Abstract

Background

The COVID‐19 pandemic significantly disrupted nursing home (NH) care, including visitation restrictions, reduced staffing levels, and changes in routine care. These challenges may have led to increased behavioral symptoms, depression symptoms, and central nervous system (CNS)‐active medication use among long‐stay NH residents with dementia.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, cross‐sectional study including Michigan long‐stay (≥100 days) NH residents aged ≥65 with dementia based on Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessments from January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2021. Residents with schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, or Huntington's disease were excluded. Outcomes were the monthly prevalence of behavioral symptoms (i.e., Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale ≥ 1), depression symptoms (i.e., Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ]—9 ≥ 10, reflecting at least moderate depression), and CNS‐active medication use (e.g., antipsychotics). Demographic, clinical, and facility characteristics were included. Using an interrupted time series design, we compared outcomes over two periods: Period 1: January 1, 2018–February 28, 2020 (pre‐COVID‐19) and Period 2: March 1, 2020–June 30, 2021 (during COVID‐19).

Results

We included 37,427 Michigan long‐stay NH residents with dementia. The majority were female, 80 years or older, White, and resided in a for‐profit NH facility. The percent of NH residents with moderate depression symptoms increased during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19 (4.0% vs 2.9%, slope change [SC] = 0.03, p < 0.05). Antidepressant, antianxiety, antipsychotic and opioid use increased during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19 (SC = 0.41, p < 0.001, SC = 0.17, p < 0.001, SC = 0.07, p < 0.05, and SC = 0.24, p < 0.001, respectively). No significant changes in hypnotic use or behavioral symptoms were observed.

Conclusions

Michigan long‐stay NH residents with dementia had a higher prevalence of depression symptoms and CNS active‐medication use during the COVID‐19 pandemic than before. During periods of increased isolation, facility‐level policies to regularly assess depression symptoms and appropriate CNS‐active medication use are warranted.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, dementia, depression, nursing homes, psychotropic drugs

Key points

Among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with ADRD, depression symptoms were higher during COVID‐19 (March 2020–June 2021) as compared to pre‐COVID‐19 (January 2018–February 2020).

The use of select CNS‐active medication classes (i.e., antipsychotic, antidepressant, antianxiety, and opioid medications) increased during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19.

Why does this paper matter?

Monitoring depression symptoms and CNS‐active medication use among long‐stay nursing home residents with ADRD during the pandemic in periods of reduced social contact and increased isolation is warranted to ensure appropriate depression management and medication use.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic significantly disrupted nursing home (NH) care, including required restrictions for visitors, volunteer and non‐essential healthcare personnel, and group and communal activities in NHs. 1 , 2 , 3 Staff shortages, due to possible or confirmed COVID‐19 infection or staff resignation, also resulted in changes in routine care. 4 , 5 Among long‐stay NH residents, the prevalence of depression symptoms, episodes of incontinence, and worsening cognitive function were observed during the pandemic. 6

Long‐stay NH residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) are likely more susceptible to poor outcomes related to increased risk of infection, routine care changes, and increased social isolation due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. 7 , 8 , 9 Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as agitation, depression, aggression, sleep problems, and apathy, occur in 97% of patients with advanced dementia. 10 , 11 Although non‐pharmacological methods are recommended as first‐line treatment for NPS, 12 it is likely that barriers (e.g., staff constraints and a lack of resources) to their use 13 increased during the pandemic. As a result, NH treatment of NPS symptoms may have more heavily relied on psychotropic medication use during the pandemic. Our preliminary work indicated that antidepressant use increased during the first 4 months of the pandemic among long‐stay NH residents with ADRD in Michigan. 14 However, it is unknown if these changes in psychotropic medication use persisted as the COVID‐19 pandemic progressed as well as the impact of the pandemic on NH residents' prevalence of depressive symptoms and behavioral disturbances.

This study compared a longer time before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic, as compared to our preliminary publication, to add to our knowledge of changes in mental health among long‐stay NH residents with ADRD. The objectives of this study were to compare the prevalence of behavioral symptoms, depression symptoms, and CNS‐active medication use among Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We hypothesized that behavioral symptoms, depression symptoms, and antidepressant medication use would be all higher among long‐stay NH residents with ADRD during the COVID‐19 pandemic than pre‐pandemic.

METHODS

Study design and population

A retrospective, cross‐sectional study was conducted in Michigan NHs from 2018 to 2021. Long‐stay NH residents aged ≥65 years with ADRD based on Minimum Data Set (MDS) assessments from January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2021 were eligible. 15 Long‐stay NH residents were defined as those who stayed in the NH for at least 100 days cumulatively each year, including carry‐over days from the previous year if that stay crossed over the calendar year, based on MDS assessment data. Residents were categorized as having ADRD for a given year if they met any of the following criteria: 1) Alzheimer's Disease, 2) Non‐Alzheimer's Dementia, or 3) International Classification of Diseases—Clinical Modification—10th Revision (ICD‐CM‐10) codes for ADRD (Table S1). We used the same cohort exclusions that CMS applies for its antipsychotic monitoring including removing residents with schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, and Huntington's disease. Lastly, we excluded residents with missing age, sex, or race demographic information.

Outcomes

Long‐stay residents in NH settings are mandated to have MDS assessments completed on a quarterly basis. We evaluated the prevalence of behavioral symptoms, depression symptoms, and CNS‐active medication use within facilities during the COVID‐19 pandemic, as recorded in MDS assessments. Outcomes were assessed on a monthly basis among residents with a qualifying assessment during the given month. Each resident was counted once in our monthly denominator even if they had multiple MDS assessments.

Behavioral symptoms

Behavioral symptoms were measured by the Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) derived from MDS items. 15 , 16 The frequency of behaviors and their value ranged from not exhibited (0), occurring 1–3 days (1), 4–6 days but less than daily (2), and daily (3). The ARBS is the sum of the values for physical or verbal behavioral symptoms directed towards others, other behavioral symptoms not directed towards others, and resident rejection of necessary care. 16 Behavioral symptoms were categorized as present if ARBS was ≥1.

Depression symptoms

Depression symptoms were measured by the MDS Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) resident mood interview or staff assessment of resident mood (observational version). 15 , 17 Depression symptoms were categorized as present if the resident or staff PHQ‐9 total severity score was ≥10 which reflects moderate or greater depression severity.

CNS‐active medication use

CNS‐active medication use included antipsychotic, antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and opioid medications. 15 We used the MDS items that assessed the number of days (range: 0–7) these medication classes were received during the last 7 days or since admission if the days were less than seven. 15 We categorized the use of each medication class as yes if one or more days were indicated and no if the number of days was 0 out of seven.

Demographics and nursing facility characteristics

We included age, sex, and race/ethnicity as demographic characteristics. Additional active diagnoses related to psychotropic medication use were included: anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder other than schizophrenia, and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We included the following NH facility characteristics from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) provider file: size (number of beds), hospital‐based or for‐profit status (yes/no). A facility was categorized as a highly rated facility for both overall or quality domains if their respective CMS 5‐star rating was 4 or 5 stars.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the demographics and clinical characteristics of Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD and NH facility characteristics in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021. Using an interrupted time series (ITS) design, we compared outcomes over two periods: Period 1: January 1, 2018 to February 28, 2020 [pre‐COVID] and Period 2: March 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021 (during COVID). We used the Cumby‐Huizinga test to examine each ITS model for autocorrelation and then refit our ITS model with appropriate lag and Newey‐West standard errors. The a priori level of significance was p < 0.05 and SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and Stata version 17.0 (College Station, TX) were used for analysis. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt.

RESULTS

A total of 53,451 Michigan long‐stay NH residents were identified, of which 37,427 (70%) with ADRD were included. The majority of long‐stay NH residents with ADRD were female, 80 years or older, and of White race/ethnicity (Table 1). Approximately 16% of long‐stay NH residents with ADRD were Black and 2% were classified as Other race/ethnicity. Over the 2018–2021 timeframe, up to 60% had depression, 43% had anxiety, 5% had bipolar disorder, 14% had a psychotic disorder other than schizophrenia, and 1% had a PTSD clinical diagnosis. The nursing facilities had on average 106 beds, were for‐profit status (70%), and over half had an overall or quality 5‐star rating of 4 or 5.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and nursing facility characteristics of Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias

| 2018, N = 22,480 | 2019, N = 21,928 | 2020, N = 20,137 | 2021, a N = 12,974 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean [SD]) | 84.5 (8.5) | 84.3 (8.6) | 84.1 (8.7) | 83.8 (8.8) |

| 65–79 years, % | 29.1 | 30.5 | 31.7 | 34.1 |

| ≥80 years, % | 70.9 | 69.5 | 68.3 | 65.9 |

| Female, % | 70.6 | 70.1 | 69.9 | 70.9 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| White | 82.3 | 81.6 | 81.1 | 81.7 |

| Black | 15.8 | 16.4 | 16.8 | 16.2 |

| Other | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Clinical diagnoses, % | ||||

| Depression | 58.4 | 58.4 | 58.9 | 59.5 |

| Anxiety | 43.0 | 42.7 | 42.6 | 41.9 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| Psychotic disorder | 13.0 | 13.5 | 14.4 | 14.3 |

| PTSD | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| Number of minimum data set assessments | 118,443 | 112,976 | 95,644 | 34,354 |

| Nursing facility characteristics | ||||

| Number of facilities | 424 | 429 | 428 | 422 |

| Number of beds, Mean (SD) | 106.1 (49.4) | 105.6 (49.3) | 105.7 (49.3) | 106.2 (48.9) |

| Hospital‐based, % | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 |

| For‐profit status, % | 69.3 | 69.7 | 69.6 | 69.9 |

| Overall 5‐star rating: 4 or 5, % | 54.5 | 54.8 | 54.7 | 54.7 |

| Quality 5‐star rating: 4 or 5, % | 68.2 | 68.3 | 68.2 | 67.8 |

Abbreviation: PTSD, post‐traumatic stress disorder.

Timeframe: January–June, 2021.

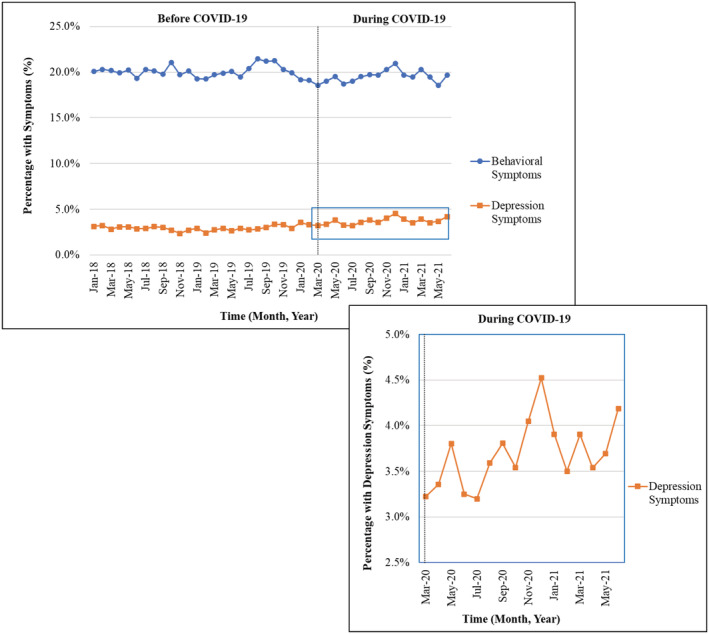

The prevalence of depression symptoms of at least moderate severity was higher during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19 (4.0% during COVID‐19 vs 2.9% pre‐COVID‐19, slope change = 0.03, p < 0.05) (Table 2 and Figure 1). No significant difference in behavioral symptoms was observed during the COVID‐19 period compared to pre‐COVID‐19 (19.9% vs 20.0%, slope change = 0.05, p = 0.31). The monthly observed prevalence of behavioral symptoms and depression symptoms in long‐stay NH residents with ADRD is provided in Table S2.

TABLE 2.

Interrupted time series analysis results for behavioral and depression symptoms among long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias pre‐COVID‐19 and during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

| Behavioral symptoms (ARBS ≥ 1) | Depression symptoms (PHQ‐9 ≥ 10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Period 1 (Jan 2018–Feb 2020): Pre‐COVID‐19 | ||||

| % Symptoms at beginning of period 1 (Jan 2018) | 20.0 | 2.9 | ||

| Slope during pre‐COVID‐19 period | 0.002 | −0.04, 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 |

| Period 2 (Mar 2020 – Jun 2021): During COVID‐19 | ||||

| Slope during COVID‐19 period | 0.05 | −0.02, 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.06* |

| Slope change pre‐ and during COVID‐19 | 0.05 | −0.04, 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.004, 0.06* |

| % Symptoms at end of period 2 (Jun 2021) | 19.9 | 4.0 | ||

Abbreviations: Est., estimate; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ARBS, Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale; PHQ‐9, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9.

Note: Residents with diagnoses of Huntington's disease, Tourette syndrome, or schizophrenia were excluded. Prevalence reported in the predicted percent from the interrupted time series model.

p < .05.

FIGURE 1.

Behavioral and depression symptoms in Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD), January 1, 2018 – June 30, 2021 The percentage of monthly behavioral symptoms [Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale ≥ 1] and monthly depression symptoms [Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 ≥ 10] was examined on all Minimum Data Set assessments per resident for a given month. Residents with Huntington's disease, Tourette syndrome, and schizophrenia were excluded. Enlargement portrays the monthly percentage of depression symptoms during COVID‐19 among long‐stay nursing home residents with ADRD.

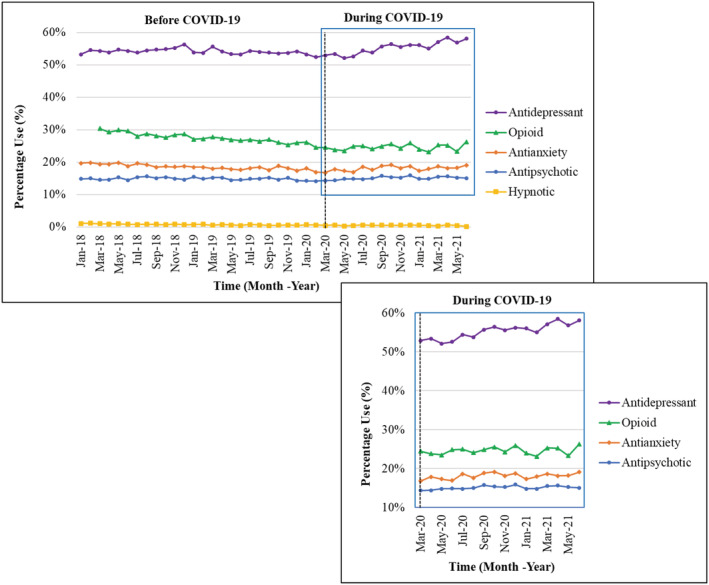

The change in slope comparing during‐COVID‐19 and pre‐COVID‐19 was positive for several CNS‐active medication classes (indicating an increase in use during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19): antidepressants (slope change = 0.41, p < 0.001), antianxiety (slope change = 0.17, p < 0.001), antipsychotics (slope change = 0.07, p < 0.05), and opioids (slope change = 0.24, p < 0.001) (Table 3 and Figure 2). The observed monthly prevalence in CNS‐active medication use from before the pandemic (i.e., February 2020) to study endpoint (i.e., June 2021), increased for antidepressants (52.4% vs 58.0%, 5.6% absolute change), opioids (24.5% vs 26.3%, 1.8% absolute change), antianxiety (16.9% vs 19.1%, 2.2% absolute change), and antipsychotics (14.2% vs 15.1%, 0.9% absolute change) (Table S3).

TABLE 3.

Interrupted time series analysis results for antidepressant, antipsychotic, antianxiety, hypnotic, and opioid medication use among long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias pre‐COVID‐19 and during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

| Antidepressant | Antipsychotic | Antianxiety | Hypnotic | Opioid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | Est. | 95% CI | |

| Period 1 (Jan 2018–Feb 2020): Pre‐COVID‐19 | ||||||||||

| % Use at beginning of period 1 (Jan 2018) | 54.6 | 15.1 | 19.6 | 1.0 | 29.7 | |||||

| Slope during pre‐COVID‐19 period | −0.04 | −0.08, −0.001* | −0.02 | −0.04, 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.10, −0.07** | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.01** | −0.19 | −0.21, −0.17** |

| Period 2 (Mar 2020–Jun 2021): during COVID‐19 | ||||||||||

| Slope during COVID‐19 period | 0.37 | 0.28, 0.45** | 0.05 | 0.01, 0.09* | 0.08 | 0.04, 0.13* | −0.01 |

−0.02, 0.01 |

0.04 | 0.001, 0.09* |

| Slope change pre‐ and during COVID‐19 | 0.41 | 0.31, 0.50** | 0.07 | 0.02, 0.12* | 0.17 | 0.13, 0.21** | 0.01 | −0.001, 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.19, 0.29** |

| % Use at end of period 2 (Jun 2021) | 58.0 | 15.5 | 18.7 | 0.4 | 24.6 | |||||

Note: Residents with diagnoses of Huntington's disease, Tourette syndrome, or schizophrenia were excluded. Prevalence reported in the predicted percent from the interrupted time series model.

Abbreviations: Est., estimate; 95% CI, 95% Confidence Interval.

p < .05.

p < 0.001.

FIGURE 2.

Antipsychotic, antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and opioid use among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD), January 1, 2018–June 30, 2021. The percentage of monthly medication [i.e., antidepressant, opioid, antianxiety, antipsychotic, and hypnotic] use was examined on all Minimum Data Set assessments per resident for a given month. Opioid medication use measurement started in March 2018. Residents with Huntington's disease, Tourette syndrome, and schizophrenia were excluded. Enlargement portrays the monthly percentage of antidepressant, opioid, antianxiety, and antipsychotic medication use during COVID‐19 among long‐stay nursing home residents with ADRD.

In contrast, the use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, opioids, antianxiety, and hypnotics was decreasing in the pre‐COVID‐19 period (Table 3). The use of hypnotics decreased overall, with no significant change in the rate of decrease during COVID‐19 compared to pre‐COVID‐19.

DISCUSSION

This study found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms and use of several CNS‐active medication classes increased among Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD during the COVID‐19 pandemic as compared to pre‐pandemic. However, a corresponding rise in behavioral symptoms in Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD was not observed. For some of our medication classes, although the increase during COVID‐19 was statistically significant, the absolute change was small.

Compared to our prior work which reported only the initial 4 months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, CNS‐active medication use patterns over the longer period in this study showed change among long‐stay NH residents with ADRD in Michigan. 14 Specifically, we found an increase in the use of antipsychotic and antianxiety medications in Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD that was not observed in the 4 months after the start of the COVID‐19 pandemic. 14 Our results also showed an increase in both antidepressant and opioid use among Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD during COVID‐19 similar to our previous study. 14 Our results are consistent with two population‐based cohort studies in Canada using administrative data which found that antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, opioids and trazodone use increased in NH residents with ADRD during the pandemic compared to pre‐pandemic. 18 , 19

Although measures restricting visitation and limiting group and communal activities in NH were put in place to protect residents, they may have had unintended consequences of worsening depression or anxiety as evidenced by our finding of an increase in depressive symptoms. This increase in depression symptoms may be related the lack of regular interaction with their informal caregivers, increased loneliness, and social isolation. 20 , 21 A scoping review found that social connection is potentially related to mental health outcomes in long‐term care residents; however, there are wide definitions of social connection (e.g., social support, engagement, and loneliness) and variation among study designs. 22 Potentially low‐cost strategies identified to support social connection during the COVID‐19 pandemic included non‐pharmacological options such as addressing sensory deficits (e.g., vision and hearing loss), promoting sleep–wake cycles, incorporating art, music, or storytelling activities, exercising, visiting with pets, and reminiscing about prior events, people, or places. 22 Remotely delivered interventions, such as video calls with family members, may be an additional method to decrease social isolation and depression symptoms among NH residents with ADRD during pandemics. 23 , 24 , 25 However, shortages of NH staff, limitations on gathering in groups, or facility resources to purchase tablets or other technology may limit the implementation of activities to increase social connectedness during pandemics.

Beyond social interaction, informal caregivers support the needs of their care partner, providing some relief to nursing home staff. An analysis of Health and Retirement Study data indicated that over 70% of nursing home residents that needed help received that help from their informal caregivers. 26 The informal caregivers provided help with needs related to mobility (e.g., getting out of bed or across a room), self‐care (e.g., eating, bathing, toileting, and dressing), household activities (e.g., making meals), and medication use. 26 Informal caregivers may have also experienced their own distress related to changes in care in their care partner with dementia. 27 An analysis of sentiments from social media indicated increased emotional distress, such as depression, loneliness, and stress, among family caregivers of patients with dementia. 28

This study has several limitations. Our cohort only includes Michigan NHs and our results may not generalize to NH residents nationally. Next, we used the ARBS score to examine behavioral symptoms which does not include the full range of behavioral symptoms patients with ADRD may experience (e.g., apathy, insomnia) and we are limited to the medications captured on the MDS assessment. We did not assess differences in outcomes based on dementia severity or functional status and small differences may be significant because of the large sample size. This study does not follow longitudinal changes in individual NH residents over time. We tracked monthly outcomes within facilities which represents a subset of NH residents who had an eligible assessment within a given month. There is potential for the characteristics of the NH population to change during COVID‐19 (e.g., younger residents, higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity) as well as potential pandemic‐related changes in the quality of coding due to relaxation MDS assessment timing. Lastly, we did not account for policy and ecologic changes (e.g., visitation restrictions, community COVID transmission rates) that occurred over the study time period. Future studies should examine the impact of such changes (e.g., lifting of visitor restrictions) and the potential impact on behaviors and medication use.

In summary, Michigan long‐stay NH residents with ADRD had a higher prevalence of depression symptoms and CNS‐active medication use (i.e., antidepressant, antipsychotic, antianxiety, and opioid medications) during the COVID‐19 pandemic than before. Given these increased rates of medication use observed during the pandemic, careful consideration should be given to whether these medications need to be continued and efforts made for gradual dose reduction, as appropriate. Policies that increase social isolation and reduce social contact should be embarked upon with caution or with counterbalancing interventions to reduce the negative impacts on NH residents with ADRD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Antoinette B. Coe, Lauren B. Gerlach, Theresa I. Shireman, Julie P.W. Bynum. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Antoinette B. Coe, Lauren B. Gerlach. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Pil S. Park. Obtaining funding: Theresa I. Shireman, Julie P.W. Bynum. Administrative, technical, or material support: Julie P.W. Bynum. Supervision: Antoinette B. Coe, Lauren B. Gerlach.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors had no potential financial or personal conflicts of interest.

SPONSOR'S ROLE

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (P01 P01AG027296‐13). ABC (K08 AG071856) and LBG (K23 AG066864) are supported by the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supporting information

Table S1. International classification of diseases—clinical modification—10th revision (ICD‐CM‐10) codes used to identify Alzheimer's disease and related dementias

Table S2. Observed percentage of behavioral symptoms (Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale [ARBS] ≥ 1) and depression symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 [PHQ‐9] ≥ 10, indicating at least moderate depression) among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, January 2018–June 2021.

Table S3. Observed percentage of antipsychotic, antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and opioid medication use among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, January 2018–June 2021.

Coe AB, Montoya A, Chang C‐H, et al. Behavioral symptoms, depression symptoms, and medication use in Michigan nursing home residents with dementia during COVID‐19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;1‐9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18116

This research was presented at the American Geriatrics Society 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting, Orlando, Florida, May 12, 2022.

Funding information National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: K08 AG071856, K23 AG066864, P01 P01AG027296‐13

REFERENCES

- 1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS announces new measures to protect nursing home residents from COVID‐19. May 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-new-measures-protect-nursing-home-residents-covid-19. Accessed April 20, 2022.

- 2. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Guidance for infection control and prevention of Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) in nursing homes (revised). March 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/qso-20-14-nh-revised.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2022.

- 3. Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Executive Order 2020–07: Temporary restrictions on entry into health care facilities, residential care facilities, congregate care facilities, and juvenile justice facilities—rescinded. March 14, 2020. Available at: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/state-orders-and-directives/2020/03/14/executive-order-2020-7. Accessed May 2, 2022.

- 4. Jones K, Mantey J, Washer L, et al. When planning meets reality: COVID‐19 interpandemic survey of Michigan nursing homes. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(11):1343‐1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibson DM, Greene J. State actions and shortages of personal protective equipment and staff in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(12):2721‐2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levere M, Rowan P, Wysocki A. The adverse effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on nursing home resident well‐being. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(5):948‐954.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gilstrap L, Zhou W, Alsan M, Nanda A, Skinner JS. Trends in mortality rates among Medicare enrollees with Alzheimer disease and related dementias before and during the early phase of the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(4):342‐348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu KY, Howard R, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia wellbeing and COVID‐19: review and expert consensus on current research and knowledge gaps. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(11):1597‐1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown EE, Kumar S, Rajji TK, Pollock BG, Mulsant BH. Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(7):712‐721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, et al. Point and 5‐year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170‐177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Geriatrics Society American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry . Consensus statement on improving the quality of mental health care in U.S. nursing homes: management of depression and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(9):1287‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellis ML, Molinari V, Dobbs D, Smith K, Hyer K. Assessing approaches and barriers to reduce antipsychotic drug use in Florida nursing homes. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(6):507‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerlach LB, Park PS, Shireman TI, Bynum JPW. Changes in medication use among long‐stay residents with dementia in Michigan during the pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(7):1743‐1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Long‐Term Care Facility Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) 3.0 User's Manual. Version 1.17.1. 2019. Available at: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/mds-3.0-rai-manual-v1.17.1_october_2019.pdf. Accessed April 23, 2021.

- 16. McCreedy E, Ogarek JA, Thomas KS, Mor V. The minimum data set agitated and reactive behavior scale: measuring behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1548‐1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bélanger E, Thomas KS, Jones RN, Epstein‐Lubow G, Mor V. Measurement validity of the Patient‐Health Questionnaire‐9 in US nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(5):700‐708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maxwell CJ, Campitelli MA, Cotton CA, et al. Greater opioid use among nursing home residents in Ontario, Canada during the first 2 waves of the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(6):936‐941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Campitelli MA, Bronskill SE, Maclagan LC, et al. Comparison of medication prescribing before and after the COVID‐19 pandemic among nursing home residents in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2118441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holaday LW, Oladele CR, Miller SM, Dueñas MI, Roy B, Ross JS. Loneliness, sadness, and feelings of social disconnection in older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(2):329‐340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Simard J, Volicer L. Loneliness and isolation in long‐term care and the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):966‐967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bethell J, Aelick K, Babineau J, et al. Social connection in long‐term care homes: a scoping review of published research on the mental health impacts and potential strategies during COVID‐19. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):228‐37.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gorenko JA, Moran C, Flynn M, Dobson K, Konnert C. Social isolation and psychological distress among older adults related to COVID‐19: a narrative review of remotely‐delivered interventions and recommendations. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(1):3‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sävenstedt S, Brulin C, Sandman PO. Family members' narrated experiences of communicating via video‐phone with patients with dementia staying at a nursing home. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(4):216‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Padala SP, Jendro AM, Orr LC. Facetime to reduce behavioral problems in a nursing home resident with Alzheimer's dementia during COVID‐19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:113028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coe NB, Werner RM. Informal caregivers provide considerable front‐line support in residential care facilities and nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(1):105‐111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borg C, Rouch I, Pongan E, et al. Mental health of people with dementia during COVID‐19 pandemic: what have we learned from the first wave? J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(4):1531‐1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoon S, Broadwell P, Alcantara C, et al. Analyzing topics and sentiments from twitter to gain insights to refine interventions for family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD) during COVID‐19 pandemic. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022;289:170‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. International classification of diseases—clinical modification—10th revision (ICD‐CM‐10) codes used to identify Alzheimer's disease and related dementias

Table S2. Observed percentage of behavioral symptoms (Agitated Reactive Behavior Scale [ARBS] ≥ 1) and depression symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 [PHQ‐9] ≥ 10, indicating at least moderate depression) among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, January 2018–June 2021.

Table S3. Observed percentage of antipsychotic, antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and opioid medication use among Michigan long‐stay nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, January 2018–June 2021.