, site II was posited to be 33 – 44% saturated with this cation at diastolic concentrations of Ca2+ [3]. More recent studies show that these results also hold in TnC variants of similar sequence from other species where Mg2+ binding affinity of is an order of magnitude lower than Ca2+ [50]. Our recently published ITC and thermodynamic integration simulations corroborated and expanded upon these same findings [51].

A prevalent idea posits that contractile protein variants which destabilize the closed conformation of the protein prior to Ca2+ binding and/or those that favor the open, Ca2+-bound state confer an increase in affinity [24]. Sequence variations outside the coordinating residues of the cTnC EF hands may induce alterations in Ca2+ affinity allosterically [52, 53]. These changes in Ca2+ binding have previously been linked to HCM and DCM-associated variants [41, 54, 55]. In contrast, variants outside the binding residues of each EF hand are not thought to allosterically modify Mg2+ binding [56–58], therefore the role of this cation in HCM is currently unclear. Here, we further explore the effects of Mg2+ on Ca2+ binding to the regulatory domain of cTnC and possible modifying affects on the previously listed series of HCM-associated variants.

In this study, we focus on the HCM associated TNNC1 variants A8V [59, 60], L29Q [61], A31S [62], and C84Y [63, 64], the engineered mutation L48Q [3] and the Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) -associated TNNC1 variant Q50R [65] (Figure 1). We have previously studied this series of mutations through Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations [55]. Our findings supported the notion that L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y destabilize the closed-state of cTnC or stabilize the interaction with the TnISW in the open-state leading to an increase in Ca2+-binding affinity. In contrast, A8V, L29Q, and A31S were found to alter Ca2+-coordination through a more subtle local structural perturbations [55].

We previously used ITC and thermodynamic integration (TI) simulations to show that physiological concentrations (1 mM) of free Mg 2+ significantly reduce Ca2+-binding to site II in both full-length and N-terminal cTnC [51]. It is important to establish whether cardiomyopathy mutations affect binding of Ca2+, Mg2+, or both. If the binding of these ions is affected unequally by a specific variant, then this could exacerbate or attenuate the effect when considering Ca2+ alone. This study compares Mg2+-induced modifications in the Ca2+ binding properties of the regulatory site of cTnC with cardiomyopathy associated TNNC1 variants with Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding affinity shown to be different for each mutant. In particular, the affect of L48Q on the binding of these cations was significantly different from the WT, with Q50R and C84Y also showing some small, insignificant differences. These findings underline the importance of considering background Mg2+ levels which were studied through competition experiments. We show that affinity of the five HCM-associated variants (including L48Q which is engineered) and a single DCM associated TNNC1 variant for Mg2+ is higher than WT cTnC which is now established to have a physiological significant affinity for Mg2+. Therefore, the presence of baseline Mg2+ may contribute to the dynamics which govern cardiac EC coupling. Further, higher than baseline concentrations of Mg2+ such as may occur during ischemia may accentuate the effects of inherited TNNC1 variants and further exacerbate dysfunction in the diseased heart.

Results

Each N-cTnC construct was independently titrated by Ca2+ and Mg2+ in the apo-state. Each construct was also independently pre-incubated with 1 mM Mg2+ and 3 mM Mg2+ and titrated by Ca2+ to measure the relative binding affinity (Figures 2 – 7).

Figure 2:

The thermodynamic properties of the binding interactions with WT N-cTnC and each of the mutants are listed. The Ca2+ and Mg2+ experiments were the titration of each cation into apo-state protein while +1/3 mM Mg2+ indicates the concentration of Mg2+ in each sample cell prior to titration with Ca2+. Each parameter is displayed the as mean ± SEM, with the exception of N which was fixed to 1.00 in the Mg2+ binding and preincubation experiments. ANOVA and subsequently Tukey’s test were independently used to find difference across constructs for each parameter and titration. For each parameter, the mean of constructs not connected by the same letter were found to be statistically different, p<0.05.

Figure 7:

Representative isotherms for each titration condition for L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y N-cTnC. In the 3 most N-terminal mutations are shown; L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y from top to bottom. On the left most panel, titration of Ca2+ into apo-state protein is shown with the next panels showing the titration of Ca2+ into 1 mM and 3 mM Mg2+ pre-incubated N-cTnC. The right most panel show the titration of Mg2+ into apo-state N-cTnC. These three mutants caused the greatest deviation in thermodynamic properties form the WT titration conditions. The Ca2+ into apo-protein titration is endothermic for Q50R and C84Y but exothermic for L48Q. The Mg2+ into apo-protein titration is endothermic for all 3 mutants. The pre-incubation condition with both 1 mM and 3 mM Mg2+ resulted in an exothermic interaction with Ca2+.

All studied TNNC1 variants increased the binding affinity of both Ca2+ and Mg2+ relative to the WT construct (Figure 2). The smallest increase was associated with A8V and the greatest with L48Q. In general, the mutations adjacent to site II (L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y) increased the affinity for each cation to a greater extent and altered the thermodynamic profile of the binding interaction more dramatically; the changes associated with the other mutants were more subtle.

The KA associated with Mg2+ binding was orders of magnitude lower than that determined for Ca2+ binding for all constructs (Figures 2 and 3). The addition of 1 mM Mg2+ decreased both the amount of binding and affinity for Ca2+ at site II with 3 mM Mg2+ further accentuating the trend (Table 1).

Figure 3:

Comparing the affinity for Ca2+/Mg2+ in each titration condition between all N-cTnC constructs. The x-axis labels indicate the tiration conditions: “Ca2+” indicates the titration of this cation into apo-state protein, similarly “Mg2+” indicates titration into apo-state protein. “+1 mM Mg2+” and “+3 mM Mg2+” are the pre-incubation conditions for the construct into which Ca2+ was titrated; the affinity obtained is therefore seen in a sytem with both Ca2+ and Mg2+ present. SEM error bars are used to depict where significant differences exist in the mean values. Sample size for each condition was between 6-9 independent tirations. With the exception of L48Q, the highest affinity is seen in the Ca2+ titration and the lowest in the Mg2+ titrations. L48Q has the highest Mg2+ binding affinity by over an order of magnitude. Increasing Mg2+ from 0 to 1 to 3 mM lowered Ca2+ binding affinity in a graded manner. ANOVA and subsequent Tukey’s post-hoc test indicate a number of differences in the mean KA between the constructs and titration conditions. For the titrations Ca2+ in the apo-state, L48Q, C84Y, and Q50R were significantly different from the WT. For the Mg2+ titrations in the apo-state, L48Q was significantly different from the WT. For pre-incubation with 1 mM Mg2+, A31S, L48Q, and C84Y were significantly different from the WT. For pre-incubations with 3 mM Mg2+ L48Q was significantly different form the WT.

Table 1 –

Mg2+ restraint distances for thermodynamic integration

| WT N-cTnC | L48Q | Q50R | C84Y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restraint 1 | ASP67 CG Atom 1029 |

2.3 Å | ASP67 CG Atom 1027 |

2.3 Å | ASP67 CG Atom 1036 |

2.3 Å | ASP67 CG Atom 1029 |

2.3 Å |

| Restraint 2 | SER69 OG Atom 1048 |

3.7 Å | SER69 OG Atom 1046 |

3.7 Å | SER69 OG Atom 1055 |

3.7 Å | SER69 OG Atom 1048 |

3.7 Å |

| Restraint 3 | THR71 OG1 Atom 1067 |

4.5 Å | THR71 OG1 Atom 1065 |

4.5 Å | THR71 OG1 Atom 1074 |

4.5 Å | THR71 OG1 Atom 1067 |

4.5 Å |

Ca2+ Binding

The interaction of Ca2+ with each construct was endothermic and entropically driven with the exception of L48Q in which the reaction was exothermic. Ca2+ bound to WT N-cTnC with a KA of 64.5 ± 3.1×103 M−1, A8V had moderately higher binding affinity. Relative to WT N-cTnC, Ca2+ bound to each cTnC variant with higher affinity: L29Q and A31S (~2-fold), L48Q (~6-fold), Q50R (~3.5-fold), and C84Y (~4-fold). The ΔG reflects the ΔH and the ΔS and as such demonstrates that the most favorable interaction occurs in L48Q, then Q50R/C84Y, followed by the other mutants (Figures 2, 8, 9). These results are in agreement with our previously published work [51, 55].

Figure 8:

Comparing the enthalpy for each Ca2+/Mg2+ titration condition between all N-cTnC constructs. Ca2+ and Mg2+ experiements are titration of each cation into apo-state protein while +1/3 mM Mg2+ indicates the concentration of Mg2+ in each sample cell prior to titration with Ca2+. SEM error bars are used to depict where significant differences exist in the mean values. Sample size for each condition was between 6-9 independent tirations. ANOVA and subsequent Tukey’s post-hoc test indicate a number of differences in the mean ΔH between the constructs and titration conditions. For the titrations Ca2+ in the apo-state, A31S>Q50R>C84Y>>L48Q were significantly different from the WT. For the Mg2+ titrations in the apo-state, only L48Q was significantly different from the WT. For pre-incubation with 1 and 3 mM Mg2+, all mutants were significantly different from the WT with A8V/L29Q most similar and L48Q most dissimilar from the WT.

Figure 9:

Comparing the entropy for each Ca2+/Mg2+ titration condition between all N-cTnC constructs. Ca2+ and Mg2+ experiements are titration of each cation into apo-state protein while +1/3 mM Mg2+ indicates the concentration of Mg2+ in each sample cell prior to titration with Ca2+. SEM error bars are used to depict where significant differences exist in the mean values. Sample size for each condition was between 6-9 independent tirations. ANOVA and subsequent Tukey’s post-hoc test indicate a number of differences in the mean T*ΔS between the constructs and titration conditions. For the titrations Ca2+ in the apo-state, A31S>Q50R>C84Y>>L48Q were significantly different from the WT. For the Mg2+ titrations in the apo-state, all conditions were significantly different and less than the WT. For pre-incubation with 1 and 3 mM Mg2+, all titrations were significantly different and less than the WT.

Mg2+ Binding

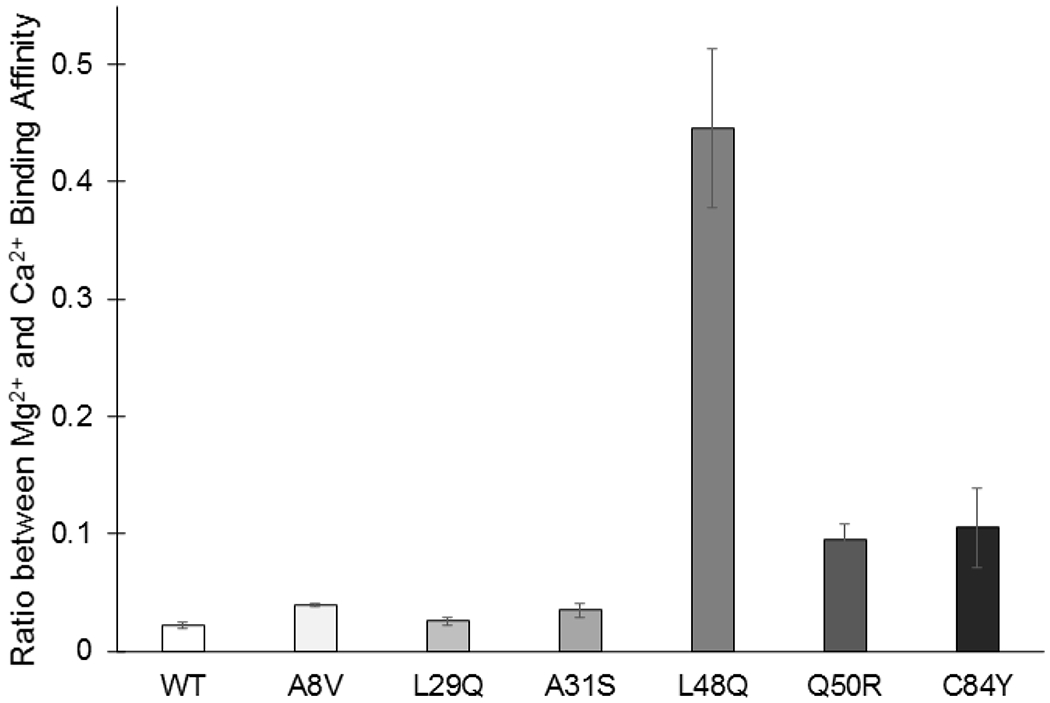

The interaction of Mg2+ with WT N-cTnC was endothermic and entropically driven with a KA of 1.4 ± 0.1 ×103 M−1; more than an order of magnitude lower binding affinity than seen with Ca2+. Relative to the WT, Mg2+ binding to each mutant occurred in a similar energetic profile and with higher affinity: A8V and L29Q (~2-fold), A31S (~3-fold), L48Q (~120-fold), Q50R (~15-fold), and C84Y (~20-fold) (Figure 2). The ratio between Mg2+ and Ca2+ binding affinity was significantly greater than seen in the WT in L48Q and greater but not significantly so in Q50R and C84Y; these findings stress the need for competition experiments which allow for the study of Ca2+-affinities in the presence of physiologically relevant Mg2+ concentrations (Figure 10).

Figure 10:

Ratio between Mg2+ and Ca2+ binding affinity for each N-cTnC construct indicating the realtive change in affinity. Standard deviation error bars are also depicted to provide a measure of the confidence in each ratio. Sample size for each set of titrations for the constructs was between 6-9. A greater ratio indicates that the Mg2+-binding affinity was greater in the construct relative to the baseline Ca2+-binding affinity. ANOVA and subsequent Tukey’s post-hoc test indicated that L48Q was significantly different from the other constructs, p<0.05 with the other constructs not statistically distinguishable. The ratio is not equal to one in any of the constructs highlighting the importance of considering background cellular Mg2+ in these studies and stressing the importance of competition experiments.

Ca2+ and Mg2+ Competitive Binding

Pre-incubation of WT N-cTnC with 1 mM Mg2+ lowered Ca2+-binding affinity by 1.6-fold and 3 mM Mg2+ further accentuated the effect. Pre-incubation of A8V with 1 and 3 mM Mg2+ reduced the Ca2+ affinity ~3 and 7-fold, respectively and in L29Q the change was ~3 and 9-fold, respectively. 1 and 3 mM Mg2+ decreased the Ca2+-affinity of L48Q by ~2 and 5-fold, respectively. Competition altered the reaction kinetics in A31S, Q50R, and C84Y making each interaction exothermic and enthalpically driven. In A31S 1 mM had a higher than apo-state affinity for Ca2+ (1.4-fold) yet 3 mM Mg2+ reduced Ca2+-binding affinity (~2-fold). In both Q50R and C84Y N-cTnC, 1 and 3 mM Mg2+ lowered the Ca2+-binding affinity of 3 and 5-fold, respectively. L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y affected Mg2+ and Ca2+-binding to a different degree, increasing Mg2+-binding more than they increased Ca2+-binding (Figure 10).

Mg2+ binding affinities from Thermodynamic Integration (TI)

The binding affinity for each protein structure determined by Thermodynamic Integration was averaged over 5 independent runs and was , , , , respectively. The TI calculated Mg2+ binding affinities were in good agreement with the ITC data, except for L48Q N-cTnC. The ITC data showed a much stronger increase in Mg2+ sensitivity for the L48Q N-cTnC. However, all mutated structures were shown to have increased Mg2+ sensitivity compared to WT cTnC. The values were similar for TI and ITC (1.066 and 1.63 , respectively). The values also showed good agreement for TI and ITC (1.225 and 1.79 , respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2 -.

Mg2+ thermodynamic integration free energy of WT and mutant N-cTnC structures

| N-cTnC Structure | ΔGTI(kcal/mol) ± std. dev. | ΔΔGTI |

|---|---|---|

| WT | −5.139 ± 2.308 | |

| L48Q | −5.481 ± 0.719 | −0.342 |

| Q50R | −6.205 ± 2.112 | −1.066 |

| C84Y | −6.364 ± 1.372 | −1.225 |

Statistically significant differences not found

Discussion

The binding of Ca2+ to site II within the N-terminal domain of cTnC is the fundamental molecular precursor to a series of conformational changes that culminate in cross bridge formation and force production. As such, changes in the sequence of this highly conserved protein often has grave consequences for the force production capabilities of the heart [75] and likely leads to cardiac remodeling. The six variants examined in this study all occur outside the EF hand binding regions and must allosterically alter Ca2+ affinity. Given the location of each mutation of interest and the desire to focus on changes in the binding interaction, we exclusively studied the N-terminal domain of cTnC. The mutations in question have also been studied at various levels of complexity by numerous groups, whose findings are in general agreement with our own [3, 55, 59, 61–63, 65]. In this study we found that the Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding affinity of the five HCM and single DCM variants were variable and different from the WT. The Mg2+ affinities measured here, with the WT serving as a point of comparison are physiologically significant and indicate a potential modulatory role for this cation in EC coupling.

The recently published Cryo-EM structure of the cardiac thin filament has shown that cardiomyopathy associated variants in troponin overwhelmingly occur in regions that interface with the actin-tropomyosin complex [76]. Variants which occur at a distance from these interfaces, are still most likely to affect changes through altered interactions with other proteins of the contractile complex [77]. These interactions may be affected by mutations occurring at the interface between proteins within the complex [78]. Thin filament loss-of-function variants are associated with HCM as they increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction by decreasing the steric hinderance of myosin binding sites. In contrast, gain-of-function mutations in N-cTnC have a sensitizing effect given that in the holo-state, this domain displaces the TnISW from actin, moves tropomyosin, and unhinders myosin binding sites [21].

ITC directly measures the binding interaction and subsequent conformational change as an alternative to the introduction of naturally occurring fluorophores such as F27W [79i] or synthetic fluorophores such as IAANS [41, 80]. These reporters can be used to quantify the structural changes that proceed the binding interaction and thus, indirectly measure affinity. Fluorescence can also be used to report on the dissociation of Ca2+ from cTnC, the cTn complex, or the TF by utilizing chelators such as EDTA and rapid fluid changes through stopped flow experiments [53]. ITC has the sensitivity to detect minute enthalpic fluctuations which accompany these interactions, accurately detecting changes to within 0.1 μcal [81]. That is, not withstanding the inherent limitations associated with every experimental technique. For this assay a limitation results from the absence of other components of the cTn complex, particularly cTnI which plays a central role to the regulation of TF Ca2+ handling [41, 76, 82–84]; thus care must be taken when translating these findings to more complex systems.

The binding of Ca2+ to N-terminal cTnC is driven through a balance between the conformational strain resulting from the interaction and the energetics of exposing a hydrophobic cleft to the aqueous environment [85]. We posit that the changes in affinity seen in each TNNC1 variant result from either the destabilization of the apo-state protein or the stabilization of the solvent exposed state [55]. We found that all of the HCM associated cTnC variants studied had a more negative ΔG compared to the WT, consistent with our previously published MD Simulations [55]. Work by Bowman and Lindert corroborates these findings and suggests a unifying theory that increased frequency of opening may result from the lowered energetic cost of exposing the N-terminal domain of cTnC. The placement of more hydrophilic amino acids that destabilize hydrophobic packing in the closed state and stabilize the open, solvent-exposed state that follows, may allow for this mechanism of action [86].

A8V was only moderately different from the WT, consistent with previous findings that suggest this mutation alters the interaction of cTnC with other TF proteins rather than altering the Ca2+ binding affinity directly [63, 82]. The locus of valine near the interface with N-cTnI and strengthens interaction with the switch peptide making this a distinct possibility [55, 87]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) data suggest a slight increase in the opening frequency in the apo-state relative to the WT [59]. In our study, the binding affinity of this mutant for both Ca2+ and Mg2+ was higher than the WT. In pre-incubation experiments in which both cations were present, the A8V construct had lower than WT affinity for Ca2+ (Figures 2, 3, and 6).

Figure 6:

Representative isotherms for each titration condition into A8V, L29Q, and A31S N-cTnC. The 3 most N-terminal mutations are shown; A8V, L29Q, and A31S from top to bottom. On the left panel, titration of Ca2+ into apo-state protein is shown with the next panels show the titration of Ca2+ into 1 mM and 3 mM Mg2+ pre-incubated N-cTnC. The right most panel shows the titration of Mg2+ into apo-state N-cTnC. The majority of titrations are characterized by an endothermic interaction with the exception of A31S, where pre-incubation with Mg2+ resulted in an exothermic interaction with Ca2+.

L29Q nearly doubled the KA for Ca2+ compared to WT, though the difference was not statistically significant. It also had greater than WT Mg2+ binding affinity but similar thermodynamic parameters and isotherm characteristics. Fluorescence (F27W) studies on isolated cTnC harboring the L29Q mutation exhibited an nearly 2-fold increase in Ca2+ affinity [41]. A complex system containing the entire contractile apparatus with L29Q cTnC had similar to WT Ca2+ sensitivity [88]. This mutation also changes sensitivity of force generation in a length- and phosphorylation-dependent manner [52]. Changing a hydrophobic residue to one that is polar, sensitizes site II Ca2+ sensitivity [89, 90]. Mechanistically, solvent exposure of an uncharged glutamine may facilitate a greater extent of opening than a hydrophobic leucine [55]. However, our previous work suggests that this variant has the highest closed probability among the seven constructs studied and lowers opening frequency [55]. In contrast, it has been shown through NMR that this mutation may cause a more open N-domain in the cTnC in both the apo- and holo-states [91]. L29Q may open in the holo-state with similar frequency as the WT and have similar energetic requirements as the WT for opening in both the apo- and holo-states [86]. Therefore, it is likely that the effects of this mutation in isolated N-cTnC are minimal and that changes are enacted through modification of the interaction with other cTn complex proteins [41].

The A31S TNNC1 variant is the result of a change of a hydrophobic amino acid for an uncharged one within the site 1 EF hand. In skeletal tissue, there is a great deal of cooperativity between binding to the two N-terminal sites of TnC [92, 93]. This mutant was found to have a greater KA for both Ca2+ and Mg2+ compared to the WT and significantly higher affinity for Ca2+ in both pre-incubation conditions. A31S was found through MD simulations to sample a greater number of interhelical angles and to have a lower average angle between helices A and B [55]. Interestingly, pre-incubation with Mg2+ completely changed the reaction dynamics (Figure 6). ΔH reflects the strength of hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatic forces between the titrant and the target ligand. Optimal placement of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors balances de-solvation of polar groups to contribute to the enthalpy change [94]. The significant change in enthalpy suggests alteration of the number of bonds formed by the side chains of binding site residues or those exposed to the environment following the conformational change. This mutation may stabilize binding site I between helices A and B through formation of an additional hydrogen bond causing local changes that minimally alter global structure [62].

L48Q significantly altered affinity and thermodynamics of the binding interactions studied. The combination of high Ca2+ and Mg2+ affinity resulted in the highest observed KA in both competition conditions. This is not unexpected, as the mutant is located within the BC helical bundle and was strategically engineered to increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of force production [3]. Our previously published MD simulations suggest that the absence of a hydrophobic residue disrupts hydrophobic packing in the AB domain. We also reported that the L48Q mutant opens more frequently than the other constructs [55, 86]. The changes in ΔH are likely due in part to the presence of an additional hydrogen bonds resulting from the introduction of a polar amino acid in a key domain of cTnC. In vivo, this would increase the opportunities for interaction with the TnIsw [17, 95, 96]. Tikunova et al. originally suggested that despite a shift towards the Ca2+-bound state, resulting from a reduction in hydrophobic contact between helices NAD and BC, the solvent exposure of the N-domain is minimized by numerous side chain contacts. Their hypothesis regarding the disruption of hydrophobic interactions and minimization of exposure to the surrounding solvent is reconcilable with our findings and explains the much lower ΔS associated with this set of titrations [3].

Q50R is a relatively recently identified mutation that has yet to be fully explored. This mutant replaces a polar side chain with one that is bulky and charged. Given the results in L48Q and the vicinity of these residues, it is conceivable that the packing of helices NAD and BC is also disrupted by this mutant. This mutant had a much higher affinity than WT for both Ca2+ and Mg2+. Similar to L48Q, the interaction with Ca2+ was exothermic in the pre-incubation condition. Our previous work suggests that Q50R is more frequently open than the WT cTnC [55]. The reduced entropic cost of exposing a more charged residue to the aqueous environment may explain the decreased ΔS of the system, yet the adjacent residues would also be exposed to variable degrees in this mutant. Further, the energetic cost of opening the hydrophobic patch is increased in this mutant in comparison to the WT protein that has a less stable closed conformation [86].

C84Y places a bulky hydrophobic side chain in the region immediately preceding the flexible DE linker that is bound and stabilized in the open state by the TnISW. This bulky tyrosine may act as a wedge to reduce interaction with the TnISW and thus increase the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development in skinned fibers [63, 82]. C84Y was thermodynamically similar across all titrations with Q50R; given the location of these mutants, this does not necessarily suggest a similar mode of action. Interestingly however, our MD Simulations previously showed that a hydrophobic interaction between C84 and Q50 may be disrupted by this tyrosine. The bulky tyrosine in helix D may reduce the entropic cost of opening associated with the binding interaction, this is consistent with the observed, lower than WT ΔS values in C84Y N-cTnC [55].

The calculated Mg2+ binding affinity results using TI were in good agreement with the ITC values. We observed increased ion sensitization for all mutant N-cTnC structures. In particular the values for Q50R and C84Y mutations aligned very well with the experimental data. The absolute binding affinities calculated for WT, Q50R and C84Y were overestimated compared to the ITC values by less than 1 kcal/mol. Parameterization of cations, especially Mg2+, in simulating biological systems has proven to be difficult [97, 98]. This could offer a potential explanation for the overestimation and relatively high standard deviations observed in the averaged absolute binding affinities. Another source of discrepancy between the in silico and ITC results, arises from the fact that there is no PDB structure of Mg2+ bound to site II of N-cTnC. In order to create the starting structure for TI simulations the PDB 1AP4 served as the base model, and Mg2+ was substituted in place of the Ca2+ ion. If crystal structures of Mg2+-bound WT N-cTnC and mutants were to exist, the use of these structures could potentially improve the IT results. TI of the L48Q mutant did not produce nearly as strong an increased Mg2+ sensitization as observed in the ITC data. We speculate that this could possibly be attributed to large conformational changes that were unable to be captured using TI. The timescale of the TI simulations was only 5 ns, which was insufficient to properly sample any large protein conformational changes.

Our data clearly demonstrate that each of the N-cTnC variants, including the WT, responded significantly but variably to the presence of Mg2+. Except for A31S, each mutant site II has a significantly lower Ca2+ binding affinity in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+. The degree of desensitization is best described as A8V>L29Q>Q50R>C84Y>L48Q. Given these observations, it is possible that Mg2+ binding dampens the presupposed sensitizing effect of HCM-associated mutations (Chang and Potter 2005); at the very least, the role of background Mg2+ in modifying Ca2+ sensitivity of force production cannot be ignored.

Given the high concentration of free Mg2+ in the cytosol and its similarities as a divalent cation and the small difference in atomic radius in comparison to Ca2+, this ion is a candidate for binding to site II of cTnC. A polar serine at residue 69 and a negatively charged glutamic acid at residue 76 in the EF hand binding site II of N-cTnC, create a domain that is amicable to Mg2+ binding [99, 100]. Despite previous work in this field, the central dogma in the literature is largely dismissive of the possibility that physiologically relevant concentrations of Mg2+ bind to site II. We previously explored Mg2+ binding to site II in full length and N-terminal cTnC and established competition with Ca2+ at physiological concentrations of each cation in the cell [51]. In this work, we explore the hypothesis that Ca2+ and Mg2+ compete, where affinity for each cation is allosterically modified by single amino acid changes outside the binding domain.

Tikunova and Davis have shown that Mg2+, unlike Ca2+, does not cause a structural change in the troponin complex upon binding but does significantly alter the affinity of cTnC for Ca2+ with 3 mM Mg2+ causing a more than 3-fold reduction in Ca2+ binding affinity. Moreover, Mg2+ reverses the fluorescence change of Ca2+ saturated cTnC; that is to say, their data supports the concept that 3 mM Mg2+ competes for binding to site II [3].

The molecular mechanisms which underpin the role of cellular Mg2+ in cardiac contractility are yet to be fully understood and require further exploration. We measured a 47-fold difference in the affinity of WT N-cTnC for Ca2+ (64.48 ± 3.09 ×103 M−1) in comparison to Mg2+ (1.43 ± 0.07 ×103 M−1). However, the free Mg2+ concentration is 3 orders of magnitude more abundant in the cytosol at systole than Ca2+ (1 μM vs. 1000 μM) [101, 102] and may compete for binding to site II in addition to the structural sites III and IV [51]. Mg2+ deficiency has been linked to cardiac disease including arrhythmias, hypertension, and congestive heart failure [103–106]. It is possible that Mg2+ modulates the role of Ca2+ and alters activation of contractile pathways that are governed by this messenger.

Less than 15 mins of ischemia can substantially decrease [ATP]i resulting in a three-fold increase in free [Mg2+] [107]. This elevated Mg2+ may compete with Ca2+ for binding to cytosolic buffers such as cTnC. Overall, our study suggests that the effect of cellular Mg2+ on the Ca2+ binding properties of site II within N-cTnC is not negligible. This effect may be even more pronounced in HCM- and DCM-mutant N-cTnC, where both cytosolic concentrations of free Mg2+ (1 mM) and elevated Mg2+ that may accompany energy depleted states (3 mM) causing a more significant reduction in affinity compared to the WT through alterations in structural dynamics and the energetic landscape of each interaction.

Conclusions

The interaction of Ca2+ with mutant N-cTnCs occurred with higher than WT affinities, with the highest affinity seen in the L48Q mutant. In general, A31S, L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y had the highest affinities for both Ca2+ and Mg2+. Thermodynamic, structural, and simulation work by our group and others suggests a common mechanism whereby mutants destabilize hydrophobic interactions between helices NAD and BC elevate binding affinity.

We found that the affinity for Mg2+ (~1.5 × 103 M−1) was at least an order of magnitude lower than that seen for Ca2+ (~60 × 103 M−1). The change in affinity observed when comparing the Mg2+ pre-incubated N-cTnC and apo-state protein was variable in each mutant and significantly different from the WT. Moreover, 1 mM and 3 mM Mg2+ caused a graded decrease in the amount of binding and affinity for Ca2+. In contrast to Ca2+, cellular Mg2+ does not cause a conformational change upon binding to site II of cTnC and thus cannot initiate contraction. However, Mg2+ has been shown, both here and in numerous previous studies to interact with the same N-terminal locus. Cellular Mg2+ may be altered in disease states; for example, it may be elevated in ischemic stress or decreased as in hyperparathyroidism. Moreover, Mg2+-binding to cTnC may alter the already skewed Ca2+-cTnC binding interaction which exists in diseases such as HCM or DCM, further affecting significant changes in cardiomyocyte EC coupling.

Materials and Methods

Construct Preparations

Recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as described previously [66]. In brief, the human cTnC gene (TNNC1) within the pET-21a(+) vector was ordered from Novagen and the Phusion site directed mutagenesis kit (Thermo) was used to introduce a stop codon at residue 90, followed by single base pair changes to introduce all 6 variants of interest (A8V, L29Q, A31S, L48Q, Q50R, and C84Y) on separate N-terminal constructs (cTnC1-89). Mutagenesis was carried out with preliminary steps using the DH5α E. coli strain to house the plasmids. Following the mutagenesis and confirmation by sequencing, the constructs were transformed into the BL21(DE3) expression strain and stored as glycerol stocks.

Protein Expression

100 mL of Lysogeny Broth (LB) supplemented with 50 μg/mL of Ampicillin and a stab of the glycerol stock was grown overnight at 37⁰ C for 16 – 20 hrs with shaking at 225-250 rpm. 1 L flasks of LB were induced with 1-5% of the overnight culture and supplemented with the same concentration of antibiotic and grown under the same conditions for ~3 hrs (until the OD600 was between 0.8-1.0). The culture was then supplemented with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and grown for a further 3 – 4 hrs. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in the Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl and 100 mM NaCl at pH 8.0). The suspended pellet was stored at −80° C until purification.

Protein Purification

The pellet was thawed and sonicated at ~80% amplitude in 30 second intervals for a total time of 3 – 4 mins with each intermittent period spent on ice. The cells were then spun 2 times, for 15 minutes each at 30,000 ×g and the supernatant kept, and the pellet discarded. The supernatant was filtered as needed and applied to a 15 mL fast-flow DEAE or Q Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), pre-equilibrated with Buffer A (in mM 50 tris-Cl, 100 NaCl, and 1 dithiothreitol (DTT) at pH 8.0). Buffer B (Buffer A + 0.55 M NaCl) was applied over a 180 mL protocol, in which the concentration was ramped up from 0 to 100% to elute the proteins of interest. Fractions containing the N-terminal cTnC construct were identified by SDS PAGE and pooled. An Amicon centrifugal concentrator (Millipore) with a 3 KDa cut-off was used to concentrate the pooled samples to a volume of 3 – 5 mL. The pooled samples were then applied to a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-100 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with Buffer A. The fractions were again analyzed by SDS PAGE and those containing the protein of interest, free of contaminants were pooled, concentrated, and stored at −80° C.

ITC Protocol

The protein was dialyzed against 3 exchanges of 2 L for at least 6 hrs each with ITC Buffer 1 containing (in mM) 50 HEPES, 150 KCl, 2 EDTA, and 15 β-mercaptoethanol (BME) at pH 7.2. ITC Buffer 2 was identical to the first but did not contain EDTA; this was the second buffer used for equilibration and was used after the first to remove the EDTA contained in Buffer 1. ITC Buffer 3 was identical to the second but contained significantly reduced BME (2 mM). Buffer 3 was used to dilute the protein and Ca2+/Mg2+ prior to ITC experiments. A Nanodrop instrument was used to gain a preliminary measure of the protein concentration using an extinction coefficient of 1490 M−1*cm−1 and a molecular weight of 10.4 kDa. An initial ITC run was used to determine the molar ratio (N). Given that the concentration of the titrant is known and the number of cation binding sites in N-cTnC is 1, the concentration of folded, functional protein was determined and adjusted in subsequent runs to give an N of 1.0.

The protein was diluted in the final dialysis buffer to a final concentration of 100 μM. The titrating solutions were prepared from 1.00 M Ca2+ and Mg2+ stocks (Sigma) by serial dilution in the final dialysis buffer. For the apo-state experiments, 2 mM Ca2+ and 20 mM Mg2+ were titrated into 100 μM N-cTnC with the exception of the L48Q in which 2 mM Mg2+ was used. For competition experiments, the Apo-state construct was pre-incubated with Mg2+ to a final concentration of 1 mM or 3 mM Mg2+ prior to titration with 2 mM Ca2+. Titrant into buffer blank experiments were carried out to gauge the impact of these experiments and indicate minimal heat change resulting from the interactions (Figure S1). For all experiments, 19 titrations, 60 seconds apart were performed with the first being 0.8 μL and each subsequent injection 2 μL. The cell contents were mixed at 750 rpm throughout the titration. All titrations were carried out at 25° C.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data were imported and analyzed in Origin 8.0 software for Microcal ITC200 (Northampton, MA). After saturation, the final 2-3 data points were averaged, the heat was subtracted from all injections as a control for heat of dilution and non-specific interactions. Least-squares regression was used to fit each titration after the first (dummy) injection was removed with minimization of chi-square and visual evaluation used to determine the goodness-of-fit for a single binding site model. Following establishment of the protein concentration based on the obtained N value for each apo-state Ca2+ titration for each construct, the same dilution of protein was used for each other titration and the N-value fixed to 1.00 to facilitate data fitting. The various thermodynamic parameters were averaged and reported as a mean ± SEM. The difference between the means was compared using a one-way ANOVA. This was followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test to determine where significant (p<0.05) differences existed (Figure 2).

Thermodynamic Integration (TI)

The structure of the N-terminal domain of cardiac troponin C (N-cTnC) was obtained from PDB:1AP4 [67], this structure contained N-cTnC with a single Ca2+ ion bound. Since there was no model of Mg2+ bound N-cTnC in the protein databank, we made use of the Mg2+ substituted structure as outlined in our previous work [51]. The model was then solvated using the tLeap module of AMBER 16 [68] in a 12 TIP3P water box and neutralized with Na+ ions; the forcefield used to describe the protein was ff14SB [69]. In order to complete the thermodynamic cycle, a system containing the Mg2+ ion was prepared using the tLeap module, referencing the optimized Mg2+ parameters from Li et. al. [70], and solvated in a 12 TIP3P water box. Simulations were conducted under NPT conditions using the Berendsen barostat and periodic boundary conditions. The system was minimized for 2000 cycles and heated to 300 K using the Langevin thermostat over 500 ps prior to the 5 ns production with a time step of 2 fs. The SHAKE algorithm was employed to constrain all bonds involving hydrogen atoms, and the Particle Mesh Ewald method [71] was utilized to calculate electrostatic interactions of long distances with a cutoff of 10.

The alchemical thermodynamic cycle used for ligand binding has been detailed previously by Leelananda and Lindert [72]. In this implementation of TI, the method consisted of three steps for ligand (Mg2+) in protein: 1) introduction of harmonic distance restraints; 2) removal of electrostatic interactions, and 3) removal of van der Waals forces. TI consisted of two steps for the ligand in water system: removal of electrostatic interactions and removal of van der Waals forces. The coupling parameter increased incrementally by 0.1 from 0.0 – 1.0 for each transitional step of the thermodynamic cycle. During each simulation dV/d values were collected every 2 ps resulting in 5000 data points per transitional step of for further analysis. The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) [73] was used to calculate the relative free energies of the simulations across all values of . Free energy corrections were made due to the introduction of the distance restraints and to correct for the charge of the system as described previously [51]. For each system, 5 independent runs were performed, and the results averaged. The specific distance restraints for all protein structures are shown in Table 1.

The cTnC variants (L48Q, Q50R, C84Y) were constructed using the protein mutagenesis tool in PyMOL[74][69] and the Mg2+ substituted representative model of N-cTnC serving as the base model. TI simulations were performed on the mutant structure as detailed above for the wild type.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4:

Representative isotherms are presented to quantify the heat signal from the interaction with each of Ca2+ and Mg2+ with the buffer. N-values do not present any utility and are included for completeness. The buffer titrations involve only transient binding interactions such as hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals forces if indeed they are quantifiable, between the solutes and solvents; this system contains no protein and no true binding sites. The scale may be used as measure of the heat change in the system and a proxy to compare with the titrant into N-cTnC conditions. The values measured when a single binding site model was used to fit each titration are presented in the table.

Figure 5:

Representative isotherms for each titration condition in the WT N-cTnC construct. From the right, the titration of Ca2+ into apo-state N-cTnC is shown, the next two panels show the titration of Ca2+ into 1 mM and 3 mM Mg2+ incubated WT N-cTnC. The right-most panel shows titration of Mg2+ into apo-state protein. Each titration is similarly endothermic with the scales indicating differences in absolute value of change in enthalpy.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research which funded this research project.

Abbreviations:

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- cTnC

Cardiac troponin C

- cTn

Cardiac troponin

- TNNC1

cTnC gene

- TnIsw

cTnI switch peptide

- DCM

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- EC

Excitation-contraction

- HCM

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

- IPTG

Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- ITC

Isothermal titration calorimetry

- LB

Lysogeny Broth

- N

Molar ratio

- MD

Molecular Dynamics

- MBAR

Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio

- N-cTnC

N-terminal domain of cardiac troponin C

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- TI

Thermodynamic Integration

- TF

Thin filament

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Potter JD & Gergely J (1975) The calcium and magnesium binding sites on troponin and their role in the regulation of myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 250, 4628–4633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturtevant JM (1977) Heat capacity and entropy changes in processes involving proteins, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74, 2236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tikunova SB & Davis JP (2004) Designing calcium-sensitizing mutations in the regulatory domain of cardiac troponin C, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279, 35341–35352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM (2000) Calcium Fluxes Involved in Control of Cardiac Myocyte Contraction, Circulation Research. 87, 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sia SK, Li MX, Spyracopoulos L, Gagné SM, Liu W, Putkey JA & Sykes BD (1997) Structure of cardiac muscle troponin C unexpectedly reveals a closed regulatory domain, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272, 18216–18221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirschenlohr HL, Grace AA, Vandenberg JI, Metcalfe JC & Smith GA (2000) Estimation of systolic and diastolic free intracellular Ca2+ by titration of Ca2+ buffering in the ferret heart, The Biochemical journal. 346 Pt 2, 385–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tardiff JC (2011) Thin filament mutations: developing an integrative approach to a complex disorder, Circulation research. 108, 765–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT & Bild DE (1995) Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study, Circulation. 92, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS & Maron BJ (2015) New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 65, 1249–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seidman CE & Seidman JG (2011) Identifying sarcomere gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a personal history, Circ Res. 108, 743–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashrafian H & Watkins H (2007) Reviews of translational medicine and genomics in cardiovascular disease: new disease taxonomy and therapeutic implications: Cardiomyopathies: Therapeutics based on molecular phenotype, Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 49, 1251–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada K & Morimoto S (2004) Inherited cardiomyopathies as a troponin disease, The Japanese journal of physiology. 54, 307–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinoso TR, Landim-Vieira M, Shi Y, Johnston JR, Chase PB, Parvatiyar MS, Landstrom AP, Pinto JR & Tadros HJ (2021) A comprehensive guide to genetic variants and post-translational modifications of cardiac troponin C, Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 42, 323–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott P & McKenna WJ (2004) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Lancet (London, England). 363, 1881–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldspink PH, Warren CM, Kitajewski J, Wolska BM & Solaro RJ (2021) A perspective on personalized therapies in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 77, 317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC & Mueller FO (1996) Sudden death in young competitive athletes: clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles, JAMA. 276, 199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis J, Davis LC, Correll RN, Makarewich CA, Schwanekamp JA, Moussavi-Harami F, Wang D, York AJ, Wu H & Houser SR (2016) A tension-based model distinguishes hypertrophic versus dilated cardiomyopathy, Cell. 165, 1147–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuo T, Kono F & Fujiwara S (2019) Effects of the cardiomyopathy-causing E244D mutation of troponin T on the structures of cardiac thin filaments studied by small-angle X-ray scattering, Journal of structural biology. 205, 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katrukha I (2013) Human cardiac troponin complex. Structure and functions, Biochemistry (Moscow). 78, 1447–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalyva A, Parthenakis FI, Marketou ME, Kontaraki JE & Vardas PE (2014) Biochemical characterisation of Troponin C mutations causing hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies, Journal of muscle research and cell motility. 35, 161–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobacman LS & Cammarato A (2021) Cardiomyopathic troponin mutations predominantly occur at its interface with actin and tropomyosin, Journal of General Physiology. 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfares AA & Kelly MA (2015) Results of clinical genetic testing of 2,912 probands with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: expanded panels offer limited additional sensitivity. 17, 880–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tadros HJ, Life CS, Garcia G, Pirozzi E, Jones EG, Datta S, Parvatiyar MS, Chase PB, Allen HD & Kim JJ (2020) Meta-analysis of cardiomyopathy-associated variants in troponin genes identifies loci and intragenic hot spots that are associated with worse clinical outcomes, Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 142, 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willott RH, Gomes AV, Chang AN, Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR & Potter JD (2010) Mutations in Troponin that cause HCM, DCM AND RCM: what can we learn about thin filament function?, Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 48, 882–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai LJ, Friedman PA & Quamme GA (1997) Phosphate depletion diminishes Mg2+ uptake in mouse distal convoluted tubule cells, Kidney international. 51, 1710–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romani A & Scarpa A (1992) Regulation of cell magnesium, Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 298, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maguire ME (2006) Magnesium transporters: properties, regulation and structure, Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 11, 3149–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause SM & Rozanski D (1991) Effects of an increase in intracellular free [Mg2+] after myocardial stunning on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport, Circulation. 84, 1378–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkels J, Van Echteld C & Ruigrok T (1989) Intracellular magnesium during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: possible consequences for postischemic recovery, Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 21, 1209–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter JD, Robertson SP & Johnson JD (1981) Magnesium and the regulation of muscle contraction, Federation proceedings. 40, 2653–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogawa Y (1985) Calcium binding to troponin C and troponin: effects of Mg2+, ionic strength and pH, The Journal of Biochemistry. 97, 1011–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zot AS & Potter JD (1987) Structural aspects of troponin-tropomyosin regulation of skeletal muscle contraction, Annual review of biophysics and biophysical chemistry. 16, 535–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morimoto S (1991) Effect of myosin cross-bridge interaction with actin on the Ca2+-binding properties of troponin C in fast skeletal myofibrils, The Journal of Biochemistry. 109, 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francois JM, Gerday C, Prendergast FG & Potter JD (1993) Determination of the Ca2+ and Mg2+ affinity constants of troponin C from eel skeletal muscle and positioning of the single tryptophan in the primary structure, J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 14, 585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.She M, Dong WJ, Umeda PK & Cheung HC (1998) Tryptophan mutants of troponin C from skeletal muscle: an optical probe of the regulatory domain, European journal of biochemistry. 252, 600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen TS, Yates LD & Gordon AM (1992) Ca2+-dependence of structural changes in troponin-C in demembranated fibers of rabbit psoas muscle, Biophysical journal. 61, 399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godt RE & Morgan JL (1984) Contractile responses to MgATP and pH in a thick filament regulated muscle: studies with skinned scallop fibers, Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 170, 569–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godt RE (1974) Calcium-activated tension of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Dependence on magnesium adenosine triphosphate concentration, The Journal of general physiology. 63, 722–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Best PM, Donaldson SK & Kerrick WG (1977) Tension in mechanically disrupted mammalian cardiac cells: effects of magnesium adenosine triphosphate, The Journal of physiology. 265, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis JP, Rall JA, Reiser PJ, Smillie LB & Tikunova SB (2002) Engineering competitive magnesium binding into the first EF-hand of skeletal troponin C, The Journal of biological chemistry. 277, 49716–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li AY, Stevens CM, Liang B, Rayani K, Little S, Davis J & Tibbits GF (2013) Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy related cardiac troponin C L29Q mutation alters length-dependent activation and functional effects of phosphomimetic troponin I*. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Holroyde M, Robertson S, Johnson J, Solaro R & Potter J (1980) The calcium and magnesium binding sites on cardiac troponin and their role in the regulation of myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255, 11688–11693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebashi S & Ogawa Y (1988) Ca2+ in contractile processes, Biophysical chemistry. 29, 137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fabiato A & Fabiato F (1975) Effects of magnesium on contractile activation of skinned cardiac cells, The Journal of physiology. 249, 497–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Donaldson SK & Kerrick WG (1975) Characterization of the effects of Mg2+ on Ca2+- and Sr2+-activated tension generation of skinned skeletal muscle fibers, The Journal of general physiology. 66, 427–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerrick WG, Zot HG, Hoar PE & Potter JD (1985) Evidence that the Sr2+ activation properties of cardiac troponin C are altered when substituted into skinned skeletal muscle fibers, The Journal of biological chemistry. 260, 15687–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solaro RJ & Shiner JS (1976) Modulation of Ca2+ control of dog and rabbit cardiac myofibrils by Mg2+. Comparison with rabbit skeletal myofibrils, Circ Res. 39, 8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashley CC & Moisescu DG (1977) Effect of changing the composition of the bathing solutions upon the isometric tension-pCa relationship in bundles of crustacean myofibrils, The Journal of physiology. 270, 627–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donaldson SK, Best PM & Kerrick GL (1978) Characterization of the effects of Mg2+ on Ca2+- and Sr2+-activated tension generation of skinned rat cardiac fibers, The Journal of general physiology. 71, 645–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka H, Takahashi H & Ojima T (2013) Ca2+-binding properties and regulatory roles of lobster troponin C sites II and IV, FEBS letters. 587, 2612–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rayani K, Seffernick J, Li AY, Davis JP, Spuches AM, Van Petegem F, Solaro RJ, Lindert S & Tibbits GF (2021) Binding of calcium and magnesium to human cardiac Troponin C, The Journal of biological chemistry, 100350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang B, Chung F, Qu Y, Pavlov D, Gillis TE, Tikunova SB, Davis JP & Tibbits GF (2008) Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related cardiac troponin C mutation L29Q affects Ca2+ binding and myofilament contractility, Physiological genomics. 33, 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tikunova SB, Liu B, Swindle N, Little SC, Gomes AV, Swartz DR & Davis JP (2010) Effect of calcium-sensitizing mutations on calcium binding and exchange with troponin C in increasingly complex biochemical systems, Biochemistry. 49, 1975–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomes AV & Potter JD (2004) Molecular and cellular aspects of troponin cardiomyopathies, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1015, 214–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevens CM, Rayani K, Singh G, Lotfalisalmasi B, Tieleman DP & Tibbits GF (2017) Changes in the dynamics of the cardiac troponin C molecule explain the effects of Ca2+-sensitizing mutations, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 292, 11915–11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohki S, Ikura M & Zhang M (1997) Identification of Mg2+-binding sites and the role of Mg2+ on target recognition by calmodulin, Biochemistry. 36, 4309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Malmendal A, Evenas J, Thulin E, Gippert GP, Drakenberg T & Forsen S (1998) When size is important. Accommodation of magnesium in a calcium binding regulatory domain, The Journal of biological chemistry. 273, 28994–9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andersson M, Malmendal A, Linse S, Ivarsson I, Forsen S & Svensson LA (1997) Structural basis for the negative allostery between Ca(2+)- and Mg(2+)-binding in the intracellular Ca(2+)-receptor calbindin D9k, Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 6, 1139–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cordina NM, Liew CK, Gell DA, Fajer PG, Mackay JP & Brown LJ (2013) Effects of Calcium Binding and the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy A8V Mutation on the Dynamic Equilibrium between Closed and Open Conformations of the Regulatory N-Domain of Isolated Cardiac Troponin C, Biochemistry. 52, 1950–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marques MA, Landim-Vieira M, Moraes AH, Sun B, Johnston JR, Jones KMD, Cino EA, Parvatiyar MS, Valera IC & Silva JL (2021) Anomalous structural dynamics of minimally frustrated residues in cardiac troponin C triggers hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Chemical science. 12, 7308–7323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoffmann B, Schmidt-Traub H, Perrot A, Osterziel KJ & Gessner R (2001) First mutation in cardiac troponin C, L29Q, in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Human mutation. 17, 524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Parvatiyar MS, Landstrom AP, Figueiredo-Freitas C, Potter JD, Ackerman MJ & Pinto JR (2012) A mutation in TNNC1-encoded cardiac troponin C, TNNC1-A31S, predisposes to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and ventricular fibrillation, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287, 31845–31855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landstrom AP, Parvatiyar MS, Pinto JR, Marquardt ML, Bos JM, Tester DJ, Ommen SR, Potter JD & Ackerman MJ (2008) Molecular and functional characterization of novel hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility mutations in TNNC1-encoded troponin C, Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 45, 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gonzalez-Martinez D, Johnston JR, Landim-Vieira M, Ma W, Antipova O, Awan O, Irving TC, Chase PB & Pinto JR (2018) Structural and functional impact of troponin C-mediated Ca2+ sensitization on myofilament lattice spacing and cross-bridge mechanics in mouse cardiac muscle, Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 123, 26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, van Tintelen JP, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Werf R, Jongbloed JD, Paulus WJ, Dooijes D & van den Berg MP (2010) Peripartum cardiomyopathy as a part of familial dilated cardiomyopathy, Circulation. 121, 2169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stevens CM, Rayani K, Genge CE, Singh G, Liang B, Roller JM, Li C, Li AY, Tieleman DP & van Petegem F (2016) Characterization of Zebrafish Cardiac and Slow Skeletal Troponin C Paralogs by MD Simulation and ITC, Biophysical journal. 111, 38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Spyracopoulos L, Li MX, Sia SK, Gagné SM, Chandra M, Solaro RJ & Sykes BD (1997) Calcium-Induced Structural Transition in the Regulatory Domain of Human Cardiac Troponin C, Biochemistry. 36, 12138–12146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Case DA, Betz RM, Cerutti DS, Cheatham I, T. E, Darden TA, Duke RE, Giese TJ, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Homeyer N, Izadi S, Janowski P, Kaus J, Kovalenko A, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C, Luchko T, Luo R, Madej B, Mermelstein D, Merz KM, Monard G, Nguyen H, Nguyen HT, Omelyan I, Onufriev A, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Simmerling CL, Botello-Smith WM, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xiao L & Kollman PA (2016) AMBER 2016 in University of California, San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE & Simmerling C (2015) ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB, Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 11, 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li P, Roberts BP, Chakravorty DK & Merz KM (2013) Rational Design of Particle Mesh Ewald Compatible Lennard-Jones Parameters for +2 Metal Cations in Explicit Solvent, J Chem Theory Comput. 9, 2733–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H & Pedersen LG (1995) A smooth particle mesh Ewald method, The Journal of Chemical Physics. 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leelananda SP & Lindert S (2016) Computational methods in drug discovery, Beilstein J Org Chem. 12, 2694–2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shirts MR & Chodera JD (2008) Statistically optimal analysis of samples from multiple equilibrium states, J Chem Phys. 129, 124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System in, Schrödinger, LLC, [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gillis TE, Marshall CR & Tibbits GF (2007) Functional and evolutionary relationships of troponin C, Physiol Genomics. 32, 16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamada Y, Namba K & Fujii T (2020) Cardiac muscle thin filament structures reveal calcium regulatory mechanism, Nature communications. 11, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greenberg MJ & Tardiff JC (2021) Complexity in genetic cardiomyopathies and new approaches for mechanism-based precision medicine, Journal of General Physiology. 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baxley T, Johnson D, Pinto JR & Chalovich JM (2017) Troponin C mutations partially stabilize the active state of regulated actin and fully stabilize the active state when paired with Δ14 TnT, Biochemistry. 56, 2928–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gillis TE, Blumenschein TM, Sykes BD & Tibbits GF (2003) Effect of temperature and the F27W mutation on the Ca2+ activated structural transition of trout cardiac troponin C, Biochemistry. 42, 6418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dong W-J, Wang C-K, Gordon AM & Cheung HC (1997) Disparate Fluorescence Properties of 2-[4′-(Iodoacetamido)anilino]-Naphthalene-6-Sulfonic Acid Attached to Cys-84 and Cys-35 of Troponin C in Cardiac Muscle Troponin, Biophysical journal. 72, 850–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Freire E, Mayorga OL & Straume M (1990) Isothermal titration calorimetry, Analytical chemistry. 62, 950A–959A. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pinto JR, Parvatiyar MS, Jones MA, Liang J, Ackerman MJ & Potter JD (2009) A functional and structural study of troponin C mutations related to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, The Journal of biological chemistry. 284, 19090–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramos CH (1999) Mapping subdomains in the C-terminal region of troponin I involved in its binding to troponin C and to thin filament, The Journal of biological chemistry. 274, 18189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Risi CM, Pepper I, Belknap B, Landim-Vieira M, White HD, Dryden K, Pinto JR, Chase PB & Galkin VE (2021) The structure of the native cardiac thin filament at systolic Ca2+ levels, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gifford Jessica L., Walsh Michael P. & Vogel Hans J. (2007) Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix–loop–helix EF-hand motifs, Biochemical Journal. 405, 199–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bowman JD & Lindert S (2018) Molecular Dynamics and Umbrella Sampling Simulations Elucidate Differences in Troponin C Isoform and Mutant Hydrophobic Patch Exposure. 122, 7874–7883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zot HG, Hasbun JE, Michell CA, Landim-Vieira M & Pinto JR (2016) Enhanced troponin I binding explains the functional changes produced by the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation A8V of cardiac troponin C, Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 601, 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dweck D, Hus N & Potter JD (2008) Challenging current paradigms related to cardiomyopathies Are changes in the Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments containing cardiac troponin C mutations (G159D and L29Q) good predictors of the phenotypic outcomes?, Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283, 33119–33128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pearlstone JR, Borgford T, Chandra M, Oikawa K, Kay CM, Herzberg O, Moult J, Herklotz A, Reinach FC & Smillie LB (1992) Construction and characterization of a spectral probe mutant of troponin C: application to analyses of mutants with increased calcium affinity, Biochemistry. 31, 6545–6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.da Silva AC, de Araujo AH, Herzberg O, Moult J, Sorenson M & Reinach FC (1993) Troponin-C mutants with increased calcium affinity, Eur J Biochem. 213, 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Potluri PR, Cordina NM, Kachooei E & Brown LJ (2019) Characterization of the L29Q Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Mutation in Cardiac Troponin C by Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. 58, 908–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Johnson JD, Collins JH & Potter JD (1978) Dansylaziridine-labeled troponin C. A fluorescent probe of Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+-specific regulatory sites, The Journal of biological chemistry. 253, 6451–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Veltri T, Landim-Vieira M, Parvatiyar MS, Gonzalez-Martinez D, Dieseldorff Jones KM, Michell CA, Dweck D, Landstrom AP, Chase PB & Pinto JR (2017) Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cardiac troponin C mutations differentially affect slow skeletal and cardiac muscle regulation, Frontiers in physiology. 8, 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ward WH & Holdgate GA (2001) 7 Isothermal Titration Calorimetry in Drug Discovery in Progress in medicinal chemistry pp. 309–376, Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang D, Robertson IM, Li MX, McCully ME, Crane ML, Luo Z, Tu A-Y, Daggett V, Sykes BD & Regnier M (2012) Structural and functional consequences of the cardiac troponin C L48Q Ca2+-sensitizing mutation, Biochemistry. 51, 4473–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shettigar V, Zhang B, Little SC, Salhi HE, Hansen BJ, Li N, Zhang J, Roof SR, Ho HT, Brunello L, Lerch JK, Weisleder N, Fedorov VV, Accornero F, Rafael-Fortney JA, Gyorke S, Janssen PM, Biesiadecki BJ, Ziolo MT & Davis JP (2016) Rationally engineered Troponin C modulates in vivo cardiac function and performance in health and disease, Nat Commun. 7, 10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cummins PL & Gready JE (1994) Thermodynamic integration calculations on the relative free energies of complex ions in aqueous solution: Application to ligands of dihydrofolate reductase, Journal of Computational Chemistry. 15, 704–718. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Panteva MT, Giambaşu GM & York DM (2015) Comparison of structural, thermodynamic, kinetic and mass transport properties of Mg(2+) ion models commonly used in biomolecular simulations, J Comput Chem. 36, 970–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Reid RE & Procyshyn RM (1995) Engineering magnesium selectivity in the helix-loop-helix calcium-binding motif, Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 323, 115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tikunova SB, Black DJ, Johnson JD & Davis JP (2001) Modifying Mg2+ binding and exchange with the N-terminal of calmodulin, Biochemistry. 40, 3348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dai LJ, Friedman PA & Quamme GA (1997) Cellular mechanisms of chlorothiazide and cellular potassium depletion on Mg2+ uptake in mouse distal convoluted tubule cells, Kidney international. 51, 1008–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bers DM (2002) Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling, Nature. 415, 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Touyz RM (2004) Reactive oxygen species, vascular oxidative stress, and redox signaling in hypertension: what is the clinical significance?, Hypertension (Dallas, Tex : 1979). 44, 248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Weglicki W, Quamme G, Tucker K, Haigney M & Resnick L (2005) Potassium, magnesium, and electrolyte imbalance and complications in disease management, Clinical and experimental hypertension (New York, NY : 1993). 27, 95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mazur A, Maier JA, Rock E, Gueux E, Nowacki W & Rayssiguier Y (2007) Magnesium and the inflammatory response: potential physiopathological implications, Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 458, 48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kolte D, Vijayaraghavan K, Khera S, Sica DA & Frishman WH (2014) Role of magnesium in cardiovascular diseases, Cardiology in review. 22, 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murphy E, Steenbergen C, Levy LA, Raju B & London RE (1989) Cytosolic free magnesium levels in ischemic rat heart, The Journal of biological chemistry. 264, 5622–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takeda S, Yamashita A, Maeda K & Maéda Y (2003) Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca(2+)-saturated form, Nature. 424, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.