Abstract

Gaussia princeps luciferase (GLuc 18.2 kDa; 168 residues) is a marine copepod luciferase that emits a bright blue light when oxidizing coelenterazine (CTZ). GLuc is a small luciferase, attracting much attention as a potential reporter protein. However, compared to firefly and Renilla luciferases, which have been thoroughly characterized and are used in a wide range of applications, structural and biophysical studies of GLuc have been slow to appear. Here, we review the biophysical and mutational studies of GLuc's bioluminescence from a structural viewpoint, particularly in view of its recent NMR solution structure, where two homologous sequential repeats form two anti-parallel bundles, each made of four helices, grabbing a short N-terminal helix. Additionally, a long loop classified as an intrinsically disordered region separates the two bundles forming one side of a hydrophobic pocket that is most likely the binding/catalytic site. We compare the NMR-determined structure with a recent AlphaFold2 prediction. Overall, the AlphaFold2 structure was in line with the solution structure; however, it surprisingly revealed a possible, alternative conformation, where the N-terminal helix is replaced by a newly formed α helix in the C-terminal tail that is unfolded in the NMR structure. In addition, we discuss the results of previous mutational analysis focusing on a putative catalytic core identified by chemical shift perturbation analysis and molecular dynamics simulations performed using both the NMR and the AlphaFold2 structures. In particular, we discuss the role of the possible conformational change and the hydrophobic pocket in GLuc’s activity. Overall, the discussion points toward GLuc’s unexpected and unusual characteristics that appear to be much more flexible than traditional enzymes, resulting in a unique mode of catalysis to achieve CTZ oxidative decarboxylation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12551-022-01025-6.

Keywords: Bioluminescence, Intrinsically disordered region (IDR), Dynamic structure, NMR

Introduction

Luciferase is a generic name for enzymes that emit light by catalyzing substrates referred to as luciferin ((Shimomura 2006), pages xix–xxi). A large variety of luciferases from different biological classification members are not necessarily evolutionary-related. Some luciferases, such as those from fireflies and Renilla, are popular reporter proteins and found a wide range of applications in bio-imaging.

Gaussia luciferase (GLuc) from the marine copepod Gaussia princeps, which dwells in tropical or deep subtropical seas, is small luciferase and is attracting much attention as a potential reporter protein. Like other copepod luciferases, GLuc uses coelenterazine (CTZ) as its substrate (Campbell and Herring 1990). The GLuc gene was cloned in 2002 (Verhaegen and Christopoulos 2002). Copepod luciferases usually have a small molecular weight of about 20 kDa; they have an N-terminal secretory signal of about 20 amino acids and contain two tandem repeats of about 60 amino acids, featuring highly conserved cysteine residues (also Arg and Pro just before the fifth cysteine in each repeat) (Takenaka et al. 2013) (Fig. 1).

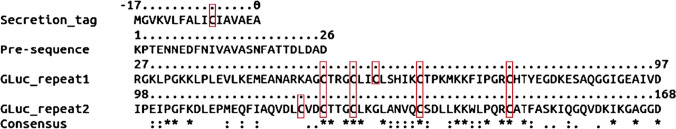

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence of GLuc (Q9BLZ2). Residues − 17–0 are the secretion peptide. The two tandem are located in sequences 27–97 and 98–168. The two repeat sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL Omega (ver. 1.2.4) (Sievers et al. 2011) Identical residues are marked “*”, the highly similar ones are marked “:”, the poorly similar ones are marked “.”, and the cysteines are red squared. The relative positions of the cysteines in each tandem repeat are fully conserved except for C59 and C120

However, GLuc’s biophysical characterization has been slow to appear, possibly because of the lack of an efficient E. coli expression system, which is the most common and low-cost bacterial expression system. Indeed, GLuc contains 10 cysteines, and the active, natively folded GLuc contains five disulfide bonds, making its refolding procedure challenging (Rathnayaka et al. 2010; Dijkema et al. 2021). The presence of five disulfide bonds hampers expression in E. coli using standard protocols by producing aberrant SS bonds resulting in the expression of missfolded proteins in the inclusion body of E. coli (Wu et al. 2015). Methods such as fusion with pelB leader sequence (Maguire et al. 2009; Tannous 2009), cell-free systems (Goerke et al. 2008), and low-temperature expression (Rathnayaka et al. 2010) were reported, but the yield of natively folded GLuc remained insufficient for high-resolution structural studies.

The attachment of a solubility enhancement peptide tag (SEP-tag) containing nine aspartic acids to GLuc’s C-terminus yielded a sufficient amount of proteins for biophysical studies. The SEP tag increases the yield of natively folded multi-SS bond proteins by improving the solubility of the protein and thus enabling time for spontaneous refolding and formation of native SS bonds before the protein aggregates. Eventually, the SEP-tag increased the final yield of soluble and functional GLuc to nearly 1 mg from 200 mL of E. coli cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) (Rathnayaka et al. 2011) and 1.5 mg from 1 L M9 minimal media enabling high-resolution NMR studies with 15 N and 13C labeled GLuc (Rathnayaka et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2015).

Structures of GLuc

GLuc is an all-α-helix protein made of nine helices as determined by heteronuclear multidimensional NMR (Wu et al. 2020). The 1H-15 N HSQC spectrum exhibited dispersed and sharp peaks, indicating a stable and well-folded monomeric structure. Broadened signals suggested that the region encompassing the C136/C148 SS bond is flexible. The superimposition of nineteen NMR-derived structures with the lowest overall energy shows that GLuc has nine helices (α1–α9, Fig. 1). The N- (residues 1–9) and C-terminus (residues 146–168) of GLuc are highly disordered (Fig. 2a). In addition, residues 19–34 and 82–96 are highly mobile and can be considered as intrinsically disordered regions (IDR). GLuc’s core structure is thus formed by residues 10–145, where residues10–18, 35–81, and 97–145 are well-defined with an average backbone RMSD of 1.39 Å ± 0.39 Å (Table 1 and Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

NMR-derived structure of GLuc (PDB:7D2O). a The superimposition of 19 structures with the least violations is shown. b The ribbon model is shown with the flexible N- and C-terminus in blue, two IDR (as defined by superimposition and 1H-.15N HSQC) (Wu et al. 2020) in cyan, five disulfide bonds in yellow, and the central cavity in transparent light blue. (c) Schematic representation of GLuc’s fold. The helices in tandem repeats 1 and 2 are shown in yellow and green, respectively. This fold looks similar to an EF-hand fold but the arrangement of the helices actually is a mirror image. Also, there are SS-bonds instead of beta-strands in the EF-hand fold. This is a novel fold according to a DALI (Hasegawa and Holm 2009) search of the PDB (as of 2021)

Table 1.

Several types of dynamics revealed by NMR

| Structured | Unstructured | |

|---|---|---|

| Rigid1 | α3, α4, α5, α7, α8, α9 | - |

| Slow motion (~ ms) 2 | α1 | Loop between α5 and α6, loop after α9 |

| Fast motion (< ns)3 | α2 | N- and C-termini |

1Stable regions as observed by H/D exchange. 2Slow (~ ms) dynamics are observed by relaxation dispersion. 3Very fast (< 1 ns) dynamics were observed by heteronuclear NOE.

The structure of GLuc is novel, and the two homologous sequential repeats form two anti-parallel bundles, each made of four helices, grabbing a short N-terminal helix. This structure is different from the structures of Renilla luciferase (RLuc) (Loening et al. 2007), Oplophorus luciferase (OLuc) (Tomabechi et al. 2016), and apo-aequorin (Head et al. 2000), which, like GLuc, use CTZ as a substrate and are ATP-independent luciferases. In addition, a surface-accessible hydrophobic cavity made of 19 residues (N10, V12, A13, V14, S16, N17, F18, L60, S61, I63, K64, C65, R76, C77, H78, T79, F113, I114, V117) was observed in the NMR structure, suggesting a binding/activity site for CTZ (Fig. 2b).

Finally, based on the experimental observation that the two isolated domains exhibit bioluminescence (Inouye and Sahara 2008), we speculated that the repeats would form independent domains that can fold in isolation (Wu et al. 2016). However, it turned out GLuc folds in a single domain structure (Wu et al. 2020), opening a new question: How can a single isolated tandem exhibit activity since they are probably not natively folded? Answering this question is worth further studies, especially in light of the complementary fragment strategy for using GLuc as a reported protein (Remy and Michnick 2006).

Recently, the GLuc structure was used as a target for CASP14 structure prediction contest. GLuc’s AlphaFold2 predicted structure (AF2 structure) was assessed and compared to the NMR-derived one (Huang et al. 2021). AF2 prediction indicated a well-defined structure for residues 36–75 and 96–164, largely agreeing with the well-defined regions in the NMR-derived structure: 10–18, 36–81, and 96–145 (Fig. 3a). The non-agreeing regions were thus 10–18 and 146–164. The significant difference between the NMR and AF2 structures is the packing of the central helix wrapped by the two helical bundles formed by the homologous sequence repeats (Fig. 3b). Namely, the central helix is formed by the N-terminal helix α1 in the NMR structure, but in AF2, the N-terminal helix α1 is replaced by a newly formed C-terminal helix in a segment that is unfolded according to the NMR structure. These helix-core packing interactions are mutually exclusive, but the two forms could exist in dynamic equilibrium. This hypothesis is supported by the relaxation dispersion NMR experiment indicating slow conformational dynamics around helix α1 and the loop after α9 (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Ribbon model of the AlphaFold2 (AF2) predicted structure. a In the ribbon model of AF2 structure, disulfide bonds are colored yellow, and the central cavity is shown in transparent light blue. b The superimposing of AF2 structure (blue) and NMR-derived structure (white, PDB:7D2O). The two structures overlap very well except for the N-terminal helix in the NMR structure and the newly formed C-terminal in the predicted AF2 structure. The second IDR (residues 82–96) in both structures, the flexible C-terminus (residues 146–168) in the NMR structure, and the N-terminus (residues 1–34) in the AF2 structure are not shown

Structural view of mutational studies

There have been a few studies for improving and modifying the GLuc’s bioluminescence activity based on random or educated guesses (Kim et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2016). Revisiting the results of mutational analysis based on the recent GLuc structure might shed light on the mechanism of GLuc’s bioluminescence.

Previous mutational analysis indicates that F72, I73, R76, H78, and Y80 (Kim et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2015) and F113, I114, W143, L144, and F151 (Wu et al. 2016) are activity-related residues. F72, I73, R76, and F151 were identified by NMR, strongly suggesting that these four residues are directly involved in the binding of CTZ (Takatsu et al. 2022). No chemical shift perturbation was observed for H78, Y80, F113, and I114, which are located at or near the hydrophobic cavity. We thus speculate that these residues affect the Gluc's activity by changing the property of the cavity without directly binding to CTZ. Finally, the role of W143 and L144 (Wu et al. 2016) which are located in the unstructured C-terminus in the NMR structure, is difficult to rationalize. On the other hand, the AF2 model could explain the involvement of W143 and L144. Namely, W143 and L144 are included in the cavity wall of the predicted structure (Huang et al. 2021), and W143 and L144 would participate in the hydrophobic cavity.

Additionally, titration with salt or aza-CTZ to the NMR sample did not indicate the conformational change predicted by AF2 (Takatsu et al. 2022), but the intensities of several peaks were reduced upon the addition of salt or aza-CTZ (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Attenuated HSQC peaks. a Peak intensities reduced by 40% upon the addition of Aza-CTZ (top) and 50% upon the addition of NaCl (bottom) are shown by arrows (red, backbone NH; cyan, Arg epsilon NH; purple, Arg epsilon NH and backbone NH). b The ribbon model shows peaks with decreased intensities in yellow. The green residues are histidines as they might be involved in oxidation, and the central cavity is shown in transparent gray blue

Computational analysis of GLuc's conformation change and its binding mode to CTZ

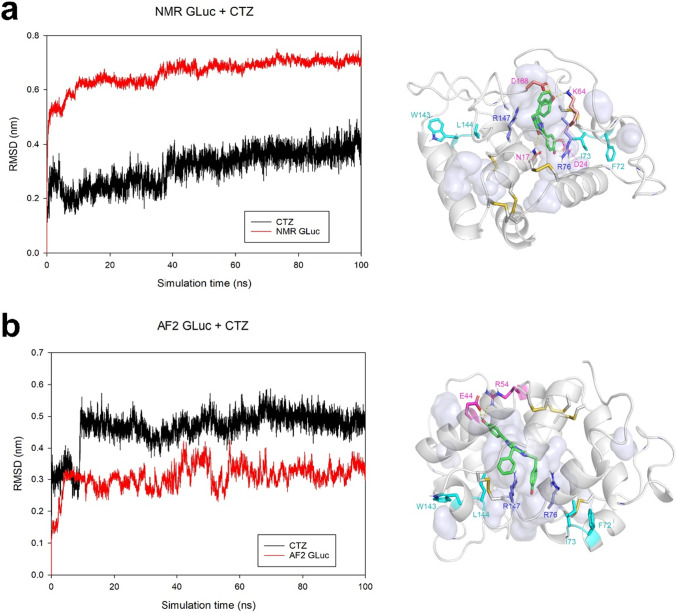

Finally, let us discuss some preliminary computational analyses that may further shed light on the predicted structural change and the mode of GLuc’s binding with CTZ (Fig S1). The NMR-derived structure and AF2 structure were respectively docked with a CTZ, followed by a 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation in a charge-neutralized water box (T = 300 k and P = 1 bar). In both the NMR-derived structure and the AF2 structure, the CTZ positionstabilized after 80 ns (Fig. 5, left panels). We, therefore, calculated the CTZ binding energy using the trajectory between 80 and 100 ns using g_mmpbsa (Kumari et al. 2014). The binding energy of CTZ with the NMR-derived structure (− 249.7 + / − 3.7 kJ/mol) was higher than that calculated with the AF2 structure (− 131.8 + / − 4.8 kJ/mol). This was rationalized by (1) the number of hydrogen bonds between the C-2, C-6 groups and the keto oxygen on the central pyridine imidazole ring of CTZ (the AF2 structure merely bonded with the C-6 group of CTZ) and (2) the narrower hydrophobic cavity favoring interactions with the low-solubility CTZ (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the catalytic mechanism of Obelin (an EF-hand photoprotein that uses CTZ) indicated that positively charged residues located nearby the keto oxygen on the central pyridine imidazole ring of CTZ and play a role in CTZ oxidation (Chen et al. 2021). R76 and R147 are speculated as two catalyze-related residues because they are near and symmetry to the CTZ as center both in the NMR-derived structure and AF2 structure, and R76 has been experimental demonstrated essential for activity (Kim et al. 2011). The mutagenesis on surrounding residues should further suggest the significance of R76 and R147, as F72/I73 and W143/L144, respectively, support R76 and R147 and shield them from solvent; the mutagenesis of these four residues altered the intensity and wavelength of bioluminescence (Kim et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2016) (Fig. 5, right panels).

Fig. 5.

MD simulation of the docked complex between CTZ and NMR determined GLuc structure (a) or AF2 predicted GLuc structure (b). A CTZ was docked in GLuc using AutoDock Vina (Ver 1.1.2) (Trott and Olson 2010), and the docked complex was solved in a cubic box filled with water models using GROMACS (Ver 2021.2) (Van Der Spoel et al. 2005). Na+ and Cl− were used to neutralize the system, which was followed by energy minimization, NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature), and NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) equilibration. The temperature and pressure of the system were stabilized at 300 K and 1 bar, respectively. A 100 ns simulation with a time step of 2 fs was performed. The red and black lines in the left panel represent the RMSDs of GLuc and CTZ (GLuc is superimposed) in the GLuc-CTZ docked complex. Conformations generated during the 100 ns simulation were clustered (RMSD < 0.2 nm) and the central conformation in the largest cluster was selected as the representative structure (right panel). Residues forming hydrogen bonds with CTZ are in magentas; F72, I73, W143, and L144 were colored in cyan; R76 and R147 are colored in blue; the disulfide bonds are in yellow; and the cavity is shown in transparent gray blue

As a matter of fact, the actual binding mode of CTZ remains a matter of some debate. Our above discussion, mainly based on GLuc’s structure, suggests that one CTZ molecule binds to GLuc. For example, our docking simulation identified one binding site (we did not search for a second one, but all docked complexes generated by AutoDock only identified one binding cavity, either for the NMR-derived structure or for the AF2 structure). However, a titration study showing positive cooperativity with a Hill coefficient of 1.8 suggests two interacting binding sites (Tzertzinis et al. 2012; Larionova et al. 2018). Our AutoDock simulation shows that CTZ remains in the cavity of boththe NMR and the AF2 structure., We may thus speculate that the reported cooperativity is the result of the aforementioned conformational change between the NMR and the AF2 structures rather than the presence of two catalytic sites, as seen in traditional models.

Conclusion

We have reviewed how the recent determination of GLuc structure has advanced our understanding of the mode of function of GLuc. However, new questions have appeared and could be worth further studies. In particular, the binding mode of CTZ is not fully clarified. Another question is how an isolated domain can exhibit partial activity even though it is most probably unfolded or only partially folded. Finally, the role of the N-terminal helix unfolds and whether is it replaced by the newly formed C-terminal helix upon binding with CTZ remains to be fully understood. We reported some preliminary computational analysis, but future simulation studies coupled with structure-based designed mutants (such as deletion mutants lacking α1 or the C-termini region) will hopefully answer these questions, revealing the full scope of this unique and very special enzyme.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

NW performed computational analysis. NW, NK, YK, and TY wrote the review and agree to publish it.

Funding

This study was supported by a JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI-18H02385) to YK and Henan Provincial Key Scientific Research Project Plan for Colleges and Universities to NW (Grant No. 23A180002).

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nan Wu and Naohiro Kobayashi share equal contribution.

Contributor Information

Yutaka Kuroda, Email: ykuroda@cc.tuat.ac.jp.

Toshio Yamazaki, Email: toshio.yamazaki@riken.jp.

References

- Campbell A, Herring P. Imidazolopyrazine bioluminescence in copepods and other marine organisms. Mar Biol. 1990;104:219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF01313261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Vysotski E, Liu Y. H2O-bridged proton-transfer channel in emitter species formation in obelin bioluminescence. J Phy Chem B. 2021;125(37):10452–10458. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c03985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutant EP, Goyard S, Hervin V, Gagnot G, Baatallah R, Jacob Y, Rose T, Janin YL. Gram-scale synthesis of luciferins derived from coelenterazine and original insights into their bioluminescence properties. Org Biomol Chem. 2019;17(15):3709–3713. doi: 10.1039/C9OB00459A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkema FM, Nordentoft MK, Didriksen AK, Corneliussen AS, Willemoës M, Winther JR. (2021) Flash properties of Gaussia luciferase are the result of covalent inhibition after a limited number of cycles. Protein Sci 30(3):638–649. 10.1002/pro.4023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goerke AR, Loening AM, Gambhir SS, Swartz JR. Cell-free metabolic engineering promotes high-level production of bioactive Gaussia princeps luciferase. Metab Eng. 2008;10(3–4):187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Holm L. Advances and pitfalls of protein structural alignment. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(3):341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head JF, Inouye S, Teranishi K, Shimomura O. The crystal structure of the photoprotein aequorin at 2.3 a resolution. Nature. 2000;405(6784):372–376. doi: 10.1038/35012659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YJ, Zhang N, Bersch B, Fidelis K, Inouye M, Ishida Y, Kryshtafovych A, Kobayashi N, Kuroda Y, Liu G, LiWang A, Swapna GVT, Wu N, Yamazaki T, Montelione GT. Assessment of prediction methods for protein structures determined by NMR in casp14: Impact of alphafold2. Proteins. 2021;89(12):1959–1976. doi: 10.1002/prot.26246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S, Sahara Y. Identification of two catalytic domains in a luciferase secreted by the copepod Gaussia princeps. Biochem Biophys Res Co. 2008;365(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SB, Suzuki H, Sato M, Tao H. Superluminescent variants of marine luciferases for bioassays. Anal Chem. 2011;83(22):8732–8740. doi: 10.1021/ac2021882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R, Kumar R, Lynn A. G_mmpbsa—a gromacs tool for high-throughput mm-pbsa calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54(7):1951–1962. doi: 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larionova MD, Markova SV, Vysotski ES. Bioluminescent and structural features of native folded Gaussia luciferase. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;183:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loening AM, Fenn TD, Gambhir SS. Crystal structures of the luciferase and green fluorescent protein from Renilla reniformis. J Mol Biol. 2007;374(4):1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire CA, Deliolanis NC, Pike L, Niers JM, Tjon-Kon-Fat LA, Sena-Esteves M, Tannous BA. Gaussia luciferase variant for high-throughput functional screening applications. Anal Chem. 2009;81(16):7102–7106. doi: 10.1021/ac901234r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka T, Tawa M, Sohya S, Yohda M. Biophysical characterization of highly active recombinant Gaussia luciferase expressed in Escherichia coli. BBA Proteins and Proteomics. 2010;9:1902–1907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathnayaka T, Tawa M, Nakamura T, Sohya S, Kuwajima K, Yohda M. Solubilization and folding of a fully active recombinant Gaussia luciferase with native disulfide bonds by using a SEP-tag. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1814;12:1775–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy I, Michnick SW. A highly sensitive protein-protein interaction assay based on Gaussia luciferase. Nat Methods. 2006;3(12):977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura O. Bioluminescence: Chemical principles and methods. Singapore: World Scientific; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, Mcwilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using clustal omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7(1):539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takatsu K, Kobayashi N, Wu N, Janin YL, Yamazaki T, and Kuroda Y, (2022) Biophysical analysis of Gaussia luciferase bioluminescence mechanisms using a non-oxidizable coelenterazine. BBA Proteins and Proteomics. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Takenaka Y, Noda-Ogura A, Imanishi T, Yamaguchi A, Gojobori T, Shigeri Y. Computational analysis and functional expression of ancestral copepod luciferase. Gene. 2013;528(2):201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannous BA. Gaussia luciferase reporter assay for monitoring biological processes in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(4):582–591. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomabechi Y, Hosoya T, Ehara H, Sekine S, Shirouzu M, Inouye S. Crystal structure of nanokaz: the mutated 19 kDa component of oplophorus luciferase catalyzing the bioluminescent reaction with coelenterazine. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2016;470(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.12.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. Autodock vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzertzinis G, Schildkraut E, Schildkraut I. Substrate cooperativity in marine luciferases. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e40099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJ. Gromacs: Fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaegen M, Christopoulos TK. Bacterial expression of in vivo-biotinylated aequorin for direct application to bioluminometric hybridization assays. Anal Biochem. 2002;306(2):314–322. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Rathnayaka T. Kuroda Y, Bacterial expression and re-engineering of Gaussia princeps luciferase and its use as a reporter protein. BBA-Proteins Proteomics. 2015;10:1392–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Kamioka T, Kuroda Y. A novel screening system based on VanX-mediated autolysis—application to Gaussia luciferase. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113(7):1413–1420. doi: 10.1002/bit.25910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Kobayashi N, Tsuda K, Unzai S, Saotome T, Kuroda Y, Yamazaki T. Solution structure of Gaussia luciferase with five disulfide bonds and identification of a putative coelenterazine binding cavity by heteronuclear NMR. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.