Abstract

Heat-not-burn products, eg, I quit ordinary smoking (IQOS), are becoming popular alternative tobacco products. The nicotine aerosol protonation state has addiction implications due to differences in absorption kinetics and harshness. Nicotine free-base fraction (αfb) ranges from 0 to 1. Herein, we report αfb for IQOS aerosols by exchange-averaged 1H NMR chemical shifts of the nicotine methyl protons in bulk aerosol and verified by headspace-solid phase micro-extraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The αfb ≈ 0 for products tested; likely a result of proton transfer from acetic acid and/or other additives in the largely aqueous aerosol. Others reported higher αfb for these products, however, their methods were subject to error due to solvent perturbation.

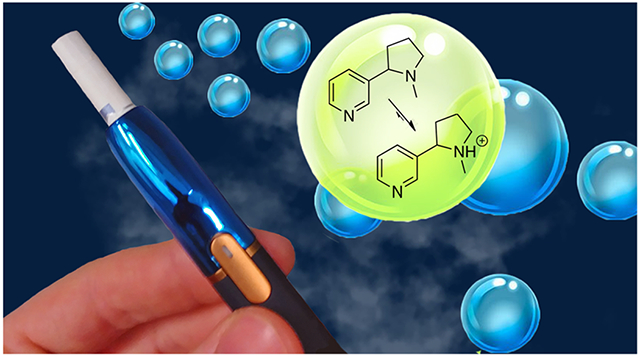

Graphical Abstract

Heat-not-burn (HNB) tobacco products, which originally received poor commercial reception when first introduced in 19881, are experiencing a rapid rise in popularity.2 As of 2017 in Japan, 4.7% of the population ages 15–69 in a cross-sectional survey panel used HNB products, and 3.6% used Phillip Morris International’s HNB product “I quit ordinary smoking” (IQOS).3 IQOS devices consist of three main components: a tobacco “heatstick,” a holder, and a charger. The heatstick, which resembles a normal cigarette, contains a “tobacco plug” of ~320 mg of reconstituted tobacco4 treated with glycerin humectant.4–6 The heatstick has two separate filter components: a polymer film and a cellulose acetate mouthpiece similar to traditional cigarettes.4,5 The heatstick inserts into the holder, which contains a small blade or flange which provides heating.4,5 In an attempt to limit formation of pyrolytic products, the IQOS operating temperature does not exceed 350 °C, which is significantly lower than the 600–900 °C combustion temperature in traditional cigarettes.4 Heating tobacco at this temperature creates an aqueous aerosol with a water content of ~57% by mass of the particulate matter (PM),7 which inspired Gasparyan et al. to dub this unique aerosol a “distillate.”7

The protonation state of nicotine in an aerosol depends on pH of the medium8,9 and has important toxicological implications, which will be briefly described.10 Of the three protonation states of nicotine (free-base [Nic], monoprotonated [NicH+], and diprotonated [NicH22+]), only Nic and NicH+ exist in significant amounts in tobacco smoke PM, because conditions therein are not sufficiently acidic to generate significant NicH22+. In order to compare relative amounts of Nic to NicH+ in an aerosol PM, free-base fraction (αfb) can thus be calculated:

| (1) |

with values ranging from 0 to 1.9–11 Nic can exist in both PM and gas phase, while NicH+ is nonvolatile and exists exclusively in PM. Nicotine phase differences may affect respiratory tract deposition as well as nicotine absorption kinetics.10 A tobacco product with greater αfb could result in a faster physiological response if this leads to a greater spike in blood nicotine concentration, implying that αfb could have implications for addiction potential.11–13 Furthermore, nociception in the posterior pharynx triggered by Nic upon inhalation14 leads to a perception of harshness, whereas a lower αfb value may be linked with a less harsh sensation upon inhalation.15,16

The αfb values for IQOS products were reported by Salman et al.,17 who used aqueous solvent extraction to quantify free-base nicotine of total PM captured on filter pads. As described by Duell et al.,11 issues related to solvent extraction can lead to significant perturbation of αfb. The novel method used herein to directly measure αfb of aerosols from IQOS products is based on one previously used by us,9,11,18 which is the only method described in the literature that uses NMR to measure αfb of e-cigarette e-liquids without perturbing the sample with a solvent.11 Results herein were cross-validated with a novel headspace-solid phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GCMS) method from Luo, Motti, McWhirter, Pankow (2019, in preparation; see SI). Total nicotine delivery was quantified by HPLC-UV based on previous methods.19–21

Previously, αfb determination by NMR was done using a concentric NMR tube insert containing pure e-cigarette e-liquid,11 condensed aerosol, or cigarette smoke,18 which was inturn surrounded by lock solvent, DMSO-d6. Duell et al. calculated αfb by comparing relative chemical shift differences between methyl and aromatic protons of Nic and NicH+ standards in glycerol/propylene glycol with commercial e-liquids.11 However, Δδ values calculated for IQOS bulk aerosol using this method resulted in inaccurate values due to inconsistencies in δ for nicotine aromatic protons, which might arise from formation of complexes between acetic acid and nicotine’s pyridine nitrogen.23 Therefore, calculation of αfb for IQOS products required use of the absolute chemical shift of nicotine methyl protons, referenced relative to 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid using eq 2:9

Puff topography was studied to assess its influence on αfb. The Health Canada Intense (HCI) puffing regime (55 mL puff volume, 2 s puff period, 30 s puff interval, with bell-shaped puffs) has been suggested as the most appropriate for these products,24 however, a variety of puffing parameters have been used in literature.25,26 Given this disagreement, two puffing parameters were used: a modified HCI (mHCI; HCI with a square-shaped puff) and that specified for e-cigarettes by the Cooperation Center for Scientific Research Relative to Tobacco (CORESTA, 55 mL puff volume, 3 s puff period, 30 s puff interval, with square-shaped puffs).27

The αfb values determined by NMR and nicotine delivery by HPLC-UV for three IQOS brands under mHCI and CORESTA are reported in Table 1. A larger assortment of HNB product αfb values are shown in Table 2. The αfb and nicotine aerosol concentration values were found to be consistent across all heatsticks tested. The αfb values consistently suggested that the majority of aerosol nicotine from these products is NicH+, with very little Nic. The αfb values determined by NMR were cross-validated using the HS-SPME-GCMS method, which found no significant difference between them for the brand tested. The puffing parameter did not significantly affect αfb or nicotine delivery. A comprehensive description of error analysis and statistical tests is presented in the SI.

Table 1.

αfb Determined by 1H NMR and Nicotine Delivery for Three Brands of IQOS Heatsticks Under mHCI and CORESTA Puffing Topographiesa

| brand/flavor | αfb mHCI | αfb CORESTA | Nic, mg, mHCI | Nic, mg, CORESTA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parliament | 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 1.08 ± 0.11 | 1.19 ± 0.35 |

| HEETS/Yellow | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.23 ± 0.24 | 1.22 ± 0.12 |

| Marlboro/SmoothRegular | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.15 | 1.11 ± 0.08 |

Uncertainties are estimated to be at the 95% CI.

Table 2.

αfb for Select Brands As Determined by 1H NMR Using CORESTA Puffing Regimea

| Brand/flavor | α fb |

|---|---|

| Parliament | 0.02 ± 0.03 |

| HEETS/Amber | 0.00 |

| HEETS/Yellow | 0.00 |

| HEETS/Turquoise | 0.01 |

| Marlboro/Menthol | 0.01 |

| Marlboro/Smooth Regular | 0.01 |

| Marlboro/Balanced Regular | 0.00 |

| Marlboro | 0.00 |

| Marlboro/Mint | 0.02 |

| Marlboro/Purple Menthol | 0.01 |

Error in the first measurement is assumed to be representative of all measurements.

The very low αfb calculated for IQOS heatsticks herein is consistent with the identification and quantification of acetic acid in the aerosol, as confirmed by NMR and GC-MS, as well as the IQOS flavor additive listing (at levels “no higher than 0.01%”).22 Given the aqueous nature of the aerosol,7 rapid acid-base equilibration occurs. Very low, approximating zero, free-base nicotine in IQOS aerosols differs from findings in Salman et al.,17 who reported a %free-base of 5.7 (αfb = 0.057), nearly 6 times the average αfb measured in work herein, and beyond the upper bound of the 95% CI for the largest αfb value presented herein. A toluene extract of an aqueous extract of the filter pad used for aerosol collection removes Nic from the Nic ⇋ NicH+ equilibrium, which, by Le Chatelier’s principle, must generate more Nic as it continuously migrates from aqueous to toluene phases, leading to an overextraction of Nic and an over-estimation of αfb. Additionally, analysis done by Salman et al.17 may also suffer from inaccuracies due to dilution effects and atmospheric CO2 incursion.11

The αfb ≈ 0 in the aqueous aerosols of HNB products tested is unprecedented when compared to values observed in cigarettes and e-cigarettes.11,28 A comprehensive analysis of αfb values for 12 commercial and reference cigarettes performed by Pankow et al.28 found αfb ranges from 0.010 ± 0.008 to 0.29 ± 0.08, with 9 of 12 < 0.1. Duell et al.11 reported αfb for 11 e-liquids from various brands and found they ranged from 0.03 to 0.84, with only 3 having a value below 0.1.

The NMR method herein is a direct and accurate technique for determining αfb in the aqueous aerosols seen in HNB products. The extremely low Nic values seen in these products likely stem from occurrence of acetic acid, and perhaps other additives, in an aerosol with significant aqueous character. The αfb ≈ 0 may translate to low apparent harshness. It is likely that other similarly designed devices will be comparable in αfb. Low αfb indicates nicotine will almost exclusively be in the PM. The low level of gaseous nicotine in IQOS aerosols may explain the finding that HNB devices are “less satisfying” than traditional cigarettes.29

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. James F. Pankow for editing the manuscript and providing useful discussion. We thank the NIH and the FDA for their support via award R01ES025257. Content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the FDA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- IQOS

I quit ordinary smoking

- HNB

heat-not-burn

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00076.

Materials and methods, statistics, error analysis, and experimental challenges (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Elias J, and Ling PM (2018) Invisible smoke: third-party endorsement and the resurrection of heat-not-burn tobacco products. Tob. Control 27, s96–s101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Caputi TL, Leas E, Dredze M, Cohen JE, and Ayers JW (2017) They’re heating up: Internet search query trends reveal significant public interest in heat-not-burn tobacco products. PLoS One 12 (10), No. e0185735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Tabuchi T, Gallus S, Shinozaki T, Nakaya T, Kunugita N, and Colwell B (2018) Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob. Control 27 (E1), E25–E33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Smith MR, Clark B, Ludicke F, Schaller JP, Vanscheeuwijck P, Hoeng J, and Peitsch MC (2016) Evaluation of the Tobacco Heating System 2.2. Part 1: Description of the system and the scientific assessment program. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 81, S17–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Davis B, Williams M, and Talbot P (2019) iQOS: evidence of pyrolysis and release of a toxicant from plastic. Tob. Control 28, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).St. Helen G, Jacob P III, Nardone N, and Benowitz NL (2018) IQOS: examination of Philip Morris International’s claim of reduced exposure. Tob. Control 27, s30–s36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gasparyan H, Mariner D, Wright C, Nicol J, Murphy J, Liu C, and Procter C (2018) Accurate measurement of main aerosol constituents from heated tobacco products (HTPs): Implications for a fundamentally different aerosol. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 99, 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).El-Hellani A, El-Hage R, Baalbaki R, Salman R, Talih S, Shihadeh A, and Saliba NA (2015) Free-Base and Protonated Nicotine in Electronic Cigarette Liquids and Aerosols. Chem. Res. Toxicol 28 (8), 1532–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pankow JF, Barsanti KC, and Peyton DH (2003) Fraction of free-base nicotine in fresh smoke particulate matter from the Eclipse “cigarette” by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Res. Toxicol 16 (1),23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pankow JF (2001) A consideration of the role of gas/particle partitioning in the deposition of nicotine and other tobacco smoke compounds in the respiratory tract. Chem. Res. Toxicol 14 (11), 1465–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Duell AK, Pankow JF, and Peyton DH (2018) Free-Base Nicotine Determination in Electronic Cigarette Liquids by (1)H NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Res. Toxicol 31 (6), 431–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ferris Wayne G, Connolly GN, and Henningfield JE (2006) Brand differences of free-base nicotine delivery in cigarette smoke: the view of the tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 15 (3), 189–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hurt RD, and Robertson CR (1998) Prying open the door to the tobacco industry’s secrets about nicotine - The Minnesota Tobacco Trial. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association 280 (13), 1173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Fan L, Balakrishna S, Jabba SV, Bonner PE, Taylor SR, Picciotto MR, and Jordt SE (2016) Menthol decreases oral nicotine aversion in C57BL/6 mice through a TRPM8-dependent mechanism. Tobacco Control 25, ii50–ii54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Alpert HR, Agaku IT, and Connolly GN (2016) A study of pyrazines in cigarettes and how additives might be used to enhance tobacco addiction. Tobacco Control 25 (4), 444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chen L (1976) pH of Smoke: A Review, Report N-170, internal document of Lorillard Tobacco Company, p 18, Lorillard Tobacco Company, Greensboro, NC. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Salman R, Talih S, El-Hage R, Haddad C, Karaoghlanian N, El-Hellani A, Saliba NA, and Shihadeh A Free-Base and Total Nicotine, Reactive Oxygen Species, and Carbonyl Emissions From IQOS, a Heated Tobacco Product. Nicotine Tob. Res 2018. Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1093/ntr/nty235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Barsanti KC, Luo W, Isabelle LM, Pankow JF, and Peyton DH (2007) Tobacco smoke particulate matter chemistry by NMR. Magn. Reson. Chem 45 (2), 167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Higashi T, Mai Y, Noya Y, Horinouchi T, Terada K, Hoshi A, Nepal P, Harada T, Horiguchi M, Hatate C, Kuge Y, and Miwa S (2014) A Simple and Rapid Method for Standard Preparation of Gas Phase Extract of Cigarette Smoke. PLoS One 9 (9), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Crouse WEJLF, Johnson LF, and Marmor RS (1980) A Convenient Method for the Determination of Ambient Nicotine. Beitr. Tabakforsch. Int 10 (2), 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Saunders JA, and Blume DE (1981) Quantitation of Major Tobacco Alkaloids by High-Performance Liquid-Chromatography. J. Chromatogr 205 (1), 147–54. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Philip Morris International, What’s in our Heated Tobacco Products? https://www.pmi.com/our-business/about-us/products/making-heated-tobacco-products (accessed November 24, 2018).

- (23).Perfetti TA (1983) Structural Study of Nicotine Salts. Beitr. Tabakforsch. Int 12 (2), 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gee J, Prasad K, Slayford S, Gray A, Nother K, Cunningham A, Mavropoulou E, and Proctor C (2018) Assessment of tobacco heating product THP1.0. Part 8: Study to determine puffing topography, mouth level exposure and consumption among Japanese users. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 93, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Farsalinos K, Yannovits N, Sarri T, Voudris V, and Poulas K (2018) Nicotine Delivery to the Aerosol of a Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Product: Comparison With aTobacco Cigarette and E-Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob. Res 20, 1004–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).McAdam K, Davis P, Ashmore L, Eaton D, Jakaj B, Eldridge A, and Liu C (2019) Influence of machine-based puffing parameters on aerosol and smoke yields from next generation nicotine inhalation products. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 101, 156–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).(2018) Routine Analytical Machine for E-Cigarette Aerosol Generation and Collection - Definitions and Standard Conditions, Cooperation Center for Scientific Research Relative to Tobacco, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Pankow JF, Tavakoli AD, Luo W, and Isabelle LM (2003) Percent free base nicotine in the tobacco smoke particulate matter of selected commercial and reference cigarettes. Chem. Res. Toxicol 16 (8), 1014–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Simonavicius E, McNeill A, Shahab L, and Brose LS Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review. Tob Control 2019. Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.