ABSTRACT

Background

While American nephrology societies recommend using the 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) equation without a Black race coefficient, it is unknown how this would impact disease distribution, prognosis and kidney failure risk prediction in predominantly White non-US populations.

Methods

We studied 1.6 million Stockholm adults with serum/plasma creatinine measurements between 2007 and 2019. We calculated changes in eGFR and reclassification across KDIGO GFR categories when changing from the 2009 to 2021 CKD-EPI equation; estimated associations between eGFR and the clinical outcomes kidney failure with replacement therapy (KFRT), (cardiovascular) mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events using Cox regression; and investigated prognostic accuracy (discrimination and calibration) of both equations within the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

Results

Compared with the 2009 equation, the 2021 equation yielded a higher eGFR by a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 3.9 (2.9–4.8) mL/min/1.73 m2, which was larger at older age and for men. Consequently, 9.9% of the total population and 36.2% of the population with CKD G3a–G5 was reclassified to a higher eGFR category. Reclassified individuals exhibited a lower risk of KFRT, but higher risks of all-cause/cardiovascular death and major adverse cardiovascular events, compared with non-reclassified participants of similar eGFR. eGFR by both equations strongly predicted study outcomes, with equal discrimination and calibration for the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

Conclusions

Implementing the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in predominantly White European populations would raise eGFR by a modest amount (larger at older age and in men) and shift a major proportion of CKD patients to a higher eGFR category. eGFR by both equations strongly predicted outcomes.

Keywords: CKD-EPI, creatinine, epidemiology, glomerular filtration rate, kidney diseases

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What is already known about this subject?

The Task Force of the US National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology has recommended immediate implementation of the new 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation in all laboratories in the USA. Implementation of this equation may be considered both for use in clinical practice and in research worldwide.

The 2021 CKD-EPI equation has larger bias compared with measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) than the 2009 equation for non-Black individuals (–3.9 vs –0.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively), and many European countries still have predominantly White populations with low ethnic diversity or have been traditionally using the non-Black race coefficient in automatic estimated GFR (eGFR) reporting or research.

The practical implications of changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation on disease distribution, prognosis and kidney failure risk prediction in European settings are unknown.

What this study adds?

In a cohort of 1.6 million individuals with creatinine testing in Stockholm, we found that changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation would decrease the prevalence of CKD G3a–G5 from 5.1% to 3.8%, and reclassify 36.2% of people with CKD G3a–G5 to a higher eGFR category.

Reclassified individuals were older and therefore exhibited higher crude risks of all-cause/cardiovascular death and major adverse cardiovascular events, and lower risk of kidney failure with replacement therapy.

eGFR by both equations strongly predicted kidney, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes, and both equations had similar prediction performance in the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

On a population level, changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation will decrease the estimated prevalence of CKD G3a–G5 in White European populations, with the largest decreases among the elderly.

On an individual level, the substantial reclassification to higher eGFR categories may have important implications for medication initiation, discontinuation and dosing, and may lead to later nephrologist referral, planning for dialysis and evaluation for kidney transplantation in White European populations.

INTRODUCTION

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is widely used for the detection, diagnosis, prognosis and management of patients with kidney diseases [1–3]. GFR thresholds are a major underpinning of many clinical decisions in medicine: amongst others, they guide medication initiation, discontinuation and dosing; nephrologist referral, planning for dialysis and evaluation of kidney transplantation; utilization of contrast-based tests and procedures, such as computed tomography scans with intravascular contrast or cardiac catheterization; clinical trial eligibility and recruitment; and on a population level are used for surveillance and population tracking of kidney diseases [4–7].

The creatinine equation currently recommended by the international Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline is the 2009 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation [1], and it estimates GFR based on the variables age, sex, race (Black vs non-Black) and creatinine. However, unlike age and sex, race is considered a social, not a biological construct [8], and its inclusion has been challenged recently [8–15]. A new creatinine-based eGFR equation that does not include a race coefficient was therefore developed by CKD-EPI in 2021, including refitted coefficients for age, sex and creatinine [16].

The Task Force of the US National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology has recommended immediate implementation of the new 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation in all laboratories in the USA [17], and implementation of this equation may be considered both for use in clinical practice and in research worldwide. The 2021 CKD-EPI equation has larger bias compared with measured GFR than the 2009 equation for non-Black individuals (–3.9 vs –0.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively) [16], and in Europe, many countries still have predominantly White populations with low ethnic diversity and have been traditionally using non-Black race coefficient in automatic eGFR reporting or research [18–22].

In this study, we set out to evaluate how transitioning from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation would affect disease distribution and prognostic accuracy in non-US settings. Using a large Swedish population of predominantly White participants accessing routine healthcare we assessed (i) reclassification across KDIGO GFR categories when changing from the 2009 to 2021 CKD-EPI equation; (ii) associations between eGFR and kidney failure with replacement therapy (KFRT), (cardiovascular) mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events; and (iii) prognostic accuracy of both eGFR equations within the widely used predictive model for kidney failure, the Kidney Failure Risk Equation. We note that this study is not about the abilities of the 2009 and 2021 CKD-EPI equation to predict measured GFR, which has already been investigated [16]; instead, we focus on the practical implications of using one or the other equation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

The study population consisted of participants included in the Stockholm Creatinine Measurements (SCREAM) project, a healthcare utilization cohort including all adult residents from the region of Stockholm, Sweden between 2006 and 2019 [23]. There is a sole healthcare provider in Stockholm region, which provides universal and tax-funded healthcare to 20%–25% of Sweden's population. In brief, SCREAM is a repository of laboratory tests from any resident of the Stockholm region that was linked, via each resident's unique personal identification number, to regional and national administrative databases with complete information on demographics, healthcare use, dispensed drugs, diagnoses and vital status, with virtually no loss to follow-up. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study.

Study population

We included all adult (≥18 years) participants who had at least one outpatient creatinine measurement between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2018 and no KFRT. The date of the first creatinine measurement fitting these criteria was the index date of the study. Patients were followed from index date to the first occurrence of a study outcome, death or end of follow-up (31 December 2019), whichever occurred first.

2009. and 2021 CKD-EPI eGFR equations

We calculated eGFR with the 2009 and 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equations, hereafter referred to as 2009 (original) and 2021 (new) equations [16, 24]. Creatinine was measured in plasma, with either an enzymatic or corrected Jaffe method (alkaline picrate reaction); both methods are traceable to isotope dilution mass spectroscopy standards. Creatinine tests from inpatient care, emergency room visits and taken within 24 h before or after hospital admission were excluded because they are less likely to represent steady kidney function. For the 2009 equation, eGFR was calculated using the non-Black coefficient. Race is not available in our cohort, because Sweden, to prevent discrimination, does not allow collecting data on ethnicity. Data on country of birth are collected and published by the government on an annual basis [25], and based on these population statistics, we estimated that ∼2.5% of the included cohort were born in African countries and assumed they may be of African ethnicity. These individuals were not excluded from the analyses.

Statistical analyses

Changes in eGFR with the 2021 vs 2009 equation

We calculated the eGFR distributions for the 2009 and 2021 equations separately using kernel density estimation. Since the coefficients of age, sex and creatinine differ between both equations, we investigated their influence on eGFR increase by calculating eGFR changes for each individual when changing from the 2009 to 2021 equation and plotting this change against age, sex and 2009 eGFR level. We also evaluated this in subgroups of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

To assess reclassification, we cross-tabulated eGFR categories with the 2009 and 2021 equations according to the KDIGO classification (≥90, 60–89, 45–59, 30–44, 15–29, <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, corresponding to GFR categories G1, G2, G3a, G3b, G4 and G5, respectively) and calculated the proportion of participants in each category of the 2009 equation that was reclassified by the 2021 equation. Analyses were repeated within subgroups of age, sex, hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

We compared characteristics of reclassified and non-reclassified individuals, including age, sex, attained education, comorbidities, medication use and calendar year, with definitions detailed in Supplementary Table S1. None of the included variables had missing values.

Association between eGFR and kidney, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes

We described the association between eGFR by both equations and the outcomes KFRT, all-cause death, cardiovascular death and major cardiovascular events (MACE) by fitting a cause-specific Cox model, modelling eGFR with a restricted cubic spline with five knots placed on the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th and 95th percentile of the data. An eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73 m2 was taken as reference value, similar to previous studies [26]. KFRT was defined as a composite of maintenance dialysis or kidney transplantation. MACE was defined as a composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal stroke. Definitions of study outcomes are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Cause-specific Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The date of the creatinine measurement was defined as the start of follow-up (T0). Patients were followed until the first occurrence of the study outcome, death, emigration or end of follow-up (31 December 2019), whichever occurred first. In the primary analysis, we present unadjusted hazard ratios, since our aim was to understand the prognostic value of the initial eGFR used for CKD staging. Furthermore, since the variables age and sex are included in the eGFR equations, the different weights of these variables in the 2009 and 2021 equations may explain differences in the magnitude of the association between eGFR and outcomes. Adjusting for age and sex could therefore potentially ‘hide’ the effects of these changes in coefficients on risk relationships. Harrell's C-index was calculated as a measure of discrimination, using a prediction horizon of 10 years. For the outcomes KFRT, cardiovascular death, and MACE, we accounted for the competing risk of (non-cardiovascular) death by setting the follow-up time to the administrative censoring time for patients who experienced the competing event [27]. In further analyses, we adjusted hazard ratios for age and sex, as well as comorbidities and medication use, to make results comparable with previous studies [26, 28].

We compared the risk of KFRT, all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and MACE between reclassified and non-reclassified individuals in the same eGFR category (e.g. we compared the risk of KFRT among those who were reclassified from G4 to G3b with those who remained in G4). Since reclassified individuals were closer to the GFR threshold than non-reclassified individuals, the reclassified had a higher mean eGFR than non-reclassified (Supplementary Fig. S1). To explore to what extent this eGFR difference explained the difference we observed in prognosis, a second analysis was performed in which we adjusted for 2009 eGFR level. Additionally, since the age coefficient became larger in the 2021 equation and age is a strong predictor for outcomes, we additionally adjusted for age in a third analysis. This analysis explored how much of the difference in prognosis in the second analysis was explained by age (Supplementary Fig. S1). We also calculated the category-based net reclassification index (NRI), with categories based on the KDIGO eGFR cutoffs (detailed explanations provided in Supplementary Methods) [29].

Prognostic accuracy of eGFR with the 2009 and 2021 equation for kidney failure risk prediction

We investigated discrimination and calibration abilities in the four-variable Kidney Failure Risk Equation (which uses age, sex, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio and eGFR), using the non-North American equations with a prediction horizon of 5 years [30]. Population selection and detailed explanations are supplied in Supplementary Methods. These analyses were performed in a separate cohort of individuals with available albuminuria measurements and an eGFR between 15 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and repeated among individuals with an eGFR between 15 and 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 [31].

RESULTS

We included a total of 1 601 237 participants who had at least one ambulatory creatinine measurement in Stockholm healthcare between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2018 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Mean age was 48 years, 53% were women and mean plasma creatinine was 74 μmol/L (Supplementary Table S3). The most common diagnosed comorbidities were hypertension (14%), diabetes (5%), and arrythmia (5%), and the most commonly used medications were non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (13%), renin-angiotensin system inhibition (RASi, 10%) and beta-blockers (10%). Participants with lower eGFR were more likely to be older, women, have more comorbid conditions, and use more medications (Supplementary Table S3). Similar results were observed across categories of eGFR with the 2009 equation (Supplementary Table S4).

Changes in eGFR with the 2021 vs 2009 equation

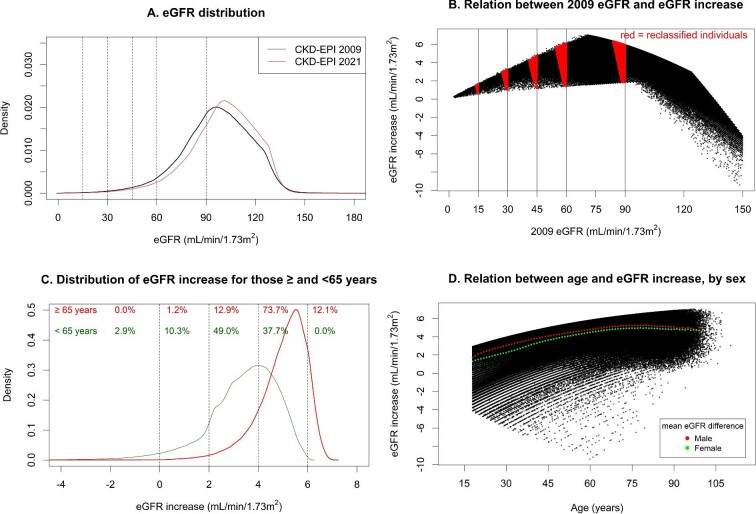

eGFR with the 2021 equation was higher than with the 2009 equation by a median of 3.9 (IQR 2.9–4.8) mL/min/1.73 m2 (Fig. 1A). All participants with an original eGFR level between 9 and 105 mL/min/1.73 m2 had higher values with the new equation, whereas participants with 2009 eGFR >105 mL/min/1.73 m2 could also have lower values (Fig. 1B). Changes in eGFR were smallest for individuals with an original eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 with greatest change for participants with an original eGFR around 70 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1:

(A) eGFR distributions for 2021 and 2009 CKD-EPI equations. (B) Relation between 2009 eGFR and increase in eGFR when changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation. (C) Distribution of eGFR increase when changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation, separately for those ≥65 and <65 years. (D) Relation between age and increase in eGFR when changing from the 2009 to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation, with mean increase shown separately for both sexes. (A) Distribution based on kernel density estimation. Dotted vertical lines depict KDIGO GFR thresholds. (B) Each black dot represents an individual. Vertical lines represent GFR thresholds. Red areas denote individuals who are reclassified to a less severe CKD G category. (C) Distribution based on kernel density estimation. Numbers depict the proportion of participants within categories of eGFR difference (<0, 0–2, 2–4, 4–6, >6 mL/min/1.73 m2), separately for those ≥65 and <65 years. (D) Each black dot represents an individual. The red and green dots show the mean difference in eGFR between the 2021 and 2009 equation for males and females, respectively, by 1-year age strata.

Older individuals had larger increases in eGFR than younger participants. For instance, 73.7% of participants older than 65 years had an increase between 4 and 6 mL/min/1.73 m2, compared with 37.7% of those younger than 65 years (Fig. 1C and D). Males also had a larger eGFR increase compared with females, independent of age (Fig. 1D). Shifts in eGFR distribution were consistent across subgroups of hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Supplementary Table S5 and Fig. S3).

Reclassification proportions

In total, 158 944 participants (9.9% of the cohort) were reclassified to higher eGFR categories with the 2021 equation, and no participants were reclassified to more severe eGFR categories (Table 1). For instance, 39.0% of individuals with an original eGFR between 45 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 were reclassified by the 2021 equation to an eGFR between 60 and 89 mL/min/1.73 m2. Among participants with CKD G3–G5 (N = 81 674), 29 581 participants (36.2%) were reclassified to a higher GFR category.

Table 1.

Reclassification across eGFR categories with the 2021 CKD-EPI equation from eGFR categories with the 2009 CKD-EPI equation

| eGFR category | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| with the 2009 | |||||||

| equation, mL/min/ | eGFR category with the 2021 equation, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ||||||

| 1.73 m2 | ≥90 | 60–89 | 45–59 | 30–44 | 15–29 | <15 | Total |

| ≥90 | 1 036 982 (100%) | 1 036 982 (64.8%) | |||||

| 60–89 | 129 363 (26.8%) | 353 218 (73.2%) | 482 581 (30.1%) | ||||

| 45–59 | 20 912 (39.0%) | 32 712 (61.0%) | 53 624 (3.3%) | ||||

| 30–44 | 6716 (33.1%) | 13 559 (66.9%) | 20 275 (1.3%) | ||||

| 15–29 | 1709 (27.0%) | 4623 (73.0%) | 6332 (0.4%) | ||||

| <15 | 244 (16.9%) | 1199 (83.1%) | 1443 (0.1%) | ||||

| Total | 1 166 345 (72.8%) | 374 130 (23.4%) | 39 428 (2.5%) | 15 268 (1.0%) | 4867 (0.3%) | 1199 (0.1%) | 1 601 237 |

Data in blue cells are the number of participants who are reclassified to less severe CKD G categories, and percentages represent the proportion of participants in the eGFR category with the 2009 equation that are reclassified to a higher eGFR category with the 2021 equation. The percentages in parentheses in the ‘Total’ row and column denote the proportion of participants in each eGFR category. Total number of participants reclassified = 158 944 (9.9% of total population). Total number of participants with CKD G3a–G5 reclassified = 29 581 (36.2% of CKD G3a–G5 population).

When applying the 2021 equation, the population prevalence of CKD G3a–G5 decreased from 5.1% to 3.8% (Supplementary Table S5). Likewise, CKD G3b–G5 prevalence decreased from 1.8% to 1.3%, and CKD G4–G5 prevalence decreased from 0.5% to 0.4%. Decreases in CKD prevalence were observed across all subgroups of age, sex and presence/absence of hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Supplementary Table S5). The absolute decrease in prevalence of CKD G3a–G5 was highest in participants ≥65 years (from 21.9% to 16.5%), those with diabetes (from 16.7% to 13.4%) and those with cardiovascular disease (from 23.3% to 18.6%).

Older adults were more likely to be reclassified than younger ones: while 19.7% of participants ≥65 years with CKD G5 were reclassified from CKD G5 to G4, only 10.9% of participants <65 years did so. A similar pattern was observed for reclassification from G4 to G3b and from G3b to G3a (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). In general, reclassification proportions across GFR categories were similar for females and males, individuals with and without hypertension, with and without diabetes, and with and without cardiovascular disease (Supplementary Tables S8–S15).

Characteristics and outcomes of reclassified vs non-reclassified individuals

Table 2 describes general characteristics of reclassified versus non-reclassified participants in the total cohort and for those with CKD G3–G5 with the 2009 equation. In the total cohort, reclassified individuals were older, had a higher proportion of men, more comorbidities and used more medications. Furthermore, they had eGFR values closer to the GFR category thresholds than non-reclassified participants (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Tables S16 and S17). Conversely, among those with CKD G3–G5 with the 2009 equation, reclassified individuals had similar age compared with non-reclassified, a higher eGFR, and lower presence of comorbidities and medication use.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of reclassified and non-reclassified individuals when changing from the 2009 to 2021 equation

| All individuals (N = 1 601 237) | Individuals with CKD G3–5 with the 2009 equation (N = 81 674) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Reclassified to a higher eGFR category (N = 158 944) | Not reclassified (N = 1 442 293) | Reclassified to a higher eGFR category (N = 29 581) | Not reclassified (N = 52 093) |

| Mean age (SD), years | 62 (16) | 46 (18) | 77 (12) | 77 (13) |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| <50 years | 37 454 (24) | 869 312 (60) | 860 (3) | 2368 (5) |

| 50–59 years | 27 576 (17) | 223 430 (15) | 1669 (6) | 2666 (5) |

| 60–69 years | 39 668 (25) | 184 989 (13) | 4614 (16) | 6872 (13) |

| 70–79 years | 36 647 (23) | 88 856 (6) | 8553 (29) | 13 305 (26) |

| ≥80 years | 17 599 (11) | 75 706 (5) | 13 885 (47) | 26 882 (52) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 80 067 (50) | 774 139 (54) | 17 435 (59) | 31 264 (60) |

| Mean plasma creatinine (SD), μmol/La | 80 (21) | 73 (23) | 104 (30) | 130 (75) |

| eGFR with the 2009 equation, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 81 (14) | 98 (21) | 53 (9) | 44 (11) |

| eGFR with the 2021 equation, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 86 (15) | 102 (20) | 57 (10) | 47 (12) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| Compulsory school | 33 973 (22) | 228 433 (16) | 10 370 (37) | 19 427 (39) |

| Secondary school | 60 681 (39) | 553 645 (39) | 10 759 (38) | 18 898 (38) |

| University | 60 535 (39) | 633 786 (45) | 7009 (25) | 10 875 (22) |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 40 768 (26) | 187 345 (13) | 14 342 (48) | 27 650 (53) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5943 (4) | 24 795 (2) | 2817 (10) | 6065 (12) |

| Other ischemic heart disease | 12 595 (8) | 50 921 (4) | 5750 (19) | 11 777 (23) |

| Heart failure | 8083 (5) | 31 153 (2) | 5284 (18) | 12 268 (24) |

| Stroke | 6906 (4) | 28 571 (2) | 3251 (11) | 6673 (13) |

| Other cerebrovascular disease | 6079 (4) | 25 305 (2) | 2854 (10) | 5868 (11) |

| Arrhythmia | 13 442 (8) | 61 567 (4) | 6194 (21) | 12 447 (24) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3172 (2) | 14 073 (1) | 1568 (5) | 3473 (7) |

| Diabetes | 13 059 (8) | 72 208 (5) | 4620 (16) | 9656 (19) |

| Cancer | 6920 (4) | 33 063 (2) | 2150 (7) | 4096 (8) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5417 (3) | 22 690 (2) | 1904 (6) | 3814 (7) |

| Liver disease | 2006 (1) | 18 490 (1) | 471 (2) | 954 (2) |

| Concomitant medications, n (%) | ||||

| Beta blocker | 28 809 (18) | 132 472 (9) | 10 860 (37) | 21 400 (41) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 14 842 (9) | 65 105 (5) | 5138 (17) | 10 135 (19) |

| Diuretic | 21 212 (13) | 88 947 (6) | 10 950 (37) | 23 737 (46) |

| RASi | 27 599 (17) | 127 590 (9) | 9642 (33) | 19 603 (38) |

| Lipid-lowering drug | 21 924 (14) | 95 617 (7) | 6722 (23) | 12 717 (24) |

| NSAIDs | 22 259 (14) | 178 010 (12) | 4101 (14) | 7090 (14) |

| Calendar year, n (%) | ||||

| 2007–10 | 115 430 (73) | 882 148 (61) | 25 694 (87) | 45 943 (88) |

| 2011–14 | 25 314 (16) | 321 304 (22) | 2278 (8) | 3546 (7) |

| 2015–19 | 18 200 (11) | 238 841 (17) | 1609 (5) | 2604 (5) |

n = number; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; RASi = renin-angiotensin system inhibition (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker); NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Mean (SD) plasma creatinine is 0.90 (0.24) mg/dL for reclassified and 0.83 (0.26) mg/dL for non-reclassified individuals. To convert plasma creatinine from μmol/L to mg/dL, multiply by 0.0113.

When comparing participants within each KDIGO GFR category, we observed a lower risk for the reclassified vs non-reclassified for KFRT, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MACE (Supplementary Table S18A). However, reclassified participants had a higher eGFR than non-reclassified because they were closer to the upper GFR threshold of their 2009 G category (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table S16). After adjusting for differences in eGFR, reclassified participants had a lower risk for KFRT than non-reclassified ones, but higher risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MACE (Supplementary Table S18B). For instance, participants with an eGFR between 30 and 44 mL/min/1.73 m2 with the 2009 equation who were reclassified had a hazard ratio of 0.62 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42–0.92] for KFRT, 1.23 (1.17–1.30) for all-cause mortality, 1.30 (1.21–1.40) for cardiovascular mortality and 1.25 (1.17–1.33) for MACE, compared with non-reclassified participants. Differences in outcomes between these two groups were largely explained by the older age of the reclassified: after additional adjustment for age the hazard ratios became 0.91 (0.66–1.24) for KFRT, 1.07 (1.01–1.12) for all-cause mortality, 1.11 (1.03–1.19) for cardiovascular mortality and 1.09 (1.01–1.16) for MACE (Supplementary Table S18C). For KFRT, the event NRI was –11.6% (95% CI –12.8 to –10.2) and the non-event NRI was 9.9% (95% CI 9.9–10.0), meaning that 11.6% of patients who experienced KFRT were ‘inappropriately’ classified to a lower-risk KDIGO category, whereas 9.9% of patients who did not experience KFRT were ‘appropriately’ classified to a lower-risk KDIGO category. Event and non-event NRI were –18.3% (–18.5 to –18.1) and 8.7% (8.6–8.7) for all-cause mortality, –19.0% (–19.3 to –18.7) and 9.5% (9.5–9.6) for cardiovascular death and −18.1% (–18.3 to –17.9) and 9.2% (9.1–9.2) for MACE, respectively. NRI across subgroups are shown in Supplementary Table S19.

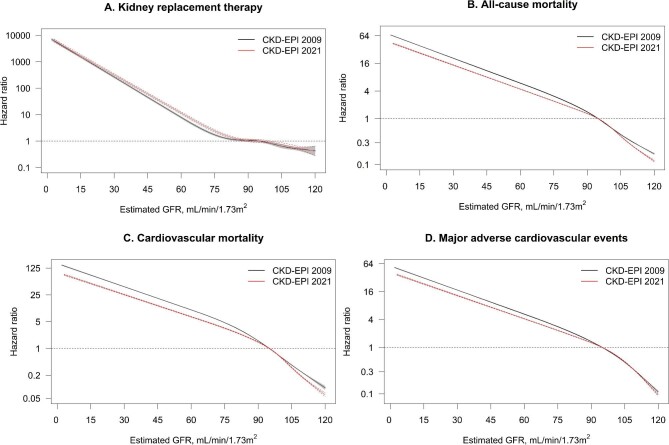

Association between eGFR and kidney, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes

During a median of 9.5 (IQR 5.6–11.9) years of follow-up (corresponding to a total of 13 731 737 person years), 194 247 participants died, of which 65 162 due to cardiovascular causes; 124 210 experienced MACE and 2533 started KFRT. eGFR with the 2021 and 2009 equations was strongly associated with these outcomes: compared with an eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73 m2, the hazard ratios for KFRT were 1690.5 (95% CI 1519.4–1880.9) for an eGFR of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 with the 2021 equation and 1528.6 (1373.8–1700.8) for an eGFR of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 with the 2009 equation (Fig. 2). Similarly, the hazard ratios were 27.0 (26.4–27.5) and 38.8 (38.1–39.5) for all-cause mortality, 49.4 (47.9–51.0) and 81.8 (79.3–84.4) for cardiovascular mortality, and 23.5 (22.9–24.1) and 31.5 (30.8–32.3) for MACE, for eGFR of 15 vs 95 mL/min/1.73 m2 with the 2021 equation and 2009 equation, respectively. Similar findings were observed among subgroups of age, when adjusting for age and sex (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5), and when additionally adjusting for comorbidities and medication use (Supplementary Fig. S6). When adjusting for covariates, the relationships between eGFR and all-cause/cardiovascular mortality and MACE became U-shaped instead of linear on the log scale, and hazard ratios were attenuated.

FIGURE 2:

Hazard ratios for the association between eGFR with the 2021 and 2009 CKD-EPI equation and kidney failure with replacement therapy (A), all-cause mortality (B), cardiovascular mortality (C) and major adverse cardiovascular events (D). An eGFR of 95 mL/min/1.73 m2 was taken as reference value. Dotted red lines depict 95% confidence intervals for the 2021 equation, and shaded grey areas depict 95% confidence intervals for the 2009 equation. eGFR was modelled as a restricted cubic spline with five knots at the 5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th and 95th percentile. Note that Y-axis is on a log-scale.

Prognostic accuracy of eGFR with the 2009 and 2021 equation for kidney failure risk prediction

Discrimination and calibration of the Kidney Failure Risk Equation was assessed among participants with available albuminuria measurements and an eGFR between 15 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and baseline characteristics of this subcohort are shown in Supplementary Table S21. Discrimination for the Kidney Failure Risk Equation was identical when using the 2021 or 2009 equations, with a C-statistic of 0.914 (95% CI 0.905–0.923) (Supplementary Table S22). Calibration of predicted versus observed risk showed that both models substantially overestimated the risk of kidney failure (Supplementary Fig. S7A, Table S23). Upon visual inspection, overprediction was slightly lower when using the 2021 equation. Similar results for discrimination and calibration were observed when analyses were repeated in individuals with an eGFR between 15 and 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Supplementary Fig. S7B, Tables S22 and S23).

DISCUSSION

Kidney societies in the USA recommend immediate implementation of the 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation in clinical practice [17], but the impact of this recommendation outside the USA has not been well evaluated. In this Swedish healthcare-based cohort of more than 1.6 million participants from a single region of predominantly White ethnicity, we found that implementation of the 2021 equation would increase eGFR by a modest amount, with larger increases among the elderly and men. However, as a consequence, 1 in 10 individuals overall and 1 in 3 persons with CKD G3a–G5 would be reclassified to a higher eGFR category; eGFR by both the 2021 and 2009 equations was strongly associated with kidney, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes; and had similar prognostic accuracy (discrimination and calibration) to predict kidney failure in the Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

There may be several clinical implications when changing from the currently recommended 2009 CKD-EPI equation to the new 2021 CKD-EPI equation in a predominantly White population. On an individual level, although eGFR only increased by a modest amount (for most individuals between 3 and 5 mL/min/1.73 m2), it led to more than 30% of participants with CKD G3a–G5 being reclassified to a higher (less severe) KDIGO GFR category. Since GFR thresholds are used to guide medication initiation, discontinuation and dosing, reclassification to a different GFR category can have important implications. For instance, medications such as metformin, Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and direct oral anticoagulants may be continued longer as eGFR increases with the novel equation. Furthermore, cardio- and kidney-protective medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists may be initiated later as patients will take longer to reach a decreased GFR threshold [6, 7]. A higher eGFR with the new 2021 equation may also lead to later nephrologist referral, planning for dialysis and evaluation for kidney transplantation.

On a population level, implementation of the 2021 equation decreased the estimated prevalence of CKD G3a–G5 in our study, with the largest observed decreases amongst the elderly. Overall, the prevalence estimate in our cohort decreased from 5.1% to 3.8%, and for participants ≥65 years it decreased from 21.9% to 16.5%. In general, the elderly had larger eGFR increases with the 2021 equation than younger participants. This is a direct consequence of the change in the age coefficient in the 2021 equation [16]. Reclassified individuals were therefore older, and consequently also had more comorbidities and used more medications, compared with non-reclassified individuals. Understandably, reclassified individuals had a higher risk of mortality and cardiovascular events than non-reclassified individuals after accounting for differences in eGFR, with adjustment for age negating these associations. In NRI analyses, we observed that 11.6% of individuals who experienced KFRT were ‘inappropriately’ reclassified to a lower risk KDIGO category, and 9.9% of patients who did not experience KFRT were ‘appropriately’ reclassified to a lower risk KDIGO category. We note that when interpreting these proportions, it should be taken into account that the denominator for the event NRI is much smaller than the denominator for the nonevent NRI. Three recent studies have assessed the effects of changing from the 2009 to the 2021 equation on CKD prevalence: a Danish study found that replacing the 2009 by the 2021 CKD-EPI equation would decrease CKD prevalence from 5.5% to 4.2% [32]. Another study in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system found that adoption of the new equation increased the proportion of Black individuals and decreased the proportion of non-Black individuals with CKD G3–G4 [33]. Lastly, using data from NHANES the CKD-EPI Collaboration showed that the 2021 equation would decrease CKD prevalence by 1.5% among non-Black individuals [16]. These findings are congruent with ours.

An important finding is that eGFR by both equations was strongly associated with kidney, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes, and had similar discrimination for KFRT, all-cause or cardiovascular mortality, and MACE. Both eGFR equations had equal prediction performance for 5-year kidney failure risk when using the Kidney Failure Risk Equation. Discrimination was virtually identical and calibration was slightly better for the 2021 equation. We observed that the Kidney Failure Risk Equation significantly overestimated the risk of kidney failure in our population, in line with observations from a recent European study [34]. This may partly be attributed to the fact that the competing risk of death was not taken into account when developing this equation, which will overestimate risks especially under a longer prediction horizon and a high risk of the competing event [35]. A recent analysis of the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) investigated the predictive accuracy of five CKD-EPI creatinine or cystatin C equations on 2-year risk of end-stage kidney disease using the Kidney Failure Risk Equation; in keeping with our findings, the 2009 and 2021 creatinine-based equations showed similar discrimination and calibration [36].

From a clinical and public-health perspective, we feel that our results suggest caution before directly transitioning to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in non-US predominantly White populations, especially since the new equation has larger bias in non-Black individuals (–3.9 vs –0.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 2021 and 2009 equation, respectively) compared with measured GFR [16]. Although additional factors (such as equity) should be taken into account when making this decision, our data suggest that it would affect a large population who have CKD G3–G5 with the 2009 equation. It is possible that other European-derived eGFR equations [such as the European Kidney Function Consortium (EKFC) or Lund-Malmö equation] may better approximate measured GFR (mGFR) and/or predict risks in European populations, but this is beyond the scope of our analysis and requires further investigation. Because our data show that both equations have similar predictive ability for adverse outcomes, including kidney failure, mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, this suggests that both equations can be used for prognostic research.

The strengths of our study include the inclusion of a large population with median 10 years of follow-up, virtually no loss to follow-up, and validated KFRT endpoints. Our study also has limitations. We had no data on race, because Sweden does not allow collection of such data to prevent discrimination. Nevertheless, only a small proportion of citizens in our cohort were born in African countries and emigration from African countries has been traditionally considered low [25]. Findings apply to healthcare users from Stockholm, and extrapolation to other regions or countries should be done with caution. However, we feel results may inform other systems with similar White ethnic predominance. Our cohort depends on having creatinine measured in connection with a healthcare encounter, which may lead to a selected sample. Nevertheless, creatinine testing is common in healthcare and we have shown to capture >99% of Stockholm citizens with cardiovascular disease or diabetes, and >90% of citizens aged 65 years or above [37]. Thus, we feel that our results are generalizable to these clinically relevant groups who interact with the healthcare system and are seen by doctors. We required only one creatinine test for inclusion for the same reasons, since applying the chronicity criterion of at least two eGFR measurements <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is likely to lead to a selective population [19]. We focused on comprehensively comparing the 2021 vs 2009 CKD-EPI equations, because they are widely used in clinical practice and research throughout the world. A limitation is that we did not evaluate eGFR equations using both creatinine and cystatin C measures. This is an issue that warrants investigation given that these equations more accurately approximate mGFR [16] and predict adverse outcomes [38, 39] compared with eGFR equations based on creatinine or cystatin C alone.

We conclude that implementing the 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation in a predominantly White health system from Sweden raises eGFR by a modest amount (larger at older age and men), but results in the shifting of a major proportion of CKD patients to a higher eGFR category. Furthermore, eGFR by both equations strongly predicted outcomes, with similar calibration and discrimination. Awareness of these implications is important for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policy makers when evaluating transitioning to the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in non-US health systems.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Edouard L Fu, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Josef Coresh, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Morgan E Grams, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA; Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Catherine M Clase, Departments of Medicine and Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Carl-Gustaf Elinder, Division of Renal Medicine, Department of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Julie Paik, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Chava L Ramspek, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Lesley A Inker, Division of Nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Andrew S Levey, Division of Nephrology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Friedo W Dekker, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Juan J Carrero, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

FUNDING

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Swedish Research Council (#2019–01059), the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation and the Westman Foundation. E.L.F. acknowledges support by a Rubicon Grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). C.L.R. was supported by a grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (20OK016). M.E.G. is supported by NIH grants K24 HL155861, R01 DK115534 and R01 DK100446.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Research idea and study design: all coauthors; data acquisition: J.J.C.; data analysis/interpretation: all authors; statistical analysis: E.L.F., C.L.R.; drafting of manuscript: E.L.F.; supervision or mentorship: F.W.D., J.J.C. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, approves the submitted version, accepts personal accountability for the author's own contributions, and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on a reasonable request to the corresponding author

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

J.J.C. acknowledges consultancy for AstraZeneca, Bayer and Fresenius Kabi, and research funding from AstraZeneca, Amgen and Astellas, all outside the submitted work. C.M.C. has received consultation, advisory board membership or research funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Leo Pharma, Astellas, Janssen, Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Baxter, all outside the submitted work. J.C. is on the scientific advisory board for Healthy.io. None of the other authors declares relevant financial interests that would represent a conflict of interest. J.C., M.E.G., L.A.I. and A.S.L. have been involved in the development of the 2009 and 2021 CKD-EPI equations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013; 3: 1–150 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RLet al. . Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2017; 389: 1238–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CHet al. . KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2014; 63: 713–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME.. Chronic kidney disease diagnosis and management: a review. JAMA 2019; 322: 1294–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen TK, Sperati CJ, Thavarajah Set al. . Reducing kidney function decline in patients with CKD: core curriculum 2021. Am J Kidney Dis 2021; 77: 969–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheung AK, Chang TI, Cushman WCet al. . Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2021; 99: 559–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Boer IH, Caramori ML, Chan JCNet al. . Executive summary of the 2020 KDIGO Diabetes Management in CKD Guideline: evidence-based advances in monitoring and treatment. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 839–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delgado C, Baweja M, Burrows NRet al. . Reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney diseases: an interim report from the NKF-ASN task force. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32: 1305–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lucas A, Wyatt CM, Inker LA.. Removing race from GFR estimates: balancing potential benefits and unintended consequences. Kidney Int 2021; 100: 11–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Powe NR. Black kidney function matters: use or misuse of race? JAMA 2020; 324: 737–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levey AS, Titan SM, Powe NRet al. . Kidney disease, race, and GFR estimation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grubbs V. Precision in GFR reporting: let's stop playing the race card. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1201–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gopalakrishnan C, Patorno E.. Time to end the misuse of race in medicine: cases from nephrology. BMJ 2021; 375: n2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gama RM, Kalyesubula R, Fabian Jet al. . NICE takes ethnicity out of estimating kidney function. BMJ 2021; 374: n2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sehgal AR. Race and the false precision of glomerular filtration rate estimates. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173: 1008–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh Jet al. . New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 1737–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DCet al. . A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32: 2994–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jager KJ, Ocak G, Drechsler Cet al. . The EQUAL study: a European study in chronic kidney disease stage 4 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: iii27–iii31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vestergaard SV, Christiansen CF, Thomsen RWet al. . Identification of patients with CKD in medical databases: a comparison of different algorithms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 16: 543–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fu EL, Evans M, Carrero JJet al. . Timing of dialysis initiation to reduce mortality and cardiovascular events in advanced chronic kidney disease: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2021; 375: e066306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zacharias HU, Altenbuchinger M, Schultheiss UTet al. . A predictive model for progression of CKD to kidney failure based on routine laboratory tests. Am J Kidney Dis 2021;385: 1737–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nyman U, Grubb A, Larsson Aet al. . The revised Lund-Malmo GFR estimating equation outperforms MDRD and CKD-EPI across GFR, age and BMI intervals in a large Swedish population. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 52: 815–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carrero JJ, Elinder CG.. The Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project: fostering improvements in chronic kidney disease care. J Intern Med 2022; 291: 254–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CHet al. . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/sq/117607 . [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward Met al. . Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA 2012; 307: 1941–1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramspek CL, Teece L, Snell KIEet al. . Lessons learnt when accounting for competing events in the external validation of time-to-event prognostic models. Int J Epidemiol 2021; 51: 615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium , Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BCet al.. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375: 2073–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med 2011; 30: 11–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith Jet al. . A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA 2011; 305: 1553–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria,2019. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vestergaard S, Heide-Jørgensen U, Birn Het al. . Effect of the refitted race-free eGFR formula on the CKD prevalence and mortality in the Danish population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022; 17: 426–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gregg LP, Richardson P, Akeroyd Jet al. . Effects of the 2021 CKD-EPI Creatinine eGFR Equation among a National US Veteran Cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 17: 283–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ramspek CL, Evans M, Wanner Cet al. . Kidney failure prediction models: a comprehensive external validation study in patients with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32: 1174–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ravani P, Fiocco M, Liu Pet al. . Influence of mortality on estimating the risk of kidney failure in people with stage 4 CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 2219–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bundy JD, Mills KT, Anderson AHet al. . Prediction of end-stage kidney disease using estimated glomerular filtration rate with and without race: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 305–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Runesson B, Gasparini A, Qureshi ARet al. . The Stockholm CREAtinine Measurements (SCREAM) project: protocol overview and regional representativeness. Clin Kidney J 2016; 9: 119–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Arnlov Jet al. . Cystatin c versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 932–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lees JS, Welsh CE, Celis-Morales CAet al. . Glomerular filtration rate by differing measures, albuminuria and prediction of cardiovascular disease, mortality and end-stage kidney disease. Nat Med 2019; 25: 1753–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on a reasonable request to the corresponding author