Abstract

Leaf inclination is one of the most important components of the ideal architecture, which effects yield gain. Leaf inclination was shown that is mainly regulated by brassinosteroid (BR) and auxin signaling. Here, we reveal a novel regulator of leaf inclination, auxin transporter OsPIN1b. Two CRISPR-Cas9 homozygous mutants, ospin1b-1 and ospin1b-2, with smaller leaf inclination compared to the wild-type, Nipponbare (WT/NIP), while overexpression lines, OE-OsPIN1b-1 and OE-OsPIN1b-2 have opposite phenotype. Further cell biological observation showed that in the adaxial region, OE-OsPIN1b-1 has significant bulge compared to WT/NIP and ospin1b-1, indicating that the increase in the adaxial cell division results in the enlarging of the leaf inclination in OE-OsPIN1b-1. The OsPIN1b was localized on the plasma membrane, and the free IAA contents in the lamina joint of ospin1b mutants were significantly increased while they were decreased in OE-OsPIN1b lines, suggesting that OsPIN1b might action an auxin transporter such as AtPIN1 to alter IAA content and leaf inclination. Furthermore, the OsPIN1b expression was induced by exogenous epibrassinolide (24-eBL) and IAA, and ospin1b mutants are insensitive to BR or IAA treatment, indicating that the effecting leaf inclination is regulated by OsPIN1b. This study contributes a new gene resource for molecular design breeding of rice architecture.

Keywords: auxin, auxin transporter, BR, leaf inclination, OsPIN1b, rice

1. Introduction

Lamina joint inclination (leaf inclination/angle) between the lamina and vertical culm is an important agronomic trait in rice (Oryza sativa L.), which is considered to reflect the status of rice cultivation and grain yield [1]. In rice, leaf erectness has an important effect on the capture of sunlight and CO2 diffusion efficiency. The reduction in leaf inclination enables a single leaf to capture sunlight on both sides, and reduces mutual shielding of leaves, improves light transmittance, and has stronger solar absorption efficiency, which is more suitable for high-density planting [2]. The lamina joint is a ring-shaped tissue outside the joint of the leaf blade and leaf sheath, which influences orientation of extension and leaf inclination, and provides mechanical strength for the shape of leaf inclination. The cells on the adaxial side of the lamina joint play an essential role in adjusting leaf inclination [3,4]. For instance, the increased growth of cells on the adaxial side of the lamina joint in ili1-D causes an enlarged lamina inclination phenotype [5]. Conversely, CYC U4;1 promotes leaf erectness by controlling the abaxial sclerenchyma cell proliferation [6].

By previous report, BR biosynthesis or signaling transduction contributes significantly to regulating the leaf inclination. Deficient mutant of OsDWARF4, a rate-limiting gene in BR biosynthesis, displayed erect leaf inclination phenotype and enhanced grain yields [2]. The increased leaf erectness phenotypes also were found in several loss of function mutants of BR biosynthesis-related genes, including brassinosteroid-deficient dwarf1 (brd1, deficiency of OsDWARF), ebisu dwarf (d2, deficiency of D2/CYD90D2), and dwarf11 (d11, deficiency of D11/CYP724B1) [7,8]. Furthermore, BR signaling defective mutant, d61, was also similar to mutant of rice BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (OsBRI1 encodes a putative BR receptor kinase), which have erect leaves [4]. The lamina joint bending of RNAi mutant of the transcription factor OsBZR1 involved in the BR signaling pathway, was reduced [9].

In addition to brassinosteroid (BR), auxin signaling also plays a crucial role in controlling leaf inclination, which may be closely related to differential cell elongation in adaxial and abaxial in the lamina joint [6,10,11,12]. In auxin signaling, auxin early response genes, including the OsIAA, OsGH3, and OsSAUR family were reported to be related to regulating leaf inclination. OsIAA1-overexpressed plant increased the lamina joint bending and reduced the plant height [11,13,14,15,16]. Further study demonstrated that an EMBRYONIC FLOWER 1-like (EMF1-like) protein encoded by dwarf and small grain size 1 (DS1), physically interacted with OsARF11 to positively co-regulate plant height and leaf angle [17]. Recent study indicated that the auxin-induced expression of ILA1 gene is dependent on OsARF6 and OsARF17 binding to the promoter region of ILA1 [18]. Loss-of-function double osarf6 osarf17 mutants displayed reduced secondary cell wall thickness of lamina joint sclerenchyma cells due to the decreased expression level of ILA1, affecting the support weight of the flag leaf blade, finally an enlarged flag leaf angle and reduced grain yield under dense planting conditions. As the major biosynthetic pathway of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the indole-3-pyruvate (IPA) pathway, is catalyzed by the TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE of ARA-BIDOPSIS (TAA) and YUCCA (YUC) families. FISH BONE (FIB) encodes a homologue of the TAA protein, which plays a negative role in leaf inclination [19]. Loss-function of FIB leads to decreased IAA levels and altered auxin polar transport activity, resulting in increased leaf inclination and smaller leaves.

In addition, polar auxin transport (PAT) regulates auxin distribution, which is largely dependent on the three protein families, including influx carrier AUXIN/LIKE AUXIN (AUX/LAX), efflux carrier PIN-FORMED (PIN), and bidirectional carrier ATP-binding cassette family B (ABCB)/P-glycoprotein (PGP) [20,21,22,23,24,25]. The PIN proteins play crucial roles in direction and rate of auxin flow [26]. However, the biological function of auxin transporters regulating leaf inclination is not yet reported. In Arabidopsis thaliana, PIN1 is the first reported auxin efflux carrier, and the atpin1 pin-formed inflorescence and defective development of vascular tissue [20,27,28,29,30]. Among the twelve members of PIN in rice, OsPIN1 is composed of four members, OsPIN1a, OsPIN1b, OsPIN1c, and OsPIN1d [31]. It was reported that OsPIN1b functions in regulating tillering, adventitious root emergence, and seminal roots elongation [32,33]. OsPIN2-mediated auxin transport from the shoot to the root-shoot junction, resulted in the reduced plant height, the increased tiller numbers, and the increased tiller angle [34]. OsPIN5b is located in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and involves in intracellular auxin transport to regulate tiller number, panicles length, and yield [35,36]. OsPIN9 was involved in the development of tiller bud [37]. OsPIN3t (OsPIN10a/OsPIN3a) was connected with auxin polar transport and drought response [31,38,39]. In this study, we revealed that the homozygous ospin1b mutants have smaller lamina inclination, whereas OsPIN1b overexpression lines have larger lamina inclination compared to WT/NIP. Additionally, OsPIN1b responded to BR and auxin signaling, suggesting that OsPIN1b plays a role in regulating lamina inclination under crosstalk between both signaling.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of ospin1b Mutants and OsPIN1b Overexpression Lines

By previous reports, OsPIN1b showed that it regulates root, shoot inflorescence development, and tillering [32,33]. However, the other roles of OsPIN1b in growth and development of rice remain unknown. In order to investigate thoroughly the biological function of OsPIN1b, we constructed two independent mutant lines of ospin1b, ospin1b-1, and ospin1b-2 by the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing system. Two specific guide RNA (gRNA) sequences were designed in the first exon, acting as gene edit targets (Supplementary Figure S1A). The gRNA1 targeting sequence deleted one cytosine “C” at 418 bp of OsPIN1b open reading frame in ospin1b-1, while it inserted one cytosine “C” at 491 bp in the targeting sequence of gRNA2, and resulted in the variation in amino acid sequence and premature termination of translation. For ospin1b-2, in gRNA1 targeting sites inserted one adenine “A” at 418 bp, and inserted one thymine “T” at 494 bp in the targeting sequence of gRNA2, which leaded to similar consequences with ospin1b-1 (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure S1B–D). Furthermore, OsPIN1b overexpression lines were constructed using pCAMBIA1300-sGFP (Figure 1B), and two homozygous OE-OsPIN1b-1 and OE-OsPIN1b-2, which have a 1.5-fold and 2.5-fold expression level compared to OsPIN1b of WT/NIP by RT-qPCR analysis (Figure 1E), were used in subsequent studies. By statistical analysis, the leaf inclinations in ospin1b mutants were reduced ~30%, while in OsPIN1b, overexpression lines were increased ~140% compared to WT/NIP (Figure 1C,D). These results suggest that OsPIN1b might contribute to regulating leaf inclination.

Figure 1.

Characterization of ospin1b mutants and OsPIN1b overexpression lines. (A) Construction of two ospin1b mutants by CRISPR-Cas9. Gray boxes, black lines, and white boxes represent exons, introns, and untranslated region, respectively; + and ▼ indicates the insertion sites in ospin1b mutants, − and ▼ indicates the deletion site in ospin1b mutants. ATG and TGA presents start codon and stop codon. (B) Structure of OsPIN1b overexpression vector pCAMBIA1300-sGFP. (C,D) Phenotypes and statistics analysis of the leaf inclination in the second leaf of WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OsPIN1b overexpression lines for 3-week-old seedling. The angle between the red lines represents the leaf inclination. The statistical data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and * indicates the significant difference among WT/NIP, ospin1b, and OE-OsPIN1b (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). Scale bar = 5 cm. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of OsPIN1b expression in WT/NIP and OsPIN1b overexpression lines. Three independent biological replicas were performed here. OsACTIN was used as an internal control. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and * indicates the significant differences between WT/NIP and OE-OsPIN1b (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test).

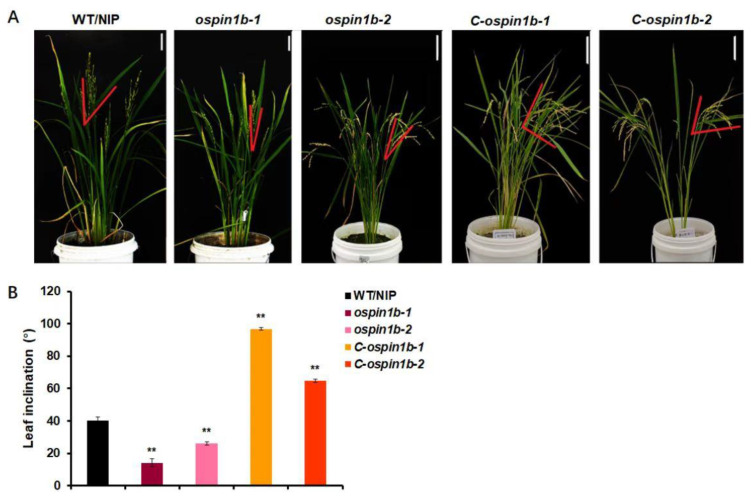

2.2. Characterization of Complementary ospin1b Lines

To further confirm the relationship between OsPIN1b and leaf inclination phenotype in rice, the complementary ospin1b lines, C-ospin1b-1 and C-ospin1b-2, were constructed by transforming 35S:OsPIN1b-sGFP into ospin1b-1 or ospin1b-2. Compared with the ospin1b mutants, the flag leaf inclination of C-ospin1b-1 or C-ospin1b-2 were significantly increased (Figure 2A,B), indicating that OsPIN1b rescued the phenotype of less leaf inclination of ospin1b-1 or ospin1b-2. The results further provide genetic evidence for OsPIN1b controlling leaf inclination.

Figure 2.

Identification of complementary ospin1b lines. (A,B) The phenotype and statistics analysis of flag leaf inclination in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, complementary ospin1b lines for 4-month-old, C-ospin1b-1, and C-ospin1b-2. The angle between the red lines represents the flag leaf inclination. The statistical data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and ** indicates significant differences between WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, C-ospin1b-1, and C-ospin1b-2 (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). Scale bar = 10 cm.

2.3. OsPIN1b Constitutively Expressed in Each Tissue Including Lamina Joint

To further investigate whether OsPIN1b is involved in lamina joint development to regulate leaf inclination, the expression pattern of OsPIN1b was observed using ProOsPIN1b-GUS transgenic rice lines. GUS staining results show that OsPIN1b is expressed in each tissue, including roots, stem, leaf, leaf sheath, flower, and seed (Figure 3A–G); qRT-PCR results also showed that OsPIN1b was widely expressed in each organ or tissue, which was consistent with GUS staining. Additionally, the expression level of OsPIN1b was significantly increased in leaf and young panicle (Figure 3H). Furthermore, OsPIN1b was expressed in lamina joint from one to four weeks (Figure 3I), suggesting that OsPIN1b might be involved in the regulation of each stage of leaf inclination in rice.

Figure 3.

Expression pattern of OsPIN1b gene. GUS staining in each tissue of ProOsPIN1b: GUS transgenic rice. Ten biological replicas were analyzed for each tissue. Scale bars = 1 mm. (A) Maturation region of primary root, (B) elongation zone, meristem zone, and root cap of primary root, (C) stem, (D) leaf, (E) transverse section of leaf sheath, (F) floral organ, (G) the germinated seed for 3 days. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of relative expression level of OsPIN1b in different tissues of WT/NIP. R: root; S: stem; L: leaf; R-S: root-stem junction; FL: flag leaf; YP: Young panicle. OsACTIN was used as an internal control. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and asterisks indicate significant differences in different tissues (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). (I) qRT-PCR analysis of relative expression level of OsPIN1b in lamina joint at different stages of WT/NIP from one to four weeks. The three independent biological repeats were performed in the qRT-PCR analysis. OsACTIN was used as an internal control. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and asterisks indicate the significant differences in different stages (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test).

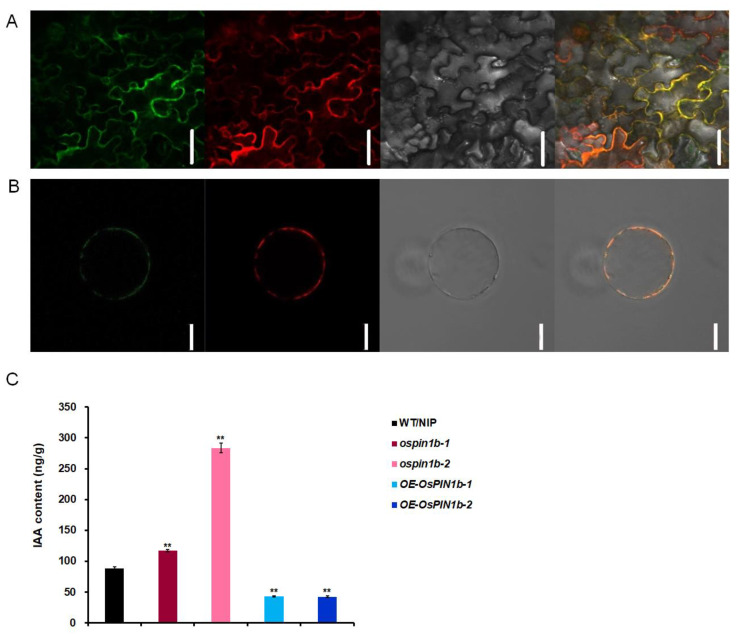

2.4. OsPIN1b Localized on Plasma Membrane and OsPIN1b Reduced the Free IAA Accumulation

In Arabidopsis, hydrophilic analysis of PIN demonstrates that there is a fairly high degree of similarity in both transmembrane hydrophobic domains located at the N- and C-terminus of the proteins, while high differentiation in the central hydrophilic region [40]. Additionally, previous research established that OsPIN proteins have a similar structure to AtPIN [31]. To investigate the function of OsPIN1b, we performed transmembrane structural domain prediction of OsPIN1b. The results show that OsPIN1b possesses a central segment with a long hydrophilic loop and two transmembrane hydrophobic regions in the N-terminal and C-terminus of the protein, which are consistent with the structure of a PIN carrier protein (Supplementary Figure S2). To further confirm whether OsPIN1b is located on the plasma membrane, 35S: OsPIN1b-sGFP and the plasma membrane marker pm-rbCD3-1008 were transiently co-expressed and transformed into the leaf epidermal cells of Nicotiana benthamiana and rice protoplasts [41]. Both experiments indicate that OsPIN1b is actually localized on the plasma membrane (Figure 4A,B). Taken together, these results suggest that OsPIN1b might have an auxin transport function similar to AtPIN1, which was characterized as a first putative auxin export carrier [29].

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of OsPIN1b and auxin contents in lamina joints. (A,B) 35S:OsPIN1b-sGFP fusion construct and plasma membrane marker pm-rbCD3-1008 were simultaneously co-expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells (upper) and rice protoplasts (lower). From left to right, represents green fluorescence of 35S:OsPIN1b-sGFP, red fluorescence of membrane marker pm-rbCD3-1008, bright-field images, and yellow merged fluorescence, respectively. Scale bars = 10 μm. (C) Auxin contents in lamina joints of 7-day-old WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2. The three biological repeats were used in these experiments. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and asterisks indicate the significant differences in the above-mentioned lines (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test).

In order to explore if OsPIN1b affects the leaf inclination through altering of OsPIN1b-mediated IAA contents, we analyzed free IAA contents in the lamina joints of WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OsPIN1b overexpressed lines at one week of the seedling stage. The IAA content of lamina joint of ospin1b-1 and ospin1b-2 was increased by 32 and 220%, respectively, compared with the WT/NIP, while the IAA content in lamina joint of OE-OsPIN1b-1 and OE-OsPIN1b-2 were decreased compared with WT/NIP (Figure 4C). The results suggest that the OsPIN1b functions in decreasing the free IAA accumulation in lamina joint, which is similar with OsARF19 [42].

2.5. OsPIN1b Enhances Adaxial Cell Division of Pulvinus to Increase Leaf Inclination

Increasing evidences show that the altered pulvinus development effects leaf inclination [4,43]. In order to reveal how OsPIN1b controls leaf inclination on the cell level, the flag leaf inclination and the adaxial and abaxial surface of pulvinus were observed and measured in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2. The results show that the flag leaf inclination of the mutant ospin1b-1 and ospin1b-2 was smaller, and the length of the adaxial side of pulvinus in ospin1b-1 or ospin1b-2 was shorter, whereas flag leaf inclination and adaxial length of pulvinus showed opposite phenotypes in OE-OsPIN1b, compared to in WT/NIP (Figure 5A–C). To further confirm the pulvinus morphology, the adaxial side of pulvinus in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1 and OE-OsPIN1b-1 were observed using scanning electron microscopy. As showed in Figure 5D, the adaxial region of OE-OsPIN1b-1 has significant bulge compared to WT/NIP and ospin1b-1. These results further support that the enlarging leaf inclination in OE-OsPIN1b-1 is due to the increase in the adaxial cell division of its pulvinus. By previous reports, the asymmetric proliferation and expansion of adaxial and abaxial cell of pulvinus leaded the variation in leaf inclination, which were induced by BR or IAA frequently, suggesting that OsPIN1b-mediated leaf inclination variation might also be associated with BR or IAA [5,6,42,44].

Figure 5.

OsPIN1b regulates pulvinus. (A) Pulvinus of flag leaf of WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2. (B) The statistics analysis of flag leaf inclination in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2 lines. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3). The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and asterisk indicates the significant differences (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). (C) The statistics analysis of the adaxial and abaxial side of pulvinus length in of WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2. Scale bar =1 mm. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3) and asterisk indicates the significant differences (** p < 0.01; Student’s t-test). (D) The adaxial surface of the pulvinus in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1 and OE-OsPIN1b-1 by SEM. The red box indicates cells on the adaxial surface of the pulvinus in WT/NIP, ospin1b and OE-OsPIN1b. Scale bar = 1 mm.

2.6. BR or Auxin Induces OsPIN1b Expression, and the Expression of the Genes Related Both Signaling Reduces in ospin1b Mutants

BR and auxin are the two important phytohormones affecting leaf inclination by previous report. Most of the mutants related auxin signaling with altered leaf inclination also showed BR response. To clarify whether OsPIN1b regulating leaf inclination is also involved in BR and auxin signaling, first, the expression level of OsPIN1b in WT/NIP seedlings were tested with the different time under these phytohormones treatments. The results show that OsPIN1b was induced by BR and IAA, indicating that the expression of OsPIN1b in rice might be regulated by these signaling pathways (Figure 6A). Then, the expression levels of the five genes related BR and auxin signaling or biosynthesis, OsBRI1, D2, D11, OsARF19, and OsIAA1 were detected in WT/NIP, ospin1b, and OE-OsPIN1b. OsBRI1, a membrane-bound receptor kinase, with leucine rich repeat (LRR) perceives BR signaling [45,46,47,48]. Compared to wild-type, loss-of-function mutants of OsBRI1, d61-1 and d61-2 are insensitive to BR, with erect leaves and dwarf culms [4,49]. Shrinking leaf inclination phenotypes were observed in deletion mutants of BR biosynthesis genes D2 (CYP90D2) and D11 (CYP724B1) [8,50]. Compared with the wild type, the OsBRI1, D2 and D11 expression levels in the lamina joint of ospin1b mutants was significantly down-regulated, and the opposite trend was observed in OsPIN1b overexpression lines (Figure 6B), suggesting that OsPIN1b regulating leaf inclination was involved in BR signaling. In addition, the expressions of the auxin early response gene OsIAA1 and OsARF19 encoding auxin response factor, which was included in auxin signaling (Figure 6B), was significantly up-regulated in OsPIN1b overexpression lines; and their overexpression lines with increased leaf inclination [14,42] were consistent of OE-OsPIN1b lines, implying that OsPIN1b might also participate in the auxin signal transduction pathway.

Figure 6.

OsPIN1b regulates leaf inclination by activating BR and auxin signaling. (A) qRT-RCR analysis of the OsPIN1b expression under BR and IAA treatments with different time. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3), ** indicate significant difference at p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (B) The expression level of genes related to biosynthesis and signal transduction of BR and auxin in rice lamina joints of WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2 by qRT-RCR. OsACTIN was used as an internal control. The data are mean ± SD (n = 3), * indicates significant difference at p < 0.05, and ** indicates statistical significance at p < 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

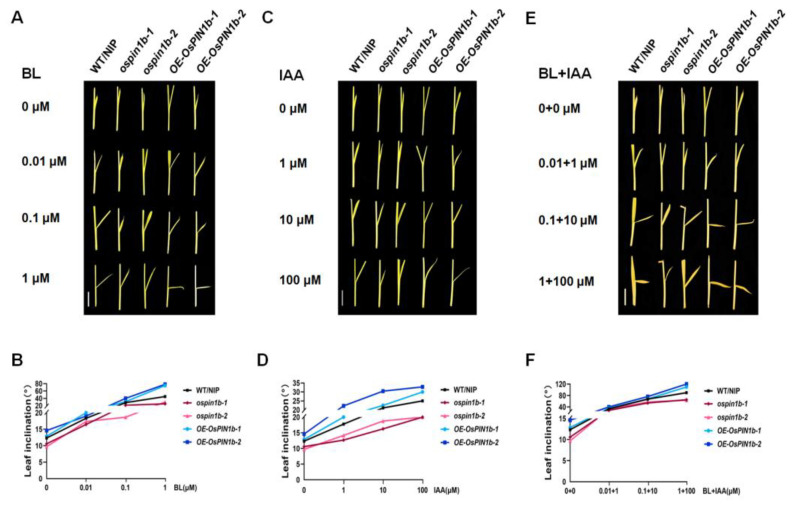

2.7. The Decreased Sensitivity to BR and IAA in ospin1b Mutants

To further understand if OsPIN1b controls leaf inclination through the BR and auxin pathway, the lamina inclinations of the WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants and OE-OsPIN1b lines were measured under BL, IAA, and BL + IAA treatments, respectively. Phenotypic observation showed that under BL treatment, leaf inclination of WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants and OE-OsPIN1b lines were more enlarged than control, with the increasing in BL concentration (Figure 7A). In particular, leaf inclination of WT/NIP increased by 264%, ospin1b mutants increased by 173%, and OE-OsPIN1b increased by 460% under 1 μM of BL concentration compared with non-BL treatment (Figure 7B). These results suggest that the sensitivity of ospin1b mutants to BR was reduced in terms of leaf inclination, which was caused by the loss of OsPIN1b function. On the other hand, the leaf inclination of WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OE-OsPIN1b lines were effectively increased with the increase in IAA concentration (Figure 7C). Under 100 μM IAA, the mean leaf inclination of WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OE-OsPIN1b lines were increased by nearly 102%, 88%, and 129%, respectively, compared with each untreated sample (Figure 7D). The leaf inclination of ospin1b mutants also showed that the decrease in sensitivity to IAA. Furthermore, the leaf inclination of each line to the application of both BL and IAA was much larger than single BL or IAA (Figure 7E,F). Distinctly, after applied 1 + 100 μM of BL and IAA together, the leaf inclinations were increased nearly 629% and 738% in WT/NIP and OE-OsPIN1b, while the increase is less than 540% in ospin1b mutants. Overall, these results suggest that OsPIN1b might participate in crosstalk between BR and auxin signaling in regulating leaf inclination.

Figure 7.

Variation in leaf inclination by BR and IAA treatments. (A) Leaf inclination response to 24-eBL treatment in WT/NIP, ospin1b-1, ospin1b-2, OE-OsPIN1b-1, and OE-OsPIN1b-2 for 7-day-old seedling. (B) The statistical analysis of (A). (C) Leaf inclination response to IAA treatment. (D) The statistical analysis of (C). (E) Leaf inclination response to 24-eBL + IAA treatment. The concentrations of BL + IAA from top to bottom were 0 + 0, 0.01 + 1, 0.1 + 10, and 1 + 100 µM, respectively. (F) The statistical analysis of (E). The data in (B,D,F) are mean ± SD (n = 10 independent plants). Scale bars = 1 cm.

In addition, according to a previous BR sensitivity report, coleoptile elongation and root length were promoted by BR treatment in rice [4]. Hence, we compared the length of coleoptiles and roots in WT/NIP, ospin1b, and OE-OsPIN1b lines under BR treatment (Supplementary Figure S3). All lines increased the coleoptile length and shortened the root length, and showed a dose-dependent pattern under 24-eBL treatment. However, the ospin1b mutants was less sensitive to 24-eBL than WT/NIP or the OsPIN1b overexpression lines, especially in their roots in response to BR. Taken together, the above data further confirm that the other biofunctions of OsPIN1b are also related to BR signaling.

3. Discussion

3.1. OsPIN1b Plays a Positive Role in Enlarging Leaf Inclination via Regulating Auxin Transport in Rice

The distribution and level of auxin in plant tissues play an important role in plant growth and development [51]. As an auxin transporter, the PIN family mainly facilitates auxin distribution and flow direction [26,27,28,52,53]. The loss of function of auxin transporters may lead to abnormal plant phenotypes [54]. This study revealed that the IAA content in lamina joint of ospin1b-1 and ospin1b-2 was significantly increased, while decreased in OE-OsPIN1b lines (Figure 4C). The leaf inclination in ospin1b mutants was reduced, while in OsPIN1b, overexpression lines were increased compared to WT/NIP (Figure 1C,D). The above results imply that OsPIN1b positively regulates leaf inclination through altering auxin transport. Previous studies of auxin transporters in rice mostly focused on root development and tiller, our study demonstrated that OsPIN1b also plays a role in regulating rice leaf inclination [24,25,33]. Recently, the Gmpin1abc and Gmpin1bc mutant edited by CRISPR-Cas9 showed a compact architecture with smaller petiole angles than wild-type plants, which is similar with our results [55].

3.2. OsPIN1b Participates in Adaxial Cell Enlargement of Lamina Joint through Complex Regulatory Mechanism of Auxin and BR

In our study, the enlarging of OE-OsPIN1b leaf inclination is caused by the increasing in adaxial cell numbers in the lamina joint, while the phenotype in the ospin1b mutant line was opposite (Figure 5C). Previous studies showed that BR and IAA both regulate leaf inclination by changing the unbalanced development between the adaxial and abaxial cells of the lamina joint. In rice, INCLINATION1 (ILI1) and ILI1 binding bHLH (IBH1) antagonistically regulate the adaxial cell elongation in lamina joint by interacting with OsBZR1, a transcription factor involved in BR signaling [5]. The U-type cyclin CYC U4;1 was highly expressed in the lamina joint. The proliferation of sclerenchyma cells at the abaxial side of lamina joint is regulated by the BR regulation pathway, which leads to the erect leaves [6]. Leaf inclination1 (LC1) encodes an indole-3-acetate (IAA) amide synthetase OsGH3-1, whose functional gain mutant lc1-D exaggerated leaf angles due to increased cell elongation on the paraxial surface of the lamina joint [16]. Over-expression lines of auxin response factor 19 (OsARF19) in rice, shows an enlarged lamina inclination due to increased adaxial cell division [42]. These reports are similar to the OsPIN1b results, suggesting that they have a certain correlation in regulating lamina inclination through altering adaxial cell division.

OsPIN1b can be significantly induced by BR and IAA (Figure 6A). It is proven that phytohormone BR and IAA are the key reasons for OsPIN1b affecting leaf inclination. Furthermore, we analyzed the expression of BR or IAA biosynthesis and signal transduction-related genes in each transgenic line of OsPIN1b, and found that the expression of these genes was significantly inhibited in the mutants, but induced in the OsPIN1b overexpressing line, which was consistent with the insensitive response of ospin1b to BR and auxin (Figure 6B and Figure 7A–F). This is similar to the previous research that the BR signal transduction receptor BRI1 positively regulates the leaf inclination of rice, and the leaf inclination increases in the overexpression line of auxin response factor OsARF19 [4,42]. In addition, previous studies found that auxin stimulates the response of BR by increasing the levels of the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 [11]. OsARF19 increases leaf inclination by positive regulation of OsGH3-5 and OsBRI1 [42]. Aiming at regulation of leaf inclination, OsARF4 (auxin response factor 4) plays a role between auxin and BR signaling pathways [56]. In this study, 24-eBL greatly promoted the leaf inclination, while IAA slightly enlarged the leaf inclination with the increase in their concentration (Figure 7A–F). BR induced much higher leaf inclination than IAA, and a synergistic effect was observed between BR and IAA, which accords with our results [12,43]. These results prove that crosstalk occurs between auxin and BR during OsPIN1b, regulating lamina joint development and leaf inclination.

3.3. ospin1b Reduced the Plant Height and Leaf Inclination and Formed the Ideal Plant Architecture

Rice is one of the most important food crops, feeding more than half of the world’s population. With the steady growth of population, human demand for rice will increase rapidly, which requires the cultivation of excellent rice varieties with ideal plant configuration. Just as the first “green revolution”, the grain yield was significantly improved by planting lodging-resistant wheat and rice semi-dwarf varieties [57]. Thus, crop plants with desirable architecture, such as lodging-resistant semi-dwarf varieties are able to produce much higher grain yields. Leaf angle is one of the most important plant architecture parameters affecting light interception, photosynthetic efficiency, and planting density [1,2]. Our research found that ospin1b lines reduced leaf inclination (Figure 1C,D and Figure 5A,B) and decreased plant height (Figure S4), which is similar to the optimized architecture of rice. Thus, our study provides a novel perspective on the mechanism that auxin regulates the leaf inclination.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Rice seeds of wild-type, mutant, and transgenic lines were submerged (soaked) in water for 3 days in darkness of 37 °C, then the most uniformly germinated seeds were scattered on a floating net. Rice seedlings were cultured in nutrient solution (pH 5.5) [58] and grown under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle in a greenhouse of chamber at 28 °C/22 °C for 30 days.

For exogenous phytohormone treatments of OsPIN1b expression, 7-day-old WT/NIP rice seedlings were treated with different exogenous phytohormone (10 μM of IAA, 10 μM of 24-eBL, epibrassinolide). For the sensitivity test of BR, the WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OsPIN1b-overexpression lines were cultured in nutrient solution (pH 5.5) supplemented with 0.01, 0.1, 1 µM 24-eBL for 7 days in a greenhouse at 26 °C for 24 h dark per day, respectively. The length of root and coleoptile per line was measured and photographed.

4.2. Construction and Identification of ospin1b Mutants

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing technology was used to obtain ospin1b mutant lines. Cas9/gRNA target site selection and vector construction were conducted according to previous reports [59]. The OsPIN1b-pRGEB32 vector was introduced into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 and transformed into WT/NIP calli, as described previously [60]. Homozygous ospin1b mutants were screened by PCR analysis of the Cas9 label and DNA sequencing of the OsPIN1b specific editing site. The primer sequences used for plasmid construction and mutant identification are listed in Table S1.

4.3. Construction and Transformation of Binary Vectors

The open reading frame of OsPIN1b was amplified from the cDNA of WT/NIP, and the 2.6 kb promoter of the OsPIN1b was amplified from WT/NIP genomic DNA. 35S:OsPIN1b-sGFP and ProOsPIN1b:GUS vectors were constructed as described previously [25]. These vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 and transformed into WT/NIP calli. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

4.4. Subcellular Localization of OsPIN1b

The full-length coding region of OsPIN1b was inserted into a binary pCAMBIA1300 vector, which was labeled with synthetic green fluorescent protein (sGFP). The 35S:OsPIN1b-sGFP and plasma membrane marker pm-rbCD3-1008 were co-transfected into the Nicotiana bentamiana epidermal cells by Agrobacterium transformation and the isolated rice protoplasts by polyethylene glycol/calcium transfection and incubated overnight [61]. The fluorescent signals of the expressed proteins were observed by two-photon fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss LSM710; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), as described previously [24].

4.5. β- Glucuronidase (GUS) Staining

Each tissue (seeds germinated, 3 d; roots, 7 d; stems and leaves, 14 d; flowers, and 2 month of ProOsPIN1b:GUS transgenic rice were incubated in GUS staining buffer for 2 h at 37 °C, and then these tissues were soaked in 95% ethanol to remove chlorophyll and surface dye. Images of GUS-stained tissues were observed by stereomicroscope (Leica MZ95 microscope, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

4.6. RNA Extraction, RT-PCR, and Real-Time Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) Analyses

Total RNA was extracted from various tissues of rice WT/NIP seedlings, lamina joint of different periods, and different exogenous phytohormone-treated plants; seedlings of wild-type, ospin1b mutant, and OE-OsPIN1b by using the TIANGEN RNAprep pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer (NaNoDrop 1000; Thermo Scientific, United States). Total RNA (2 μg) was used to synthesize cDNA by using Hifair® Ⅱ1 st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (gDNA digester plus), and qRT-PCR was conducted using Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (No Rox) (Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) in a LightCycler® 480 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The cycle conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, one cycle; 95 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 20 s, 40 cycles; qRT-PCR was performed using three independent experiments with biological triplicates for each sample. OsACTIN (Os03g50885) was used as an internal control to calculate the fold change in expression. The primer sequences used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S2.

4.7. Exogenous Hormone Response Assay

Epibrassinolide (24-eBL, designated as BL; Solarbio Science and Technology, Beijing, China) was dissolved in DMSO, and indoleacetic acid (IAA; Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) was in ethanol, to proper concentrations as storage solutions. For the hormone treatments of leaf inclination, WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants, and OsPIN1b-overexpression lines were cultured in darkness for 7 days in a exogenous hormone-free nutrient solution, and then the lamina joints were cut with a length of about 3 cm and soaked in ddH2O containing 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 µM 24-eBL (0, 1, 10, and 100 µM IAA; 0 + 0, 0.01 + 1, 0.1 + 10, and 1 + 100 µM 24-eBL + IAA) for 3 days under same conditions, respectively. The leaf inclination in each group was measured and photographed. All experiments were independently repeated three times.

4.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Scanning electron microscopy was performed as described previously [44]. About 1 cm lamina joints of flag leaf of a two-month plant were excised from WT/NIP, ospin1b mutants and overexpression lines of rice. Samples were observed with an S-3000N scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

4.9. Endogenous IAA Contents Analysis by HPLC

The lamina joints (about 1 cm in length, 100 mg) of 7-day-old seedlings were ground to powder in liquid nitrogen. Extracting IAA and measuring its content refer to the previous research [62] using a Rigol L3000 high-performance liquid chromatograph with a C18 reversed-phase chromatographic column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). These Samples were analyzed by HPLC-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry at Suzhou Keming Biotechnology Company (Suzhou, China).

4.10. Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the NCBI Database or Rice Genome Annotation Project under the following accession numbers: OsPIN1b, LOC_Os02g50960; OsBRI1, LOC_Os01g52050; D2, LOC_Os01g10040; D11, LOC_Os04g39430; OsARF19, LOC_Os06g48950; OsIAA1, LOC_Os01g08320; and OsACTIN, LOC_Os03g50885.

4.11. Primer Sequences

The primers used are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhenyu Gao of China National Rice Research Institute for field production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants12020409/s1, Figure S1: Construction of ospin1b mutants via CRISPR-Cas9 system; Figure S2: Structure analysis of OsPIN1b protein; Figure S3: Sensitivity test of BR; Table S1: Primers Used for Vector Construction; Table S2: Primers Used for qRT-PCR Analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Q.; data curation, Y.Q., Y.Z. and S.H.; funding acquisition, Y.Q.; investigation, Y.Z., S.H., Y.L. (Yuqing Lin), J.Q., N.H., Y.L. (Yanyan Li), Y.F. and D.L.; methodology, Y.Z., S.H. and Y.L. (Yuqing Lin); project administration, Y.Q.; resources, Y.Q., Y.L. (Yuqing Lin) and J.Q.; software, Y.Z., S.H. and J.Q.; supervision, Y.L. (Yanyan Li), Y.F. and N.H.; visualization, J.Q. and Y.L. (Yuqing Lin); validation, formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation, Y.Q., Y.Z., S.H. and Y.L. (Yuqing Lin); writing review and editing, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its Supplementary materials published online. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number (s) can be found in the article/Supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060451), Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2022ZD11) and Applied Technology Research and Development Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2021PT0001) to Y.Q., and the Central Government Guiding Special Funds for the Development of Local Science and Technology (NO. 2020ZY0005) to D.L.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Sinclair T.R., Sheehy J.E. Erect Leaves and Photosynthesis in Rice. Science. 1999;283:1456–1457. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1455c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakamoto T., Morinaka Y., Ohnishi T., Sunohara H., Fujioka S., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Mizutani M., Sakata K., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., et al. Erect leaves caused by brassinosteroid deficiency increase biomass production and grain yield in rice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nbt1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan K., Li L., Hu P., Xu S.P., Xu Z.H., Xue H.W. A brassinolide-suppressed rice MADS-box transcription factor, OsMDP1, has a negative regulatory role in BR signaling. Plant J. 2006;47:519–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamuro C., Ihara Y., Xiong W., Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Ashikari M., Matsuoka K.M. Loss of Function of a Rice brassinosteroid insensitive1 Homolog Prevents Internode Elongation and Bending of the Lamina Joint. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1591–1605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L.Y., Bai M.Y., Wu J., Zhu J.Y., Wang H., Zhang Z., Wang W., Sun Y., Zhao J., Sun X., et al. Antagonistic HLH/bHLH transcription factors mediate brassinosteroid regulation of cell elongation and plant development in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3767–3780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun S., Chen D., Li X., Qiao S., Shi C., Li C., Shen H., Wang X. Brassinosteroid Signaling Regulates Leaf Erectness in Oryza sativa via the Control of a Specific U-Type Cyclin and Cell Proliferation. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Shimizu-Sato S., Inukai Y., Fujioka S., Shimada Y., Takatsuto S., Agetsuma M., Yoshida S., Watanabe Y., et al. Loss-of-function of a rice brassinosteroid biosynthetic enzyme, C-6 oxidase, prevents the organized arrangement and polar elongation of cells in the leaves and stem. Plant J. 2002;32:495–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong Z., Ueguchi-Tanaka M., Umemura K., Uozu S., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Ashikari M., Kitano H., Matsuoka M. A rice brassinosteroid-deficient mutant, ebisu dwarf (d2), is caused by a loss of function of a new member of cytochrome P450. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2900–2910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai M.Y., Zhang L.Y., Gampala S.S., Zhu S.W., Song W.Y., Chong K., Wang Z.Y. Functions of OsBZR1 and 14-3-3 proteins in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:13839–13844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706386104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng H., Hao M., Wang W., Mei D., Rachel W., Jia L., Wang H., Sang S., Tang M., Zhou R. Integrative RNA- and miRNA-Profile Analysis Reveals a Likely Role of BR and Auxin Signaling in Branch Angle Regulation of B. napus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:887. doi: 10.3390/ijms18050887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakamoto T., Morinaka Y., Inukai Y., Kitano H., Fujioka S. Auxin signal transcription factor regulates expression of the brassinosteroid receptor gene in rice. Plant J. 2013;73:676–688. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada K., Marumo S., Ikekawa N., Morisaki M., Mori K. Brassinolide and Homobrassinolide Promotion of Lamina Inclination of Rice Seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:323–325. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bian H., Xie Y., Guo F., Ning H., Zhu M. Distinctive expression patterns and roles of the miRNA393/TIR1 homolog module in regulating flag leaf inclination and primary and crown root growth in rice (Oryza sativa) N. Phytol. 2012;196:149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Y., You J., Xiong L. Characterization of OsIAA1 gene, a member of rice Aux/IAA family involved in auxin and brassinosteroid hormone responses and plant morphogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:297–309. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9474-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S.W., Li C.H., Cao J., Zhang Y.C., Zhang S.Q., Xia Y.F., Sun D.Y., Sun Y. Altered Architecture and Enhanced Drought Tolerance in Rice via the Down-Regulation of Indole-3-Acetic Acid by TLD1/OsGH3.13 Activation. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1889–1901. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.146803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao S.Q., Xiang J.J., Xue H.W. Studies on the Rice LEAF INCLINATION1 (LC1), an IAA–amido Synthetase, Reveal the Effects of Auxin in Leaf Inclination Control. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:174–187. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X., Yang C.Y., Miao R., Zhou C.L., Cao P.H., Lan J., Zhu X.J., Mou C.L., Huang Y.S., Liu S.J. DS1/OsEMF1 interacts with OsARF11 to control rice architecture by regulation of brassinosteroid signaling. Rice. 2018;11:46. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0239-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang G., Hu H., van de Meene A., Zhang J., Dong L., Zheng S., Zhang F., Betts N.S., Liang W., Bennett M.J., et al. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS 6 and 17 control the flag leaf angle in rice by regulating secondary cell wall biosynthesis of lamina joints. Plant Cell. 2021;33:3120–3133. doi: 10.1093/plcell/koab175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshikawa T., Ito M., Sumikura T., Nakayama A., Itoh J.C. The rice FISH BONE gene encodes a tryptophan aminotransferase, which affects pleiotropic auxin-related processes. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014;78:927–936. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adamowski M., Friml J. PIN-Dependent Auxin Transport: Action, Regulation, and Evolution. Plant Cell. 2015;27:20–32. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.134874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geisler M., Blakeslee J.J., Bouchard R., Lee O.R., Vincenzetti V., Bandyopadhyay A., Titapiwatanakun B., Peer W.A., Bailly A., Richards E.L., et al. Cellular efflux of auxin catalyzed by the Arabidopsis MDR/PGP transporter AtPGP1. Plant J. 2005;44:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisler M., Murphy A.S. The ABC of auxin transport: The role of p-glycoproteins in plant development. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swarup R., Péret B. AUX/LAX family of auxin influx carriers—An overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:225. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M., Qiao J.Y., Yu C.L., Chen H., Sun C.D., Huang L.Z., Li C.Y., Geisler M., Qian Q., Jiang D.A., et al. The auxin influx carrier, OsAUX3, regulates rice root development and responses to aluminium stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:1125–1138. doi: 10.1111/pce.13478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu C.L., Sun C.D., Shen C., Wang S., Liu F., Liu Y., Chen Y.L., Li C., Qian Q., Aryal B. The auxin transporter, OsAUX1, is involved in primary root and root hair elongation and in Cd stress responses in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant J. 2015;83:818–830. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiśniewska J., Xu J., Seifertová D., Brewer P.B., Růžička K., Blilou I., Rouquié D., Benková E., Scheres B., Friml J. Polar PIN Localization Directs Auxin Flow in Plants. Science. 2006;312:883. doi: 10.1126/science.1121356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blilou I., Xu J., Wildwater M., Willemsen V., Paponov I., Friml J., Heidstra R., Aida M., Palme K., Scheres B. The PIN auxin efflux facilitator network controls growth and patterning in Arabidopsis roots. Nature. 2005;433:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature03184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friml J., Vieten A., Sauer M., Weijers D., Schwarz H., Hamann T., Offringa R., Juergens G. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2003;426:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature02085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gälweiler L., Guan C., M-Ller A., Wisman E., Mendgen K., Yephremov A., Palme K. Regulation of Polar Auxin Transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis Vascular Tissue. Science. 1998;282:2226–2230. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada K., Ueda J., Komaki M.K., Shimura B.Y. Requirement of the Auxin Polar Transport System in Early Stages of Arabidopsis Floral Bud Formation. Plant Cell. 1991;3:677–684. doi: 10.2307/3869249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J.R., Hu H., Wang G.H., Jing L., Chen J.Y., Ping W. Expression of PIN genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Tissue specificity and regulation by hormones. Mol. Plant. 2009;2:823–831. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun H., Tao J., Bi Y., Hou M., Lou J., Chen X., Zhang X., Le L., Xie X., Koichi Y. OsPIN1b is Involved in Rice Seminal Root Elongation by Regulating Root Apical Meristem Activity in Response to Low Nitrogen and Phosphate. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:13014. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29784-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu M., Zhu L., Shou H., Wu P. A PIN1 Family Gene, OsPIN1, involved in Auxin-dependent Adventitious Root Emergence and Tillering in Rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:1674–1681. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y., Fan X., Song W., Zhang Y., Xu G. Over-expression of OsPIN2 leads to increased tiller numbers, angle and shorter plant height through suppression of OsLAZY1. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012;10:139–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu G., Coneva V., Casaretto J.A., Ying S., Mahmood K., Liu F., Nambara E., Bi Y.M., Rothstein S.J. OsPIN5b modulates rice (Oryza sativa) plant architecture and yield by changing auxin homeostasis, transport and distribution. Plant J. 2015;83:913–925. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng Y., Wen J., Zhao W., Wang Q., Huang W. Rational Improvement of Rice Yield and Cold Tolerance by Editing the Three Genes OsPIN5b, GS3, and OsMYB30 With the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;10:1663. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hou M., Luo F., Wu D., Zhang X., Zhang Y. OsPIN9, an auxin efflux carrier, is required for the regulation of rice tiller bud outgrowth by ammonium. N. Phytol. 2020;229:935–949. doi: 10.1111/nph.16901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyashita Y., Takasugi T., Ito Y. Identification and expression analysis of PIN genes in rice. Plant Sci. 2010;178:424–428. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Q., Li J., Zhang W., Yan S., Wang R., Zhao J., Li Y., Qi Z., Sun Z., Zhu Z. The putative auxin efflux carrier OsPIN3t is involved in the drought stress response and drought tolerance. Plant J. 2012;72:805–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paponov I.A., Teale W.D., Trebar M., Blilou I., Palme K. The PIN auxin efflux facilitators: Evolutionary and functional perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson B.K., Cai X., Nebenführ A. A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 2007;51:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S., Wang S., Xu Y., Yu C., Shen C., Qian Q., Geisler M., Jiang D.A., Qi Y. The auxin response factor, OsARF19, controls rice leaf angles through positively regulating OsGH3-5 and OsBRI1. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:638–654. doi: 10.1111/pce.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao H., Chen S. Brassinosteroid-induced rice lamina joint inclination and its relation to indole-3-acetic acid and ethylene. Plant Growth Regul. 1995;16:189–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00029540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao S.Q., Hu J., Guo L.B., Qian Q., Xue H.W. Rice leaf inclination2, a VIN3-like protein, regulates leaf angle through modulating cell division of the collar. Cell Res. 2010;20:935–947. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Z., Wang Z.Y., Li J., Zhu Q., Lamb C., Ronald P., Chory J. Perception of brassinosteroids by the extracellular domain of the receptor kinase BRI1. Science. 2000;288:2360–2363. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinoshita T., Caño-Delgado A., Seto H., Hiranuma S., Fujioka S., Yoshida S., Chory J. Binding of brassinosteroids to the extracellular domain of plant receptor kinase BRI1. Nature. 2005;433:167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature03227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J., Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z.Y., Seto H., Fujioka S., Yoshida S., Chory J. BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature. 2001;410:380–383. doi: 10.1038/35066597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao J., Wu C., Yuan S., Yin L., Sun W., Zhao Q., Zhao B., Li X. Kinase activity of OsBRI1 is essential for brassinosteroids to regulate rice growth and development. Plant Sci. 2013;199–200:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanabe S., Ashikari M., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., Yano M., Yoshimura A., Kitano H., Matsuoka M., Fujisawa Y., et al. A novel cytochrome P450 is implicated in brassinosteroid biosynthesis via the characterization of a rice dwarf mutant, dwarf11, with reduced seed length. Plant Cell. 2005;17:776–790. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu X., Wang H., Leung D.W.M., He Z., Zhang J., Peng X., Liu E. Overexpression of OsIAAGLU reveals a role for IAA–glucose conjugation in modulating rice plant architecture. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:731–739. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gallavotti A. The role of auxin in shaping shoot architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:2593–2608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McSteen P. Auxin and Monocot Development. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a001479. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Petrasek J., Friml J. Auxin transport routes in plant development. Development. 2009;136:2675–2688. doi: 10.1242/dev.030353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Z., Gao L., Ke M., Gao Z., Tu T., Huang L., Chen J., Guan Y., Huang X., Chen X. GmPIN1-mediated auxin asymmetry regulates leaf petiole angle and plant architecture in soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022;64:1325–1338. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiao J., Zhang Y., Han S., Chang S., Gao Z., Qi Y., Qian Q. OsARF4 regulates leaf inclination via auxin and brassinosteroid pathways in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13:979033. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.979033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khush G.S. Green revolution: Preparing for the 21st century. Genome. 1999;42:646–655. doi: 10.1139/g99-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S.K., Zhang S.N., Sun C.D., Xu Y.X., Chen Y., Yu C.L., Qian Q., Jiang D.A., Qi Y.H. Auxin response factor (OsARF12), a novel regulator for phosphate homeostasis in rice (Oryza sativa) N. Phytol. 2013;201:91–103. doi: 10.1111/nph.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xie K., Minkenberg B., Yang Y. Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420294112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hiei Y., Ohta S., Komari T., Kumashiro T. Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J. 1994;6:271–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.6020271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qi Y., Wang S., Shen C., Zhang S., Chen Y., Xu Y., Liu Y., Wu Y., Jiang D. OsARF12, a transcription activator on auxin response gene, regulates root elongation and affects iron accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa) N. Phytol. 2012;193:109–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shao Y., Zhou H.Z., Wu Y., Zhang H., Lin J., Jiang X., He Q., Zhu J., Li Y., Yu H. OsSPL3, an SBP-Domain Protein, Regulates Crown Root Development in Rice. Plant Cell. 2019;31:1257–1275. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its Supplementary materials published online. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number (s) can be found in the article/Supplementary materials.