Abstract

Background

Inadequate support for underrepresented-in-medicine physicians, lack of physician knowledge about structural drivers of health, and biased patient care and research widen US health disparities. Despite stating the importance of health equity and diversity, national physician education organizations have not yet prioritized these goals.

Aim

To develop a comprehensive set of Health Justice Standards within our residency program to address structural drivers of inequity.

Setting

The J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program of Emory University is an academic internal medicine residency program located in Atlanta, Georgia.

Participants

This initiative was led by the resident-founded Churchwell Diversity and Inclusion Collective, modified by Emory IM leadership, and presented to Emory IM residents.

Program Description

We used an iterative process to develop and implement these Standards and shared our progress with our coresidents to evaluate impact.

Program Evaluation

In the year since their development, we have made demonstrable progress in each domain. Presentation of our work significantly correlated with increased resident interest in advocacy (p<0.001).

Discussion

A visionary, actionable health justice framework can be used to generate changes in residency programs’ policies and should be developed on a national level.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08047-0.

KEY WORDS: medical education, health equity, racism in medicine

INTRODUCTION

In 2003, the landmark National Academies report “Unequal Treatment” detailed how physician homogeneity, segregated healthcare, bias, and other forms of systemic racism lead to poorer medical care for racial/ethnic minoritized groups in the USA.1 In the subsequent two decades, organizations that govern physician education have released numerous statements about the importance of health equity and physician diversity,2,3 but little has changed. Our workforce remains overwhelmingly White and wealthy,4,5 and the disproportionately small number of Black and Hispanic/Latinx physicians are compensated and promoted at a much lower rate than their White counterparts.6 Comprehensive education on the structural violence described in “Unequal Treatment” and how to effectively advocate for change is not a national requirement of American medical education nor is it rigorously tested on standardized examinations.

The spring of 2020 saw a surge in physician activism as racist police brutality and health disparities in COVID-197 made the connections between systemic racism, policy, and health stark. The White Coats for Black Lives (WC4BL) movement—started by medical students in 2014 following the police murders of Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and Michael Brown—gained broad acknowledgement within the medical community.

This paper describes the efforts of residents and faculty within the J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Program at Emory University (Emory IM) to develop and implement a rigorous health equity framework for our program—the Health Justice Standards (“Standards”)—that articulates our shared vision and encourages accountability.

SETTING AND PARTICIPANTS

Of Emory IM’s 56 most recent incoming residents, 27% identified as Asian-American, 13% Black, 7% Hispanic/Latino, 50% White, and 3% did not respond. Our resident-led affinity group, the Churchwell Diversity and Inclusion Collective (CDIC), developed an Advocacy Branch in the spring of 2020 that includes approximately 80 members. CDIC residents engaged with multiple Emory Department of Medicine (DOM) stakeholders, including our Program Director, DEI Council leadership, and the DOM Chair in co-constructing the Standards.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

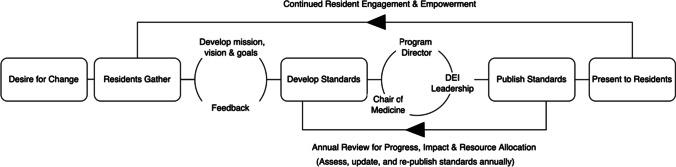

Following a grassroots approach,8 we conducted a needs assessment in spring 2020 by holding three 1 hour sessions. We invited all Emory IM residents, asked what they hoped to gain from CDIC Advocacy, and used this to draft mission, vision, and values statements. We circulated these to all Emory IM residents for anonymous feedback and invited any interested resident to co-lead the group using a rotating leadership model. We then conducted a literature review of strategic planning efforts by similar groups to build concrete, measurable goals. WC4BL’s Racial Justice Report Card,9 which scores medical schools using an equity-focused rubric, formed the backbone of our strategic planning. In summer 2020, we modified these approaches to build the Standards, which articulated Emory IM’s vision for equitable healthcare and physician educational systems. We discussed the Standards with faculty and staff members of Emory’s DEI Council. We then negotiated with program and departmental leadership to modify them into their current form, which can be found on our program website10 and in Appendix 1. Figure 1 summarizes our process.

Figure 1.

Process map for creation of the Health Justice Standards.

Our Standards are organized into five domains: Representation, Support, Education, Patient Care, and Research. Representation focuses on building population parity in the physician workforce by recruiting diverse residents/faculty. Support focuses on institutionalizing support for systematically marginalized physicians. Education focuses on building a health justice curriculum that parallels the rigor of the existing biomedical curriculum. Patient Care emphasizes providing equitable care to all patients, and Research focuses on ensuring that studies conducted at Emory identify race as a social construct and do not misattribute the driver of health inequities to biological differences instead of racism.

Under each domain, we articulate Standards for just healthcare and education systems. Two sections are included within each (1) Current Status, which documents recent progress, and (2) Planned Actions, which documents annual goals. This framework is reviewed and updated annually.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Since publication of the Standards in summer 2021, we have achieved at least one planned action in each area (Appendix 2). These efforts include institutional support for an LGBTQ+ affinity group, discrimination reporting, development of a monthly core Health Justice Curriculum (Appendix 4, Table 1), and improvements to Emory IRB protocols, including a new requirement that researchers define race and its use in their studies.

In April 2022, CDIC Advocacy presented the Standards to Emory IM residents as a required “noon conference.” At different points in the presentation, we solicited resident perceptions regarding (1) US healthcare and medical education systems, (2) physicians’ roles in improving them, (3) advocacy careers, and (4) advocacy barriers through Poll Everywhere anonymous survey questions. This study was IRB exempt. The full questions text is listed in Appendix 4, Table 2.

We tabulated the distribution of responses by generating descriptive statistics through Microsoft Excel. For questions comparing attitudes at the beginning and end of the presentation, we used SPSS to perform unpaired two-sided t-tests. We did not run paired t-tests because Poll Everywhere provides the sum of responses to each Likert category rather than individual-level responses. The data were generally not normally distributed, though the response rate of >20 allowed us to use the t-test.

Approximately 43 residents were required to attend conference unless they had the day off or an urgent patient care issue. Forty-one residents participated in the survey, although some did not respond to all questions. On a scale of 0 (“worst possible system”) to 5 (“best possible system”), mean ratings were 2.1 (n=28) for our healthcare system and 2.3 (n=31) for our medical education system. On a scale of 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“it’s part of our professional duty”), 74% of respondents selected 4 or 5 when asked, before our presentation, the degree to which physicians are responsible for improving our healthcare system (n=19). In the post-presentation survey, 80% selected 4 or 5 (n=25). Pre-presentation, 84% selected 4 or 5 when asked the degree to which physicians are responsible for improving our medical education system (n=19), and 86% selected 4 or 5 post-presentation (n=30). Neither increase was statistically significant. Before our presentation, the average response to the question “How interested are you in advocating for improvements to our healthcare and/or medical education systems?” (0 indicating no interest and 7 indicating strong interest) was a 4.2 (SD ± 1.8, n=24), roughly corresponding to the belief “I would like to get involved in advocacy, but I don't know how.” Post-presentation, the average response was 5.3 (SD ± 1.4, n=30), corresponding to “I'm ready to get involved and know how, but I haven't started yet.” This increase was statistically significant (p <0.001). Sixty-four percent of residents (18/28) responded to an open-ended question that “time” was the most significant barrier to participation in advocacy. Full survey results and scale descriptions are presented in Appendix 3.

DISCUSSION

The Emory IM Standards represent a sustainable collaboration between trainees and program leadership that balances vision with practicality. This effort has invigorated both trainees and faculty, aided in program recruitment of diverse residents, and streamlined siloed work. The main lessons learned are detailed in Table 1. Soliciting residents’ motivations to build a sustainable organizational structure was key to maintaining resident participation. Recruiting and retaining diverse leaders who are open to trainee collaboration was also essential.

Table 1.

Lessons Learned. This Table Describes Our Main Recommendations for Successfully Designing and Implementing Health Justice Standards to Address Health Equity at the GME Level

| For trainees | For programs | For national GME bodies |

|---|---|---|

|

• Identify and articulate a mission and vision that resonate with diverse stakeholders, including peers, DOM leadership, and patients • Develop a cohesive and sustainable organizational structure • Utilize rotating leadership structures to mitigate schedule-driven lulls in productivity • Develop a long-term plan, but identify opportunities for incremental change |

• Recruit and work to retain diverse leadership with DEI and advocacy expertise • Flatten the hierarchy—be willing to learn from trainees and students • Provide FTE to a dedicated faculty member, selected by residents, to support resident-led advocacy initiatives • Allow and encourage trainees to use protected time for advocacy efforts |

• Demonstrate commitment to health equity by requiring residents to receive health-equity-related education commensurate with education on biological drivers of health • Incorporate health equity concepts into standardized testing, GME core competencies, entrustable professional activities, and milestone development |

It is significant that the Standards are presented on Emory’s website not as the framework of our resident advocacy group but of Emory IM. The framework was co-constructed, with residents driving the initiative and leadership suggesting modifications. This iterative process defined a set of shared values between leadership and trainees. This allowed us to focus on productive discussion of how to best achieve these goals, not whether they were important. Though this process inherently involves compromise, the result was a set of goals shared by leadership, who have the power to allocate resources towards actualizing them.

Emory leadership was also unique in being willing to build from a framework developed by junior colleagues. Rigorous approaches for making institutions more equitable already exist, but because many are developed by students, they are frequently overlooked by leadership. If more institutions became comfortable with inverting the hierarchy, progress could be expedited.

Through the Standards development, we identified several long-term goals but were also able to create rapid change. For example, after only a few meetings, the Emory IRB agreed to require that all researchers define race and its use in their study as part of the submission process, a decision with institution-wide impact.

Creation of the Standards also facilitated resident engagement in advocacy. Our survey demonstrates that residents are interested in health equity advocacy and believe this is their professional responsibility. This finding is consistent with a recent larger study of US medical students’ attitudes towards physician advocacy.11 The main barriers to resident involvement in advocacy in our program were identified as time and knowledge about how to contribute. However, after providing a detailed, transparent plan for improving health equity at Emory IM, discussing active projects, and framing this within our shared vision, we saw a statistically significant increase in the number of residents who were now ready to participate in advocacy.

Every fall, we review and revise these Standards. First, we move accomplished work from Planned Actions to Current Status. Second, we identify Planned Actions for the upcoming year to move us closer to achieving each Standard. Third, we evaluate the Standards themselves and modify as needed. We then submit the updated Standards to leadership for review and posting on Emory’s website.

The most significant limitation of our work is the insular, academic nature of this first Standards iteration. In spring 2020, when this effort began, there were many barriers to making local connections—the shutdown of community meetings and our increased workloads as IM residents during the pandemic the most significant. We decided to move forward with our starting framework while working on building community connections in parallel with the plan to increasingly involve community stakeholders in our annual Standards reviews. We have since made strong connections with a coalition of local decarceration-focused activists in Atlanta (Communities Over Cages, which is led by Women on the Rise, a group of formerly incarcerated women). We plan to request their input on the next round of Standards revisions, particularly Standard 12, which focuses on protecting the rights of incarcerated patients. We are also working on inviting community organizers and other stakeholders to give some of the Health Justice Curriculum talks as expert guest lecturers. As we continue to build these relationships, we will continue to request feedback on the Standards. Because the Standards is a living, annually revised document, we can incorporate broader perspectives and improve our framework.

The quantitative results of this paper must be interpreted with limitations. Although we presented at a required noon conference, residents are sometimes unable to attend or are paged out of conference due to patient care issues, and residents on electives and outpatient months are also not required to attend. Thus, we did not receive survey responses from every Emory IM resident.

Barriers remain to maximal implementation of this framework. We have demonstrated that residents want to get involved but lack adequate time for robust participation in advocacy. As is typical for DEI efforts, most of the people undertaking this uncompensated labor are women and people of color who are already heavily engaged similar volunteer work on other fronts. If time were protected for advocacy the way it is for research, this work could progress more quickly.

Our medical systems are the result of intentional policies, many of which have been created by, and therefore must be dismantled by, physicians. If we believe that achieving health equity is a priority, we must approach this work with the same urgency as we do when addressing biological drivers of disease. Our process provides a template for others to implement similar frameworks in their institutions. Eventually, joining these institutional approaches into a national framework would allow us to maintain momentum for continuously improving health equity despite ebbs and flows in professional energy,12 decrease overreliance on individuals by motivating systemic change, and help translate enthusiasm into concrete improvements rather than performative statements.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Contributors: We would like to acknowledge the numerous medical student groups, including White Coats for Black Lives and The Student National Medical Association, whose health equity frameworks and proposals formed the foundation of our Standards. We would also like to thank Dr. Karen Law, Dr. Kimberly Manning, Dr. Jada Bussey-Jones, The Emory DEI Council, and the leaders and members of the Churchwell Diversity and Inclusion Collective for their contributions to these Health Justice Standards. Finally, thank you to our Emory Internal Medicine coresidents for participating in our survey.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press (US), Copyright 2002 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.: Washington (DC); 2003. [PubMed]

- 2.ACGME statement on medical education racial discrimination allegations. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Newsroom; 2021.

- 3.Nasca TJ. A Message from Dr. Thomas J. Nasca. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Newsroom; 2021.

- 4.Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. The American Association of Medical Colleges Diversity in Medicine: Facts and [cited December 17, 2022]; Available from: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018#:~:text=Diversity%20in%20Medicine%3A%20Facts%20and%20Figures%202019,-New%20section&text=Among%20active%20physicians%2C%2056.2%25%20identified,as%20Black%20or%20African%20American.

- 5.Lett E, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: A longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE 2018;13(11):e0207274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ly DP. Historical Trends in the Representativeness and Incomes of Black Physicians, 1900-2018. J Gen Intern Med 2021;7(5):1310-1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Berkowitz SA, Cené CW, Chatterjee A. Covid-19 and Health Equity — Time to Think Big. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(12):e76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bobo KA, et al. Organizing for social change: Midwest Academy manual for activists. Fourth edition. ed. Santa Ana, CA: The Forum Press. x; 2010. 401 pages.

- 9.Racial Justice Report Card. White Coats for Black Lives; 2021 [cited June 5, 2022]: Available from: https://whitecoats4blacklives.org/rjrc/.

- 10.The J. Willis Hurst Internal Medicine Residency Health Justice Standards. 2022 [cited June 5, 2022]; Available from: https://med.emory.edu/departments/medicine/_documents/health-justice-standards-report.pdf.

- 11.Chimonas S, et al. The future of physician advocacy: a survey of U.S. medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Manning KD. A reckoning of racial reckoning. Lancet 2022;399(10327):784-785. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.