Abstract

COVID‐19 outbreak and the measures needed to contain its first wave of contagion produced broad changes in citizens' daily lives, routines, and social opportunities, putting their environmental mastery and purpose of life at risk. However, these measures produced different impacts across citizens and communities. Building on this, the present study addresses citizens' understanding of the rationale for COVID‐19‐related protective measures and their perception of their own and their community's resilience as protective dimensions to unravel the selective effect of nationwide lockdown orders. An online questionnaire was administered to Italian citizens during Italian nationwide lockdown. Two moderation models were performed using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) path analysis. The results show that the understanding of the rationale for lockdown only associated with citizens' purpose of life and that it represented a risk factor rather than a protective one. Furthermore, the interaction effects were significant only when community resilience was involved. That is, personal resilience did not show the expected moderation effect, while community resilience did. However, the latter varied between being either full or partial depending on the dependent variable. In light of the above, the theoretical and practical implications of these results will be discussed.

Keywords: community resilience, COVID‐19, environmental mastery, lockdown, pandemic, personal resilience, purpose of life

1. INTRODUCTION

In the first months of 2020, communities and individuals all over the world have been impacted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020). As an attempt to contain the spread of the virus and reduce the infections, lots of countries adopted several protective measures. In Italy, which is the country where the present study was carried out, a nationwide lockdown was issued in the first days of March (Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri, 2020) and was partially eased on 4th May, according to the infection trend, as an attempt to slow down the first wave of contagions.

Overall, lockdown experience has been defined a syndemic (Horton, 2020) and a cultural trauma (Demertzis & Eyerman, 2020) as an attempt to adequately address its broad impact over all aspects of individuals' and communities' lives (e.g., Arcidiacono et al., 2022). Indeed, even though stay‐at‐home orders proved their effectiveness, they represented an unprecedented and unexpected experience for individuals, who experienced the loss of the daily landmarks and structures of meaning that defined their daily and future paths, as well as their understanding of the meaningfulness of their life paths and daily events, due to the disruptive changes implied by the restrictions (De Vincenzo et al., 2022; Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Horton, 2020; Procentese, Esposito, et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). Such unprecedented and prolonged restrictions brought about worries for current circumstances, discouragement, broad confusion and disorientation, lack of hope, and higher rates of stress and fear about the future among citizens (Di Napoli et al., 2021; Pancani et al., 2021; Salari et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020; Varga et al., 2021), who felt no more able to figure their future selves and lives in a clear way due to the emergency and to the uncertainties it brought about.

Altogether, lockdown orders threatened individuals' feelings about their ability to understand their life and its purpose and manage their restricted surrounding environment (Danioni et al., 2021; Gaboardi et al., 2022; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). Indeed, stay‐at‐home orders required citizens to look for different, adaptive meanings in order to make sense of such an unprecedented experience, which was out of their control, in order to reduce their feelings about their life as lacking meaning and a clear purpose (Demertzis & Eyerman, 2020; Marzana et al., 2021; Procentese, Esposito, et al., 2021). Furthermore, individuals also had to look for different landmarks that could help them manage their daily routines and environments after losing the chance to experience several usual places and activities outside their houses (Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). That is, lockdown experience endangered citizens' environmental mastery and purpose of life (Ryff, 1989b; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ryff & Singer, 2008), providing them with spontaneous liminal experiences (Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021), that is, moments requiring to adopt different ways of framing their live events (Greco & Stenner, 2017).

However, some resilient and adaptive reactions aimed at coping with the restrictions and grabbing the possibilities they brought about emerged too (e.g., Asmundson et al., 2021; Gattino et al., 2022; Migliorini et al., 2021; Tamiolaki & Kalaitzaki, 2020), suggesting that individuals' ability to adjust to lockdown restrictions and cope with their negative impacts varied across individuals as well as communities depending on the available resources (Conversano et al., 2020; Danioni et al., 2021; Gattino et al., 2022; Pakenham et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). While few studies deepened the understanding of the factors potentially explaining this selective effect with reference to the COVID‐19 pandemic, the understanding of the rationale underlying stay‐at‐home orders was already reckoned as a factor able to lessen the negative impact of quarantine measures, that is, individual stay‐at‐home orders, during previous epidemics (Blendon et al., 2004; Brooks et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2008).

Therefore, the first aim of this study is to address this gap by testing whether an appropriate understanding of the rationale for nationwide stay‐at‐home orders, that is, understanding that they were aimed at protecting citizens, their families, and their whole communities, might have represented a protective factor for citizens' environmental mastery and purpose of life in the face of the sudden changes such orders brought about.

Furthermore, resilience was mentioned as a condition potentially accounting for the selective effect of stay‐at‐home orders on individual perspectives, cognitions, and emotions (Lenzo et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022), with studies also suggesting that inter‐individual differences may have depended on individual but also on contextual assets (Kimhi et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). Indeed, resilience can favour individuals' successful adaptation through supporting the maintenance of a good functioning in the face of challenging or threatening circumstances (Callegari et al., 2016). Building on this, the present study deepens whether individual and community resilience might have represented resources able to enhance the hypothesised protective role of the understanding of the rationale for lockdown. It is here hypothesised that the understanding of the rationale for lockdown was more likely to be associated with adaptive answers when individuals perceived themselves and their local community as able to bounce back from troubling circumstances. That is, the moderator role of both individual and community resilience will be tested too.

Neighbourhoods were taken into account as the local community of reference since they represent psychologically relevant daily local communities in most Italian cities (Bonnes et al., 1990; Gatti et al., 2022; Mannarini et al., 2006). Furthermore, with specific reference to the months of COVID‐19‐related lockdown, they became even more relevant territorial and relational landmarks in citizens' daily lives since they served as reorientation drivers, “that is, elements that could help citizens in reconstructing their identities in a familiar environment after the disorientation that has been brought about by the outburst of the COVID‐19 emergency and its unexpected consequences (e.g., the disruption of the meanings attached to home, places, relationships, and identity)” (Gatti & Procentese, 2021, p. 3). Indeed, under huge emergencies, the tie to the community and the identification with it become stronger under the feelings of “being all in this together” (Aresi et al., 2022; Di Napoli et al., 2021).

2. RESILIENCE AS A PROTECTIVE DIMENSION

Since the COVID‐19 pandemic represented an emergency involving entire communities and requiring community‐level management strategies too (Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022), both individual and community resilience require further attention with reference to it. Indeed, as far as being similar, they represent linked yet not overlapping constructs (Berkes & Ross, 2013; Pfefferbaum et al., 2008; Ungar, 2011). Personal resilience refers to individuals' “capacity to foster, engage in, and sustain positive relationships and to endure and recover from life stressors and social isolation” (Cacioppo et al., 2011, p. 44), while community resilience refers to a community's “ability to anticipate threat; limit negative effects; and respond, adapt, and grow when confronted with a threat” (Pfefferbaum et al., 2017, p. 104).

Therefore, resilience represents the ability that allows systems to adapt to new circumstances rather than an outcome itself (Norris et al., 2008). Indeed, resilient individuals and communities are able to engage in accessing the needed resources (Ungar, 2011) in order to keep their balance and functioning in the face of challenging or troubling circumstances (Sheerin et al., 2018). At the individual level, personal resilience implies higher levels of optimism, flexibility, and strength, as well as more chances to adopt adaptive coping strategies (Callegari et al., 2016), while community resilience seems able to lessen the negative impact of stressful circumstances (Chandra et al., 2010; Plough et al., 2011) and reduce the rates of distress (Lyons et al., 2016).

In this vein, resilience is here hypothesised as a characteristic that may have supported the protective role of the understanding of the rationale for lockdown orders, protecting their environmental mastery and purpose of life. Indeed, recent studies about resilience showed that it helped easing negative outcomes during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Giovannini et al., 2020; Lenzo et al., 2020; Migliorini et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2022; Roma et al., 2020) and promoted a more thoughtful attitude towards both the threats lockdown experience posed and the foreseen opportunities for personal growth it offered (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022).

3. THE STUDY: AIMS AND HYPOTHESES

The overall goal of the present study is to provide a first, tentative explanation of the selective effect (Prati & Mancini, 2021), which was observed with reference to the impact of stay‐at‐home orders and lockdown experiences on citizens' feelings that they were able to manage what happened in their surrounding environment and that their life was meaningful. Specifically, since this effect varied across individuals as well as across communities (Conversano et al., 2020; Danioni et al., 2021; Gattino et al., 2022; Pakenham et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022) and since the pandemic required a multi‐level management (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022), both individual and community‐related assets will be taken into account, consistently with recent suggestions (Kimhi et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). Altogether, two main aims will be addressed.

First, the role of individuals' understanding of the rationale underlying stay‐at‐home orders will be deepened. Indeed, such understanding already showed a protective role in individuals' well‐being and coping with quarantine measures, that is, individual stay‐at‐home orders, during previous epidemics (Blendon et al., 2004; Brooks et al., 2020; Reynolds et al., 2008). Consistently, the same protective role is hypothesised here in the face of collective stay‐at‐home orders:

individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown positively associates with their environmental mastery (H1a) and purpose of life (H1b).

Second, the role of individual and community resilience as factors supporting the protective role of individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown will be addressed too. Indeed, recent studies about the impact of lockdown measures suggested that resilience might have represented a condition potentially accounting for their selective effect (Lenzo et al., 2020; Prati & Mancini, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022) and that both personal and community ones might have been involved due to the multilevel management of the pandemic (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). Thus, the following hypotheses were added to the previous one:

personal resilience moderates the relationship of individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown with their environmental mastery (H2a) and purpose of life (H2b), that is, the higher the personal resilience, the stronger both these positive relationships.

community resilience moderates the relationship of individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown with their environmental mastery (H3a) and purpose of life (H3b), that is, the higher the community resilience the stronger both these positive relationships.

4. METHOD

4.1. Participants and procedures

Three hundred and fifty Italian citizens took part in the study. Data were collected in Italy between March and April 2020, that is, during the months of most tight lockdown and social distancing measures due to the COVID‐19 outbreak. In compliance with COVID‐19‐related safety standards, the questionnaire was shared through Facebook and online word of mouth, using snowball sampling procedures. Participants received no compensation for participating in the study. The questionnaire was introduced with an explanation of confidentiality issues, where participants had to express their informed consent by ticking a box to take part in the study. No IP addresses or identifying data were retained.

The participants (27.1% males) were aged between 18 and 72 (M = 33.62; SD = 12.42), with 87.4% of them aged under 50. Consistently with the age range, 34% had a high school diploma, 22.9% had a bachelor's degree, 25.1% had a master's degree, 11.1% had a post‐graduate degree title, and only 6.3% and 0.6% had, respectively, a secondary school diploma and a primary school diploma. As of their work, 38% were students, 16.9% were subordinate workers, 14.9% were unemployed, 13.4% were freelancers, and 13.4% were employees, while only 1.7% and 1.1%, respectively, had managerial positions or were business owners; 0.6% were retirees.

Of the participants, 39.1% were unmarried and 34.6% were married or cohabitant, 22.3% were in a couple relationship but did not live with their partner, and only 2.9% and 1.1% were separated or divorced and widower, respectively. Most of the participants stated no one in their family had contact with COVID‐19‐infected individuals due to their work (67.4%) nor had been infected by COVID‐19 themself (96.6%); 56% did not know anyone infected with COVID‐19 at all. Consistently, 95.1% of the participants said no one in their family recovered after having been infected by COVID‐19, and 60.9% said they did not know people who had recovered from COVID‐19.

4.2. Measures

The questionnaire included a socio‐demographic section, followed by these specific measures.

4.2.1. Understanding of the rationale for lockdown

The items about the understanding of the rationale for quarantine (3 items) by Reynolds et al. (2008) were adapted to lockdown experience (e.g., “Lockdown protects self”) and used with a 5‐point Likert scale response set (1 = Strongly disagree; 5 = Strongly agree).

4.2.2. Personal resilience

The 10‐item version of the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC; Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007) was used to detect respondents' perceptions of personal resilience. Respondents were asked to rate how much the content of each item (e.g., “Able to adapt to change”) was true for them on a 4‐point Likert scale (1 = Not true at all; 4 = True nearly all of the time).

4.2.3. Community resilience

The Fletcher–Lyons Collective Resilience Scale (FLCRS, 5 items, Lyons et al., 2016) was used with reference to respondents' neighbourhoods. They were asked to rate their agreement with each item (e.g., “My community bounces back from even the most difficult setbacks”) on a 7‐point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree).

4.2.4. Environmental mastery and purpose of life

The environmental mastery (7 items, for example, “I am good at juggling my time so that I can fit everything in that needs to be done,” “I have difficulty arranging my life in a way that is satisfying to me” [reverse scored item]) and purpose of life (7 items, for example, “I enjoy making plans for the future and working to make them a reality,” “I used to set goals for myself, but that now seems a waste of time” [reverse scored item]) items from Ryff's 42‐item Psychological Well‐Being Scale (Ryff, 1989a, 1989b) were used. Respondents were asked to rate their agreement with each item on a 6‐point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 6 = Strongly agree).

4.3. Data analysis

4.3.1. Preliminary analyses

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were run with structural equation modelling (SEM) to test the factor structure for each measure. To evaluate the model fit, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Standardised Root Mean square Residual (SRMR) were observed (MacCallum & Austin, 2000). For CFI, values equal to or greater than .90 and .95, respectively, reflect good or excellent fit indices; for SRMR, values equal to or smaller than .06 and .08, respectively, reflect good or reasonable fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The reliability was checked through Cronbach's alphas (α).

As to environmental mastery, one item (“I often feel overwhelmed by my responsibilities”) significantly lowered its Cronbach's alpha. Thus, in addition to the above‐mentioned fit indices, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) were observed too in order to define whether to include this item in the subsequent analyses. Both of these indices suggest which model has the best fit among different ones; for both, the lower the value, the better the fit.

4.3.2. Hypothesis testing

To address all the hypotheses, two moderation models were performed using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) path analysis: each model had the understanding of the rationale for lockdown as the independent variable and individual and community resilience as the moderators, while the dependent variables were environmental mastery in one model and purpose of life in the other. The independent and moderator variables were centred before entering them in the models. Before testing the hypotheses, the absence of outliers and influential cases was checked using the leverage value and Cook's D (Cousineau & Chartier, 2010). To witness the absence of such values, leverage values should always be lower than 0.2 and Cook's D should always be lower than 1. A bootstrap estimation approach with 10,000 samples was used to test the significance of the results (Hayes, 2018). The bias‐corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed by determining the effects at the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles; the effects are significant when 0 is not included in the CI.

To facilitate the interpretation of the significant interaction effects, the Johnson–Neyman technique (Johnson & Neyman, 1936) was used, as it locates the regions of the moderator where the effect of the dependent variable on the outcome is significant (Preacher et al., 2006, 2007). The regions of significance are those wherein 0 is not included between the upper and lower confidence bands, that is, the 95% CI for the plotted slope (Bauer & Curran, 2005; Preacher et al., 2006).

5. RESULTS

5.1. Preliminary results

Reliability and fit indices, descriptive statistics, and correlations for all the study variables are in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of model fit and reliability indices, descriptive statistics, and correlations for all the measures

| Variables | α | CFI | SRMR | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Understanding of the rationale for lockdown | .96 | .99 | .001 | 3.95 b | 1.09 | ‐ | |||

| 2. Personal resilience | .89 | .92 | .04 | 2.96 c | 0.62 | .327*** | ‐ | ||

| 3. Community resilience | .96 | .98 | .01 | 3.70 d | 1.58 | .258*** | .437*** | ‐ | |

| 4. Environmental mastery a | .70 | .99 | .03 | 4.12 e | 0.95 | .326*** | .501*** | .302 | ‐ |

| 5. Purpose of life | .70 | .99 | .02 | 4.27 e | 0.92 | .086 | .369*** | .159** | .478*** |

Note: n = 350. ***p < .001 (2‐tailed); **p < .01 (2‐tailed).

Abbreviations: CFI, comparative fit index; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; SRMR, standardised root mean square residual; α, Cronbach alpha.

The scores in the table are calculated without the deleted item.

1–5 range scale.

1–4 range scale.

1–7 range scale.

1–6 range scale.

The item “I often feel overwhelmed by my responsibilities” was removed from the pool detecting environmental mastery as it significantly lowered Cronbach's alpha (which was .62 with the item, while .70 without it) and worsened all the fit indices for the scale (with the item: CFI = .96, SRMR = 0.08, AIC = 8,172.06, and BIC = 8,264.65; without the item: CFI = .99, SRMR = 0.03, AIC = 6,951.62, and BIC = 7,024.92).

5.2. Hypothesis testing

The leverage value was always lower than 0.04 in both models, while Cook's D lowest and highest values were 0 and 0.11 for the first model and 0 and 0.06 for the second one. Overall, these results indicate there were no significant values affecting the analyses.

The performed models only partially confirmed the hypotheses (see Table 2). Indeed, the understanding of the rationale for lockdown showed a significant, yet negative, effect on individuals' purpose of life but not on their environmental mastery. That is, H1 was not confirmed. Furthermore, personal resilience showed no moderation effects, mismatching H2. Differently, community resilience showed moderate effects on both the hypothesised relationships, yet its effect varied depending on the considered relationship.

TABLE 2.

Conditional effects

| Predictors | Dependent variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental mastery | Purpose of life | |||

| B (SE) | 95% CI | B (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Understanding of the rationale for lockdown | 0.19 (0.20) | (−0.18, 0.60) | −0.65*** (0.20) | (−1.02, −0.31) |

| Personal resilience | 1.03*** (0.30) | (0.44, 1.51) | 0.03 (0.31) | (−0.57, 0.64) |

| Community resilience | −0.21 (0.14) | (−0.50, 0.005) | −0.23 (0.13) | (−0.50, 0.02) |

| Understanding of the rationale for lockdown x personal resilience | −0.09 (0.07) | (−0.24, 0.03) | 0.14 (0.08) | (−0.02, 0.28) |

| Understanding of the rationale for lockdown x community resilience | 0.06* (0.03) | (0.004, 0.12) | 0.06* (0.03) | (0.004, 0.11) |

| Variance explained (%) | 29.7 | 17.4 | ||

Note: n = 350. The predictor and the two moderators are always centred. ***p < .001 (2‐tailed); **p < .01 (2‐tailed); *p < .05 (2‐tailed).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

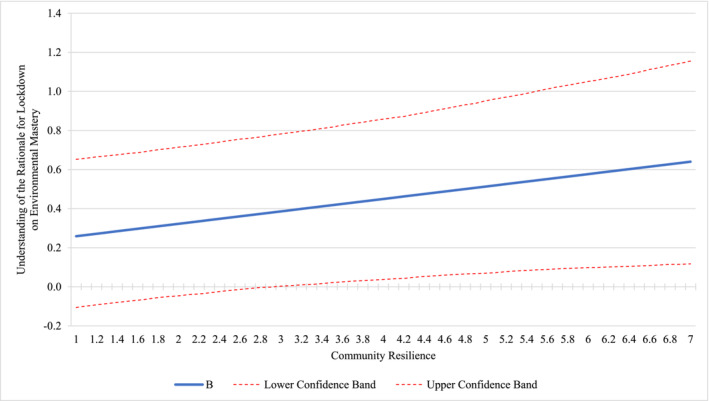

The Johnson–Neyman technique showed that the relationship between individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown and their environmental mastery became significant and positive when their community resilience had values higher than 3 (see Figure 1), B = 0.39, p < .05, 95% CI [0.003, 0.78]. That is, when community resilience was rated equal to or higher than 3, individuals' environmental mastery increased as their understanding of the rationale for lockdown did, and the strength of this positive relationship increased as community resilience did, supporting H3a.

FIGURE 1.

Interaction effect of community resilience and individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown on their environmental mastery. n = 350. Unstandardised coefficients (B) for the slope and their confidence bands are shown. The predictor and the moderator are centred

Conversely, when the dependent variable was individuals' purpose of life, its relationship with the predictor was significant yet negative when community resilience had values lower than 3.2 (see Figure 2), B = −0.46, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.92, −0.005]. That is, when community resilience was rated as equal to or lower than 3.2, individuals' purpose of life decreased as their understanding of the rationale for lockdown did, and the strength of this relationship increased as community resilience decreased, mismatching H3b.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction effect of community resilience and individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown on their purpose of life. n = 350. Unstandardised coefficients (B) for the slope and their confidence bands are shown. The predictor and the moderator are centred

6. DISCUSSION

The present study aimed at deepening the selective effect of COVID‐19‐related lockdown measures by testing the protective role of the understanding of the rationale underlying them with specific reference to individuals' environmental mastery and purpose of life. Indeed, such dimensions emerged as especially at risk due to the peculiarities of such stay‐at‐home orders, which configured as sudden, unexpected, unprepared, and unprecedented for individuals and communities and impacted all the fields of their daily lives (Demertzis & Eyerman, 2020; Marzana et al., 2021; Procentese, Esposito, et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). Furthermore, this study took into account the role of individual and community resilience as two conditions that could favour such a protective role by enhancing the hypothesised positive relationships, that is, it tested their moderator roles.

Overall, the protective role of the understanding of the rationale underlying COVID‐19‐related lockdown was not confirmed since it showed no relationship with individuals' environmental mastery and a negative association with their purpose of life. These results suggest that during the COVID‐19 pandemic the understanding of the rationale underlying the measures needed to contain the spread of the contagion did not play the protective role it played during previous sanitary emergencies (e.g., Blendon et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2008) in the face of the sense of bewilderment and the need to give new meanings to previous habits and activities, as well as to reorganise their daily routines according to the different time and space availability, which all stemmed from lockdown and pandemic experiences (Danioni et al., 2021; Di Napoli et al., 2021; Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Procentese, Esposito, et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). That is, individuals may have felt no more able to effectively use the surrounding opportunities, which had been frozen by stay‐at‐home orders, and to select or create contexts consistent with their needs and values due to the lockdown itself and not to an improper or none understanding of the rationale for such orders.

In addition, these results suggest that understanding the need for lockdown orders may have made citizens feel their lives lacked a clear direction and purpose. This may have depended on the pandemic impacting the stability of individuals' daily routines, frames of meaning, relational habits, and ways of experiencing the surrounding world (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). Individuals experienced the loss, fragmentation, or failure of the previously established meanings (De Vincenzo et al., 2022) as well as of their ability to understand and manage their daily reality and surrounding environments (Danioni et al., 2021) in the face of such unprecedented event: they had to reshape their present and future plans to be seamless with their past, due to the uncertainty the pandemic and prolonged stay‐at‐home orders with no clear deadline brought about, that is, due to some events out of their and everyone else's control, which could have made them feel that their past life had been interrupted. In this vein, they often focused on current activities as an attempt not to think about the unpredictability of the present and near future due to the pandemic (Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021). Altogether, understanding that an external order freezing their daily routines and planned projects was needed to safeguard their and others' safety and health due to the broad impact of the pandemic worldwide may have made them feel like they had lost the sense of what they were trying to accomplish in life (Ryff & Singer, 2008) and developed the feeling that what happened in their lives did not depend on their own behaviours, but rather on external forces and surrounding circumstances (De Vincenzo et al., 2022).

As to resilience as a condition supporting the adaptation to lockdown orders, personal resilience did not confirm its role either. However, consistently with previous literature framing it as individuals' ability to preserve an adaptive functioning under challenging circumstances building on the resources they can activate, as well as their optimism, flexibility, and adaptive coping strategies (Cacioppo et al., 2011; Callegari et al., 2016; Sheerin et al., 2018; Ungar, 2011), it showed a protective effect as to individuals' environmental mastery. Overall, these results supported previous suggestions about personal resilience being able to lessen the negative impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on individuals' lives (Giovannini et al., 2020; Lenzo et al., 2020; Migliorini et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2022; Roma et al., 2020), even though they also suggested that it did not provide conditions facilitating the protective effect of other dimensions, such as the understanding of the rationale for lockdown. However, the lack of moderation of personal resilience may have also depended on citizens relying on intersubjective experiences more than on their own individual ones as anchors to find new stability and share new meanings (De Vincenzo et al., 2022; Gatti & Procentese, 2021) due to the pandemic representing a collective cultural trauma (Demertzis & Eyerman, 2020) as well as a syndemic (Arcidiacono et al., 2022; Horton, 2020).

In this vein, community collective resilience rather showed an impact on the relationships of the understanding of the rationale for lockdown orders with both environmental mastery and purpose of life, which in both cases became positive relationships. This may have depended on community resilience also implying an adequate information provision by community leaders (Norris et al., 2008; Pfefferbaum et al., 2013, 2014), which may have promoted a more correct understanding of the need for lockdown orders and, above all, of their effectiveness. Furthermore, it is important to mention that community resilience was here considered with reference to neighbourhood communities. Taken together, this supports previous results about neighbourhood playing a supportive role in citizens' reorientation as in the face of COVID‐19‐related disruptions (Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Pescaroli & Kelman, 2017), that is, helping them keeping the consistence and integrity of their identities and daily routines, as well as the perception of living in a familiar and manageable environment.

However, such a dimension represented a fully protective condition only when it came to environmental mastery; in that case, from average levels of community resilience onward, the relationship between this variable and individuals' understanding of the rationale for lockdown became positive and stronger. Differently, its protective potential was reduced when it came to the purpose of life. In fact, the higher the understanding of the rationale for lockdown, the higher the purpose of life, but this only worked down to average levels of community resilience; however, the relationship between these two variables became nonsignificant from average levels of community resilience onward. Overall, these results suggest that the role of neighbourhoods was different according to the dimension of individual experience that was taken into account. That is, neighbourhood community resilience showed a different moderating effect when it came to the relationship of the understanding of the rationale for lockdown measures with either community members' environmental mastery or purpose in life.

On the one hand, when it came to feelings of effectiveness in managing the surrounding environment, opportunities, and resources (that is, environmental mastery, Ryff & Singer, 2008), belonging to more resilient neighbourhoods favoured individuals in understanding the need for lockdown measures. This may have depended on community resilience being able to promote a more thoughtful attitude towards both the threats lockdown experience posed and the foreseen opportunities for personal growth it offered (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). Indeed, a thoughtful attitude may have allowed individuals to understand the actual sources and implications of the lack of control they perceived, as well as to clearly detect the links to the pandemic (Gattino et al., 2022). Furthermore, it is to mention that community resilience also associates with increased local support and resources (Norris et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2017; Ungar, 2011), which can help mitigating the negative impact of stressful or challenging circumstances at both individual and community levels (Chandra et al., 2010; Plough et al., 2011).

However, on the other hand, when it came to the feeling about one's life having direction, continuity, and purpose (that is, the purpose of life, Ryff & Singer, 2008), community resilience only had a limited protective effect, since higher levels of it counteracted the protective effect of the understanding of the rationale for lockdown up to the point making its relationship with the purpose of life nonsignificant. Such an ambivalent role of community resilience with reference to the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on citizens' lives has already emerged from other recent studies (Mannarini et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). As a possible explanation for such results, Mannarini et al. (2021) emphasised that the effect of community resilience may be limited due to it requiring individuals to evaluate their community's instrumental capacity to manage emergencies and recover from them. Furthermore, Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al. (2022) underlined that such unexpected results may depend on community resilience, which is often conceptualised as the broad ability to face stressful circumstances at large – as it is in the FLCRS. Conversely, when respondents are asked to evaluate their community's resilience with reference to a specific, concrete disaster, its impact shapes differently (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022).

Taken together, what emerges echoes previous results about citizens experiencing a crisis of meanings (De Vincenzo et al., 2022; Procentese, Gatti, & Ceglie, 2021) despite their understanding of the rationale for lockdown measures. Indeed, during those months, they had to put all their previously established meanings and routines at stake and endeavour to identify new ones that could better explain the needed redefinition for social relationships, daily routines, cognitions, and emotions. These results specifically highlight the relevance of an adequate understanding of the need for such an extreme protective measure, as lockdown was, in order to avoid the latter to have deep negative consequences on individuals' understanding of their surrounding context, opportunities, and potential paths for growth (Gattino et al., 2022). Furthermore, this evidence stresses the meaningful role of the community of belonging in helping individuals adjust to the needed changes, which was already suggested with reference to other stages of the pandemic (Gatti & Procentese, 2021).

However, tightly linked to this, this study also corroborates recent evidence (Mannarini et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022) about the need for a deeper understanding of the role community resilience played during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and may consistently play during other future emergencies involving entire communities (Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022). That is, future studies are needed to better disentangle how community resilience works in this kind of circumstance, in order to understand whether it represents a protective dimension, as it has been hypothesised until now, or too high levels of it may rather have counterproductive effects, as it seems suggested by present and recent results, by promoting a less active and thoughtful attitude towards the ongoing circumstances and emergencies (Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022).

This study highlights the potential that communities have in safeguarding their members' opportunities for growth and personal development at large and in the face of emergencies and disasters more specifically (Gatti & Procentese, 2021; Gattino et al., 2022), suggesting the need for interventions aimed at building communities and strengthening people–communities relationships.

6.1. Limitations and future directions

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged too. First, memory bias and response fatigue should be taken into account due to the online administration of the questionnaire, and even more, considering that the latter happened during months in which citizens were locked into their houses and all their daily activities had moved online. Furthermore, snowball sampling implied a self‐selection bias and provided a nonrepresentative sample. Nevertheless, it is also to mention that these procedures allowed to deepen individuals' experiences in the very first stage of the pandemic, that is, during the nationwide lockdown which was enforced in the first months of the outbreak, by reaching a broad group of participants and gathering data while complying with the needed restraints.

Furthermore, the cross‐sectional design of the study allows to have a picture of individuals' experiences in that very time yet hinders from further inferences. That is, reversed relationships cannot be excluded based on these data; e.g., individuals with higher levels of environmental mastery and purpose of life might have better understood the rationale for lockdown measures due to their individual predisposition. Future studies should further look into these issues by adopting longitudinal designs.

Finally the ambiguous results about the role of community resilience in community members' lives should be further deepened too, since this study joins other recent ones (e.g., Mannarini et al., 2021; Procentese, Gatti, Rochira, et al., 2022) in suggesting that this issue requires more attention. Indeed, it should also be taken into account that some other variables which have not been considered yet may play a role in explaining the emerged relationships.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors declare that the research study is conducted ethically, responsibly, and legally; the results are reported honestly; the submitted work is original and not (self‐)plagiarised; funding sources and conflicts of interest are disclosed. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities of the University of Naples Federico II.

Procentese, F. , & Gatti, F. (2022). Environmental mastery and purpose of life during COVID‐19‐related lockdown: A study deepening the role of personal and community resilience. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 1–15. 10.1002/casp.2671

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Arcidiacono, C. , Caso, D. , Di Napoli, I. , Donizzetti, A. R. , & Procentese, F. (2022). Sindemia COVID 19 in un approccio di psicologia sociale e di comunità. Fattori di protezione e di rischio. TOPIC ‐ Temi Di Psicologia dell'Ordine Degli Psicologi Della Campania, 1(1), 1–14. 10.53240/topic001.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aresi, G. , Procentese, F. , Gattino, S. , Tzankova, I. , Gatti, F. , Compare, C. , … Guarino, A. (2022). Prosocial behaviours under collective quarantine conditions. A latent class analysis study during the 2020 COVID‐19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 32(3), 490–506. 10.1002/casp.2571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson, G. J. G. , Paluszek, M. M. , & Taylor, S. (2021). Real versus illusory personal growth in response to COVID‐19 pandemic stressors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 81, 102418. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, D. J. , & Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400. 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. , & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20. 10.1080/08941920.2012.736605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon, R. J. , Benson, J. M. , DesRoches, C. M. , Raleigh, E. , & Taylor‐Clark, K. (2004). The public's response to severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 38(7), 925–931. 10.1086/382355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnes, M. , Mannetti, L. , Secchiaroli, G. , & Tanucci, G. (1990). The city as a multi‐place system: An analysis of people‐urban environment transactions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 10(1), 37–65. 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80023-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K. , Webster, R. K. , Smith, L. E. , Woodland, L. , Wessely, S. , Greenberg, N. , & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of lockdown and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395, 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T. , Reis, H. T. , & Zautra, A. J. (2011). Social resilience: The value of social fitness with an application to the military. American Psychologist, 66(1), 43–51. 10.1037/a0021419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegari, C. , Bertù, L. , Lucano, M. , Ielmini, M. , Braggio, E. , & Vender, S. (2016). Reliability and validity of the Italian version of the 14‐item resilience scale. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 9, 277–284. 10.2147/PRBM.S115657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell‐Sills, L. , & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): Validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. 10.1002/jts.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A. , Acosta, J. D. , Meredith, L. S. , Sanches, K. , Howard, S. , Uscher‐Pines, L. , Williams, M. V. , & Yeung, D. (2010). Understanding community resilience in the context of national health security: A literature review. RAND Corporation. 10.7249/WR737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conversano, C. , Di Giuseppe, M. , Miccoli, M. , Ciacchini, R. , Gemignani, A. , & Orrù, G. (2020). Mindfulness, age and gender as protective factors against psychological distress during Covid‐19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1900. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau, D. , & Chartier, S. (2010). Outliers detection and treatment: A review. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 58–67. 10.21500/20112084.844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danioni, F. , Sorgente, A. , Barni, D. , Canzi, E. , Ferrari, L. , Ranieri, S. , … Lanz, M. (2021). Sense of coherence and COVID‐19: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Psychology, 155(7), 657–677. 10.1080/00223980.2021.1952151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vincenzo, C. , Serio, F. , Franceschi, A. , Barbagallo, S. , & Zamperini, A. (2022). A “viral epistolary” and psychosocial spirituality: Restoring transcendental meaning during COVID‐19 through a digital community letter‐writing project. Pastoral Psychology., 71, 153–171. 10.1007/s11089-021-00991-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demertzis, N. , & Eyerman, R. (2020). COVID‐19 as cultural trauma. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 8(3), 428–450. 10.1057/s41290-020-00112-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli, I. , Guidi, E. , Arcidiacono, C. , Esposito, C. , Marta, E. , Novara, C. , … Marzana, D. (2021). Italian community psychology in the COVID‐19 pandemic: Shared feelings and thoughts in the storytelling of university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 571257. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.571257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboardi, M. , Gatti, F. , Santinello, M. , Gandino, G. , Guazzini, A. , Guidi, E. , … Procentese, F. (2022). The photo diaries method to catch the daily experience of Italian university students during COVID‐19 lockdown. Community Psychology in Global Perspective, 8(2), 59–80. 10.1285/i24212113v8i2p59 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, F. , & Procentese, F. (2021). Local community experience as an anchor sustaining reorientation processes during COVID‐19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(8), 4385. 10.3390/su13084385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, F. , Procentese, F. , & Schouten, A. P. (2022). People‐nearby applications use and local community experiences: Disentangling their interplay through a multilevel, multiple informant approach. Media Psychology, 1–29. 10.1080/15213269.2022.2139272 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gattino, S. , Rizzo, M. , Gatti, F. , Compare, C. , Procentese, F. , Guarino, A. , … Albanesi, C. (2022). COVID‐19 in our lives: Sense of community, sense of community responsibility, and reflexivity in present concerns and perception of the future. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(5), 2344–2365. 10.1002/jcop.22780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, E. , Benczur, P. , Campolongo, F. , Cariboni, J. , & Manca, A. (2020). Time for transformative resilience: The COVID‐19 emergency. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. 10.2760/062495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greco, M. , & Stenner, P. (2017). From paradox to pattern shift: Conceptualising liminal hotspots and their affective dynamics. Theory & Psychology, 27(2), 147–166. 10.1177/0959354317693120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based perspective. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, R. (2020). Offline: COVID‐19 is not a pandemic. The Lancet, 396(10255), 874. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T. , & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P. O. , & Neyman, J. (1936). Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kimhi, S., Marciano, H., Eshel, Y., & Adini, B. (2020). Recovery from the COVID‐19 pandemic: Distress and resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101843. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lenzo, V. , Quattropani, M. C. , Musetti, A. , Zenesini, C. , Freda, M. F. , Lemmo, D. , … Franceschini, C. (2020). Resilience contributes to low emotional impact of the COVID‐19 outbreak among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 3062. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, A. , Fletcher, G. , & Bariola, E. (2016). Assessing the well‐being benefits of belonging to resilient groups and communities: Development and testing of the Fletcher‐Lyons collective resilience scale (FLCRS). Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 20(2), 65–77. 10.1037/gdn0000041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. C. , & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 201–226. 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarini, T. , Rizzo, M. , Brodsky, A. , Buckingham, S. , Zhao, J. , Rochira, A. , & Fedi, A. (2021). The potential of psychological connectedness: Mitigating the impacts of COVID‐19 through sense of community and community resilience. Journal of Community Psychology, 1‐17, 2273–2289. 10.1002/jcop.22775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarini, T. , Tartaglia, S. , Fedi, A. , & Greganti, K. (2006). Image of neighborhood, self‐image and sense of community. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26(3), 202–214. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marzana, D. , Novara, C. , De Piccoli, N. , Cardinali, P. , Migliorini, L. , Di Napoli, I. , … Procentese, F. (2021). Community dimensions and emotions in the era of COVID‐19. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 1‐16, 358–373. 10.1002/casp.2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini, L. , De Piccoli, N. , Cardinali, P. , Rollero, C. , Marzana, D. , Arcidiacono, C. , … Di Napoli, I. (2021). Contextual influences on Italian university students during the COVID‐19 lockdown: Emotional responses, coping strategies and resilience. Community Psychology in Global Perspective, 7(1), 71–87. 10.1285/i24212113v7i1p71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F. H. , Stevens, S. P. , Pfefferbaum, B. , Wyche, K. F. , & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1), 127–150. 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham, K. I. , Landi, G. , Boccolini, G. , Furlani, A. , Grandi, S. , & Tossani, E. (2020). The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 109–118. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancani, L. , Marinucci, M. , Aureli, N. , & Riva, P. (2021). Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1,006 Italians under COVID‐19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1540. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S. S. , Rogers, M. B. , Amlôt, R. , & Rubin, G. J. (2017). What do we mean by “community resilience”? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature. PLoS Currents, 9. 10.1371/currents.dis.db775aff25efc5ac4f0660ad9c9f7db2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescaroli, G. , & Kelman, I. (2017). How critical infrastructure orients international relief in cascading disasters. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 25(2), 56–67. 10.1111/1468-5973.12118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B. , & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the COVID‐19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B. J. , Reissman, D. B. , Pfefferbaum, R. L. , Klomp, R. W. , & Gurwitch, R. H. (2008). Building resilience to mass trauma events. In Sleet D., Mercy J., Bonzo S., & Doll L. (Eds.), Handbook of injury and violence prevention (pp. 347–358). Boston: Springer. 10.1007/978-0-387-29457-5_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, B. J. , Van Horn, R. L. , & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2017). A conceptual framework to enhance community resilience using social capital. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(2), 102–110. 10.1007/s10615-015-0556-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, R. L. , Pfefferbaum, B. , Nitiéma, P. , Houston, J. B. , & Van Horn, R. L. (2014). Assessing community resilience: An application of the expanded CART survey instrument with affiliated volunteer responders. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 181–199. 10.1177/0002764214550295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum, R. L. , Pfefferbaum, B. , Van Horn, R. L. , Klomp, R. W. , Norris, F. H. , & Reissman, D. B. (2013). The communities advancing resilience toolkit (CART): An intervention to build community resilience to disasters. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 19(3), 250–258. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318268aed8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plough, A. , Bristow, B. , Fielding, J. , Caldwell, S. , & Khan, S. (2011). Pandemics and health equity: Lessons learned from the H1N1 response in Los Angeles County. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 17(1), 20–27. 10.1097/phh.0b013e3181ff2ad7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati, G. , & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID‐19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta‐analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201–211. 10.1017/S0033291721000015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , Curran, P. J. , & Bauer, D. (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(3), 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , Rucker, D. D. , & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. 10.1080/00273170701341316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F. , Esposito, C. , Gonzalez Leone, F. , Agueli, B. , Arcidiacono, C. , Freda, M. F. , & Di Napoli, I. (2021). Psychological lockdown experiences: Downtime or an unexpected time for being? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1159. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.577089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F. , Gatti, F. , & Ceglie, E. (2021). Sensemaking processes during the first months of COVID‐19 pandemic: Using diaries to deepen how Italian youths experienced lockdown measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12569. 10.3390/ijerph182312569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F. , Gatti, F. , & Ceglie, E. (2022). Teachers' efficacy in the face of emergency remote teaching during COVID‐19 pandemic: The protective role of personal resilience and sense of responsible togetherness. Psicologia Sociale, 17(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Procentese, F. , Gatti, F. , Rochira, A. , Tzankova, I. , Di Napoli, I. , Albanesi, C. , … Marzana, D. (2022). The selective effect of lockdown experience on Citizens' perspectives: A multilevel, multiple informant approach to personal and community resilience during COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 1–22. 10.1002/casp.2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D. L. , Garay, J. R. , Deamond, S. L. , Moran, M. K. , Gold, W. , & Styra, R. (2008). Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiology & Infection, 136(7), 997–1007. 10.1017/S0950268807009156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma, P. , Monaro, M. , Colasanti, M. , Ricci, E. , Biondi, S. , Di Domenico, A. , … Mazza, C. (2020). A 2‐month follow‐up study of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID‐19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8180. 10.3390/ijerph17218180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989a). Beyond Ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35–55. 10.1177/016502548901200102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989b). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well‐being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. , & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well‐being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. , & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well‐being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. 10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N. , Hosseinian‐Far, A. , Jalali, R. , Vaisi‐Raygani, A. , Rasoulpoor, S. , Mohammadi, M. , … Khaledi‐Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 57. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheerin, C. M. , Lind, M. J. , Brown, E. A. , Gardner, C. O. , Kendler, K. S. , & Amstadter, A. B. (2018). The impact of resilience and subsequent stressful life events on MDD and GAD. Depression and Anxiety, 35, 140–147. 10.1002/da.22700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiolaki, A. , & Kalaitzaki, A. E. (2020). “That which does not kill us, makes us stronger”: COVID‐19 and posttraumatic growth. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113044. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torales, J. , O'Higgins, M. , Castaldelli‐Maia, J. M. , & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID‐19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. (2011). Community resilience for youth and families: Facilitative physical and social capital in contexts of adversity. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1742–1748. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varga, T. V. , Bu, F. , Dissing, A. S. , Elsenburg, L. K. , Bustamante, J. J. H. , Matta, J. , … Rod, N. H. (2021). Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and northern Europeans. The Lancet Regional Health ‐ Europe, 2, 100020. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID‐19 Outbreak. Retrieved from. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.