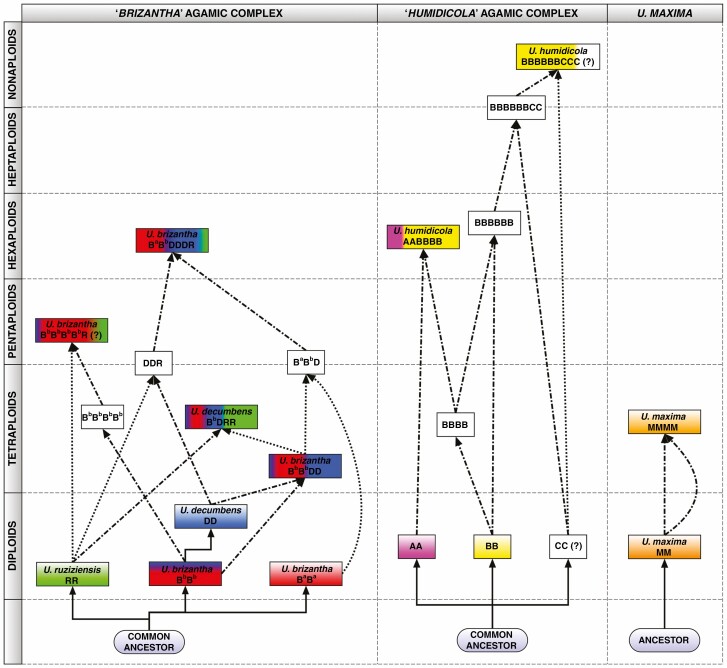

Fig. 8.

A model for the evolutionary origin of Urochloa species in the ‘brizantha’ (left) and ‘humidicola’ (middle) complexes, and in U. maxima (right), built from this study and published data: genome sizes and ploidy (Supplementary Data Table S1); repetitive DNA sequences from whole genome sequence analysis (k-mer counts and graph-based clustering; Supplementary Data Tables S3 and S4); in situ hybridization with defined repeat probes (Figs 5 and 6) and genomic DNA (Fig. 4; and Corrêa et al., 2020); karyotype analyses (Corrêa et al., 2020); meiotic behaviour (Risso-Pascotto et al., 2005; Mendes-Bonato et al., 2007; Fuzinatto et al., 2007); chloroplast genome (Pessoa-Filho et al., 2017); hybrid occurrence (Table 1; Mendes et al., 2006; Vigna et al., 2016; Risso-Pascotto et al., 2005); CIAT breeding programmes (Renvoize and Maass, 1993; Miles et al., 1996); and reported apomixis (Roche et al., 2001). The three line types show evolutionary sequence divergence (solid line), and hybridization events involving haploid, n (dotted line), or unreduced, 2n (dash-dotted line), gametes from different genomes (designated in Fig. 7). White blocks: putative species/hybrids.