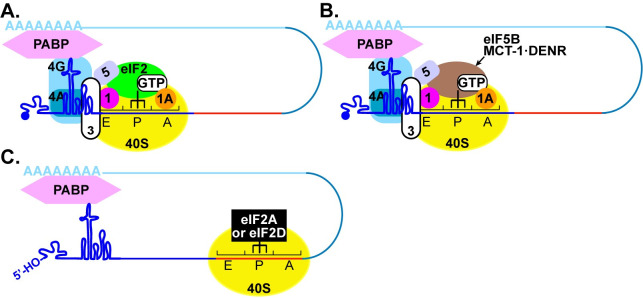

Fig 14. Models for initiation of translation on the enterovirus genome.

(A) Under normal conditions, eIF4G and eIF4A bind to the primary IRES and recruit the 43S preinitiation complex composed of the 40S ribosomal subunit (yellow), eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNAiMet (green), and eIF3, among other factors. Initiation may also be facilitated by interactions of the poly(rA)-binding protein, PABP, bound to the 3′-poly(rA) tail. This interaction may use eIF4G or viral/cellular factors interacting with the cloverleaf. Translation begins at the AUG start site in an eIF2-directed manner. (B) Multiple distinct eIF2-independent mechanisms exist. Both eIF5B and MCT-1•DENR (brown) can substitute for eIF2 to promote recruitment of initiator tRNA and translation initiation at the AUG start site. These factors may also initiate at non-AUG codons. (C) A canonical IRES-independent, eIF2A/eIF2D-dependent mechanism. Activation of intrinsic antiviral defense mechanisms, for example, as a result of the presence of the 5′-OH as a component of structured RNA in our biosynthetic enteroviral genomes, will lead to inactivation of eIF2 and perhaps even sequestration of eIF3. The noncanonical translation initiation factors eIF2A and eIF2D (black) direct translation initiation from a region of RNA (red) within 2A-coding sequence in a manner that is not dependent on the presence of an AUG codon but may require cis-acting RNA element upstream of the site of translation initiation as suggested by the studies reported herein. Other than the 40S ribosomal subunit, factors leading to formation of the translation–initiation complex are not known.