Abstract

Purpose

Posterior spinal fusion (PSF) activates the fibrinolytic protease plasmin, which is implicated in blood loss and transfusion. While antifibrinolytic drugs have improved blood loss and reduced transfusion, variable blood loss has been observed in similar PSF procedures treated with the same dose of antifibrinolytics. However, both the cause of this and the appropriate measures to determine antifibrinolytic efficacy during high-blood-loss spine surgery are unknown, making clinical trials to optimize antifibrinolytic dosing in PSF difficult. We hypothesized that patients undergoing PSF respond differently to antifibrinolytic dosing, resulting in variable blood loss, and that specific diagnostic markers of plasmin activity will accurately measure the efficacy of antifibrinolytics in PSF.

Methods

A prospective study of 17 patients undergoing elective PSF with the same dosing regimen of TXA was conducted. Surgery-induced plasmin activity was exhaustively analyzed in perioperative blood samples and correlated to measures of inflammation, bleeding, and transfusion.

Results

While markers of in vivo plasmin activation (PAP and D-dimer) suggested significant breakthrough plasmin activation and fibrinolysis (P < 0.01), in vitro plasmin assays, including TEG, did not detect plasmin activation. In vivo measures of breakthrough plasmin activation correlated with blood loss (R2 = 0.400, 0.264; P < 0.01), transfusions (R2 = 0.388; P < 0.01), and complement activation (R2 = 0.346, P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Despite all patients receiving a high dose of TXA, its efficacy among patients was variable, indicated by notable intra-operative plasmin activity. Markers of in vivo plasmin activation best correlated with clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that the efficacy of antifibrinolytic therapy to inhibit plasmin in PSF surgery should be determined by markers of in vivo plasmin activation in future studies.

Level of evidence

Level II-diagnostic.

Keywords: Posterior spinal fusion, Antifibrinolytic, TXA, Elective surgery, Plasmin activity

Introduction

Posterior spinal fusion (PSF) provokes significant blood loss proportional to the number of levels fused and osteotomies [1, 2]. This bleeding is, in part, due to intra-operative activation of fibrinolytic enzyme plasmin, and therefore, the use of antifibrinolytic drugs during invasive high blood-loss spine surgery, such as PSF, has significantly improved clinical outcomes by reducing blood loss and transfusion [3, 4] (Fig. 1A, B). Furthermore, studies have indicated that antifibrinolytics also reduce surgery-induced coagulopathy and systemic inflammation [5–7]. Anecdotally, surgeons have noted that despite the same antifibrinolytic dosing protocol and similar surgical procedure, patients respond differently. Specifically, some patients experience more blood loss and require more transfusions than others, despite similar dosing of antifibrinolytics. The variability between the pharmacodynamic response to antifibrinolytics administered intra-operatively has not been well described (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

A PSF in the absence of antifibrinolytic treatment provokes significant blood loss and coagulopathy, requiring transfusions. B The administration of antifibrinolytics during PSF greatly reduces blood loss, inflammation, coagulopathy, and transfusion requirements. C In PSF treated with antifibrinolytics, it’s unclear how different patients respond to the same dosing scheme, how plasmin activation in the presence of an antifibrinolytic might affect blood loss and inflammation, and how best to measure the efficacy of antifibrinolytics to prevent negative outcomes

We hypothesized that there is variability in the clinical efficacy of antifibrinolytics and that this variability can be directly measured by “breakthrough plasmin activity,” or plasmin activity observed despite antifibrinolytic administration. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a prospective study in patients undergoing PSF surgeries treated with a high dose of TXA and examined breakthrough plasmin activity, measured by different diagnostic methods relative to both downstream pathways activated by plasmin, including primary clinical outcomes, of blood loss and transfusion and secondary clinical outcomes of coagulopathy and systemic inflammation. The primary goal of this study was to determine if breakthrough plasmin activity during antifibrinolytic administration is associated with these variable clinical outcomes and the secondary goal was to determine which diagnostic measures of breakthrough plasmin activity accurately reflect antifibrinolytic efficacy based on these outcomes.

Methods

Study design

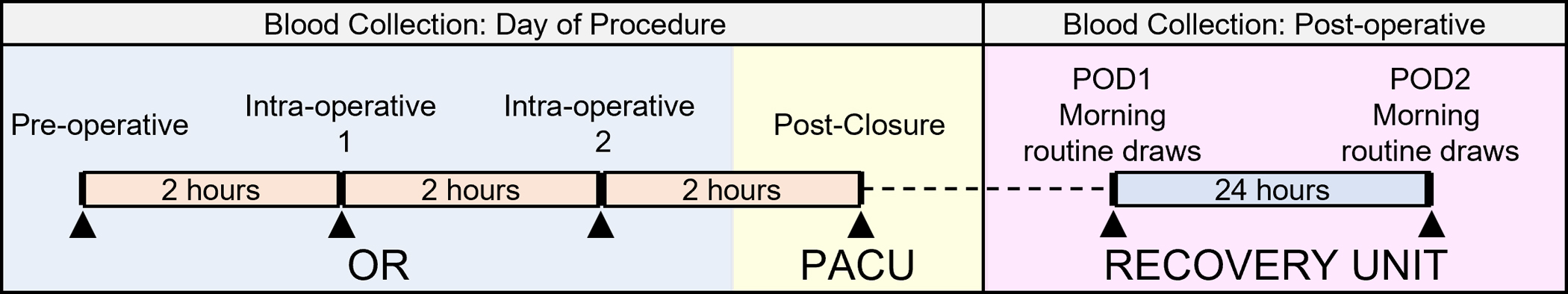

Following approval from the Institutional Review Board (#181982, NCT03741023), patients aged 7–18 years old with either neuromuscular or idiopathic scoliosis undergoing elective PSF were recruited to quantify changes in intra-operative plasmin activation in a heterogeneous population. All procedures occurred between December 2019 and March 2021 at a single pediatric medical center. Blood was collected during hospitalization as outlined in Fig. 2. Collected blood was centrifuged at 1500×g and 13,000×g for 15 min each to isolate platelet-poor plasma (PPP) for further analysis. Patient demographic information, including age, sex, weight, height, ethnicity, and comorbidities were collected from the electronic health record (EHR). Additionally, procedural information, including the number of vertebrae fused, number of osteotomies, operative time, and routine lab blood and coagulation measurements associated with the procedure were collected from the EHR.

Fig. 2.

Blood collection procedures for the study

Patient care and routine TXA administration

PSF surgeries were performed by two orthopaedic surgeons and one anesthesiologist. Prior to incision, patients received an intravenous (IV) bolus dose of 100 mg/kg TXA for patients < 20 kg and 2000 mg TXA for patients ≥ 20 kg and a maintenance TXA IV infusion of 10 mg/kg/h for patients < 50 kg or 500 mg/h for patients ≥ 50 kg. Red blood cell salvage was routinely given back when possible. Idiopathic scoliosis patients who underwent PSF followed a standardized anesthesia protocol consisting of lidocaine, propofol, and sufentanil infusions to allow for neuro-monitoring. Anesthesia protocols for neuromuscular scoliosis patients were adjusted based on specific surgical needs. If neuro-monitoring was not required in neuromuscular scoliosis patients, general anesthetic consisted of inhaled anesthetic agents and muscle relaxant rocuronium.

Plasmin activity assays

Thrombelastography (TEG)

For a subset of patients enrolled in this study (N = 8), TEG (TEG 5000, Haemonetics, Boston, MA) was immediately performed in whole blood in duplicate at each time point as previously described [8].

Clot-independent streptokinase plasmin activity assay

To measure plasmin activation in a clot-dependent manner using bacterial plasmin activator streptokinase (SK), patient plasma samples and control pooled plasma (George King Bio-Medical Inc., Overland Park, KS) were diluted 1:5, 1:10, and 1:20 in HEPES buffer. Increasing concentrations of TXA (Pfizer, New York, NY) were added to control plasma or purified plasminogen (Haemtech, Essex Junction, VT). Diluted plasma (or purified plasminogen) and fluorogenic substrate (H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-AFC, Anaspec, Fremont, CA) were added in triplicate to a 96-well plate. Plasmin activation was initiated by the addition of 0.5 U/μL bacterial streptokinase (SK) (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) and fluorescence was measured every 30 s for 1 h using a Synergy 2 plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT). Rates of plasmin generation were calculated based on change in fluorescence over time and were reported as a percent of control pooled plasma [9].

Plasmin reporter/antigen, coagulation antigen, endothelial activation, and inflammasome assays

ELISA and multiplex analysis

PPP samples diluted 1:2 were analyzed by Luminex-based custom multiplex to detect D-dimer, P-selectin, CD40L, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, thrombomodulin, L-selectin, uPAR, uPA (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Plasmin-antiplasmin (PAP) complexes were measured by ELISA at a 1:10 dilution (Technozym Diapharma, West Chester, OH). Plasminogen antigen levels were measured by ELISA (Molecular Innovations, Novi, MI) at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Blood-loss calculations

Blood-loss was calculated using both a hematocrit-based estimated red cell mass (ERCM) deficit normalized as a percent of total blood volume (% TBV) and normalized blood product transfused (nBPT) [10, 11]. nBPT was calculated as the volume of intra-operative RBC product, both autologous (cell salvage) and allogeneic (packed RBCs), normalized to patient weight (mL/kg). The anesthesia post-operative record of estimated blood loss (EBL) was also noted from the patient charts.

Statistical analysis

Paired, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests were used to evaluate differences between sample timepoints from the pre-operative values with Dunnett’s post hoc correction for multiple comparisons. Pearson correlations were used to evaluate associations between patient variables. All statistical calculations and figures were generated with GraphPad Prism version 8.0.0 (www.graphpad.com).

Results

Cohort description

Across the 17 patients enrolled in this study undergoing PSF, 9 (53%) patients were diagnosed with neuromuscular scoliosis, while the remaining 8 (47%) patients were diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis. This cohort included 13 females (76%) and 4 males (26%) ranging from 10 to 18 years of age with a median BMI of 19.8 (range: 16.5–36.2). The average length of the procedure for these patients was 4.9 h (range: 3.2–7.6), and the median number of levels fused was 13 (range: 8–16), with a median of 4 (range: 0–14) osteotomies performed per patient. Cohort demographics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics

| Total (N = 17) | Idiopathic (N = 8) | Neuromuscular (N = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 13 (10–18) | 15 (11–18) | 12 (10–17) |

| Sex (male/female) | 4/13 | 1/7 | 3/6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 19.8 (16.5–36.2) | 22.2 (16.7–32.9) | 19.8 (16.5–36.2) |

| Length of procedure (min) | 292 ± 71.3a | 262 ± 66.4a | 319 ± 67.6a |

| Levels fused | 13 (8–16) | 11.5 (8–16) | 16 (9–16) |

| Osteotomies | 4 (0–14) | 4 (0–8) | 3(0–14) |

| Length of stay (days) | 3.8 ± 1.8† | 2.8 ± 0.7a | 4.7 ± 1.9a |

Median (range), unless otherwise indicated

Mean ± SD

Blood-loss measurements and transfusions

The mean ERCM deficit was 17.9% TBV (range: 7.7–51.8) and the mean nBPT was 6.0 mL/kg (range: 0–17.9). On average, patients with idiopathic scoliosis lost less blood than those with neuromuscular scoliosis (17.0 vs 19.7% TBV, respectively), consistent with previous studies [2]. Across all 17 patients, 16/17 (94.1%) received autologous red blood cell salvage during the procedure, and 3/17 (17.6%) received allogeneic packed red blood cell (pRBC) transfusion. Presurgical lab values, blood loss measurements, and transfusions are highlighted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lab values and blood loss

| Total (N = 17) | Idiopathic (N = 8) | Neuromuscular (N = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Pre-surgical lab values | |||

| PT (s) | 13.7 ± 0.6 | 13.7 ± 0.7 | 13.6 ± 0.5 |

| aPTT (s) | 30.6 ± 2.9 | 30.8 ± 3.1 | 30.3 ± 2.7 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 311 ± 82.6 | 323 ± 98.2 | 298 ± 68.0 |

| Platelet count (L−1) | 273 ± 72.5 | 284 ± 79.3 | 262 ± 69.0 |

| EBL (mL) | 583.5 ± 274.4 | 519.6 ± 186.5 | 633.2 ± 329.7 |

| EBL (% TBV) | 20.5 ± 10.8 | 12.2 ± 4.1 | 23.6 ± 5.1 |

| ERCM deficit (% TBV) | 17.9 ± 10.0 | 17.0 ± 14.3 | 19.7 ± 4.4 |

| Received cell salvage N (%) | 16 (94) | 8 (100) | 8 (89) |

| Cell salvage (mL) | 166 ± 101 | 175 ± 117 | 157 ± 88.3 |

| Received pRBC N(%) | 3 (18) | 1 (13) | 2 (22) |

| nBPT (mL/kg) | 6.0 ± 8.0 | 5.7 ± 10.2 | 6.2 ± 6.1 |

Mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated

ERCM estimated red cell mass, EBL estimated blood loss, cell salvage autologous red cells, pRBC allogeneic packed red blood cells, nBPT normalized blood product transfused, TBV total blood volume

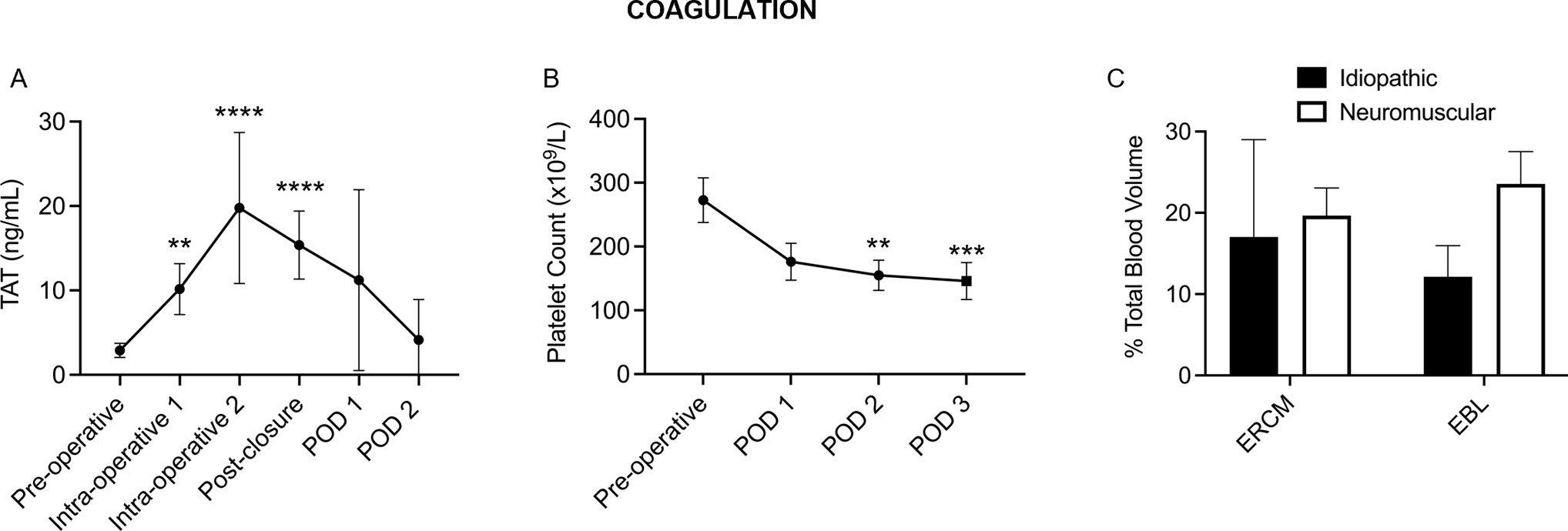

Intra-operative and post-operative coagulation

Consistent with other large cohort trials [2, 12], all patients exhibited significant coagulation activation indicated by intra-operative increases in thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) complexes and decreases in platelet count following the surgery (Fig. 3A, B). TEG analysis of whole blood in a subset of patients (N = 8) indicated a mild decrease in coagulation potential parameters within normal range throughout the procedures (Figure S1A–D). Significant blood loss occurred in both idiopathic and neuromuscular scoliosis patients with an average blood loss of > 17% TBV (range: 8–52%) (Fig. 3C). Markers of platelet and endothelial activation (P-selectin, CD40L, thrombomodulin) and levels of endogenous anticoagulant protein C did not change significantly throughout hospitalization (Figure S2).

Fig. 3.

Posterior spinal fusion surgery significantly activates coagulation, causing a detectable increase in A TAT throughout the case, B a postoperative drop in platelet count. C Both idiopathic and neuromuscular patients exhibited significant blood loss throughout the procedures

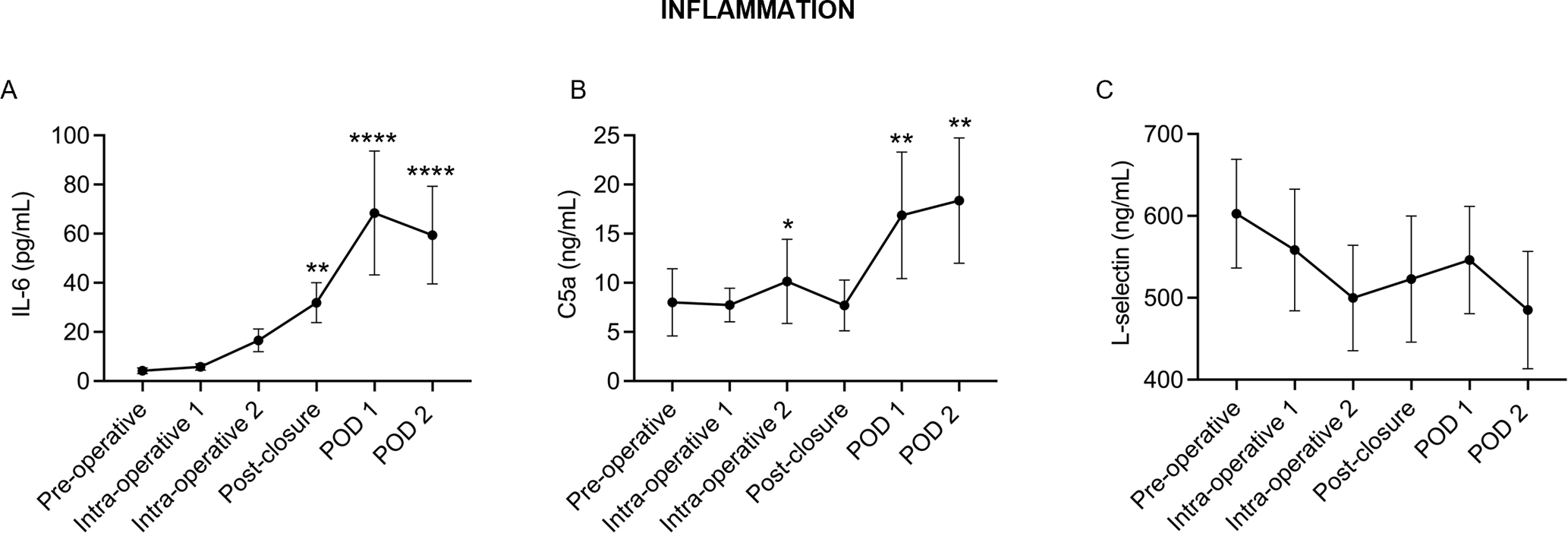

Inflammation

In this cohort, inflammatory cytokine IL-6 peaked at POD1, before beginning to return to baseline by POD2 (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous studies [5]. PSF patients exhibited a transient peak of complement activation intraoperatively and prolonged elevation of C5a at POD1 and POD2 (Fig. 4B). Soluble L-selectin, a common marker of leukocyte activation, did not change significantly throughout hospitalization (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

A Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 peaked by POD1 while B complement activation peaked intra-operatively with reactivation occurring on POD1 and POD2. C No significant changes in leukocyte activation marker, L-selectin, occurred during hospitalization. N = 17, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with pre-operative values. Points represent the mean with 95% confidence intervals

Intra-operative changes in plasmin activity and fibrinolysis

Throughout the PSF procedure and TXA administration, different measures of plasmin activity demonstrated conflicting results. Clot lysis by plasmin on TEG (LY30, N = 8) decreased intra-operatively and returned above baseline by POD1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, plasmin activation potential measured by a clot-independent plasmin activity assay decreased intra-operatively and did had not returned to baseline by POD2 (Fig. 5B). In contrast, there was a detectable, significant increase in plasmin–antiplasmin (PAP) complexes, a marker that reflects the presence of plasmin activation in a patient. Increased PAP occurred as early as 2 h post-incision and reached a maximum at approximately 6 h post-incision (Fig. 5C). Significant fibrinolysis also occurred in this cohort of PSF patients, indicated by a 3–6-fold intra-operative increase in D-dimer that remained elevated throughout hospitalization (Fig. 5D). Despite consistent TXA dosing across all patients, variable breakthrough plasmin activation occurred intra-operatively, and while trauma studies have suggested that TXA loses efficacy within hours of an injury due to an increase in circulating urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA), we did not observe significant differences in free uPA or its receptor (suPAR) in this study (Figure S2A–B). Blood plasminogen antigen levels, which are unaffected by therapeutic TXA, also decreased intra-operatively (Fig. 5E) and were correlated with the clot-independent plasmin activity measurement (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

A Fibrinolysis measured by TEG clot lysis (LY30, N = 8) and B SK-based plasmin activity decreased in the intra-operative period during TXA administration. C Plasmin activation (PAP) and D fibrinolysis (D-dimer) increased significantly during the procedure. E Plasma plasminogen antigen levels decrease intra-operatively and remain decreased through POD2 N = 17, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with pre-operative values. Points represent the mean with 95% confidence intervals. F Plasminogen antigen levels strongly correlated with SK-based plasmin activity quantification (R2 = 0.637, P < 0.0001)

Intra-operative plasmin activity and outcomes

The magnitude of the intra-operative increase in plasmin activation (PAP) correlated with nBPT (R2 = 0.388, P = 0.007) and ERCM deficit (R2 = 0.400, P = 0.006). Furthermore, the intra-operative increase in D-dimer weakly correlated with ERCM deficit (R2 = 0.264, P = 0.035) (Table 3), and D-dimer levels significantly correlated with activation of the complement pathway (C5a) throughout hospitalization (R2 = 0.364, P = 0.0001). Intra-operative blood loss variability in PSF patients has been attributed to BMI, number of osteotomies, number of levels fused, and differing surgical technique [1, 13]. In this cohort, BMI and number of osteotomies were not associated with ERCM deficit (R2 = 0.109, 0.005, P = 0.201, 0.775, respectively), and there were no significant differences in total blood loss measurements between the two surgeons performing the procedures (P = 0.475). However, the number of levels fused during the procedure was weakly associated with ERCM deficit (R2 = 0.308, P = 0.02). While the TXA dosing varied based on patient weight, there was no association between TXA dosing per kilogram of body weight and ERCM deficit for either bolus (R2 = 0.190, P = 0.09) or continuous (R2 = 0.162, P = 0.100) administration.

Table 3.

Plasmin activity measures, blood loss and inflammation

| nBPT | ERCM | C5a | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| PAP | R2 = 0.388 | R2 = 0.400 | R2 = 0.021 |

| P = 0.008 | P = 0.007 | P = 0.402 | |

| D-dimer | R2 = 0.146 | R2 = 0.264 | R2 = 0.346 |

| P = 0.131 | P = 0.035 | P = 0.0001 | |

| Plasmin Activity | R2 = 0.114 | R2 = 0.129 | R2 = 0.022 |

| P = 0.186 | P = 0.157 | P = 0.781 | |

P value indicates slope of the correlation is significantly different than zero for each variable

nBPT normalized blood product transfused, ERCM estimated red cell mass deficit, C5a complement 5a (active), PAP plasmin–antiplasmin

Discussion

Controlled musculoskeletal injury in PSF leads to physiologic activation of coagulation and inflammation to contain the damage. However, dysregulation of this containment system can provoke adverse outcomes such as excessive bleeding and systemic inflammation [2, 14, 15]. A key pathophysiologic event that instigates this process is the intra-operative activation of the fibrinolytic protease plasmin [5]. Following injury, plasminogen binds to injured tissue [16–18] where it is later activated to plasmin to support repair of musculoskeletal tissue [18–21]. However, at a specific threshold of injury severity, early, excessive plasmin activation occurs contributing to activation of coagulation, inflammation and their associated adverse outcomes [22–26]. Consequently, the use of antifibrinolytics to inhibit this plasmin activity has revolutionized elective surgical procedures, reducing the effects of pathologic plasmin activity on surgical outcomes. In this study, we detected variable intra-operative breakthrough plasmin activity in PSF patients which correlated not only with blood loss and transfusions but also with systemic inflammation.

In this study, diagnostic measures of plasmin activity demonstrated conflicting results, consistent with previous studies [27]. Plasmin diagnostic measurements are subject to a multitude of variables that may cloud the clinical interpretation of these results. For instance, measures that reflect current or previous activation of plasmin (PAP) or fibrinolysis (D-dimer) within this cohort demonstrated significant intra-operative plasmin activity (Fig. 6A, B). In contrast, clot lysis on TEG (LY30), which measures plasmin activation and fibrinolytic potential in whole blood, is sensitive to the presence of antifibrinolytics and was decreased intra-operatively during TXA administration (Fig. 6A, B). Additionally, a clot-independent measure of plasmin activation potential (SK assay) demonstrated diminished plasmin activity throughout the surgery that was attributed to a considerable decrease in circulating plasminogen levels (Fig. 6A). This is the first study to demonstrate that plasminogen is redistributed from the blood during and after surgery, possibly due to activation and/or binding to the site of injury, and that a redistribution of plasminogen from the blood to this extent may alter plasmin activity assays. This finding has an impact on the use of plasmin activity assays to make clinical decisions in orthopaedics as the amount of plasminogen redistribution following injury has been found to be proportional to the amount of injured tissue [28, 29]. Therefore, in the setting of a large surgery, such as PSF, an apparent decrease in plasmin activity in blood may not reflect plasmin activity at the site of tissue damage where bleeding is occurring, which can be detected by D-dimer and PAP measurements. From these findings, we strongly recommend that measures of plasmin activity potential, such as TEG, not be used as the sole determinant of the efficacy of antifibrinolytics as they may be subject to confounding variables such as the presence of the antifibrinolytic itself, as well as plasminogen redistribution.

Fig. 6.

A While LY30 and plasminogen decrease or remain level during PSF procedure, PAP and D-dimer increase significantly. PAP and D-dimer also follow different time courses during and after surgery. PAP increases prior to fibrinolysis (D-dimer) but is undetectable in the post-operative period until POD2, while D-dimer increases intra-operatively and remains elevated in the post-operative period. (Values expressed as a percent of baseline values for each patient). B Different assays used to measure plasmin activity and fibrinolysis depict different aspects of plasmin biology

In this study, we observed a heterogeneous response to antifibrinolytics in this cohort, measured by elevation of PAP and D-dimer during PSF, indicating breakthrough plasmin activation with the TXA dosing regimen that was not detected by TEG. However, the clinical significance of this is undefined: an intra-operative increase in PAP or D-dimer in isolation does not predict adverse outcomes. Therefore, we demonstrated that an intra-operative increase in plasmin activation, measured by PAP and D-dimer, was associated with measures of blood loss and transfusion in this cohort. Additionally, we found that increases in D-dimer were associated with complement activation, which is consistent with what is known about plasmin roles in inflammation [6, 7, 25]. While inflammation is currently not a significant concern following PSF, recent studies have demonstrated that regulating the inflammatory response to surgical injury can accelerate tissue repair and prevent post-operative infections [14, 30]. Together, these associations suggest that breakthrough plasmin activation, detectable by PAP or D-dimer measurements, may contribute to blood loss and inflammation.

This study was limited by a small cohort and the use of a single antifibrinolytic dosing strategy, but despite this, we observed significant differences in breakthrough plasmin activation between patients, which correlated with clinical outcomes. This study intentionally included both AIS and neuromuscular scoliosis patients as these groups are known to have differing clinical outcomes [2], providing a heterogeneous population in which to determine the clinical significance of breakthrough plasmin activity [2]. Unlike other studies in PSF [1, 13], BMI and number of osteotomies were not associated with blood loss likely due to inadequate power in this small, heterogeneous cohort. The number of levels fused these patients was associated with blood loss and transfusion, and therefore, breakthrough plasmin activity may be proportional to the magnitude of tissue injury. This factor could be considered in clinical trials along with patient weight. In this study, there was no control group that did not receive TXA, because numerous clinical trials have already demonstrated the efficacy of antifibrinolytics to reduce blood loss compared with no treatment. Rather, the goals of this study were (1) to determine if patients exhibit variable responses to TXA treatment measured by markers of plasmin activity and (2) to determine which diagnostic markers of plasmin activity best reflect antifibrinolytic efficacy based on clinical outcomes, including blood loss, to inform future, large cohort studies to optimize antifibrinolytics by limiting intra-operative plasmin activation and associated adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

PSF patients exhibit variable responses to antifibrinolytics which correlate with blood loss, transfusions, and inflammation. Plasmin reporter measurements (D-dimer or PAP) provide the most sensitive detection of plasmin activity to best determine the efficacy of antifibrinolytic dosing during PSF. Significant changes in PAP or D-dimer may indicate breakthrough plasmin activation during antifibrinolytic administration. However, these findings should be measured in relation to adverse outcomes (e.g., blood loss) to determine if detected plasmin activation is clinically meaningful before altering the dosing regimen. This prospective study confirms variable pharmacodynamic responses to antifibrinolytics during PSF and provides rationale for the use of specific diagnostics to optimize antifibrinolytic efficacy to attenuate blood loss, transfusion, and inflammation in high blood loss spine surgeries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank members of the Division of Pediatric Orthopaedics, the Division of Pediatric anesthesiology, and the numerous pediatric nurses for their care of patients at our institution; this work would not have been possible without their dedication. We would also like to thank members of the Schoenecker laboratory and the Department of Orthopaedics, specifically Vaibhav Tadepalli, J. Court Reese and Julie Shelton for their contributions to this work, and Drs. David Gailani, Joey Barnett, Brian Wadzinski, and Alan Brash for their feedback and direction. Finally, we would also like to thank our family and friends for their continual support.

Funding

Funding for this study was supported by the Caitlin Lovejoy Fund, the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Department of Orthopaedics (JGS), the Katherine Dodd Faculty Scholar Fund (AJB), the Vanderbilt Center for Musculoskeletal Research Faculty Award (MTD), the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Research Immersion Program (LJM), UL1 TR002245 (MTD) and NHLBI-F31HL149340-02 (BHYG).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest JGS has funding unrelated to this work from the NIH (NIGMS), the Department of Defense, and OrthoPediatrics. All other authors have nothing further to disclose.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s43390-022-00489-6.

Code availability Not applicable.

Ethics approval All study procedures were previously approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB #181982, Clinicaltrials.gov #NCT03741023) and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards described in the updated Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate Informed consent was obtained from legal guardians and/or patients (depending on age) to participate in this study.

Consent for publication All patients included in this study provided informed consent to publish study findings.

Availability of data and materials

The authors certify that the data support the results presented within this study and agree to provide materials upon request.

References

- 1.Dong Y, Tang N, Wang S et al. (2021) Risk factors for blood transfusion in adolescent patients with scoliosis undergoing scoliosis surgery: a study of 722 cases in a single center. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannan S, Meert KL, Mooney JF et al. (2002) Bleeding and coagulation changes during spinal fusion surgery: a comparison of neuromuscular and idiopathic scoliosis patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med 3(4):364–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goobie SM, Zurakowski D et al. (2018) Tranexamic acid is efficacious at decreasing the rate of blood loss in adolescent scoliosis surgery: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg Am 100(23):2024–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha IK, Ruan TY, Lin L et al. (2021) The efficacy and safety of high-dose tranexamic acid in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 16(1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Wang LN, Yang X et al. (2021) The effect of multiple-dose oral versus intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing postoperative blood loss and transfusion rate after adolescent scoliosis surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Spine J 21(2):312–320. 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett CD, Moore HB, Kong YW et al. (2019) Tranexamic acid mediates proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling via complement C5a regulation in a plasminogen activator-dependent manner. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 86(1):101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu KT, Siu KK, Ko JY et al. (2019) Tranexamic acid reduces total blood loss and inflammatory response in computer-assisted navigation total knee arthroplasty. Biomed Res Int 2019:5207517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao H, Cai X, Liu N et al. (2020) Thromboelastography as a tool for monitoring blood coagulation dysfunction after adequate fluid resuscitation can predict poor outcomes in patients with septic shock. J Chin Med Assoc 83(7):674–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherry S (1954) The fibrinolytic activity of streptokinase activated human plasmin. J Clin Investig 33(7):1054–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang JK, Lee SW, Baik MW et al. (1998) Perioperative specific management of blood volume loss in craniosynostosis surgery. Child’s Nerv Syst 14(7):297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker CE, Marvi T, Austin TM et al. (2018) Dilutional coagulopathy in pediatric scoliosis surgery: a single center report. Paediatr Anaesth 28(11):974–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urgery S, Ncorporated I, Bosch P et al. (2016) coagulation profile of patients with adolescent spinal fusion. J Bone Jt Surg 88:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villavicencio A, Lee Nelson E, Rajpal S et al. (2019) The impact of BMI on operating room time, blood loss, and hospital stay in patients undergoing spinal fusion. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 179(January):19–22. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida K (2019) Post-surgical immune suppression: another target to improve postoperative outcomes. J Anesth 33(6):625–627. 10.1007/s00540-019-02651-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smajic J, Tupkovic LR, Husic S et al. (2018) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome in surgical patients. Med Arch (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina) 72(2):116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samson AL, Borg RJ, Niego B et al. (2009) A nonfibrin macromolecular cofactor for tPA-mediated plasmin generation following cellular injury. Blood 114(9):1937–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulniute R, Shen Y, Guo Y et al. (2016) Plasminogen is a critical regulator of cutaneous wound healing. Thromb Haemost 2016(8):1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson BHY, Duvernay MT, Moore-Lotridge SN et al. (2020) Plasminogen activation in the musculoskeletal acute phase response: injury, repair, and disease. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 4(4):469–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suelves M, López-Alemany R, Lluís F et al. (2002) Plasmin activity is required for myogenesis in vitro and skeletal muscle regeneration in vivo. Blood 99(8):2835–2844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuasa M, Mignemi NA, Nyman JS et al. (2015) Fibrinolysis is essential for fracture repair and prevention of heterotopic ossification. J Clin Investig 125(8):3117–3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mignemi NA, Yuasa M, Baker CE et al. (2017) Plasmin prevents dystrophic calcification after muscle injury. J Bone Miner Res 32(2):294–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chin TL, Silliman CC, Banerjee A (2015) Hyperfibrinolysis, physiologic fibrinolysis, and fibrinolysis shutdown: the spectrum of postinjury fibrinolysis and relevance to antifibrinolytic therapy. J Acute Care Surg 77(6):811–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mcnicol ED, Tzortzopoulou A, Schumann R et al. (2016) Antifibrinolytic agents for reducing blood loss in scoliosis surgery in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD006883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White NJ (2014) Mechanisms of trauma-induced coagulopathy. Curr Opin Hematol 21(5):404–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maas C (2019) Plasminflammation—an emerging pathway to bradykinin production. Front Immunol 10(AUG):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heissig B, Salama Y, Osada T et al. (2021) The multifaceted role of plasminogen in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 22(5):1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosch P, Kenkre TS, Soliman D et al. (2019) Comparison of the coagulation profile of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients undergoing posterior spinal fusion with and without tranexamic acid. Spine Deform 7(6):910–916. 10.1016/j.jspd.2019.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson BH, Moore-Lotridge SN, Mignemi NA et al. (2017) The consumption of plasminogen following severe burn and its implications in muscle calcification. Exp Biol FASEB 31:390–394 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson BH, Wollenman C, Moore-Lotridge SN et al. (2021) Plasmin drives burn-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Clin Investig Insight 6(23):1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Draxler DF, Yep K, Hanafi G et al. (2019) Tranexamic acid modulates the immune response and reduces postsurgical infection rates. Blood Adv 3(10):1598–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors certify that the data support the results presented within this study and agree to provide materials upon request.