Abstract

Cervical teratoma is a rare form of teratoma in neonates and is an unusual cause of cervical masses in them. Teratomas are unusual tumors derived from all 3 germs cell layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm, with varying proportions. The cervical teratoma is a rare entity. Its prognosis mostly depends on the risk of neonatal respiratory distress, its extension and potential malignancy. Surgical management must be as complete as possible to avoid recurrences and malignant transformation. We report a case of a cervical immature teratoma in an infant with total excision and cure. No recurrence has been reported. The aim of our study is to review the diagnosis, management and outcomes of congenital cervical teratomas. Cervical teratoma although uncommon should be considered in the differential diagnosis of neck masses in neonates. Teratomas are rare tumors derived from all three germ cell layers affecting the neck in 3% of all cases. An early complete surgical approach to congenital cervical teratomas allows good results with low rates of complication and recurrence.

Keywords: Teratomas, Infant, Congenital, Surgical treatment

Introduction

Teratomas are malformed tumors comprising of ectodermal, endodermal and mesodermal tissues which are derived from the transformation of nests of multipotent germ cells [1]. Therefore their histological profile is heterogenous and includes cystic or solid areas along with mature or immature components. Dermoids however are derived from only ectoderm and mesoderm. About 2.3%–9.3% of all paediatric teratomas are cervical teratomas. The first reported case of a cervical teratoma was made by Hess in 1854. The incidence is reported to be between 1 in 20,000 and 1 in 40,000 live births. They are peculiar compared with other teratomas in that there is no female preponderance [2].

Cervical teratomas are generally unilateral and arise from the anterolateral part of the neck. They have well-defined margins and are multiloculated. Cervical teratomas can compress the oropharyngeal pathway and impair fetal swallowing which leads to development of poyhydramnios. It is seen in 30% of the affected population. Polyhydramnios can lead to preterm labor. They can present postnatally with respiratory distress and a progressive swelling leading to facial disfigurement. They may also cause significant hyperextension of the child’s neck. The tumor also prevents lungs from expanding and developing properly, causing pulmonary hypoplasia which can lead to severe hypoxia [3]. Giant cervical teratomas may even cause fetal hydrops. Teratomas may also be associated with cardiovascular compromise. There may be rupture of teratoma which might result in contamination of the airway. This may be complicated by adverse surgical sequelae. Few cases may have asymptomatic gradual enlargement. Rapid growth is often indicative of secondary infection or inflammation. There is an 18% risk of accompanying congenital malformations [4].

Cervical teratomas is often confused with other differentials of a neck mass especially lymphangioma, hemangioma, cervical congenital thyroid goiter, branchial cyst, cervical neuroblastoma and soft tissue sarcoma. The diagnosis of teratoma can be made via routine antenatal ultrasound scans in the second trimester of pregnancy featuring hydramnios and a cervical mass with calcifications. Antenatal diagnosis is the rule in US but may not be the case in developing countries as was in our case. CT scan and MRI can provide important clues for diagnosis. Cervical ultrasound and CT scan show cystic or heterogeneous mass with both solid and liquid components along with calcifications. MRI helps in distinguishing the different types of tissues, lesion limits and the possible mass effect on the adjacent structures [1].

Abnormal levels of tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein and β-HCG (beta human chorionic gonadotropin) should make one suspicious about the possibility of malignant component in the teratoma. Teratoma is histologically classified as mature and immature. The mature teratoma is benign and represents 95% of cases [2]. The histologic picture of benign teratoma is diverse and shows presence of squamous epithelium, gastrointestinal epithelium and smooth muscle components. Few times, cervical teratomas involve the thyroid gland. Rapid enlargement could result in airway obstruction, despite its absence initially. Therefore immediate and complete resection is the mainstay treatment, even if there is no upper airway obstruction at the time of presentation [5].

Case Report

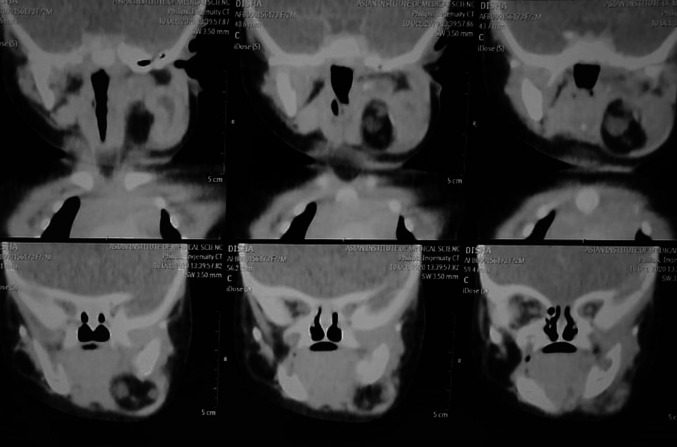

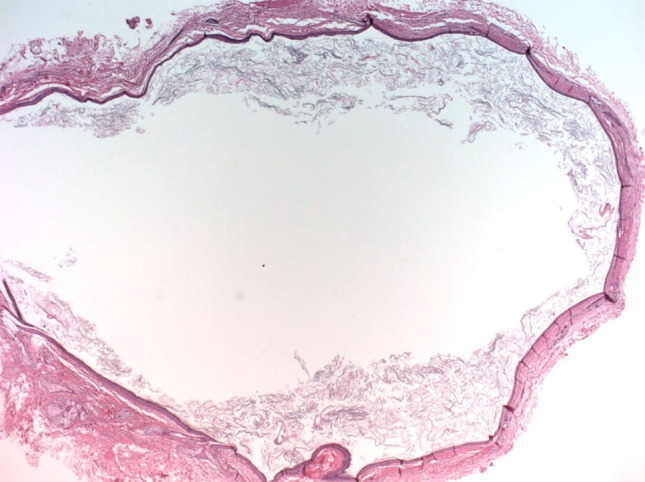

A 2 month old female child presented to the ENT OPD with complaints of a progressively increasing left sided neck swelling since birth. The mother also complained of the child having difficulty in feeding for the last 10 days. There was no history of breathing difficulty, noisy breathing or cyanosis. Rest of the history was unremarkable. On examination, there was a globular, cystic, mobile, non-tender mass measuring 5 × 5 cm with well-defined margins observed in the left submandibular region. The overlying skin was normal. (Fig. 1) Intra oral examination showed presence of left buccal mucosa bulge. Contrast enhanced Computed Tomography showed a well-defined lesion showing fat density, a few calcified foci along with heterogeneously enhancing components in the left submandibular region measuring 5 × 4.1 × 3.1, suggestive of teratoma. (Fig. 2) Pre-operative FNAC was suggestive of a lipomatous lesion. The patient was planned for excision of the mass under general anaesthesia. Intraoperative findings included a well capsulated mass extending up to the floor of the mouth. All the vital neurovascular structures were preserved and the mass was removed in toto along with the ipsilateral submandibular gland. Grossly it was 4 × 4.5 × 3 cm size encapsulated solid mass with a pale yellow bosselated surface possibly extending into the submandibular gland. (Fig. 3) Microscopic examination of the specimen showed features of mature cystic teratoma. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph of the patient pre-operatively & post-operatively

Fig. 2.

CECT neck showing multiple calcified areas mixed with cystic spaces

Fig. 3.

Excised specimen (4 × 4.5 × 3 cm)

Fig. 4.

Microphotograph showing mature cystic teratoma

Discussion

Cervical teratomas are rare congenital tumors with a mortality of 80–100% if not managed and resected immediately. The increased mortality in head and neck teratomas is because of upper airway obstruction or oropharyngeal obstruction due to local mass effect. Stillbirth frequency of 17% and a 35% incidence of upper airway obtstruction has been seen in children presenting with cervical teratoma. Such patients need to be fed and nursed in a certain position preoperatively to minimize these risks. The location and size of the tumor are thus more important than the grade for predicting a favourable outcome [5].

The risk of malignancy in congenital cervical teratomas is less than 5%. The risk of malignancy is more if the age at presentation is more. Children presenting with cervical teratoma in the first decade mostly have benign disease but the tumor is locally aggressive. The risk of of malignancy also depends upon the grade of maturity of the component tissues which is classified using the Gonzalez-Crussi grading system: 0 or mature (benign); 1 or immature, probably benign; 2 or immature, possibly malignant (cancerous); and 3 or frankly malignant. The most prevalent are the dermoids, which even though are benign, have unlimited growth potential [6].

Antenatally, most cervical teratomas can be diagnosed on ultrasound scans which show mixed echogenicity and acoustic shadowing. It shows a multiloculated solid-cystic mass with calcifications. Calcifications are seen in 50% of cervical teratomas. Polyhydramnios can also be appreciated in 20% of these tumours. CT is used to assess the size and extent of these lesions. Most teratomas have fat, which is an important diagnostic imaging hallmark to distinguish these tumors from lymphatic malformations. MRI can help distinguish among various tissue types without exposing neonates to radiation. The differential diagnosis for a cervical mass in neonates includes lymphatic malformation, hemangioma, brachial cleft cysts, lipoma and laryngocele [7].

Definitive management of these tumours is surgical excision. A foetus diagnosed with a large cervical teratoma is sometimes managed by C-section with EXIT (ex-utero intra partum technique) procedure or OOPS (operation placenta support). Tumor excision in infancy, as was done in our case, should be completed expeditiously to tackle the threat of respiratory impairment and to prevent sepsis, ulceration, hemodynamic instability and coagulopathy. Complete tumor excision also eliminates the risk of malignant degeneration in the future. The surgery however has an operative mortality of 15%. Possible post-operative complications include damage to the recurrent laryngeal, hypoglossal and marginal mandibular nerves [3].

There is disruption of normal cervico-facial development due to stretching of nerve fibers which leads to dysfunction of facial structures, neck musculature and cranial nerve. This increases the risk of post-operative cranial nerve dysfunction, like problems with speech and eating. Some may require tracheostomy and gastrostomy tubes. Skin breakdown and wound infection may also occur. Airway support may be necessary postoperatively, even in cases with no pre-operative airway difficulties because of laryngotracheomalacia, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage and post intubation edema. These changes tend to be temporary and reverse following resolution of edema. Because of close proximity of the thyroid gland and frequent involvement, thyroid profile and calcium homeostasis should also be checked pre and post-operatively [8].

Follow-up is done by comparing the pre-and post-operative levels of tumors markers. After surgical excision, AFP levels should be checked at birth, at 1 month, after every 3 months in infancy and yearly thereafter, till 3 years. It is advisable to get MRI scanning biannually for the first 3 years of life. This is done because there is an increased risk of recurrence, malignant transformation and metastasis to regional lymph nodes. Recurrence can occur in less than 10% after surgery. In cases of recurrent extracranial immature teratomas, treatment with combination of chemotherapy following surgical excision showed a favourable tumor-free survival rate of 98.6% [7]. If there is malignant transformation of a previously benign teratoma, management in the form of multi-agent chemotherapy along with complete excision can be offered. There is no evidence that radiation is beneficial, also it is potentially harmful for the child. Drop in the values of serial alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) measurements to normal levels assures a complete resection after cessation of the chemotherapy. Long term sequelae of cervical teratoma include increased risk for development of hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, developmental delay and mental retardation [9]. There should be a multi-disciplinary involvement for the management of a cervical teratoma which should be continued from neonatal period until growth has finished.

Prognosis depends upon several factors like degree of maturity of tissues and completeness of resection. Others include airway obstruction at birth and associated anomalies. The risk of mortality in benign teratomas by infection, compression of important structures, and operative complications are particularly more in low body-weight patients. Therefore the best way to go about treating a cervical teratoma is prompt diagnosis and expeditious excision to avoid immediate complication like respiratory compromise and delayed problems like recurrence and malignant conversion [8].

Authors’ Contributions

SM and PN made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the manuscript, data collection, and manuscript writing. PS gave final approval of the manuscript version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval is not applicable. Consent to participate was obtained from the parents of the patient.

Consent for Publication

Written and informed consent to publish this information was obtained from the parent of the study participant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sonali Malhotra, Email: sonalimalhotra@hotmail.com.

Prerna Negi, Email: prerna.negi16@gmail.com.

Poonam Sagar, Email: poonamsgr.mamc@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Issa Koné F, Hajjij A, Cissé N, et al. Congenital cervical teratoma. Surg Sci. 2019;10:44–48. doi: 10.4236/ss.2019.101006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gundry SR, Wesley JR, Klein MD, et al. Cervical teratomas in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:382–386. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(83)80186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivares E, Castellow J, Khan J, et al. Massive fetal cervical teratoma managed with the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. Radiology Case Reports. 2018;13:389–391. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolter NE, Siegele B, Cunningham MJ. Cystic cervical teratoma: a diagnostic and management challenge. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;95:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, O’Donoghue MJ, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Tumors and tumorlike lesions of the testis: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22:189–216. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.1.g02ja14189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakravarti A, Shashidhar TB, Naglot S, et al. Head and neck teratomas in children: a case series. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0224-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang J, Park J. Huge congenital cervical immature teratoma mimicking lymphatic malformation in a 7-day-old male neonate. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:16–18. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2016.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shine NP, Sader C, Gollow I, et al. Congenital cervical teratomas: diagnostic, management and postoperative variability. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2006;33:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shetty KJ, Prasad HLK, Rai S, et al. Unusual presentation of immature teratoma of the neck: a rare case report. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:647. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.137994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]