October 31, 2022

The following paper is related to “Elements of Accountable Communities for Health: A Review of the Literature” (Mongeon, Levi, and Heinrich, 2017). This paper has been previously released in draft form as a background paper to inform participants of the August 2021 webinar “Accountable Communities for Health: What We Are Learning From Recent Evaluations” held by The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health and the Funders Forum on Accountable Health.

Background

Accountable Communities for Health (ACHs) are multisector, community-based partnerships that bring together health care, public health, social services, other local partners, and residents to address the unmet health and social needs of the individuals and communities they serve. These initiatives are referred to by several different titles, including accountable care communities, coordinated care organizations, and accountable health communities, among others, but for this discussion paper, the terms “accountable communities for health (ACHs)” and “accountable health model” will be used to generally describe the concept. The term “accountable” is often part of the nomenclature for these models, signifying an entity’s formal responsibility for the health of the community and a two-way, collaborative relationship. However, as this paper will discuss, specific mechanisms for upholding accountability (such as reporting and financial mechanisms) are often absent or underdeveloped in practice. Solidifying and scaling such mechanisms is an important growth area for these models. The Funders Forum on Accountable Health—a collaborative of philanthropic and public sector funders of these multisector partnerships—has identified more than 125 ACHs across the country at different stages of development (George Washington University [GWU], n.d.-a). Implementation of the accountable health model varies considerably depending on the initiative’s goals, priorities, and unique needs of the communities in which they operate. Nevertheless, all ACHs share several common elements, including a shared vision, an inclusive governance structure, strategies for sustainability and funding, and a commitment to hold themselves accountable to community stakeholders and advance equity in the community.

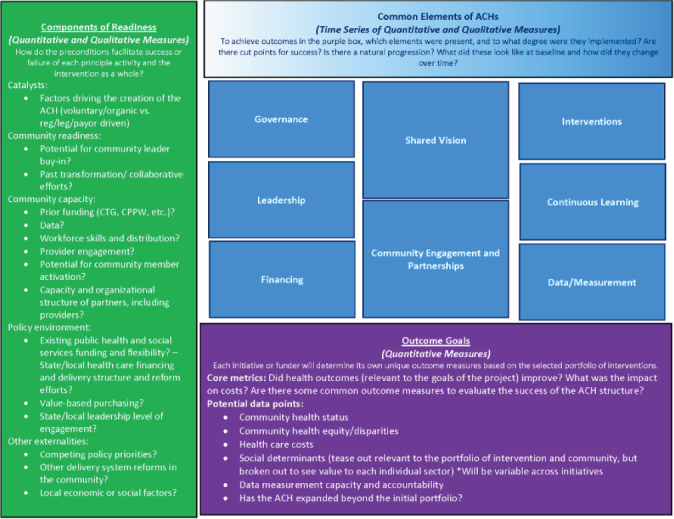

In acknowledgment of the diversity of accountable health models and the importance of better understanding “what works” across initiatives, in 2018, the Funders Forum on Accountable Health—with input from public and private funders, evaluation experts, and practitioners—developed the Common Assessment Framework for Assessing ACHs (Common Assessment Framework), built from a set of principles about the common elements of these multisector partnerships (see Figure 1) (Levi et al., 2018; GWU, 2017). The Common Assessment Framework identifies three critical areas of assessment of ACHs—common elements, components of readiness, and outcome goals—and offers a set of assessment questions developed to illuminate two key lines of inquiry:

FIGURE 1. The Common Assessment Framework’s Critical Areas of Assessment for Accountable Communities for Health.

SOURCE: The Funders Forum on Accountable Health. 2018. A Common Framework for Assessing Accountable Communities for Health. Reprinted with permission.

-

1.

What elements, and in what dose, are central to the success of an ACH?

-

2.

Which of the various approaches to ACHs will best match the needs of a given community?

In the years since the development of the Common Assessment Framework, several key lessons have emerged from recent evaluations of the accountable health model—most notably, the value of the ACH structure in and of itself to facilitate collaboration and shared decision making among diverse people and organizations to solve complex problems in their communities. ACHs are, above all, about changing how a community creates the conditions for health and how it shares power, particularly among low-income populations, people of color, and other underserved populations. This capacity has been demonstrated as ACHs across the country were able to pivot quickly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic to provide crucial health and social services to populations most in need.

In August 2021, the Funders Forum on Accountable Health hosted a webinar on key findings from the recent evaluations of four accountable health models: The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI) Accountable Health Communities demonstration, the California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative (CACHI), the BUILD (Bold, Upstream, Integrated, Local, Data-Driven) Health Challenge program, and the Washington State Accountable Communities of Health. Webinar materials, including the list of presenters and the webinar recording, are available on the Funders Forum on Accountable Health website (GWU, n.d.-b).

Each of the four accountable health models described in this paper has unique goals and priorities to address the needs of the populations and communities they serve. The models were established through different means and have taken different approaches to achieve, to some degree, the common elements that comprise an ACH. Notably, at their inception, accountability and equity were largely aspirational goals, most often without actionable strategies in place; the initiatives’ individual visions of what it means to be accountable to and advance equity within the communities they serve have evolved over time. And although there are several other initiatives planned or ongoing across the country, the evaluations of these four accountable health models, which have all been in progress for at least five years, provide practitioners and policy makers with an early perspective on what we are learning about the critical elements for success in effecting systems change in communities.

This discussion paper describes each of these four accountable health models and their evaluation designs. Using the Common Assessment Framework as a guide, this paper organizes key themes and cross-cutting findings in the three critical areas of assessment: common elements, components of readiness, and outcome goals (see Figure 1). The paper concludes with a discussion of (a) what transformative systems change for health, well-being, accountability, and equity looks like; (b) the implications of these findings for making the value proposition case for ACHs and other similar multisector partnerships; and (c) several policy considerations and opportunities for practitioners and policy makers to advance the model moving forward.

Accountable Health Model Evaluations Design

CMMI Accountable Health Communities Model

In 2017, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) launched the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model to test whether connecting Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries to community services that may address their health-related social needs (HRSNs) (including housing instability, food insecurity, transportation problems, utility difficulties, and interpersonal violence) can improve health outcomes and reduce costs (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2021). A total of $157 million was allocated to the model, which has a 5-year period of performance ending in April 2022. CMMI began beneficiary screening in the summer of 2018.

Twenty-eight participating organizations, including several health plans and health information exchanges, a city health department, community-based organizations, and hospitals and integrated health systems, received funding through cooperative agreements. These agreements allowed them to act as bridge organizations in their communities and implement the AHC Model in collaboration with state Medicaid agencies, clinical delivery sites that conduct the universal screening to identify Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries with HRSNs, and community service providers, among other stakeholders. The bridge organizations’ geographic target areas included both partial and full coverage of their counties and cities and, in two cases, covered the entire state.

The AHC model is composed of two tracks that test the effect of two distinct interventions on total health care costs, inpatient and outpatient health care utilization, and health status:

The Assistance Track (11 bridge organizations) tests universal screening to identify Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries with core HRSNs, referral to community services, and navigation assistance to connect beneficiaries with the community services they need. Navigation-eligible beneficiaries are randomly assigned to either the navigation intervention group or the control group. The evaluation compares quantitative outcomes between the groups to identify the impacts of the intervention.

The Alignment Track (18 bridge organizations) tests universal screening, referral, and navigation, plus engaging key stakeholders in community-level continuous quality improvement. This quality improvement includes an advisory board to ensure resources are available to address HRSNs, data sharing to inform a gap analysis, and a quality improvement plan. The community gap analysis aims to identify persistent unmet social needs using data from screenings and referrals as well as other sources. The evaluation establishes a comparison group drawn from the Assistance Track control group to measure the impact of screening, referral, and navigation plus community-level continuous quality improvement.

The AHC model evaluation is ongoing, and CMMI released the AHC model’s first evaluation report in December 2020 (RTI International, 2020). The evaluation aims to assess model implementation, impacts, and how contextual factors and implementation affect impacts. The evaluation uses mixed methods, including surveys and interviews with bridge organizations, partners, and beneficiaries; screening and navigation data; claims data analysis; and randomized and matched comparison group design where they assess impact on cost and utilization outcomes.

California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative (CACHI)

The California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative (CACHI), launched in 2016, is funded by a consortium of private funders, including The California Endowment, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Kaiser Foundation, Sierra Health Foundation, California Wellness Foundation, Social Impact Exchange, and Wellbeing Trust (CACHI, 2022b). CACHI aims to transform the health of entire communities, not just individual patients, by bringing together community institutions such as hospitals, public health agencies, social services, schools, other sectors, and local residents. One of their key indicators of transformation is “collective accountability” among these partners for operationalizing the initiative. CACHI began with six grantee sites and now supports 13 urban, rural, and suburban communities in all parts of the state. Backbone organizations include public health departments, community-based organizations, and one health system. Each site develops a portfolio of interventions that attend to at least three of five domains: clinical, community, clinical-community, environment, and policy.

CACHI’s evaluation aims to assess progress toward achieving local and initiative goals, the “added value” of ACHs as a model for community and systems transformation (and the role of the portfolio of interventions in catalyzing these changes), model sustainability and spread, and health equity as part of identified milestones. For their most recent evaluation, evaluators conducted annual site visits (in person and virtually), key informant interviews, partnership surveys, document analysis, and special surveys on specific topics such as COVID-19 response and health system engagement.

In January 2022, CACHI released its evaluation brief covering 2017 to 2021 (CACHI, 2022a).

The BUILD Health Challenge® Model

In 2015, a coalition of national and regional organizations partnered to launch The BUILD Health Challenge, including BlueCross BlueShield Foundation of South Carolina, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Communities Foundation of Texas, de Beaumont Foundation, Episcopal Health Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, Methodist Healthcare Ministries of South Texas, Inc., New Jersey Health Initiatives, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation (The BUILD Health Challenge, 2022). BUILD (Bold, Upstream, Integrated, Local, Data-Driven) is a national awards program designed to support partnerships between community-based organizations, health departments, hospitals and health systems, and residents working to address important health issues in their community. Each community collaborative leverages multisector partnerships and community input to address root causes of chronic disease, including the social determinants of health. Each collaborative focuses on implementing Bold (systems change), Upstream (social determinants of health), Local (community-driven), and Data-driven (community and clinical data) principles to foster systems-level changes and ultimately advance health equity.

To date, with support from 17 funders, BUILD has supported three cohorts totaling 55 community partnerships in 24 states and Washington, DC. Communities are awarded up to $250,000 over two years to implement their efforts to drive sustainable improvements in community health. The partnering hospitals and health system(s) in each award also commit a 1:1 match with financial and in-kind support to advance the partnership’s goals.

BUILD’s evaluation has evolved from a developmental approach in the early years to formative and summative approaches today. Equal Measure, the evaluation team, is working with the third BUILD cohort—18 cross-sector, community-driven partnerships that will last for 2.5 years, ending in 2022—to track change over time in the implementation of BUILD’s principles and the integration of equity in the work. In addition, the evaluation measures outcomes across partners involved in BUILD’s first and second cohorts, focusing on systems change, equity, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

BUILD’s second cohort results are available on BUILD’s website, with the third cohort results expected to be published in the summer of 2022 (The BUILD Health Challenge, 2019).

Washington State Accountable Communities of Health (Washington State HCA)

Washington State’s nine regional Accountable Communities of Health began in 2015 as part of the State Innovation Model, a CMMI cooperative agreement-funded initiative (Washington State HCA, 2022a). The scope and role of Accountable Communities of Health expanded with Washington’s Section 1115 Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment Project waiver, which launched in January 2017. As part of the Medicaid Transformation Project (MTP), the Accountable Communities of Health received a total of up to $1.1 billion in funding for regional health system transformation projects that benefit Medicaid beneficiaries (“up to” because a portion of the funding is performance-based). Accountable Communities of Health became responsible for the design and implementation of MTP projects, moving from a broad definition of improving population health in regions to an emphasis on clinical health system transformation.

The Health Care Authority (HCA) contracted with the Center for Community Health and Evaluation—working in collaboration with the University of Washington and the State Department of Social and Health Services—to evaluate the Accountable Communities of Health. The evaluation used a case study, logic model design to assess the development and impact of the Accountable Communities of Health on Healthier Washington goals. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from multiple sources to document Accountable Communities of Health’s progress and impact from 2015 to 2019. These data included observations of meetings, site visits, interviews with stakeholders, surveys of ACH participants, and extensive document reviews. The Center for Community Health and Evaluation released the Washington Accountable Communities of Health evaluation report in January 2019 (Center for Community Health and Evaluation, 2019).

An ongoing evaluation of the overall MTP by the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health Sciences University focuses on the overall Medicaid system performance, such as quantitative measures of access, quality, social outcomes, and expenditure changes from baseline (Washington State HCA, 2022b).

Key Themes and Learnings

The Funders Forum on Accountable Health’s Common Assessment Framework and its three critical areas of assessment are used here as a guide to organize key themes and learnings from each of the four accountable health model evaluations described above.

Components of Readiness

Components of readiness refer to the preconditions in a community that are essential to the successful startup of an ACH. The components of readiness most heavily emphasized in the evaluations were community readiness and capacity, which include:

potential for community leader buy-in

prior funding and transformation or collaborative efforts that brought major stakeholders together

data

workforce skills and distribution

provider engagement

potential for community member activation

capacity and organizational structure of partners

Qualitative and quantitative measures were critical in determining community readiness and capacity to undertake an ACH, including what assistance communities needed to develop and support the ACH’s operational infrastructure and its partners’ overall capacity.

All four initiatives reviewed in this paper found it helpful when different organizations and sectors had previous experience working together on projects or outside funding. At the same time, as multisector organizations began to implement initiatives, all commented on the importance of taking the time to build the relationships and trust required to keep everyone at the table. Most notably, the four initiatives found that provider engagement and community resident activation were the most important factors in implementing systems changes in their communities.

The four initiatives also found, however, that even with considerable readiness factors present, it took much more time than the anticipated weeks or months for the ACHs to develop governance structures and a shared vision—from six months to a year. Many factors accounted for this, including:

changing leadership in organizations

staff turnover

moving from informal to formal agreements

finding a shared language and building the trust necessary to engage community members in the process

reexamining community priorities and resources

In addition, all four initiatives cited data analytics and data sharing capacity as major challenges. At the onset of these initiatives, participating organizations were not equipped with the comprehensive infrastructure necessary to collect, analyze, and share data in support of initiative goals, especially with community-based organizations. In some cases, a lack of community resources and poorly equipped data systems made it difficult for ACHs to meet the goals of their portfolio of interventions and track outcomes.

Furthermore, though the initial organizational capacity to support the multisector partnership was important, where it was housed—as long as it was seen as a fair arbiter—was not. The organizational structure often changed over time, becoming independent entities or forming new partnerships to support the evolving organizations.

Common Elements of ACHs

Across all of the initiatives, all the common elements of ACHs identified in the Common Assessment Framework, with equity as a major component throughout, are present (see Figure 2). The evaluations do not clearly indicate if one element was more important than the others, but they did suggest that each element reinforced others as communities engaged in change. At the same time, evaluations across the board noted the importance of a shared vision and a focus on equity for moving toward each ACH’s goals, and highlighted their experiences with technical assistance, data, and financial sustainability.

FIGURE 2. Essential Elements of Accountable Communities for Health.

SOURCE: Developed by authors.

The relationship building and trust that developed as diverse sectors came to a common table to address community priorities is especially noteworthy. Although all of the initiatives started with elements of health equity as part of the overall goals, equity became more explicit over time. For some sites, equity was not a focus until the advent of COVID-19, when the stark realities of health and social inequities became readily apparent for all to see. An equity lens is now explicit in the CACHI, BUILD, and Washington State accountable health models, as illustrated by their inclusion of community residents in leadership positions, partnerships with community-based organizations, and transparency in decision making regarding resource allocation. These accountable health models are also exploring new approaches to structuring and supporting partnerships that address upstream community-level determinants of health.

Funders of these initiatives also provided opportunities for technical assistance from a variety of subject matter experts and learning communities where participants could share successes and challenges. All but the CMMI initiative had evaluations that provided feedback to the individual projects so that improvements could be made over the course of the demonstration. Technical assistance included a variety of topics, such as the role of ACHs in improving equity, backbone functions for ACHs, governance and leadership, and data analysis and sharing. Continuous learning, genuine community engagement, and power-sharing approaches across organizations were also important topics.

As stated previously, data gathering, analysis, and data sharing across sectors have been a challenge for all of the initiatives, even for ACHs built on data exchanges. The CMMI demonstrations focused on documenting screening and referral for HRSNs but struggled with platforms that could provide feedback to clinical providers, including the community-based organizations providing essential social services. The other initiatives experienced challenges with trust among the organizations trying to exchange information, lack of social services infrastructure, and HIPAA certification and requirements.

The financial sustainability of ACHs is an ongoing topic of concern. ACHs are often initiated with philanthropic or publicly funded startup grants, but additional resources are required to sustain both the programmatic and core infrastructure functions of these organizations in the long term. Identifying and obtaining financial support for core infrastructure functions is of particular concern because, although experts have identified multiple credible funding options for ACH infrastructure activities, “there is no dedicated or explicit source of funding for these critical functions” (Hughes and Mann, 2020). Some ACHs have developed services they can charge for, and others have developed relationships with insurance providers such as Medicaid or private insurers that participate in Medicaid contracts. In Washington State, several ACHs used resources from the MTP to fund Community Resiliency Funds, which many used to fund improvements in the social determinants of health in their communities. The CACHI projects were encouraged to establish Wellness Funds, which could be funded with dollars from a variety of sources, such as managed care organizations participating in the state Medicaid program. The ACHs with these special funds found them to be extremely helpful in meeting the needs of populations at high risk during the height of the pandemic. Nevertheless, developing the business case for ACHs remains a challenge.

Outcome Goals for ACHs

Each ACH develops goals and outcome metrics based on the unique priorities of their communities. Nevertheless, the four evaluations revealed cross-cutting goals and outcomes related to community health status, health equity and disparities, health care costs, social determinants, data measurement capacity, and accountability to the communities they serve.

All of the initiatives monitored community health status with common measures such as the Community Health Rankings but did not expect to see major changes because the relatively short time frame of ACH grant periods makes it difficult to demonstrate progress on the long-term impacts on community health outcomes. That said, Washington State had specific measures Accountable Communities of Health were required to report on, and there were some observed changes, such as decreased opioid overdose deaths and overall improvement in measures related to substance and opioid use disorders. There were also positive changes related to specific site goals; for example, Collaborative Cottage Grove—a BUILD community in Greensboro, North Carolina—reduced emergency department utilization for children with asthma by improving housing for low-income families (Wright et al., 2021).

The CMMI initiative’s Alignment Track bridge organizations were required to conduct community gap analyses, which could then serve as the basis for community engagement to resolve common areas of need. The initiative’s primary focus, however, was to determine whether addressing HRSNs would impact health care service utilization. An early evaluation found a lack of any community-level results identified in this model. The other three initiatives found that their conceptualizations of accountability and equity evolved over time, from an initial focus on specific health outcomes to a broader understanding of equity through community engagement and power sharing. The CACHI initiative has explicit goals related to the role of distributed leadership and the development and implementation of the portfolio of interventions in advancing health equity. Washington State HCA focused on health disparities, stratifying data by race/ethnicity and income. The HCA also conducted three health equity-related events—including two tailored for Accountable Communities of Health—on building equity into Washington State’s Health System, managing change and advancing equity, and community health through an equity lens (CHSE, 2021). BUILD integrated a health equity focus into all of the community interventions and an inclusive approach to decision making. All of the initiatives reported that in their response to the pandemic, the ACHs were able to respond quickly to populations most in need of social services and medical care. For example, Washington State’s MTP Evaluation Rapid-Cycle Report from March 2021 provides evidence that Accountable Communities of Health have sought to address equity in the core elements of the ACH model and “have contributed to the state’s COVID-19 response by leveraging their existing community partner networks and information exchange infrastructure to meet community needs during the pandemic” (Center for Health Systems Effectiveness [CHSE], 2021).

Health care costs and utilization rates (specifically the reduction of both) are major considerations for the CMMI and Washington State evaluations. The CMMI AHC model evaluation determined that sites are successfully identifying higher cost and utilization beneficiaries, and the rates of navigation assistance acceptance among these beneficiaries are high. Early findings also show that the AHC model has promising effects on reducing emergency department utilization for Medicare beneficiaries, but no Medicare savings or impacts on other outcomes were reported in the first year. Future reports on the AHC model will also include impacts on Medicaid beneficiaries, who comprise almost three-quarters of model enrollees. Washington State’s separate evaluation on the overall MTP that is addressing health care costs and utilization showed mixed results on health care costs, especially when accounting for racial and ethnic differences (Washington State HCA, 2022b). Health care costs were not a focus of the CACHI and BUILD evaluations, but working to define and assess the value of the ACH model beyond traditional return on investment metrics is important to both initiatives (Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, 2021).

Across the initiatives, addressing the social determinants of health was a clear focus, but in practice, activities were most closely linked to individual needs or HRSNs. Most of the sites across the initiatives used community health workers to bridge the clinical-community gap and provide necessary navigation services. As stated above, the CMMI initiative effectively identified high-need, high-cost beneficiaries, many of whom had multiple HRSNs, above and beyond the five core needs targeted by the model. Food insecurity was the most commonly reported HRSNs, followed by housing and transportation. And although, as previously stated, acceptance of navigation assistance was high among beneficiaries, at early stages of implementation there was little evidence of navigation effectiveness in resolving beneficiaries’ HRSNs, likely due to loss to follow-up, burnout and turnover of staff, and lack of community resources. In Washington State, although there were efforts to build capacity to address social determinants of health, the sites most often focused on individual needs. Both BUILD and CACHI emphasized upstream social determinants of health during their implementation. Overall, however, there was much more focus on HRSNs and less evidence on efforts addressing upstream social determinants.

All of the initiatives reported experiencing major challenges with ACH performance measurement and formal structures for demonstrating accountability to communities served. Washington State has measures required as part of the MTP that are linked to performance, but more work is needed on specific ACH performance measures. Reporting back to communities with actionable information is a work in progress.

Further Considerations

The evaluations discussed here not only presented the four initiatives’ progress toward meeting their outcome goals but also illustrated that each initiative aims to be an agent of change within their community, and that, in and of itself, has value beyond the traditional outcomes of an initiative’s interventions.

All four evaluations provided a glimpse into what transformative systems change for health, well-being, accountability, and equity looks like, with their most powerful findings relating to the development and evolution of targeted approaches to address equity in communities and power sharing resulting from the inclusion of community residents in decision making, governance, and resource allocation. In Washington State, for example, ACHs are the regional organizations integrating transformations, large and small, in the health care system as they address equity and power sharing in the region. They are finding that transformation requires a different approach to the traditional top-down community health planning approach built on trust, respect, and communication. BUILD has established health equity as an explicit value, goal, and expectation across all sites and centers on the questions “how do we hold ourselves accountable to our mission?” and “how is equity operationalized in our work?” Similarly, CACHI has made aligning and making systems accountable for health and equity an expectation of their sites. And although the CMMI evaluation did not explicitly address it, equity was part of the CMMI AHC model’s work, particularly as the sites addressed disparities exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. Future evaluations may consider co-designing evaluations with sites and community residents with lived experience to produce a tool more adept at capturing local systems changes and shifts in community dynamics, including resident engagement in decision making and diversity in funding community-based organizations.

ACHs utilized their established partnerships and relationships to marshal and coordinate resources to respond quickly to COVID-19. In their response to the pandemic, multisector collaboratives highlighted the need to adopt an explicit focus on equity and develop community-specific interventions to address inequities associated with new and existing partners. The major takeaway from all the initiatives examined is that through this process, they have made progress on the pathway toward building more equitable communities.

Moving forward, in light of the current administration’s commitment to addressing equity through multisector partnerships, the evaluations of these four ACH models raise several policy considerations.

First, how do stakeholders move beyond the traditional, transactional way of assessing an ACH’s interventions to capturing transformative system change and its impact on well-being and equity? Importantly, what do we mean by value in relation to the accountable health model? In spring 2021, the Funders Forum on Accountable Health, in collaboration with CACHI, released the issue brief “Advancing Value and Equity in the Health System: The Case for Accountable Communities for Health” (Wright et al., 2021). In the brief, the authors examine an alternate framework for defining and assessing value that moves beyond return on investment to capture the transformational nature of an ACH’s work, which happens through relationships that generate innovation and new ways of working together. This transformational work, as well as the trust building that is required, often takes more time and effort than anticipated but is vital for long-term success.

Second, how do stakeholders measure the role of ACHs in catalyzing alignment? ACHs work across sectors to eliminate siloed, program-by-program interventions and establish collective accountability among stakeholders and the community to drive sustainable systems changes and outcomes. They also aim to level the playing field, so communities have a real say in defining problems and advancing solutions that prioritize equity. These are the skills and activities needed for system change. Transformation happens through relationships that generate innovative approaches to solving problems. The true value lies in the architecture for change that is created and persists in each community after the building is done.

Finally, the role of payment systems and siloed budgets at the state and federal levels needs to be considered in the development of an alternative return on investment framework. The fee-for-service reimbursement model in health care services makes it difficult for health care systems to address upstream factors, and siloed budgets create a “wrong pocket” problem where ACHs generate a return, but the value of the return accrues to other organizations in the community, not the ACH that made the initial investment. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, states, and commercial payers are all rethinking how to pay for care, including improvements in the social determinants of health. If equity and social determinants of health concepts are built into how we pay for care, it will be easier to recognize the value ACHs generate.

Conclusion

All four evaluations of accountable health models have provided evidence that engaging multiple stakeholder groups is important in addressing community priorities. The initiatives’ individual visions of what it means to be accountable to and advance equity within the communities they serve continue to evolve over time. Being accountable to communities served, particularly through community engagement and power sharing, are central to achieving systems change. This engagement requires strengthening relationships and taking the time to build trust. ACHs can be a vehicle for moving toward greater equity in our communities across the country, no matter the political climate.

Acknowledgments

This paper benefited from the thoughtful input of Daniella Gratale, Nemours; and Nathanial Counts, Mental Health America.

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author sand not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: Helen Mittman, Janet Heinrich, and Jeffrey Levi report grants from The California Endowment, grants from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Episcopal Health Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation during the conduct of the study; and grants from The California Endowment, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Episcopal Health Foundation, and the Kresge Foundation outside the submitted work.

Contributor Information

Helen Mittmann, George Washington University.

Janet Heinrich, George Washington University.

Jeffrey Levi, George Washington University.

References

- 1.Mongeon M, Levi J, Heinrich J. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2017. Elements of accountable communities for health: A review of the literature. Discussion Paper. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative (CACHI) Accountable Communities for Health 2017-21 Interim Report. 2022a. [May 24, 2022]. https://cachi.org/uploads/resources/CACHI-2022-Eval-Brief_1-14-21-Final.pdf .

- 3.California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative (CACHI) Home. 2022b. [May 24, 2022]. https://cachi.org/

- 4.Center for Community Health and Evaluation (CCHE) Regional collaboration for health system transformation: An evaluation of Washington’s Accountable Communities of Health. 2019. [May 24, 2022]. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/cche-evaluation-report-for-ACHs.pdf .

- 5.Center for Health Systems Effectiveness (CHSE) Medicaid Transformation Project Evaluation: Update on Performance, Health Equity, and COVID-19. 2021. [May 24, 2022]. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/medicaid-transformation-evaluation-rapid-cycle-march-2021.pdf .

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Accountable Health Communities Model. 2021. [May 24, 2022]. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm .

- 7.George Washington University. A Common Framework for Assessing Accountable Communities for Health. 2017. [May 24, 2022]. https://accountablehealth.gwu.edu/sites/accountablehealth.gwu.edu/files/Assessment%20Qs_July%2017_Letterhead.pdf .

- 8.George Washington University. Funders Forum on Accountable Health. [May 24, 2022]. n.d.-a. https://accountablehealth.gwu.edu/ACHInventory .

- 9.George Washington University. Publications. [May 24, 2022]. n.d.-b. https://accountablehealth.gwu.edu/forum-analysis/publications .

- 10.Hughes DL, Mann C. Financing the Infrastructure of Accountable Communities for Health is Key to Long-Term Sustainability. Health Affairs. 2020;39(4) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi J, Fukuzawa DD, Sim S, Simpson P, Standish M, Wang Kong C, Weiss AF. Developing a Common Framework for Assessing Accountable Communities for Health. Health Affairs Forefront. 2018. [May 24, 2022]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20181023.892541/full/

- 12.RTI International. Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Model Evaluation: First Evaluation Report. 2020. [May 24, 2022]. https://innovation.cms.gov/data-and-reports/2020/ahc-first-eval-rpt .

- 13.The BUILD Health Challenge. Results from BUILD’s Second Cohort: Learnings, Insights, and a Look at What’s Next. 2019. [May 24, 2022]. https://buildhealthchallenge.org/blog/results-from-builds-second-cohort-learnings-insights-and-a-look-at-whats-next/

- 14.The BUILD Health Challenge. Home. 2022. [May 24, 2022]. https://buildhealthchallenge.org/

- 15.Washington State Health Care Authority (WSHCA) Accountable Communities of Health (ACHs) 2022a. [May 24, 2022]. https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/medicaid-transformation-project-mtp/accountable-communities-health-achs .

- 16.Washington State Health Care Authority (WSHCA) Reports. 2022b. [May 24, 2022]. https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/medicaid-transformation-project-mtp/reports .

- 17.Wright BJ, Masters B, Heinrich J, Levi J, Linkins KW. Advancing Value and Equity in the Health System: The Case for Accountable Communities for Health. 2021. [May 24, 2022]. https://cachi.org/uploads/resources/CACHI-Value-Brief_-Final_5-21-21.pdf .