Abstract

Internal carotid artery dissection (ICAD) represents the cause of ictus cerebri in about 20% of all cases of cerebral infarction among the young adult population. ICAD could involve the extracranial and intracranial internal carotid artery (ICA). It could be spontaneous (SICAD) or traumatic (TICAD). It has been estimated that carotid injuries could complicate the 0,32% of cases of general blunt trauma and the percentage seems to be higher in cases of severe multiple traumas. TICAD is diagnosed when neurological symptoms have already occurred, and it could have devastating consequences, from permanent neurological impairment to death. Thus, even if it is a rare condition, a prompt diagnosis is essential. There are no specific guidelines regarding TICAD screening. Nevertheless, TICAD should be taken into consideration when a young adult or middle-aged patient presents after severe blunt trauma. Understanding which kind of traumatic event is most associated with TICAD could help clinicians to direct their diagnostic process. Herein, a review of the literature concerning TICAD has been carried out to highlight its correlation with specific traumatic events. TICAD is mostly correlated to motor vehicle accidents (94/227), specifically to car accidents (39/94), and to direct or indirect head and cervical trauma (76/227). As well, a case report is presented to discuss TICAD forensic implications.

Keywords: Internal carotid artery dissection, trauma, diagnostic screening, cervical trauma, neurological impairment, direct or indirect trauma

1. INTRODUCTION

Internal carotid artery dissection (ICAD) occurs when the blood penetrates the arterial wall because of a defect in the internal elastic lamina. The collection of blood between the tunica media and tunica adventitia could create a false lumen, also called pseudoaneurysm or false aneurysm. ICAD represents the cause of ictus cerebri in approximately 20% of cases of cerebral infarction among the young adult population [1, 2]. ICAD can be spontaneous (SICAD) or traumatic (TICAD). SICAD occurs in the absence of a traumatic event and usually correlates with genetic syndromes, recent infections, or specific risk factors (i.e., hypertension, migraine, and hypercholesterolemia). Conversely, TICAD follows a traumatic event. Both the extracranial and intracranial ICAs can be involved [3, 4]. Usually, a direct or indirect cervical injury is described, often correlating with motor vehicle accidents [5-8]. The need for diagnostic screening for TICAD in cases of head and/or cervical injury is controversial [9]. TICAD is often misdiagnosed or diagnosed when neurological symptoms have already occurred [9, 10]. As a consequence, significant and permanent neurological impairment can occur. For blunt carotid injuries, the morbidity rate is estimated to be as high as 80%, and the mortality rate is estimated to be as high as 40% [10-12]. Therefore, TICAD could have forensic consequences.

In this paper, a review of the literature concerning TICAD was carried out to highlight its correlation with specific traumatic events. In addition, its clinical and medico-legal implications are investigated through the presentation of a case report.

2. METHODS

The present systematic review was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review (PRISMA) standards [13]. A systematic literature search and a critical review of the collected studies were conducted. An electronic search of PubMed, Science Direct Scopus, Google Scholar, and Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) from database inception to November 2020 was performed. The search terms were “internal carotid artery”, dissection”, and “trauma” in the title, abstract, and keywords. The bibliographies of all located papers were examined and cross-referenced to identify relevant literature further. A methodological appraisal of each study was conducted according to the PRISMA standards, including an evaluation of bias. The data collection process included study selection and data extraction. Three researchers (RLR, PF, and MDP) independently examined the papers with titles or abstracts that appeared to be relevant and selected those that analysed traumatic internal carotid artery dissection with reference to Biffl type I, II, and III vascular injuries (intimal flap, dissection, and pseudoaneurysm) [14]. Disagreements concerning eligibility among the researchers were resolved by consensus. Preprint articles were excluded. Only papers in English were included in the research. Data extraction was performed by two investigators (AM, ACM) and verified by two other investigators (VF, ET). This study was exempted from institutional review board approval as it did not involve human subjects.

3. RESULTS

A review of the titles and abstracts as well as a manual search of the reference lists, were carried out. The reference lists of all identified articles were reviewed to find missed literature. This search identified 254 articles, which were then screened based on their abstracts. The resulting 128 reference lists were screened to exclude duplicates, which left 103 articles for further consideration. In addition, non-English papers were excluded, and the following inclusion criteria were used: (1) original research articles, (2) reviews and mini-reviews, and (3) case reports/series. These publications were carefully evaluated, taking into account the main aims of the review. This evaluation left 87 scientific papers comprising original research articles, case reports, and case series. Fig. (1) illustrates our search strategy.

Fig. (1).

An appraisal based on titles and abstracts as well as a hand search of reference lists was carried out. The resulting 254 references were screened to exclude duplicates, which left 128 articles for further consideration. These publications were carefully evaluated, taking into account the main aims of the review. This evaluation left 87 scientific papers comprising original research articles, case reports, and case series.

Table 1 summarizes all the studies published from 1990 to the present. The studies published before 1990 were excluded from Table 1 but are briefly described below. In a few cases, complete data extraction was not possible. However, the eligible data are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the literature regarding post-traumatic internal carotid artery dissection. Studies conducted before 1990 have been excluded.

| References | Number of Cases | Age | Sex | Type of Trauma | Presenting Neurological Symptoms | Trauma - Symptoms Interval | Before Diagnosis Imaging |

Type of ICA

Lesions |

Other Correlated Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al. 1991 | 3 | 15ys | M | MVA | Hemiparesis | - | CT, DUS, angiography | ICAD | - |

| 22ys | F | - | CT, angiography | ||||||

| 43ys | F | angiography | Bilateral ICAD | ||||||

| Romner et al 1994 | 2 | 26ys | M | Wrestling | Altered consciousness, dysphasia, hemiparesis | < 1 day | CT, TCD, angiography, SPECT | ICAD | - |

| 23ys | F | Fall from staircase | Some minutes | MCA infarct | |||||

| Achtereekte et al. 1994 | 1 | 48ys | 1 M | Bicycle accident (blunt head trauma) | Transient loss of consciousness, aphasia, concentration disturbances, short-term memory loss | < some hours | Skull CT, TCD, DUS, angiography | ICAD with saccular aneurysm | Hematoma and bruise of the frontal area; Right MCA blood flow decrease |

| Fletcher et al. 1995 | 1 | 31ys | 1 M | Jockey fall (jaw and neck injury) | Loss of consciousness (soon recovered), Horner’s syndrome | < some hours | Neck X-rays, head CT | Left ICAD with complete occlusion | Left MCA infarct, left vertebral artery occlusion |

| Horner’s syndrome, major convulsive seizure, aphasia, hemiplegia | 4 days | Head CT, angiography | |||||||

| Sanzone et al. 1995 | 2 | 27ys | 2 M | Assault with a lead pipe | Loss of consciousness, hemiplegia, fixed dilated left pupil | < 1 day | Facial X-rays, head CT, angiography |

ICA tapering | MCA and ACA infarct |

| 39ys | Hemiplegia and hemianopsia | 1 day | |||||||

| Lemmerling et al. 1996 | 1 | 50ys | 1 M | Car accident | Dysarthria, difficult swallowing and hypoglossal nerve dysfunction | < some hours | Neck CT, MRA | ICAD | - |

| Laitt et al. 1996 | 8 | 35.9ys (range 21-52) | 5 M, 3 F | MVA (6), assault (1), horse fall (1) | Hemiparesis or hemiplegia (8), dysphasia or aphasia (4) | 4 hours up to 75 days | Brain CT, angiography, MRI and MRA (1) | ICAD (7), ICA pseudoaneurysm (1) | Cerebral infarct (7) |

| Alimi et al. 1996 | 7 | 35.7ys (range 21-59) | 3 M, 4 F | MVA (6), cervical manipulation (1) | Hemiparesis (2), hemiplegia (2), aphasia (2), Horner’s syndrome (1), oculomotor disturbances (1), recurrent TIAs (1) | < some hours | CT (7), doppler arteriography (5), arteriography (2) | Unilateral ICAD (3) with controlateral thrombosis (2), bilateral ICAD (1), false aneurysm (2), tight stenosis (1) | Cerebral infarct or hypodense cerebral lesions (6) |

| Pica et al. 1996 | 1 | 31ys | F | Car accident (restrained passenger) | Right retroorbital headache, right-sided tongue deviation, dysarthria | 4 months | Head and neck CT, lumbar puncture, MRI and MRA | Right ICAD with intramural hematoma | ICA tortuosity |

| Sidhu et al. 1996 | 1 | 17mo | M | Soft palate injury | Seizures | 48 hours | MRI, MRA | ICAD | Soft palate abrasion; cerebral infarct |

| Duke et al. 1997 | 6 | 29.5ys (range 19-40) | 3 M, 3 F | MVA | Horner’s syndrome (1), hemiparesis (2), no symptoms (4) |

< 2 hours up to 5 days | Head CT, angiography | ICAD (3), ICA intimal flap (1), ICA pseudoaneurysm (3) | Cerebral infarcts (2) |

| Matsuura et al. 1997 | 1 | 20ys | 1 F | MVA (no seat belt) | Carotidynia, unilateral oculosympathetic paresis, unilateral loss of limbs sensation, hemiparesis | 3 days | Cervical spine X-rays (soon after the accident), arteriography | Right ICAD at C1 level with pseudoaneysysm | - |

| Vishteh et al. 1998 | 13 | 30,6ys (range 12-71) | 9 M, 4 F | Blunt trauma (11), gunshot (1), stab (1) | Hemiparesis (11), cranial nerve deficits (2), aphasia (2), Hornes’s syndrome (2), focal seizure (1) | within some hours or later after hospital discharge | Brain CT (11), brain MRI (3), angiography (all) | ICAD (9 cervical, 3 distal cervical and petrous, 3 cavernous, and 1 petrous segments), plus occlusion (7), dissecting aneurysm (6), and rupture with carotid-cavernous fistula formation (2) | Cerebral contusion (5), elevated intracranial pressure (4), basal cranial fractures (5), vertebral fracture (2) |

| Alimi et al. 1998 | 8 | 35,2ys (range 17-54) | 3 M, 5 F | MVA (6 in car, 4 of which with seatbelt fastened; 1 moped), stairway fall (1) | Neurological deficit (3) plus aphasia (1), unconsciousness (6), hemiplegia (2) | < some hours up to 13 days |

Brain CT, DUS (4), angiography | Bilateral ICAD (8), with or without stenosis, dilatation, or thrombosis | Unilateral cerebral infarction (5), bilateral cerebral infarction (3), plus haemorrhagic cerebral contusion (2) |

| Kumar et al. 1998 | 1 | 45ys | 1 M | Vomiting | hemiplegia, one eye loss of vision, slurred speech, a decrease of consciousness | About 18 hours | Head CT, DUS, brain MRI | Bilateral ICAD, one side with occlusion, other side only intimal flap | ACA and MCA’s infarct |

| Gouny et al. 1998 | 1 | 39ys | 1 M | Motorcycle accident | Unilateral anisocoria and mydriasis, hemiplegia | < some hours | Brain CT, cervical echography, MRI | Bilateral ICAD with bilateral thrombosis | - |

| Schievink et al. 1998 | 4 | 35ys (range 31-39) | 3 M, 1 F | Softball neck direct impact (2), car accidents (2) | None (only the softball cases are described) | - | Head CT, angiography | ICAD with intimal flap, aneurysm, maybe thrombosis | - |

| Monolateral ptosis and miosis (only the softball cases are described) | 3 days | DUS, MRA | ICAD | - | |||||

| Simionato et al. 1999 | 1 | 39ys | 1 M | Car accident (craniofacial trauma) | Hemiparesis | < some hours | Head CT and MRI, MRA, digital subtraction angiography | ICAD with aneurysm and obstruction | Fronto-insular and deep hemisphere infarct |

| Babovic et al. 2000 | 1 | 43ys | 1 F | Car accident (seatbelt fastened, airbag deployment) | Unilateral progressive visual loss | 10 days | Orbits CT, fundus oculi examination, head CT, head MRI and MRA | Bilateral ICAD with bilateral thrombus | Closed head injury and facial fractures; frontal lobe infarct |

| Duncan et al. 2000 | 1 | 39ys | 1 M | Car accident (seatbelt fastened, airbag deployment) | Hemiplegia | < some hours | Brain CT, angiography | Bilateral ICAD with thrombus in the right ICA | fibromuscular ICA dysplasia; parietal lobe infarct with later haemorrhage |

| Busch et al. 2000 | 1 | 27ys | 1 F | Motorcycle accident | Progressive loss of consciousness | Several hours | Brain CT, angiography | Bilateral ICAD | VAD; cerebral infarct |

| Hughes et al. 2000 | 7 | - | - | Severe blunt head trauma | None (incidental finding) | - | Cervical spine/brain MRI (6), angiography (1) | ICAD | - |

| Lee and Jensen 2000 | 1 | 43ys | 1 F | Bicycle ride (no fall or accident) | Acute headache | < some hours | - | Bilateral extracranial ICAD with bilateral hematomas and pseudoaneurysms and stenosis | bilateral poor disc and cup margins, small inferotemporal cotton-wool spot in the left eye |

| persistent headache, transient visual disturbances such as unilateral scotoma and “granular” vision, transient complete blindness, unilateral ptosis and anisocoria | 1 day | Head CT (normal at day 2), ophthalmoscopic examination (day 9), dilated funduscopic examination, MRI and MRA (day 11) | |||||||

| Malek et al. 2000 | 2 | 37ys | 2 F | Strangulation | Upper limbs weakness, leg numbness, and dysphasia |

- | - | ICAD | - |

| 44ys | MVA (whiplash injury) | Dysphasia, unilateral upper limb weakness and numbness |

|||||||

| Scavée et al. 2001 | 1 | 53ys | M | MVA | Neck pain and dizziness | 6 weeks | CT, angiography, MRI | ICA pseudoaneurysm with intramural thrombus | - |

| Windfuhr 2001 | 1 | 5ys | F | Pharynx penetrating injury | Oral bleeding and anemia | 9 days | Angiography | ICAD with aneurysm | 3 mm pharyngeal lesion |

| McNeil et al. 2002 | 1 | 18ys | M | Gunshot | Not appreciable (sedated) | - | Head, face, and cervical spine CT, angiography | ICA pseudoaneurysm | Distal embolic angular artery occlusion |

| Duane et al. 2002 | 2 | 31ys | F | Strangulation and stabbing attempt | Seizure, tongue deviation | 8 days | Neck CT, angiography | ICA pseudoaneurysm | peritonsillar abscess |

| 27ys | F | Gun shot | - | - | Head x-ray, angiography | ICA AVF with pseudoaneurysm | - | ||

| Blanco Pampin et al. 2002 | 2 | 19ys | M | Car accident | Confusion, speech difficulties, unilateral facial nerve paralysis, and unilateral hemiplegia |

48 hours | Head CT, DUS, angiography | ICAD with thrombosis | Neck bruise and cerebral infarct |

| - | - | 33ys | F | Hanging attempt | Loss of consciousness and unilateral hemiplegia | 6 hours | Head CT | ICAD | Neck bruise and cerebral infarct with C2 odontoid fracture |

| Men et al. 2003 | 1 | 48ys | M | MVA | - | Few weeks | Angiography | ICAD with AVF | - |

| Pary and Rodnitzky 2003 | 1 | 43ys | M | Taekwondo training | Headache, transient visual disturbances, unilateral hemisensory loss and hemiparesis, Wernicke’s aphasia | < some hours | Head CT, brain MRI, MRA | ICAD with hematoma | MCA infarct |

| Fusonie et al. 2004 | 1 | 37ys | M | Car accident | One upper limb weakness episodes | 15 years | Cervical MRI, MRA | ICA pseudoaneurysm | - |

| Fanelli et al. 2004 | 1 | 17ys | 1 M | Motorcycle accident | Hemiplegia and positive Babinski’s sign | < some hours | Head CT | Bilateral ICAD | Right hemisphere cerebral infarct |

| Payton et al. 2004 | 1 | 11ys | 1 M | Playing accident (hitting head or neck to a padded wall) | Dysarthria, lethargy, ocular deviation, hemiplegia | < some hours | Multiple X-rays, head and cervical spine CT, head MRI and MRA | Bilateral ICAD | - |

| Fateri et al. 2005 | 1 | 52ys | 1 M | Car accident | Altered consciousness, hemisyndrome | < some hours | Craniocervicalthoracic CT | ICAD with tight stenosis and luminal thrombosis | Cerebral arteries’ filling defects related to thromboembolic events |

| Clarot et al. 2005 | 2 | 38ys | 1 M | Attempted strangulation | Altered consciousness, bilateral Babinski’s sign, permanent eye elevation, bradycardia, and right hemiparesis |

Hospital admission (not known the time from the trauma) | Brain CT, DUS | Bilateral CAD with bilateral thrombus and right ICAD and ECAD | Neck ecchymosis and abrasions; cerebral infarct and subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| 42ys | 1 F | Headache | 2 days | DUS, brain CT | Bilateral CAD | - | |||

| Cohen et al. 2005 | 10 | 42.7ys (range 17-62) | 8 M, 2 F | Multiple (6) or cranio-cervical trauma (4), with penetrating injury (2) | Signs of ischaemic stroke, TIA, carotidynia, Horner’s syndrome | 4 hours uo to 19 days | Brain CT, angiography | ICAD | - |

| Cothren et al. 2005 | 46 | 32±2 ys | 65% M, 35% F | MVA, falls, skiing injuries |

Not specified, 38 patients asymptomatic, 8 patients symptomatic | - | Angiography | Pseudoaneurysm | - |

| Joo et al. 2005 | 4 | 28.5ys (range 19-38) | 4 M | Blunt trauma (3) | Limb weakness (2), none (1) | - | CT, MRI, arteriography | Extracranial ICA pseudoaneurysm | - |

| Stab wound (1) | Limb weakness, pulsatile swelling and bruit | Extracranial ICA pseudoaneurysm with ICA-internal jugular vein AVF | |||||||

| de Borst et al. 2006 | 1 | 13ys | 1 F | Bicycle-motor vehicle accident | Hemiplegia with unilateral facial palsy, ipsilateral hemianopia | < some hours and few days after | Brain CT, brain MRI, and MRA | Bilateral ICAD | Unilateral ACA infarct |

| Chokyu et al. 2006 | 1 | 61ys | 1 F | Accidental strangulation | Hemiparesis, unilateral facial palsy | 1 day (soon after the trauma she also had tetraparesis due to spinal cord injury) | Brain CT, cervical MRI, MRA | Bilateral CCAD | Unilateral cerebral infarct |

| Yang et al. 2006 | 3 | 22ys | 3 M | Fall (1) | Altered consciousness, hemiparesis | 2 days | Brain CT, neck CTA, DUS | ICA thrombus and caliber narrowing | Neck abrasion and bruit |

| 47ys | MVA (2) | Altered consciousness | < some hours | Brain CT, cervical X ray, angiography | ICAD | Frontal scalp laceration, some cranial and C2 fractures, pneumocranium, subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||

| 48ys | Altered consciousness, visual acuity reduction, extraocular movements alteration, hemiparesis | 7 days | Brain and facial CT, angiography | Multiple craniofacial fractures, haemorragic ACA and MCA infarct | |||||

| Jariwala et al. 2006 | 1 | 17ys | F | Car accident | Progressive consciousness alteration, hemiparesis and sensation loss | < some hours | Brain and neck spine CT | ICAD | MCA and partially PCA infarct |

| Brain CT, MRI, MRA | |||||||||

| Pierrot et al. 2006 | 2 | 4,5ys | 2 F | Soft palate injury (with oral bleeding) | Altered consciousness, hemiplegia, central facial palsy, aphasia | 24 hours | Brain CT and MRI | ICAD with parietal thrombus | Insular cortex infarct |

| 3,5ys | - | < some hours | - | ||||||

| Lin et al. 2007 | 1 | 7ys | 1 M | Playing at a water park | Head and neck pain, vomiting, hemiparesis, Babinski’s sign, hemifacial palsy with slurred speech and uvula deviation | < some hours | Brain CT, MRI, MRA, angiography | ICAD | Acute cerebral infarct |

| Lo et al. 2007 | 10 | 29.7ys (range 16-57) | 7 M, 3 F | MVA (2), unspecified (8) | Altered consciousness (2), unspecified (8) | - | Brain CT, CTA, | ICA pseudoaneurysm | Craniofacial fractures |

| Zhou et al. 2007 | 1 | 28ys | 1 M | Bungee jumping (no fall) | Right arm paraesthesia | < some hours | Neck US, brain MRI, MRA | ICAD with intramural haematoma | - |

| Schulte et al. 2008 | 2 | 27 and 39ys | 1 M, 1 F | Blunt neck trauma |

TIA, headache, vertigo | - | DUS, CTA | CAD | - |

| Fuse et al. 2008 | 1 | 42ys | M | Neck injury dropping a heavy load | - | - | Head and neck MRI, angiography, single photon emission CT | ICAD | Tracheal fracture, recurrent transient bilateral nerve paralysis; cerebral infarct, |

| Flaherty and Flynn 2008 | 1 | 34ys | F | Hand assault (hit on the face) | Horner’s syndrome | 4 days | Brain CT, neck CTA | ICAD | - |

| Vadikolias et al. 2008 | 1 | 48ys | M | Intense jackhammer use | Hemiparesis | < some hours | Brain CT, DUS, TCD | ICAD | MCA infarct with haemorrage |

| Moriarty et al. 2009 | 1 | 10mo | F | Soft palate injury | Altered consciousness and progressive hemiplegia (no oral bleeding) | 1 day | Brain CT, brain and neck MRI, neck and intracranial MRA | ICAD with thrombus | MCA infarct with haemorrhage, MCA thrombus |

| Molacek et al. 2012 | 1 | 49ys | F | Strangulation attempt | Altered consciousness | - | Brain and neck CTA | Bilateral ICAD | Neck strangulation groove |

| Keilani et al. 2010 | 1 | 52ys | F | Horse riding fall and multiple injuries | Altered consciousness | 1 day (at admission, she had several other lesions which required surgery) | Brain MRI, angiography | ICAD with pseudoaneurysm | Multiple cerebral infarcts |

| Stager et al. 2011 | 1 | 55ys | F | MVA | - | - | CTA, angiography with IVUS | ICAD | Several other lesions, no brain injury |

| Herrera et al. 2011 | 14 | - | - | Gunshot and stab injuries | Bleeding, pulsatile mass, neck bruit, hematoma, stroke, dementia syndrome | - | - | Pseudoaneurysm, AVF, dissection, active bleeding | - |

| Fridley et al. 2011 | 1 | 40ys | M | Wakeboarding | Headache, hemiplegia | 1 day | Head CT, MRI, MRA, angiography | ICAD | Unilateral basal ganglia and internal capsule infarct |

| Taşcılar et al. 2011 | 1 | 31ys | M | Football (neck struck by the ball) | Altered consciousness, hemifacial paresis, hemiplegia, aphasia, positive Babinski’s sign | < 6 hours | CT, DUS, MRA | ICAD | MCA infarct |

| van Wessem et al. 2011 | 5 | 20ys | 2 F | Car accident | Altered consciousness | < some hours | Head and cervical CT, DUS, CTA | ICAD | C0 condyle fracture, MCA infarct |

| 49ys | Altered consciousness, legs paralysis and sensory loss | Brain CT, CTA and angiography | Multiple spine fractures, right temporal lobe hematoma |

||||||

| 19ys | 1 M | Altered consciousness | Brain and cervical CT and CTA | Multiple facial, C0 condyle, skull base fractures, MCA infarct | |||||

| 53ys | M | Truck accident | Sudden decrease of consciousness, hemiparesis, unilateral Babinski’s sign | < some hours | Brain and neck CT | Bilateral C0 fracture, MCA infarct | |||

| 19ys | M | Motorbike accident | Altered consciousness, different blood pressure between the arms | < some hours | Aortic CTA | - | Multiple cranial and skull base fractures, multiple intracerebral hematomas, ACA and MCA infarct |

||

| Still altered consciousness, spontaneous bilateral stretching of both arms and hemiparesis | 7 and 8 days | Brain CT and CTA | |||||||

| Cohen et al. 2012 | 23 | 44ys (range 17-66) | 19 M, 4 F | Multiple trauma (11), penetrating neck injury (2), minor cervico-cranial trauma (10) | Ischaemic stroke symptoms (14), TIA (3), Horner’s syndrome (1), carotidynia (1) | 2 hours up to 21 days | Head and neck CT, CTA (all) | ICAD | - |

| Makhlouf et al. 2013 | 1 | 60ys | 1 F | Hand assault (hit on the head) | Headache | < some hours | Cervical X-rays | ICAD with pseudoaneurysm | Unilateral corona radiata infarct |

| Unilateral facial palsy and Horner’s syndrome | 3 months | Brain MRI and MRA | |||||||

| Prasad et al. 2013 | 1 | 22ys | F | MVA | Altered consciousness | < some hours | Head CT, angiography | ICAD with AVF | Multiple facial fractures, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral oedema |

| Seth et al. 2013 | 47 | 34ys (range 17-71) | 32 M, 15 F | Blunt (47) and penetrating (6) injuries | - | - | CT or conventional angiography | Unilateral (41) and bilateral (6) ICAD with or without pseudoaneurysm | - |

| Hostettler et al. 2013 | 1 | 47ys | 1 M | Softball blunt injury | Neck and head pain, amaurosis fugax, Horner’s syndrome | 1 week | Brain CT, DUS, MRA | ICAD with mural thrombus | - |

| Orman et al. 2013 | 5 | 3.6ys | F | Fall | Hemiplegia, aphasia | - | CT, MRI and/or CTA/MRA | ICAD | Cerebral infarct (3) |

| 7.6ys | M | Head trauma | - | ||||||

| 3.1ys | M | MVA | Focal seizure | ||||||

| 1.9ys | F | Head trauma | Altered mental state | ||||||

| 1ys | M | Fall | Unilateral hypoesthesia | ||||||

| Kalantzis et al. 2014 | 1 | 39ys | 1 M | Snowboarding fall | Horner’s syndrome, periocular and neck pain | 2 days | Head and neck CT, MRI, MRA | ICAD | - |

| Correa and Martinez 2014 | 1 | 41ys | 1 M | Blunt head and neck trauma | Transient loss of consciousness | < some hours | - | ICAD with stenosis | Neck abrasion, carotid bruit; acute cerebral infarct |

| Headache, unilateral visual loss, hemiparesis, unilateral hyperreflexia and Babinski’s sign | 48 hours | Brain CT, MRI, angiography | |||||||

| Crönlein et al. 2015 | 1 | 28ys | 1 F | Car accident | Altered consciousness, head pain, anisocoria | < some hours | Total body CT | Bilateral ICAD | Unilateral central region cerebral infarct |

| CTA, US | |||||||||

| Uhrenholt et al. 2015 | 1 | 42ys | 1 M | Sudden braking | Neck pain, headache, cramps, gradually altered consciousness | < some hours | Brain CT, (PMCT) | ICAD with pseudoaneurysm and mural thrombus | Subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| Morton et al. 2016 | 39 | 41ys | 22 M, 17 F | - | - | - | Head and neck CTA | ICA pseudoaneurysm (bilateral in 4 cases) | Cerebral infarct (7) |

| Griessenauer et al. 2016 | 2 | 21ys | 1 M, 1 F | MVA | Altered consciousness | < some hours | Head CT, CTA | ICA aneurysm | Cranial and facial fractures, intracranial haemorrhage |

| Taoussi et al. 2017 | 1 | 29ys | F | Car accident | Dysphasia, upper limb hemiparesis, | < 12 hours | MRI | Bilateral ICAD | Multiple cerebral infarct |

| Cebeci et al. 2018 | 1 | 10ys | 1 M | Trivial shoulder trauma | Headache, speech impairment, vomiting, and facial paralysis | 6 hours | Head MRI and MRA | ICAD | . |

| Ariyada et al. 2019 | 1 | 23ys | 1 M | Pedestrian run over | Altered consciousness (recovered in some hours) | < some hours | Whole body CT | - | Thin subdural hematoma, odontoid process, pelvis, and limbs’ fracture |

| Bleariness | 1 month | CT angiography, MRA, DSA | Bilateral ICAD | VAD with thrombus | |||||

| Gabriel et al. 2019 | 1 | 37ys | 1 F | CrossFit training | Headache, dizziness, neck pain, unilateral amaurosis fugax | 1 hour | Cervical and chest X-ray, DUS, brain CT, MRI, angiography | Bilateral ICAD | Unilateral corona radiata infarct |

| Hemiplegia, dyslalia, aphasia, dysphagia, unilateral facial droop | 48 hours | ||||||||

| Petetta et al. 2019 | 1 | 44ys | M | Motorcycle accident | Altered consciousness, traumatic shock | < some hours | Whole body CT | - | Several other lesions, no brain injury |

| Altered consciousness | 5 days | Brain CT, MRI, CTA | Bilateral ICAD with intraluminal thrombus | Multiple cerebral infarct | |||||

| Wang et al. 2020 | 6 | 52.67 ys (range 43-62) | 5 M, 1 F | Car accident (2), motorcycle accident (2), fall from height (1), blunt head injury (1) | Paralysis (2), altered consciousness (2), headache (1), neck pain (1) | 4-45 hours | CT, CTA, DUS, DSA, MRI, TCD in various combinations | ICAD | Cerebral infarct (6) |

| Total articles 77 | Total subjects 334 | Mean age 18.9ys | 200 M 113 F | Total articles 77 | - | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: ACA indicates anterior cerebral artery; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; CA, cerebral artery; CAD, carotid artery dissection; CCAD, common carotid artery dissection; CT, computer tomography; CTA, computer tomography angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; DUS, duplex ultrasonography; ECAD, external carotid artery dissection; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; ICA, internal carotid artery; ICAD, internal carotid artery dissection; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MCA, middle cerebral artery; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MVA, motor vehicle accident; PMCT, post-mortem computer tomography; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; TCD, transcranial doppler sonography; VAD, vertebral artery dissection.

As shown in Table 2, the trauma mechanisms causing TICAD were gathered from the published reports, when possible, and categorised in five classes (“Type of trauma”). The classes were also divided into 28 subclasses (“subtype of trauma”) to provide a more detailed analysis. Table 2 shows the results of this re-analysis; the proportion of each class and subclass of the total reported cases is also shown.

Table 2.

Traumatic events causing internal carotid artery dissection in the literature. Only cases in which the traumatic event was reported are included. MVA indicates a motor vehicle accident.

| Type of Trauma | Subtype of Trauma | Number of Cases | Tot. | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic accidents | Generic MVA | 36 | 94 | [7, 8, 20, 23, 26, 30, 45, 46, 48, 49, 51-53, 56, 70, 83, 92] |

| Car accidents | 39 | [20, 22, 25, 28, 29, 31- 38, 40, 43, 47, 54, 55, 61, 63, 112] | ||

| Truck accident | 1 | [38] | ||

| Motorcycle and moped accidents | 13 | [7, 22, 25, 38, 39, 42, 44, 50, 55, 61, 70] | ||

| Bicycle accidents | 3 | [7, 57, 58] | ||

| Pedestrian accidents | 2 | [41, 46] | ||

| Head or neck blunt injuries | Not specified/indirect | 48 | 76 | [19, 24, 25, 55, 69, 71, 86, 92, 98, 99, 101, 103] |

| Fistfight/ assault with or without blunt weapon | 7 | [6, 12, 22, 25, 46, 68] | ||

| Hanging or strangulation | 8 | [17, 48, 63-67] | ||

| Soft palate/pharynx injury | 5 | [93-96] | ||

| Trivial or minor traumas | 8 | [80-84, 89-91] | ||

| Penetrating injuries | Not specified | 22 | 27 | [88, 99, 100, 103] |

| Gunshot | 3 | [68, 86, 87] | ||

| Stab wound | 2 | [86, 101] | ||

| Sport (with or without specific blunt trauma) | Horse-riding fall | 3 | 19 | [46, 59, 60] |

| Football | 4 | [24, 25, 76] | ||

| Snowboarding | 1 | [75] | ||

| Water-skiing/ wakeboarding | 2 | [25, 77] | ||

| Skydiving | 1 | [25] | ||

| Basketball | 1 | [7] | ||

| Softball | 3 | [73, 74] | ||

| Taekwondo | 1 | [79] | ||

| CrossFit | 1 | [72] | ||

| Bungee jumping | 1 | [78] | ||

| Wrestling | 1 | [62] | ||

| Falls | Not specific height | 6 | 11 | [8, 24, 55, 61, 62] |

| < 3 meters | 4 | [22, 92] | ||

| > 3 meters | 1 | [20] | ||

| Total | 227 | |||

3.1. Brief Description of the Studies Published Before 1990

The very first report of TICAD dates back to 1872 when Verneuil autopsied a person who died of head trauma [15, 16]. He found an intimal tear of the ICA and a thrombus in its lumen that extended to the middle cerebral artery. Subsequently, in 1944, Northcroft and Morgan described dissection of the left ICA that occurred by accidental hanging [17]. In 1967, Yamada et al. investigated 51 cases of carotid artery occlusion due to blunt injury [18]. Then, a report of ICAD following a blunt head injury was published by Sullivan et al. [19]. In 1980, Stringer and Kelly reported six cases of traumatic extracranial ICAD [20]. They suggested that the intimal injuries were produced by hyperextension and lateral flexion of the neck, which caused the artery wall to be stretched. An additional two cases were described by Krajewski and Hertzer, while another series of six cases were reported by Zelenock et al. [21, 22]. In their work, they reported the causes to be motor vehicle accidents in three cases, falls from less than three metres in two cases, and direct neck blunt trauma (fistfight) in the last case. Six cases were described by Pozzati et al. in two different papers [7, 23]. Peculiarly, five patients had neurological manifestations at least two weeks after the traumatic event (range two weeks – six months). In 1987, Morgan et al. described five other cases of post-traumatic ICA injury, two involving children [24]. Mokri et al. reported 18 cases of extracranial ICAD as a consequence of blunt head or neck trauma [25]. Again, motor vehicle accidents were the major cause. Watridge et al. described 24 cases of patients admitted to their medical centre after trauma [26]. The presenting symptoms varied (hemiparesis, aphasia, etc.) No patients presented with external signs of a direct neck injury, while two patients had cervical and thoracic spinal fractures. Prompt head CT scans were performed in all cases, but 17 of the 24 patients did not show any cerebral alterations within the first four hours, while 12 of those 17 later developed areas of cerebral infarction. Cerebral arteriography was then performed, revealing 18 monolateral CADs and six bilateral CADs. In 1990, Mokri reported a series of patients suffering from ICAD, 21 of which were traumatic [27]. At follow-up, traumatic dissections appeared to be more likely to cause permanent neurological deficits than spontaneous dissections.

3.2. Brief Description of the Studies Published from 1990 to the Present

From 1990 to the present, several articles concerning TICAD and traumatic internal carotid artery injuries have been published. Regarding the type of trauma causing the injury, traffic accidents are the most common (94/227 cases, Table 2). For example, Reddy et al. reported the autopsy of a woman who developed ICAD as a consequence of a car accident [28]. The authors suggested that arterial injury was caused by seatbelt trauma. In another article, the case of a woman who developed tongue deviation four months after a car accident was described [29]. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed ICAD plus intramural haematoma. In addition, angiography also showed tortuosity of the artery, which in the authors’ opinion could predispose patients to dissection in case of a traumatic event. A series of six cases concerning ICADs from motor vehicle accidents highlighted the importance of initial patient evaluations and timely angiography examinations [30]. In fact, in four of those cases, the diagnosis of ICAD was made within 6 hours of hospital admission, while in the remaining cases, the patients were diagnosed within at least the third day of hospitalization. All patients showed normal ICA contours at the last follow-up angiography, even though three of them still had neurological deficits. Another case of ICAD subsequent to a motor vehicle accident was described by Matsuura et al. [31]. In this case, a woman was driving without a fastened seat belt. She developed neurological symptoms after three days of hospitalization, and angiography was performed, revealing a right ICAD with a pseudoaneurysm. Conversely, Babovic et al. reported the case of a woman who was driving her car with a fastened seat belt when she was involved in a high-speed collision [32]. The airbag deployed. She had several lesions, including facial bone fractures requiring surgical fixation. Some days after the surgery, on the tenth day after admission, she complained of unilateral progressive visual loss. Through imaging, they found that the woman had bilateral ICADs with bilateral thrombus formation, causing embolization and cerebral infarction. A similar case was also presented by Jariwala et al. [33]. Duncan et al. described the analogous case of a man who had a frontal collision with the seat belt fastened and airbag deployment [34]. A brain CT scan and angiography diagnosed bilateral ICADs with a thrombus in the right ICA. The authors suggested the aetiological role of airbag deployment. In addition, this case is peculiar because there was evidence of ICA fibromuscular dysplasia, which could be a predisposing pre-existing risk factor for traumatic dissection. Another particular case of ICAD associated with a car accident was presented by Uhrenholt et al. [35]. A man was diagnosed with unilateral ICAD as a consequence of a whiplash injury due to sudden braking while driving a car. ICAD was directly traced back to whiplash trauma since the man did not experience any other injury. Another interesting case was published by Fusonie et al. [36]. A young man experienced three episodes of transient unilateral upper limb weakness over a period of four months. He said he was involved in a car accident several years before. He was diagnosed with a right ICA pseudoaneurysm and underwent covered stent exclusion; afterward, he did not experience any other episodes. In many other works, motor vehicle accidents, with or without direct head/neck trauma, were the cause of ICAD [8, 37-56]. In contrast, only three cases of post-traumatic internal carotid artery lesions related to bicycle accidents have been reported [7, 57, 58].

Some cases described horse riding accidents [46, 59, 60]. A fall from height was the cause of ICAD in 11/227 cases [8, 22, 24, 55, 61, 62].

Direct, blunt trauma to the neck is another possible mechanism of ICA lesions. For example, eight cases of ICAD as a consequence of hanging and/or strangling have been described [48, 63-67]. There are cases of ICAD following assault, with or without some kind of unsharpened weapon, in which a blunt head or neck injury was probably the cause of the arterial lesion [6, 12, 22, 25, 46, 68]. Hughes et al. collected seven cases of ICAD after blunt head trauma [69]. Peculiarly, in all seven cases, ICAD was an incidental finding during cervical spine and/or brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or angiography performed for other reasons. No evidence of cerebral infarct was seen on brain CT, and the patients did not present any neurological symptoms correlated to ICAD. Lo et al. collected 18 cases of post-traumatic ICA lesions (10 pseudoaneurysms) and suggested a correlation with craniofacial fractures [70]. Unfortunately, the authors did not specify the traumatic causes of all the cases. Other papers concerning blunt head and/or neck trauma are described in Table 1 [71]. Some authors described cases of TICAD related to athletics, both in cases with and without some kind of trauma [25, 62, 72-79]. For instance, in Mokri et al.’s work, there are cases correlated to football, water skiing, and skydiving [25]. Fridley et al. described a case of TICAD following wakeboarding [77]. Zhou et al. published the case of a young man who went bungee jumping and experienced neck pain after ten minutes [78]. Some hours later, he also experienced paraesthesia in one arm. A carotid artery ultrasound and then brain MRA revealed left CCA and ICA dissection with intramural haematoma. In another case, a man developed a headache during taekwondo training [79]. Days later, he developed progressive neurologic deficits, such as aphasia, visual disturbances, hemiparesis, and sensory loss. A brain CT scan followed by MRI and MR angiography revealed unilateral ICAD with middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction.

Alimi et al. focused on bilateral TICAD, collecting a series of eight cases [61]. Most of them occurred after car accidents, both with or without the seat belt fastened, while in two cases, the TICADs occurred after a moped accident and after a stairway fall. Another case of bilateral ICAD was described by Kumar et al. [80]. The authors correlated the dissection to a minor trauma that occurred while the patient was vomiting. Some hours later, he developed hemiplegia, loss of vision in one eye, slurred speech, and a decrease in consciousness. An MRI showed an infarct in the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and MCA territory, a left ICAD with occlusion, and a right ICA intimal flap with normal blood flow. Lee and Jensen also described a case of bilateral ICAD following minor trauma [81]. Their patient developed headache and visual disturbances days after riding a mountain bicycle despite not having any accidents or falling off the bike. Vadikolias et al. presented the case of a man who developed ICAD after intense jackhammer use (several hours) in a horizontal position [82].

Dissections from trivial injury were also reported by Alimi et al. [83]. The authors described a case of ICA stenosis after cervical manipulation and identified neck hyperextension as the cause of the arterial lesion. In the study by Fuse et al., an indirect neck injury consequent to dropping a heavy load was the cause of ICAD, which was diagnosed three months after the trauma by a screening MRI [84]. Pezzini et al. reported a case of ICAD after playing the French horn. The patient also had two risk factors for spontaneous dissection (hyperhomocysteinemia and aberrant connective tissue morphology), so the authors considered the case as SICAD. They also questioned the real correlation between trivial traumas and TICAD [85].

TICAD has also been described in correlation with penetrating neck injuries, such as gunshots and stab wounds [66, 86-88]. In particular, Herrera et al. collected 14 cases of ICA injuries due to gunshot or stab injuries [88].

With regard to the paediatric population, aside from the previously mentioned work by Morgan et al. [24], in the literature, there are at least 14 cases of children (< 16 years old) who developed TICAD, often in relation to minor trauma [58, 89-96]. In particular, the causative event was trauma to the soft palate/pharynx (fall while holding something in the mouth or falling with the mouth open against a hard object) in 5/227 cases [93-96].

In some studies, the authors did not focus on or specifically report the traumatic causes of ICAD [86, 88, 97-103]. For example, Vishteh et al., Herrera et al., and Cohen et al. published retrospective studies evaluating only patients who underwent revascularization procedures [86, 88, 103].

3.3. Case Report

A 54-year-old man with no medical history was involved in a high-speed head-on collision against a lamppost while driving a truck. The truck’s frame was highly damaged during the impact. The man experienced a sudden transient loss of consciousness soon after the accident. He was immediately transferred to the local emergency department, and the first evaluation revealed a blood pressure of 130/85 mmHg, heart rate of 85 bpm, oxygen saturation of 96%, right frontal skin abrasion, crush injuries of the right food with an exposed fracture, and normal neurological, thoracic, and abdominal examination results. The patient was agitated, and therefore 20 mg of midazolam was administered. An X-ray examination of the right foot confirmed displaced fractures in the tibia and fibula. A whole-body CT scan without contrast was also performed, showing a displaced fracture of the right arc of the C1 vertebra with atlanto-occipital disarticulation; multiple left pulmonary contusions associated with pneumatocele; and a fracture in the D10 vertebral body. No ischaemic or haemorrhagic brain injuries were present. A cervical collar was prescribed, and the patient was admitted to the Orthopaedic Department of the same hospital to undergo surgery for the foot fracture. Two days after admission, he complained that he could not move his left upper limb, and paralysis was confirmed during the physical examination. Therefore, brain CT plus CT angiography was performed, revealing a right posterior cortico-subcortical temporoparietal insular ischaemic lesion with a median shift and a right ICAD with almost complete lumen obstruction and consequent decrease in the right middle cerebral artery blood flow (Figs. 2 and 3).

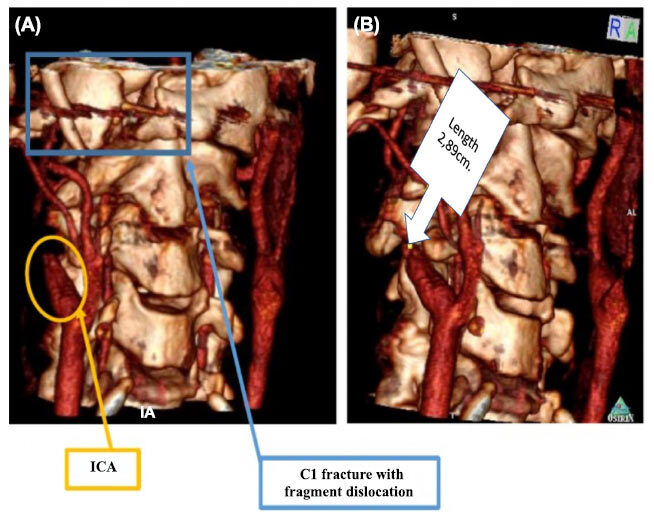

Fig. (2).

TC angiography performed soon after neurologic manifestation showed a right ICAD with almost completed lumen obstruction and consequent right middle cerebral artery blood flow decrease.

Fig. (3).

CT 3D reconstruction details showing C1 dislocated fragment could not be the cause of the TICAD.

A revascularization procedure was not indicated. The patient received 18% mannitol and was transferred to the stroke unit. Here, the physical examination showed drowsiness, left hemiplegia, right-sided head deviation, divergent strabismus of the right eye, bilateral miosis reactive to light stimuli, and Cheyne-Stokes respiration, while the vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 130/70 mmHg, heart rate 70 bpm, oxygen saturation 97% (85% in apnoea phases), and body temperature 36,6°C. The patient received oxygen therapy; the vital signs were constantly monitored. During the following hours, he experienced two episodes of left hemibody fasciculations and breathing alterations and was treated with lorazepam. A day later, he was comatose, with bilateral mydriasis and stertorous breathing. A brain CT scan showed progression of the ischaemic lesion with a mass effect, left median shift, and left uncal herniation. He underwent a decompressive hemicraniectomy. During the surgery, a partial temporal lobectomy was also performed since the cerebral parenchyma was not irrorated. Nevertheless, his neurological status deteriorated further until he was declared brain-dead.

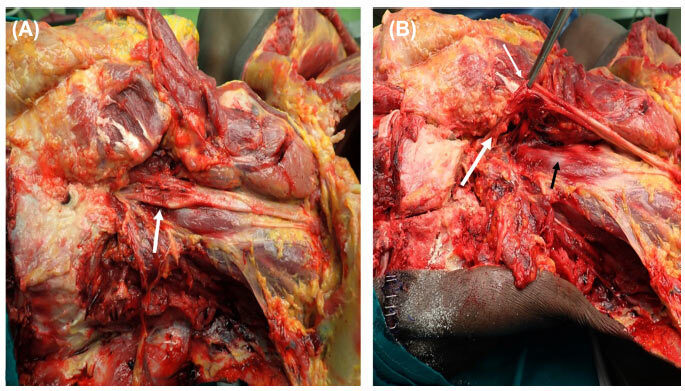

A forensic autopsy was then performed and revealed, aside from cranial surgery sequelae and obvious brain damage, modest adventitial haemorrhagic infiltration of the right ICA a few centimetres distal to the right carotid bifurcation (Fig. 4).

Fig. (4).

Right common, internal, and external carotid arteries dissection. Right ICA showed a modest adventitial haemorrhagic infiltration a few centimetres upper than the carotid bifurcation.

The right common, internal, and external carotid arteries were sampled and then studied after formaldehyde fixation (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. (5).

Right common, internal, and external carotid arteries dissection and collection. ICA was sectioned at its petrous level.

Fig. (6).

Right common, internal, and external carotid arteries sample section and macroscopic.

Histological examination was performed, confirming the presence of cerebral oedema and right ICAD. Specifically, the ICA presented an intramural haematoma with intimal and media laceration, and a thrombus was confirmed to be in the lumen (Fig. 7).

Fig. (7).

Right ICAD histological examination revealed an intramural hematoma with intimal and media laceration and a thrombus into the lumen.

4. DISCUSSION

We presented the case of a middle-aged man who was involved in a road traffic accident. He was transferred to the emergency department after a sudden transient loss of consciousness. No brain injuries were identified on the CT scan. Two days after hospitalization, while he was waiting for surgical treatment for a foot fracture, he developed left upper limb paralysis. Brain CT and CT angiography showed a large ischaemic lesion and right ICAD. Even though a decompressive hemicraniectomy was performed, he died after a few days. A forensic autopsy was required. This confirmed that right ICAD was the cause of brain injury.

ICAD represents the cause of ictus cerebri in 2% of cases, but it explains approximately 20% of all cases of cerebral infarction among the young adult population [1, 2]. It has been estimated that carotid injuries could complicate 0,32% of cases of general blunt trauma, and the percentage seems to be higher in cases of multiple severe traumas [104, 105]. Specifically, TICAD seems to complicate approximately 0,21% of all traumas [69]. TICAD can have devastating consequences, from permanent neurological impairment to death [106]. In addition, follow-up studies have demonstrated that dissections do not always heal spontaneously, so the risk of complications could persist [14, 107]. Thus, even if TICAD is a rare condition, a prompt diagnosis is essential.

Usually, TICAD is diagnosed when neurological symptoms have already occurred [9]. The clinical presentation varies, but the condition is mostly represented by headache, altered consciousness, Horner’s syndrome, and focal neurological symptoms such as hemiparesis/hemiparalysis. Concerning the timing of clinical presentation, the trauma-to-symptom interval varies from a few minutes up to months. In a peculiar case, the clinical manifestations occurred several years after the traumatic event [36]. Nevertheless, in most cases, the trauma-to-symptom interval does not exceed a week.

In such traumatic cases, there are often concomitant injuries, which can hide or mitigate the neurological manifestations of TICAD. In addition, other life-threatening injuries could require immediate treatment and/or surgery (i.e., abdominal organ laceration), delaying a proper neurological examination.

Given the above, TICAD should be taken into consideration when a young adult or middle-aged patient presents with severe blunt trauma, although there are no specific guidelines regarding TICAD screening [9]. The risk factors for a blunt carotid injury that indicate examinations to exclude TICAD are cervical hyperextension or hyperflexion, a direct head/neck blunt injury, seat-belt sign, a GCS score </= 6, diffuse axonal brain injury, any kind of cervical spine or craniofacial fracture [14].

In addition, understanding which kind of traumatic event is most associated with TICAD could help clinicians optimize their diagnostic process. In the literature, TICAD is mostly correlated with traffic accidents (41,4%), specifically to car accidents (at least 17,2%), and to direct or indirect head and cervical trauma (33,5%). Usually, TICAD is a consequence of a high-energy collision/blunt trauma, but in a few cases, TICADs due to trivial traumas have also been reported.

The mechanism of TICAD development has been mostly referred to as vigorous extension and flexion of the cervical spine and rotation of the skull. During such movements, the ICA is stretched, and the arterial wall may be damaged. Shear forces seem to be more intense where the ICA movement is averted by the surrounding anatomical structure, such as the skull base [57]. Nevertheless, TICAD could be found in both the extracranial and intracranial ICAs. When TICAD is extracranially located, neck duplex ultrasonography (DUS) could help to identify arterial wall injury. Therefore, DUS could be suggested as a non-invasive screening tool, but it has low sensitivity, and its use is limited to extracranial arteries [50]. Gouny et al. emphasized the importance of MRI, which can precisely visualise the dissection [44]. An aggressive angiographic evaluation has also been proposed [108]. Brommeland et al. recommend applying the Denver screening criteria and then performing computed tomography angiography (CTA) in cases of blunt trauma [109]. Nevertheless, those indications have not yet been completely accepted by the scientific community, and there is no uniform screening strategy among physicians.

Regarding ICAD treatment, both medical and surgical management have been described. Endovascular and surgical approaches, while effective, pose a greater risk for severe complications than medical management. However, antithrombotic treatment has been shown to be especially effective in the management of carotid dissection during endovascular procedures. Indeed, a better outcome may be expected with the combination of intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular methods (stenting and thromboaspiration), as recent reports have suggested a better outcome after r-TPA treatment using stent-assisted intra-arterial thrombolysis [110]. While antithrombotic treatment has been shown to be effective in the management of carotid dissection, no treatment guidelines have favoured anticoagulation over antiplatelet agents. The majority of cerebrovascular dissections heal by themselves, and the risk of developing new ischaemic complications has been reported to be low; however, in the case of recurrent ischaemic symptoms, the outcomes can be devastating. This potential severity deems treatment necessary to prevent the development of permanent neurological deficits. Antithrombotic therapy with either antiplatelets or anticoagulants is the mainstay of treatment to prevent thromboembolic complications. Nevertheless, both antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents can be used in the management of intracranial carotid dissection with similar rates of new or recurrent ischaemic stroke, TIA, and hemorrhage [111].

With regard to the case presented in this paper, ICAD can be considered a consequence of motor vehicle accidents despite the absence of any signs suggesting a direct neck or head injury. In addition, from the neck CT images obtained during hospitalization and the autopsy findings, it was possible to exclude that the C1 fracture fragments were involved in ICAD development (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the dissection was probably due to stretching or compression of the ICA as a consequence of sudden deceleration. As already said, many authors suggest that hyperextension and rotation or direct compression may be the cause of TICAD [12, 22, 57, 90].

From a medico-legal point of view, another issue is the possibility of a medical liability claim. The absence of specific and internationally accepted guidelines leaves physicians alone when facing the matter of TICAD screening/diagnostic protocols. In our case, the reasons behind the diagnostic delay, other than the absence of specific guidelines, were the trauma-to-symptom interval (two days) and the presence of other injuries requiring timely surgery. Then, when the ICAD diagnosis was made, the brain was already gravely injured, so vascular repair surgery was not possible [112]. This case highlights the importance of screening guidelines to help physicians anticipate a TICAD diagnosis before symptoms develop and prevent permanent neurological impairment or attenuate poor prognoses.

CONCLUSION

TICAD is a rare condition largely described in correlation with traffic accidents. It mainly affects the young adult population, and it can cause permanent neurological defects or even death. TICAD is usually diagnosed when neurological symptoms and cerebral damage have already occurred. The need for screening in cases of head/neck injury is debated, and even if some authors have suggested diagnostic criteria, there is no consensus among physicians. Therefore, medical liability claims correlated to TICAD are possible. The case reported in this paper is an emblematic example of a delayed TICAD diagnosis that resulted in patient death. This case highlights the need for screening guidelines to attenuate not only poor prognoses but also avoid medico-legal claims. Identifying which type of trauma is more likely to cause ICAD could be a good way to help increase suspicion for this infrequent condition, despite the absence of specific and internationally accepted guidelines. Through a literature review, we have confirmed that TICAD is mainly described as a consequence of traffic accidents. In such cases and, in general, when a direct or indirect neck injury is described, ICA stretching or compression needs to be suspected. Despite the absence of internationally accepted guidelines, a thorough and detailed trauma mechanism anamnesis is necessary to identify the cases in which MRI or angiography are indicated for early diagnosis of TICAD and to prevent devastating neurological outcomes.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

A.F. analysed and interpreted the patient data; A.M., performed the histological examination; E.T., V.F. were involved in writing—review, editing, and supervision; M.D.P. and R.L.R. contributed in writing the manuscript; A.C.M. and A.D.M. performed the literature search. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ACA

Anterior cerebral artery

- CT

Computer tomography

- CTA

Computer tomography angiography

- DUS

Duplex ultrasonography

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- ICA

Internal carotid artery

- ICAD

Internal carotid artery dissection

- MCA

Middle cerebral artery

- MRA

Magnetic resonance angiography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was granted by the Judicial Authority governing specific information included herein.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed for the study.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zetterling M., Carlström C., Konrad P. Internal carotid artery dissection. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2000;101(1):1–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kray J.E., Dombrovskiy V.Y., Vogel T.R. Carotid artery dissection and motor vehicle trauma: patient demographics, associated injuries and impact of treatment on cost and length of stay. BMC Emerg. Med. 2016;16(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s12873-016-0088-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzales-Portillo F., Bruno A., Biller J. Outcome of extracranial cervicocephalic arterial dissections: a follow-up study. Neurol. Res. 2002;24(4):395–398. doi: 10.1179/016164102101200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas L.C., Rivett D.A., Attia J.R., Levi C.R. Risk factors and clinical presentation of craniocervical arterial dissection: a prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2012;13:164. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergquist B.J., Boone S.C., Whaley R.A. Traumatic dissection of the internal carotid artery treated by ECIC anastomosis. Stroke. 1981;12(1):73–76. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.12.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makhlouf F., Scolan V., Detante O., Barret L., Paysant F. Post-traumatic dissection of the internal carotid artery associated with ipsilateral facial nerve paralysis: diagnostic and forensic issues. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2013;20(7):867–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pozzati E., Giuliani G., Poppi M., Faenza A. Blunt traumatic carotid dissection with delayed symptoms. Stroke. 1989;20(3):412–416. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.20.3.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang S.T., Huang Y.C., Chuang C.C., Hsu P.W. Traumatic internal carotid artery dissection. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2006;13(1):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galyfos G., Filis K., Sigala F., Sianou A. Traumatic carotid artery dissection: A different entity without specific guidelines. Vasc. Spec. Int. 2016;32(1):1–5. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2016.32.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabian T.C., Patton J.H., Jr, Croce M.A., Minard G., Kudsk K.A., Pritchard F.E. Blunt carotid injury. Importance of early diagnosis and anticoagulant therapy. Ann. Surg. 1996;223(5):513–522. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199605000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulloy J.P., Flick P.A., Gold R.E. Blunt carotid injury: a review. Radiology. 1998;207(3):571–585. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.3.9609876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanzone A.G., Torres H., Doundoulakis S.H. Blunt trauma to the carotid arteries. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1995;13(3):327–330. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biffl W.L., Moore E.E., Offner P.J., Brega K.E., Franciose R.J., Burch J.M. Blunt carotid arterial injuries: implications of a new grading scale. J. Trauma. 1999;47(5):845–853. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199911000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verneuil M. Contusions multiples, délire violent, hémiplégia à droite, signes de compression cerébrale. Bull. Acad. Med. 1872;1:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grond-Ginsbach C., Meisenbacher K., Böckler D., Leys D. The first case of traumatic internal carotid arterial dissection? Verneuil’s case report from 1872. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 2021;177(3):162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nothcroft G.B., Morgan A.D. A fatal case of traumatic thrombosis of the internal carotid artery. Br. J. Surg. 1944;32:105–107. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18003212518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada S., Kindt G.W., Youmans J.R. Carotid artery occlusion due to nonpenetrating injury. J. Trauma. 1967;7(3):333–342. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan H.G., Vines F.S., Becker D.P. Sequelae of indirect internal carotid injury. Radiology. 1973;109(1):91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stringer W.L., Kelly D.L., Jr Traumatic dissection of the extracranial internal carotid artery. Neurosurgery. 1980;6(2):123–130. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krajewski L.P., Hertzer N.R. Blunt carotid artery trauma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ann. Surg. 1980;191(3):341–346. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198003000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zelenock G.B., Kazmers A., Whitehouse W.M., Jr, Graham L.M., Erlandson E.E., Cronenwett J.L., Lindenauer S.M., Stanley J.C. Extracranial internal carotid artery dissections: noniatrogenic traumatic lesions. Arch. Surg. 1982;117(4):425–432. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380280023006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pozzati E., Gaist G., Servadei F. Traumatic aneurysms of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery. J. Neurosurg. 1982;57(3):418–422. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.3.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan M.K., Besser M., Johnston I., Chaseling R. Intracranial carotid artery injury in closed head trauma. J. Neurosurg. 1987;66(2):192–197. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.2.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokri B., Piepgras D.G., Houser O.W. Traumatic dissections of the extracranial internal carotid artery. J. Neurosurg. 1988;68(2):189–197. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.2.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watridge C.B., Muhlbauer M.S., Lowery R.D. Traumatic carotid artery dissection: diagnosis and treatment. J. Neurosurg. 1989;71(6):854–857. doi: 10.3171/jns.1989.71.6.0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mokri B. Traumatic and spontaneous extracranial internal carotid artery dissections. J. Neurol. 1990;237(6):356–361. doi: 10.1007/BF00315659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reddy K., Furer M., West M., Hamonic M. Carotid artery dissection secondary to seatbelt trauma: case report. J. Trauma. 1990;30(5):630–633. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199005000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pica R.A.J., Jr, Rockwell B.H., Raji M.R., Dastur K.J., Berkey K.E. Traumatic internal carotid artery dissection presenting as delayed hemilingual paresis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1996;17(1):86–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duke B.J., Ryu R.K., Coldwell D.M., Brega K.E. Treatment of blunt injury to the carotid artery by using endovascular stents: an early experience. J. Neurosurg. 1997;87(6):825–829. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuura J.H., Rosenthal D., Jerius H., Clark M.D., Owens D.S. Traumatic carotid artery dissection and pseudoaneurysm treated with endovascular coils and stent. J. Endovasc. Surg. 1997;4(4):339–343. doi: 10.1583/1074-6218(1997)004<0339:TCADAP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babovic S., Zietlow S.P., Garrity J.A., Kasperbauer J.L., Bower T.C., Bite U. Traumatic carotid artery dissection causing blindness. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2000;75(3):296–298. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)65037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jariwala S.P., Crowley J.G., Roychowdhury S. Trauma-induced extracranial internal carotid artery dissection leading to multiple infarcts in a young girl. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2006;22(10):737–742. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000236835.46818.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan M.A., Dowd N., Rawluk D., Cunningham A.J. Traumatic bilateral internal carotid artery dissection following airbag deployment in a patient with fibromuscular dysplasia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000;85(3):476–478. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uhrenholt L., Freeman M.D., Webb A.L., Pedersen M., Boel L.W. Fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with internal carotid artery dissection resulting from whiplash trauma. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2015;11(4):564–569. doi: 10.1007/s12024-015-9715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fusonie G.E., Edwards J.D., Reed A.B. Covered stent exclusion of blunt traumatic carotid artery pseudoaneurysm: case report and review of the literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2004;18(3):376–379. doi: 10.1007/s10016-004-0037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simionato F., Righi C., Scotti G. Post-traumatic dissecting aneurysm of extracranial internal carotid artery: endovascular treatment with stenting. Neuroradiology. 1999;41(7):543–547. doi: 10.1007/s002340050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Wessem K.J., Meijer J.M., Leenen L.P., van der Worp H.B., Moll F.L., de Borst G.J. Blunt traumatic carotid artery dissection still a pitfall? The rationale for aggressive screening. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2011;37(2):147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00068-010-0032-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fanelli F., Salvatori F.M., Ferrari R., Pacella S., Rossi P., Passariello R. Stent repair of bilateral post-traumatic dissections of the internal carotid artery. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2004;11(4):517–521. doi: 10.1583/04-1207.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crönlein M., Sandmann G.H., Beirer M., Wunderlich S., Biberthaler P., Huber-Wagner S. Traumatic bilateral carotid artery dissection following severe blunt trauma: a case report on the difficulties in diagnosis and therapy of an often overlooked life-threatening injury. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2015;20:62. doi: 10.1186/s40001-015-0153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ariyada K., Shibahashi K., Hoda H., Watanabe S., Nishida M., Hanakawa K., Murao M. Bilateral internal carotid and left vertebral artery dissection after blunt trauma: A case report and literature review. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 2019;59(4):154–161. doi: 10.2176/nmc.cr.2018-0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busch T., Aleksic I., Sirbu H., Kersten J., Dalichau H. Complex traumatic dissection of right vertebral and bilateral carotid arteries: a case report and literature review. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000;8(1):72–74. doi: 10.1016/S0967-2109(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fateri F., Groebli Y., Rüfenacht D.A. Intraarterial thrombolysis and stent placement in the acute phase of blunt internal carotid artery trauma with subocclusive dissection and thromboembolic complication: case report and review of the literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2005;19(3):434–437. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-0023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gouny P., Nowak C., Smarrito S., Fadel E., Hocquet-Cheynel C., Nussaume O. Bilateral thrombosis of the internal carotid arteries after a closed trauma. Advantages of magnetic resonance imaging and review of the literature. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. (Torino) 1998;39(4):417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griessenauer C.J., Foreman P.M., Deveikis J.P., Harrigan M.R. Optical coherence tomography of traumatic aneurysms of the internal carotid artery: report of 2 cases. J. Neurosurg. 2016;124(2):305–309. doi: 10.3171/2015.1.JNS142840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laitt R.D., Lewis T.T., Bradshaw J.R. Blunt carotid arterial trauma. Clin. Radiol. 1996;51(2):117–122. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(96)80268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lemmerling M., Crevits L., Defreyne L., Achten E., Kunnen M. Traumatic dissection of the internal carotid artery as unusual cause of hypoglossal nerve dysfunction. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 1996;98(1):52–54. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(95)00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malek A.M., Higashida R.T., Phatouros C.C., Lempert T.E., Meyers P.M., Smith W.S., Dowd C.F., Halbach V.V. Endovascular management of extracranial carotid artery dissection achieved using stent angioplasty. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2000;21(7):1280–1292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Men S., Oztürk H., Hekimoğlu B., Sekerci Z. Traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula treated by combined transarterial and transvenous coil embolization and associated cavernous internal carotid artery dissection treated with stent placement. Case report. J. Neurosurg. 2003;99(3):584–586. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petetta C., Santovito D., Tattoli L., Melloni N., Bertoni M., Di Vella G. Forensic and clinical issues in a case of motorcycle blunt trauma and bilateral carotid artery dissection. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020;64:409.e11–409.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prasad V., Gandhi D., Jindal G. Pipeline endovascular reconstruction of traumatic dissecting aneurysms of the intracranial internal carotid artery. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013010899. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-010899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scavée V., De Wispelaere J.F., Mormont E., Coulier B., Trigaux J.P., Schoevaerdts J.C. Pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery: treatment with a covered stent. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2001;24(4):283–285. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stager V., Gandhi R., Stroman D., Timaran C., Broker H. Traumatic internal carotid artery injury treated with overlapping bare metal stents under intravascular ultrasound guidance. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;53(2):483–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taoussi N., Alghamdi A.J., Bielewicz J., Luchowski P., Rejdak K. Traumatic bilateral dissection of cervical internal carotid artery in the wake of a car accident: A case report. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2017;51(5):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.pjnns.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang G.M., Xue H., Guo Z.J., Yu J.L. Cerebral infarct secondary to traumatic internal carotid artery dissection. World J. Clin. Cases. 2020;8(20):4773–4784. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin R.F., Eldrup-Jorgensen J., Clark D.E., Bredenberg C.E. Blunt trauma to the carotid arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 1991;14(6):789–793. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.32076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Achtereekte H.A., van der Kruijk R.A., Hekster R.E., Keunen R.W. Diagnosis of traumatic carotid artery dissection by transcranial Doppler ultrasound: case report and review of the literature. Surg. Neurol. 1994;42(3):240–244. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90270-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Borst G.J., Slieker M.G., Monteiro L.M., Moll F.L., Braun K.P. Bilateral traumatic carotid artery dissection in a child. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006;34(5):408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fletcher J., Davies P.T., Lewis T., Campbell M.J. Traumatic carotid and vertebral artery dissection in a professional jockey: a cautionary tale. Br. J. Sports Med. 1995;29(2):143–144. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.29.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keilani Z.M., Berne J.D., Agko M. Bilateral internal carotid and vertebral artery dissection after a horse-riding injury. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52(4):1052–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alimi Y., Di Mauro P., Tomachot L., Albanese J., Martin C., Alliez B., Juhan C. Bilateral dissection of the internal carotid artery at the base of the skull due to blunt trauma: incidence and severity. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1998;12(6):557–565. doi: 10.1007/s100169900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Romner B., Sjöholm H., Brandt L. Transcranial Doppler sonography, angiography and SPECT measurements in traumatic carotid artery dissection. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 1994;126(2-4):185–191. doi: 10.1007/BF01476431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blanco Pampín J., Morte Tamayo N., Hinojal Fonseca R., Payne-James J.J., Jerreat P. Delayed presentation of carotid dissection, cerebral ischemia, and infarction following blunt trauma: two cases. J. Clin. Forensic Med. 2002;9(3):136–140. doi: 10.1016/S1353-1131(02)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chokyu I., Tsumoto T., Miyamoto T., Yamaga H., Terada T., Itakura T. Traumatic bilateral common carotid artery dissection due to strangulation. A case report. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2006;12(2):149–154. doi: 10.1177/159101990601200209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clarot F., Vaz E., Papin F., Proust B. Fatal and non-fatal bilateral delayed carotid artery dissection after manual strangulation. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005;149(2-3):143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duane T.M., Parker F., Stokes G.K., Parent F.N., Britt L.D. Endovascular carotid stenting after trauma. J. Trauma. 2002;52(1):149–153. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200201000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Molacek J., Baxa J., Houdek K., Ferda J., Treska V. Bilateral post-traumatic carotid dissection as a result of a strangulation injury. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2010;24(8):1133.e9–1133.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Flaherty P.M., Flynn J.M. Horner syndrome due to carotid dissection. J. Emerg. Med. 2011;41(1):43–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hughes K.M., Collier B., Greene K.A., Kurek S. Traumatic carotid artery dissection: a significant incidental finding. Am. Surg. 2000;66(11):1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lo Y.L., Yang T.C., Liao C.C., Yang S.T. Diagnosis of traumatic internal carotid artery injury: the role of craniofacial fracture. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2007;18(2):361–368. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e318033605f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Correa E., Martinez B. Traumatic dissection of the internal carotid artery: simultaneous infarct of optic nerve and brain. Clin. Case Rep. 2014;2(2):51–56. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gabriel S.A., Beteli C.B., Aluize de Menezes E., Gonçalves A.C., Gonçalves G.L., Marcinkevicius J.A., Nascimento L.M., Capelin P.R.M. Bilateral traumatic internal carotid artery dissection after crossfit training. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019;61:466.e1–466.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hostettler C., Williams T., McKnight C., Sanchez A., Diggs G. Traumatic carotid artery dissection. Mil. Med. 2013;178(1):e141–e145. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schievink W.I., Atkinson J.L., Bartleson J.D., Whisnant J.P. Traumatic internal carotid artery dissections caused by blunt softball injuries. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16(2):179–182. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(98)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kalantzis G., Georgalas I., Chang B.Y., Ong C., El-Hindy N. An Unusual Case of Traumatic Internal Carotid Artery Dissection during Snowboarding. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014;13(2):451–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taşcılar N., Ozen B., Açıkgöz M., Ekem S., Acıman E., Gül S. Traumatic internal carotid artery dissection associated with playing soccer: a case report. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17(4):371–373. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2011.60134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fridley J., Mackey J., Hampton C., Duckworth E., Bershad E. Internal carotid artery dissection and stroke associated with wakeboarding. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2011;18(9):1258–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou W., Huynh T.T., Kougias P., El Sayed H.F., Lin P.H. Traumatic carotid artery dissection caused by bungee jumping. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007;46(5):1044–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pary L.F., Rodnitzky R.L. Traumatic internal carotid artery dissection associated with taekwondo. Neurology. 2003;60(8):1392–1393. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000055924.12065.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar S.D., Kumar V., Kaye W. Bilateral internal carotid artery dissection from vomiting. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16(7):669–670. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(98)90172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee W.W., Jensen E.R. Bilateral internal carotid artery dissection due to trivial trauma. J. Emerg. Med. 2000;19(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vadikolias K., Heliopoulos J., Serdari A., Vadikolia C.M., Piperidou C. Flapping of the dissected intima in a case of traumatic carotid artery dissection in a jackhammer worker. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2009;37(4):221–222. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alimi Y.S., Di Mauro P., Fiacre E., Magnan J., Juhan C. Blunt injury to the internal carotid artery at the base of the skull: six cases of venous graft restoration. J. Vasc. Surg. 1996;24(2):249–257. doi: 10.1016/S0741-5214(96)70100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fuse T., Ichihasi T., Matuo N. Asymptomatic carotid artery dissection caused by blunt trauma. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo) 2008;48(1):22–25. doi: 10.2176/nmc.48.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pezzini A., Hausser I., Brandt T., Padovani A., Grond-Ginsbach C. Internal carotid artery dissection after French horn playing. Spontaneous or traumatic event? J. Neurol. 2003;250(8):1004–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-1150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vishteh A.G., Marciano F.F., David C.A., Schievink W.I., Zabramski J.M., Spetzler R.F. Long-term graft patency rates and clinical outcomes after revascularization for symptomatic traumatic internal carotid artery dissection. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(4):761–767. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199810000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McNeil J.D., Chiou A.C., Gunlock M.G., Grayson D.E., Soares G., Hagino R.T. Successful endovascular therapy of a penetrating zone III internal carotid injury. J. Vasc. Surg. 2002;36(1):187–190. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.125020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]