Abstract

Background:

Comparative studies of the naturalistic course of patients of opioid dependence on naltrexone and buprenorphine are likely to be helpful for clinical decision-making. The article aimed to report on the three-months naturalistic outcomes of patients discharged on naltrexone or buprenorphine from the same center.

Methods:

Patients with opioid dependence who were discharged on either naltrexone (n = 86) or buprenorphine (n = 30) were followed up for three months for retention in treatment. The patients were also followed up telephonically, and the Maudsley Addiction Profile was applied.

Results:

The days of retention in treatment were significantly higher in the buprenorphine group (69.5 versus 48.7 days, P = 0.009). Heroin use, pharmaceutical opioid use, injection drug use, involvement in illegal activity, and percentage of contact days in conflict with friends in the last 30 days reduced over three months in both the groups, while the physical and psychological quality of life improved in both the groups. Additionally, in the naltrexone group, smoked tobacco use, cannabis use, and percentage of contact days in conflict with family within the last 30 days reduced at three months compared to baseline.

Conclusion:

With the possible limitations of choice of medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence being determined by the patient, and prescribing related factors and sample size constraints, the study suggests that retention outcomes may vary between naltrexone and buprenorphine, though both medications may improve several patient-related parameters. However, a true head-to-head comparison of the outcomes of buprenorphine and naltrexone in a naturalistic setting may be difficult.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Naltrexone, Outcomes, Longitudinal, Addictive disorders

Key Messages:

1. After inpatient treatment for opioid dependence, retention may be higher for buprenorphine than for naltrexone.

2. There is a reduction in illicit opioid use and a decrease in illegal activities with the use of either buprenorphine or naltrexone.

Medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence syndrome (ODS) has shown promising benefits. Improved outcomes have been found with medications for the treatment of ODS in terms of reducing the number of days of illicit opioid use, along with improvement in personal and social functioning. Medication- assisted treatment for ODS comprised primarily of two approaches: opioid agonist treatment (in the form of methadone or buprenorphine) or opioid antagonist treatment (naltrexone). These approaches have different mechanisms of action. While opioid agonists reduce the withdrawal symptoms and craving for opioid use, naltrexone prevents the re-initiation of opioid use after a period of abstinence by blocking the hedonistic effects of opioids. Meta-analyses of efficacy trials of these medications have been conducted. Buprenorphine in adequate doses is associated with less frequent opioid use and reduction in mortality.1, 2 Similarly, naltrexone is associated with reduced opioid use. 3

Naltrexone and buprenorphine are fundamentally different approaches to treatment; while one emphasizes abstinence as a prerequisite and promotes an opioid-free lifestyle, the other aims to reduce the drive to take illicit opioids and to control the craving and withdrawals with medications. Many factors influence the choice of medications that are offered to patients and accepted by them, including availability, funding mechanisms, coercion of mandated treatment, patient’s own preconceptions, and therapist proclivities.4–7 Many centers provide both buprenorphine and naltrexone to patients with ODS. 8 However, comparison of these two medication approaches has been done mainly in randomized controlled trials.9, 10 Randomized controlled trials, however, assume that the propensity to choose either of the approaches would be similar, while that might not be so in the actual clinical situation. Comparative outcomes in naturalistic outpatient clinical outcomes are likely to be helpful for clinicians treating patients with ODS to inform the types and outcomes of patients treated with these medications. Thus, we aimed to assess the three-month naturalistic outcomes of patients discharged on naltrexone or buprenorphine after admission to the same addiction treatment facility.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This prospective three-month naturalistic follow-up study was done at a public-funded addiction treatment facility in India that is affiliated with a medical school. The facility provides outpatient and inpatient care to patients with substance use disorders, and the care is provided by a team of psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, social workers, and nursing personnel. Treatment is subsidized, and the clientele largely comprises individuals from lower socioeconomic strata. ODS and alcohol dependence syndrome are the most common substance use disorders for which clients seek treatment at the center. Inpatient treatment is mostly geared toward short-term (within two weeks) detoxification, and the center has about 800 admissions annually.

The decision for medication-assisted treatment for ODS at the center is based on collaborative decision-making involving the treating team, patient, and family members. Naltrexone is started after a negative naloxone challenge test three to four days after completion of buprenorphine-based detoxification. A daily oral dose of 50 mg naltrexone per day is prescribed at discharge, with a suggestion to the family members to supervise the treatment when possible. Patients are prescribed naltrexone for a period of about a week or two at discharge, with subsequent prescription refills of up to a month. Those who are more suitable for opioid substitution treatment (individuals with a long duration of opioid use, injecting drug use, or multiple failed treatment attempts) are given buprenorphine in single sublingual optimized doses. The patients are then discharged on sublingual buprenorphine to be dispensed daily from the center or from another opioid substitution treatment facility (with take-home dispensing initially given in some instances). Based upon the completion of two to three months of daily dispensing of buprenorphine, take-home doses for up to a week are considered for patients based upon the attainment of treatment goals and availability of supervision of treatment at home. Both the medications (buprenorphine and naltrexone) are provided free of cost to the patients from the center. Clinicians conduct follow-ups and enquire into the current use of substances and engagement into work, though rating scales are not used for documenting the current status. In case a patient drops out of treatment, in the usual clinical scenario, efforts are not made to contact the patient for treatment re-engagement.

The inclusion criteria for the present study included male sex, diagnosis of ODS as per the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines, age of ≥ 18 years, and willingness to provide contact details, including a valid telephone number, for follow-up. Only male participants were included to homogenize the sample, as women comprise less than 2% of the admitted patients in the center. 11 Those who did not consent to participate in the study, were unwilling for telephonic calls and interviews, or had unplanned discharges (leave against medical advice, transfer out because of medical conditions, or referral to another center for treatment) were excluded.

Procedure

The study was started after the approval of the Institute Ethics Committee. Inpatients fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were approached for participation. Data collection was done by one of the investigators (VV) from 2018 to 2019. Sociodemographic and substance-use-related details were obtained. Participants were assessed on Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) for baseline data. This instrument was developed by Marsden et al. 12 for the purpose of treatment outcome research in addiction. It is a brief, structured interview and measures problems in four domains, that is substance use, health risk behavior, physical and psychological health, and personal/social functioning. Each item is scored separately in numbers and/or percentages. It was adapted for the use in this study by adding natural opioids and prescription opioids. Stimulants and illicit methadone, which are not frequently being used in the region, were clubbed as “others”. The list of crime events was modified to include selling drugs, stealing from home, stealing from outside/robbery, fights in public, assault, and pickpocketing. The items were translated to Hindi by using the translation and back translation technique.

The participants’ records were checked every month for the next three months after the discharge to note retention in treatment. Patients were considered as retained if they followed up within seven days of the scheduled follow-up date. Information was gathered from the records also about hospitalization duration, treatment at discharge, and duration of retention in treatment. At three months, all participants were contacted on the phone for telephonic interviews (up to five attempts were made on different days of the week and at different times, till a maximum of four weeks of the scheduled telephonic follow-up). Outcome at three months was assessed using items from the MAP.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the sociodemographic characteristics, reasons to leave treatment, and drug-use-related information. Survival analysis was done for retention in treatment, and the results were interpreted by the Kaplan-Meier estimated probabilities and log-rank test for the two medications— and naltrexone. The group differences between those who were retained and those who dropped out from the study, for demographic and drug use variables, were analyzed by using appropriate parametric (paired-sample t-test/independent sample t-test) or nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank test/Mann–Whitney U test) for quantitative variables and Chi-square/Mc-Nemar’s test for categorical variables. The level of statistical significance was kept at P = 0.05 for all tests. Missing value imputation was not done. Data analysis was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

Results

Of the 163 admissions during the period, 156 patients were approached for inclusion (seven were not approached). Of them, twenty-three had unplanned discharges, ten were not planned for treatment from the center (i.e., they were referred for treatment elsewhere), two did not provide a valid phone number, and one did not give consent. Hence, 120 patients were recruited for the study. At discharge, 86 received naltrexone, 30 received buprenorphine, and 4 did not receive any opioid agonist or antagonist. The present analysis compares patients on buprenorphine and naltrexone. Those in the buprenorphine group were of greater age, had lower per capita income, were more likely to have an additional psychiatric disorder, and were more likely to have received treatment with buprenorphine in the past (Table 1). The characteristics of the patients on the MAP are shown in Table 2. The two groups had similar number of days of different opioid use, number of days of use of other substances, physical and psychological health scores, rates of injecting drug use, and rates of involvement in illegal activities. However, the percentage of days in a conflict in the 30 days prior to admission was higher in the naltrexone group. The median dose of buprenorphine at discharge was 12 mg per day (range 2 mg to 26 mg per day), while naltrexone was prescribed in a uniform dose of 50 mg per day.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Information (n = 116)

| Variable | Buprenorphine Group (n = 30) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

Naltrexone Group (n = 86) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

Comparison (P Value) |

| Age | 34.3 (± 12.1) | 29.3 (± 9.6) | t = 2.25 (0.026)* |

| Male sex | 30 (100%) | 86 (100%) | c2 = 0.00 (1.000) |

| Currently married | 16 (53.3%) | 47 (54.7%) | c2 = 0.02 (0.901) |

| Formally educated | 27 (90.0%) | 75 (87.2%) | c2 = 0.16 (0.686) |

| Currently employed/ student | 20 (66.7%) | 61 (70.9%) | c2 = 0.19 (0.661) |

| Hindu religion | 19 (63.3%) | 66 (76.7%) | c2 = 2.04 (0.153) |

| Living in joint family | 11 (36.7%) | 37 (43.0%) | c2 = 0.37 (0.543) |

| Distance from the center in km | 113.8 (± 138.3) | 129.9 (± 167.1) | U = 1106.5 (0.242) |

| Per-capita monthly income in Indian rupees | 5095 (± 5538) | 8677 (± 9922) | U = 985.5 (0.037)* |

| Presence of additional psychiatric disorder | 6 (20.0%) | 5 (5.8%) | c2 = 5.22 (0.022)* |

| Duration of opioid use in years | 9.5 (± 8.1) | 8.4 (± 6.3) | t = 0.76 (0.447) |

| Duration of current admission in days | 18.3 (± 12.5) | 16.1 (± 6.5) | t = 1.26 (0.209) |

| Previously ever admitted for opioid dependence | 14 (46.7%) | 39 (45.3%) | c2 = 0.03 (0.901) |

| Previously received medical treatment for opioid

dependence Naltrexone Buprenorphine |

19 (73.1%) 7 (26.9%) |

53 (94.6%) 3 (5.4%) |

c2 = 7.71 (0.005)* FE P = 0.010* |

FE: Fisher’s Exact Test, SD: Standard Deviation: * significant at P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Addiction and Health Characteristics at Baseline (n = 116)

| Variable | Buprenorphine Group (n = 30) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

Naltrexone Group (n = 86) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

Comparison (P Value) |

| Number of days of use in last 30 days | |||

| Heroin (n = 96) | 22.4 (± 11.1) | 23.5 (± 10.5) | t = 0.39 (0.695) |

| Any pharmaceutical opioid (n = 43) | 23.9 (± 11.2) | 21.3 (± 11.1) | t = 0.72 (0.477) |

| Natural opioids (n = 4) | 10.7 (± 1.2) | 10 (–) | U = 1.00 (0.530) |

| Injection drug use (n = 27) | 18.2 (± 14.6) | 21.5 (± 11.4) | t = 0.65 (0.519) |

| Other substance use in the last 30 days | |||

| Smoked tobacco (n = 99) | 30.0 (± 0.0) | 29.6 (± 3.4) | U = 875.00 (0.552) |

| Smokeless tobacco (n = 57) | 30.0 (± 0.0) | 28.0 (± 6.1) | U = 247.00 (0.202) |

| Cannabis (n = 62) | 20.3 (± 12.6) | 19.3 (± 12.4) | U = 334.50 (0.956) |

| Alcohol (n = 58) | 6.3 (± 8.1) | 10.0 (± 11.5) | U = 110.50 (0.342) |

| Benzodiazepines (n = 15) | 18.0 (± 15.0) | 22.9 (± 13.2) | U = 24.00 (0.581) |

| MAP general health score | 15.9 (± 8.6) | 13.0 (± 6.8) | t = 1.83 (0.069) |

| MAP psychological health score | 17.7 (± 9.4) | 14.9 (± 9.2) | t = 1.42 (0.160) |

| Whether engaged in illegal activities in last 30 days | 13 (43.3%) | 28 (32.6%) | c2 = 1.13 (0.288) |

| Social functioning in last 30 days | |||

| Partner–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 84) | 11.6 (± 25.2) | 15.3 (± 29.9) | U = 566.50 (0.700) |

| Family–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 120) | 10.7 (± 22.5) | 27.3 (± 37.3) | U = 971.00 (0.037)* |

| Friends–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 104) | 8.9 (± 19.0) | 10.6 (± 21.0) | U = 871.50 (0.547) |

Notes: MAP: Maudsley Addiction Profile, SD: Standard Deviation, not all patients reported being in contact with partners/friends, * significant at P < 0.05.

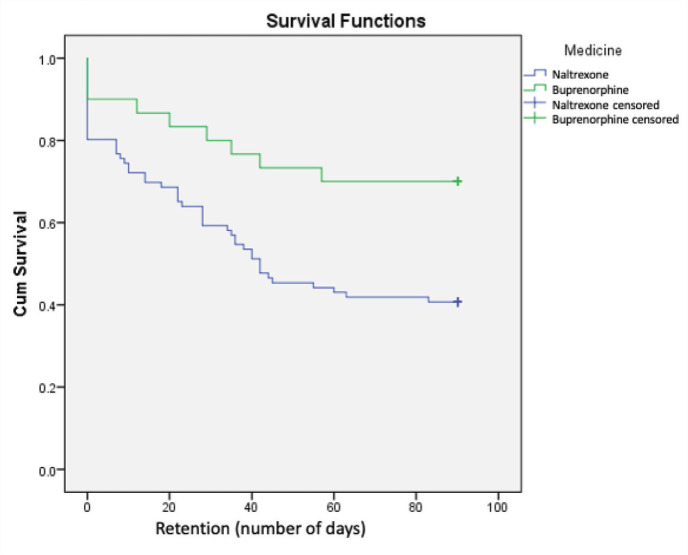

The survival analysis of the groups is shown in Figure 1. The days of retention in treatment were significantly higher in the buprenorphine group (69.5 versus 48.7, Log Rank Mantel-Cox Chi-square 6.848, P = 0.009). The median (interquartile range) of the days of retention, with a cap of 90 days, for the buprenorphine and naltrexone groups were 90 days (42 days to 90 days) and 42 days (9 days to 90 days), respectively.

Figure 1. Retention of Patients of Buprenorphine or Naltrexone in Treatment.

Information about outcomes at three months was obtained from 91 out of 116 participants (24 out of 30 patients in the buprenorphine group and 67 out of 86 patients in the naltrexone group). The baseline data and three-month outcomes are shown in Table 3. Heroin use, pharmaceutical opioid use, injection drug use, involvement in illegal activity, and percentage of contact days in conflict with friends in the last 30 days reduced in both the groups, while physical and psychological quality of life improved in both the groups. Additionally, in the naltrexone group, smoked tobacco use, cannabis use, and percentage of contact days in conflict with family within the last 30 days reduced.

Table 3.

Outcomes of Buprenorphine and Naltrexone Groups at Three Months Follow-up (n = 91)

| Variable | Buprenorphine Group (n = 24) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

Naltrexone Group (n = 67) Mean (± SD)/n(%) |

||

| Baseline | Three Months | Baseline | Three Months | |

| Whether used in the last 30 days | ||||

| Heroin | 16 (66.7%) | 3 (12.5%)* | 56 (83.6%) | 19 (28.4%)* |

| Any pharmaceutical opioid | 13 (54.2%) | 2 (8.3%)* | 22 (32.8%) | 8 (11.9%)* |

| Natural opioids | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Injection drug use | 9 (37.5%) | 0 (0.0%)* | 9 (13.4%) | 2 (3.0%)* |

| Whether other substance use in the last 30 days | ||||

| Smoked tobacco | 20 (83.3%) | 15 (62.5%) | 56 (83.6%) | 45 (67.2%)* |

| Smokeless tobacco | 10 (41.7%) | 9 (37.5%) | 36 (53.7%) | 35 (52.2%) |

| Cannabis | 11 (45.8%) | 9 (37.5%) | 37 (55.2%) | 23 (34.3%)* |

| Alcohol | 10 (41.7%) | 7 (29.2%) | 22 (32.8%) | 27 (40.3%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 6 (25.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | 7 (10.4%) | 2 (3.0%) |

| MAP general health score | 16.2 (8.5) | 11.8 (6.9)* | 12.9 (6.8) | 8.5 (5.7)* |

| MAP psychological health score | 2.8 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.1)* | 2.1 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.3)* |

| Whether engaged in illegal activities in last 30 days | 10 (41.7%) | 1 (4.2%)* | 21 (31.3%) | 5 (7.5%)* |

| Social functioning in last 30 days | ||||

| Partner–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 84) | 13.8 (28.0) | 10.7 (26.3) | 15.5 (29.7) | 10.0 (25.4) |

| Family–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 120) | 12.9 (24.8) | 7.4 (21.0) | 26.0 (37.1) | 6.3 (19.3)* |

| Friends–percentage of contact days in conflict (n = 104) | 11.2 (20.8) | 0.4 (1.1)* | 6.5 (12.9) | 5.4 (21.2)* |

Note: MAP: Maudsley Addiction Profile, SD: Standard Deviation Not all patients reported being in contact with partners/friends, * difference significant between baseline and 3 months at P < 0.05 (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test/Paired T-Test/Mc-Nemar Test).

Discussion

The present study suggests that more patients on buprenorphine were retained in treatment than those on naltrexone. The retention was similar to the findings of Mokri et al. 10 but lower than the rates reported by Lee et al. 9 Both these studies were randomized trials, and being a part of a trial might have influenced the retention rates to some extent. Bandawar et al. 13 had also reported that the odds of retention in treatment were higher among those who were on buprenorphine than naltrexone.

The retention rate of patients on buprenorphine was 66.7%, which is comparable to other studies. Liebschutz et al. 14 reported a retention rate of 63.3% in Boston for a group of hospitalized patients who were started on buprenorphine prior to their discharge and linked to office-based buprenorphine treatment. Ruger et al. 15 reported retention of 63.6 % in a study from Malaysia, a country with a similar socioeconomic background. A systematic review that looked into retention in low- and middle-income countries reported a retention rate of 74.5%. 16 However, the retention rates at three months have also been reported to be as low as 33.8% in a study from India. 17

We found the retention rates of patients on naltrexone to be 41.9%, which is comparable to those found by researchers from the United States, Australia, and India, who found the rates to be 44.4%, 43.8%, and 41%, respectively.18–20 A few older studies have also found better retention on naltrexone than the present study. The retention rate was around 70% in a study on federal probationers in the United States 21 and 77% among a sample of opioid-dependent patients detoxified in a hospital in Spain. 22 On the contrary, Capone et al. found a retention rate of 32% on naltrexone for patients in a US county. 23 Preston et al. 24 noted that at three months, their patients on naltrexone who were not on any contingency had retention between 5% and 20% compared to 50% in the contingency group. In the present study, an a priori willingness to come for more frequent dispensing in the buprenorphine group might have contributed to better retention rates when compared to naltrexone.

Among the patients who could be contacted at three months, heroin use, any pharmaceutical opioid use, and injection drug use had significantly declined in both the groups, though the decrement was more pronounced in the buprenorphine group. This suggests that both these treatment options have favorable outcomes. Improvement was also seen in physical and psychological health. This was similar to other literature that has suggested an improvement in health- related quality of life and mental health with buprenorphine.25, 26 Involvement in criminal activities also decreased with either of the medications. Additionally, conflicts with the family significantly decreased in the naltrexone group but not the buprenorphine group, possibly because of the power differential offered to the family members by the act of home supervision of this medication. Conflicts with friends also decreased with either of the medications, but the decrement was substantially more in the buprenorphine group. This could be ascribed to a lesser need to engage with the friends with an intent to arrange for money and share the substances. There was some, but an unremarkable, decrease in the use of other substances with either of the medications.

Demographic characteristics of the participants with a mean age of about 31 years, the majority being married, educated till secondary level, employed, from nuclear family, and from low incomes, is consonant with other studies on substance use from similar treatment facilities.18, 27–30 Studies from other countries also report similar profiles, except for more participants being employed in our sample.31–33 Comorbid illness in less than a quarter of participants is also similar to another study from India, but a family history of substance use was reported more in that study. 27 The average opioid use duration of around nine years is similar to a previous study involving similar patients; 28 however, it differed from another study by the same authors from the same center because that included a specific age group. 16 Heroin, which is locally called “smack,” has been used by a majority of the patients—a finding similar to other studies from India and abroad.17, 28, 33, 34 It was followed by pharmaceutical opioids and natural opioids in that order, thus representing the use pattern at the national scenario as found in a recent national survey in India. 35

In the baseline characteristics of the sample, the patients in the buprenorphine group were likely to be older (but did not have a greater number of years of opioid use), had lower incomes, were more likely to have another diagnosed psychiatric illness, and were more likely to have been tried buprenorphine in the past. Possibly, the choice of buprenorphine as a treatment option was considered more frequently for those for whom it had been seen to work in the past. Though present only in a minority of the patients, an additional psychiatric disorder was again a consideration that possibly favored buprenorphine, as the presence of discomforting withdrawal symptoms or dysphoria in some individuals on naltrexone may have nudged the clinical decision toward buprenorphine. Moreover, the buprenorphine group had a lower mean income (per-capita less than US$100 per month), suggesting that perhaps those who were not earning currently, and hence having lower incomes, were able to commit to coming for daily dispensing to the clinic. However, this needs further clarity in future studies.

Interestingly, the distance from the center did not differ between the groups. The buprenorphine group was less likely to have a conflict with the family, suggesting that family conflicts were more likely to be associated with naltrexone as the choice of medication. It is possible that family pressures and expectancies, as experienced in the form of conflict prior to admission, lingered in the decision-making of medication choice, which requires further evaluation. The previous literature does hint toward family having a role in initiating treatment and choosing particular medications.36, 37

Our findings imply that three-month retention rates may be higher for patients with ODS prescribed buprenorphine. Careful consideration of choices, taking into account the logistics and patient preference, is important to decide upon the course of action to be followed in an individual case. Nonetheless, either of these medications is associated with a substantial decrement in the use of illicit opioids. Additionally, the use of these medications being associated with improved physical and mental health outcomes suggests that incremental health benefits accrued with treatment. Patients with ODS also seem to have other substance use, which probably need attention in their own right. A reduction in criminal behavior with either of these agents suggests that several indirect social benefits could occur with medication-assisted treatment.

Some limitations of the study should be considered while drawing inferences. The decision to start naltrexone or buprenorphine is generally based upon the collaborative discussion between the patient and the treatment team, with due consideration of logistic issues like the need for daily dispensing. Thus, the design is of clinical-scenario-based naturalistic follow-up rather than of randomized controlled trial, leading to potential selection biases for the two options. Additionally, we did not record or control for additional psychological interventions or any other adjunctive treatments that could have influenced the outcomes. Not all participants could be contacted at three months to ascertain the outcomes. The sample comprised exclusively of males and was recruited from a single center, so generalization should be made with caution. The buprenorphine dose varied widely from 2 mg per day to 26 mg per day, and the lower doses might not have been optimal in some patients. The study duration was only three months, and a longer duration of follow-up might have been better. Finally, we did not validate the adapted MAP.

Conclusion

Patients with ODS have greater rates of retention when treated with buprenorphine as compared to naltrexone. Decrement in illicit opioid use occurs with either buprenorphine or naltrexone. Future studies may look at the factors influencing the selection of medication-assisted treatment for ODS. A true head-to-head comparison of outcomes of buprenorphine and naltrexone in a naturalistic setting may be difficult. Studies may also look at the issues faced in supervision and the mechanisms of resolving those when family members are supervising oral naltrexone.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014; (2): CD002207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ, 2017; 357: j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larney S, Gowing L, Mattick RP, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of naltrexone implants for the treatment of opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev, 2014; 33(2): 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling W. A Perspective on opioid pharmacotherapy: Where we are and how we got here. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 2016; 11(3): 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koehl JL, Zimmerman DE, and Bridgeman PJ. Medications for management of opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm, 2019; 76(15): 1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe D and Saucier R. Biotechnologies and the future of opioid addiction treatments. Int J Drug Policy, 2020; 88: 103041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash S and Balhara Y.. Perceptions related to pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence among individuals seeking treatment at a tertiary care center in northern India: A descriptive study. Subst Use Misuse, 2016; 51(7): 861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huhn AS, Hobelmann JG, Strickland JC, et al. Differences in availability and use of medications for opioid use disorder in residential treatment settings in the United States. JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3(2): e1920843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CS, Liebschutz JM, Anderson BJ, et al. Hospitalized opioid-dependent patients: Exploring predictors of buprenorphine treatment entry and retention after discharge: Predictors of buprenorphine treatment entry and retention. Am J Addict, 2017; 26(7): 667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokri A, Chawarski MC, Taherinakhost H, et al. Medical treatments for opioid use disorder in Iran: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of buprenorphine/naloxone and naltrexone maintenance treatment. Addiction, 2016; 111(5): 874–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar S, Balhara YPS, Gautam N, et al. A retrospective chart review of treatment completers versus noncompleters among in-patients at a tertiary care drug dependence treatment centre in India. Indian J Psychol Med, 2016; 38(4): 296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marsden J, Gossop M, Stewart D, et al. The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): A brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome. Addiction, 1998; 93(12): 1857–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandawar M, Kandasamy A, Chand P, et al. Adherence to buprenorphine maintenance treatment in opioid dependence syndrome: A case control study. Indian J Psychol Med, 2015; 37(3): 330–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med, 2014; 174(8): 1369–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruger JP, Chawarski M, Mazlan M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of buprenorphine and naltrexone treatments for heroin dependence in Malaysia. PLoS One, 2012; 7(12): e50673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feelemyer J, Jarlais DD, Arasteh K, et al. Retention of participants in medication-assisted programs in low- and middle-income countries: An international systematic review. Addiction, 2014; 109(1): 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dayal P and Balhara YPS. A naturalistic study of predictors of retention in treatment among emerging adults entering first buprenorphine maintenance treatment for opioid use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2017; 80: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayal P, Balhara YPS, and Mishra AK. An open label naturalistic study of predictors of retention and compliance to naltrexone maintenance treatment among patients with opioid dependence. J Subst Use, 2016; 21(3): 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foy A, Sadler C, and Taylor A.. An open trial of naltrexone for opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev, 1998; 17(2): 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunes EV, Rothenberg JL, Sullivan MA, et al. Behavioral therapy to augment oral naltrexone for opioid dependence: A ceiling on effectiveness?. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 2006; 32(4): 503–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornish JW, Metzger D, Woody GE, et al. Naltrexone pharmacotherapy for opioid dependent federal probationers. J Subst Abuse Treat, 1997; 14(6): 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutiérrez M, Ballesteros J, González-Oliveros R, et al. Retention rates in two naltrexone programmes for heroin addicts in Vitoria, Spain. Eur Psychiatry, 1995; 10(4): 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capone T, Brahen L, Condren R, et al. Retention and outcome in a narcotic antagonist treatment program. J Clin Psychol, 1986; 42(5): 825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preston KL, Silverman K, Umbricht A, et al. Improvement in naltrexone treatment compliance with contingency management. Drug Alcohol Depend, 1999; 54(2): 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, Schwartz RP, et al. Changes in quality of life following buprenorphine treatment: Relationship with treatment retention and illicit opioid use. J Psychoactive Drugs, 2015; 47(2): 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raisch DW, Campbell HM, Garnand DA, et al. Health-related quality of life changes associated with buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. Qual Life Res, 2012; 21(7): 1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majumder P, Sarkar S, Gupta R, et al. Predictors of retention in treatment in a tertiary care de-addiction center. Indian J Psychiatry, 2016; 58(1): 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalana H, Kundal T, Gupta V, et al. Predictors of relapse after inpatient opioid detoxification during 1-year follow-up. J Addict, 2016; 2016: 7620860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh SM, Mattoo SK, Dutt A, et al. Long-term outcome of inpatients with substance use disorders: A study from North India. Indian J Psychiatry, 2010; 50(4): 269–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhat BA, Dar SA, and Hussain A. Sociodemographic profile, pattern of opioid use, and clinical profile in patients with opioid use disorders attending the de addiction center of a tertiary care hospital in North India. Indian J Soc psychiatry, 2019; 35: 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein ZM, Kim HW, Cheng DM, et al. Long-term retention in office based opioid treatment with buprenorphine. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2017; 74: 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magura S, Nwakeze PC, and Demsky SY. Pre- and in-treatm ent predictors of retention in m ethadone treatm ent using survival analysis. Addiction, 1998; 93(1): 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soyka M, Zingg C, Koller G, et al. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: Results from a randomized study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2008; 11(5): 641–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saxon AJ, Hser Y, Woody G, et al. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction: Methadone and buprenorphine. J Food Drug Anal, 2013; 21(4): S69–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, et al. Magnitude of substance use in India 2019. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Randall-Kosich O, Andraka-Christou B, Totaram R, et al. Comparing reasons for starting and stopping methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone treatment among a sample of white individuals with opioid use disorder. J Addict Med, 2020; 14(4): e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner V, Bertrand K, Flores-Aranda J, et al. Initiation of addiction treatment and access to services: Young adults’ accounts of their help-seeking experiences. Qual Health Res, 2017; 27(11): 1614–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]