Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) in patients results in a massive inflammatory reaction, disruption of blood–brain barrier, and oxidative stress in the brain, and these inciting features may culminate in the emergence of post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE). We hypothesize that targeting these pathways with pharmacological agents could be an effective therapeutic strategy to prevent epileptogenesis. To design therapeutic strategies targeting neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, we utilized a fluid percussion injury (FPI) rat model to study the temporal expression of neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress markers from 3 to 24 h following FPI. FPI results in increased mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and prostanoid receptor EP2, marker of oxidative stress (NOX2), astrogliosis (GFAP), and microgliosis (CD11b) in ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus. The analysis of protein levels indicated a significant increase in the expression of COX-2 in ipsilateral hippocampus and cortex post-FPI. We tested FPI rats with an EP2 antagonist TG8–260 which produced a statistically significant reduction in the distribution of seizure duration post-FPI and trends toward a reduction in seizure incidence, seizure frequency, and duration, hinting a proof of concept that EP2 antagonism must be further optimized for therapeutic applications to prevent epileptogenesis.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury (TBI), post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE), fluid percussion injury (FPI), neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, EP2 antagonist

Epilepsy, a neurological condition characterized by chronic spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRS), is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. It is the fourth most common neurological disorder after Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and migraine, affecting over 3 million Americans and 50 million people worldwide. The underlying cause of epilepsy is still unknown in up to 60% of patients, but in the remaining 40%, traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, alcohol use, neurodegenerative diseases, brain tumor, or infections have been identified as the main causes.1 Antiseizure drugs (ASDs) blunt seizures in epilepsy patients, but they do not cure epilepsy or prevent its development following traumatic or other types of brain injuries.2,3 Post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) is defined as chronic spontaneous recurrent seizures occurring more than a week after traumatic brain injury. The incidence of epilepsy in adults after a penetrating TBI is about 50%.4−7 Molecular pathways that culminate into post-traumatic epilepsy are not completely understood, and no disease-modifying therapeutic agent is currently available for the delay or prevention of PTE; therefore, it is a major unmet medical problem. Animal models are great tools for studying TBI pathophysiology and to develop treatments for the prevention of PTE.8 However, several widely used models have shortcomings in terms of consistency and longitudinal emergence of spontaneous recurring seizures (reviewed in detail).8−11 Advances in the optimization of rostral–parasagittal fluid percussion injury (rpFPI) model12 and, recently, the optimized controlled cortical injury (CCI) model11 show that they encapsulate various characteristics of PTE including spontaneous recurring seizures (SRS), neuropathology, and neuropsychiatric comorbidities among others9−12 suggesting that these are reliable models for testing the therapeutic potential of novel antiepileptogenic agents.

Neuroinflammation is evident in resected epileptic brain tissue, and it is recognized as a driver of epileptogenesis.13,14 It is also a key feature in all epileptogenic brain injuries including TBI.15,16 Neuroinflammation involves induction of cytokines and chemokines, COX-2 and EP2, microgliosis, astrogliosis,17−20 and brain infiltration of peripheral immune cells.21 Although early neuroinflammatory immune responses triggered by the induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and massive formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are necessary to counteract the invading pathogens to the brain during and after brain injuries, the sustained inflammatory and ROS signaling is often not resolved in several brain injuries including TBI. Instead, it contributes to secondary damage to neurons and disruption of synaptic connections, which may ultimately lead to epileptogenesis. This suggests that an anti-inflammatory and/or an antioxidant (suppressor of ROS) drug could be beneficial for the prevention and/or treatment of epilepsy.13,14,22−24 Chronic use of COX-2 inhibitors has been shown to produce adverse cardiovascular effects in patients with other diseases.25−27 COX-2 catalyzes the synthesis of five prostanoid ligands, which activate 11 prostanoid receptors.28 Nonetheless, COX-2 inhibitors have been tested in the seizure models of epileptogenesis to find mixed results, likely due to their inhibition of not only proinflammatory receptors (DP1, EP2, and EP3) but also anti-inflammatory (EP4) and other receptors (e.g., IP, FP, and TP) that mediate downstream signaling pathways.29 To avoid adverse events associated with generic COX-2 drugs,27,30 we recently identified the EP2 receptor as an inflammatory target and developed small-molecule antagonists for EP2 to be used as future anti-inflammatory agents.20,29 We hypothesize that targeting neuroinflammatory and oxidative stress cascades pharmacologically will attenuate the emergence of PTE. Toward this goal, we have utilized a highly optimized rostral–parasagittal fluid percussion injury (rpFPI) model of PTE12 and determined the temporal expression of inflammatory and glial markers, including COX-2, EP2, and NADPH oxidase-2 (NOX2) in the hippocampi and neocortices of rats, beginning from 3 to 24 h after FPI. Moreover, we also explored a proof of concept with a novel anti-inflammatory EP2 antagonist to determine whether a beneficial anti-epileptogenic effect occurs in the rpFPI model.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All experiments were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Animal Welfare Assurance #A3464-01). Surgeries were done under anesthesia with every consideration taken to minimize suffering.

Animals

Sprague–Dawley rats from Charles River, Hollister, CA were induced with rpFPI at 32–36 days of age. Two to three animals were housed in each cage before electrode implantation and single-housed thereafter. Pathogen-free facilities with controlled light (14:10 h light–dark cycle), temperature, humidity, and ad libitum access to food and water were used for the experiment.

Surgical Procedures

rpFPI and epidural electrode implantation were performed, as detailed previously.9,31,32 Briefly, the anesthetized animals were kept ventilated, with the body temperature maintained at 37 °C. For rpFPI, a burr hole was drilled at the suggested position, followed by a pressure pulse (8 ms, 3.8 atm) using an rpFPI device (Scientific Instruments, University of Washington) and measured by a transducer (Entran EPN-D33-100P-IX, Measurement Specialties, Hampton, VA). Ten seconds after injury, we resumed mechanical ventilation, which was terminated when spontaneous breathing resumed. The rate of acute mortality was ∼13%. Three weeks after the injury, epidural electrodes were implanted. Briefly, following 0.75 mm diameter craniotomy, stainless steel screw electrodes measuring 1 mm in diameter were implanted. Five epidural electrodes were used for electrocorticography (ECoG), including one reference electrode placed midline in the frontal bone and two electrodes per parietal bone with headset secured with three anchoring screws. Insulated wires were used to connect the electrodes to gold-plated pins in a plastic pedestal (PlasticsOne Inc., Roanoke, VA). Biocompatible silicone was used to cover the exposed parts following craniotomy (Kwik-Cast., WPI, Sarasota, FL). Dental acrylic (Jet, Lang Dental Manufacturing Co., Wheeling, IL) and VetBond (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) adhesive were used to secure the apparatus onto the skulls.

Preparation and Dosing of TG8–260

TG8–260 is a selective EP2 antagonist with Schild KB 13.2 nM,33 and it has been shown to display anti-inflammatory activities in vitro as well as an in vivo status epilepticus rat model.34 TG8–260 was dissolved in PEG400 and then continuously vortexed while brought to 12.5 mg/mL in 60% PEG400 by a slow stepwise addition of ultrapure water. Animals were administered 2 mL/kg of this solution (= 25 mg/kg dose of TG8–260), or of the 60% PEG400 vehicle alone, twice daily for 5 days. The first dose of TG8–260 or the vehicle was administered intraperitoneally 30 min after rpFPI, and the subsequent nine doses were administered by oral gavage at 12 h intervals (11 am and 11 pm). The dosage was selected based on TG8–260 pharmacokinetics and a published study.33,34 Briefly, the TG8–260 plasma half-life was 2.14 h in rats, but the brain penetration was low, with the brain-to-plasma ratio values in the range of 0.02–0.04; however, its total concentration in the brain with a single IP injection of 20 mg/kg in rats achieved 75 ng/mL (146 ng/mL with pilocarpine insult),34 and these concentrations are about 15–30-fold higher than the potency of the molecule (KB = 13.2 nM).34 Likewise, the oral dosing of TG8–260 (25 mg/kg) in rats achieved about threefold higher concentration in the brain than the potency of the molecule.33 These data guided us for dosing in the current FPI studies. Animals were formally randomized for treatment with the vehicle or TG8–260 after injury and were housed with identically treated (i.e., TG8–260 or vehicle) animals until electrode implantation.

Seizure Identification and Monitoring

Acquisition of ECoG was done continuously for 2 days after 8 weeks of injury, as described previously.9,31,32 Any effect on the post-traumatic epileptic syndrome, 8 weeks post-injury could be accredited to the overall disease instead of any immediate antiseizure effect of the drug. Rats were attached to an amplifier headstage. Neurodata 12 or an M15 amplifier (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) was used to amplify and filter the brain electrical activity, which were acquired at 600 Hz per channel using SciWorks 4.1 or Experimenter V3 software (Datawave Technologies Inc., Longmont, CO) and DT3010 acquisition boards (DataTranslation Inc., Marlboro, MA). Videos were recorded in digital format. One or two cages were monitored by a single camera (one animal per cage).

Data analysis was performed in a blind fashion. Analysis was done using Matlab (MathWorks inc., Natick, MA) and scrolled manually offline. The onset of seizure was identified using (1) focal trains of spikes, lasting about 150 ms, with duration of more than 1 s above the baseline; (2) an acute increase in spectral power in the theta-band above the baseline12,35,36 and (3) stereotyped ictal behavioral changes that occur simultaneously, as described previously.37 Further, based on the clinical practice of investigating abnormal neuronal activities along with behavioral signs37−39 a single seizure included any event occurring within 3 s of each other. We classified spreading seizures (Sp) and nonspreading seizures (N-Sp) based on the number of electrodes that detected the seizure, as previously defined and described.12,32,37,40

The parameters collected from each seizure were: (1) onset time, (2) duration, and (3) ECoG channel(s) at the seizure commencement and spread. The factors used for assessment included seizure incidence (proportion of rats that exhibited seizures), comparison of seizure frequency (events/h), and time spent seizing (s/h) in TG8–260-treated rats and vehicle-treated controls.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as described previously.41,42 Briefly, the total RNA from brain tissues was isolated and purified with the Zymo Research Quick-RNA miniprep kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Zymo Research, CA). The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 1 μg of total RNA and 200 units of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), as per manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed by mixing 5 μL of 10× diluted cDNA, 0.1–0.5 μM primers (Table 1), and B-R iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Quanta, Gaithersburg, MD) to a final volume of 20 μL in an iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. The geometric mean of cycle thresholds for β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control for relative quantification. The analysis of qRT-PCR data was performed by subtracting the geometric mean of the two internal control genes from the measured cycle threshold value obtained from the log phase of the amplification curve of each gene of interest. The fold increase of each gene of interest was estimated for each treatment relative to the amount of RNA found in the sample from the control animal using the 2ΔΔCT method.

Table 1. Primers for mRNA Expression Study.

| list of primers |

|---|

| β-ACTIN-Rat-FP 5′ CCAACCGTGAAAAGATGACC 3′ |

| β-ACTIN-Rat-RP 5′ ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA 3′ |

| GAPDH-Rat-FP 5′ GGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAAC 3′ |

| GAPDH-Rat-RP 5′ CCTTGACTGTGCCGTTGAA 3′ |

| COX-2-Rat-FP 5′ ACCAACGCTGCCACAACT 3′ |

| COX-2-Rat-RP 5′ GGTTGGAACAGCAAGGATTT 3′ |

| COX-1-Rat-FP 5′ TGGATGGAGAGGTGTACCCA 3′ |

| COX-1-Rat-RP 5′ AGCAAGTCACACACACGGTT 3′ |

| EP-2-Rat-FP 5′ TGCGGATTGTCTGGCAGTAG 3′ |

| EP-2-Rat-RP 5′ CTCGGAGGTCCCACTTTTCC 3′ |

| IL-1β-Rat-FP 5′ CAGGAAGGCAGTGTCACTCA 3 |

| IL-1β-Rat-RP 5′ TCCCACGAGTCACAGAGGA 3′ |

| IL-6-Rat-FP 5′ AACTCCATCTGCCCTTCAGGAACA 3′ |

| IL-6-Rat-RP 5′ AAGGCAGTGGCTGTCAACAACATC 3′ |

| mPGES1-Rat-FP 5′ CTGCAGGAGTGACCCAGATG 3′ |

| mPGES1-Rat-RP 5′ GGTTGGGTCCCAGGAATGAG 3′ |

| TNf-α-Rat-FP 5′ CGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC 3′ |

| TNf-α-Rat-RP 5′ GGTTGTCTTTGAGATCCATGC 3′ |

| Casp1-Rat-FP 5′ CTGGAGCTTCAGTCAGGTCC 3′ |

| Casp1-Rat-RP 5′ CTTGAGGGAACCACTCGGTC 3′ |

| GFAP-Rat-FP 5′ CATCTCCACCGTCTTTACCAC 3′ |

| GFAP-Rat-RP 5′ AACCGCATCACCATTCCTG 3′ |

| CD11b-Rat-FP 5′ GAGCATCAGTAGCCAGCAT 3′ |

| CD11b-Rat-RP 5′ CCGTCCATTGTGAGATCCTT 3′ |

| lba1-Rat-FP 5′ TCGATATCTCCATTGCCATTCAG 3″ |

| lba1-Rat-RP 5′ GATGGGATCAAACAAGCACTTC 3′ |

| NOX2-GP91Ph-Rat-FP 5′ TGTGACAATGCCACCAGTCT 3′ |

| NOX2-GP91Ph-Rat-RP 5′ TCTTGCATCTGGGTCTCCA 3′ |

Protein Extraction and Western Blot

The extraction and analysis of protein from tissue samples were performed, as described previously.41,43,44 The samples from animals were homogenized in 10 volumes of RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove nuclei and cell debris. The supernatant was subsequently quantified using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the protein samples were separated using 4–16% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gel and electroblotted onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked for 1H at room temperature with Odyssey blocking solution (LI-COR) and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies for COX-2 (1:2000; abcam), NOX2 (1:1000, abcam), and GAPDH (1: 10,000; Calbiochem), followed by 1H incubation with polyclonal IRDye secondary antibodies 680LT and 800CW (1:15,000; LI-COR). The blots were imaged by a Bio-Rad imaging system. Quantification using Image Lab software (Bio-Rad) with samples normalized to GAPDH levels for loading control was performed.

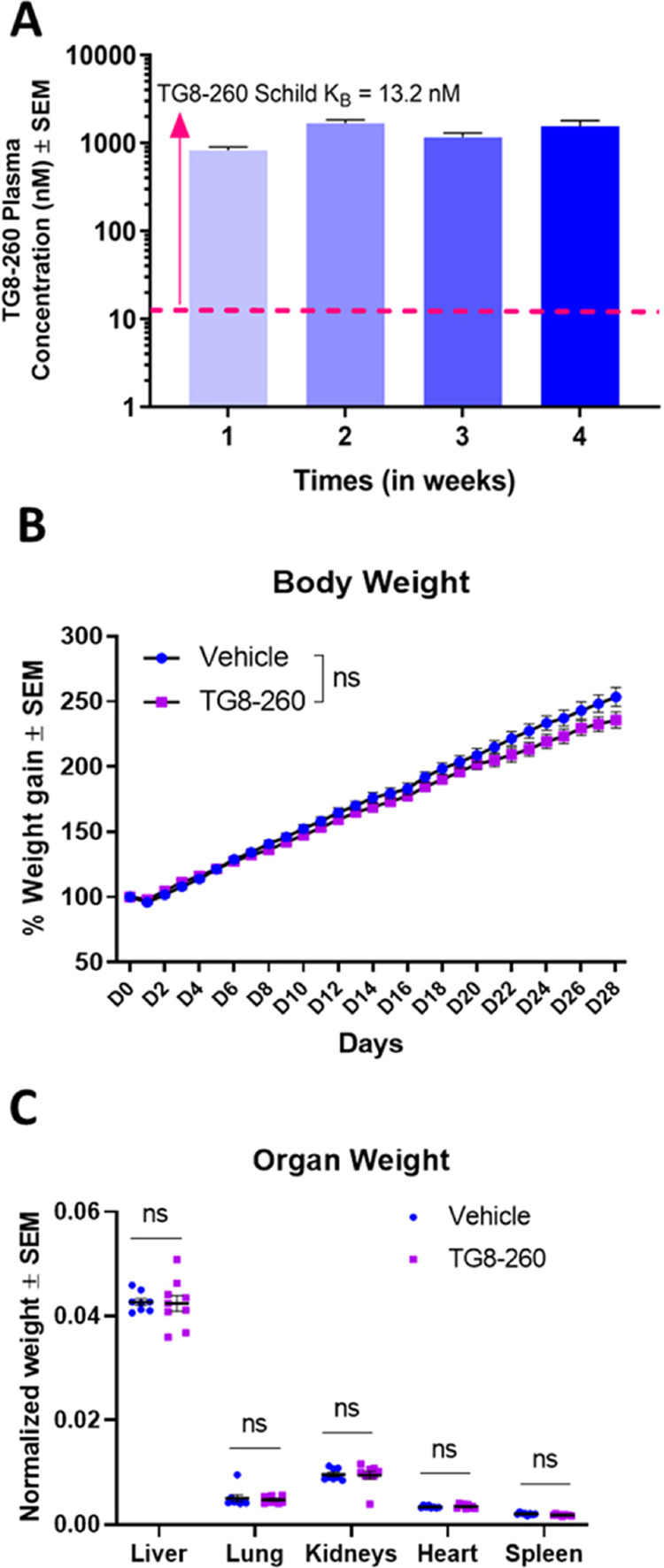

TG8–260 Dosing for Toxicity Measurement

To determine the in vivo safety of TG8–260 and its concentrations in plasma, SD rats were induced FPI and treated with either TG8–260 (n = 9) or vehicle (n = 8) for 4 weeks. Treatment with TG8–260 (25 mg/kg) or the vehicle (5% N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), 5% solutol HS-15, and 90% saline, 1 mL/kg) began 4 h after FPI, twice daily. Blood was collected from the tail vein at 1, 2, and 3 weeks after FPI injury and via cardiac puncture immediately prior to sacrifice 4 weeks after injury. In all cases, blood samples were obtained 8 h after the first dose of the day (morning dose). On the day of sacrifice, animals were deeply anesthetized 8 h after the morning dose. Blood was drawn from the heart of TG8–260-treated rats, and animals were rapidly perfused with 50 mL of ice-cold saline and 200 mL of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Vehicle-treated animals were treated identically, except that no blood was drawn. Following perfusion, heart, lung, liver, kidneys, and spleen were dissected from each rat, blotted, weighed, and transferred to 10% neutral formalin for further analysis (if needed). A comparison of the rat body weights and the macroscopic conditions of the organs and their weights from the TG8–260- and vehicle-treated rats provided a preliminary assessment of safety/toxicity of subchronic exposure to TG8–260 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Oral dosing of TG8–260 in SD rats achieves high plasma concentration and modest impact on body weight and no organ toxicity. Male SD rats were dosed for 4 weeks with TG8–260 (25 mg/kg, B.I.D.). (A) Blood was drawn weekly, 8 h after the morning dose, for concentration analysis in plasma. (B) Rats were weighed every day for 28 days. (C) On day 28, rats were euthanized, and organs were collected, blotted, and weighed and normalized to body weights to determine the preliminary toxic effect of TG8–260. Two-way repeated measures of ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparison test were applied for the analysis of body weights, and multiple unpaired t test with Holm–Sidak correction was applied for the analysis of organ weights (Prism 9.0). p<0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism (9.0.2) was used for mRNA and protein expression analysis. For mRNA analysis, Brown-Forsyth ANOVA test with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was utilized, whereas one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used for protein expression analysis. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

The primary analysis of the ECoG data was conducted blind to the identity of individual data files, which were assigned arbitrary numeric codes until the analysis was complete. Statistical analyses of the ECoG data were performed using R (v. 4.0.2). Fisher exact tests, Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, and t tests were all performed using the stats package, and Mann–Whitney tests were performed using the coin package. All tests were one-tailed.

Results

FPI Leads to Increased mRNA Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators, Glial Markers, and Oxidative Stress Markers in the Hippocampus and Cortex of Rats

In ipsilateral cortex, the mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators COX-1 (Figure 1A), COX-2 (Figure 1B), EP2 (Figure 1C), IL-1β (Figure 1D), IL-6 (Figure 1E), mPGES1 (Figure 1F), and TNF-α (Figure 1G) was significantly upregulated 3 h post-FPI, with the expression returning to baseline level by 24 h post-FPI. The expressions of astrocyte marker GFAP (Figure 1I) and microglial marker CD11b (Figure 1J) were significantly elevated 3 h post-FPI, with the expression further increasing by 24 h post-FPI. The oxidative stress marker NOX2 showed a significant elevation in expression 8 h post-FPI, with a further increase in expression by 24 h (Figure 1L). Interestingly, CD11b, a marker of activated microglia, increased over time, while IBA1, a marker of resting microglia, transiently decreased at 3 h and then restored to sham levels through 24 h (Figure 1J,K). FPI resulted in the reduction in the expression of proinflammatory mediator caspase-1 after 3 h of FPI, which came up to the basal level by 8 h post-FPI (Figure 1H). The detailed expression profile in ipsilateral cortex is provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Effect of rpFPI on gene expression in ipsilateral cortex. Inflammatory mediators were upregulated within 3 h (3 h) post-FPI compared to sham animals: (A) COX-1 (1.29-fold), (B) COX-2 (3.2-fold), (C) EP2 (2.4-fold), (D) IL-1β (92-fold), (E) IL-6 (10.9-fold), (F) mPGES1 (22.5-fold), and (G) TNF-α (19.4-fold) with expression returning to basal levels by 24 h (24 h) post-rpFPI. (H) Caspase-1, a critical player in inflammatory process, was downregulated (0.34-fold) at 3 h post-rpFPI, with the expression returning to basal level by 8 h The marker of astrogliosis (I) GFAP showed significant increase in expression starting 3 h (0.65-fold) and continued at an elevated level through 24 h (3.5-fold) post-rpFPI. Microglial expression markers (J) CD11b and (K) IBA1 showed differential patterns with CD11b expression elevated by 3 h (1.5-fold) and remaining high through 24 h (3.3-fold) post-rpFPI, whereas IBA1 expression showed reduction at 3 h (0.45-fold), with the expression returning to basal level 8 h post-rpFPI. ROS-producing enzyme NOX2 (L) elevated at 8 h (0.58-fold) post-rpFPI and remained elevated through 24 h (1-fold) post-injury. Sham (n = 16), 3, 8, 16, 24 h (n = 7), and 12 h (n = 8). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for analysis, p <0.05 was considered significant; * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Table 2. mRNA Expression in Ipsilateral Cortex of Ratsa.

| expression

fold change from sham |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene | 3 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 24 h |

| COX-1 | 0.29, p < 0.05 | –0.28, p < 0.05 | ns | –0.3, p < 0.05 | ns |

| COX-2 | 3.2, p < 0.0001 | ns | 0.5, p < 0.01 | ns | ns |

| EP2 | 2.4, p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| IL-1β | 92, p < 0.0001 | 10.7, p < 0.05 | 4.7, p < 0.01 | 1.8, p < 0.05 | ns |

| IL-6 | 10.9, p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| mPGES1 | 22.5, p < 0.001 | 7.6, p < 0.05 | 3, p < 0.001 | 1.2, p < 0.05 | ns |

| TNF-α | 19.4, p < 0.0001 | 5, p < 0.01 | 4.9, p < 0.0001 | 2.2, p < 0.001 | ns |

| caspase-1 | –0.34, p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| GFAP | 0.65, p < 0.05 | 2, p < 0.001 | 3.1, p < 0.0001 | 3.7, p < 0.0001 | 3.5, p < 0.01 |

| CD11b | 0.53, p < 0.05 | 2.4, p < 0.001 | 4.2, p < 0.0001 | 4.1, p < 0.0001 | 3.3, p < 0.001 |

| IBA1 | –0.45, p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| NOX2 | ns | 0.58, p < 0.01 | 0.7, p < 0.01 | 0.61, p < 0.05 | 1, p < 0.05 |

ns = not statistically significant.

In ipsilateral hippocampus, FPI resulted in a significant elevation in the expression of COX-2 (Figure 2B), IL-1β (Figure 2D), IL6 (Figure 2E), mPGES1 (Figure 2F), and TNF-α (Figure 2G) 3 h post-FPI. The expression levels were back to baseline by 24 h post-FPI. However, contrary to the effect in ipsilateral cortex, the inflammatory mediator COX-1 (Figure 2A) showed a significant decrease in expression after FPI, whereas EP2 (Figure 2C) expression remained unchanged. As in ipsilateral cortex, the astrocytic marker GFAP (Figure 2I) in hippocampus was gradually elevated from 3 to 24 h post-FPI. Similarly, the microglial marker CD11b (Figure 2J) was significantly elevated beginning 3 h post-FPI and remained so through 24 h post-FPI, while the microglial marker IBA1 (Figure 2K) was transiently downregulated at 3 h post-FPI, with the expression returning to the baseline by 8 h post-FPI. The ROS-producing and oxidative stress-causing enzyme NOX2 (Figure 2L) showed a significant increase in expression 8 h post-FPI, with the expression remaining elevated 24 h post-FPI. The expression of proinflammatory mediator caspase-1 (Figure 2H) was reduced 3 h post-FPI and returned to baseline 8 h post-FPI. The detailed expression profile of ipsilateral cortex is provided in Table 3. Overall, except COX-1 and EP2, the expression of other genes is similar in both ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus post-FPI.

Figure 2.

Effect of rpFPI on gene expression in ipsilateral hippocampus: inflammatory mediators were upregulated within 3 h post-FPI compared to sham animals. (B) COX-2 (7.7-fold), (D) IL-1β (299-fold), (E) IL-6 (12.4-fold), (F) mPGES1 (67-fold), (G) TNF-α (29-fold), with expression returning to basal levels by 24 h post-rpFPI. Inflammatory marker (A) COX-1 showed a decrease in expression beginning 3 h (0.27-fold) post-rpFPI and remained low through 24 h (0.36-fold), whereas(C) EP2 and (H) caspase-1 showed no alteration in expression. Marker of astrogliosis (I) GFAP showed significant increase in expression starting 3 h (0.7-fold) and continued at an elevated level through 24 h (4.5-fold) post-rpFPI. Microglial expression markers (J) CD11b and (K) IBA1 showed a differential pattern with CD11b expression elevated by 3 h (0.9-fold) and remaining high through 24 h (6-fold) post-rpFPI, whereas IBA1 expression showed reduction at 3 h (0.29-fold), with expression returning to basal level 8 h post-rpFPI. Marker of oxidative stress (L) NOX2 had elevated expression 12 h (3-fold) post-rpFPI and remained elevated through 24 h (7-fold) after the injury. Sham (n = 16), 3 h, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h (n = 7), 12 h (n = 8). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for analysis. p<0.05 was considered significant; * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Table 3. mRNA Expression in Ipsilateral Hippocampus of Ratsa.

| expression

fold change from sham |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene | 3 h | 8 h | 12 h | 16 h | 24 h |

| COX-1 | –0.27, p < 0.05 | –0.41, p < 0.001 | –0.39, p < 0.0001 | –0.48, p < 0.0001 | –0.36, p < 0.0001 |

| COX-2 | 7.68, p < 0.01 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| EP2 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| IL-1β | 299, p < 0.0001 | 46, p < 0.01 | 18, p < 0.05 | 10, p < 0.05 | ns |

| IL-6 | 12.4, p < 0.0001 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| mPGES1 | 67, p < 0.001 | 19, p < 0.05 | 7.8, p < 0.01 | ns | ns |

| TNF-α | 29, p < 0.001 | 7.2, p < 0.01 | 7, p < 0.001 | 3.7, p < 0.0001 | ns |

| caspase-1 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| GFAP | 0.7, p < 0.05 | 2.4, p < 0.0001 | 3.2, p < 0.001 | 2.9, p < 0.001 | 4.5, p < 0.001 |

| CD11b | 0.9, p < 0.01 | 3.8, p < 0.001 | 4.8, p < 0.001 | 4.9, p < 0.001 | 6, p < 0.001 |

| IBA1 | –0.29, p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| NOX2 | ns | ns | 3, p < 0.05 | 2.3, p < 0.01 | 7, p < 0.001 |

ns = not statistically significant.

FPI Leads to Increased Inflammatory Response in Hippocampus and Cortex of Rats

We selected two protein markers, COX-2 (neuroinflammation) and NOX2 (oxidative stress), to evaluate in FPI brains. The expression of COX-2 was significantly increased in ipsilateral cortex (Figure 3A) and ipsilateral hippocampus (Figure 3B) in rats post-FPI. This increase in expression was observed 3 h post-FPI in the hippocampus (p < 0.05) and 24 h post-FPI in the cortex (p < 0.05) (Figure 33EC and ). The expression of NOX2 (Figure 3A,B) was significantly reduced 3 h post-FPI (p < 0.01) in ipsilateral hippocampus and remained reduced at 24 h (p < 0.05) (Figure 3F); however, there was no change in NOX2 protein expression in ipsilateral cortex in rats post-FPI (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Effect of rpFPI on the expression of COX2 and NOX2 proteins: representative western blot showing the expression of COX2 and NOX2 in ipsilateral cortex (A) and ipsilateral hippocampus (B). COX2 expression is significantly elevated 3 h post-FPI in ipsilateral hippocampus (E) (p < 0.05, n = 6) and 24 h post-FPI in ipsilateral cortex (C) (p < 0.05, n = 6). NOX2 expression showed a significant decrease at 3 h (p < 0.01, n = 6) which persisted even at 24 h post-FPI (p < 0.05, n = 6) in ipsilateral hippocampus (F), whereas no differential expression was observed in the protein level of NOX2 in ipsilateral cortex post-FPI (D) (n = 6). Data were normalized to control (NTC) expression, where naïve animals were used as control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for analysis. p <0.05 was considered significant; * < 0.05, ** < 0.01.

EP2 Antagonist TG8–260 Reduces the Duration of FPI-Induced Post-Traumatic Seizures in Rats

Others and we reported that the EP2 receptor acts downstream of COX-2 and carries forward a major inflammatory signaling in acute neuroinflammatory models.20 We also reported the TG8–260 structure, potency against EP2 receptor (Schild KB = 13.2 nM), and its anti-inflammatory activity in an in vitro cellular model33 and the anti-inflammatory actions in the brain of an acute neuroinflammatory mouse model, status epilepticus.34 Here, we asked whether this specific antagonist of EP2 is beneficial in the rat FPI model. Rats that were given the EP2 antagonist TG8–260 beginning 30 min post-FPI, twice daily, for 5 days (total 10 doses) showed a trend of reduced seizure incidence (Figure 4A), seizure frequency (Figure 4B), and time seizing (Figure 4C), but the reductions observed did not reach statistical significance. However, a leftward shift in the distribution of seizure durations (toward shorter seizures) in TG8–260-treated animals (Figure 4D) was statistically significant (p = 0.00345, two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). This result indicates that TG8–260 treatment has no effect on brief seizures (<2 s duration) but has a stronger effect on longer duration seizures, which overall would reduce the seizure burden.

Figure 4.

Effect of TG8–260 (25 mg/kg) on post-FPI seizures: (A) Rats treated for 5 days with TG8–260 showed a trend of reduction in seizure incidence over the succeeding 4 weeks. Seizure incidences were reduced for nonspreading focal seizures (N-Sp), spreading seizures (Sp), and total seizures (All). In the case of seizure frequency (B), the treatment of rats with TG8–260 post-FPI showed nonsignificant reduction in Sp and All seizures. The total time of seizure (C) also showed a nonsignificant reduction in Sp and All seizures in rats treated with TG8–260. (D) When comparing seizure duration as an empirical cumulative distribution function, TG8–260 treatment resulted in a significant reduction in the distribution of seizure duration; p = 0.00345 (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). The effect of TG8–260 was more pronounced for longer seizures.

EP2 Antagonist TG8–260 Does Not Have any Adverse Effect on Body Weight and Organ Weight of Rats

Twice daily dosing of TG8–260 at 25 mg/kg achieved a plasma concentration 100-fold higher than the Schild KB value (Figure 5A), but this did not have any adverse effect on the body weight (Figure 5B) or organ weight of rats (Figure 5C). Toxic molecules are expected to impact the weights of vital organs; therefore, we used the organ-to-body weight ratio as a measure of preliminary toxicity by TG8–260, with an intention to follow-up through organ histology if there was a difference found in the weights.45,46 It is worth noting that we recently published the pharmacokinetic data for this compound that showed a brain-to-plasma ratio of 0.04, but its concentration in the brain was still about eightfold higher than its Schild potency.33,34 Therefore, we anticipate about three—to fourfold higher concentration in the brain than the potency of the molecule in our efficacy studies (represented in Figure 4).

Discussion

In this study, we show a rapid increase in the mRNA expression of proinflammatory markers following FPI at 3 h post-injury, which subsided to basal levels by 24 h post-injury compared to sham control animals. On the other hand, the markers of activated astrocytes, microglia, and oxidative stress started increasing by 8 h post-injury and remained upregulated through 24 h post-injury. This transcriptional expression pattern was similar in both ipsilateral cortex and ipsilateral hippocampus, with the protein analysis showing increased expression of inflammatory marker (COX-2) but not of oxidative stress-causing enzyme (NOX2) marker. Upon treatment with an EP2 receptor antagonist (TG8–260), we observed a trend toward reduced post-traumatic seizure incidence in rats, but no effect was seen on seizure frequency and time seizing. However, interestingly, a significant leftward shift (toward shorter seizures) in the distribution of seizure durations was observed in rats treated with EP2 antagonist compared to vehicle-treated controls. The TG8–260 effect was the largest for the longer duration post-traumatic seizures. Although this effect was modest in magnitude, the fact that it was detected weeks after the end of drug treatment suggests it to be a durable disease-modifiying effect that could potentially be improved with different lengths, timings, or intensities (dose) of treatment.

The rpFPI model of PTE in young rats is well established, mimics the key histopathological and pathophysiological effects of head injury in humans, and has been used extensively to study epilepsy.12,31,32,37,40,47 Neuroinflammation has been detected in brain after TBI.48−52 Many studies have shown that inflammatory markers are induced in the models of TBI,53−56 with the effect predominantly seen in the ipsilateral side of the brain.53,56 However, these studies only examine the expression of inflammatory markers, days if not months after TBI. Our study shows that the markers of neuroinflammation are upregulated within 3 h of FPI while the markers of glial activation and oxidative stress being upregulated by 8 h post-injury.

One interesting observation we made in our study is that the microglial markers Iba1 and CD11b were differentially expressed after FPI. We saw a significant increase in the level of CD11b in hippocampus, whereas Iba1 expression was reduced 3 h post-FPI and reverted to basal level later in the study. This observation may point toward either the activation of resting microglia in the brain post-FPI or disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) leading to the infiltration of monocytes into the brain post-FPI. This has been known to happen in the models of brain injury, where peripheral monocytes invade the brain, resulting in the accumulation of brain with monocytes that are CD11b+.57,58 Another interesting observation we made was the expression pattern of Iba1 and CD11b in the rpFPI rat model compared to the pilocarpine-SE mouse model.59 Iba1 expression was reduced immediately following rpFPI and pilocarpine-SE. However, the expression of CD11b was immediately upregulated in rpFPI rats, whereas in pilocarpine-SE mice, there was no induction of CD11b until 24 h post-treatment, indicating that rpFPI leads to an immediate disruption of BBB which allows the entry of circulating macrophages, whereas BBB disruption is delayed in pilocarpine-induced SE. Several studies including our own point to the hypothesis that neuroinflammatory molecules (cytokines and glial) are associated with synapse loss, neuronal death, BBB compromise, and monocyte entry into the brain, which lead to cognitive and behavioral deficits;14 however, the exact correlation between the brain inflammatory mediators and the emergence of post-traumatic seizures is to be established rigorously, although a recent study by Golub and Reddy10 shows that GFAP and Iba1 expression is induced on day 1 and stays upregulated until 120 days post-CCI injury in mice, which develop post-traumatic seizures, suggesting there might be correlation between glial activation and the post-traumatic seizures.

Upregulation of NOX2 post-TBI has been reported by many studies,60−62 with the knockout of NOX2 being beneficial in different models of TBI.63−65 Furthermore, various beneficial treatments for TBI are thought to be acting via the suppression of NOX2.24,66−74 Our results showed an elevated mRNA expression of NOX2 in both ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus within 24 h after rpFPI. However, NOX2 protein levels were unchanged in ipsilateral cortex but showed significantly reduced expression in ipsilateral hippocampus. Clearly, further studies are needed to observe the effects of rpFPI on NOX2 expression at time points later than 24 h after FPI to get a better understanding of the temporal expression of this ROS-generating enzyme.

We observed an increase in mRNA expression of COX-2 in ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus of rats which was confirmed at the protein level, with increases observed as early as 3 h after injury in ipsilateral hippocampus and after 24 h in ipsilateral cortex. Given the well documented adverse events associated with marketed COX-2 inhibitor drugs,27,30 we targeted COX-2 downstream the PGE2 receptor EP2 with the selective small-molecule antagonist TG8–260,33 which reduces neuroinflammation and gliosis after status epilepticus in rats.34 Although we observed a modest decrease in seizure duration, the trend of reduced seizure incidence was encouraging and lays a foundation for more expansive studies involving an optimized, perhaps more highly brain-permeable, EP2 antagonist in the rpFPI model. Additional studies are also needed to determine whether the EP2 antagonist reduces inflammatory and oxidative stress markers post-FPI insult, as it does in a rat status epilepticus model.34

The relationship between the neuroinflammatory cascade and oxidative stress signaling suggests a cross talk among these pathways, and together they can exacerbate the epileptogenic processes.22 Therapeutic approaches targeting the key enzymes such as COX-2 or NOX2, or PGE2 receptor EP2 with small-molecule inhibitors will be a novel strategy to mitigate epileptogenesis, provided we understand the temporal expression of these markers after acute FPI. Our study shows the emergence of neuroinflammatory mediators including COX-2 (mRNA and protein) and oxidative stress-causing enzyme NOX2 (mRNA) in the rpFPI model within the first 24 h of FPI, suggesting treatments beginning 1–3 h after TBI injury until 24 h should provide benefits.

Significance Statement

Our knowledge of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress immediately following TBI is limited. We utilized the rpFPI model of PTE to study the molecular markers associated with neuroinflammation and oxidative stress at various time points up to 24 h post-FPI. Furthermore, we treated rats with an anti-inflammatory EP2 antagonist (TG8–260) post-rpFPI, which resulted in the reduction of seizure duration, providing a proof of concept for additional studies to examine anti-inflammatory strategies against PTE.

Author Present Address

⊥ Center for Innovative Drug Discovery, The University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas 78249, United States

Author Present Address

# Department of Biotechnology, School of Science, GITAM (Deemed to be University), Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh 530025, India

Author Contributions

T.G. and R.D’.A. designed the overall research. C.E., V.R., and R.D participated in experimental design. V.R., C.E., J.F., A.B., and R.A. performed the experiments. V.R. and C.E. were involved in data collection. V.R., C.E., T.G., and R.D. analyzed the data. T.G. and V.R. wrote the manuscript, and all others contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants: NINDS, R21/R33 [NS10167] (T.G.), and NIA, U01 [AG052460] (T.G.).

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Authors T.G. and R.D. are founders of, and have equity in, Pyrefin Inc., which has licensed EP2 technology from Emory University in which T.G., R.D., and R.A. are inventors.

Notes

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted according to the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) and were approved by the University of Washington Animal Care and Use Committee.

Notes

All data analyzed and presented in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- French J. A.; Pedley T. A. Clinical practice. Initial management of epilepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 166–176. 10.1056/NEJMcp0801738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein D. H. Epilepsy after head injury: an overview. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 4–9. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin N. R. Preventing and treating posttraumatic seizures: the human experience. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 10–13. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caveness W. F.; Portera A.; Scheffner D. Epilepsy, a product of trauma in our time. Epilepsia 1976, 17, 207–215. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1976.tb03398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh M. J.; Orman J. A.; Jaramillo C. A.; Salinsky M. C.; Eapen B. C.; Towne A. R.; Amuan M. E.; Roman G.; McNamee S. D.; Kent T. A.; McMillan K. K.; Hamid H.; Grafman J. H. The prevalence of epilepsy and association with traumatic brain injury in veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015, 30, 29–37. 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymont V.; Salazar A. M.; Lipsky R.; Goldman D.; Tasick G.; Grafman J. Correlates of posttraumatic epilepsy 35 years following combat brain injury. Neurology 2010, 75, 224–229. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e6d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G. H.; Feeney D. M.; Caveness W. F.; Dillon D.; Kistler J. P.; Mohr J. P.; Rish B. L. Prognostic factors for the occurrence of posttraumatic epilepsy. Arch. Neurol. 1983, 40, 7–10. 10.1001/archneur.1983.04050010027006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub V. M.; Reddy D. S. Post-Traumatic Epilepsy and Comorbidities: Advanced Models, Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Novel Therapeutic Interventions. Pharmacol. Rev. 2022, 74, 387–438. 10.1124/pharmrev.121.000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman C. L.; Fender J. S.; Temkin N. R.; D’Ambrosio R. Optimized methods for epilepsy therapy development using an etiologically realistic model of focal epilepsy in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 264, 150–162. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub V. M.; Reddy D. S. Contusion brain damage in mice for modelling of post-traumatic epilepsy with contralateral hippocampus sclerosis: Comprehensive and longitudinal characterization of spontaneous seizures, neuropathology, and neuropsychiatric comorbidities. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 348, 113946 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy D. S.; Golub V. M.; Ramakrishnan S.; Abeygunaratne H.; Dowell S.; Wu X. A Comprehensive and Advanced Mouse Model of Post-Traumatic Epilepsy with Robust Spontaneous Recurrent Seizures. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e447 10.1002/cpz1.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R.; Fairbanks J. P.; Fender J. S.; Born D. E.; Doyle D. L.; Miller J. W. Post-traumatic epilepsy following fluid percussion injury in the rat. Brain 2004, 127, 304–314. 10.1093/brain/awh038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A.; French J.; Bartfai T.; Baram T. Z. The role of inflammation in epilepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011, 7, 31–40. 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A.; Friedman A.; Dingledine R. J. The role of inflammation in epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology 2013, 69, 16–24. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesman I. R.; Schilling J. M.; Shapiro L. A.; Kellerhals S. E.; Bonds J. A.; Kleschevnikov A. M.; Cui W.; Voong A.; Krajewski S.; Ali S. S.; Roth D. M.; Patel H. H.; Patel P. M.; Head B. P. Traumatic brain injury enhances neuroinflammation and lesion volume in caveolin deficient mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 39. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock T.; Morganti-Kossmann M. C. The role of markers of inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 18. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; Dingledine R. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the crosshairs of anti-inflammation, anti-cancer, and neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 413–423. 10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S. M.; Rothwell N. J.; Gibson R. M. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S232–S240. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L. Role of inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2005, 18, 315–321. 10.1097/01.wco.0000169752.54191.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Chen D.; Ganesh T.; Varvel N. H.; Dingledine R. The COX-2/prostanoid signaling cascades in seizure disorders. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 1–13. 10.1080/14728222.2019.1554056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel N. H.; Neher J. J.; Bosch A.; Wang W.; Ransohoff R. M.; Miller R. J.; Dingledine R. Infiltrating monocytes promote brain inflammation and exacerbate neuronal damage after status epilepticus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, E5665–E5674. 10.1073/pnas.1604263113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman C. L.; D’Ambrosio R.; Ganesh T. Modulating neuroinflammation and oxidative stress to prevent epilepsy and improve outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Neuropharmacology 2020, 172, 107907 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauletti A.; Terrone G.; Shekh-Ahmad T.; Salamone A.; Ravizza T.; Rizzi M.; Pastore A.; Pascente R.; Liang L. P.; Villa B. R.; Balosso S.; Abramov A. Y.; van Vliet E. A.; Del Giudice E.; Aronica E.; Patel M.; Walker M. C.; Vezzani A. Targeting oxidative stress improves disease outcomes in a rat model of acquired epilepsy. Brain 2019, 142, e39 10.1093/brain/awz130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Luo L. An Effective NADPH Oxidase 2 Inhibitor Provides Neuroprotection and Improves Functional Outcomes in Animal Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1097–1106. 10.1007/s11064-020-02987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon C. P.; Cannon P. J. Physiology. COX-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk. Science 2012, 336, 1386–1387. 10.1126/science.1224398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzin J. Clinical trials. Nail-biting time for trials of COX-2 drugs. Science 2004, 306, 1673–1675. 10.1126/science.306.5702.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosser T.; Yu Y.; Fitzgerald G. A. Emotion recollected in tranquility: lessons learned from the COX-2 saga. Annu. Rev. Med. 2010, 61, 17–33. 10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh T. Prostanoid receptor EP2 as a therapeutic target. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4454–4465. 10.1021/jm401431x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Jiang J.; Ganesh T.; Yang M. S.; Lelutiu N.; Gueorguieva P.; Dingledine R. Cyclooxygenase-2 in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 17–25. 10.1111/epi.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan K. M.; Lawson J. A.; Fries S.; Koller B.; Rader D. J.; Smyth E. M.; Fitzgerald G. A. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science 2004, 306, 1954–1957. 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R.; Eastman C. L.; Darvas F.; Fender J. S.; Verley D. R.; Farin F. M.; Wilkerson H. W.; Temkin N. R.; Miller J. W.; Ojemann J.; Rothman S. M.; Smyth M. D. Mild passive focal cooling prevents epileptic seizures after head injury in rats. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 73, 199–209. 10.1002/ana.23764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman C. L.; Verley D. R.; Fender J. S.; Temkin N. R.; D’Ambrosio R. ECoG studies of valproate, carbamazepine and halothane in frontal-lobe epilepsy induced by head injury in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 224, 369–388. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaradhi R.; Mohammed S.; Banik A.; Franklin R.; Dingledine R.; Ganesh T. Second-Generation Prostaglandin Receptor EP2 Antagonist, TG8-260, with High Potency, Selectivity, Oral Bioavailability, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 118–133. 10.1021/acsptsci.1c00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Amaradhi R.; Banik A.; Jiang C.; Abreu-Melon J.; Wang S.; Dingledine R.; Ganesh T. A Novel Second-Generation EP2 Receptor Antagonist Reduces Neuroinflammation and Gliosis After Status Epilepticus in Rats. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1207–1225. 10.1007/s13311-020-00969-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler T.; Ichise M.; Teich A. F.; Gerard E.; Osborne J.; French J.; Devinsky O.; Kuzniecky R.; Gilliam F.; Pervez F.; Provenzano F.; Goldsmith S.; Vallabhajosula S.; Stern E.; Silbersweig D. Imaging inflammation in a patient with epilepsy due to focal cortical dysplasia. J. Neuroimaging 2013, 23, 129–131. 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda A.; Hirasawa K.; Kinoshita M.; Hitomi T.; Matsumoto R.; Mitsueda T.; Taki J. Y.; Inouch M.; Mikuni N.; Hori T.; Fukuyama H.; Hashimoto N.; Shibasaki H.; Takahashi R. Negative motor seizure arising from the negative motor area: is it ictal apraxia?. Epilepsia 2009, 50, 2072–2084. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R.; Hakimian S.; Stewart T.; Verley D. R.; Fender J. S.; Eastman C. L.; Sheerin A. H.; Gupta P.; Diaz-Arrastia R.; Ojemann J.; Miller J. W. Functional definition of seizure provides new insight into post-traumatic epileptogenesis. Brain 2009, 132, 2805–2821. 10.1093/brain/awp217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R.; Miller J. W. What is an epileptic seizure? Unifying definitions in clinical practice and animal research to develop novel treatments. Epilepsy Curr. 2010, 10, 61–66. 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2010.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. S.; Harding G.; Erba G.; Barkley G. L.; Wilkins A.; Photic- and pattern-induced seizures: a review for the Epilepsy Foundation of America Working Group. Epilepsia 2005, 46, 1426–1441. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.31405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R.; Fender J. S.; Fairbanks J. P.; Simon E. A.; Born D. E.; Doyle D. L.; Miller J. W. Progression from frontal-parietal to mesial-temporal epilepsy after fluid percussion injury in the rat. Brain 2004, 128, 174–188. 10.1093/brain/awh337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat V.; Wang S.; Sima J.; Bar R.; Liraz O.; Gundimeda U.; Parekh T.; Chan J.; Johansson J. O.; Tang C.; Chui H. C.; Harrington M. G.; Michaelson D. M.; Yassine H. N. ApoE4 Alters ABCA1 Membrane Trafficking in Astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9611–9622. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1400-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas A.; Banik A.; Chen D.; Flood K.; Ganesh T.; Dingledine R. Novel Microglia Cell Line Expressing the Human EP2 Receptor. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4280–4292. 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat V.; Goux W.; Piechaczyk M. c-Fos Protects Neurons Through a Noncanonical Mechanism Involving HDAC3 Interaction: Identification of a 21-Amino Acid Fragment with Neuroprotective Activity. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1165–1180. 10.1007/s12035-014-9058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel N. H.; Espinosa-Garcia C.; Hunter-Chang S.; Chen D.; Biegel A.; Hsieh A.; Blackmer-Raynolds L.; Ganesh T.; Dingledine R. Peripheral Myeloid Cell EP2 Activation Contributes to the Deleterious Consequences of Status Epilepticus. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 1105–1117. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2040-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey S. A.; Zidell R. H.; Perry R. W. Relationships between organ weight and body/brain weight in the rat: what is the best analytical endpoint?. Toxicol. Pathol. 2004, 32, 448–466. 10.1080/01926230490465874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazic S. E.; Semenova E.; Williams D. P. Determining organ weight toxicity with Bayesian causal models: Improving on the analysis of relative organ weights. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6625. 10.1038/s41598-020-63465-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. J.; Lifshitz J.; Marklund N.; Grady M. S.; Graham D. I.; Hovda D. A.; McIntosh T. K. Lateral fluid percussion brain injury: a 15-year review and evaluation. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 42–75. 10.1089/neu.2005.22.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immonen R.; Harris N. G.; Wright D.; Johnston L.; Manninen E.; Smith G.; Paydar A.; Branch C.; Grohn O. Imaging biomarkers of epileptogenecity after traumatic brain injury – Preclinical frontiers. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 123, 75–85. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein P.; Dingledine R.; Aronica E.; Bernard C.; Blumcke I.; Boison D.; Brodie M. J.; Brooks-Kayal A. R.; Engel J. Jr.; Forcelli P. A.; Hirsch L. J.; Kaminski R. M.; Klitgaard H.; Kobow K.; Lowenstein D. H.; Pearl P. L.; Pitkanen A.; Puhakka N.; Rogawski M. A.; Schmidt D.; Sillanpaa M.; Sloviter R. S.; Steinhauser C.; Vezzani A.; Walker M. C.; Loscher W. Commonalities in epileptogenic processes from different acute brain insults: Do they translate?. Epilepsia 2018, 59, 37–66. 10.1111/epi.13965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkov A.; Puhakka N.; Gupta S. D.; Vuokila N.; Broekaart D. W. M.; Anink J. J.; Heiskanen M.; Karttunen J.; van Scheppingen J.; Huitinga I.; Mills J. D.; van Vliet E. A.; Pitkanen A.; Aronica E. Increased expression of miR142 and miR155 in glial and immune cells after traumatic brain injury may contribute to neuroinflammation via astrocyte activation. Brain Pathol. 2020, 30, 897–912. 10.1111/bpa.12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missault S.; Anckaerts C.; Blockx I.; Deleye S.; Van Dam D.; Barriche N.; De Pauw G.; Aertgeerts S.; Valkenburg F.; De Deyn P. P.; Verhaeghe J.; Wyffels L.; Van der Linden A.; Staelens S.; Verhoye M.; Dedeurwaerdere S. Neuroimaging of Subacute Brain Inflammation and Microstructural Changes Predicts Long-Term Functional Outcome after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 768–788. 10.1089/neu.2018.5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet E. A.; Ndode-Ekane X. E.; Lehto L. J.; Gorter J. A.; Andrade P.; Aronica E.; Grohn O.; Pitkanen A. Long-lasting blood-brain barrier dysfunction and neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 145, 105080 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan H. H.; Wathen C. A.; Mathews N. D.; Hogue O.; Modic J. P.; Kundalia R.; Wyant C.; Park H. J.; Najm I. M.; Trapp B. D.; Machado A. G.; Baker K. B. Lateral cerebellar nucleus stimulation promotes motor recovery and suppresses neuroinflammation in a fluid percussion injury rodent model. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 1356–1367. 10.1016/j.brs.2018.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M. L.; Ritter A. C.; Failla M. D.; Boles J. A.; Conley Y. P.; Kochanek P. M.; Wagner A. K. IL-1beta associations with posttraumatic epilepsy development: a genetics and biomarker cohort study. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 1109–1119. 10.1111/epi.12628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glushakova O. Y.; Glushakov A. O.; Borlongan C. V.; Valadka A. B.; Hayes R. L.; Glushakov A. V. Role of Caspase-3-Mediated Apoptosis in Chronic Caspase-3-Cleaved Tau Accumulation and Blood-Brain Barrier Damage in the Corpus Callosum after Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 157–173. 10.1089/neu.2017.4999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komoltsev I. G.; Frankevich S. O.; Shirobokova N. I.; Volkova A. A.; Onufriev M. V.; Moiseeva J. V.; Novikova M. R.; Gulyaeva N. V. Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Loss in the Hippocampus Are Associated with Immediate Posttraumatic Seizures and Corticosterone Elevation in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5883. 10.3390/ijms22115883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H. K.; Ji K. M.; Kim B.; Kim J.; Jou I.; Joe E. H. Inflammatory responses are not sufficient to cause delayed neuronal death in ATP-induced acute brain injury. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13756 10.1371/journal.pone.0013756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K. A.; Yang M. S.; Jeong H. K.; Min K. J.; Kang S. H.; Jou I.; Joe E. H. Resident microglia die and infiltrated neutrophils and monocytes become major inflammatory cells in lipopolysaccharide-injected brain. Glia 2007, 55, 1577–1588. 10.1002/glia.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J.; Yang M. S.; Quan Y.; Gueorguieva P.; Ganesh T.; Dingledine R. Therapeutic window for cyclooxygenase-2 related anti-inflammatory therapy after status epilepticus. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 76, 126–136. 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Barrett J. P.; Alvarez-Croda D. M.; Stoica B. A.; Faden A. I.; Loane D. J. NOX2 drives M1-like microglial/macrophage activation and neurodegeneration following experimental traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 58, 291–309. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.07.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.; Jiang Y.; Liang W.; Wang Y.; Cao S.; Yan H.; Gao L.; Zhang L. miR-212-5p attenuates ferroptotic neuronal death after traumatic brain injury by targeting Ptgs2. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 78. 10.1186/s13041-019-0501-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Li Z.; Feng D.; Shen H.; Tian X.; Li H.; Wang Z.; Chen G. Involvement of Nox2 and Nox4 NADPH oxidases in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Free Radical Res. 2017, 51, 316–328. 10.1080/10715762.2017.1311015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. P.; Henry R. J.; Villapol S.; Stoica B. A.; Kumar A.; Burns M. P.; Faden A. I.; Loane D. J. NOX2 deficiency alters macrophage phenotype through an IL-10/STAT3 dependent mechanism: implications for traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 65. 10.1186/s12974-017-0843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi K.; Ohtaki H.; Nakamachi T.; Yofu S.; Satoh K.; Miyamoto K.; Song D.; Tsunawaki S.; Shioda S.; Aruga T. Gp91phox (NOX2) in classically activated microglia exacerbates traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 41. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Ma M. W.; Dhandapani K. M.; Brann D. W. NADPH oxidase 2 deletion enhances neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2018, 123, 62–71. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran R.; Kim T.; Mehta S. L.; Udho E.; Chanana V.; Cengiz P.; Kim H.; Kim C.; Vemuganti R. A combination antioxidant therapy to inhibit NOX2 and activate Nrf2 decreases secondary brain damage and improves functional recovery after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 1818–1827. 10.1177/0271678X17738701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Wang H.; Zhang X. Inhibition of NOX2 contributes to the therapeutic effect of aloin on traumatic brain injury. Folia Neuropathol. 2020, 58, 265–274. 10.5114/fn.2020.100069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry R. J.; Ritzel R. M.; Barrett J. P.; Doran S. J.; Jiao Y.; Leach J. B.; Szeto G. L.; Wu J.; Stoica B. A.; Faden A. I.; Loane D. J. Microglial Depletion with CSF1R Inhibitor During Chronic Phase of Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Reduces Neurodegeneration and Neurological Deficits. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 2960–2974. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2402-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.; Zhao Q.; Liu X.; Yan T. Human umbilical cord blood cells rescued traumatic brain injury-induced cardiac and neurological deficits. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 278. 10.21037/atm.2020.03.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M. W.; Wang J.; Dhandapani K. M.; Wang R.; Brann D. W. NADPH oxidases in traumatic brain injury - Promising therapeutic targets?. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 285–293. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavone S.; Neri M.; Trabace L.; Turillazzi E. The NADPH oxidase NOX2 mediates loss of parvalbumin interneurons in traumatic brain injury: human autoptic immunohistochemical evidence. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8752. 10.1038/s41598-017-09202-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. M.; Chen W.; Liu R. N.; Zhao Y. Notch inhibitor can attenuate apparent diffusion coefficient and improve neurological function through downregulating NOX2-ROS in severe traumatic brain injury. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018, 12, 3847–3854. 10.2147/DDDT.S174037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wang H. Targeting the NF-E2-Related Factor 2 Pathway: a Novel Strategy for Traumatic Brain Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 1773–1785. 10.1007/s12035-017-0456-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W.; Cui G.; Li T.; Chen H.; Zhu J.; Ding Y.; Zhao L. Docosahexaenoic Acid Protects Traumatic Brain Injury by Regulating NOX2 Generation via Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1839–1850. 10.1007/s11064-020-03078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]