Abstract

Spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]diones and spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]diones were efficiently synthesized via one-pot multi-component reactions under ultrasound-promoted conditions. Spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]dione derivatives were successfully developed by the reaction of isatins, naphthalene-1-amine and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds. The spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]dione derivatives were prepared by the reaction of isatins, 5-amino-1-methyl-3-pheylpyrazole, and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds by using ( ±)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid as a catalyst in H2O/EtOH (3:1 v/v) solvent mixture. The antibacterial activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated against, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans. Compounds 4b, 4h, and 6h showed the strongest antimicrobial activity toward both bacteria. The MIC values of these compounds ranged from 375–3000 µg/mL. The effect of these compounds (4b, 4h, 6h) as a function of applied dose and time was investigated by a kinetic study, and the interaction with these antimicrobial results was simulated by a molecular docking study. We also used the docking approach with Covid-19 since secondary bacterial infections. Docking showed that indoline-quinoline hybrid compounds 4b and 4h exerted the strongest docking binding value against the active sites of 6LU7. In addition, the synthesized compounds had a moderate to good free radical scavenging activity.

Subject terms: Chemistry, Organic chemistry, Chemical synthesis

Introduction

Multicomponent reactions are valuable organic reactions in which three or more reactants react in a one-pot process to produce a final product1. These reactions have tremendous efficiency, especially for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds that exhibit a wide range of biological activities2. Multicomponent reactions comply with the principles of green chemistry in terms of a high degree of atom economy, easier progress of reactions, low energy consumption, short reaction times, and lack of waste products3.

Quinoline and indole are importat moieties of a large number of natural products and biologically active compounds4–7. Quinoline derivatives were found to have anticancer8, anti-HIV9, antibacterial10, antimalarial11, anti-inflammatory12 activities. Indole derivatives also exhibit antimicrobial13, antibacterial14, anti-inflammatory15, antiviral16, antidiabetic17, antitumor18, and anticancer19 activities. The spiro-fuced oxindole moiety is also a significant core structure of many pharmacological agents and natural products20–23 and additionally has also been shown to be a potential fluorescent materials24,25. On the other hand heterocylic compounds containing a pyrazole moiety exhibit anti-HIV26, anticancer27,28, antifungal29, and antimicrobial30–32 activities. Due to the broad biological activities of these spiro-fuced oxindole and pyrazole derivatives many synthetic methods for their preparation have been described33–43. In addition, various catalysts such as HOAc44, PTSA45, CAN46, L-Proline47, [NMP]H2PO448, ChCl/Lac49, Papain50, and Cu(OTf)251 have been used to promote this reaction.

The improvement of diverse synthetic processes that provide better environmental performance in synthetic organic chemistry is an objective52. Ultrasound irradiation promotes many organic reactions, owing to cavitational collapse. Various organic reactions can be effectively accomplished in higher yields, with shorter reaction times, and under milder reaction conditions using ultrasonic irradiation53–56.

(±)-Camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA) is an effective, water-soluble and reusable organocatalyst that has been used in various organic reactions. For instance, Friedel–Crafts reactions57, the synthesis of dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane58, and the synthesis of spirocyclic compounds59.

The aim of this work is to obtain spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]diones and spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]diones under ultrasonic irradiation in the presence of ( ±)-CSA catalyst in a H2O/EtOH solvent mixture (Figs. 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of compound 4a.

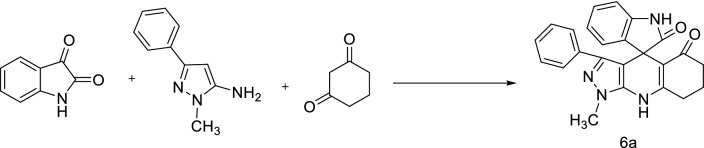

Figure 2.

Synthesis of compound 6a.

To extend the biological curiosity of the synthesized compounds, they were tested for their antibacterial activity against E. facealis, S. aureus, and C. albicans. The radical scavenging activity (determined by DPPH) of these compounds was also investigated. In general, effective HAT agents are compounds that have a high hydrogen atom donating ability and low heteroatom H-bond dissociation energy. Removal of hydrogen from these compounds results in C-centered radicals that are stabilized by resonance or the formation of sterically hindered radicals60. Co-infections in covid 19 pose a high risk, especially in intensive care units61. In this molecular docking study, S. aureus related biotin protein ligase, E. Facealis related alanine racemase, and protease N3 complex proteins of covid 19 were selected. In addition, molecular docking simulations were given chractersitics to show their mode of binding energy and the affection of these compounds against Sar-Cov-2 main protease inhibition62, Staphylococcus aureus biotin-protein ligase inhibitor63, and E.faecalis alanine racemase activity64.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The three-component reaction of isatin (1.00 mmol), 1,3-cyclohexadione (1.00 mmol), and naphthalene-1-amine (1.00 mmol) was used as a model reaction to optimize the reaction conditions. In the presence of %5 mol CSA in H2O compound 4a was obtained in 60 min with a yield of 26% under ultrasonic irradiation at room temperature. When the same reaction was examined in the same conditions in a H2O/EtOH (3:1, v/v) solvent mixture, the product was obtained with a yield of 74% in 45 min (Table 1).

Table 1.

Optimization of ( ±)-CSA catalyst loading in the synthesis of compound 4a.

| ( ±)-CSA (mol. %) | Temperature (°C) | Solvent | Conditions | Time (min) | Yield (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | 25 | EtOH | Stirring | 90 | Trace |

| 5 | 25 | H2O | Stirring | 90 | Trace |

| 5 | 25 | H2O | US | 60 | 26 |

| 5 | 25 | H2O/EtOH (3:1) | US | 45 | 74 |

| 5 | 50 | H2O/EtOH (3:1) | US | 30 | 88 |

| 10 | 50 | H2O/EtOH (3:1) | US | 30 | 89 |

When the temperature was increased to 50 °C the product was obtained in 88% yield, and the reaction was completed in 30 min (Table 1). A series of spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]diones were synthesized using the optimized reaction conditions under ultrasonic irradiation. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Synthesis of spiroquinoline-indoline-dione (Spirooxindole) derivatives in the presence of catalyst ( ±)-CSA.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Isatin/R | 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds | Product | Time (min) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | H | 1,3-Cyclohexanedione | 4a | 30 | 88 |

| 2 | H | 5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadione | 4b* | 30 | 84 |

| 3 | H | 1,3-Cyclopentanedione | 4c | 30 | 85 |

| 4 | H | 1,3-Indandione | 4d* | 30 | 89 |

| 5 | NO2 | 1,3-Cyclohexanedione | 4e | 30 | 85 |

| 6 | NO2 | 5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadione | 4f | 30 | 87 |

| 7 | NO2 | 1,3-Cyclopentanedione | 4g | 30 | 90 |

| 8 | NO2 | 1,3-Indandione | 4h* | 30 | 92 |

*These compounds were synthesized by another method in the literature44.

Then the spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]diones were synthesized via multicomponent reaction of isatins, 5-amino-1-methyl-3-pheylpyrazole, and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of %5 mol ( ±)-CSA in H2O/EtOH (3:1, v/v) under ultrasonic irradiation at 50 °C (Table 3).

Table 3.

Synthesis of spiropyrazolo-indoline-dione (Spirooxindole) derivatives in the presence of catalyst ( ±)-CSA.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Isatin/R | 1,3-Dicarbonyl compounds | Product | Time (min) | Yield (%) |

| 1 | H | 1,3-Cyclohexanedione | 6a | 30 | 84 |

| 2 | H | 5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadione | 6b | 30 | 87 |

| 3 | H | 1,3-Cyclopentanedione | 6c | 30 | 90 |

| 4 | H | 1,3-Indandione | 6d | 30 | 89 |

| 5 | NO2 | 1,3-Cyclohexanedione | 6e | 30 | 86 |

| 6 | NO2 | 5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadione | 6f | 30 | 85 |

| 7 | NO2 | 1,3-Cyclopentanedione | 6g | 30 | 91 |

| 8 | NO2 | 1,3-Indandione | 6h | 30 | 93 |

The structure of the synthesized compounds was confirmed by Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR), 1H NMR, 13C, NMR techniques and mass spectroscopy. The NH peaks were observed at 3600–3200 cm−1 and the C=O peaks were observed at 1730–1670 cm-1 in the FTIR spectra. In the 1H NMR spectra of compounds 4a–h and 6a–h, the aliphatic C–H protons resonated at δ 1.00–2.97 ppm and the aromatic C–H protons resonated at δ 6.40–8.75 ppm, and the N–H protons resonated t δ 9.35–11.40 ppm. In the 13C NMR spectra, the aliphatic carbons resonated at δ 18.50–53.00 ppm. The quareternery carbons in spiro moiety resonated at δ 47.00–55.00 ppm. The aromatic carbons resonated at δ 99.00–168.00 ppm. The carbonyl carbons resonated at δ 175.00–200.00 ppm. The mass spectra of all synthesized compounds exhibited the expected molecular ion peak.

Antimicrobial activity

The increasing resistance of microorganisms to antibiotics makes it necessary to synthesize compounds that can be used as antibiotics. For this reason, the research of compounds with antimicrobial properties has gained momentum in recent years65,66. In this part of the study, the antimicrobial activities of the synthesized spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]dione and spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]dione derivatives were investigated. For the antimicrobial studies, E. faecalis and S. aureus were used as bacteria and C. albicans as yeast samples. The stock solutions of all compounds used in this study were prepared in DMSO. It was found that some of the compounds showed significant antimicrobial effects (Table 4).

Table 4.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of complexes against wild-type microorganisms (μg/ml).

| Compound | Bacteria | Yeast | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51,299 | Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25,923 | Candida albicans ATCC 10,231 | |

| 4a | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 4b | 750 | 750 | > 6000 |

| 4c | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 4d | 3000 | 1500 | > 6000 |

| 4e | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 4f | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 4g | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 4h | 375 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6a | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6b | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6c | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6d | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6e | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6f | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6g | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| 6h | 3000 | 750 | > 6000 |

| DMSO | > 6000 | > 6000 | > 6000 |

| Gentamicin | > 256 | 4 | ND |

| Flucanozole | ND | ND | 32 |

When the MIC values of E. faecalis were examined, 4b and 4h showed significant antimicrobial activity. While the MIC value for 4b was 750 μg/mL, this value for 4h was found to be 375 μg/mL. As can be seen here, 4h has a stronger antimicrobial effect on E. faecalis than 4b. In addition, other compounds were found to have no antimicrobial effect on E.faecalis, but 4b and 4h had significant antimicrobial effect. MIC values were investigated for S. aureus, and it was found that these values ranged from 750 to > 6000 μg/ml. Among these compounds, mainly 4b and 4h were observed to have significant antimicrobial activity on S. aureus. The MIC values for 4b and 4h were determined to be 750 μg/mL. In addition to these results, no antimicrobial effect was observed for the MIC values of C. albicans.

Examination of the obtained results shows that 4b, 4h, and 6h, in particular, have a stronger antimicrobial effect than the other of the synthesized compounds. It was found that 4h showed more activity especially on E. faecalis. These results are due to the presence of nitro (NO2) group in the synthesized compound series unlike the others. In previous studies on this topic, compounds with similar structures were found to have significant antimicrobial activities67,68. In addition, compounds 4b and 6h have significant antimicrobial effects on S. aureus. In the literature, structures similar to these compounds have been shown to have significant antimicrobial effects on S. aureus69,70. S. aureus is an important bacterial pathogen in humans that can cause both community-acquired and nosocomial infections and can cause a variety of clinical manifestations including respiratory, urinary, skin, soft tissue, and bloodstream infections71,72. During the Covid 19 pandemic, some results have shown that S. aureus is associated with Covid 19 co-infection73. It is believed that the synthesized compounds can also be used for this purpose.

Time-kill kinetics assay

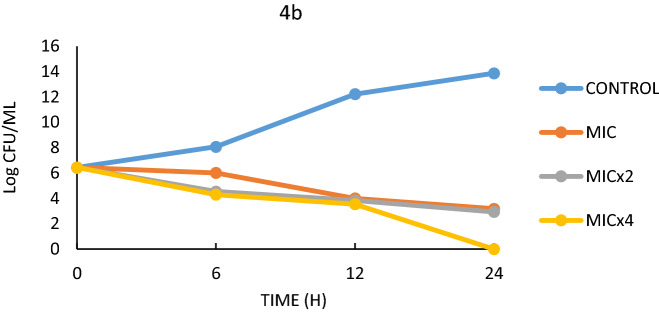

In the time-killing study, compounds 4b, 4h, and 6h were realised to have the greatest antimicrobial activity. The effects of these compounds on E. faecalis and S. aureus were studied for 24 h. Figures 3, 4, 5, 6 and Table 5 show the growth curves and t99 values of the bacteria as log cfu/mL. The t99 value is expressed as the time equivalent to 2 log drops. In other words, t99 refers to the time it takes for the bacterial count to decrease by 100 times the initial density.

Figure 3.

Effect of 4b on E. faecalis.

Figure 4.

Effect of 4h on E. faecalis.

Figure 5.

Effect of 4b on S. aureus.

Figure 6.

Effect of 6h on S. aureus.

Table 5.

t99 values of the strains in the MIC, MICx2 and MICx4 concentrations.

| Strain | Compounds | 0.h (log) | 24.h (log) | T99 (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis | Control (E. faecalis) | 7.79 | 13.66 | > 24 | |

| 4b | MIC | 7.79 | 2.95 | 10 | |

| MICx2 | 7.79 | 2.30 | 9.09 | ||

| MICx4 | 7.79 | 0.00 | 7.14 | ||

| 4h | MIC | 7.79 | 4.85 | 16.6 | |

| MICx2 | 7.79 | 3.47 | 11.1 | ||

| MICx4 | 7.79 | 0.00 | 7.14 | ||

| S. aureus | Control (S. aureus) | 6.44 | 13.87 | > 24 | |

| 4b | MIC | 6.44 | 3.18 | 10 | |

| MICx2 | 6.44 | 2.94 | 9.52 | ||

| MICx4 | 6.44 | 0.00 | 6.89 | ||

| 6h | MIC | 6.44 | 3.90 | 20 | |

| MICx2 | 6.44 | 2.30 | 11.76 | ||

| MICx4 | 6.44 | 0.00 | 6.89 | ||

Based on the MIC values of the antimicrobial results, three different MIC values (MIC, MICx2, MICx4) were determined in this study. Figures 3 and 4 show the life graph of E. faecalis. As can be seen here, it was found that the number of colonies of E. faecalis used as control group increased significantly within 24 h. In addition, it was found that when 4b was added to the medium, there was a significant decrease in the colony number of bacteria within 24 h for MIC, MICx2 and MICx4 values. When the t99 values were examined, it was found that the bacteria in the sample with MIC addition continued to live for 10 h. It was also found that the bacteria survived in the medium with MICx2 addition for 9.09 h and in the medium with MICx4 for 7.14 h. Thus, it was found that the increase in MIC values resulted in a significant decrease in bacterial longevity. Although it was observed that E.faecalis survived more than 24 h in the control sample (without 4h), the survival times were determined to be 16.6 h when 4h was added, 11.1 h when MICx2 was added, and 7.14 h when MICx4 was added. As can be seen here, increasing the MIC value has a significant effect on bacterial longevity.

Compounds 4b and 6h, which are thought to have potent antimicrobial activity on S. aureus, form another part of the time-killing study. In this study, bacteria were allowed to live in a nutrient medium for 24 h and colonies were counted at specific time periods. The colony count values were converted to t99 values, and the survival times of the bacteria were determined. In the study conducted over 24 h, it was found that the number of colonies in the S. aureus control sample increased sharply. In the other experimental groups, 4b and 6h were added to the medium as MIC, MICx2 and MICx4, respectively (Figs. 5, 6). For the effect of 4b medium, it was found that S.aureus continued to live for 10 h for MIC value, 9.52 h for MICx2 value and 6.89 h for MICx4 value (Table 5). As can be seen here, increasing the MIC value has a negative effect on the bacteria's ability to form colonies and thus on their lifespan (Fig. 5). Serious differences in the colony forming ability of S. aureus were also observed in 6 h media with different MIC values. While the bacterium survived more than 24 h in the control sample, it was found that the bacterium survived less than 24 h in the samples to which 6 h was added at MIC, MICx2 and MICx4 values (Fig. 6). The t99 values showed that the bacteria survived for 20 h at MIC value, 11.76 h at MICx2 value and 6.89 h at MICx4 value (Table 5).

In summary, it was found that the kill time values (t99 value) for 4b were effective for approximately the same time for both bacteria at all concentrations. Consequently, the kinetics of kill time and antimicrobial activity results studied at different concentrations are mutually supportive. In fact, similar results were obtained in the study with S. aureus.

Free radical scavenging activity

DPPH• (1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl) is a stable free radical that accepts an electron or a hydrogen radical to become a stable diamagnetic molecule. The scavenging effect of the synthesized compounds (4a–h and 6a–h) and standards (BHA, BHT and Trolox) on the DPPH• radical is shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of synthesized compounds.

The results indicate that the synthesized compounds have moderate to good free radical scavenging activity. Moreover, the radical scavenging activity increased with increasing concentration. Higher DPPH radical scavenging activity is associated with lower IC50 value.

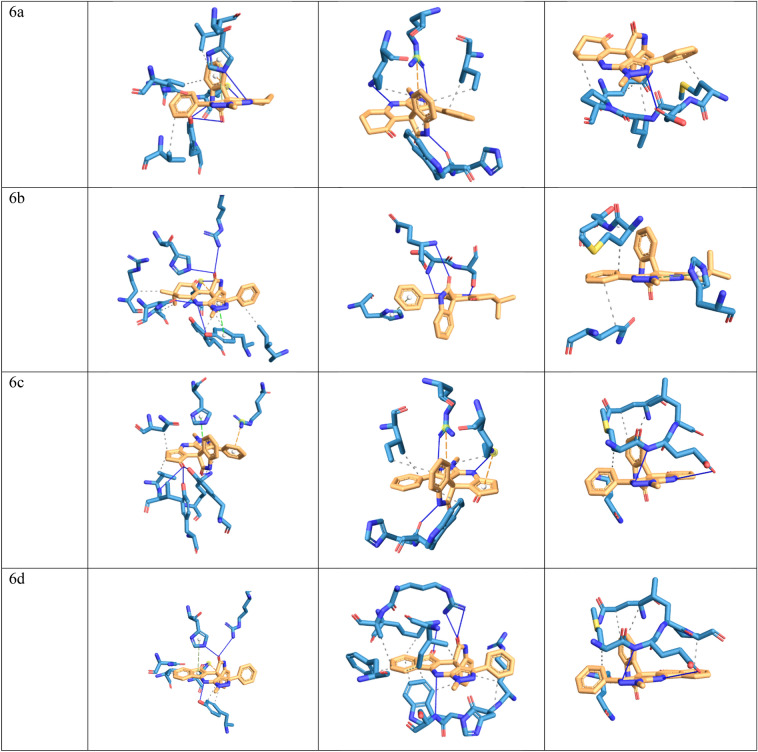

Docking study

In this study, molecular docking analysis was performed to evaluate the interaction and affinity of the synthesizing drug candidates towards three proteins: alanine racemase from E. faecalis (3E5P), biotin protein ligase from S. aureus (3V7R), COVID -19 major protease N3 complex (6LU7). Table 6, 7 and 8 show the binding energy and major residues to which the ligands bind. The compounds occupied the binding site of the target by hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bonding, pi-cation interaction and pi-stacking. The hydrogen bonds of the derivatives are retained for most of our compounds, such as LYS40 for biotin-ptorein ligase of S. aureus, ARG227 for E. faecalis, and GLU166 for Mpro-Sars-Cov2. Compounds 4d, 4f, and 6h with the highest antibacterial activities exhibited strong affinity for the target enzyme with binding energy.

Table 6.

The binding affinity of compounds 4a–h and 6a–h with E. faecalis.

| Compound | Binding energy | Hydrophobic interaction | Hydrogen bond | π-cation interaction | π-stacking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | − 8.02 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, TYR356 | LYS40, TYR44, TYR356 | ||

| 4b | − 8.48 | ASN206, VAL225, TYR356 | HIS169 | ||

| 4c | − 7.91 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, TYR356 | LYS40, TYR44, VAL225, TYR356 | LYS40,HIS169 | |

| 4d | − 7.85 | LEU86, PHE167, ASN206, VAL225, TYR356 | LYS40 | LYS40,ARG139,HIS169 | |

| 4e | − 8.02 | ASN206, TYR356 | HIS169 | LYS40 | |

| 4f | − 8.21 | ASN206, TYR356 | HIS169 | LYS40 | |

| 4g | − 8.04 | VAL38, ASN206 | LYS40, ARG139, HIS169 | LYS40,ARG139 | HIS169 |

| 4h | − 8.79 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, ARG222, TYR356 | HIS169 | LYS40 | |

| 6a | − 6.96 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, VAL225 | LYS40, TYR44, HIS169 | LYS40 | HIS169 |

| 6b | − 6.87 | VAL38, TYR44, ASN206, ARG222, ILE354, TYR356 | LYS40, ARG139, HIS169, ASN206, TYR356 | LYS40 | TYR356 |

| 6c | − 6.40 | VAL38, ASN206, TYR356 | LYS40, TYR44, VAL225, TYR356 | ARG139 | HIS169 |

| 6d | − 6.53 | VAL38, ASN206, TYR356 | LYS40, ARG139, HIS169, TYR356 | LYS40 | HIS169 |

| 6e | − 7.79 | VAL38, LYS40, LEU86, ASN206, VAL225 | LYS40, TYR44, HIS169 | HIS169 | |

| 6f | − 8.11 | LEU86, ASN206 | LYS40, TYR44, HIS169, TYR356 | HIS169 | |

| 6g | − 8.33 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, VAL225, TYR356 | LYS40, TYR44, ARG139, HIS169 | LYS40 | HIS169 |

| 6h | − 8.63 | VAL38, LEU86, ASN206, VAL225, TYR356 | LYS40, TYR44, TYR44, HIS169 | LYS40,ARG139 | HIS169 |

AlaR (PDB: 3E5P).

Table 7.

The binding affinity of compounds 4a–h and 6a–h with Staphylococcus aureus biotin protein ligase (PDB: 3V7R).

| Compound | Binding energy | Hydrophobic interaction | Hydrogen bonds | π-stacking | π-cation interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | − 7.59 | ARG125, HIS126, TRP127, ILE224 | LYS187, ARG227 | ||

| 4b | − 7.65 | ARG125, TRP127, LYS187, ILE224, ALA228 | ARG125, LYS187, ARG227 | HIS126 | |

| 4c | − 7.24 | LYS187, ARG227 | |||

| 4d | − 7.45 | ARG125, TRP127, LYS187, PHE220, ILE224, ALA228 | ARG125, ASP180, LYS187, ARG227 | HIS126 | |

| 4e | − 8.28 | ARG125, TRP127, LYS187, ILE224 | |||

| 4f | − 8.26 | ARG125, TRP127, LYS187, ILE224, ALA288 | SER128, LYS187, ARG227 | ||

| 4g | − 7.18 | ARG125, HIS126, ILE224 | ARG227 | ARG125 | |

| 4h | − 7.59 | GLU115, ASP221 | HIS126 | ||

| 6a | − 5.99 | TRP127, LYS187, ILE224 | HIS126, LYS187, ARG227 | ARG227 | |

| 6b | − 6.38 | GLN116, SER129, SER130 | HIS126 | ||

| 6c | − 7.05 | TRP127, LYS187, ILE224 | HIS126, LYS187, ARG227 | LYS187,ARG227 | |

| 6d | − 6.11 | ARG125, HIS126, TRP127, PHE220, ILE224, ALA228 | SER128, LYS187, ARG227 | ||

| 6e | − 6.73 | TRP127, LYS187, ILE224 | HIS126, ARG227 | ||

| 6f. | − 6.32 | ARG125, ILE224 | HIS126, SER223 | HIS126 | |

| 6g | − 6.17 | HIS126, TRP127, LYS187, ILE224 | HIS126, LYS187, ARG227 | LYS187,ARG227 | |

| 6h | − 8.78 | TRP127, ILE224 | SER223, ARG227 |

Table 8.

The binding affinity of compounds 4a–h and 6a–h with Mpro-Sars-Cov2 (PDB: 6LU7).

| Compound | Binding energy | Hydrophobic interaction | Hydrogen bond | π-stacking | π-cation interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | − 8.22 | ASN142, MET165, GLN189 | HIS163 | ||

| 4b | − 8.61 | ASP187,GLN189 | |||

| 4c | − 7.67 | MET165,GLN189 | HIS163,GLU166 | ||

| 4d | − 8.95 | THR25,LEU27,HIS41,MET165,GLU166,GLN189 | GLY143 | ||

| 4e | − 8.39 | HIS41, PHE140, MET165, GLU166, GLN189 | GLU166 | HIS163 | |

| 4f | − 9.04 | HIS41, PHE140, MET165, GLU166, GLN189 | GLU166 | HIS163 | |

| 4g | − 7.65 | THR25, LEU27, MET165, GLN189 | GLY143, GLU166, GLN189 | HIS41 | HIS41 |

| 4h | − 7.62 | MET165, ASP187 | HIS41 | ||

| 6a | − 7.76 | MET165, LEU167, GLN192, PRO168 | GLU166 | ||

| 6b | − 8.22 | MET165, GLU166, GLN189 | HIS41 | ||

| 6c | − 7.78 | MET165,GLN189, LEU167, GLN192 | GLU166 | ||

| 6d | − 8.81 | MET165,GLN189, LEU167, GLN192, PRO168 | GLU166 | ||

| 6e | − 7.5 | MET165, GLU166, PRO168, GLN189 | GLU166, GLU189 | ||

| 6f | − 7.63 | MET165, GLU166, PRO168, GLN189, ALA191 | |||

| 6g | − 6.13 | MET165, PRO168, GLN189 | GLU166, GLU189 | ||

| 6h | − 6.37 | ASN180, PRO184, VAL186 | PHE181, PHE185 |

Meanwhile compound 6h and 4b was docked with S.aureus protein exhibited the highest binding energy of − 8.78 and − 7.65 kcal/mol respectively. Furthermore hydrogen bond was formed with HIS169 for protein 3E5P, ARG227 for 3V7R, and GLU166 for 6LU7 as illustrated in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Docking possition of compounds 4a–h, 6a–h in the active site of 3E5P, 3V7R, 6LU7.

Moreover, compounds 4b, 4h, and 6h had the highest antimicrobial activty and also revealed good binding energies were − 8.79, − 8.63, − 8.48 kcal/mol.

Compounds 6h and 4b, which were docked to the S. aureus protein, had the highest binding energy of − 8.78 and 7.65 kcal/mol, respectively. In addition, hydrogen bonds were formed with HIS169 for protein 3E5P, ARG227 for 3V7R, and GLU166 for 6LU7, as shown in Fig. 8 Moreover, compounds 4b, 4h and 6h exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity and also showed good binding energies of − 8.79, − 8.63, − 8.48 kcal/mol, respectively.

Conclusions

In conclusion, spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]dione derivatives and spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]dione derivatives were synthesized via one-pot three-component reactions of isatins, naphthalene-1-amine or 5-amino-1-methyl-3-pheylpyrazole, and 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds in the presence of ( ±)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid in H2O/EtOH solvent under ultrasound-promoted conditions. This procedure represents a useful, simple and effective green approach to obtain spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]diones and spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]diones in high yields. The synthesized compounds showed moderate to good free radical scavenging activities.

From the present studies, isatin-based quinoline-pyrazole-indoline hybrids have shown good antimicrobial and antioxidant activities and effects on covid-19.

The antimicrobial activities of these compounds were determined. Compounds 4b, 4h and 6h showed higher activities.

Compound 4b showed promising broad spectrum antibacterial activities against S. aureus and E. faecalis, which could be attributed to the incorporated alkylated cyclohexanone moiety of spirooxindole.

On the other hand, compound 4h showed significant antibacterial activity against Enterococcus faecalis (MIC of 375 µg/mL).

Docking studies for these compounds were performed to gain insight into the mode of action, indicating that the best binding with isatin moiety was all compounds with hydrogen bonds formed by the Lys40, His169 for inhibition of 3E5P, Arg227, His126 for inhibition of 3V7R and GLU166 for inhibition of 6LU7.

Moreover, compounds 4h, 6h, and 4b had the highest antimicrobial activity and also showed good binding energies of − 8.79, − 8.63, − 8.48 kcal/mol, respectively. However, other experimental studies on covid activity may also support docking studies.

Experimental

Materials and methods

The NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III-500 MHz NMR. Chemical shifts are given in ppm downfield from Me4Si in DMSO-d6 solution. Coupling constants are given in Hz. MS spectra were performed on an AB Sciex 3200 QTRAP LC-MS/MS. The FTIR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer FT-IR spectrometer (ATR) and absorption frequencies are reported in cm−1. Elemental analyses were performed with CHNS-932 LECO apparatus and were in good agreement (± 0.2%) with the calculated values. Ultrasonication was performed in an Alex Ultrasonic Bath with a frequency of 32 kHz and a power of 230 W. Melting points were measured on a Gallenkamp melting-point apparatus. TLC was performed on standard conversion aluminum sheets pre-coated with a 0.2-mm layer of silica gel. All of the reagents were commercially available.

General procedure for the synthesis of compounds (4a–h and 6a–h) under ultrasonic irradiation

CSA (0.05 mmol) was added to a solution of 5-amino-1-methyl-3-phenylpyrazole (1.00 mmol) or 1-naphthylamine (1.00 mmol), isatin (1.00 mmol), and β-diketones (1.00 mmol) in H2O/EtOH (3/1, v/v, 8 mL) at room temperature and then the reaction mixture was sonicated at 50 °C for the time indicated in Tables 2, 3. After completion of the reaction, as indicated by TLC monitoring, the resultant solid was washed with water and ethanol and then recrystallized from ethanol to give products 4a–h and 6a–h.

10,11-dihydro-8H-spiro[benzo[c]acridine-7,3′-indoline]-2′,8(9H,12H)-dione (4a)

White powder, 0.322 g (88%). Mp: 278–281 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3362 (N–H), 3295 (N–H), 3059 (aromatic = C–H), 2939 (aliphatic C–H), 1697 (C=O), 1604, 1514 (aromatic C=C), 1499, 1469 (aliphatic C–H), 1333, 1275 (aliphatic C–C), 1086 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.85–1.96 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.12–2.21 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.79–2.88 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.39–7.79 (m, 8H, Ar H), 8.33 (d, J = 8.34, 1H, Ar H), 8.50 (d, J = 8.49 Hz, 1H, Ar–H), 9.88 (s, 1H, NH), 10.39 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 21.09 (aliphatic CH2), 27.21 (aliphatic CH2), 36.71 (aliphatic CH2), 51.65 (quarternary C), 106.95 (Ar C), 107.21(Ar C), 108.85 (Ar C), 118.52 (Ar C), 121.39 (Ar C), 121.48 (Ar C), 122.11 (Ar C), 123.08 (Ar C), 123.36 (Ar C), 124.15 (Ar C), 126.30 (Ar C), 127.29 (Ar C), 128.02 (Ar C), 129.96 (Ar C), 132.50 (Ar C), 140.33 (Ar C), 141.16 (Ar C), 154.51 (Ar C), 180.98 (C=O), 192.83 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 366, 367; Anal. Calcd for C24H18N2O2: C, 78.67; H, 4.95; N, 7.65; O, 8.73; Found: C, 78.91; H, 4.78; N, 7.86%.

10,10-dimethyl-10,11-dihydro-8H-spiro[benzo[c]acridine-7,3′-indoline]-2',8(9H,12H)-dione (4b)44

White powder, 0.330 g (84%). Mp: 284–286 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3516 (N–H), 3252 (N–H), 3008 (aromatic = C–H), 2957 (aliphatic C-H), 1739, 1721 (C=O), 1609, 1592 (aromatic C=C), 1485, 1461 (aliphatic C–H), 1333, 1266 (aliphatic C–C), 1133, 1093 (C–N) cm−1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.04 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.07 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 2.00 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, aliphatic CH2), 2.17 (br s, 1H, aliphatic CH2), 2.51 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.68 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.75–6.92 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.09 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.38 (m, 1H, Ar H), 7.53 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 8.49 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 9.35 (s, 1H, NH), 10.40 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 18.50 (aliphatic CH3), 27.01 (aliphatic CH3), 28.45(aliphatic C(CH3)2), 32.15 (aliphatic CH2), 50.31 (aliphatic CH2), 56.01 (quarternary C), 105.94 (Ar C), 108.93 (Ar C), 118.62 (Ar C), 121.39 (Ar C), 122.17 (Ar C), 123.06 (Ar C), 123.19 (Ar C), 124.14 (Ar C), 124.18 (Ar C), 126.02 (Ar C), 126.26 (Ar C), 127.27 (Ar C), 127.99 (Ar C), 130.20 (Ar C), 132.56 (Ar C), 140. 19 (Ar C), 141.26 (Ar C), 152. 56 (Ar C), 180.82 (C=O), 192.48 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 394, 395; Anal. Calcd for C26H22N2O2: C, 79.16; H, 5.62; N, 7.10; O, 8.11; Found: C, 78.98; H, 5.49; N, 7.27%.

9,10-dihydrospiro[benzo[h]cyclopenta[b]quinoline-7,3'-indoline]-2′,8(11H)-dione (4c)

White powder, 0.299 g (85%). Mp: 281–283 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3219 (N–H), 3040 (aromatic = C–H), 2955 (aliphatic C–H), 1712 (C=O), 1607, 1515 (aromatic C=C), 1463, 1381 (aliphatic C–H), 1333, 1228 (aliphatic C=C), 1093, 1064 (C-N) cm−1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 2.29–2.32 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.88–2.92 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.85–6.95 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.12–7.19 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.41–7.64 (m, 5H), 10.30 (s, 1H, NH), 10.46 (s, 1H) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 24.87 (aliphatic CH2), 33.02 (aliphatic CH2), 56.02 (quarternary C), 109.22 (Ar C), 110.44 (Ar C), 117.49 (Ar C), 118.42 (Ar C), 121.26 (Ar C), 121.96 (Ar C), 122.69 (Ar C), 123.46 (Ar C), 124.38 (Ar C), 124.84 (Ar C), 126.24 (Ar C), 126.44 (Ar C), 128.09 (Ar C), 131.79 (Ar C), 132.82 (Ar C), 138.24 (Ar C), 141.43 (Ar C), 166.13 (Ar C), 179.38 (C = O), 199.06 (C = O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 352, 353; Anal. Calcd for C23H16N2O2: C, 78.39; H, 4.58; N, 7.95; O, 9.08; Found: C, 78.53; H, 4.46; N, 8.09%.

Spiro[benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-7,3'-indoline]-2',8(13H)-dione (4d)44

Red powder, 0.356 g (89%). Mp: 297–299 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3345 (N–H), 3086 (aromatic = C–H), 2912 (aliphatic C–H), 1702 (C=O), 1621, 1590 (aromatic C=C), 1483, 1468 (aliphatic C–H), 1350, 1278 (aliphatic C–C), 1119, 1089 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 6.62–6.79 (m, 3H, Ar H), 6.90–7.12 (m, 4H, Ar H), 7.18–7.70 (m, 4H, Ar H), 7.90–8.70 (m, 3H, Ar H), 10.38 (s, 1H, NH), 10.63 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 52.41 (quarternary C), 109.52 (Ar C), 109.85 (Ar C), 120.09 (Ar C), 120.61 (Ar C), 121.49 (Ar C), 122.18 (Ar C), 123.42 (Ar C), 124.58 (Ar C), 126.51 (Ar C), 126.76 (Ar C), 128.19 (Ar C), 128.30 (Ar C), 128.79 (Ar C), 130.40 (Ar C), 131.36 (Ar C), 132.86 (Ar C), 133.74 (Ar C), 135.88 (Ar C), 136.32 (Ar C), 137.96 (Ar C), 141.41 (Ar C), 142.05 (Ar C), 142.70 (Ar C), 156.02 (Ar C), 175.68 (C = O), 189.15 (C = O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 400, 401; Anal. Calcd for C27H16N2O2: C, 80.99; H, 4.03; N, 7.00; O, 7.99; Found: C, 81.17; H, 4.18; N, 6.88%.

5′-nitro-10,11-dihydro-8H-spiro[benzo[c]acridine-7,3'-indoline]-2′,8(9H,12H)-dione (4e)

White powder, 0.349 g (85%). Mp: 287–290 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3502 (N–H), 3298 (N–H), 3076 (aromatic = C–H), 2946 (aliphatic C–H), 1707 (C=O), 1653, 1621 (aromatic C=C), 1511, 1479 (aliphatic C–H), 1331, 1280 (aliphatic C–C), 1079 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.83–1.96 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.15–2.24 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.76–2.92 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.56–7.65 (m, 7H, Ar H), 8.13–8.54 (m, 2H, Ar H), 10.33 (s, 1H, NH), 11.16 (s, 1H, NH) ppm.13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 21.45 (aliphatic CH2), 27.63 (aliphatic CH2), 36.90 (aliphatic CH2), 52.22 (quarternary C), 106.76 (Ar C), 109.63 (Ar C), 117.38 (Ar C), 119.12 (Ar C), 122.04 (Ar C), 122.67 (Ar C), 123.56 (Ar C), 124.05 (Ar C), 125.56 (Ar C), 126.83 (Ar C), 127.16 (Ar C), 128.59 (Ar C), 130.71 (Ar C), 133.19 (Ar C), 141.16 (Ar C), 142.65 (Ar C), 148.55 (Ar C), 155.92 (Ar C), 181.78 (C=O), 193.71 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 411, 412; Anal. Calcd for C24H17N3O4: C, 70.07; H, 4.16; N, 10.21; O, 15.56; Found: C, 70.23; H, 4.28; N, 10.13%.

10,10-dimethyl-5′-nitro-10,11-dihydro-8H-spiro[benzo[c]acridine-7,3′-indoline]-2′,8(9H,12H)-dione (4f)

White powder, 0.381 g (87%). Mp: 292–295 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3504 (N–H), 3319 (N–H), 3080 (aromatic = C-H), 2956 (aliphatic C-H), 1713 (C = O), 1652, 1625 (aromatic C = C), 1483, 1412 (aliphatic C-H), 1381, 1250 (aliphatic C–C), 1176, 1075 (C-N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.05 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.08 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.99–2.21 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.66–2.75 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.58–6.65 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.07–7.56 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.62–8.50 (m, 3H, Ar H), 10.70 (s, 1H, NH), 11.17 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 27.82 (aliphatic CH3), 28.45 (aliphatic CH3), 32.79 (aliphatic C(CH3)2), 50.36 (aliphatic CH2), 52.14 (CH2), 56.47 (quarternary C), 105.39 (Ar C), 109.73 (Ar C), 117.35 (Ar C), 118.85 (Ar C), 122.03 (Ar C), 122.69 (Ar C), 124.05 (Ar C), 124.21 (Ar C), 125.60 (Ar C), 126.88 (Ar C), 127.18 (Ar C),128.60 (Ar C), 130.85 (Ar C), 133.21 (Ar C), 141.03 (Ar C), 142.60 (Ar C), 148.61 (Ar C), 154.01 (Ar C), 181.69 (C = O), 193.44 (C = O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 439, 440; Anal. Calcd for C26H21N3O4: C, 71.06; H, 4.82; N, 9.56; O, 14.56; Found: C, 70.91; H, 4.94; N, 9.47%.

5′-nitro-9,10-dihydrospiro[benzo[h]cyclopenta[b]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]-2′,8(11H)-dione (4g)

White powder, 0.357 g (90%). Mp: > 300 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3208 (N–H), 3032 (aromatic C–H), 2962 (aliphatic C–H), 1718 (C=O), 1605, 1510 (aromatic C=C), 1460, 1380 (aliphatic C–H), 1330, 1226 (aliphatic C–C), 1080, 1065 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 2.26–2.30 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.79–2.97 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 6.58–6.60 (m, 1H, Ar H), 7.12–7.15 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.43–7.45(m, 2H, ArH), 7.64–7.69 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.83–8.16 (m, 3H, Ar H), 10.52 (s, 1H, NH), 11.28 (s, 1H, NH) ppm.13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 25.53 (aliphatic CH2), 33.39 (aliphatic CH2), 51.75 (quarternary C), 109.97 (Ar C), 110.16 (Ar C), 117.20 (Ar C), 120.30 (Ar C), 121.87 (Ar C), 122.62 (Ar C), 123.19 (Ar C), 124.24 (Ar C), 124.93 (Ar C), 126.07 (Ar C), 127.03 (Ar C), 128.69 (Ar C), 132.56 (Ar C), 133.45 (Ar C), 139.03 (Ar C), 142.97 (Ar C), 148.63 (Ar C), 167.24 (Ar C), 180.27 (C = O), 199.87 (C = O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 397, 398; Anal. Calcd for C23H15N3O4: C, 69.52; H, 3.80; N, 10.57; O, 16.10; Found: C, 69.68; H, 3.73; N, 10.37%.

5′-nitrospiro[benzo[h]indeno[1,2-b]quinoline-7,3'-indoline]-2′,8(13H)-dione (4h)44

Red powder, 0.409 g (92%). Mp: < 300 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3336 (N–H), 3082 (aromatic C-H), 2918 (aliphatic C-H), 1705 (C=O), 1618, 1586 (aromatic C=C), 1480, 1460 (aliphatic), 1352, 1275 (aliphatic C–C), 1117, 1080 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 6.62–6.97 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.19–7.43 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.53–7.62 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.93–8.55 (m, 4H, Ar H), 10.51 (s, 1H, NH), 11.40 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 52.11 (quaternary C, C-11), 110.44 (Ar C, C-12), 110.61 (Ar C, C-30), 118.82 (Ar C, C-7), 120.62 (Ar C, C-9), 120.77 (Ar C, C-6), 121.53 (Ar C, C-29), 122.52 (Ar C, C-21), 123.33 (Ar C, C-5), 125.04 (Ar C, C-1), 125.64 (Ar C, C-8), 126.32 (Ar C, C-2), 126.89 (Ar C, C-27), 127.54 (Ar C, C-18), 128.74 (Ar C, C-3), 129.72 (Ar C, C-19), 132.12 (Ar C, C-4), 133.54 (Ar C, C-20), 136.70 (Ar C, C-17), 136.92 (Ar C, C-23), 138.80 (Ar C, C-16), 142.08 (Ar C, C-10), 143.20 (Ar C-28), 149.94 (Ar C-24), 156.95 (Ar C, C-13), 176.93 (C=O, C-26), 180.39 (C = O, C-15) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 445, 446; Anal. Calcd for C27H15N3O4: C, 72.80; H, 3.39; N, 9.43; O, 14.37; Found: C, 72.69; H, 3.62; N, 9.30%.

1′-methyl-3′-phenyl-6′,7′,8′,9′-tetrahydrospiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]-2,5′(1′H)-dione (6a)

White powder, 0.332 g (84%). Mp: 276–279 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3356 (N–H), 3238 (N–H), 3006 (aromatic = C–H), 2937 (aliphatic C–H), 1690 (C=O), 1620, 1546 (aromatic C=C), 1493, 1466 (aliphatic C–H), 1324, 1254 (aliphatic C–C), 1135, 1086 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.81–1.93 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.06–2.17 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.69 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3.77 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.45 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.53 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 6.80 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.88 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.98–7.08 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 9.70 (s, 1H, NH), 10.04 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 21.01 (aliphatic CH2), 27.72 (aliphatic CH2), 35.06 (aliphatic CH2), 37.12 (N-CH3), 50.12 (quarternary C), 99.81 (Ar C), 108.52 (Ar C), 108.92 (Ar C), 120.90 (Ar C), 123.03 (Ar C), 127.01 (Ar C), 127.06 (Ar C), 127.28 (Ar C), 128.39 (Ar C), 129.12 (Ar C), 132.50 (Ar C), 133.39 (Ar C), 137.23 (Ar C), 138.55 (Ar C), 142.30 (Ar C), 147.02 (Ar C), 153.88 (Ar C), 179.66 (C=O), 193.12 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 396, 397; Anal. Calcd for C24H20N4O2: C, 72.71; H, 5.08; N, 14.13; O, 8.07; Found: C, 72.30; H, 5.15; N, 13.98%.

1′,7′,7′-trimethyl-3′-phenyl-6′,7′,8′,9′-tetrahydrospiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]-2,5′(1′H)-dione (6b)

Beige powder, 0.368 g (87%). Mp: 278–281 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3618 (N–H), 3320 (N–H), 3087, 3011 (aromatic = C–H), 2988, 2956 (aliphatic C–H), 1682 (C=O), 1629, 1576 (aromatic C=C), 1472, 1406 (aliphatic C–H), 1366, 1320, 1285 (aliphatic C–C), 1196, 1084 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.01 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.04 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.96 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H, aliphatic CH2), 2.08 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H, aliphatic CH2), 2.51 (dd, J1 = 3.5 Hz, J2 = 1.8 Hz, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3.78 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.47 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.54–6.57 (m, 2H, Ar H), 6.79–6.83 (m, 1H, Ar H), 6.88 (m, 1H, Ar H), 7.01–7.07 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.16–7.20 (m, 1H, Ar H), 9.72 (s, 1H, NH), 10.01 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 26.82 (aliphatic CH3), 28.13 (aliphatic CH3), 32.04 (aliphatic C(CH3)2), 35.07 (N-CH3), 41.00 (aliphatic CH2), 49.01 (aliphatic CH2), 50.56 (quarternary C), 99.81 (Ar C), 107.64 (Ar C), 108.59 (Ar C), 120.93 (Ar C), 122.91 (Ar C), 123.06 (Ar C), 127.08 (Ar C), 127.29 (Ar C), 128.37 (Ar C), 133.41 (Ar C), 137.37 (Ar C), 138.47 (Ar C), 142.35 (Ar C), 147.02 (Ar C), 151.92 (Ar C), 179.57 (C=O), 192.82 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 424, 425; Anal. Calcd for C26H24N4O2: C, 73.56; H, 5.70; N, 13.20; O, 7.54; Found: C, 73.62; H, 5.53; N, 13.43%.

1-methyl-3-phenyl-6,7-dihydro-1H-spiro[cyclopenta[e]pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4,3′-indoline]-2′,5(8H)-dione (6c)

White powder, 0.343 g (90%). Mp: > 300 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3485 (N–H), 3315 (N–H), 3119, 3007 (aromatic = C–H), 2925, 2815 (aliphatic C–H), 1666 (C=O), 1612, 1587 (aromatic C=C), 1487, 1470 (aliphatic C–H), 1357, 1290 (aliphatic C–C gerilmeleri), 1177, 1074 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 2.26 (dd, J1 = 10.8 Hz, J2 = 5.0 Hz, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.71–2.80 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3.81 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.61 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.68–6.72 (m, 2H, Ar H), 6.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.90 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.09 (td, J1 = 7.6 Hz, J2 = 1.1 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.16 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar H) 10.13 (s, 1H, NH), 10.83 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 23.95 (aliphatic CH2), 33.42 (aliphatic CH2), 35.15 (N–CH3), 47.74 (quarternary C), 99.58 (Ar C), 108.87 (Ar C), 113.10 (Ar C), 121.44 (Ar C), 123.95 (Ar C), 127.38 (Ar C), 127.70 (Ar C), 128.04 (Ar C), 131.30 (Ar C), 136.47 (Ar C), 139.77 (Ar C), 142.00 (Ar C), 147.15 (Ar C), 166.13 (Ar C), 178.34 (C=O), 198.81 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 382, 383; Anal. Calcd for C23H18N4O2: C, 72.24; H, 4.74; N, 14.65; O, 8.37; Found: C, 72.38; H, 4.53; N, 14.59%.

1-methyl-3-phenyl-1H-spiro[indeno[2,1-e]pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4,3′-indoline]-2′,5(10H)-dione (6d)

Red powder, 0.382 g (89%). Mp: > 300 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3357 (N–H), 3046, 3020 (aromatic = C–H), 2914 (aliphatic C–H), 1684 (C=O), 1664, 1620 (aromatic C=C), 1483, 1470 (aliphatic C–H), 1340, 1255 (aliphatic C–C), 1070 (C–N) cm−1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 3.96 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.67 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.78 (m, 2H, Ar H), 6.84 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.99 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.02–7.15 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.37 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.50 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.78 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 10.18 (s, 1H, NH), 11.04 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 35.81 (N–CH3), 47.46 (quarternary C), 101.05 (Ar C), 106.00 (Ar C), 109.09 (Ar C), 119.65 (Ar C), 120.22 (Ar C), 121.57 (Ar C), 123.09 (Ar C), 123.87 (Ar C), 124.05 (Ar C), 127.16 (Ar C), 127.40 (Ar C), 127.79 (Ar C), 127.94 (Ar C), 130.35 (Ar C), 131.64 (Ar C), 133.15 (Ar C), 133.89 (Ar C), 136.08 (Ar C), 136.36 (Ar C), 139.27 (Ar C), 141.95 (Ar C), 147.50 (Ar C), 155.67 (Ar C), 178.44 (C=O), 188.67 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 430, 431; Anal. Calcd for C27H18N4O2: C, 75.34; H, 4.21; N, 13.02; O, 7.43; Found: C, 75.28; H, 4.11; N, 13.26%.

1′-methyl-5-nitro-3′-phenyl-6′,7′,8′,9′-tetrahydrospiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]-2,5′(1′H)-dione (6e)

White powder, 0.379 g (86%). Mp: 283–286 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3632 (N–H), 3222 (N–H), 3004 (aromatic = C–H), 2943 (aliphatic C–H), 1704 (C=O), 1602, 1595 (aromatic C=C), 1462, 1443 (aliphatic C-H), 1360, 1251 (aliphatic C–C), 1121, 1058 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.87–1.89 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.12–2.15 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.68–2.77 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3.79 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.55 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.59 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.66 (s, 1H, Ar H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 10.27 (s, 1H, NH), 10.48 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 21.43 (aliphatic CH2), 28.14 (aliphatic CH2), 35.73 (aliphatic CH2), 37.26 (N-CH3), 49.53 (quarternary C), 99.35 (Ar C), 108.29 (Ar C), 108.86 (Ar C), 118.72 (Ar C), 125.16 (Ar C), 127.78 (Ar C), 128.09 (Ar C), 128.62 (Ar C), 128.89 (Ar C), 133.44 (Ar C), 137.71 (Ar C), 139.54 (Ar C), 142.14 (Ar C), 147.50 (Ar C), 155.50 (Ar C), 180.77 (C = O), 193.97 (C = O). MS: m/z (ESI): 441, 442; Anal. Calcd for C24H19N5O4: C, 65.30; H, 4.34; N, 15.86; O, 14.50; Found: C, 65.47; H, 4.23; N, 15.71%.

1′,7′,7′-trimethyl-5-nitro-3′-phenyl-6′,7′,8′,9′-tetrahydrospiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]-2,5′(1′H)-dione (6f)

White powder, 0.398 g (85%). Mp: 294–297 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3646 (N–H), 3318 (N–H), 3017 (aromatic = C–H), 2955 (aliphatic C–H), 1695 (C=O), 1605, 1597 (aromatic C=C), 1475, 1447 (aliphatic C–H), 1337, 1283 (aliphatic C–C), 1190, 1094 (C–N) cm−1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 1.00 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 1.02 (s, 3H, aliphatic CH3), 2.02–2.03 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.55–2.65 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3,79 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 6.56 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 6.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, Ar H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.63 (dd, J1 = 7.2 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.96–7.98 (dd, J1 = 8.5 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 10.23 (s, 1H, NH), 10.50 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 27.79 (aliphatic CH3), 28.02 (aliphatic CH3), 32.66 (aliphatic C(CH3)2), 35.73 (N-CH3), 49.42 (aliphatic CH2), 50.69 (aliphatic CH2), 56.46 (quarternary C), 99.29 (Ar C), 107.00 (Ar C), 108.92 (Ar C), 118.49 (Ar C), 125.20 (Ar C), 127.80 (Ar C), 128.10 (Ar C), 128.87 (Ar C), 130.62 (Ar C), 133.44 (Ar C), 137.84 (Ar C), 139.46 (Ar C), 142.10 (Ar C), 147.50 (Ar C), 149.36 (Ar C), 153.55 (Ar C), 180.69 (C=O), 193.68 (C=O). MS: m/z (ESI): 469, 470; Anal. Calcd for C26H23N5O4: C, 66.51; H, 4.94; N, 14.92; O, 13.63; Found: C, 66.64; H, 5.03; N, 14.98%.

1-methyl-5′-nitro-3-phenyl-6,7-dihydro-1H-spiro[cyclopenta[e]pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4,3′-indoline]-2′,5(8H)-dione (6g)

White powder, 0.388 g (91%). Mp: 277–280 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3479 (N–H), 3310 (N–H), 3075, 3025 (aromatic = C–H), 2968, 2934 (aliphatic C–H), 1701, 1667 (C=O), 1612, 1606 (aromatic C=C), 1479, 1448 (aliphatic C–H), 1329, 1297 (aliphatic C=C), 1179, 1067 (C–N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 2.25–2.27 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 2.74–2.84 (m, 2H, aliphatic CH2), 3.82 (s, 3H, N–CH3), 6.71–6.78 (m, 3H, Ar H), 7.02–7.10 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.68 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 8.02 (dd, J1 = 8.6 Hz, J2 = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 10.88 (s, 1H, NH), 11.03 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 24.66 (aliphatic CH2), 33.81 (aliphatic CH2), 35.77 (N-CH3), 48.08 (quarternary C), 99.06 (Ar C), 109.40 (Ar C), 112.29 (Ar C), 119.78 (Ar C), 123.42 (Ar C), 125.75 (Ar C), 128.06 (Ar C), 128.21 (Ar C), 128.74 (Ar C), 133.43 (Ar C), 137.37 (Ar C), 140.35 (Ar C), 142.50 (Ar C), 143.81 (Ar C), 147.66 (Ar C), 148.99 (Ar C), 167.41 (Ar C), 179.53 (C = O), 199.49 (C = O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 427, 428; Anal. Calcd for C23H17N5O4: C, 64.63; H, 4.01; N, 16.39; O, 14.97; Found: C, 64.52; H, 4.18; N, 16.45%.

1-methyl-5′-nitro-3-phenyl-1H-spiro[indeno[2,1-e]pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4,3′-indoline]-2′,5(10H)-dione (6h)

Red powder, 0.441 g (93%). Mp: > 300 °C. FTIR (ATR): v = 3207, 3161 (N–H), 3032, 3013 (aromatic = C–H), 2942 (aliphatic C–H), 1737, 1695 (C=O), 1659, 1622 (aromatic C=C), 1494, 1448 (aliphatic C–H), 1338, 1231 (aliphatic C–C), 1159, 1073 (C-N) cm-1. 1H NMR (d6-DMSO, 500 MHz): δ = 3.97 (s, 3H, N-CH3), 6.76–6.80 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.09 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.19 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, Ar H),7.52 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, Ar H), 7.81–7.85 (m, 2H, Ar H), 7.93–8.05 (m, 2H, Ar H), 11.00 (s, 1H, NH), 11.36 (s, 1H, NH) ppm. 13C NMR (d6-DMSO, 126 MHz): δ = 36.45 (N–CH3), 47.68 (quarternary C), 100.57 (Ar C), 104.81 (Ar C), 109.64 (Ar C), 120.13 (Ar C), 120.65 (Ar C), 120.93 (Ar C), 123.33 (Ar C), 125.94 (Ar C), 128.13 (Ar C), 129.75 (Ar C), 131.14 (Ar C), 132.38 (Ar C), 133.20 (Ar C), 136.40 (Ar C), 136.89 (Ar C), 137.28 (Ar C), 139.88 (Ar C), 142.07 (Ar C), 142.71 (Ar C), 147.92 (Ar C), 148.81 (Ar C), 149.95 (Ar C), 156.88 (Ar C), 179.66 (C=O), 189.18 (C=O) ppm. MS: m/z (ESI): 475, 476; Anal. Calcd for C27H17N5O4: C, 68.21; H, 3.60; N, 14.73; O, 13.46; Found: C, 68.28; H, 3.66; N, 14.62%.

Microdilution method

The antimicrobial study was carried out using the microdilution (MIC) method74,75. In this study, besides using Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25,923 (S.aureus) and Enterococcus faecalis (E.faecalis) as bacteria, Candida albicans ATCC 10,231 (C.albicans) was used as yeast. The stock solutions of the complexes were prepared in DMSO and used in all stages of the study. Microorganisms were grown in 5 ml of Nutrient Broth (NB) at 37 °C for 18 h in a shaker incubator. It was taken from the grown bacteria and yeast cells and added to 50 ml of NB. Afterword 106 bacteria per ml were obtained in accordance with the 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard. Followed by serial dilution and the serial dilution tubes are incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The last tube without bacterial growth is accepted as the MIC values. The MIC values were given in μg/ml. Gentamicin and flucanazole were used as control group.

Time-kill kinetics assay

After the bacteria were grown in broth (NB) at 37 °C for overnight, they were added to the other sterile broth medium at a rate of approximately 105 microorganisms per ml. MIC, MICx2, MICx4 were added to the media prepared separately from the compounds with previously determined MIC values. Colony counts were made on Nutrient Broth medium by taking samples at regular intervals for 24 h from the samples placed in the incubator at 37 °C.

The colony counts were converted into logarithmic values and presented in graphs and Table 5. In addition, the t99 values as obtained from the colony counts were defined and the life span of the bacteria was determined. The value t99 is calculated as the time corresponding to 2 logarithmic reductions during the 24-h period76. Compounds 4b, 4h and 6h which were the most effective ones compared to the MIC values were used in the study.

Free radical scavenging activity

The free radical scavenging activity was determined by the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH•). The activity was measured by following the methodology described by Brand-Williams et al.77. Briefly, 20 mg/L DPPH• in methanol was prepared and 1.5 mL of this solution was added to 0.75 mL of synthesized compounds solution in methanol at different concentrations (10–400 μg/mL). After 30 min the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Methanol (0.75 mL) in place of the sample was used as control. Lower absorbance of the reaction mixture indicates higher free radical scavenging activity. The percent inhibition activity was calculated using the following equation:

(A0 = the control absorbance and A1 = the sample solution absorbance).

Molecular docking

3V7R and 3E5P were selected as potential target proteins for the antimicrobial activity, and 6LU7 protein for the Sar-Cov-2 main protease inhibition. Known information on the PDB: 3V7R protein shows that the binding strategy of the biotin ligase enzyme of the Staphylococcus aureus protein could be selectively inhibited78. The 3E5P as a member of the Alanine racemase (AlaR) is a ubiquitous bacterial enzyme and provides the conversion between L- and D-alanine as the essential cell wall precursor79. N3 can specifically, selectivity inhibits Mpro from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV and has exhibited potent antiviral activity against infectious bronchitis virus80.

The crystalline structures of the 32G ((3aS,4S,6aR)-4-(5-{1-[4-(6-amino-9H-purin-9-yl)butyl]-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl}pentyl) complex were downloaded from the PDB IDs 3V7R protein database81. 3D crystal structure of the PRD_002214 (N-[(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)carbonyl]alanyl-l-valyl-n ~ 1 ~ -((1r,2z)-4-(benzyloxy)-4-oxo-1-{[(3r)-2-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl]methyl}but-2-enyl)-l-leucinamide) with SARS-CoV-2 (PDB ID: 6LU7) complex were downloaded from research collaboratory for structural bioinformatics protein data bank (RCSB PDB).

Firstly, each related proteins have been identified as the receptors, the complexed ligands, water as a non-amino acid residues were manually removed from the target proteins using the Discovery Studio Client (Dassault Systems BIOVIA2021), and added hydrogen atoms82.

The molecular structure of each compound was drawn accurately using ChemDraw Ultra 12.0, then optimized with the Gaussian G09 program based on density functional level of theory at Becke’s three-parameter Lee–Yang–Parr hybrid functional as B3LYP/6.311 G(d.p) basic set in a vacuum83,84. Through this process was reached the lowest energy or optimized structure of the molecule.

As part of this work, all docking studies were performed using the Autodock 485 with the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and ten different runs configured to finish after a maximum of 250,000 number of energy assessments were used to obtain the results of the docking experiment.

For the docking validation, simulation of ligand–protein interactions was carried out within Lamarckian genetic algorithms methods and the grid box was set at 40 × 40 × 40 Å in the x, y, z directions with a spacing of 0.375 Å in the active site centre. Each co-crystallized ligand was previously removed from each protein binding site. We compared the predicted docking pose with the experimental co-crystallized binding pose. The small RMSD variation (1.84 Å) was obtained from the re-docking calculations of 6LU7 native ligand, suggesting that the program could correctly and efficiently simulate the experimental results for the respective ligands. The 3V7R receptor crystal with the specified ligands as 32G 3D-crystal was simulated re-docking and the RMSD value was obtained 0.72 Å under this condition. In order to validate the docking approach for the 3E5P protein structure used, the respective co-crystallized ligand, named DCS, was docked to the protein’s active site and docking validation results of the root mean square deviation was obtained 0.82 Å (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Validation of the 3V7R and 3E5P proteins, red is native ligand conformation before docking process and blue is native ligand conformation after docking process.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Kirklareli University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit with the project number KLUBAP 168.

Author contributions

E.P. and M.G. designed the study; E.P. and G.T. performed synthesis of the samples and free radical scavenging activity studies; E.T.C. and O.I. performed antimicrobial activity studies; M.G. performed molecular docking studies; E.P., M.G. and O.I. writing-review and editing the manuscript; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-27777-z.

References

- 1.Zhu J, Wang Q, Wang M. Multicomponent Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; 2015. p. 521. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameta K, Dandia A. Multicomponent Reactions: Synthesis of Bioactive Heterocycles. CRC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trost BM. The atom economy—A search for synthetic efficiency. Science. 1991;254(5037):1471–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1962206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liou YC, Lin YA, Wang K, Yang JC, Jang YJ, Lin W, Wu YC. Synthesis of novel Spiro-tetrahydroquinoline derivatives and evaluation of their pharmacological effects on wound healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22(12):6251. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Ritika A brief review of the biological potential of indole derivatives. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;6:121. doi: 10.1186/s43094-020-00141-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salem MA, Ragab A, Askar AA, El-Khalafawy A, Makhlouf AH. One-pot synthesis and molecular docking of some new spiropyranindol-2-one derivatives as immunomodulatory agents and in vitro antimicrobial potential with DNA gyrase inhibitor. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;188:1119772. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ammar YA, AbdEl-Hafez SMA, Hessein SA, Ali AM, Askar AA, Ragab A. One-pot strategy for thiazole tethered 7-ethoxy quinoline hybrids: Synthesis and potential antimicrobial agents as dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitors with molecular docking study. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1242:130748. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubica K, Taciak P, Czajkowska A, Ignasiak AS, Wyrebiak R, Podsadni P, Bia£y IM, Malejczyk J, Mazurek AP. Synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation of some new derivatives of 2-(4-benzoyl-1-piperazinyl)-quinoline and 2-(4-cinnamoyl-1-piperazinyl)-quinoline. Acta Pol. Pharm. Drug Res. 2018;75:891–901. doi: 10.32383/appdr/80098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benard C, Zouhiri F, Normand-Bayle M, Danet M, Desmaele D, Leh H, Mauscadet JF, Mbemba G, Thomas CM, Bonnenfant S, Le Bret M, d’Angela J. Linker-modified quinoline derivatives targeting HIV-1 integrase: Synthesis and biological activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:2473–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu H-G, Li Z-W, Hu X-X, Si S-Y, You X-F, Tang S, Wang Y-X, Song D-Q. Synthesis and biological evaluation of quinoline derivatives as a novel class of broad-spectrum antibacterial agents. Molecules. 2019;24(3):548. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma S, Pandey S, Agarwal P, Verma P, Deshpande S, Saxena JK, Srivastava K, Chauhan PMS, Prabhakar YS. N-(7-chloroquinolinyl-4-aminoalkyl)arylsulfonamides as antimalarial agents: rationale for the activity with reference to inhibition of hemozoin formation. RSC Adv. 2016;6(30):25584–25593. doi: 10.1039/C6RA00846A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng C-H, Tung C-W, Wu C-H, Tzeng C-C, Chen Y-H, Hwang T-L, Chen Y-L. Discovery of indeno[1,2-c]quinoline derivatives as potent dual antituberculosis and anti-inflammatory agents. Molecules. 2017;22(6):1001. doi: 10.3390/molecules22061001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaur H, Singh J, Narasimhan B. Indole hybridized diazenyl derivatives: Synthesis, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity evaluation and docking studies. BMC Chem. 2019;13(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s13065-019-0580-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Z, Zhao Z, Huang M, Fu X. Ultrasound-assisted, one-pot, three-component synthesis and antibacterial activities of novel indole derivatives containing 1,3,4-oxadiazole and 1,2,4-triazole moieties. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2015;18:1320–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2015.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugwu DI, Okoro UC, Ukoha PO, Gupta A, Okafor SN. Novel anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents: Synthesis, molecular docking and in vivo studies. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018;33(1):405–415. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1426573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ustundag CG, Gursoy E, Naesens L, Guzeldemirci NU, Çapan G. Synthesis and antiviral properties of novel indole-based thiosemicarbazides and 4-thiazolidinones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016;24:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YY, Wu HS, Tang L, Feng CR, Yu JH, Li Y, Yang YS, Yang B, He QJ. The potential insulin sensitizing and glucose lowering effects of a novel indole derivative in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol. Res. 2007;56(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Queiroz MJRP, Abreu AS, Carvalho MSD, Ferreira PMT, Nazareth N, Sao-Jose Nascimento M. Synthesis of new heteroaryl and heteroannulated indoles from dehydrophenylalanines: Antitumor evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16(10):5584–5589. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yousif MNM, Hussein HAR, Yousif NM, El-Manawaty MA, El-Sayed WA. Synthesis and anticancer activity of novel 2-phenylindole linked imidazolothiazole, thiazolo-s-triazine and imidazolyl-sugar systems. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2019;9(1):6–14. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2019.90102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parthasarathy K, Praveen C, Jeyaveeran JC, Prince AAM. Gold catalyzed double condensation reaction: Synthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxicity of spirooxindole derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26(17):4310–4317. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumari G, Manoj Modi N, Gupta SK, Singh RK. Rhodium(II) acetate-catalyzed stereoselective synthesis, SAR and anti-HIV activity of novel oxindoles bearing cyclopropane ring. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46(4):1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Kalyoubi SA, Ragab A, Abu Ali OA, Ammar YA, Seadawy MG, Ahmed A, Fayed EA. One-pot synthesis and molecular modeling studies of new bioactive spiro-oxindoles based on uracil derivatives as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors targeting RNA polymerase and spike glycoprotein. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:376. doi: 10.3390/ph15030376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldeeb M, Sanad EF, Ragab A, Ammar YA, Mahmoud K, Ali MM, Hamdy NM. Anticancer effects with molecular docking confirmation of newly synthesized isatin sulfonamide molecular hybrid derivatives against hepatic cancer cell lines. Biomedicines. 2022;10:722. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10030722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendre DB, Toche RB, Jachak MN. Synthesis of novel dipyrazolo[3,4-b:3,4-d]pyridines and study of their fluorescence behavior. Tetrahedron. 2007;63(45):11000–11004. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.08.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schönhaber J, Müller TJJ. Luminescent bichromophoric spiroindolones—Synthesis and electronic properties. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9(18):6196–6199. doi: 10.1039/C1OB05703K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Gupta S, Rani V, Sharma P. Pyrazole containing anti-HIV agents: An update. Med. Chem. 2022;18(8):831–846. doi: 10.2174/1573406418666220106163846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding K, Lu Y, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Qiu S, Ding Y, Gao W, Stuckey J, Krajewski K, Roller PP, Tomita Y, Parrish DA, Deschamps JR, Wang S. Structure-based design of potent non-peptide MDM2 inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(29):10130–10131. doi: 10.1021/ja051147z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagender P, Naresh Kumar R, Malla Reddy G, Krishna Swaroop D, Poornachandra Y, Ganesh Kumar C, Narsaiah B. Synthesis of novel hydrazone and azole functionalized pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine derivatives as promising anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:4427–4432. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quiroga J, Villarreal Y, Galvez J, Ortiz A, Insuasty B, Abonia R, Raimondi M, Zacchino S. Synthesis and antifungal in vitro evaluation of pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridines derivatives obtained by Aza-Diels–Alder reaction and microwave irradiation. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2017;65:143–150. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c16-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salem MS, Ali MA. Novel pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine derivatives: Synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial and antiproliferative profile. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016;39(4):473–483. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayman R, Radwan AM, Elmetwally AM, Ammar YA, Ragab A. Discovery of novel pyrazole and pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine derivatives as cyclooxygenase inhibitors (COX-1 and COX-2) using molecular modeling simulation. Arch. Pharm. 2022 doi: 10.1002/ardp.202200395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alzahrani AY, Ammar YA, Salem MA, Abu-Elghait M, Ragab A. Design, synthesis, molecular modeling, and antimicrobial potential of novel 3-[(1H-pyrazol-3-yl)imino]indolin-2-one derivatives as DNA gyrase inhibitors. Arch. Pharm. 2022;355:e2100266. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202100266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Chen H, Shi C, Shi D, Ji S. Efficient one-pot synthesis of spirooxindole derivatives catalyzed by L-proline in aqueous medium. J. Comb. Chem. 2010;12(2):231–237. doi: 10.1021/cc9001185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakibaei GI, Feiz A, Bazgir A. A simple and catalyst-free three-component method for the synthesis of spiro[indenopyrazolopyridine indoline]diones and spiro[indenopyridopyrimidine indoline]triones. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2011;14(6):556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2010.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balamurugan K, Perumal S, Menendez JC. New four-component reactions in water: A convergent approach to the metal-free synthesis of spiro[indoline/acenaphthylene-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine derivatives. Tetrahedron. 2011;67(18):3201–3208. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Gao L, Xu Z, Ling Z, Qin Y, Rong L, Tu SJ. Green synthesis of novel spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine]-2,3′(7′H)-dione, spiro[indeno[1,2-b]pyrazolo[4,3-e]pyridine-4,3′-indoline]-2′,3-dione, and spiro[benzo[h]pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline-7,3′-indoline]-2′,8(5H)-dione derivatives in aqueous medium. Tetrahedron. 2017;73(4):385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2016.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danel A, Wojtasik K, Szlachcic P, Gryl M, Stadnicka K. A new regiospecific synthesis method of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoxalines—Potential materials for organic optoelectronic devices, and a revision of an old scheme. Tetrahedron. 2017;73:5072–5081. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2017.06.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meena K, Kumari S, Khurana JM, Malik A, Sharma C, Panwar H. One pot three component synthesis of spiro[indolo-3,10′-indeno[1,2-b]quinolin]-2,4,11′-triones as a new class of antifungal and antimicrobial agents. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017;28:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2016.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mondal A, Mukhopadhyay C. FeCl3-catalyzed combinatorial synthesis of functionalized spiro[indolo-3,10′-indeno [1,2-b]quinolin]-trione derivatives. ACS Comb. Sci. 2015;17(7):404–408. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.5b00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelit E. Synthesis of isoxazolopyridines and spirooxindoles under ultrasonic irradiation and evaluation of their antioxidant activity. J. Chem. 2017;9161505:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/9161505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Banna MG, El-Hashash MA, Elnaggar AM, El-Badawy AA, Rizk SA. An efficient ultrasonic synthetic approach, DFT study, and molecular docking of 6a-hydroxy-9-nitro-6,6a-dihydro-isoindolo[2,1-a]quinazoline-5,11-dione derivatives as algaecides for refining wastewater. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2021;58(7):1502–1514. doi: 10.1002/jhet.4276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attia SK, Elgendy AT, Rizk SA. Efficient green synthesis of antioxidant azacoumarin dye bearing spiro-pyrrolidine for enhancing electro-optical properties of perovskite solar cells. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1184:583–592. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.02.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rizk SA, Abdelwahab SS, Sallam AH. Regioselective reactions, spectroscopic characterization, and cytotoxic evaluation of spiro-pyrrolidine thiophene. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018;55(7):1604–1614. doi: 10.1002/jhet.3195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahmati A, Vashareh ME. Synthesis of spiro[benzo[h]quinoline-7,3-indolines] via a three-component condensation reaction. J. Chem. Sci. 2014;126:169–176. doi: 10.1007/s12039-013-0552-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quiroga J, Portillo S, Perez A, Galvez J, Abonia R, Insuasty B. An efficient synthesis of pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridine-4-spiroindolinones by a three-component reaction of 5-aminopyrazoles, isatin, and cyclic β-diketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52(21):2664–2666. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.03.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen H, Shi D. Efficient one-pot synthesis of novel spirooxindole derivatives via three-component reaction in aqueous medium. J. Comb. Chem. 2010;12(4):571–576. doi: 10.1021/cc100056p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dabiri M, Tisseh ZN, Nobahar M, Bazgir A. Organic reaction in water: A highly efficient and environmentally friendly synthesis of spiro compounds catalyzed by L-proline. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2011;94:824–830. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201000307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumari S, Sindhu J, Khurana JM. Efficient green approach for the synthesis of spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]quinoline]diones using [NMP]H2PO4 and solvatochromic and pH studies. Synth. Commun. 2015;45(9):1101–1113. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang WH, Chen MN, Hao Y, Jiang X, Zhou XL, Zhang ZH. Choline chloride and lactic acid: A natural deep eutectic solvent for one-pot rapid construction of spiro[indoline-3,4′-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridines] J. Mol. Liq. 2019;278:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.01.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang YR, Hu YJ, Zhou XH, Wu Q, Lin XF. One-pot construction of spirooxindole backbone via biocatalytic domino reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:2923–2926. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.06.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu C, Liu J, Kui D, Lemao Y, Yingjie X, Luo X, Meiyang X, Shen R. Efficient multicomponent synthesis of spirooxindole derivatives catalyzed by copper triflate. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022;42:277–289. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2020.1726976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mason TJ. Sonochemistry and the environment—Providing a ‘green’ link between chemistry, physics and engineering. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pelit E, Turgut Z. Three-component aza-Diels-Alder reactions using Yb(OTf)3 catalyst under conventional/ultrasonic techniques. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelit E. CSA catalyzed multi-component synthesis of polycyclic pyrazolo[4,3-e]pyridines under ultrasonic irradiation and their antioxidant activity. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. A. 2017;4:631–648. doi: 10.18596/jotcsa.295465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelit E, Turgut Z. Synthesis of enantiopure aminonaphthol derivatives under conventional/ultrasonic technique and their ring-closure reaction. Arab. J. Chem. 2016;9:421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelit E, Turgut Z. (+)-CSA catalyzed multicomponent synthesis of 1-[(1, 3-Thiazol-2-ylamino) methyl]-2-naphthols and their ring-closure reaction under ultrasonic irradiation. J. Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9315614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Srivastava A, Singh S, Samanta S. (±)-CSA catalyzed Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with 3-ethoxycarbonyl-3- hydoxyisoindolin-1-one: An easy access of 3-ethoxycarbonyl-3-indolylisoindolin-1-ones bearing a quaternary α-amino acid moiety. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:1444–2144. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang X, Song Z, Xu C, Yao Q, Zhang A. (D, L)- 10-camphorsulfonic-acid-catalysed synthesis of diaryl-fused 2,8-dioxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanes from 2-hydroxychalcones and naphthol derivatives. Eur. J. Organ. Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201301295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Srivastava, A., Mobin, S.M. & Samata, S. (±)CSA catalyzed one-pot synthesis of 6,7-dihydrospiro[indole-3,1-isoindoline]- 2,3,4[1H,5H)-trione derivatives: Easy access of spirooxindoles and ibophyllidien-like alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett.55, 1863–1867. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.01.154 (2014).

- 60.Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53(6):1841–1856. doi: 10.1021/jf030723c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang S, Hua M, Liu X, Du C, Pu L, Xiang P, Wang L, Liu J. Bacterial and fungal co-infections among COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit. Microbes Infect. 2021;23(4–5):104806. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2021.104806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Li X, Zhang L, Peng C, Duan Y, Yu J, Wang L, Yang K, Liu F, Jiang R, Yang X, You T, Liu X, Yang X, Bai F, Liu H, Liu X, Guddat LW, Xu W, Xiao G, Qin C, Shi Z, Jiang H, Rao Z, Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soares da Costa TP, Tieu W, Yap MY, Pendini NR, Polyak SW, Sejer Pedersen D, Morona R, Turnidge JD, Wallace JC, Wilce MCJ, Booker GW, Abell AD. Selective inhibition of biotin protein ligase from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(21):17823–17832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Priyadarshi A, Lee EH, Sung MW, Nam KH, Lee WH, Kim EE, Hwang KY. Structural insights into the alanine racemase from Enterococcus faecalis. Biochim. Biophys. (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2009;1794(7):1030–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamer O, Avcı D, Çelikoğlu E, Idil O, Atalay Y. Crystal growth, structural and spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial activity, DNA cleavage, molecular docking and density functional theory calculations of Zn(II) complex with 2-pyridinecarboxylic acid. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018;32:e4540. doi: 10.1002/aoc.4540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tamer Ö, Avcı D, Çelikoğlu E, İdil Ö, Atalay Y. Crystal growth, structural and spectroscopic characterization, antimicrobial activity, DNA cleavage, molecular docking and density functional theory calculations of Zn (II) complex with 2-pyridinecarboxylic acid. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018;32(11):e4540. doi: 10.1002/aoc.4540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buyukkidan N, Yenikaya C, Ilkimen H, Karahan C, Darcan C, Korkmaz T, Suzen Y. Synthesis, characterization and biological activities of metal (II) dipicolinate complexes derived from pyridine-2, 6-dicarboxylic acid and 2-(piperazin-1-yl) ethanol. J. Mol. Struct. 2015;1101:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asiri YI, Muhsinah AB, Alsayari A, Venkatesan K, Al-Ghorbani M, Mabkhot MN. Design, synthesis and antimicrobial activity of novel 2-aminothiophene containing cyclic and heterocyclic moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021;44:128117. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shinde RA, Adole VA, Jagdale BS, Pawar TB. Superfast synthesis, antibacterial and antifungal studies of halo-aryl and heterocyclic tagged 2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one candidates. Monatsh. für Chem.—Chem. Mon. 2021;152:649–658. doi: 10.1007/s00706-021-02772-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O’Donnell F, Smyth TJP, Ramachandran VN, Smyth WF. A study of the antimicrobial activity of selected synthetic and naturally occurring quinolines. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;35:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG. Staphylococcus aureus infections: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sanlı K. Hastane kokenli ve toplum kaynaklı Staphylococcus aureus suslarının cesitli antimikrobiyallere duyarlılıkları. IKSSTD. 2020;12(2):188–193. doi: 10.5222/iksstd.2020.64326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adeiza SS, Shuaibu AB, Shuaibu GM. Random effects meta-analysis of COVID-19/S. aureus partnership in co-infection. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control. 2020;15:Doc29. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdel-Rahman LH, Abu-Dief AM, Basha M, Abdel-Mawgoud AAH. Three novel Ni(II), VO(II) and Cr(III) mononuclear complexes encompassing potentially tridentate imine ligand: Synthesis, structural characterization, DNA interaction, antimicrobial evaluation and anticancer activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2017;31:e3750. doi: 10.1002/aoc.3750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Abu-Dief AM, El-Metwaly NM, Alzahrani SO, Bawazeer AM, Shaaban S, Adam MSS. Targeting ctDNA binding and elaborated in-vitro assessments concerning novel Schiff base complexes: Synthesis, characterization, DFT and detailed in-silico confirmation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;322:114977. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hatha, A. A. M., Chandran, A., Asit, M., Sherin, V., Thomas, A. P. Influence of a salt water regulator on the survival response of Salmonella Paratyphi in Vembanadu Lake: India (2013).

- 77.Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995;28:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Da Costa TPS, Tieu W, Yap MY, Pendini NR, Polyak SW, Pedersen DS, Abell AD. Selective inhibition of biotin protein ligase from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287(21):17823–17832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Priyadarshi A, Lee EH, Sung MW, Nam KH, Lee WH, Kim EE, Hwang KY. Structural insights into the alanine racemase from Enterococcus faecalis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2009;1794(7):1030–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jin Z, Du X, Xu Y, Deng Y, Liu M, Zhao Y, Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berman HM, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.https://3ds.com/products-services/biovia/products.

- 83.Becke A. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37(2):785. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and supplementary materials.