Abstract

Background

Circulating omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) have been associated with various chronic diseases and mortality, but results are conflicting. Few studies examined the role of a balanced omega-6/omega-3 ratio in mortality.

Methods

We investigated plasma omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs and their ratio in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a large prospective cohort, the UK Biobank. Of 117,546 participants who had complete information on circulating PUFAs, 4,733 died during follow-up, including 2,585 from cancer and 1,017 from cardiovascular disease (CVD). Associations were estimated by multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression with adjustment for relevant risk factors.

Results

Results: Risk for all three mortality outcomes increased as the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs increased (all Ptrend < 0.001). Comparing the highest to the lowest quintiles, individuals had 42% (95% CI, 28–57%) higher total mortality, 31% (95% CI, 13–50%) higher cancer mortality, and 40% (95% CI, 12–75%) higher CVD mortality. Moreover, omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in plasma were all inversely associated with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality, with omega-3 showing stronger effects.

Conclusions

Using a population-based cohort in UK Biobank, our study revealed a strong association between the ratio of circulating omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs and the risk of all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality.

Keywords: Polyunsaturated fatty acids, Omega-3 fatty acids, Omega-6 fatty acids, Mortality, Prospective studies

Background

Cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are the two leading causes of non-communicable disease mortality globally1. Substantial epidemiologic evidence has linked the dietary or circulating levels of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to the risks of all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality (Additional file 1: Table S1). However, the results are inconsistent, especially for omega-6 PUFAs. Most large observational studies support the protective effects of omega-3 PUFAs. In addition to total and individual omega-3 PUFAs, the omega-3 index, defined as the percentage of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) in total fatty acids in red blood cells, was shown to be a validated biomarker of the dietary intake and tissue levels of long-chain omega-3 PUFAs, and was proposed to be a risk factor for CVD and related mortality2,3. While the omega-3 index has been observed to be inversely associated with all cause-mortality, its association patterns with CVD and cancer mortality are less clear4–6. Most importantly, results from clinical trials of omega-3 PUFA supplementation have been inconsistent7,8. On the other hand, while some studies revealed inverse associations of omega-6 PUFAs with all-cause mortality9–11, others reported null results4,12–15. The role of omega-6 PUFAs in cancer and CVD mortality is less studied, and the patterns are similarly conflicting4,9–11. Interpreting previous observational results is challenging due to the limitations of small sample sizes, insufficient adjustments for confounding, and unique sample characteristics. Moreover, many studies rely on self-reported dietary intake or fish oil supplementation status, which are subject to large variability and reporting bias16. Despite the tremendous interest and research effort, the roles of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in all-cause and cause-specific mortality remain controversial.

It has been suggested that the high omega-6/omega-3 ratio in Western diets, 20:1 or even higher, as compared to an estimated 1:1 during the most time of human evolution, contributes to many chronic diseases, including CVD, cancer, and autoimmune disorders17,18. However, while many previous studies have examined total or individual omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, fewer investigated the role of their imbalance, as measured by the omega-6/omega-3 ratio, in mortality4,14,15,19. In a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal women, the omega-6/omega-3 ratio in red blood cells was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality but not with cancer or CVD mortality4. Similar positive associations with all-cause mortality were observed in smaller cohorts investigating the ratio in serum or dietary intake14,19. However, prospective studies in two independent cohorts from China and US did not find a linear positive association between the omega-6/omega-3 ratio in diet and all-cause mortality15. To address these gaps in our understanding of the roles of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs and their imbalance in all-cause and cause-specific mortality, we perform a prospective study in a large population-based cohort (N = 117,546) from UK Biobank, using objective measurements of PUFA levels in plasma.

Methods

Study population

The UK Biobank study is a prospective, population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom20. Between 2006 and 2010, 502,536 prospective participants, aged 40–69, in 22 assessment Centers throughout the UK were recruited for the study. The population information was collected through a self-completed touch-screen questionnaire; brief computer-assistant interview; physical and functional measures; and blood, urine, and saliva collection during the assessment visit. Participants with incomplete data on the plasma omega-6/omega-3 ratio (n=383,692) and those who withdrew from the study (n=1,298) were excluded from this study, leaving 117,546 participants, 4,733 died during follow-up, including 2,585 from cancer and 1,017 from CVD.

Ascertainment of exposure

Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs were measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in plasma samples collected between 2007 and 201020–22.

Ascertainment of outcome

The date and cause of death were identified through the death registries of the National Health Service (NHS) Information Centre for participants from England and Wales and the NHS Centre Register Scotland for participants from Scotland20. At the time of the analysis (3 May 2022), mortality data were available up to 14 February 2018 for England and Wales and 31 December 2016 for Scotland. Therefore, follow-up time was calculated as the time between the date of entering the assessment Centre and this date, or the date of death, whichever happened first. The underlying cause of death was assigned and coded in vital registries according to the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision). CVD mortality was defined using codes I00-I99, and cancer mortality was defined using codes C00-D48.

Ascertainment of covariates

The baseline questionnaire included detailed information on several possible confounding variables: demographic factors (age, sex, assessment Centre, ethnicity), socioeconomic status (Townsend Deprivation Index), lifestyle habits (alcohol assumption, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), physical activity) and other supplementation (Fish-oil supplementation).

Statistical analysis

We summarized and compared the characteristics of the participants across quintiles of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio at baseline using descriptive statistics. Pearson’s Chi-squared test and ANOVA test were used to compare the demographic characteristics across quintiles, respectively, for categorical variables and continuous variables. To investigate associations of the ratio with cause-specific and all-cause mortality, we used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to calculate hazard ratios23 and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). The proportional hazards assumption was not violated based on Schoenfeld residuals. We analyzed the ratio as continuous and categorical variables (i.e., quintiles). For all trend tests, we used the median value of each quintile as a continuous variable in the models. Potential nonlinear associations were assessed semi-parametrically using restricted cubic splines (4 knots were used in regression splines)24.

Based on previous literature and biological plausibility11,25,26, we chose the following variables as covariates in the multivariate models: age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre, BMI (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol intake status (never, previous, current), physical activity (low, moderate, high).

In secondary analyses to assess potential differences in associations across different population subgroups, we repeated the above-described analyses stratified by age (< vs. ≥ the median age of 58 years), sex (male/female), Townsend deprivation index (< vs. ≥ the population median of −2), BMI ((< vs. ≥ 25), current smoking status (yes vs. no), and physical activity (low and moderate vs. high).

We also conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, to assess whether the associations of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio with mortality outcomes were primarily driven by omega-3 fatty acids or omega-6 fatty acids, we assessed both the separate and the joint associations of omega-3 fatty acids to total fatty acids percentage (omega-3%) and omega-6 fatty acids to total fatty acids percentage (omega-6%) with the three mortality outcomes. We also performed a joint analysis with categories of the omega-3% and omega-6% quintiles, using participants in both the lowest omega-3% and omega-6% quintiles as the reference category. An interaction term between omega-3% and omega-6% was included in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model, and a Wald test was used to assess its significance. The correlation between omega-3% and omega-6% was assessed by the Spearman correlation. Second, to address the potential residual confounding by fish oil supplementation, we further adjusted for the supplementation status from the baseline questionnaire. Third, to investigate the effects of missing values, we imputed missing values (<1% for most factors, up to 19% for physical activity) by chained equations and performed synthesis analyses on the imputed datasets27. Fourth, to assess whether the observed associations are attenuated by reverse causation, we excluded those who died in the first year of follow-up. Last, to assess the representativeness of the participants included in our study, we compared the baseline characteristics between the participants with and without exposure information. All P-values were two-sided. We considered a P-value ≤0.05 or a 95% confidence interval (CI) excluding 1.0 for HRs as statistically significant. We conducted all analyses using R, version 4.0.3.

Results

Baseline characteristics

In the analytic cohort of 117,546 participants, over a mean of 8.9 years of follow-up, 4,733 died, including 2,585 from cancer and 1,017 from CVD. The baseline characteristics of the participants across quintiles of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 were summarized in Table 1. Study participants were, on average, 57 years old and 91% White. Those in the higher ratio quintiles were more likely to be younger, male, and current smokers, but less likely to take fish oil supplementation.

Table 1.

Selected participant characteristics at baseline across quintiles of the plasma omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs ratio (n=117,546).

| Omega-6/omega-3 ratio quintiles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Characteristicsa | 1 (median = 5.8) (n = 23,504) | 2 (median = 7.5) (n = 23,504) | 3 (median = 9.0) (n = 23,510) | 4 (median = 10.8) (n = 23,516) | 5 (median = 14.6) (n = 23,512) | P |

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 59.2 (7.2) | 57.8 (7.7) | 56.4 (8.0) | 55.3 (8.2) | 53.9 (8.2) | <0.001b |

| Sex (male%) | 39.5 | 43.6 | 46.5 | 48.2 | 51.4 | <0.001c |

| Ethnicity(n%) | ||||||

| White | 21,193 (90.6) | 21,324 (91.1) | 21,407 (91.5) | 21,332 (91.2) | 21,273 (90.9) | 0.047c |

| Black | 144 (0.6) | 124 (0.5) | 127 (0.5) | 130 (0.6) | 146 (0.6) | |

| Asian | 888 (3.8) | 867 (3.7) | 866 (3.7) | 879 (3.8) | 902 (3.9) | |

| Others | 1,175 (5.0) | 1,092 (4.7) | 994 (4.2) | 1,054 (4.5) | 1,086 (4.6) | |

| Missing (n) | 104 | 97 | 116 | 121 | 105 | |

| BMI | 27.3 (4.4) | 27.6 (4.6) | 27.6 (4.8) | 27.5 (4.9) | 27.2 (5.1) | <0.001b |

| Missing (n) | 77 | 90 | 84 | 78 | 102 | |

| Smoking status (n%) | <0.001c | |||||

| Never | 12,890 (55.1) | 12,672 (54.2) | 12,875 (55.0) | 12,788 (54.7) | 12,605 (53.9) | |

| Previous | 8,971 (38.4) | 8,686 (37.1) | 8,201 (35.0) | 7,813 (33.4) | 7,018 (30.0) | |

| Current | 1,519 (6.5) | 2,025 (8.7) | 2,324 (9.9) | 2,786 (11.9) | 3,768 (16.1) | |

| Missing (n) | 124 | 121 | 110 | 129 | 121 | |

| Alcohol status (n%) | <0.001c | |||||

| Never | 895 (3.8) | 892 (3.8) | 953 (4.1) | 1059(4.5) | 1343 (5.7) | |

| Previous | 736 (3.1) | 752 (3.2) | 778 (3.3) | 841 (3.6) | 1161 (5.0) | |

| Current | 21,815 (93.0) | 21,817 (93.0) | 21,720 (92.6) | 21,552 (91.9) | 20,943 (89.3) | |

| Missing (n) | 58 | 43 | 59 | 64 | 65 | |

| Physical activity (n%) | <0.001c | |||||

| High | 7,634 (40.1) | 7,492 (39.3) | 7,518 (39.5) | 7,669 (40.5) | 7,984 (42.2) | |

| Moderate | 7,988 (41.9) | 7,909 (41.5) | 7,800 (41.0) | 7,624 (40.3) | 7,287 (38.5) | |

| Low | 3,430 (18.0) | 3,645 (19.1) | 3,715 (19.5) | 3,643 (19.2) | 3,640 (19.2) | |

| Missing (n) | 4,452 | 4,458 | 4,447 | 4,580 | 4,601 | |

| Fish oil supplementation (Yes%) | ||||||

| 48.6 | 38.1 | 30.4 | 23.8 | 15.9 | <0.001c | |

| Missing (n) | 73 | 64 | 97 | 106 | 97 | |

| Omega-3 percentage | 6.7 (1.4) | 5.0 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.4) | 3.6 (0.4) | 2.6 (0.5) | <0.001b |

| Omega-6 percentage | 36.1 (3.7) | 37.3 (3.5) | 38.1 (3.3) | 38.9 (3.2) | 40.1 (3.1) | <0.001b |

All variables measured at baseline are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

From the ANOVA test for continuous variables.

From the Pearson’s Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Main results

The associations of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio with all-cause and cause-specific mortality risks were presented in Table 2. A higher ratio was strongly associated with higher mortality from all causes, cancer, and CVD (Ptrend < 0.001 for all three). In the fully adjusted models that considered the ratio as a continuous variable, every unit increase in the ratio corresponded to 2%, 1%, and 2% higher risk in all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality, respectively. When comparisons were made between the highest and the lowest quintile of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio, there were 42%, 31%, and 40% increased risk for all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality, respectively.

Table 2.

Associationsa of the plasma omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs ratio with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank

| Omega ratio variable forms | Causes of death |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause |

Cancer |

Cardiovascular diseases |

|||||||

| Number of deaths | Partially adjusted associationsb | Fully adjusted associationsc | Number of deaths | Partially adjusted associationsb | Fully adjusted associationsc | Number of deaths | Partially adjusted associationsb | Fully adjusted associationsc | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Continuous | 4,733 | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | 2,585 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 1,017 | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

|

| |||||||||

| Quintiles (median) | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 1 (5.8) | 900 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 512 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 202 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 2 (7.5) | 896 | 1.07 (0.97–1.17) | 1.02 (0.91–1.13) | 539 | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 176 | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 0.87 (0.69–1.11) |

| 3 (9.0) | 868 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 469 | 1.06 (0.94–1.21) | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 187 | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) | 0.91 (0.72–1.16) |

| 4 (10.8) | 980 | 1.31 (1.20–1.44) | 1.26 (1.14–1.40) | 529 | 1.30 (1.15–1.47) | 1.26 (1.10–1.45) | 208 | 1.17 (0.96–1.42) | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) |

| 5 (14.6) | 1,089 | 1.55 (1.42–1.70) | 1.42 (1.28–1.57) | 533 | 1.42 (1.25–1.60) | 1.31 (1.13–1.50) | 244 | 1.42 (1.17–1.72) | 1.40 (1.12–1.75) |

| P trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazards ratio; ref, reference.

From Cox proportional hazards regression.

Adjusted for age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre.

Adjusted for age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre, BMI (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol intake status (never, previous, current), physical activity (low, moderate, high).

Stratified analysis

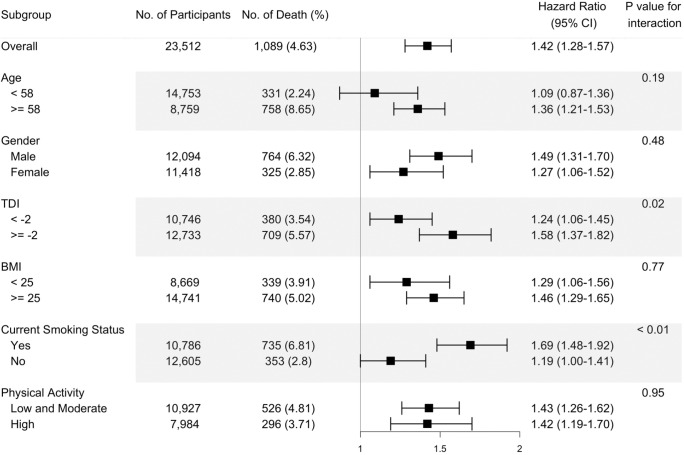

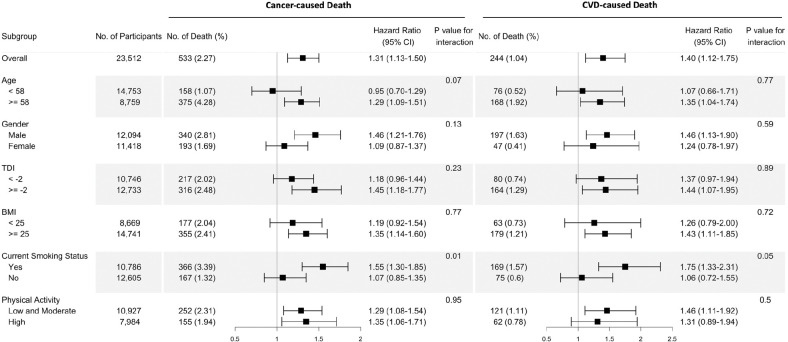

The fully adjusted associations of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio with all-cause mortality revealed that compared to the lowest quintile, the highest quintile has strong, statistically significant associations with elevated risk within all categories of sex, TDI, BMI, smoking status, and physical activity (Figure 1, Additional file 2: Table S2), except in those aged less than 58 years old. The estimated associations with all-cause mortality were stronger in current smokers and those with a higher TDI (P for interaction < 0.01 and = 0.02, respectively; Figure 1). For cancer and CVD mortality, they also tended to be stronger among current smokers (P for interaction = 0.01 and 0.05, respectively). No significant interactions were found for other risk factors (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Risk estimates of all-cause mortality for the highest compared with the lowest quintile of the ratio of plasma omega-6 to omega-3 PUFAs, stratified by potential risk factors. Results were adjusted for age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre, BMI (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol intake status (never, previous, current), physical activity (low, moderate, high).

Figure 2.

Risk estimates of cause-specific mortality for the highest compared with the lowest quintile of the ratio of plasma omega-6 to omega-3 PUFAs, stratified by potential risk factors. Results were adjusted for age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre, BMI (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol intake status (never, previous, current), physical activity (low, moderate, high).

Restricted cubic spline analysis

Restricted cubic spline analysis suggested significant positive associations of the omega6/omega-3 ratio with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality (P < 0.01 for all three outcomes, Figure 3). Potential nonlinearity in these positive associations was identified for all-cause mortality (P = 0.011) and CVD mortality (P = 0.011) but not for cancer mortality (P > 0.05). The strength of the relationship between the ratio and all-cause mortality appears to remain at a relatively low level before it starts to increase quickly after the ratio exceeds 8. A similar trend with higher uncertainties was observed for CVD mortality.

Figure 3. Associations of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs with all-cause and cause-specific mortality evaluated using restricted cubic splines. Hazard ratios and omega ratios are presented in the vertical and horizontal axis, respectively.

The best estimates and their confidence intervals are presented as solid red lines and dotted black lines, respectively. The ratio 4 was selected as a reference level, and the x-axis depicts the ratio from 0 to 40. Potential nonlinearity was identified for all-cause mortality (p =0.011) and CVD-caused mortality (p = 0.011), but not for cancer-caused mortality (p > 0.05). All HRs are adjusted for age (years; continuous), sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Asian, Others), Townsend deprivation index (continuous), assessment Centre, BMI (kg/m2; continuous), smoking status (never, previous, current), alcohol intake status (never, previous, current), physical activity (low, moderate, high).

Omega-3, Omega-6, and Joint analysis

We further performed analyses to assess whether the associations of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio with mortality outcomes were primarily driven by omega-3 or omega-6 fatty acids. The correlation between the omega-3% and omega-6% was relatively low with r = 0.12 (P < 0.01). Across all models, both the omega-3% and omega-6% were inversely associated with all three mortality outcomes (Ptrend < 0.001 for both exposures and all three outcomes, Additional file 2: Table S3 and Table S4). Notably, their associations remained significant when they were included in the same models. On the other hand, the effect sizes of the inverse associations were always bigger for the omega-3%. For example, when comparing those in the highest omega-3% quintile to the lowest quintile, the fully adjusted HRs (95% CI) for all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality were, respectively, 0.62 (0.55, 0.68), 0.68 (0.59, 0.79), and 0.62 (0.49, 0.78) (Additional file 2: Table S3). The corresponding HRs for the omega-6% were 0.81 (0.72, 0.90), 0.78 (0.67, 0.91), and 0.87 (0.67, 1.12) (Additional file 2: Table S4). Furthermore, in another joint analysis of the omega-3% and omega-6%, the lowest risk for all three mortality outcomes was observed among those in the joint highest categories of the two fatty acids (Additional file 2: Table S5). For example, when comparing those in the highest quintiles of the two fatty acids to the group with the joint lowest group, the HRs (95% CI) for all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality were, respectively, 0.46 (95% CI, 0.32, 0.66), 0.41 (95% CI, 0.25, 0.68), and 0.77 (95% CI, 0.36, 1.64).

Other sensitivity analyses

After further adjustment of the fish oil supplementation status, the associations between the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 and mortality outcomes were slightly attenuated yet did not alter the main findings (Additional file 2: Table S6). Our primary analysis excluded participants with missing information (i.e., a complete-case analysis). We performed a sensitivity analysis using the multiply-imputed datasets, and there were no substantial changes (Additional file 2: Table S7). Moreover, the exclusion of participants who died during their first-year follow-up did not materially alter the results (Additional file 2: Table S8). The baseline characteristics are comparable between participants with or without exposure information (Additional file 2: Table S9).

Discussion

In this prospective population-based study of UK individuals, we showed that a higher ratio of plasma omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids was positively associated with the risk of all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality. These associations were independent of most risk factors examined, including age, sex, BMI, and physical activity, but they were all stronger in current smokers. These relationships were linear for cancer mortality but not for all-cause and CVD mortality. For those two outcomes, the risk of mortality first decreased at lower ratios and then increased, with an inflection point around the ratio of 8. Moreover, omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs in plasma were consistently and inversely associated with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality, with omega-3 showing stronger effects.

To date, studies that examined the relationship between the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs and mortality in the general population are sparse4,14,15,19. Similar to our finding, in a 2017 report from a prospective women cohort study (n=6,501; 1,875 all-cause deaths, 617 CVD deaths, 462 cancer deaths)4, the adjusted HR for all-cause mortality was 1.10 (1.02–1.19) per 1-SD increase of omega-6/omega-3 ratio in red blood cells, however, the effects were not significant for cancer and CVD deaths. Another study supporting our results was conducted on elderly Japanese individuals (n=1,054; 422 deaths). It found that the ratio of an omega-3 fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, to an omega-6 fatty acid, arachidonic acid (ARA), is inversely associated with all-cause mortality, with an HR of 0.71 (95% 0.53–0.96) comparing the highest to the lowest tertile14. Findings of previous studies based on dietary intake were null15,19. A prospective cohort involving 145 hemodialysis patients enrolled in Southern California during 2001–2007 (42 all-cause deaths) showed that the estimated HR (95% CI) for all-cause mortality among those in the lowest relative to the highest quartiles of dietary omega-6/omega-3 ratio was 0.37 (0.14–1.08)19. Although the effect was not significant, it still shows the protective trend of a lower omega-6/omega-3 ratio against premature death, when taking the sample size and study population into consideration. In a 2019 report based on two population-based prospective cohorts in China (n=14,117, 1,007 all-cause deaths) and the US (n=36,032, 4,826 all-cause deaths), the effect of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio intake was not significant (HR (95% CI) is 0.95 (0.80–1.14) for China and 0.99 (0.89–1.11) for US, respectively)15. These discrepancies may be explained by the usage of circulating biomarkers or dietary intakes for calculating the omega-6/omega-3 ratio. The estimated dietary intakes may be inaccurate due to recall bias or outdated food databases16. The circulating level is a more objective measurement of PUFA status and thus provides a more reliable picture of the effects of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs on mortality.

A large number of existing observational studies documented the reverse association of circulating levels and intake of omega-3 PUFAs with mortality5,6,26,28–33, which is in line with our finding that individuals in the highest quintile of the omega-6/omega-3 ratio had approximately 40% higher risk for all-cause and CVD mortality and 30% higher risk for cancer mortality, when compared to those in the lowest quintile. Few previous studies have examined the association in generally healthy populations6,26,28,30. In a 2016 meta-analysis30 of seven epidemiologic studies for dietary omega-3 PUFAs intake and four studies for circulating levels, the estimated relative risk for all-cause mortality was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.84–0.98) when comparing the highest to the lowest categories of omega-3 PUFA intake. In two 2018 reports of population-based studies in the US, the circulating level and dietary intake of omega-3 PUFAs were significantly associated with lower total mortality6,26. In a 2021 meta-analysis of 17 epidemiologic studies, comparing the highest to the lowest quintiles of circulating EPA and DHA, the estimated HRs for all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality were 0.84 (0.79–0.89), 0.80 (0.73–0.88) and 0.87 (0.78–0.96), respectively28. Moreover, inverse associations of omega-3 PUFAs biomarkers with total mortality were found in patients with myocardial infarction31,32, type 2 diabetes12, and other diseases5,29,33,34; inverse associations of omega-3 PUFAs with CVD mortality were also reported in these patient groups5,12,31. However, there are also reports of a null relationship between omega-3 PUFAs and mortality13,14,35. One possible explanation for the discrepancies could be the limited statistical power due to the small sample size and the small number of events. Moreover, the inconsistency may be due to unique sample characteristics; one study only involved elder patients14, and one only involved women35.

A smaller number of studies have evaluated the associations of omega-6 PUFAs with mortality. Our findings in the large UK prospective cohort are in accordance with the results of several previous studies that increased circulating levels of omega-6 PUFAs were associated with decreased all-cause mortality9,11,15,36. Moreover, a 2019 meta-analysis involving 18 cohort studies and 12 case-control studies showed that an omega-6 PUFA, linoleic acid, was inversely associated with CVD mortality; the HR per interquintile range was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.70–0.85)10. Other studies, however, did not support such reverse associations4,12–14,35. Although the findings were inconsistent, no previous studies reported harmful effects of omega-6 PUFAs on mortality4,11–15,35–38. Our studies support the protective effects of omega-6 PUFAs on all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Further research is needed to investigate the health impacts of omega-6 PUFAs in laboratory studies, epidemiological investigations, and clinical trials.

Strengths of our current study include the use of objective PUFA biomarkers in plasma instead of the estimated intakes from dietary questionnaires, which increases the accuracy of exposure assessment. Moreover, the prospective population-based study design, large sample size, long duration of follow-up, and detailed information on potential confounding variables, substantially mitigate the possible complications from reverse causality and confounding bias. In several sensitivity analyses, most of the documented associations remain materially unchanged, indicating the robustness of our results.

Several potential limitations deserve attention. First, plasma omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs were measured only once at baseline. Their levels may vary with diet or other lifestyle factors, which could cause misclassification over follow-up. However, some studies demonstrated that multiple measurements of omega-3 PUFAs have been consistent for a 6-month period39. Moreover, the 13-year within-person correlation for circulating omega-6 PUFAs was comparable to such correlations for other major CVD risk factors40. Thus, the single measurement of PUFAs at baseline, although not perfect, provides us with adequate information to investigate the relative long-term effects. Second, although we adjusted for many potential confounders in the model, we cannot rule out the imprecisely measured and unmeasured factors. Third, we did not analyze the individual omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs due to their unavailability in the NMR-based metabolomics data. Future studies should investigate the effects of specific individual PUFAs on all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Last, although we included individuals of different ancestries in the analysis, over 90% of the participants were of European ancestry. The generalizability of our findings across ancestries requires future verification.

Conclusions

In this large prospective cohort study, we documented robust positive associations of the plasma omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids ratio with the risk of all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality. Moreover, we found that plasma omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs were independently and inversely associated with the three mortality outcomes, with omega-3 fatty acids showing stronger protective effects. Our findings support the active management of a high circulating level of omega-3 fatty acids and a low omega-6/omega-3 ratio to prevent premature death.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 48818. We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the UK Biobank participants and administrative staff.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institute of Health under the award number R35GM143060 (KY). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- BMI

Body mass index

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DHA

Docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- HR

Hazard ratio

- Omega-3%

Omega-3 fatty acids to total fatty acids percentage

- Omega-6%

Omega-6 fatty acids to total fatty acids percentage

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- Ref

Reference

- SD

Standard deviation

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The UK Biobank received ethical approval from the research ethics committee (reference ID: 11/NW/0382). Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Literature review.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Risk estimates of ratio of plasma omega-6 to omega-3 PUFAs with all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality, stratified by potential risk factors, in the UK Biobank Study. Table S3. Associations of plasma omega-3 PUFAs percentage with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank Study. Table S4. Associations of plasma omega-6 PUFAs percentage with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank Study. Table S5. Fully adjusted joint associations of plasma omega-3 PUFAs percentage and omega-6 PUFAs percentage with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the UK Biobank Study. Table S6. Associations of ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank, covariates including fish oil supplementation status. Table S7. Associations of ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank Study, with multiple imputation for missing data. Table S8. Associations of ratio of omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs with all-cause, cancer, and CVD mortality risk in the UK Biobank Study, excluding those who died in the first follow-up year. Table S9. Baseline characteristics of participants with missing exposure information and not included in the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the UK Biobank through an application process (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

References

- 1.Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris WS, Von Schacky C. The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Prev Med. 2004;39(1):212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris WS. The omega-3 index: from biomarker to risk marker to risk factor. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2009;11(6):411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris WS, Luo J, Pottala JV, et al. Red blood cell polyunsaturated fatty acids and mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(1):250–259.e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleber ME, Delgado GE, Lorkowski S, März W, von Schacky C. Omega-3 fatty acids and mortality in patients referred for coronary angiography. The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Atherosclerosis. 2016;252:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris WS, Tintle NL, Etherton MR, Vasan RS. Erythrocyte long-chain omega-3 fatty acid levels are inversely associated with mortality and with incident cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(3):718–727.e716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Icosapent Ethyl for Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(1):11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicholls SJ, Lincoff AM, Garcia M, et al. Effect of high-dose omega-3 fatty acids vs corn oil on major adverse cardiovascular events in patients at high cardiovascular risk: the STRENGTH randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(22):2268–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado GE, März W, Lorkowski S, von Schacky C, Kleber ME. Omega-6 fatty acids: opposing associations with risk-The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11(4):1082–1090.e1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marklund M, Wu JHY, Imamura F, et al. Biomarkers of dietary omega-6 fatty acids and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality. Circulation. 2019;139(21):2422–2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu JHY, Lemaitre RN, King IB, et al. Circulating omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and total and cause-specific mortality. Circulation. 2014;130(15):1245–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris K, Oshima M, Sattar N, et al. Plasma fatty acids and the risk of vascular disease and mortality outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from the ADVANCE study. Diabetologia. 2020;63(8):1637–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura K, Hughes MCB, Ungerer JPJ, Green AC. Plasma eicosapentaenoic acid is negatively associated with all-cause mortality among men and women in a population-based prospective study. Nutr Res. 2016;36(11):1202–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otsuka R, Tange C, Nishita Y, et al. Fish and meat intake, serum eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid levels, and mortality in community-dwelling Japanese older persons. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang P, Wang W, Wang J, Zhang Y, Jiao J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids intake, omega-6/omega-3 ratio and mortality: Findings from two independent nationwide cohorts. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(2):848–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim JS, Oh K, Kim HC. Dietary assessment methods in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simopoulos AP. Evolutionary aspects of diet and essential fatty acids. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;88:18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233(6):674–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noori N, Dukkipati R, Kovesdy CP, et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid, ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 intake, inflammation, and survival in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J of Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):248–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: An Open Access Resource for Identifying the Causes of a Wide Range of Complex Diseases of Middle and Old Age. PLOS Medicine. 2015;12(3):e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julkunen H, Cichońska A, Slagboom PE, Würtz P, Nightingale Health UKBI. Metabolic biomarker profiling for identification of susceptibility to severe pneumonia and COVID-19 in the general population. eLife. 2021;10:e63033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Würtz P, Kangas AJ, Soininen P, Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Ala-Korpela M. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in large-scale epidemiology: a primer on -Omic technologies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(9):1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chua ME, Sio MCD, Sorongon MC, Dy JS. Relationship of Dietary Intake of Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids with Risk of Prostate Cancer Development: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies and Review of Literature. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:826254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8(5):551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z-H, Zhong W-F, Liu S, et al. Associations of habitual fish oil supplementation with cardiovascular outcomes and all cause mortality: evidence from a large population based cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Zhuang P, He W, et al. Association of fish and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids intakes with total and cause-specific mortality: prospective analysis of 421 309 individuals. J Intern Med. 2018;284(4):399–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris WS, Tintle NL, Imamura F, et al. Blood n-3 fatty acid levels and total and cause-specific mortality from 17 prospective studies. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindberg M, Saltvedt I, Sletvold O, Bjerve KS. Long-chain n-3 fatty acids and mortality in elderly patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(3):722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen GC, Yang J, Eggersdorfer M, Zhang W, Qin LQ. N-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of all-cause mortality among general populations: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pertiwi K, Küpers LK, Goede Jd, Zock PL, Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM. Dietary and circulating long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and mortality risk after myocardial infarction: a long-term follow-up of the Alpha Omega Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(23):e022617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S-H, Shin M-J, Kim J-S, et al. Blood eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid as predictors of all-cause mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction-data from Infarction Prognosis Study (IPS) Registry. Circ J. 2009;73(12):2250–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eide IA, Dahle DO, Svensson M, et al. Plasma levels of marine n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular risk markers in renal transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(7):824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pottala JV, Garg S, Cohen BE, Whooley MA, Harris WS. Blood eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids predict all-cause mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the Heart and Soul study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(4):406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miura K, Hughes MCB, Ungerer JPJ, Smith DD, Green AC. Absolute versus relative measures of plasma fatty acids and health outcomes: example of phospholipid omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and all-cause mortality in women. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57(2):713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warensjö E, Sundström J, Vessby B, Cederholm T, Risérus U. Markers of dietary fat quality and fatty acid desaturation as predictors of total and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(1):203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Salen P, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994;343(8911):1454–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petrone AB, Weir N, Hanson NQ, et al. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk of heart failure in the Physicians’ Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;97(1):66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Kawabata T, Hasegawa K, Akabane M, Tsugane S. Single measurement of serum phospholipid fatty acid as a biomarker of specific fatty acid intake in middle-aged Japanese men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(8):643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, et al. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150(4):341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the UK Biobank through an application process (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).