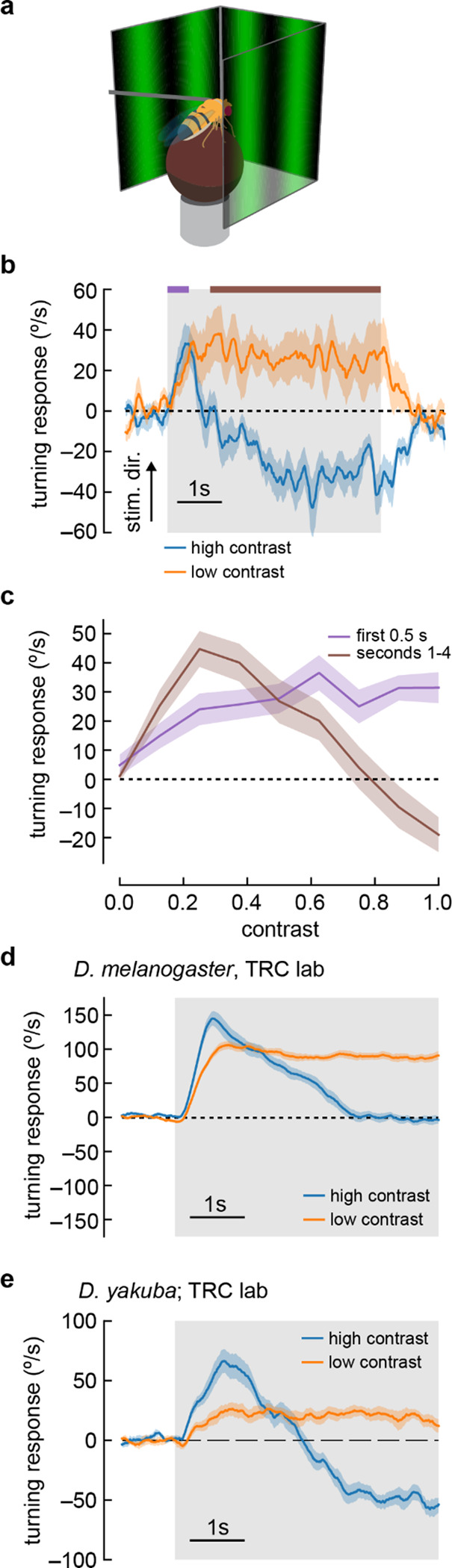

Figure 1. Flies turn opposite to the stimulus direction in high contrast conditions.

a) We measured fly turning behavior as they walked on an air-suspended ball. Stimuli were presented over 270 degrees around the fly.

b) We presented drifting sinusoidal gratings for 5 seconds (shaded region) with either high contrast (c = 1.0) or low contrast (c = 0.25). When high contrast sinusoidal gratings were presented, flies initially turned in the same direction as the stimulus, then started turning in the opposite direction after ~1 second of stimulation. Under low contrast conditions, flies turned continuously in the same direction as the stimulus. In these experiments, the sine waves had a wavelength of 60° and a temporal frequency of 1 Hz. Shaded patches represent ±1 SEM. N= 10 flies.

c) We swept contrast between 0 and 1 and measured the mean turning response during the first 0.5 seconds (purple, purple bar in b) and during the last 4 seconds of the stimulus (brown, brown line in b). The response in the first 0.5 seconds increased with increasing contrast, while the response in the last four seconds increased from c = 0 to c = 0.25, and then decreased with increasing contrast, until flies turned in the direction opposite the stimulus direction at the highest contrasts. N = 20 flies.

d) We repeated the presentation of drifting sinusoidal gratings, this time in the lab of author TRC, using a similar behavioral apparatus. Stimulus parameters were as described in (b). In these experiments, the population average shows that flies proceeded to zero net turning at high contrasts, but some individual flies exhibited anti-directional turning responses. N = 20 flies.

e) We repeated the experiments with D. yakuba, also in the lab of TRC, and observed that this species exhibited a robust anti-directional turning response to high contrast gratings and a classical syn-directional turning response to low contrast gratings. N = 11 flies.