Abstract

Introduction Music is commonly played in operating rooms. Because microsurgery demands utmost concentration and precise motor control, we conducted the present study to investigate a potentially beneficial impact of music on performing a microsurgical anastomosis.

Materials and Methods We included a novice group (15 inexperienced medical students) and a professional group (15 experienced microsurgeons) in our study. Simple randomization was performed to allocate participants to the music-playing first or music-playing second cohort. Each participant performed two end-to-end anastomoses on a chicken thigh model. Participant demographics, their subjective preference for work environment (music/no music), and time to completion were noted. The performance of the participants was assessed using the Stanford Microsurgery and Resident Training (SMaRT) scale by an independent examiner, and the final anastomoses were evaluated according to the anastomosis lapse index.

Results Listening to music had no significant effect on time to completion, SMaRT scale, and anastomosis lapse index scores in both novice and professional cohorts. However, the subjective preference to work while listening to music correlated with high SMaRT scale scores within the professional cohort ( p = 0.044).

Conclusion Playing their preferred music in the operating room improves the performance scores of surgeons, but only if they subjectively appreciate working with background music.

Keywords: arterial anastomosis, microsurgery, music, surgical education

Introduction

Many surgeons prefer to listen to music while performing surgeries. Ullmann et al reported that the operating room staff, including both operating room nurses and surgeons, listen to music on a regular basis. Moreover, 79% of the survey participants claimed that it makes them feel calmer and more efficient. 1 Some studies investigated the effect of music based on objective parameters with largely positive results. According to these studies, listening to favorite music can lead to lower autonomic reactivity as evaluated by measuring blood pressure, pulse, and skin conductance during surgical tasks. 2 3 Moreover, Lies and Zhang showed that listening to preferred music reduces repair time and significantly improves the quality of repair while performing a layered wound closure on pig feet. 4 However, some studies also suggest that music can impair communication and lead to distraction, especially among the nonsurgical staff. 3 5 With respect to microsurgical tasks, the literature provides only one study, which reports that music improves the instrument motion. These results were based on data acquired by video recording participants while performing arterial anastomoses and assessed using motion analysis software. 6

Because the current literature addresses only motion analysis as an outcome criterion, in the present study, we aim to examine the potential effects of music on performing a microsurgical end-to-end anastomosis by evaluating both performance parameters of the participants and final quality of the anastomosis. In addition, we investigate not only the effect of music on skilled surgeons but also its effect on inexperienced medical students, who are at the beginning of the microsurgical learning curve.

Materials and Methods

The present study consisted of two cohorts, each of which consisted of 15 participants, who were asked to perform arterial anastomoses on chicken femoral arteries. Chicken thighs were chosen because chicken femoral arteries are similar to human distal arteries in terms of wall thickness, diameter, and histological properties.

The first cohort comprised 15 microsurgical novices. A free microsurgical training day was offered at a local medical school. No further information regarding the study was provided. Fifteen students were asked to bring earphones and a device that is able to play their favorite music to the microsurgical training center. Prior to initiation, all participants expressed verbal consent to attend a microsurgical survey, but they were not informed of the purpose of the study. Moreover, all students had to confirm that they had never received any microsurgical training. Students were randomly assigned to a numbered workstation. Moreover, the participants' demographics (age and sex) and favorite type of music were noted. Each workstation was equipped with a stationary Zeiss microscope, a standard microsurgical set, and 9–0 nylon sutures.

The lead author gave a detailed introduction to microsurgery focusing on the correct handling of the instruments and end-to-end anastomosis suturing techniques. Femoral arteries were dissected, and after placing the approximator on the intact blood vessel, it was cut. This represented our starting position for the first stitch of every arterial repair. Each participant performed an arterial anastomosis on a trial basis while the authors, who served as proctors, could simultaneously assist and answer any questions.

In the second step, students received another chicken thigh, which was marked with a random number to blind the evaluation of the anastomoses. The participants were simply randomized according to their seating position—the participants with odd numbers were assigned to perform the anastomosis with their favorite music playing on their earphones and those with even numbers were instructed to only insert their earphones into their ears (without playing music) to avoid optical bias. The students were asked to start performing the first suture simultaneously and notify the authors upon completion. After everyone completed this anastomosis, they received one more chicken thigh, which was also marked with a random number. The students repeated the task in an exactly identical manner as the previous procedure but with the music either turned on or off in the opposite manner than during the previous anastomosis. Upon completion of both anastomoses, the participants were asked whether they subjectively preferred to work with or without music. During these steps, no furthers assistance was given by the tutors.

Time taken to complete the anastomosis procedures was recorded with a stopwatch. An independent examiner, who also listened to music to avoid any acoustic bias, assessed the student's work performance using the Stanford Microsurgery and Resident Training (SMaRT) scale (9–45 points). 7 This scale consists of nine categories graded on a 5-point Likert scale, in which 1 equals “failure” and 5 is “superior performance”: instrument handling, respect for tissue, efficiency, suture handling, suturing technique, quality of knot, final product, operation flow, and overall performance. 7 The key regarding which preparation belonged to which participant was known only to the first co-author, which helped to blind the study. Next, all chicken thighs were presented to a blinded examiner, who cut the anastomoses open and assessed them according to 10 errors published by Ghanem et al, that is, disruptions of the anastomosis line, back wall catches, oblique stitches that cause distortion, wide bites causing tissue enfoldment, partial thickness stitches, vessel tears or cheese wiring, a large interstitch gap, tight stitches causing tissue strangulation, suture thread protrusion in lumen, and large edge overlaps. 8 Finally, the anastomosis lapse index (ALI) score is calculated by summing up all occurring errors in each anastomosis. 8

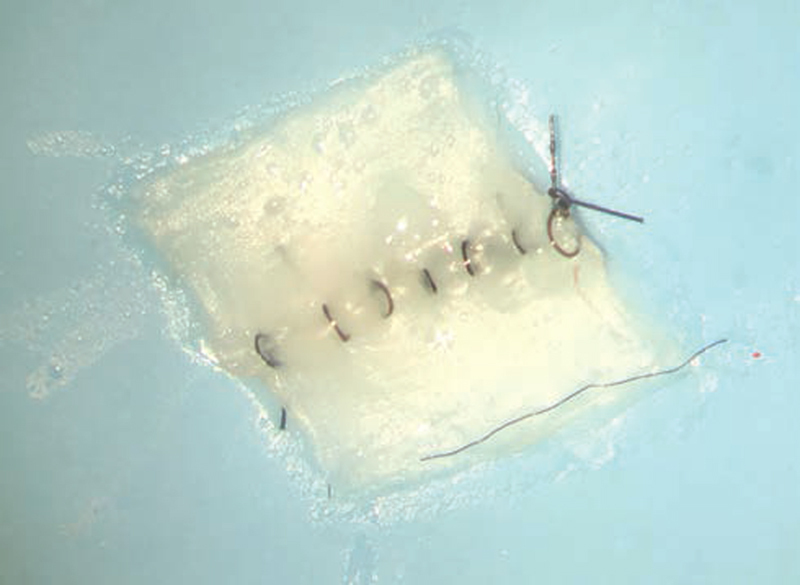

The second cohort consisted of 15 microsurgery professionals (orthopedic and plastic surgery residents and senior physicians). Apart from excluding the introduction to microsurgery, we exactly adhered to the study protocol as described above—the participants could perform an anastomosis on a trial basis. Subsequently, the cohort was divided into two groups (with and without music) for their first assessed vascular suture. Next, the group that was allowed to listen to music first was assigned in the opposite manner for performing their second evaluated anastomosis. Time taken to complete the procedures was recorded, and an independent examiner assessed the performance using the SMaRT scale. Anastomoses were separately graded by a blinded independent examiner using the ALI score ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Intimal view of a longitudinally cut anastomosis assessed with 0 anastomosis lapse index points, representing a perfect anastomosis.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (± standard deviation) or median (range (minimum–maximum)) in case of non-normal data. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS by IBM (Version 24). Paired Student's t -tests were used to compare completion times, SMaRT scale scores, and ALI scores of anastomoses made with and without music. The potential correlation between the participant's subjective preference to work with or without music and ALI scores, SMaRT scale scores, or times of repair was estimated by binary logistic regression analysis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In the novice cohort ( n = 15), eight women and seven men were included. The mean age was 23 years and 11 months (22–27 years). Genres of music preferred by the medical students included chart music ( n = 5), alternative music, classical, sleep playlist, hip-hop, instrumental music, lounge music, metal, party music, and rhythm and blues ( n = 1 for each). Regarding the subjective preference assessment after performing all anastomoses, four students preferred to work in silence, and 11 enjoyed working with music ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Demographics and subjective preference of study participants.

| Novices | Professionals | |

|---|---|---|

| Women/men | 8/7 | 2/13 |

| Age (y) | 23.9 (22–27) | 34.4 (26–54) |

| Subjective preference (with music/without music) | 11/4 | 7/8 |

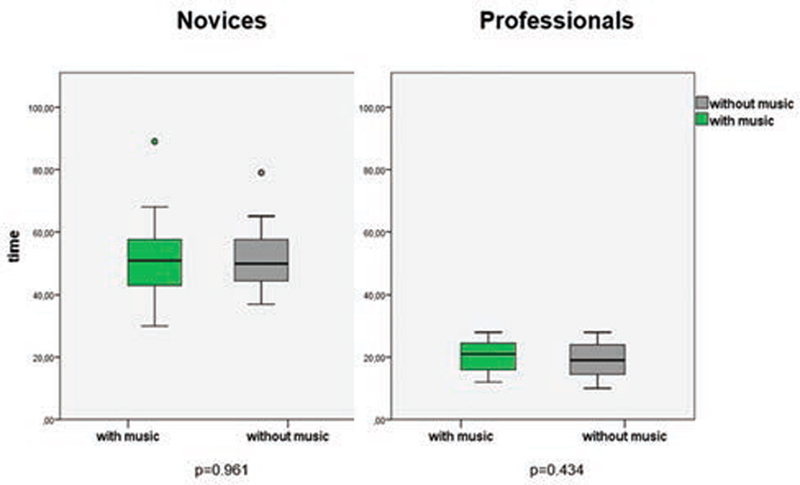

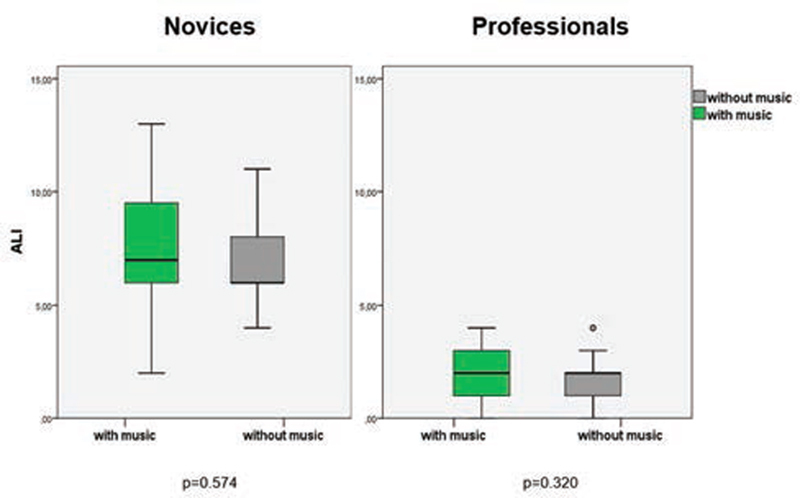

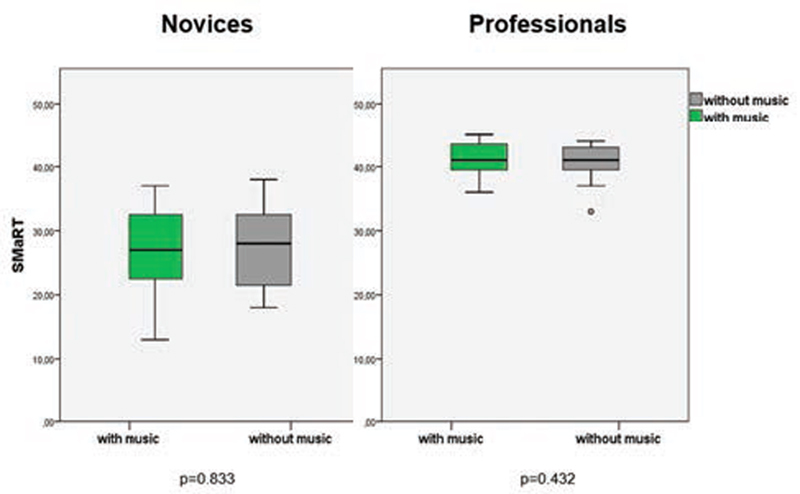

All outcome parameters indicated no significant difference between performing with or without music. The average time to perform an anastomosis was 51.8 minutes (±11.3) without music and 52.1 minutes (±14.3) with music ( p = 0.961) ( Fig. 2 ). The mean ALI score was 7.1 (±2.2) without music, whereas that with music was 7.5 (±3.0) ( p = 0.574) ( Fig. 3 ). With respect to performance scores, mean SMaRT scale score for participants working in silence was 27.5 (±6.6), whereas that of participants working while listening to music was 27.1 (±7.0) ( Fig. 4 ). The student's subjective preference whether they liked to work with or without music did not correlate with any outcome parameter ( p > 0.5).

Fig. 2.

Time to complete the task among novices and professionals with and without music.

Fig. 3.

Anastomosis lapse index scores of novices and professionals with and without music.

Fig. 4.

Stanford Microsurgery and Resident Training scale scores of novices and professionals with and without music.

Our professional cohort consisted of nine orthopedic surgery residents, two plastic surgery residents, three orthopedic surgery senior physicians, and one aesthetic surgery senior physician. All participants received microsurgical training during their residency and regularly perform microsurgical procedures on real-life patients in the operating room. There were three female and 12 male participants with a median age of 34.4 years (26–54 years). The preferred music genres also showed a wide range, including rock music ( n = 5), alternative rock music ( n = 2), classical, electronic music, hip-hop, house music, Italian hit songs, jazz music, reggae, and techno ( n = 1 for each). With respect to the subjective preference assessment, eight participants preferred to work without music, whereas seven professionals preferably worked with music ( Table 1 ).

While comparing the outcome parameters of anastomoses sutured with and without music, we could not detect any significant difference either. The average time to finish an anastomosis was 19.3 minutes (±5.5) without music and 20.3 minutes (±5.4) with music ( p = 0.434) ( Fig. 2 ). In terms of anastomoses quality, the ALI score for participants working in silence was 1.7 (±1.3) and that for participants working while listening to favorite music was 2.1 (±1.3) ( p = 0.320) ( Fig. 3 ). The mean SMaRT scale score for participants working without music was 40.6 (±3.0), whereas that for participants working with music was 41.1 (±2.9) ( p = 0.432) ( Fig. 4 ).

The binary logistic regression analysis revealed a statistically significant correlation between the subjective preference of the participants for background music and high SMaRT scale scores ( p = 0.044).

Discussion

Performing an end-to-end anastomosis demands extraordinary concentration and precise motor control from a microsurgeon. Any tool or factor that can potentially improve these attributes has a considerable effect. In sports, this concept is called the “aggregation of marginal goals,” which refers to the search for a tiny margin of improvement in every single aspect of a task such that all small adjustments accumulate to a remarkable overall performance. Accordingly, it can be adopted for microsurgery because every single improved sub-element related to this high-precision task can result in more persistent surgeons, shorter operation times, and higher quality anastomoses. With respect to this aspect, the literature reveals that better surgical dexterity can be reached by oral intake of a low dose of propranolol and by avoiding caffeine, fasting, or sleep deprivation prior to surgical procedures. 9 10 11 12

Focusing on the effect of music on humans, a correlation between music and the autonomous system has been previously detected. Studies have shown that music can lower the heart rate and blood pressure of patients. 13 14 15

Although music is commonly played in operating rooms, there are limited data available on its effects on surgeons. Because there is especially a lack of research investigating the effect on microsurgeons, we believed it was essential to conduct this study.

Our investigations suggest that music, in general, does not improve microsurgical skills and performance, but the subjective preference to work with favorite music or in silence represents the crucial point. Thus, we showed that the microsurgical professionals in our study who stated that they preferred to work with music showed a significantly better performance on the SMaRT scale with music than without music. Conversely, participants who appreciated operating in silence showed a worse performance with background music than without background music. Our findings are corroborated by a study by Miskovic et al, who showed that participants inexperienced in laparoscopic procedures performed better and faster while listening to music only if they considered the music pleasant. 16 There is only one study available in the medical literature that focuses on the correlation between music and microsurgery. Shakir et al evaluated the effect of music on performing end-to-end anastomoses by using a motion tracking system and motion analysis software. Contrary to our results, they conclude that preferred music, in general, is a beneficial factor in the operating room, without taking into account whether the participants preferred to work with music or not. 6 Some studies also reported adverse effects of music, for example, impaired communication or distracted attention; however, the effects were studied only in nonsurgical staff (anesthetists or surgical nurses). 2 3 5 17

Our results also suggest that music had no effect on our novice cohort. We hypothesize that music neither improved performance nor distracted the medical students in our study because performing an end-to-end anastomosis represents a complex and highly demanding task, which requires all their attention on visual aspects and motion sequences. Thus, we suggest that the principle of aggregation of marginal goals is only applicable if microsurgery novices have already reached a basic skill level. After having gained rudimentary muscle memory, some minor aspects such as background music can affect performance. These findings are corroborated by results from Lies and Zhang who reported that music had negligible effects on their most unexperienced study participants. 4 Moreover, the novice cohort in our study revealed a broad scattering of all three outcome parameters, and therefore, we deduce that medical students with no previous experience in microsurgery exhibit a wide range of aptitude in this surgical specialty.

The present study also has some limitations. First, it is very challenging to recreate the real-time environment of an operating room. We acknowledge that listening to a personal playlist with earphones at an individual volume is rather unusual in an operating room setting. Nevertheless, this has to be done to blind the SMaRT scale assessment and to allow all participants to listen to their personal favorite music. In addition, the SMaRT scale and ALI score assessments remain subjective parameters, although we had implemented several measures to avoid any potential bias. Furthermore, the order in which anastomoses are performed (with or without music first) has potential effects on the results. Therefore, we introduced an arterial repair on a trial basis for both cohorts, such that even the professionals could warm up and become acquainted with the study setting, equipment, and preparations. Further studies including a high number of participants consisting of various occupational groups in the operating room, that is, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and the nursing staff, would be beneficial to gain deeper insights in the effect of music in this demanding work environment. Moreover, the impact of nonpreferred music could also be of interest because a certain playlist, which is mostly chosen by one single person, affects the whole operating room staff regardless of whether each individual appreciates listening to this type of music or not.

Finally, our study provides supporting evidence for playing music in the operating room if the surgeon prefers listening to music while operating. We expect that this study would encourage more research on this controversial topic.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that music in the operating room can enhance the performance of surgeons in a microsurgical end-to-end anastomosis, but only if they subjectively prefer to work while listening to their favorite music. In addition, music has no effect on microsurgery novices.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Ullmann Y, Fodor L, Schwarzberg I, Carmi N, Ullmann A, Ramon Y. The sounds of music in the operating room. Injury. 2008;39(05):592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen K, Blascovich J. Effects of music on cardiovascular reactivity among surgeons. JAMA. 1994;272(11):882–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moris D N, Linos D. Music meets surgery: two sides to the art of “healing”. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(03):719–723. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lies S R, Zhang A Y. Prospective randomized study of the effect of music on the efficiency of surgical closures. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(07):858–863. doi: 10.1093/asj/sju161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawksworth C, Asbury A J, Millar K. Music in theatre: not so harmonious. A survey of attitudes to music played in the operating theatre. Anaesthesia. 1997;52(01):79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.t01-1-012-az012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shakir A, Chattopadhyay A, Paek L S.The effects of music on microsurgical technique and performance: a motion analysis study Ann Plast Surg 201778(05, Suppl 4):S243–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satterwhite T, Son J, Carey J et al. The Stanford Microsurgery and Resident Training (SMaRT) scale: validation of an on-line global rating scale for technical assessment. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72 01:S84–S88. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghanem A M, Al O mran, Y, Shatta B, Kim E, Myers S. Anastomosis Lapse Index (ALI): a validated end product assessment tool for simulation microsurgery training. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2016;32(03):233–241. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1568157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fargen K M, Turner R D, Spiotta A M. Factors that affect physiologic tremor and dexterity during surgery: a primer for neurosurgeons. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quan V, Alaraimi B, Elbakbak W, Bouhelal A, Patel B. Crossover study of the effect of coffee consumption on simulated laparoscopy skills. Int J Surg. 2015;14:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urso-Baiarda F, Shurey S, Grobbelaar A O. Effect of caffeine on microsurgical technical performance. Microsurgery. 2007;27(02):84–87. doi: 10.1002/micr.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humayun M U, Rader R S, Pieramici D J. Awh CC, de Juan E Jr. Quantitative measurement of the effects of caffeine and propranolol on surgeon hand tremor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(03):371–374. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150373010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byers J F, Smyth K A. Effect of a music intervention on noise annoyance, heart rate, and blood pressure in cardiac surgery patients. Am J Crit Care. 1997;6(03):183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen D, Topp R, Singer L. The effect of self-selected music during colonoscopy on anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(03):126–136. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2002.34140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallek R, Corey K, Qamar A et al. Soothing the heart with music: a feasibility study of a bedside music therapy intervention for critically ill patients in an urban hospital setting. Palliat Support Care. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951519000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miskovic D, Rosenthal R, Zingg U, Oertli D, Metzger U, Jancke L. Randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of music on the virtual reality laparoscopic learning performance of novice surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(11):2416–2420. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narayanan A, Gray A R.First, do no harmony: an examination of attitudes to music played in operating theatres N Z Med J 2018131(1480)68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]