Abstract

This systematic review consists of two parts. Part I seeks to synthesise evidence from primary or secondary research studies examining the implementation and effectiveness of case management tools and approaches currently being used to counter radicalisation to violence. Part II is an ‘overview of reviews’ that seeks to identify relevant and transferable lessons from systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of case management tools and approaches used in the broader field of violence prevention that could be applied to counter‐radicalisation practice.

1. BACKGROUND

This review seeks to identify key lessons for researchers, policymakers and practitioners working on the problem of radicalisation to violence by examining the effectiveness of case management tools and approaches being used in this space. It aims to go further than standard Campbell systematic reviews of intervention effectiveness by incorporating two distinct parts. Part I aligns with a standard Campbell systematic review procedure by examining case management tools and approaches that are used to counter the specific problem of radicalisation to violence. Part II goes further by examining case management tools and approaches that are used to counter other forms of interpersonal and collective violence, and discussing how evidence drawn from this research might inform interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence. By examining research that would fall outside the scope of a review solely focused on the problem of radicalisation to violence, Part II aims to capture insights relevant to policy, practice and research that would otherwise be absent.

1.1. The problem

1.1.1. Radicalisation to violence

Since the start of the 21st Century, the concept of ‘radicalisation’ has been used by policy‐makers and academics to refer to a variety of different phenomena, including the adoption of radical beliefs (both violent and non‐violent), as well as engagement in violent extremist and terrorist activity (Neumann, 2013). This review focuses on radicalisation to violence, defined as the process by which ‘a person or group takes on extreme ideas and begins to think they should use violence to support or advance their ideas or beliefs’ (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 7). The term ‘radicalisation’ is therefore used in this review to refer to the process by which individuals become engaged in or supportive of violent extremism, which is defined here as ‘the beliefs and actions of people who support or use violence to achieve extreme ideological, religious or political goals’ (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 7). Research examining broader forms of radicalisation (i.e., the adoption of non‐violent ‘radical’ or ‘extreme’ beliefs) is not included in this review on the basis that holding such beliefs is ‘not always illegal or necessarily problematic in and of itself’ (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 7; also Schmid, 2014).

Radicalisation is a contested concept, with some authors challenging the empirical evidence on which dominant models of radicalisation are based (e.g., Githens‐Mazer & Lambert, 2010; Kundnani, 2012). However, the term is now ubiquitous within counter‐terrorism policy circles around the world, and academic research into radicalisation has grown exponentially (Heath‐Kelly et al., 2015; Silva, 2018). This research has shown that there is no single process of radicalisation, nor a common profile of individuals who become radicalised (Horgan, 2008). Instead, individual trajectories into (and out of) violent extremism are shaped by a complex intersection between different ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors specific to individuals and/or the contexts in which they live (Lewis & Marsden, 2021; Vergani et al., 2020; Wolfowicz et al., 2020). Interventions working with clients who are considered to be ‘at‐risk’ of radicalisation and/or those who are already involved in violent extremism must therefore be responsive to the specific and varied characteristics, circumstances and needs of each individual (Cherney, 2021; Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020; Gielen, 2018; Koehler, 2017).

Interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence are increasingly drawing on case management approaches to deliver this type of individually tailored work to clients (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Case management interventions, broadly defined as programmes that work with individual clients by tailoring intervention plans to each client's specific needs, have long been used to deliver client‐focused interventions in a range of other policy areas, including healthcare, social work and corrections (Lukersmith et al., 2016). Importantly, interventions incorporating a case management component have been effective in countering individual involvement in different forms of violence (e.g., Brantingham et al., 2021; Engel et al., 2013), including ideologically‐motivated violence (Weine et al., 2021). This evidence of effectiveness, coupled with research pointing to the individualised nature of radicalisation, would suggest that using case management models to deliver counter‐radicalisation work is theoretically sound, provided that the tools and approaches used are effective (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020; Koehler, 2017). However, there is a lack of clarity around the types of case management tools and approaches that are being used to counter radicalisation to violence, and their impact remains unclear.

Previous reviews have illustrated that the evidence base underpinning counter‐radicalisation interventions, including those using case management tools and approaches, is weak (Bellasio et al., 2018; Feddes & Gallucci, 2015; Pistone et al., 2019). Existing systematic reviews of programme evaluations have illustrated the paucity of studies that would meet the inclusion criteria for a standard Campbell systematic review (e.g., Pistone et al., 2019; van Hemert et al., 2014). This is, in part, because of the significant methodological and conceptual challenges facing efforts to evaluate these interventions (Baruch et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2020). A particular challenge relates to identifying appropriate client‐level outcome measures or indicators. These are not always explicit and can vary according to the specific objectives of the intervention in question (Cherney et al., 2018), and across different clients (Gielen, 2018).

More fundamentally, no study has yet sought to systematically identify and assess the tools and approaches used in case management counter‐radicalisation interventions and understand how these are used in practice. Existing research has tended to focus on individual aspects of a case management process, with a heavy emphasis on risk assessment (Scarcella et al., 2016), and efforts to interpret outcomes (Cherney & Belton, 2020). Similarly, although a small number of studies have explored how case managed counter‐radicalisation interventions are being implemented (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Weeks, 2018), there has been no systematic research that looks across the different stages of the case management process in the field of countering radicalisation to violence, and limited comparative work mapping the ways that different tools and approaches are used in practice.

Part I of this review sets out to address these key gaps in research on counter‐radicalisation. Part II aims to go further than a standard Campbell systematic review by analysing case management tools and approaches that are not specifically designed to tackle the problem of radicalisation to violence, but which might produce relevant lessons to work in this space.

1.1.2. The relationship between violent extremism and other forms of violence

Violent extremism is a particular phenomenon that has characteristics that distinguish it from other forms of violence. However, it is now increasingly recognised that lessons from interventions seeking to tackle other forms of violence, such as gang‐related violence or larger‐scale militancy, could be applied to interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence (e.g., Baruch et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2017; Ris & Ernstorfer, 2017). Although less well‐established, there is also a growing interest in exploring how interventions working with convicted sex offenders and violent offenders might be applied to counter‐radicalisation research and practice (e.g., Cherney et al., 2021). Such lessons are likely to be particularly relevant for those seeking to design, use and evaluate case management tools and approaches in the field of counter‐radicalisation. This is because, as noted above, case management has long been used to prevent individuals from participating in other forms of targeted violence, and to tackle recidivism among violent offenders. In turn, a number of systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of case management tools and approaches in countering violent offending (e.g., Viljoen et al., 2018). However, there has yet to be any systematic analysis of the transferability of these tools and approaches to efforts at countering radicalisation to violence. Part II of this review will seek to address this gap.

1.2. The intervention

Parts I and II of the review examine interventions from different fields. However, whilst these interventions seek to tackle different phenomena, namely radicalisation to violence (Part I) and other forms of targeted violence (Part II), there are links between them. This section therefore discusses both types of intervention in turn, as well as the synergies between them.

1.2.1. Defining ‘radicalisation to violence’

Despite the term's ubiquity today, there remains a lack of consensus over how to define ‘radicalisation’, or how to model the radicalisation process (Silva, 2018). This has resulted in governments and their partners around the world introducing a diverse range of interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence that are underpinned by different approaches to prevention, different theories of change, and different models of radicalisation (Hardy, 2018).

There is an important distinction between ‘cognitive’ and ‘behavioural’ models of radicalisation (Neumann, 2013; Vergani et al., 2020; Wolfowicz et al., 2021). Whilst cognitive approaches understand radicalisation as the process by which individuals adopt extremist beliefs, behavioural models frame radicalisation as the process by which individuals become involved in violent behaviour. Interventions underpinned by the former model of radicalisation typically have a broader focus than those that are more explicitly focused on preventing violent behaviour given that a broad range of beliefs—including beliefs that are not explicitly violent—have been defined as ‘extremist’ by some governments (Schmid, 2014).

Whilst the precise nature of the causal relationship between extremist beliefs and violent action is unclear (Borum, 2012), both cognitive and behavioural models frame radicalisation as the process by which individuals transition closer towards violent action. Within cognitive models, the adoption of extremist beliefs is seen to increase the risk of an individual becoming involved in violence (Schmid, 2014), whilst involvement in violence is the end‐point of behavioural models (Neumann, 2013). In turn, interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence include programmes that are designed to counter violent extremist beliefs as well as those that are more explicitly focused on countering violent behaviour (Hardy, 2018; Neumann, 2013; Schmid, 2014; Sedgwick, 2010). This review will therefore consider case management interventions underpinned by both cognitive and behavioural models of radicalisation to violence that seek to a) tackle risk factors believed to contribute to cognitive and/or behavioural radicalisation; and/or b) strengthen protective factors believed to mitigate against both forms of radicalisation (see Wolfowicz et al., 2021). Interventions that seek to tackle broader forms of cognitive radicalisation (i.e., the adoption of non‐violent ‘extreme’ beliefs) will not be included, unless this work is explicitly linked to the prevention of violence.

1.2.2. Interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence

The terms ‘PVE’ (preventing violent extremism) and ‘CVE’ (countering violent extremism) are often used to describe the increasingly diverse range of interventions that are designed to counter radicalisation to violence. The P/CVE field is complex, with a range of governmental and non‐governmental actors now delivering a variety of interventions. These are often categorised using the public health model of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention (e.g., Bhui & Jones, 2017; Marsden et al., 2017). In practice, the distinction between these different stages of prevention is often not absolute, and individual P/CVE interventions may span multiple stages (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). However, the distinction between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention is useful for distinguishing between different elements of P/CVE programming.

Primary interventions are ‘broad‐based, mass prevention programmes that target the general population’ to build ‘individual and communal ‘resilience’ against radicalisation’ (Elshimi, 2020, p. 234). A prominent example of primary prevention is the delivery of whole‐school educational initiatives to build pupils' awareness and understanding of the risk of radicalisation (Sjøen & Jore, 2019; Wallner, 2020). Several of these interventions have reported positive results against intended outcomes (e.g., Parker & Lindekilde, 2020). However, whilst primary interventions are crucial to a ‘whole of society’ approach to countering radicalisation, the fact that they operate in a ‘pre‐risk stage’ (Elshimi, 2020, p. 229) means that the relationship between their outcomes and individual involvement in violent extremism is not always clear. Primary interventions are therefore not included in this review.

Secondary and tertiary interventions are more explicitly focused on preventing individuals from radicalising towards and/or engaging in violence. Secondary interventions work with ‘at risk’ individuals or groups to ‘prevent the progression of radicalisation and reduce the potential for future radicalisation’ (Elshimi, 2020, p. 235). Tertiary interventions work with those already engaged in violent extremism to facilitate disengagement processes and desistance from violence, which might include engaging with family members and relevant persons from within the social network of radicalised individuals (Elshimi, 2020). It is in the secondary and tertiary prevention space that case management tools and approaches are becoming increasingly common, with prominent examples of case‐managed counter‐radicalisation interventions and programmes including Channel (HMG, 2020) and the Desistance and Disengagement Programme (DDP) in the UK (Elshimi, 2020), and the Countering Violent Extremism Early Intervention Program (CVE‐EIP) (Harris‐Hogan, 2020) and Proactive Integrated Support Model (PRISM) (Cherney & Belton, 2021a) in Australia. Given their explicit focus on delivering outcomes relevant to countering radicalisation to violence, this review defines secondary and tertiary interventions operating in this context as ‘counter‐radicalisation interventions’, and avoids using the term P/CVE for the sake of clarity.

Part I of the review will examine case management counter‐radicalisation interventions, and/or their associated tools and approaches, as defined in Section 1.2.4–6 below. This might include evidence from standalone case management interventions such as Channel or PRISM, as well as evidence from more ‘comprehensive’ programmes that utilise a case management component as part of a broader suite of different interventions (see Hodgkinson et al., 2009).

1.2.3. Defining ‘Violence’

This review defines violence as ‘[t]he intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual’ that ‘either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal‐development, or deprivation’ (Dahlberg & Krug, 2002, p. 5). Violence can be categorised as either collective; interpersonal; or self‐directed (Dahlberg & Krug, 2002). Part II of the review focuses on interventions seeking to tackle collective and interpersonal violence which, as noted in Section 1.1.2, are increasingly seen as being transferable to counter‐radicalisation work. Interventions for self‐directed violence will be excluded. The review adopts the following definitions of collective and interpersonal violence:

-

a.

Collective Violence: Physical, psychological or sexual violence perpetrated by those acting as part of a collective such as gang‐related violence (e.g., Randhawa‐Horne et al., 2019) or larger‐scale militancy (e.g., USAID, 2021).

-

b.

Interpersonal Violence: Physical, psychological or sexual violence perpetrated by individuals (or small groups of individuals) against other people (Mercy et al., 2017), including family members or partners (e.g., Gondolf, 2008).

Secondary and tertiary interventions seeking to tackle collective (e.g., Brantingham et al., 2021; Engel et al., 2013) and interpersonal (e.g., Gondolf, 2008) forms of violence are also increasingly using case management tools and approaches in work with clients. The obvious relevance of research examining these interventions for policymakers and practitioners working to counter radicalisation to violence is illustrated by the fact that case management interventions seeking to counter violence more broadly have been used to tackle ideologically‐motivated violence (Weine et al., 2021), and have been used as a foundation for developing interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence (Weine et al., 2018).

In line with Part I, Part II will consider evidence from secondary and tertiary case management interventions, and their related tools and approaches, seeking to prevent individuals from engaging in, or promote disengagement/desistance from any type of violence, including but not limited to phenomena such as domestic violence, gang‐related violence, and militancy.

1.2.4. The case management process

Case management interventions range from more light‐touch and short‐term ‘brokerage’ models, in which a broker connects clients with different forms of support, through to more ‘intensive’ or ‘assertive’ approaches in which case managers take a more prolonged role in supporting their clients (Lukersmith et al., 2016). Parts I and II of the review will include interventions that use any model of case management. However, as research would suggest that case management interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence predominantly use more intensive models of case management (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a; HMG, 2020), it is expected that the most relevant lessons from the broader field of violence prevention (i.e., interventions included in Stage II of the review) will be drawn from case management interventions that use similarly intensive models as outlined in Figure 1.

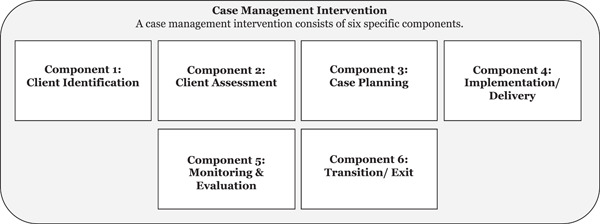

Figure 1.

The intensive case management process (based on NCMN, 2009).

The intensive approach to case management is often understood as comprising several components (see Figure 1) including client identification; client assessment; case planning; care implementation/co‐ordination; evaluation and monitoring; and transition/exit (NCMN, 2009; Ross et al., 2011). Whilst the specific terminology and exact definitions used by different organisations can vary, these components are evident in guidance produced by professional bodies such as the Case Management Society UK (CMSUK) and Canada's National Case Management Network (NCMN) (CMSUK, 2009; NCMN, 2009). A defining feature of this approach is that it is client‐centred, as shown in the definitions below:

[Case management is] a collaborative process which assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors and evaluates the options and services required to meet an individual's health, care, educational and employment needs, using communication and available resources to promote quality cost effective outcomes.

(CMSUK, 2009, p. 8)

Case Management is a collaborative, client‐driven process for the provision of quality health and support services through the effective and efficient use of resources. Case Management supports the clients’ achievement of safe, realistic, and reasonable goals within a complex health, social, and fiscal environment.

(NCMN, 2009, p. 7)

Critics of case management have argued that this approach ‘places an untoward emphasis on ‘managing’ cases, addressing outcomes without a commitment to process and relentless attention to cost‐effectiveness’ (Gursansky et al., 2020, p. 4). However, the fundamental principle of case management outlined in the above definitions—that each individual client is provided with a co‐ordinated package of support that is tailored to their specific needs and circumstances (Gursansky et al., 2020)—appears well‐suited to efforts to prevent, interrupt and counter radicalisation to violence (Zeuthen, 2021).

A staged case management process should provide a foundation for: identifying the needs of individual clients and for setting client goals (assessment); for developing and delivering work plans tailored to these needs (planning and implementation); for measuring and monitoring a client's progress (evaluating and monitoring); and for assessing whether the work plan has effectively met the client's needs or delivered specific client‐level outcome measures (transition). Research would suggest that case management interventions in this field are commonly designed to work in this way (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Weeks, 2018), but a variety of case management tools and approaches may be used across different programmes.

This review uses the terms tools and approaches to examine two distinct, but related, elements of case management interventions. These concepts are distinguished as follows:

-

–

The term tools is used to refer to the procedures or methods that are used to identify individuals eligible for interventions; assess their treatment needs; develop and deliver intervention plans; monitor and evaluate their progress and treatment outcomes; and determine when the client is eligible to exit the intervention.

-

–

The term approaches is used in the same way as in the White et al. (2021) evidence and gap map of interventions seeking to prevent children getting involved in violence to refer to the different theories of change or intervention logics that underpin case management interventions, whether implicit or explicit.

1.2.5. Case management tools

A range of tools may be used across different stages of the case management process, and to capture client‐level progress and outcome measures (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020). Examples of three such tools are discussed below.

Risk assessment tools

There is a robust body of research that has examined various risk assessment tools currently being used to assess an individual's risk of violence (see Hurducas et al., 2014; Scarcella et al., 2016). These include tools that have been specifically developed for use in case management interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence (see Lloyd, 2019). Prominent examples include the Extremism Risk Guidance 22+ (ERG22+) (Lloyd & Dean, 2015); the Violent Extremism Risk Assessment Version 2 Revised (VERA‐2R) (Pressman, 2009); and the Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol (TRAP‐18) (Meloy et al., 2015).

The primary function of these tools is the initial assessment of clients. However, there is considerable variation in the number and types of indicators included in different tools. For example, Lloyd (2019) notes that several tools explicitly capture protective factors alongside risk factors (e.g., VERA‐2R), whilst others only focus on risk factors. There are also some tools that assess protective factors only (e.g., Abbiati et al., 2020). This means that the specific assessment tool used may influence the types and range of client needs identified and targeted.

Many of these risk assessment tools are used across multiple stages of the case management process. They may be used to develop case plans to mitigate risk factors and/or strengthen protective factors identified in initial client assessments, to monitor clients and assess client‐level progress, and to determine when clients are eligible to exit the intervention (Lloyd & Dean, 2015; Lloyd, 2019). For example, official guidance for the UK's Channel programme states that the same risk assessment tool—the Vulnerability Assessment Framework (VAF), which is based on the ERG 22+ tool mentioned above (Augestad, 2020)—should be used across all stages of the case management process. Each client has a ‘Channel Case Officer’ who is responsible for ‘updating the VAF and for assessing [client] progress’, with the expectation being that the VAF will be updated every three months as a minimum ‘to ensure that the progress being made in supporting the individual is being captured’ (HMG, 2020, p. 36). The VAF should also be reassessed when it is needed ‘to inform a key panel meeting’; ‘where the provision of support has reached a particular milestone’, or where there have been ‘significant changes to circumstances or levels of risk’ (HMG, 2020, p. 36). If the Case Officer and a multi‐agency panel is satisfied that an individual's level of risk has been sufficiently reduced upon completion of their work plan, the case will be closed, and a final VAF will be completed.

Case planning tools

Whilst several of the risk assessment tools listed above are explicitly designed to be used to inform case planning (Lloyd, 2019), exploratory research from other fields has also suggested that dedicated case planning tools could be used to ensure that case plans accurately reflect and target the issues identified by assessments tools (Viljoen et al., 2018, 2019). There has been little research into the use of case planning tools in the field of countering radicalisation to violence or related phenomena. However, insights from the wider field of violent offending highlights the limitations of relying solely on data collected from risk assessment tools when developing work plans (Viljoen et al., 2018, 2019). Whilst risk assessment tools can be used throughout the case management process, additional data will likely be needed to ensure that interventions are delivered in ways that are consistent with their own internal logic; that intervention plans are appropriate for targeting the risk/protective factors identified by risk assessments; and that the support delivered to each individual clients is in turn consistent with their original intervention plan. These are all issues that could be addressed by using case planning tools.

Monitoring and evaluation tools

Potential sources of monitoring and evaluation data include administrative data relating to a client's participation in an intervention (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020), or information about a client's activities outside of the intervention gleaned from family members or peers (Cherney, 2021; Meloy, 2018). Case notes are likely to be a particularly important data collection and analysis tool (Cherney & Belton, 2021a; Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020; Meloy, 2018). Case notes may be compiled using pre‐defined templates or may be more ad hoc (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020), and completed by one or multiple practitioners throughout an intervention (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Case notes containing an appropriate level of detail will include information which can be used to identify client‐level progress and outcome measures, and to assess progress against said measures (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). As Cherney, Belton, and Koehler (2020, p. 23) outline, this might include ‘risk assessment data, criminal history (if applicable), and detailed information of client radicalisation (including triggering events); treatment plans and intervention goals and how clients are progressing towards these goals (milestones achieved); and contact and interactions with clients’. In summary, a diverse range of tools may be used across different stages of the case management process, and more research is needed to understand how these tools are being used in practice.

1.2.6. Case management approaches

Researchers often distinguish between different counter‐radicalisation ‘approaches’ that are underpinned by different theories of change. Most notably, a distinction is often drawn between ‘strengths‐based’ and ‘risk‐oriented’ approaches to countering radicalisation (e.g., Marsden, 2017). These are informed by different assumptions about how best to counter radicalisation; both approaches are discussed in the analysis of mechanisms below.

In many cases, the assumptions, or theory of change, underpinning interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence are not explicit (Lewis et al., 2020). This means that identifying and examining different approaches to case management can be challenging. However, it is possible to identify and map the different approaches being used to counter radicalisation to violence by examining the constituent parts of each intervention's theory of change—implicit or explicit—and to synthesise evidence relating to interventions underpinned by similar assumptions.

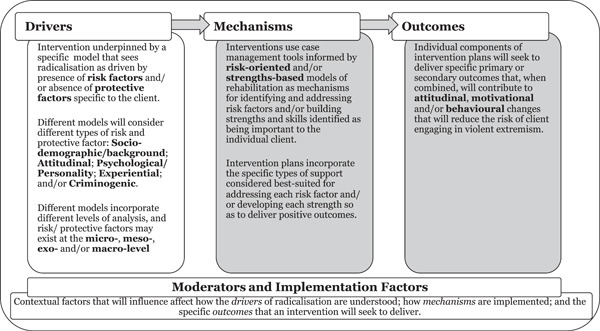

All interventions seeking to counter violence are underpinned by implicit or explicit assumptions about the drivers of violence, and how violence is best prevented (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020). These assumptions can be identified by breaking down an intervention's theory of change into its constituent parts. Cherney, Belton, and Koehler (2020, pp. 12–13) note that ‘developing a theory of change requires consideration of what will be targeted (which drivers of violent extremism) and how they will be targeted (mechanisms) to achieve what (outcomes), which will be influenced by certain factors (moderators and implementation processes)’. Different approaches to case management can be categorised using the four domains of drivers, mechanisms, outcomes and moderators (Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Case management intervention theory of change.

The sub‐sections below draw on existing research on radicalisation and counter‐radicalisation and discuss how different approaches to case management can be identified by unpicking the constituent parts of their theories of change. Whilst the discussion below is oriented towards Part I of the review, and therefore focuses on case management interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence, it is illustrative of how different approaches to case management more broadly (i.e., including those examined in Part II) can be differentiated.

Case management approaches I: Drivers

Radicalisation is commonly understood as a process that is driven by the presence of risk factors and/or the absence of protective factors, with different models of radicalisation placing different weight on the relative importance of risk versus protective factors (see Vergani et al., 2020; Wolfowicz et al., 2021). Interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence often consider both risk and protective factors (Dean, 2014). However, there may be variation in how explicitly an intervention (and associated tools) focuses on the latter (Table 1). Interventions can be interpreted in relation to the relative weight they place on risk and protective factors throughout the different stages of the case management process outlined in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Interventions and drivers of radicalisation.

| Primary focus of Intervention | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Intervention and its associated tools only focus on identifying and tackling risk factors, or pay limited attention to protective factors. |

| Protective factors | Intervention genuinely integrates protective factors and resilience‐building activities. |

Different types of risk/protective factor that an intervention might focus on

The relationship between risk and protective factors is complex and contested (Lösel et al., 2018). However, it is common to interpret them thematically. For example, Wolfowicz et al. (2021) Campbell systematic review of risk and protective factors for cognitive and behavioural radicalisation categorised risk and protective factors across five domains (see Table 2 below). Whilst it might be expected that interventions would consider multiple domains, the specific focus of each intervention may vary according to the model of radicalisation that underpins it (Hardy, 2018), or the broader theories of (violent) human behaviour that underpin violence prevention programmes, and in the context of case management, the needs of each client.

Table 2.

Different domains (Wolfowicz et al., 2021).

| Domain | Examples |

|---|---|

| Socio‐demographic/background: Individual characteristics that might contribute to, or mitigate against, radicalisation risk.a | Risk Factors |

| Unemployment, alcohol or substance abuse, relationship problems etc. | |

| Protective Factors | |

| Socio‐economic status, education etc. | |

| Attitudinal factors | Risk Factor |

| Holding specific attitudes or perceptions about the world that can contribute to, or mitigate against, radicalisation risk. | Perceived in‐group superiority, perceived discrimination, perceived injustice etc. |

| Protective Factors | |

| Law abidance, belief in legitimacy of the law, trust in institutions, trust in others, social support, perceived self‐efficacy etc. | |

| Psychological/Personality factors | Risk Factors |

| Psychological or personality traits that can contribute to, or mitigate against, radicalisation risk. | Mental health issues, anger, negative affect, authoritarianism etc. |

| Protective Factors | |

| Life satisfaction, higher self‐esteem etc. | |

| Experiential | Risk Factors |

| Life experiences that can contribute to, or mitigate against, radicalisation risk. | Prior incarceration, experience of discrimination, traumatic experiences etc. |

| Protective Factors | |

| High perceptions of procedural justice. | |

| Criminogenic | Risk Factors |

| Traditional risk/protective factors cited as relevant to other types of criminal offending. | Criminal history, deviant/radical peers, low self‐control, thrill seeking etc. |

| Protective Factors | |

| Parental involvement, school bonding, outgroup friends etc. |

Of course, interventions are not able to change many factors captured by this domain (e.g., age, gender).

Risk/protective factors existing at different levels of analysis

Risk and protective factors operate at different levels of analysis. Most commonly, authors identify three levels of analysis: individual (or micro‐level); social (or meso‐level) and structural (or macro‐level) drivers (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020; Schmid, 2013). However, some models also distinguish between meso‐level and exo‐level drivers of radicalisation, the former referring to influences operating in an individual's immediate environment such as family or peers, and the latter to ‘more distal environmental influences such as community organizations’ (Ellis et al., 2022, p.2). Whilst some interventions continue to focus solely on the micro‐level of analysis (e.g., Muluk et al., 2020), a range of interventions—including those that using case management tools—now take a ‘socio‐ecological’ approach to understanding vulnerability and/or resilience (e.g., Ellis et al., 2022; Grossman et al., 2022). These socio‐ecological interventions explicitly consider and seek to address risk and protective factors existing in an individual's micro‐, meso‐, exo‐, and macro‐system (Ellis et al., 2022). Interventions can therefore be differentiated according to the levels of social ecology considered when assessing risk and protective factors (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Different levels of analysis (based on Ellis et al., 2022).

| Code | Examples |

|---|---|

| Micro‐level | Background factors such as those shown in Table 2 |

| Individual characteristics | |

| Meso‐level | Extremist peers or family members (Kenney & Chernov Hwang, 2021); Poor familial relationships or household dysfunction (Gill et al., 2021) |

| Factors found in the immediate environment | |

| Exo‐level | Neighbourhood context (Neve et al., 2020) |

| Distal environmental factors | |

| Macro‐level | Political or societal discrimination against group (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020); Increased availability of extremist propaganda or increasing radicalism of mainstream (Ellis et al., 2022). |

| Larger social and cultural context |

Case management approaches II: Mechanisms

Mechanisms refer to the specific ways in which the drivers of radicalisation/other forms of violence will be targeted to produce desired outcomes (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020). The mechanisms underpinning interventions are characteristic of, and therefore can help identify, the different models of rehabilitation that inform the use of case management tools and the delivery of specific types of support to case‐managed clients. One of the core distinctions is between ‘risk‐oriented’ models and ‘strengths‐based’ models of rehabilitation. Each model is underpinned by different assumptions about the mechanisms that might be used to prevent engagement in, or facilitate disengagement from, violent extremism.

Counter‐radicalisation interventions have traditionally been rooted in risk‐oriented models of rehabilitation (Marsden, 2017). A risk‐oriented case management approach can be identified implicitly through the use of specific tools, such as risk assessment tools that fail to capture protective factors (see above), or explicitly through reference to specific models such as the Risk‐Needs‐Responsivity (RNR) model of case management which has long dominated in post‐conviction contexts (Bonta & Andrews, 2017). Interventions underpinned by the RNR model attempt to manage risk by tailoring intervention plans to each client's level of risk (with higher‐risk individuals receiving more intensive support), to their specific needs, in a way that is responsive to their specific characteristics and circumstances (Dean, 2014; Marsden, 2017).

The RNR approach is underpinned by a robust evidence base within the field of criminology (Bonta & Andrews, 2010), and has been used in the counter‐radicalisation context (e.g., Dean, 2014). However, researchers are increasingly calling for, and in some cases have developed, interventions that use strengths‐based approaches as mechanisms for countering radicalisation to violence (Cherney, 2021; Marsden, 2017).

Strengths‐based approaches can be distinguished implicitly through the use of tools that orient interventions towards the development of strengths or skills that are believed to contribute to rehabilitation. They can also be identified by the explicit use of strengths‐based or desistance‐informed approaches such as the Good Lives Model (GLM) which place greater emphasis on building those strengths believed to contribute to desistance (Dean, 2014).

Strengths‐based approaches seek to promote the strengths of offenders so they can satisfy their needs without resorting to violence (Marsden, 2017). Desistance‐oriented approaches focus on identifying and leveraging factors that explain why individuals desist from, or do not become engaged in, violence (Marsden, 2017). This distinction between risk‐oriented and strengths‐based approaches will make a particularly useful contribution, as it will speak directly to a long‐standing debate about the virtue of using these different approaches to tackling radicalisation and other social harms (Cherney, 2021; Horan et al., 2020; Marsden, 2017). Proponents of strengths‐based or desistance approaches argue that risk‐oriented approaches are too ‘deficit focused’ (Wong & Horan, 2021). Further, that secondary and tertiary interventions would be better served by focusing on developing clients’ internal strengths so that they are able to pursue more pro‐social ways of meeting the needs that might otherwise be served through engagement in violent (extremist) behaviour (Marsden, 2017). This review aims to contribute to this debate by examining and contrasting these different approaches.

Case management approaches III: Outcomes

The ultimate aim of case management interventions is the prevention of future violent extremist behaviour. However, individual components of these interventions may seek to deliver more specific outcomes that are believed to contribute to the over‐arching goal of countering radicalisation to violence. These outcomes may be informed by risk‐oriented approaches, and in turn be used to measure the effectiveness of an intervention at tackling different radical outcomes such as those set out in systematic reviews conducted by Wolfowicz et al. (2021) and Lösel et al. (2018), which focus on attitudes, motivations, and behaviours.

However, outcomes may also be strengths‐based. These are more oriented towards the development of key strengths and skills that are believed to contribute to disengagement from violent extremism, such as the development of pro‐social supports, education and training, and employment (Cherney & Belton, 2021a, 2021b). Individual components of intervention plans may seek to deliver these outcomes explicitly or implicitly. For example, case management plans may incorporate counter‐ideological or counter‐narrative work that is explicitly designed to tackle a client's violent extremist attitudes. However, they might also attempt to tackle these attitudes implicitly by seeking to address broader issues identified in the client's life believed to make them receptive to extremist ideology in the first place.

In this way, different approaches to case management can be identified by examining the primary and secondary outcomes that an individual intervention seeks to deliver. Whilst many counter‐radicalisation interventions do not explicitly adhere to the models of rehabilitation outlined in the section on mechanisms above, their implicit use of these mechanisms can be determined by assessing whether their intended outcomes align with the key assumptions underpinning RNR, strengths‐based, and desistance‐oriented frameworks.

Case management approaches IV: Moderator and implementation factors

Moderators refer to ‘contextual conditions’ or the ‘features of the people or places that are the target for intervention’ (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020, p. 15). The contextual conditions of case management interventions may vary in regard to, for example, the delivery context (e.g., pre‐ vs. post‐conviction settings; correctional vs. community‐based interventions, etc.); and profiles of individual clients (e.g., demographics; social context, etc.).

Implementation factors refer to ‘actions or actors necessary to successfully install and maintain an intervention’ (Cherney, Belton, & Koehler, 2020, p. 16). These factors might include the number and type of delivery agents involved in delivering an intervention; how the specific stages of case management are implemented in practice (e.g., when and how frequently are risk assessments conducted? Who conducts risk assessments? What is the duration of follow‐up etc.); and a range of contextual factors that might influence how an intervention is implemented (and in turn, its effectiveness), such as staffing levels (Wolff et al., 2022); the quality of training received by case managers/other key staff (Radcliffe et al., 2018), or the size of each case manager's caseload (Fox et al., 2022).

1.3. How the intervention might work

There is no single approach to delivering case management. Below is an illustrative example of how each stage of the case management process might work when engaging with clients who are at risk of becoming involved or who are already involved in violent extremism.

1.3.1. Planning: Identification, assessment and case planning

In secondary interventions, ‘at‐risk’ individuals may be identified through different channels. In the UK for example, the 2015 Prevent Duty placed a range of public institutions under a statutory duty to have ‘due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism’ (HMG, 2021). This led to an increase in the number of individuals being referred to Channel, with referrals coming from a diverse range of sectors including healthcare, education and the police (Home Office, 2020).1 Whilst the UK is currently one of the only countries to legally mandate that public institutions have a means of identifying and reporting those who may be at risk of radicalisation, public sector workers in other countries perform a similar counter‐extremism function (Harris‐Hogan, 2020; Parker et al., 2021; Wallner, 2020).

A number of interventions, including Channel, use multi‐agency panels to assess individuals seen as potentially at risk of radicalisation (Ellis et al., 2022; Harris‐Hogan, 2020; HMG, 2020). A significant number of initial referrals may be screened by gatekeepers (such as local counter‐radicalisation practitioners) without going forward for formal assessment (HMG, 2020). Referrals taken forward to a multi‐agency panel will be assessed to determine whether they require a counter‐radicalisation intervention or if they need to be signposted to other forms of support. As noted above, there are a range of existing risk assessment tools that can be used to inform this decision. For example, decisions around whether to adopt an individual as a Channel case are made by local multi‐agency panels using the VAF (Pettinger, 2020).

Where an individual is assessed as in need of a counter‐radicalisation intervention, the panel designs a comprehensive work plan to address the client's specific vulnerabilities, and/or to build protective factors at the individual and/or the socio‐ecological level (e.g., Ellis et al., 2022). Work plans may be further tailored to the individual client in a number of ways. For example, case managers may decide to tailor the specific intervention providers used, or may sequence the different components of the work plan so they are delivered according to each individual client's needs or learning style (Cherney & Belton, 2021b). The specific focus of this work plan is likely to vary according to whether the intervention is underpinned by a risk‐based or strengths‐based approach, with the former focused on tackling risk factors seen as contributing to radicalisation, and the latter on building protective factors (Marsden, 2017).

Case management in tertiary interventions operates in a similar way. For example, interventions operating in post‐conviction settings use similar risk assessment tools—including those listed earlier—to assess the intervention needs of individuals who have been convicted for terrorism‐related offences, as well as those who are suspected of becoming radicalised during their incarceration. The results of these assessments inform the development of tailored intervention plans (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). One notable difference is that whilst engagement in secondary interventions tends to be on a voluntary basis, engagement in some tertiary interventions is mandatory (Elshimi, 2020), and there is some debate as to whether mandating participation is effective (Cherney et al., 2021).

Clients of both secondary and tertiary programmes are supposed to be provided with holistic intervention plans incorporating different types of support, including psychological, social, theological or ideological components (Cherney & Belton, 2021b). Whilst a number of intervention providers may be tasked with delivering these various forms of support, the delivery of individual intervention plans is typically co‐ordinated by a specific case manager, who is responsible for monitoring client‐level progress and outcomes—often with input from the intervention providers (Cherney & Belton, 2021b; Harris‐Hogan, 2020; HMG, 2020).

1.3.2. Delivery: Implementation, monitoring, evaluation and transition

The theories of change underpinning case management interventions are often not explicit which means the relationships between an intervention's activities and outcomes are not always clear (Lewis et al., 2020). There can also be variation across programmes as to the individual‐, community‐, and programme‐level outcomes they are seeking to achieve (Cherney et al., 2018; Harris‐Hogan, 2020). For example, whilst some tertiary interventions seek to promote desistance and disengagement by ‘deradicalising’ clients so they reject extremist ideology (El‐Said, 2012; Khalil et al., 2019), there is some debate as to whether deradicalisation is possible or needed to promote the rehabilitation and reintegration of violent extremists (Horgan & Braddock, 2010). As a result, deradicalisation is not always an explicit objective of tertiary interventions. However, case management interventions are a specific type of ‘risk reduction initiative’ (Horgan & Braddock, 2010) as they are designed to reduce the risk of an individual becoming radicalised (secondary), or reduce the risk of an individual becoming re‐engaged in violent extremism by promoting their desistance, disengagement and/or deradicalisation (tertiary). And, as noted above, a diverse range of risk assessment tools and other data sources may be used to monitor an individual's participation in, or compliance with, an intervention plan; to monitor relevant attitudinal and behavioural changes over time; and to inform exit decisions.

1.4. Why it is important to do this review

Case management interventions are increasingly used by governments and their partners to prevent engagement in, and promote disengagement from, violent extremism (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Whilst several of these programmes are long‐established, they have come under scrutiny in recent years in the wake of high‐profile terrorist attacks (Clubb et al., 2021). For example, the UK's Desistance and Disengagement Programme (DDP) (see Elshimi, 2020) attracted public attention when it became known that Usman Khan, who killed two people in a terrorist attack in 2019, had taken part in the programme. This raised questions around the extent to which intervention providers had effectively identified and addressed the specific issues present in this individual case, and the extent to which existing tools were effectively able to assess the level of risk posed by Khan upon his release from prison. The fact that Khan had been released on license also raised questions about how to monitor client progress post‐release, which is a challenge identified by practitioners in other countries (Cherney, 2021).

By incorporating two distinct, inter‐related parts, this review will make a number of important contributions that are timely to policymakers and researchers dealing with these questions.

1.4.1. The importance of reviewing existing case management tools and approaches

Part I of this review will make three specific contributions. First, it will synthesise evidence from a field in which the principles of case management are often embedded in interventions, but the specific term ‘case management’ is rarely used. Bar a small number of exceptions (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a), many client‐focused interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence do not explicitly use the term ‘case management’, which hampers evidence synthesis. By breaking down case management into its constituent parts (e.g., client identification; client assessment; care planning; implementation/co‐ordination; evaluation and monitoring; and transition/exit) Part I will identify and synthesise evidence relevant to different phases of case management, including studies that do not specifically use this term.

Second, whilst a number of empirical studies have examined the psychometric properties of risk assessment tools used in case management counter‐radicalisation interventions (see Lloyd, 2019), there has yet to be any systematic research that synthesises knowledge about how these tools are used in practice. Whilst it would be expected that validated risk assessment tools are being used to inform case planning and intervention delivery, research from other fields of violence prevention shows this is not always true in practice (Viljoen et al., 2018). This review will complement the systematic review into the psychometric validity of these tools (Hassan et al., 2022) by examining how tools are being used across the case management process to inform the development and delivery of client‐focused intervention plans, and to monitor and evaluate client progress and outcomes. This will provide a more holistic overview of how the different stages of the case management process are being operationalised within counter‐radicalisation interventions than currently exists.

Third, by synthesising evidence relating to different approaches to case management (e.g., strengths‐based approaches; risk‐oriented approaches, etc.) this review will attempt to make the implicit assumptions that underpin counter‐radicalisation interventions more explicit, and to examine the validity of different assumptions more systematically than has been done previously. This review does not examine the individual components of each intervention's theory of change (i.e., the specific change mechanism). Instead, it attempts to synthesise evidence relating to each over‐arching case management approach that is used in this space. This analysis is aligned with Hodgkinson et al.'s (2009) widely‐cited systematic review of ‘comprehensive’ anti‐gang interventions, in which the authors argued it was ‘valuable to examine the effectiveness of interventions grouped by [different] theories of change’ (p.45).

The importance of this type of analysis is illustrated by a recent systematic review of the Good Lives Model (GLM) conducted by Mallion et al. (2020), which, as noted above, is a specific approach that has been used to inform counter‐radicalisation interventions (Dean, 2014). This review set out to test the effectiveness of the GLM in the context of a range of offence types, as well as examine the assumptions on which it is based. These assumptions include the idea that all individuals are driven by a desire to live a good life, and that offending occurs when an individual faces barriers that prevent them from pursuing ‘primary goods’ that contribute to a good life—such as success in one's professional or personal life, a sense of community, etc.—in a pro‐social way. Mallion et al.'s review only included interventions explicitly stating that they were using a GLM approach, and which were delivered in a GLM‐consistent way (i.e., that identified primary goods relevant to the client and the barriers to pursuing them in pro‐social ways, and tailored the intervention accordingly). By synthesising evidence drawn from interventions sharing a common approach, this review was able to examine the assumptions underpinning the GLM; and the effectiveness of GLM‐informed interventions. Their review therefore provides a template for identifying different approaches by reviewing the underlying assumptions of an intervention, for assessing an approach's effectiveness in terms of impact on client‐level outcomes, and for evaluating whether an intervention is implemented in a way that is consistent with these underlying assumptions.

1.4.2. The importance of learning from other fields

The limitations of the evidence base underpinning counter‐radicalisation interventions are well‐established (Baruch et al., 2018; Bellasio et al., 2018; Feddes & Gallucci, 2015; Pistone et al., 2019). It is extremely challenging to evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions given the difficulty in accessing data, the small samples of intervention participants, and the absence of an obvious counterfactual (Lewis et al., 2020). Ethical and national security considerations have also limited the use of experimental or more robust quasi‐experimental designs when evaluating secondary or tertiary interventions on the basis that it would be unethical (and potentially unsafe) to deny or delay the delivery of a counter‐radicalisation intervention to a control group simply for the purposes of evaluating it (Braddock, 2020; Lewis et al., 2020). Consequently, existing case management interventions have not been systematically evaluated, and the field lacks agreed measures to assess client‐level progress and outcomes (Cherney & Belton, 2021a). Although authors have discussed potential solutions to these evaluation challenges by drawing on lessons from other fields (e.g., Baruch et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2017; Lewis et al., 2020), the solutions proposed have yet to be applied in practice.

Part II of this review is specifically designed to address known weaknesses in the evidence‐base underpinning interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence. Whilst the overlap between the broader field of violence prevention and counter‐radicalisation should not be overstated, the staged counter‐radicalisation case management process outlined in Section 1.3—and the tools and approaches associated with each stage of the process—is similar to how intensive models of case management are known to operate in other fields. Given that several violence reduction interventions which incorporate a case management component have been subject to the type of robust evaluation that has often been lacking in the field of counter‐radicalisation (e.g., Brantingham et al., 2021; College of Policing, 2021a; Romaniuk & Davies, 2017; Weine et al., 2021), evidence from broader violence prevention work may provide a more robust evidence‐base with which to examine whether case management tools and approaches can be effective in countering violent attitudes and behaviours, and exploring how they might directly contribute to these types of outcomes.

By reviewing research on case management interventions seeking to tackle other forms of violence, Part II of the review seeks to identify evidence from related fields that could be used to inform interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence. This part of the review meets the Cochrane collaboration definition for an ‘overview of reviews’ (Pollock et al., 2021) on the basis that it will summarise evidence from systematic reviews ‘of the same intervention for different conditions or populations’ (i.e., case management interventions seeing to counter different forms of non‐extremist violence). However, Part II of the review will go further than an overview of reviews traditionally would, as it will examine the transferability of this evidence to another distinct but related field, namely countering radicalisation to violence. In this way, whilst the two parts of this review examine different types of violence and use different methodologies, they are interconnected, and will both have important implications for research, policy and practice in the field of countering radicalisation to violence on the basis that the objectives for both stages of the review are firmly orientated towards this field.

1.4.3. Potential importance to policymakers and practitioners

This review speaks directly to concerns that have been raised by policymakers and by public commentators about the efficacy of case management counter‐radicalisation interventions. It does so in two ways. First, by synthesising evidence from an ever‐expanding and complex literature on counter‐radicalisation, Part I of the review aims to contribute to policy and practice by (a) examining whether the use of case management in this context is supported by evidence; (b) providing a robust assessment of the potential efficacy of case management in this context, and ‘what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances’ (Gielen, 2018); and (c) identifying areas of good practice that could be used to inform programme development. Second, by drawing on evidence from outside of the field of countering radicalisation to violence, Part II of the review aims to provide a foundation for policymakers and practitioners to learn from the use of case management in more established fields of violence prevention.

2. OBJECTIVES

Whilst Parts I and II of this review examine interventions seeking to counter different but related problems, both parts seek to deliver comparable analyses by (1) examining the effectiveness of case management tools and approaches in delivering primary and secondary outcomes relevant to countering violence; and (2) examining the processes by which these tools and approaches are implemented in practice. This twin focus is informed by guidance for conducting evaluations of terrorism risk reduction programmes developed by Williams and Kleinman (2014). This approach proposes that such evaluations should be ‘designed to understand both what is being done by the initiative, and how faithfully/consistently its components are implemented’ (p. 114). It is also aligned with Viljoen et al.'s systematic review into whether the use of risk assessment tools helps to reduce violence risk, which argues that:

violence reduction is not the only possible indicator of tools’ impact. If risk assessment tools do, indeed, reduce violence and offending, this relationship may be indirect, and contingent upon professionals’ risk management practices.

(Viljoen et al., 2018, p. 184)

The primary objectives of this review are therefore to synthesise:

-

(1)

Evidence relating to the effectiveness of the different case management tools and approaches that are currently being used to counter radicalisation to violence.

-

(2)

Evidence relating to the implementation of these tools and approaches.

-

(3)

Identify relevant insights from wider research on interventions seeking to counter other forms of violence and assess their transferability to counter‐radicalisation work.

Parts I and II of the review are guided by specific research questions.

Part I: Evaluating Case Management Counter‐Radicalisation Interventions

| RQ | Question | Objective | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | To what extent are different case management tools or approaches effective at countering radicalisation to violence? | Synthesise evidence relating to outcomes capturing the effectiveness of a tool or approach at countering radicalisation to violence. This analysis examines: | Narrative summary of all included studies. |

| (i) Primary outcomes (i.e., measures of disengagement, desistance, and deradicalisation); and | Meta‐analysis of experimental/stronger quasi‐experimental quantitative studies. | ||

| (ii) Secondary outcomes (i.e., measures of client engagement or motivation; measures capturing attitudinal or behavioural changes relevant to primary outcomes). | Alternative synthesis of data not suitable for meta‐analysis using methods Cochrane deem to be acceptable (see Section 3.8.3). | ||

| 2 | (a) To what extent are different case management tools or approaches implemented as intended? | Synthesise evidence that captures how different tools and approaches are being implemented in practice. | Narrative summary of all studies (qualitative and quantitative) |

| (b) What explains how different case management tools and approaches are implemented in practice? | Identify, and synthesise evidence relating to, the different implementation factors and/or moderators (Section 1.2.6) that: | Meta‐analysis of quantitative studies with experimental or stronger quasi‐experimental design. | |

| (i) influence how different tools and approaches are implemented on‐the‐ground; and |

Alternative synthesis of data not suitable for meta‐analysis using methods Cochrane deem to be acceptable (see Section 3.8.3) |

||

| (ii) explain whether these tools and approaches are being implemented in the way intended/expected. | Framework synthesis of qualitative data. |

Part II: Learning from related fields

| RQ | Question | Objective | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | To what extent are different case management tools or approaches effective at countering interpersonal and collective forms of violence? | Synthesise evidence relating to different outcomes capturing the effectiveness of a tool or approach at countering violence. This analysis will examine both: | Narrative summary of evidence relating to each research question. |

| (i) Primary outcomes (i.e., measures of disengagement/desistance); and | |||

| (ii) Secondary outcomes (i.e., measures of client engagement or motivation; measures capturing attitudinal or behavioural changes relevant to primary outcomes). | |||

| 4 | (a) To what extent are different case management tools or approaches implemented as intended? | Synthesise evidence that captures how different tools and approaches are being implemented in practice. | |

| (b) What explains how different case management tools and approaches are implemented in practice? | Identify, and synthesise evidence relating to, the different implementation factors and/or moderators (Section 1.2.6) that: | ||

| (i) influence how different tools and approaches are implemented on‐the‐ground; and | |||

| (ii) explain whether these tools and approaches are being implemented in the way intended/expected. | |||

| 5 | Is there any evidence to suggest that these tools and approaches could be effective in countering radicalisation to violence? | Identify case management tools, methods and approaches used to counter other forms of violence which could potentially be adopted to counter radicalisation to violence by assessing the transferability of these interventions (see Section 4.8.2) |

Whilst there are synergies between the objectives of Part I and Part II of the review, there are important methodological differences. It is therefore necessary to outline the methodologies for each part separately. To this end, Section 3 outlines the methodology for identifying and analysing primary research studies examining the different case management tools and approaches used to counter radicalisation, before Section 4 outlines the methodology for an ‘overview of reviews’ (Pollock et al., 2021) from the broader field of violence prevention.

3. METHODOLOGY—PART I

3.1. Criteria for including and excluding studies

The inclusion criteria for research relating to questions 1 and 2 are comparable in terms of the specific problem (i.e., radicalisation to violence) and the type of intervention (i.e., case management) that will be analysed across both questions. However, as each question focuses on a different types of data (i.e., effectiveness vs. implementation), they will require separate inclusion criteria relating to the comparator conditions (i.e., research designs) and outcome measures that are relevant. This section will therefore first discuss the specific outcome measures and research designs that will be included in the analysis relating to each question, before discussing criteria that will be applied across Part I of the review as a whole.

3.1.1. Outcomes

Outcomes relevant to countering radicalisation to violence (Question 1)

Effectiveness will be evaluated by reviewing research that reports on case management interventions (and related tools or approaches) with primary and secondary client‐level outcome measures relating to countering radicalisation to violence. To be included in Part I of the review, studies must report on the below primary and/or secondary outcomes:

-

–

Primary outcomes will include measures of disengagement, desistance or deradicalisation captured using, for example, risk assessment tools; arrest or prosecutions data; case notes; and qualitative or quantitative data relating to recidivism.2

-

–Secondary outcomes will include data on the impacts that specific tools or approaches have on client participation/engagement with interventions (see Netto et al., 2014). A particularly important metric will be an intervention's rate of attrition, as attrition is a known issue when evaluating interventions seeking to counter radicalisation to violence (Williams, 2021). Secondary outcomes will also include data relating to risk and/or protective factors believed to be relevant to engagement in/disengagement from violent extremism, including background, attitudinal; psychological, experiential; and criminogenic factors (Wolfowicz et al., 2021). Whilst this list is not exhaustive, a range of relevant measures can be identified from risk assessment tools including:

-

○Extremism Risk Guidance 22+ (ERG 22+): Assesses risk using measures relating to three domains: engagement with a group, cause or ideology; intent to cause harm; and capability to cause harm (Lloyd & Dean, 2015).

-

○Violent Extremism Risk Assessment Version 2 Revised (VERA‐2R): Assesses risk against beliefs, attitudes, and ideology; history, action and capacity; commitment and motivation; protective/risk mitigating indicators; and criminal history, personal history, and mental disorder (Pressman, 2009).

-

○Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol (TRAP‐18): Assesses risk across proximal warning behaviours; and distal characteristics (Meloy et al., 2015).

-

○

Evidence for the effectiveness of an intervention in delivering such outcomes may be captured in different ways. For example, client‐level impact may be assessed using tools that capture whether specific risk factors have been successfully eliminated and/or specific protective factors have been successfully developed. However, other interventions may use tools to assess a client's ‘distance travelled’ towards positive outcomes (e.g., Romaniuk & Davies, 2017).

Outcomes relevant to implementation (Question 2)

The process of implementation will be evaluated by reviewing evidence relating to how different tools and approaches are being used, adopted and understood in practice, and whether they are being used in ways that are consistent with their internal logic and any principles of best practice that have been developed. For example, are risk assessment tools used to inform case planning? Do case plans reflect the results of risk assessments? Are the intervention plans implemented in ways that are consistent with the original case plans/risk assessments? A non‐exhaustive list of potential outcomes might include those captured by process evaluations and other types of study exploring how closely the implementation of tools or approaches mirror their underlying logic. This might include examinations of whether practitioners working within RNR approaches are sensitive to all three elements of the RNR approach (Viljoen et al., 2018), and whether specific tools and approaches enable case managers to more effectively and/or efficiently match intervention components to risks and needs (College of Policing, 2021b); evidence of how specific tools, methods and procedures are used in practice (e.g., Salman & Gill, 2020), such as how different tools are used together; and levels of compliance with case management tools in practice (Schaefer & Williamson, 2018). Data relevant to the various factors that contribute to how tools and approaches are being implemented (i.e., Question 2b) will be drawn from studies discussing those implementation factors and moderator factors outlined in Section 1.2.6 above. It might also include outcome data from studies capturing practitioner or client feedback relating to, for example, whether tools or approaches require any adaptation (e.g., Salman & Gill, 2020).

3.1.2. Types of study design

Evaluating effectiveness at countering radicalisation to violence (Question 1)

Only quantitative studies using experimental (e.g., randomised controlled trials) or ‘stronger’ quasi‐experimental research designs (as listed in guidance such as the UK government's Magenta Book (HM Treasury, 2020) will be eligible for inclusion in the analysis of question 1. Following previous Campbell systematic reviews relating to counter‐radicalisation (e.g., Mazerolle et al., 2021) and the Magenta Book, eligible quasi‐experimental designs include:

-

–

Cross‐over designs;

-

–

Regression discontinuity designs;

-

–

Designs using multivariate controls (e.g., multiple regression);

-

–

Matched control group designs;

-

–

Unmatched control group designs where the control group has face validity;

-

–

Unmatched control group designs allowing for difference‐in‐difference analysis; and

-

–

Time‐series designs.

Whilst these quasi‐experimental designs are considered less robust than experimental research designs, they are increasingly being cited as potential solutions to long‐standing and well‐documented evaluation challenges in the field of counter‐radicalisation (Braddock, 2020). For both quasi‐experimental and experimental designs, eligible comparator/control group conditions will include treatment‐as‐usual; no treatment; and alternative treatment.

Data drawn from studies using experimental designs will be analysed separately to data drawn from studies using quasi‐experimental designs. Qualitative research will not be included.

Evaluating implementation (Question 2)

Both quantitative and qualitative research will be included when analysing how case management tools and approaches are being implemented in practice (Q2a); and those factors that influence whether tools and approaches are implemented as‐intended/expected (Q2b).

Quantitative research

Where relevant, experimental and those stronger quasi‐experimental designs outlined above will be included in the analysis of Question 2. However, as this question is focused on assessing the process of implementation, and not on evaluating impact, quantitative studies with weaker quasi‐experimental or non‐experimental designs will also be included in this analysis.

Only evidence relating to implementation from quantitative studies with ‘stronger’ research designs (e.g., experimental or stronger quasi‐experimental) designs will be included in the meta‐analysis for question 2. Quantitative studies with weaker studies will only be included in the qualitative analysis as outlined in the data analysis section later in the protocol.

Qualitative research

Qualitative and mixed‐methods research will be included in our analysis for question 2, with qualitative and quantitative data analysed separately. Qualitative data is crucial for understanding how practitioners are using tools such as the ERG 22+ to monitor client progress and outcomes (Salman & Gill, 2020); for capturing how case management interventions are delivered on the ground (e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2021a); and, as argued by Higginson et al. in their systematic review of gang‐related interventions, for capturing ‘the broadest range of evidence that assesses the reasons for implementation success or failure’ (Higginson et al., 2015, p. 22). Qualitative data is also needed to capture sources of additional data (including qualitative assessments) that case managers may use to supplement formalised measurement tools when assessing client progress (Lloyd, 2019). Studies drawing on qualitative interviews will also be crucial for capturing implementation data such as practitioner feedback on different tools and approaches (e.g., Chantraine & Scheer, 2021).

3.1.3. Treatment of qualitative research

As discussed above qualitative research will be included when assessing processes of implementation (i.e., Research Questions 2a and 2b). However, qualitative data will be examined separately to quantitative data (see Data Analysis section) and will not be included in any meta‐analysis (i.e., qualitative data will not be converted into quantitative metrics).

3.1.4. Publication types

Both peer‐reviewed and non‐peer‐reviewed/grey literature studies will be included.

3.1.5. Types of intervention

Part I of the review will examine studies that report on case management interventions, and their associated tools and approaches, seeking to counter radicalisation to violence. This will include ‘standalone’ case management interventions, as well as programmes in which case management is one of many components being used to tackle radicalisation to violence.

To be included in Part I of the review, studies must report on primary research which concentrates on case management interventions and/or components of case management interventions (e.g., risk assessment, case planning etc.) with the aim of countering radicalisation to violence. Interventions must meet two inclusion criteria:

-

1.

They must focus on individual clients (and not communities or collectives) and meet the definition of a case management intervention outlined above (i.e., incorporate the specific elements of case management listed above).3

-

2.

They should be designed to counter radicalisation to violence. Interventions must seek to prevent at‐risk individuals from engaging in violent extremism and/or promote the disengagement of those who are already engaged in violent extremism (i.e., secondary and tertiary interventions). Where possible, this review will also examine evidence relating to how ‘at risk’ individuals are assessed as being eligible for an intervention, as well as the specific measures used to assess an individual's progress and outcomes. This review excludes primary interventions as they are focused on delivering client‐level outcomes whose relationship to violence is often less explicit (Marsden et al., 2017).

These inclusion criteria have been designed to ensure that Part I of the review is able to capture evidence from studies that report on case management interventions in their entirety, and those exploring the delivery and/or effects of individual components of the case management process. Examples of this type of research might include primary research studies that:

-

–

Examine the implementation or impact of violent extremism risk assessment tools. Studies examining a) how practitioners use tools to assess clients, develop intervention plans or monitor and evaluate client progress and outcomes (e.g., Chantraine & Scheer, 2021; Salman & Gill, 2020) or b) the effects tools have on preventing negative outcomes (e.g., Viljoen et al., 2018) will be included. Studies examining the psychometric properties of tools will be excluded as that literature is the subject of a separate Campbell review (Hassan et al., 2022).

-

–