Abstract

In fat myringoplasty, fat harvested from ear lobule is used as graft material for the closure of small size central perforation of tympanic membrane under local anaesthesia. This study was performed over a period of 5 years (January 2016–December 2020) on 67 cases who underwent surgery and were willing to participate in the study at our tertiary hospital. Closure of perforation was found in 93% of cases within 2–3 months of surgery. Hearing gain was 6.8 dB on an average and morbidity was insignificant in successful cases. Fat myringoplasty is a successful yet simple procedure for repair of small size perforations. It is a day-care procedure under local anaesthesia requiring minimal tissue handling. It is also cost effective and has minimum post-operative morbidity. The likely cause of failure are ear infections and graft displacement due to respiratory tract infections. Results of the fat myringoplasty also depend upon the experience of the operating surgeon and cooperation of the patient.

Keywords: Small central perforation, Fat myringoplasty, Chronic suppurative otitis media, Day care procedure

Introduction

A lot of patients seek ENT consultation for central perforation of tympanic membrane on daily basis around the world. A significant number of these cases are often found having very small central perforation. Fat myringoplasty is a very simple procedure that can be performed under local anaesthesia to close such small perforations using ear lobule fat. Fat myringoplasty is an alternative by which we can avoid tympanoplasty where tissue handling and morbidity is definitely more. This being a day care procedure has good compliance with patients eligible for this.

Aims and Objectives

To calculate the rate of successful closure of tympanic membrane (TM) perforation.

To measure the amount of hearing gain in successful cases.

Study the improvement of subjective sufferings after fat myringoplasty.

Methods

All cases of our study were collected from outpatient department of the department of otorhinolayngology (ENT) at our tertiary hospital over a period of 5 years (January 2016–December 2020) who were willing to undergo surgery. This study was done on 67 cases. Detailed clinical history, results of local examination, general examinations and systematic examination were recorded in each case.

Inclusion Criteria

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) with tiny to small central perforation i.e. approximately ≤ 30% area of tympanic membrane (pars tensa).

No ear discharge for last 2 months.

No significant pathology in middle ear (tympanic) cavity as assessed clinically by otoscopy/otoendoscopy/microscopic examination.

Age group between 18 and 65 years having mild to moderate conductive hearing loss on pure tone audiometry with pneumatic or diploic mastoid on X-ray.

The causes of perforation in our cases were mostly post-inflammatory i.e. in 64 (96%) cases and post-traumatic in 3 (4%) cases.

All patients selected for the study were eligible according to the inclusion criteria. These patients were selected based upon clinical examination findings having tiny to small central perforation i.e. approximately ≤ 30% area of tympanic membrane (pars tensa) involved. Investigations done were routine blood investigations, X-ray mastoids, pure tone audiometry (both pre and post operatively), otoendoscopy/microscopic examination and diagnostic nasal endoscopy (to rule out nasal pathologies pre-operatively).

Surgical Steps

All surgeries were performed under standard antiseptic measures under local anaesthesia by injection of 5 ml of 2% lignocaine with adrenaline (1:80,000) in four quadrants of external ear canal and behind the ear lobule.

A small horizontal incision of about 1 cm was put on the skin behind the ear lobule. Adequate amount of fat was harvested from ear lobule depending upon the size of the perforation and preserved in normal saline. Margins of the perforation were de-epithealised (made raw) circumferentially. Care is taken to avoid any ossicular disruption during manipulation over the tympanic membrane. Piece of fat graft of suitable size was inserted through the perforation so that half portion goes inside middle ear and half portion remains outside the TM. The graft is kept so that it snugly fits in the perforation making a dumb-belle effect. Antibiotic soaked gelfoams were kept supporting the graft.

In post-operative period, patients were advised to avoid entry of water in the ear for atleast 4–6 weeks. They were prescribed with oral antibiotics, antihistaminics and anti-inflammatories for 3–4 weeks prophylactically. Patients were followed up regularly for at least for 3 months. In the first month–weekly, in the second and third month—biweekly follow ups were done. Post-operative pure tone audiometry was done at 6 weeks.

Results

Among the selected 67 cases, there was a female predominance seen–Females: 47 (70%) and Males: 20 (30%). Most of the patients were between 21–30 years of age–24 (38%) followed by > 20 years age group–17 (25%). There was no history of any previous surgeries before fat myringoplasty in 63 (94%) cases. The remaining 4(6%) patients were post-tympanoplasty with small persistent defect/perforation.

Most of the cases had mild conductive loss (26–40 dB) i.e. in 60 cases (89%) while rest 7 cases (11%) had moderate conductive hearing loss (Table 1). X-ray of mastoid (schuller’s view) showed pneumatic nature for most cases–53 (79%) while was diploic only in 14 cases (21%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Degree of hearing loss in cases

| Degree of hearing loss by PTA | No. of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Mild (26–40 dB) | 60 (89%) |

| Moderate (41–55 dB) | 7 (11%) |

| Total | 67 |

Table 2.

Degree of pneumatisation in cases

| Degree of pneumatisation (X-ray mastoid Schuller’s view) | No. of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Pneumatic (cellular) | 53 (79%) |

| Diploic | 14 (21%) |

| Total | 67 |

Patients were followed up for atleast 3 months post-operatively. In the first month–weekly, in the second and third month–biweekly follow ups were done. Post-operative pure tone audiometry was done at 6 weeks. The progress was followed up as stated in Fig. 1 above. One week post-operatively, fat grafts found to be in situ in 54 cases (81%) while rest 13 cases (19%) showed displacement of fat grafts. All these cases were followed up with conservative medical management. Amongst these cases, in 8 cases (12%) the size of the perforation reduced and healed on conservative management, while in 5 cases (7%) the perforation remained persistent with or without increase in its size. These cases were categorized as failure cases that needed tympanoplasty later. As observed, ultimately perforation healed in 93% cases within 2–3 months.

Fig. 1.

Progression in cases as observed on follow-ups clinically

In our cases, the pre-operative mean air–bone gap was 22.4 dB while the post-operative mean air–bone gap was found 15.6 dB at 6 weeks. Hence the observed average hearing gain was 6.8 dB.

The subjective sufferings of the cases, both pre- and post-operatively are summarized in Table 3. Decreased hearing and ear discharge (recurrent) were in 96% and 80% of the cases respectively before fat myringoplasty being the most common complaints. Post-operatively decreased hearing (though improved comparatively) and ear discharge was seen in only 11% and 6% cases respectively. Hardness of hearing was persistent even post operatively even after successful closure of tympanic membrane perforation in cases. Stiffness of repaired tympanic membrane may be responsible for this hearing loss as no one suffered from deterioration on sensorineural hearing loss.

Table 3.

Complaints (symptoms)–comparison pre- and post-operatively

| Complaints (symptoms) | Pre-operative (%) | Post-operative (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ear discharge (recurrent) | 54 (80%) | 4 (6%) |

| Decreased hearing | 64 (96%) | 7 (11%) |

| Ear ache | 38 (56%) | 5 (8%) |

| Ringing sound or abnormal sound | 20 (30%) | 6 (9%) |

Morbidity following fat myringoplasty was nearly insignificant in cases with successful closure of tympanic membrane perforation. There was no pain after nearly a week of surgery. Healing of perforation was complete within 2–3 months in most of the cases (Figs. 2, 3).

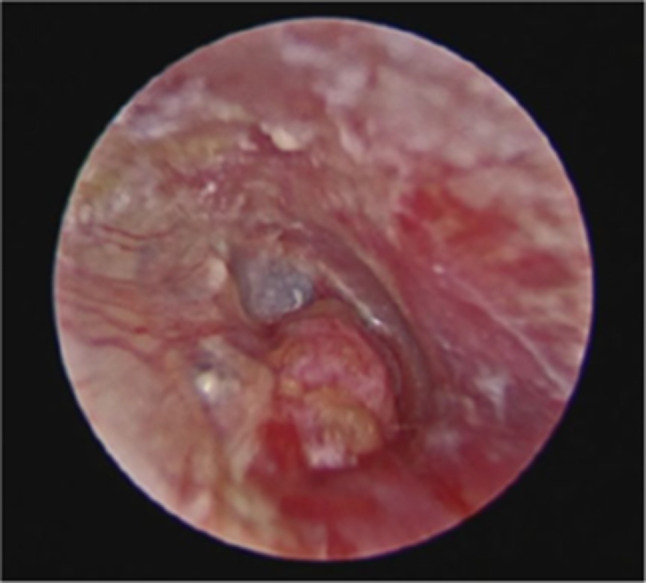

Fig. 2.

Fat graft (F) plugged through perforation

Fig. 3.

The fat graft was inserted through the perforation as an hourglass-shaped plug

Discussion

In our literature there are various management techniques mentioned for small size central perforations of tympanic membrane.

Making the margins raw mechanically using micro-ear instruments or alternatively by chemical cauterization using TCA (trichloroacetic acid) can promote healing. Derlacki et al. advocated a 90% success rate of closure of perforation after an average 3.7 treatments per patient (quickest closure by two treatments and longest by 64 treatments) [1]. In this method, repeated attendance by the patient is required which has low patient complaince. Fat myringoplasty is a single sitting day-care surgery. Hence, patient compliance is much better for our procedure. Success rate of conventional tympanoplasty for small (> 30% area involvement) central perforation is 97% in our setup and it is definitely better than fat myringoplasty. But the morbidity and the cost of therapy is much higher for tympanoplasty. Therefore, in selective cases this can be a preferable method.

In a similar study carried out by Hagemann and Hausler, they showed closure of perforation in 91% of cases and hearing gain of 5–10 dB [2]. In our study we have found the rate of successful closure being 93% and hearing gain of 6.8 dB on an average. The rate of closure was comparable with other similar studies carried out by Chalishazar et al. [3], Mitchl et al. [4], Roee Landsberg et al. [5], Emir et al. [6] and Caye-Thomsasen et al. [7] where the rate of successful closure of tympanic membrane were 90%, 92% and 81.6%, 85.7% and 94% respectively.

According to the study carried out by Roee Landsberg et al. they also showed a significant improvement in speech reception threshold (18.5 ± 7.7 dB vs. 23.5 ± 8 dB) which was comparable to the average hearing gain in our study (6.8 dB) [5]. Caye-Thomsasen et al. [7] and Brown et al. [8] in similar studies also showed a hearing gain of 8.6 dB and 9.33 dB (± 5.11) respectively.

In our study, fat graft was harvested from the ipsilateral ear lobule. Rao et al. did microscopic comparison of fat from 3 sources (ear lobule, abdomen and buttocks) which showed that fat cells from ear lobule were more compact and contains fibrous tissue [9]. Garem et al. in their study of FPM using different types of fat noted the success rate for ear lobule fat was 80% and for abdominal fat was 73.3% [10]. Harvesting the fat graft from the ipsilateral ear lobule also is convenient surgically as doesn’t require exploring another area of the patient’s body adding to surgeon’s and patient’s compliance both.

Complete healing of perforation was achieved within 2–3 months in most of the cases. Healing occurs by epithealisation over the scaffolding of fat graft whereas the fat graft itself takes longer time for complete resumption to occur. In 19% of cases repair of perforation were seen even after displacement of fat graft on first visit. This is because of denudation of margin of perforation while operating. Release of some tissue factor from the applied fat may have promoted growth of epithelium as well.

Graft failure may be due to infection, displaced graft or dehiscence due to undersized grafts. Fiorio and Barbieri described various causes of failure- Immediate failures due to technical difficulties such as anterior perforations, inadequate graft support, infection or poor vascular supply and delayed failures due to atrophic TM, infections or eustachian tube dysfunction with change in the TM structure [11]. Hegazy et al. described technical operative points during fat grafting that is, graft size in relation with the perforation, moistening of the lateral side of the graft and degree of lateral bulge in the fat plug as important factors for its success [12].

The most likely causes of failure in our study were infections in the ear despite the antibiotic coverage and respiratory tract infections producing cough and sneezing leading to graft displacement.

Conclusion

In our study, we were able to achieve a high success rate of 93% of repair of tympanic membrane perforation by fat myringoplasty. This is a day-care procedure under local anaesthesia requiring minimal surgical intervention. It is also cost effective and has minimum post-operative morbidity. Even though fat myringoplasty is a highly successful yet simple procedure for repair of small size perforations, it is an under-utilized procedure. We advocate practising it more often for the benefit of patients.

Even though it is an excellent procedure, it has its own limitations. Results of the fat myringoplasty also depend upon the experience of the operating surgeon and cooperation of the patient as it has to be performed in an awake patient under local anaesthesia. Other than the failure accounting due to infections and graft displacement due to RTI, these are certain pitfalls that too require attention.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Nil.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the institute.

Informed Consent

Informed consents were taken from all patients participating in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Derlacki EL. Repair of central perforations of tympanic membrane. AMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1953;58(4):405–20. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1953.00710040427003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagemann M, Häusler R. Tympanoplastik mit autologem Fettgewebe [Tympanoplasty with adipose tissue] Laryngorhinootologie. 2003;82(6):393–396. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalishazar U. Fat plug myringoplasty. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57(1):43–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02907626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell RB, Pereira KD, Lazar RH. Fat graft myringoplasty in children–a safe and successful day-stay procedure. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111(2):106–108. doi: 10.1017/s002221510013659x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roee Landsberg MD, Gadi Fishman MD, Ari DeRowe MD, Eli Berco MD, Gilead Berger MD. Fat graft myringoplasty: results of a long-term follow-up. J Otolaryngol. 2006;35(1):44–47. doi: 10.2310/7070.2005.4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emir H, Ceylan K, Kizilkaya Z, Gocmen H, Uzunkulaoglu H, Samim E. Success is a matter of experience: type 1 tympanoplasty: influencing factors on type 1 tympanoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(6):595–599. doi: 10.1007/s00405-006-0240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caye-Thomasen P, Nielsen TR, Tos M. Bilateral myringoplasty in chronic otitis media. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(5):903–906. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318038168a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown C, Yi Q, McCarty DJ, Briggs RJS. The success rate following myringoplasty at the royal victorian eye and ear hospital. Aust J Otolaryngol. 2002;5:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao SM, Chandra PR, Pallapati G, Pradeep KJ, Gudepu P. A comprehensive study of fat myringoplasty. ORL. 2015;5(1):8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Garem HF. Fat myringoplasty: better patient selection for better results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(1 suppl):206–207. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiorino F, Barbieri F. Fat graft myringoplasty after unsuccessful tympanic membrane repair. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(10):1125–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegazy H. Fat graft myringoplasty–a prospective clinical study. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2013;14:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejenta.2012.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]