Abstract

Objectives

To describe the in vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam against non-Morganellaceae Enterobacterales (NME) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa recently isolated from lower respiratory tract infection samples by hospital laboratories in Western Europe.

Methods

From 2018 to 2020, 29 hospital laboratories in six countries in Western Europe participated in the SMART global surveillance programme and contributed 4414 NME and 1995 P. aeruginosa isolates. MICs were determined using the CLSI broth microdilution method and interpreted by EUCAST (2021) breakpoints. β-Lactamase genes were identified in selected isolate subsets (2018–20) and oprD sequenced in molecularly characterized P. aeruginosa (2020).

Results

Imipenem/relebactam (99.1% susceptible), amikacin (97.2%), meropenem (96.1%) and imipenem (95.9%) were the most active agents tested against NME; by country, relebactam increased imipenem susceptibility from <1% (France, Germany, UK) to 11.0% (Italy). A total of 96.0% of piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant (n = 990) and 81.1% of meropenem-resistant (n = 106) NME were imipenem/relebactam-susceptible. Only 0.5% of NME were MBL positive, 0.9% were OXA-48-like-positive (MBL negative) and 2.8% were KPC positive (MBL negative). Amikacin (91.5% susceptible) and imipenem/relebactam (91.4%) were the most active agents against P. aeruginosa; 72.3% of isolates were imipenem-susceptible. Relebactam increased susceptibility to imipenem by 34.4% (range by country, 39.1%–73.5%) in piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant and by 37.4% (3.1%–40.5%) in meropenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. Only 1.8% of P. aeruginosa isolates were MBL positive. Among molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates from 2020, 90.9% (30/33) were oprD deficient.

Conclusions

Imipenem/relebactam appears to be a potential treatment option for lower respiratory tract infections caused by piperacillin/tazobactam- and meropenem-resistant NME and P. aeruginosa in Western Europe.

Introduction

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) remain important causes of morbidity and mortality.1,2 HAP is the second most common hospital-acquired infection.1 Most cases of HAP arise in non-ventilated patients; however, the highest risk for HAP is in patients following endotracheal intubation and in those receiving mechanical ventilation.1 Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are common pathogens in HAP and VAP.1,2

In February 2020, the EMA approved imipenem/relebactam for: the treatment of HAP, including VAP, in adults; the treatment of bacteraemia that occurs in association with, or is suspected to be associated with HAP or VAP, in adults; and the treatment of infections due to aerobic Gram-negative organisms in adults with limited treatment options.3 Imipenem/relebactam combines the carbapenem imipenem with the non-β-lactam diazabicyclooctane (DBO) inhibitor relebactam, and restores activity to imipenem in most isolates of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa that carry Ambler class A (ESBLs, KPCs) and class C (AmpC) β-lactamases as well as carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa resulting from porin loss or efflux combined with Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinase (PDC) overexpression.4,5

The objectives of the current study were to determine the in vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam against lower respiratory tract isolates of non-Morganellaceae Enterobacterales (NME) and P. aeruginosa collected from patients attending hospitals in Western Europe, including piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant and carbapenem-resistant isolates, and to identify β-lactamases among resistant isolate subsets.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

From 2018 to 2020, 29 hospital laboratory sites in six countries in Western Europe participated in the SMART global surveillance programme (France, 4 sites; Germany, 6 sites; Italy, 5 sites; Portugal, 3 sites; Spain, 6 sites; UK, 5 sites). Each site was asked to collect 100 consecutive, clinically significant isolates of aerobic or facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli from lower respiratory tract infection (RTI) samples per year and to transport them to a central laboratory (IHMA, Monthey, Switzerland or Schaumburg, IL, USA), where organism identity was confirmed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) and antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the CLSI reference broth microdilution method.6 Isolates were restricted to one isolate per patient per year. Species-specific quotas are not used in the collection of isolates by the SMART global surveillance programme. Species in the genera Proteus, Providencia and Morganella (Morganellaceae) frequently demonstrate elevated MICs of imipenem (and imipenem/relebactam) by mechanisms other than by carbapenemases7 and were excluded from the analyses for Enterobacterales isolates. A total of 4414 NME isolates [91.7% of all (n = 4811) Enterobacterales isolates collected] and 1995 P. aeruginosa isolates were received by the SMART global surveillance programme from the 29 hospital laboratory sites from 2018 to 2020. Carbapenem resistance was defined using meropenem (i.e. meropenem-resistant). Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online) summarizes the species distribution among all, piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant, and meropenem-resistant NME isolates tested. MICs were interpreted using 2021 EUCAST v11 breakpoints.8

Screening for β-lactamase genes

Isolates meeting the following phenotypic criteria were screened for β-lactamase genes: NME isolates (excluding Serratia spp.) testing with imipenem or imipenem/relebactam MIC values of ≥2 mg/L and P. aeruginosa isolates testing with imipenem or imipenem/relebactam MIC values of ≥4 mg/L collected during 2018–20; isolates of NME and Serratia spp. testing with ertapenem MIC values of ≥1 mg/L collected in 2018 only; isolates of Serratia spp. testing with imipenem MIC values of ≥4 mg/L collected in 2018 only; and Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa isolates testing with ceftolozane/tazobactam MIC values of ≥4 and ≥8 mg/L, respectively, collected during 2018–20. Published multiplex PCR assays were used to screen for the following β-lactamase genes: ESBLs (CTX-M, GES, PER, SHV, TEM, VEB); acquired AmpC β-lactamases (ACC, ACT, CMY, DHA, FOX, MIR, MOX) and the chromosomal AmpC intrinsic to P. aeruginosa (PDC); serine carbapenemases [GES, KPC, OXA-48-like (Enterobacterales), OXA-24-like (P. aeruginosa)]; and MBLs (GIM, IMP, NDM, SPM, VIM).9,10 All detected genes encoding carbapenemases, ESBLs and PDC were amplified using gene-flanking primers and sequenced (Sanger). For P. aeruginosa collected in 2020 only, isolates with ceftolozane/tazobactam MIC values ≥8 mg/L, imipenem MIC values ≥4 mg/L and imipenem/relebactam MIC values ≥4 mg/L were characterized by short-read WGS (Illumina HiSeq 2 × 150 bp reads) to a targeted coverage depth of 100×11 and analysed using the CLC Genomics Workbench (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD, USA). The ResFinder database was used to detect β-lactamase genes.12 The oprD gene from each assembly was queried for deficiency by pairwise alignment to a reference sequence from P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (accession: NC_002516, locus tag: PA0958). For the purpose of this study, a deficiency was defined as any frameshift mutation, nonsense mutation, ablation of the reference start or stop codons without a replacement immediately adjacent, or an in-frame insertion or deletion of at least 20 codons. A total of 86 NME and 110 P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2018 (1.9% of 4414 NME and 5.5% of 1995 P. aeruginosa isolates) were not available for molecular characterization and were not included in the denominators used for carbapenemase rate calculations. This included 55 NME and 22 P. aeruginosa isolates collected in Portugal, all 31 NME and all 51 P. aeruginosa isolates collected at one site in the UK in 2018, and all 37 P. aeruginosa isolates collected at one site in Spain. In addition, 72 randomly selected P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2020 that met the testing criteria were also not molecularly characterized (30.8% of 234 P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2020 that qualified for molecular characterization). For each country, the percentage of qualified isolates collected in 2020 that were not characterized was considered when calculating carbapenemase rates.

Results

The most active antimicrobial agents tested against all NME isolates were imipenem/relebactam (99.1% susceptible), amikacin (97.2%), meropenem (96.1%) and imipenem (95.9%); percent susceptible values were >17% lower for cefepime (81.6% susceptible), levofloxacin (79.8%), piperacillin/tazobactam (77.6%) and ceftazidime (75.0%) than for imipenem/relebactam (Table 1). Greater than 98% of NME isolates from participating hospital laboratory sites in all six Western European countries were imipenem/relebactam susceptible. Overall, relebactam increased the susceptibility of NME isolates to imipenem by 3.2% (compared with imipenem alone) with increases ranging from 11.0% in Italy to increases of <1% in France, Germany and the UK.

Table 1.

In vitro susceptibility of all isolates of NME and isolates with β-lactam-resistant phenotypes collected by the SMART global surveillance programme from 2018 to 2020 in Western Europe

| Percentage of isolates susceptible (number of susceptible isolates in TZP- and MEM-resistant isolate subsets) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype/country/region (n) | IMR | IMP | MEM | FEP | CAZ | TZP | LVX | AMK |

| All isolates | ||||||||

| France (612) | 99.8 | 99.8 | 99.8 | 84.2 | 74.2 | 76.8 | 86.0 | 98.0 |

| Germany (1020) | 99.2 | 98.8 | 99.3 | 89.8 | 82.1 | 83.3 | 90.7 | 99.3 |

| Italy (715) | 98.7 | 87.7 | 87.8 | 70.8 | 65.6 | 71.2 | 69.7 | 90.9 |

| Portugal (482) | 99.4 | 92.5 | 92.1 | 65.4 | 56.2 | 60.0 | 68.3 | 97.5 |

| Spain (1021) | 98.1 | 96.0 | 96.7 | 83.5 | 79.4 | 80.9 | 74.3 | 97.6 |

| UK (564) | 99.8 | 99.1 | 99.3 | 88.1 | 83.3 | 85.1 | 85.6 | 99.7 |

| Western Europe (4414) | 99.1 | 95.9 | 96.1 | 81.6 | 75.0 | 77.6 | 79.8 | 97.2 |

| TZP-resistant isolates | ||||||||

| France (142) | 99.3 (141) | 99.3 (141) | 99.3 (141) | 57.0 (81) | 31.0 (44) | 0 (0) | 67.6 (96) | 94.4 (134) |

| Germany (170) | 95.9 (163) | 94.1 (160) | 95.9 (163) | 72.4 (123) | 38.2 (65) | 0 (0) | 78.8 (134) | 96.5 (164) |

| Italy (206) | 95.6 (197) | 57.8 (119) | 57.8 (119) | 27.2 (56) | 17.0 (35) | 0 (0) | 30.1 (62) | 72.3 (149) |

| Portugal (193) | 98.5 (190) | 81.4 (157) | 80.3 (155) | 32.1 (62) | 13.5 (26) | 0 (0) | 39.4 (76) | 94.8 (183) |

| Spain (195) | 90.3 (176) | 79.0 (154) | 82.6 (161) | 46.2 (90) | 28.2 (55) | 0 (0) | 39.0 (76) | 90.8 (177) |

| UK (84) | 98.8 (83) | 94.1 (79) | 95.2 (80) | 63.1 (53) | 39.3 (33) | 0 (0) | 71.4 (60) | 98.8 (83) |

| Western Europe (990) | 96.0 (950) | 81.8 (810) | 82.7 (819) | 47.0 (465) | 26.1 (258) | 0 (0) | 50.9 (504) | 89.9 (890) |

| MEM-resistant isolatesa | ||||||||

| Italy (64) | 92.2 (59) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.6 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 34.4 (22) |

| Portugal (21) | 95.2 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9.5 (2) | 85.7 (18) |

| Western Europe (106) | 81.1 (86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.9 (2) | 49.1 (52) |

IMR, imipenem/relebactam; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; FEP, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; LVX, levofloxacin; AMK, amikacin.

Only countries with at least 20 meropenem-resistant isolates are shown (not shown: France, n = 0; Germany, n = 5; Spain, n = 15; UK, n = 1).

Against the subset of piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant NME isolates (n = 990), the percent susceptible value for imipenem/relebactam was 96.0% overall, ranging from 99.3% susceptible for isolates from France to 90.3% susceptible for isolates from Spain; 81.8% of isolates were susceptible to imipenem (percent susceptible range by country, 99.3%–57.8%) and 82.7% of isolates were susceptible to meropenem (99.3%–57.8%) (Table 1). Relebactam increased the percent susceptible value to imipenem against piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant NME by as much as 37.9% in isolates from Italy, while for isolates from France the percent susceptible values for imipenem/relebactam and imipenem were identical (99.3%).

Against the subset of meropenem-resistant NME isolates (n = 106), the percent susceptible value for imipenem/relebactam was 81.1% (Table 1). Most meropenem-resistant NME isolates (80.2%; 85/106) were from only two countries (Italy, 92.2% imipenem/relebactam susceptible; Portugal, 95.2%). Very low numbers of meropenem-resistant isolates (<1.5% of isolates) were identified in the remaining countries: France (n = 0); Germany (n = 5); Spain (n = 15); and the UK (n = 1).

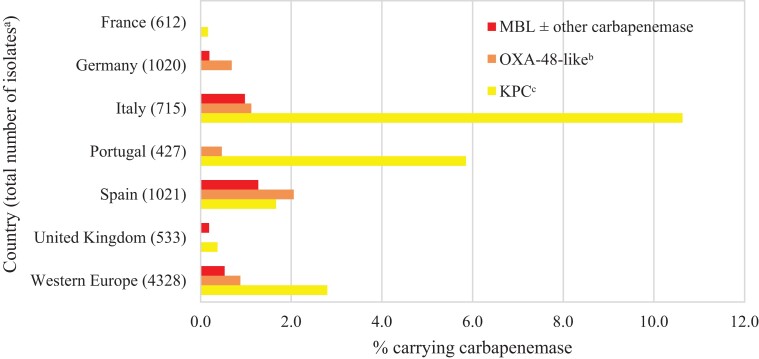

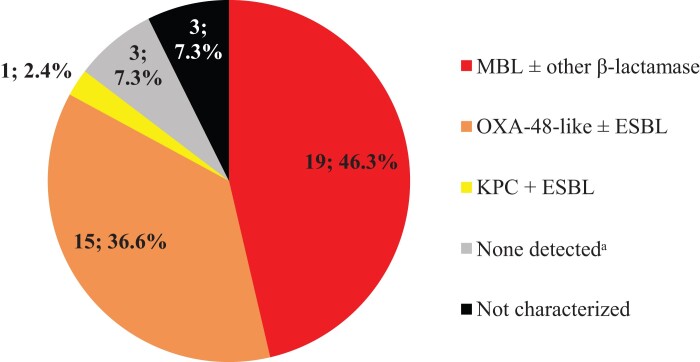

Overall, an estimated 0.5% of all NME isolates from Western Europe carried an MBL, 0.9% carried an OXA-48-like carbapenemase (without a co-carried MBL) and 2.8% carried a KPC (without other co-carried carbapenemases) (Figure 1). MBL and OXA-48-like carbapenemase carriage rates were highest in isolates from Spain (1.3% and 2.1%) and Italy (1.0% and 1.1%). KPC carriage rates were highest in Italy (10.6%) and Portugal (5.9%). MBLs were not identified in isolates from France and Portugal, OXA-48-like carbapenemases were not identified in isolates from France and the UK, and KPCs were not identified in isolates from Germany. MBLs were identified in 50.0% (19/38) and OXA-48-like enzymes (without co-carried MBL) in 39.5% (15/38) of molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant NME isolates; acquired β-lactamases were not identified in only 7.9% (3/38) of molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Estimated carbapenemase rates among NME isolates by country. aExcludes 86 isolates collected in 2018 in Portugal (n = 55) and the UK (n = 31) that were not available for molecular characterization. bExcludes isolates co-carrying MBL; includes one isolate carrying KPC. cExcludes isolates co-carrying MBL and OXA-48-like.

Figure 2.

β-Lactamase gene carriage (n; %) among imipenem/relebactam-resistant NME isolates (n = 41 of 4414 collected isolates; 0.9%). Original-spectrum β-lactamases (e.g. TEM-1) and intrinsic AmpC common to most NME species are not shown. aNo acquired β-lactamases detected.

Among molecularly characterized piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant NME isolates, 43% carried a carbapenemase (29% KPC, 9% OXA-48-like and 5% MBL) and 15% were ESBL positive and/or AmpC positive (no carbapenemase); acquired β-lactamase genes were not identified in 42% of isolates (Figure S1). Marked variation was observed across countries in the percentages of molecularly characterized piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant NME isolates with serine carbapenemases or MBLs (2.3% in France to 74.0% in Italy), with only ESBLs and/or AmpCs (4.3% in the UK to 34.7% in Portugal), and without β-lactamase genes identified (range 12.2% in Italy to 82.6% in the UK). In comparison, almost every molecularly characterized meropenem-resistant NME isolate was carbapenemase positive (>99%; 100/101) with 83% of carbapenemase-positive isolates carrying KPC (Figure S2).

For all isolates from Western Europe, imipenem/relebactam was equally active (99% susceptible) against ICU and non-ICU isolates of NME (Table S2). Percent susceptible values for all other agents were lower than for imipenem/relebactam and, unexpectedly, higher in isolates from ICU than non-ICU patients, with differences of >5% observed for levofloxacin (10.2%) and cefepime (6.6%). Imipenem/relebactam was also equally active (99% susceptible or higher) against isolates collected from patients hospitalized for <48 and ≥48 h at the time of specimen collection. Overall, percent susceptible values for all other agents tested were higher in Western Europe isolates from patients hospitalized <48 h at the time of specimen collection, with differences of >5% observed for ceftazidime (10.5%), piperacillin/tazobactam (10.2%) and cefepime (7.5%). Some individual country-to-country variation was observed in percent susceptible values for NME isolates for both ward type and length of stay at the time of specimen collection parameters. For instance, for the carbapenems, the difference between ward types was due primarily to isolates from Italy showing a >10% lower percent susceptible value in non-ICU than ICU isolates. Isolates from all other countries showed similar carbapenem-susceptible rates in ICU and non-ICU isolates or isolates from ICUs were slightly less susceptible.

The most active agents against all isolates of P. aeruginosa were amikacin (91.5% susceptible) and imipenem/relebactam (91.4%); all other agents had a percent susceptible value of approximately 80% or less. (Table 2). The imipenem/relebactam percent susceptible values were 73.5% for piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant and 40.5% for meropenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. The imipenem/relebactam percent susceptible value was highest in isolates from Germany (96.8%) and France (96.1%); isolates from patients in all six countries were ≥88% susceptible. Overall, relebactam increased the susceptibility to imipenem of all isolates of P. aeruginosa by 19.1% compared with imipenem alone (increases ranged from 27.3% in isolates from Germany to 13.1% in isolates from the UK), by 34.4% for all piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant isolates (n = 514) (increases ranged from 50.0% in isolates from Germany to 25.5% in isolates from Italy) and by 37.4% for all meropenem-resistant isolates (n = 227) (increases ranged from 61.9% in isolates from Germany to 21.3% in isolates from the UK).

Table 2.

In vitro susceptibility of all and β-lactam-resistant phenotypes of P. aeruginosa collected by the SMART global surveillance programme from 2018 to 2020 in Western Europe

| Percentage of isolates susceptible (number of susceptible isolates in TZP- and MEM-resistant isolate subsets) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype/country/region (n) | IMR | IMPa | MEM | FEPa | CAZa | TZPa | LVXa | AMK |

| All isolates | ||||||||

| France (360) | 96.1 | 78.6 | 84.2 | 86.7 | 83.3 | 82.5 | 76.1 | 93.3 |

| Germany (282) | 96.8 | 69.5 | 73.4 | 84.4 | 78.7 | 78.0 | 70.2 | 96.8 |

| Italy (328) | 89.6 | 73.2 | 74.4 | 80.2 | 72.6 | 68.9 | 65.2 | 89.9 |

| Portugal (165) | 87.9 | 67.9 | 69.7 | 73.9 | 67.3 | 68.5 | 69.1 | 92.1 |

| Spain (494) | 89.3 | 67.8 | 69.4 | 75.5 | 72.7 | 70.5 | 54.5 | 92.3 |

| UK (366) | 88.8 | 75.7 | 77.3 | 77.6 | 73.8 | 75.7 | 68.6 | 85.5 |

| Western Europe (1995) | 91.4 | 72.3 | 74.9 | 79.8 | 75.2 | 74.2 | 66.2 | 91.5 |

| TZP-resistant isolates | ||||||||

| France (63) | 84.1 (53) | 49.2 (31) | 46.0 (29) | 38.1 (24) | 20.6 (13) | 0 (0) | 50.8 (32) | 81.0 (51) |

| Germany (62) | 91.9 (57) | 41.9 (26) | 38.7 (24) | 35.5 (22) | 11.3 (7) | 0 (0) | 56.5 (35) | 87.1 (54) |

| Italy (102) | 71.6 (73) | 46.1 (47) | 42.2 (43) | 39.2 (40) | 20.6 (21) | 0 (0) | 37.3 (38) | 70.6 (72) |

| Portugal (52) | 69.2 (36) | 32.7 (17) | 38.5 (20) | 25.0 (13) | 3.9 (2) | 0 (0) | 34.6 (18) | 80.8 (42) |

| Spain (146) | 71.2 (104) | 32.9 (48) | 29.5 (43) | 26.0 (38) | 18.5 (27) | 0 (0) | 19.2 (28) | 80.8 (118) |

| UK (89) | 61.8 (55) | 36.0 (32) | 34.8 (31) | 25.8 (23) | 13.5 (12) | 0 (0) | 36.0 (32) | 61.8 (55) |

| Western Europe (514) | 73.5 (378) | 39.1 (201) | 37.0 (190) | 31.1 (160) | 16.0 (82) | 0 (0) | 35.6 (183) | 76.3 (392) |

| MEM-resistant isolates | ||||||||

| France (20) | 55.0 (11) | 0.0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20.0 (4) | 35.0 (7) | 25.0 (5) | 10.0 (2) | 50.0 (10) |

| Germany (21) | 71.4 (15) | 9.5 (2) | 0 (0) | 28.6 (6) | 33.3 (7) | 23.8 (5) | 23.8 (5) | 76.2 (16) |

| Italy (49) | 40.8 (20) | 0.0 (0) | 0 (0) | 30.6 (15) | 22.5 (11) | 18.4 (9) | 8.2 (4) | 46.9 (23) |

| Portugal (21) | 33.3 (7) | 4.8 (1) | 0 (0) | 14.3 (3) | 9.5 (2) | 4.8 (1) | 9.5 (2) | 61.9 (13) |

| Spain (69) | 42.0 (29) | 5.8 (4) | 0 (0) | 17.4 (12) | 21.7 (15) | 17.4 (12) | 5.8 (4) | 75.4 (52) |

| UK (47) | 21.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8.5 (4) | 14.9 (7) | 12.8 (6) | 14.9 (7) | 42.6 (20) |

| Western Europe (227) | 40.5 (92) | 3.1 (7) | 0 (0) | 19.4 (44) | 21.6 (49) | 16.7 (38) | 10.6 (24) | 59.0 (134) |

IMR, imipenem/relebactam; IMP, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; FEP, cefepime; CAZ, ceftazidime; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; LVX, levofloxacin; AMK, amikacin.

The results represent % ‘susceptible, increased exposure’ (SIE).

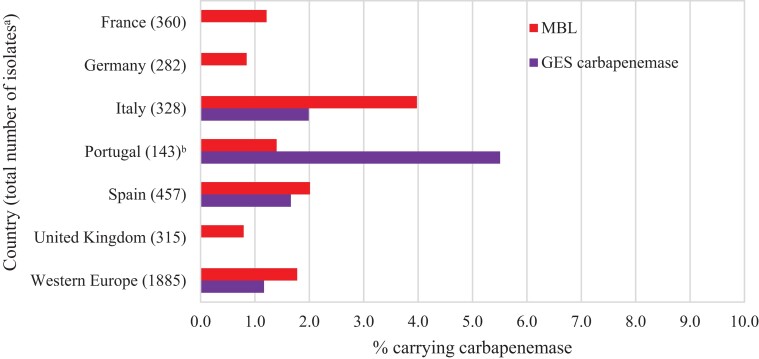

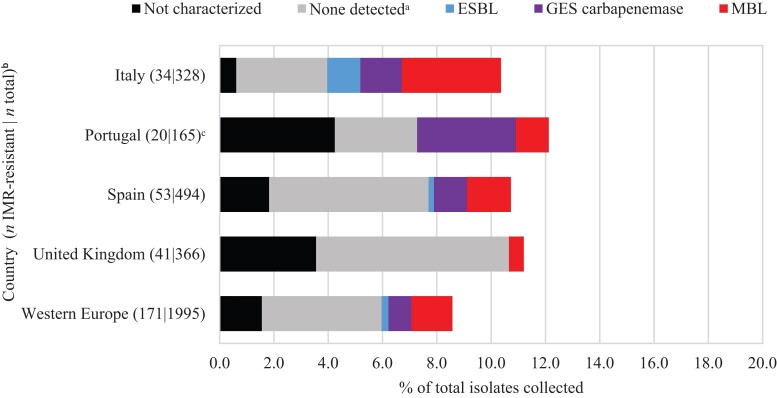

Overall, MBLs were carried by 1.8% of all P. aeruginosa isolates and 1.2% carried a GES carbapenemase (Figure 3). MBLs were carried by 4.0% and 2.0% of isolates from Italy and Spain, respectively, and were identified in every country. In Portugal, GES carbapenemases (carried by 5.5% of all isolates) were more common than MBLs (1.4%), unlike P. aeruginosa isolates from other countries. However, these isolates were all collected by one hospital laboratory site (of three sites) in Portugal and this rate may not reflect the actual prevalence in that country. Overall, MBLs were identified in 21.4% and GES carbapenemases in 12.1% of molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates (Figure 4). Acquired β-lactamases were not identified in 62.9% of molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates overall. Higher percentages of imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates with no β-lactamases detected were found in the UK (93%) and Spain (66%) than in Portugal (38%) and Italy (34%), where carbapenemases were more prevalent.

Figure 3.

Estimated carbapenemase rates among P. aeruginosa isolates. aExcludes 110 isolates collected in 2018 in Portugal (n = 22), Spain (n = 37) and the UK (n = 51) that were not available for molecular characterization. bAll isolates carrying GES carbapenemases were collected at one hospital laboratory site (of three) in Portugal.

Figure 4.

β-Lactamase gene carriage among imipenem/relebactam (IMR)-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates. Original-spectrum β-lactamases (e.g. TEM-1) and intrinsic AmpC found in P. aeruginosa (PDC) are not shown. aNo acquired β-lactamases detected. bOnly countries with at least 20 imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates are shown (not shown: France, n = 14; Germany, n = 9). cAll isolates carrying GES carbapenemases were collected at one hospital laboratory site (of three) in Portugal.

Acquired β-lactamases were not detected in 83% of all molecularly characterized piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant P. aeruginosa. This proportion was high for molecularly characterized piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates from every country [range 95% (UK) to 67% (Italy)] (Figure S3). Similar to piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant isolates, 72% of meropenem-resistant isolates of P. aeruginosa from all countries did not have an identifiable β-lactamase resistance mechanism identified [range 94% (UK) to 50% (Portugal)], suggesting other mechanisms (e.g. PDC derepression in combination with up-regulated efflux) were present in most isolates (Figure S4).

Against ICU and non-ICU P. aeruginosa isolates, differences in percent susceptible values were <5% for imipenem/relebactam and all other agents except levofloxacin (10.1%) and amikacin (7.1%) (Table S3). A uniformity or pattern in the differences in percent susceptible values was not evident for ICU and non-ICU patient isolates. Against isolates collected from patients hospitalized for <48 and ≥48 h at the time of specimen collection, differences of <5% were also observed in imipenem/relebactam percent susceptible values. For the other agents, differences were larger for this stratification (than patient location at the time of sample collection), with meropenem (9.2%), imipenem (8.8%), piperacillin/tazobactam (8.1%) and ceftazidime (6.2%) showing differences of >5%. Overall, percent susceptible values for all agents were higher in Western Europe isolates from patients hospitalized <48 h at the time of specimen collection, with the exception of levofloxacin and amikacin. Again, some individual country-to-country variation was observed in percent susceptible values for P. aeruginosa isolates for both ward type and length of stay at the time of specimen collection parameters.

Of the P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2020, 6.9% (49/708) were imipenem/relebactam resistant. Of these imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates, 67% were molecularly characterized (33/49). Figure S5 shows acquired β-lactamases and oprD status among molecularly characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates collected in 2020; 90.9% (30/33) of imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates were OprD deficient. Isolates in which no acquired β-lactamases were detected and OprD deficiency was not identified made up only 6.1% of all characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates collected in 2020.

Discussion

In 2018–20, 99% of 4414 NME isolates and 91% of 1995 P. aeruginosa isolates collected through the SMART global surveillance programme from patients with lower RTIs in Western Europe were imipenem/relebactam susceptible (Table 1, Table 2). Relebactam increased the susceptibility to imipenem for all isolates of NME by 3.2% and for all isolates of P. aeruginosa by 19.1% compared with imipenem alone; by 14.1% (NME) and 34.4% (P. aeruginosa) for piperacillin/tazobactam-resistant isolates; and by 81.1% (NME) and 37.4% (P. aeruginosa) for meropenem-resistant isolates.

The frequency of carbapenem-resistant, MDR and difficult-to-treat resistant (DTR) Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa causing HAP, VAP and other infections is increasing globally but may vary between countries, regions, hospitals, different patient populations within a hospital (e.g. inside versus outside ICUs), and may depend upon the patient length of stay in a hospital.9,10,13–17 In the current study of lower RTI isolates collected by hospital laboratories in six Western European countries during 2018–20, 2.4% of NME isolates were meropenem-resistant; most meropenem-resistant NME isolates (80.2%) were from only two countries [Italy (9.0% of NME isolates were meropenem-resistant); Portugal (4.4%)] (Table 1). Very low numbers of meropenem-resistant NME isolates (<1.5% of isolates) were identified in the other four countries (France, Germany, Spain, UK). Meropenem-resistant P. aeruginosa were more common than meropenem-resistant NME, and ranged from 5.6% of isolates from France to 14.9% of isolates from Italy (Table 2).

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa most commonly result from acquired carbapenemases (serine-β-lactamases or MBLs) and/or from a combination of AmpC and/or ESBL expression and porin loss and/or up-regulated efflux.4,5,13,14,18–22 Carbapenemases frequently demonstrate geographical variation in prevalence and composition.9,13–16,18,19,21,22 In the current study, an estimated 0.5% of all NME isolates from Western Europe carried an MBL, 0.9% carried an OXA-48-like carbapenemase (without a co-carried MBL) and 2.8% carried a KPC (without other co-carried carbapenemases) (Figure 1). The very high percentage of susceptibility of NME to imipenem/relebactam (99%) is attributable to the low numbers of isolates carrying Ambler class B and class D carbapenemases, against which relebactam is inactive.4 MBL and OXA-48-like carbapenemase carriage rates were highest in isolates from Spain (1.3% and 2.1%, respectively) and Italy (1.0% and 1.1%). KPC carriage rates were highest in Italy (10.6%) and Portugal (5.9%). MBLs were carried by 1.8% of all P. aeruginosa isolates and 1.2% carried GES carbapenemases (Figure 3); GES carbapenemases have been observed in both imipenem/relebactam-susceptible and imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates of P. aeruginosa.5 MBLs were most commonly carried by P. aeruginosa isolates from Italy (4.0%) and Spain (2.0%) but were identified in every country.

In P. aeruginosa, resistance to imipenem is more commonly associated with derepression of PDC (AmpC) together with OprD (porin) loss whereas resistance to meropenem arises due to up-regulation of efflux pumps (e.g. MexAB-OprM) in combination with PDC derepression.9,19,20 Imipenem is not subject to efflux. Imipenem/relebactam inhibits carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa resulting from porin loss or efflux combined with PDC overexpression.4,5 In the current study, the majority (63%) of characterized imipenem/relebactam-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates did not carry an acquired β-lactamase (and the mechanism of resistance remained undefined); 34% of characterized isolates carried a carbapenemase (Figure 4). However, when imipenem/relebactam-resistant P. aeruginosa from 2020 were studied using WGS, 91% of imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates were OprD deficient (Figure S5) suggesting that loss of OprD likely contributed to imipenem/relebactam non-susceptibility in the majority of imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates. Given that imipenem is known to be a strong inducer of PDC, the imipenem/relebactam-resistant isolates with no other mechanisms could be the result of OprD loss coupled with elevated PDC expression. Unidentified class B or class D β-lactamases may have also contributed to imipenem/relebactam-resistant phenotypes but this is unlikely.

The strengths of the current study are that it collected isolates from at least three sites in six countries according to a consistent protocol and employed reference broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing and molecular testing performed in a central laboratory. Its limitations include that the limited number of medical centres participating in each country was not necessarily representative of the whole country. Furthermore, the number of sites and collected isolates varied across countries and did not necessarily reflect the country’s population size. Changes in study participation by individual medical centres over the 3 years surveyed also occurred. PDC gene expression levels were not assessed.

In conclusion, in 2018–20, 99% of NME and 91% of P. aeruginosa from Western Europe were imipenem/relebactam susceptible, 96% (NME) and 75% (P. aeruginosa) were meropenem susceptible, and 78% (NME) and 74% of (P. aeruginosa) were piperacillin/tazobactam susceptible. MBL carriage rates among NME (0.5%) and P. aeruginosa (1.8%) were very low and only 0.9% of NME carried an OXA-48-like carbapenemase (without a co-carried MBL). Imipenem/relebactam appears to be a potential treatment option for lower RTIs caused by piperacillin/tazobactam- and meropenem-resistant NME and P. aeruginosa in Western Europe.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all laboratory participants for their contributions to the SMART global surveillance programme.

Contributor Information

James A Karlowsky, IHMA, 2122 Palmer Drive, Schaumburg, IL, 60173, USA; Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Room 543-745 Bannatyne Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3E 0J9, Canada.

Sibylle H Lob, IHMA, 2122 Palmer Drive, Schaumburg, IL, 60173, USA.

Brune Akrich, MSD, 10-12 Cr Michelet, Puteaux, 92800, France.

C Andrew DeRyke, Merck & Co., Inc., 126 East Lincoln Avenue, Rahway, NJ, 07065, USA.

Fakhar Siddiqui, Merck & Co., Inc., 126 East Lincoln Avenue, Rahway, NJ, 07065, USA.

Katherine Young, Merck & Co., Inc., 126 East Lincoln Avenue, Rahway, NJ, 07065, USA.

Mary R Motyl, Merck & Co., Inc., 126 East Lincoln Avenue, Rahway, NJ, 07065, USA.

Stephen P Hawser, IHMA, Rte. de l’Ile-au-Bois 1A, 1870 Monthey, Switzerland.

Daniel F Sahm, IHMA, 2122 Palmer Drive, Schaumburg, IL, 60173, USA.

Funding

Funding for this research, which included compensation for services related to preparing this manuscript, was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Transparency declarations

S.H.L., S.P.H. and D.F.S. work for IHMA, which receives funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA for the SMART global surveillance programme. J.A.K. is a consultant to IHMA. B.A., C.A.D., F.S., K.Y. and M.R.M. are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and own stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. The IHMA authors and J.A.K. do not have personal financial interests in the sponsor of this paper (Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA).

Supplementary data

Figures S1 to S5 and Tables S1 to S3 are available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online.

References

- 1. Klompas M. In: File TM ed. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Microbiology, and Diagnosis of Hospital-Acquired and Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Adults. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas Met al. . Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63: e61–111. 10.1093/cid/ciw353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merck & Co. Inc . RECARBRIO™ (imipenem, cilastatin, and relebactam) for injection, for intravenous use, package insert. 2021. https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/r/recarbrio/recarbrio_pi.pdf.

- 4. Livermore DM, Warner M, Mushtaq S. Activity of MK-7655 combined with imipenem against Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 2286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Young K, Painter RE, Raghoobar Set al. . In vitro studies evaluating the activity of imipenem in combination with relebactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol 2019; 19: 150. 10.1186/s12866-019-1522-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. CLSI . Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically—Eleventh Edition: M07. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. CLSI . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—Thirty-First Edition: M100. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8. EUCAST . Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, Version 11.0.2021. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_11.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- 9. Nichols WW, de Jonge BLM, Kazmierczak KMet al. . In vitro susceptibility of global surveillance isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to ceftazidime-avibactam (INFORM 2012 to 2014). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4743–9. 10.1128/AAC.00220-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lob SH, Biedenbach DJ, Badal REet al. . Antimicrobial resistance and resistance mechanisms of Enterobacteriaceae in ICU and non-ICU wards in Europe and North America: SMART 2011–2013. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2015; 3: 190–7. 10.1016/j.jgar.2015.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Estabrook M, Kazmierczak KM, Wise Met al. . Molecular characterization of clinical isolates of Enterobacterales with elevated MIC values for aztreonam-avibactam from the INFORM global surveillance study, 2012–2017. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021; 24: 316–20. 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino Set al. . Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 2640–44. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bush K, Bradford PA. Epidemiology of β-lactamase-producing pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020; 33: e00047-19. 10.1128/CMR.00047-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Jonge BLM, Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KMet al. . In vitro susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected during the INFORM global surveillance study (2012 to 2014). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 3163–9. 10.1128/AAC.03042-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castanheira M, Deshpande L, Mendes REet al. . Variations in the occurrence of resistance phenotypes and carbapenemase genes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates in 20 years of the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6: S23–33. 10.1093/ofid/ofy347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spiliopoulou I, Kazmierczak K, Stone GG. In vitro activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against isolates of carbapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae collected during the INFORM global surveillance programme (2015–2017). J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 384–91. 10.1093/jac/dkz456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lob SH, Hoban DJ, Young Ket al. . Activity of imipenem/relebactam against Gram-negative bacilli from global ICU and non-ICU wards: SMART 2015–2016. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2018; 15: 12–9. 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kazmierczak KM, Karlowsky JA, de Jonge BLMet al. . Epidemiology of carbapenem resistance determinants identified in meropenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterales collected as part of a global surveillance program, 2012 to 2017. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021; 65: e02000-20. 10.1128/AAC.02000-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kazmierczak KM, de Jonge BLM, Stone GGet al. . Longitudinal analysis of ESBL and carbapenemase carriage among Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in Europe as part of the international network for optimal resistance monitoring (INFORM) global surveillance programme, 2013–2017. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 1165–73. 10.1093/jac/dkz571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cabot G, Zamorano L, Moyà Bet al. . Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa antimicrobial resistance and fitness under low and high mutation rates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 1767–78. 10.1128/AAC.02676-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kazmierczak KM, Rabine S, Hackel Met al. . Multiyear, multinational survey of the incidence and global distribution of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 1067–78. 10.1128/AAC.02379-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kazmierczak KM, Biedenbach DJ, Hackel Met al. . Global dissemination of blaKPC into bacterial species beyond Klebsiella pneumoniae and in vitro susceptibility to ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4490–500. 10.1128/AAC.00107-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.