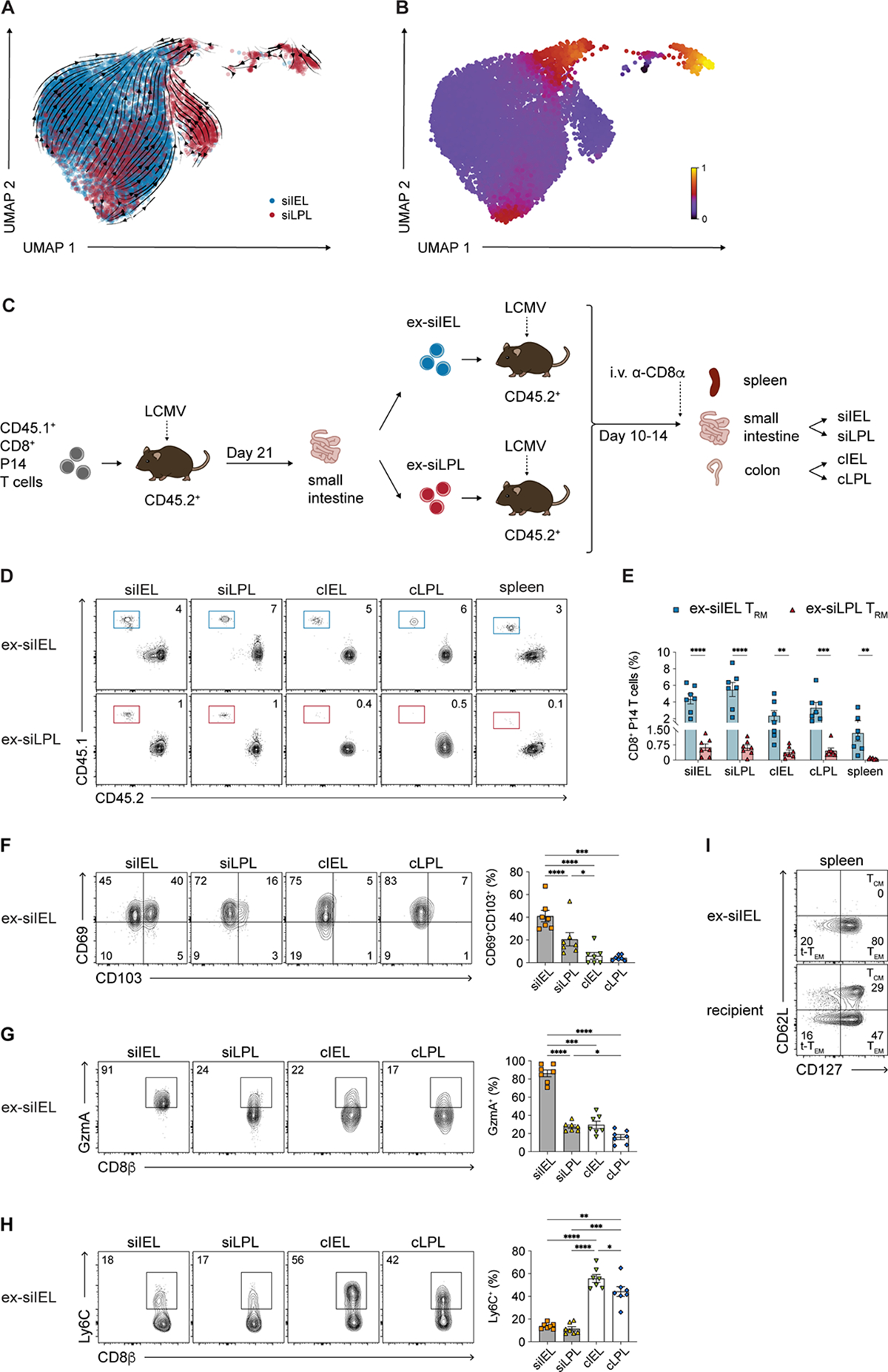

Figure 4. Small intestine IEL TRM cells may exhibit higher developmental plasticity than siLPL TRM cells.

(A and B) Velocities (A) and latent time (B) of siIEL and siLPL TRM cells derived from scVelo projected onto a UMAP-based embedding.

(C) Experimental design. siIEL and siLPL TRM cells were FACS-purified from CD45.2+ recipient mice ≥21 days following adoptive transfer of donor CD45.1+ P14 T cells and LCMV infection. Cells were transferred into new, separate CD45.2+ recipients subsequently infected with LCMV and sacrificed 10–14 days later.

(D and E) Representative flow cytometry plots (D) and bar graphs (E) showing frequencies of transferred CD45.1+ ex-siIEL (left) or CD45.1+ ex-siLPL (right) TRM cells in the intestinal tissue compartments and spleen.

(F–H) Representative flow cytometry plots (left) and bar graphs (right) showing frequencies of cells expressing CD69 and CD103 (F), GzmA (G), or Ly6C (H) among ex-siIEL TRM cells in the intestinal tissue compartments.

(I) Representative flow cytometry plots showing expression of CD62L and CD127 among ex-siIEL CD8+CD45.1+ P14 T cells or recipient (non-P14) CD8+CD45.2+ T cells in the spleen.

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Repeated measures one-way ANOVA. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 ****p<0.0001. Data are representative of ≥2 independent experiments with n=5–6 mice per experiment.