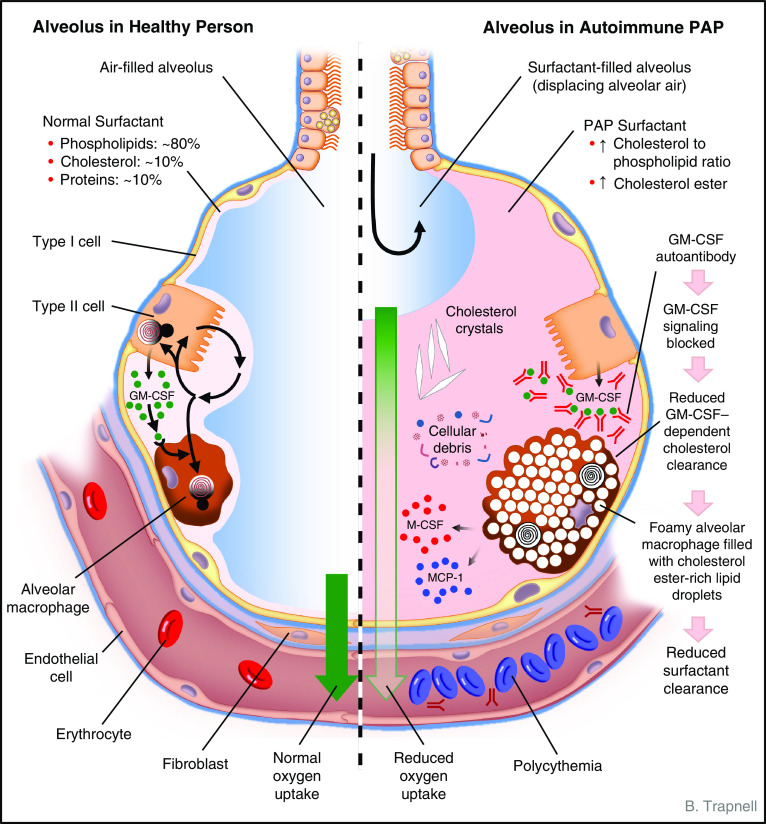

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting the anatomy and biology of the alveolus in health (left) and autoimmune pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) (right). Normally, alveolar structure and function are maintained by a surfactant layer sufficiently thick (about one to three molecules) to reduce surface tension and thin enough to permit adequate diffusion of oxygen across the alveolar wall. Homeostasis is maintained by balanced secretion of surfactant by alveolar type II cells and clearance by type II cells and by alveolar macrophages, which require GM-CSF (granulocyte/macrophage colony–stimulating factor) to export cholesterol normally. In autoimmune PAP, autoantibodies bind and block GM-CSF from activating receptors on alveolar macrophages (and other cells, e.g., neutrophils). Because surfactant uptake by alveolar macrophages is GM-CSF independent and export of surfactant-derived cholesterol is GM-CSF dependent, cholesterol accumulates within the cytoplasm. Alveolar macrophages esterify and sequester cholesterol within intracytoplasmic vesicles (as a cell-protective mechanism), resulting in foamy-appearing cells with secondary impairment of multiple macrophage functions, including phagocytosis and surfactant clearance. Over time, alveoli fill with insoluble surfactant sediment, cellular debris, cholesterol crystals, and several cytokines (indicated; see text). A thickened surfactant layer and surfactant-filled alveoli contribute to reduced oxygen delivery, resulting in hypoxemia, dyspnea, and in severe cases polycythemia, respiratory failure, and death. Pulmonary fibrosis (not shown) also occurs in some patients. See text for further details. MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; M-CSF = macrophage colony–stimulating factor.