Abstract

Tolosa Hunt syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by idiopathic chronic granulomatous lesion involving cavernous sinus. The presenting symptoms are severe frontal headache, periorbital pain, ptosis, and diplopia. Usually, patients with headache and ptosis primarily visit neurologists or ophthalmologists. Only when imaging reveals any intracranial lesion involving paranasal sinuses, these patients get referred to otorhinolaryngologists. We would like to describe here the challenges we faced as otorhinolaryngologist, in diagnosis and management of a case of painful ophthalmoplegia as Tolosa Hunt Syndrome. A 55-year-old male presented to us with complaints of left frontal headache, periorbital pain, diplopia, and ptosis of left eye. Imaging and endoscopic biopsy revealed granulomatous lesion involving cavernous sinus with no evidence of fungal aetiology. Patient responded well to systemic steroid therapy with complete resolution of symptoms and no remission till two years of follow up. Tolosa Hunt Syndrome remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Trans-nasal endoscopic biopsy in selected cases may be contributory to the diagnosis. It responds well to systemic steroid therapy. Although chances of relapse are there yet prognosis is excellent.

Keywords: Tolosa Hunt syndrome, Cavernous sinus, Headache, Ophthalmoplegia, Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Tolosa Hunt syndrome is characterized by recurrent frontal headache, severe periorbital pain and painful ophthalmoplegia caused by granulomatous inflammation involving cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure, orbital apex and sphenoid sinus [1]. The aetiology of this disease is still unknown. It shows excellent response to corticosteroid therapy. Primary diagnostic modalities are either contrast enhanced MRI revealing granulomatous lesion in cavernous sinus or biopsy from granulations involving sphenoid sinus.

Patients with headache and periorbital pain usually present to neurologist from where they are referred to otolaryngologist when imaging reveals any sinus pathology. For otolaryngologist the primary differential diagnosis in these types of cases is chronic inflammatory sinusitis or chronic fungal sinusitis. Tolosa Hunt syndrome remains largely a diagnosis of exclusion. We would like to report a case of headache with painful ophthalmoplegia which was diagnosed as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome after an extensive battery of investigations and was treated successfully.

Case Report

A 55-year-old male referred to us from neurology department with complaints of left frontal headache and left periorbital pain for three weeks and diplopia with ptosis of left eye for one week. Headache was not associated with nausea, vomiting or photophobia. He had similar history of left frontal headache six month back which improved spontaneously, over a period of two weeks. He was a non-smoker and didn’t consume alcohol or any drugs. He had no comorbidities and other clinical history was unremarkable. On examination, he was afebrile, blood pressure and pulse rate were normal. On cranial nerve examination, there was ptosis of left eye (Fig. 1a) with restricted ocular movements in all directions. Ocular movements in right eye were normal in all directions. Visual acuity and pupillary light reflex were found to be within normal limits. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy didn’t reveal any significant abnormality.

Fig. 1.

Eye changes during treatment. a ptosis of left eye at presentation, b partial improvement of ptosis 72 h after steroid therapy, c complete improvement after 3 weeks

Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C- reactive protein, angiotensin converting enzyme level and thyroid profile were within normal limit.

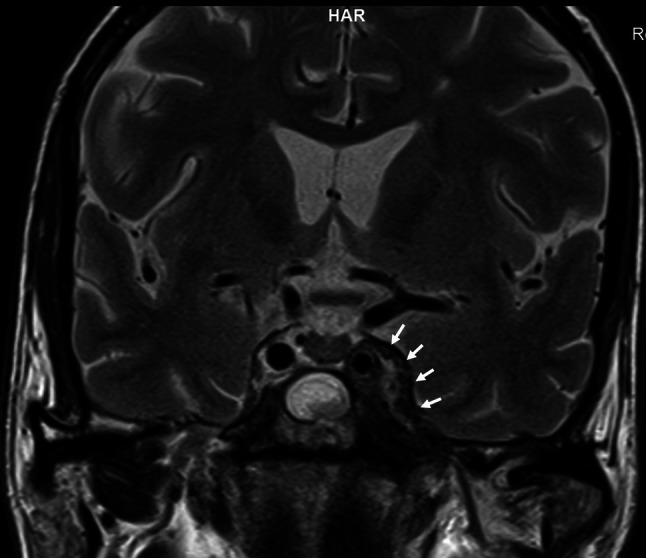

Contrast enhanced MRI of brain revealed 3.4 × 4.0 × 2.0 cm heterogeneous enhancing soft tissue lesion involving bilateral cavernous sinuses encasing internal carotid artery on both the sides. The lesion was extending to bilateral superior orbital fissures and pituitary fossa, displacing the pituitary gland towards right. Posteriorly, the lesion was extending from posterior clinoid process to base of clivus with subtle bony erosion in posterior wall of sinus and adjacent clivus. There was erosion of anterior wall of left sphenoid sinus with involvement of left posterior ethmoidal air cells. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

MRI brain showing granulomatous lesion of left cavernous sinus (denoted by white arrows)

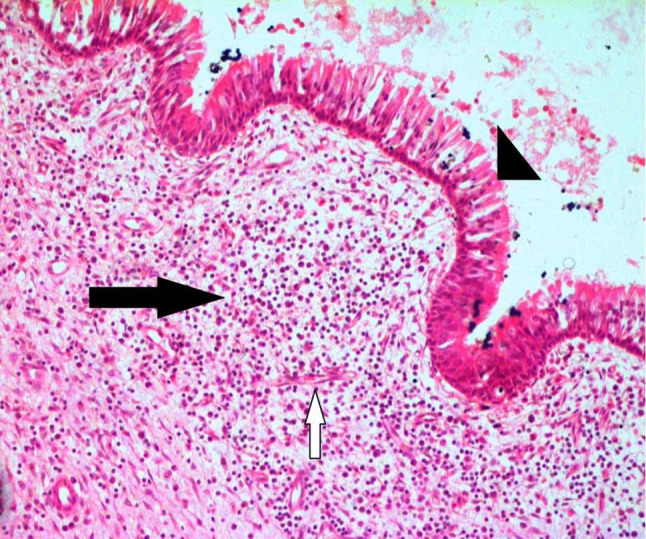

Initial working diagnosis of invasive fungal sinusitis was made, and patient was planned for endoscopic biopsy from left sphenoid sinus. Endoscopic examination revealed pulsatile polypoidal mucosa in left sphenoid sinus from which multiple punch biopsy were taken and sent for KOH mount, fungal culture, and histopathological examination. KOH mount and fungal culture didn’t reveal any fungal elements. Histopathology revealed subepithelial tissue showing mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, foreign body giant cells and few neutrophils along with congested blood vessels, in a myxoid and oedematous stroma. (Fig. 3) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative for any fungal organism.

Fig. 3.

Pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium (arrowhead) mucosal lining of sphenoid sinus with underlying sub epithelium showing inflammatory infiltrate (black arrow) with proliferating small thin-walled blood vessels (white arrow) in an oedematous stroma. (H&E × 10)

Based on the findings of above investigations, a provisional diagnosis of Tolosa hunt syndrome was made and injection methyl prednisolone was initiated at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight. After 48 h patient reported significant reduction in pain around left eye and ptosis improved partially after 72 h of steroid therapy (Fig. 1b). Injectable methyl prednisolone was continued till seven days after which patient was shifted to oral prednisolone with a tapering regimen for four weeks. Due to financial constraints patient was unable to do a follow up MRI. After four weeks, ptosis, diplopia and headache did improve completely (Fig. 1c). Patient is doing fine till two years of follow up without any remission.

Discussion

Tolosa Hunt Syndrome (THS) is a rare cause of painful ophthalmoplegia characterized by idiopathic nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammation of cavernous sinus that responds well to steroids. This case report emphasizes the role of appropriate test battery to rule out all other causes of painful ophthalmoplegia before arriving at the diagnosis of THS.

It was first described by Eduardo Tolosa in 1954 in a 47-year-old man with severe left-sided orbital pain and total ophthalmoplegia in whom autopsy subsequently revealed granulomatous inflammation in cavernous sinus [2, 3]. A few years later in 1961 Hunt et al. reported a similar clinical entity in six patients that responded well to steroid therapy [2, 3].

Till now, the aetiology of this syndrome is unknown, and it has been reported in all age groups with no sex predilection [4]. The incidence of THS is estimated to be 1 to 2 cases per million [4].

The onset of THS is usually acute and symptoms last for one or more weeks. Initial presenting symptoms are frontal headache and ipsilateral periorbital pain that recurs and remits over weeks followed by paralysis of extra ocular muscles leading to ptosis and diplopia. THS usually affects cranial nerves IIIrd, IVth and VIth. Involvement of ophthalmic division of Vth nerve, optic, VIIth and VIIIth nerves have also been reported [5].

Differential diagnoses of THS are invasive fungal sinusitis, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, giant cell arteritis, orbital pseudo tumour and basal meningitis.

Extensive battery of investigation is warranted to exclude all possible causes of painful ophthalmoplegia including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C- reactive protein, angiotensin converting enzyme level (sarcoidosis), c ANCA (vasculitis) and thyroid profile. Contrast enhanced CT scan of brain may reveal soft tissue density in cavernous sinus but is less sensitive than MRI.

Diagnostic modality of choice for THS is contrast enhanced MRI (following sequential protocol of T1 weighted, turbo-T2, FLAIR and T1 weighted with contrast) [6].

MRI is non-invasive and it accurately detects granulomatous lesion in 92.1% of THS patients [7]. Dynamic MRI has been reported to be better than conventional MRI in detecting granulomatous lesion [8].

Contrast agents such as gadolinium, thallium-201 and gallium-67 citrate all have been reported to have utility in delineating granulomatous lesion [9, 10]. It should be kept in mind that MRI may reveal normal findings in small number of patients with THS. As the lesion is located in cavernous sinus, biopsy is technically difficult and dangerous. But when the lesion is involving sphenoid sinus endoscopic biopsy can be performed for confirmation of diagnosis. Histopathological picture is usually consistent with features of chronic granulomatous lesion.

In 2018, 3rd edition of International Classification of Headache Disorders has defined the diagnostic criteria for THS as follows–

-

A.

Unilateral orbital or periorbital headache fulfilling criterion C

-

B.Both of the following:

- Granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit, demonstrated by MRI or biopsy

- Paresis of one or more of the ipsilateral IIIrd, IVth and/or VIth cranial nerves

-

C.Evidence of causation demonstrated by both of the following:

- Headache is ipsilateral to the granulomatous inflammation

- Headache has preceded paresis of the IIIrd, IVth and/or VIth nerves by 2 weeks, or developed with it

-

D.

Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis [5].

Mainstay of treatment of THS is corticosteroid therapy. There is no clear guideline or protocol regarding dose and duration of corticosteroid therapy. In most of the existing reports, intravenous methylprednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg at tapering regimen has shown excellent improvement in symptoms. Periorbital pain and cranial nerve paresis usually improve within 72 h of steroid therapy. At discharge, patient can be shifted to oral methyl prednisolone to be continued for at least 4–6 months. Adverse effects of steroid therapy include cushingoid habitus, hyperglycaemia, peripheral oedema, peptic ulcer and glaucoma. Some cases of THS may relapse during tapering or after completion of steroid therapy. In these steroid resistant cases Infliximab (tumour necrosis factor α inhibitor) has shown promising results [11]. It is administered intravenously at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg per infusion [11]. In future gamma knife radiosurgery may be an alternative in steroid resistant cases [12].

Conclusion

Patients with painful ophthalmoplegia and radiological findings in para nasal sinus are often referred to otorhinolaryngologists. They must be carefully evaluated for all other serious causes of ophthalmoplegia before arriving at a diagnosis of THS. Investigation of choice for THS is contrast enhanced MRI but findings are not pathognomonic. We suggest supplementing the test battery with endoscopic biopsy from accessible lesion for an early and reliable diagnosis. Corticosteroid therapy remains the mainstay of management. Minority of cases may show relapse following steroid therapy, but overall prognosis is excellent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tsirigotaki M, Ntoulios G, Lioumpas M, Voutoufianakis S, Vorgia P. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: clinical manifestations in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;99:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine P, Brown J, Moster M, Kenning J, Ronis M. The Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: a case report. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 1990;102(4):402–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989010200415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lueck C. Time to retire the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome? Pract Neurol. 2018;18(5):350–351. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachanas V, Karatzias G, Tsitiridis I, Panaras I, Sandris V. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome misdiagnosed as sinusitis complication. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(1):97–99. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106005317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):177. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.La Mantia L, Curone M, Rapoport AM, Bussone G, International Headache Society Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: critical literature review based on IHS 2004 criteria. Cephalalgia. 2004;26(7):772–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ZečevićPenić S, Lisak M, Gregurić T, Hećimović H, Bašić KV. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome—case report. Acta Clin Croat. 2017;56(2):331–337. doi: 10.20471/acc.2017.56.02.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akpinar ÇK, Özbenli T, Doğru H, Incesu L. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome - Cranial Neuroimaging Findings. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2017;54(3):251–254. doi: 10.5152/npa.2016.13791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sánchez Vallejo R, Lopez-Rueda A, Olarte AM, San RL. MRI findings in Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (THS) BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014206629. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206629.PMID:25368129;PMCID:PMC4225287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakisaka Y, Kobayashi T, Uematsu M, Numata Y, Hirose M, Hino-Fukuyo N, Tsuchiya S, Doi H, Fukuda H, Kure S. Utility of thallium-201 scintigraphy in Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229(1):83–6. doi: 10.1620/tjem.229.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halabi T, Sawaya R. Successful treatment of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome after a single infusion of infliximab. J Clin Neurol. 2018;14(1):126–127. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2018.14.1.126.PMID:29629550;PMCID:PMC5765250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemeny AA. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome: another legitimate target for radiosurgery? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016;158(1):141. doi: 10.1007/s00701-015-2649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]