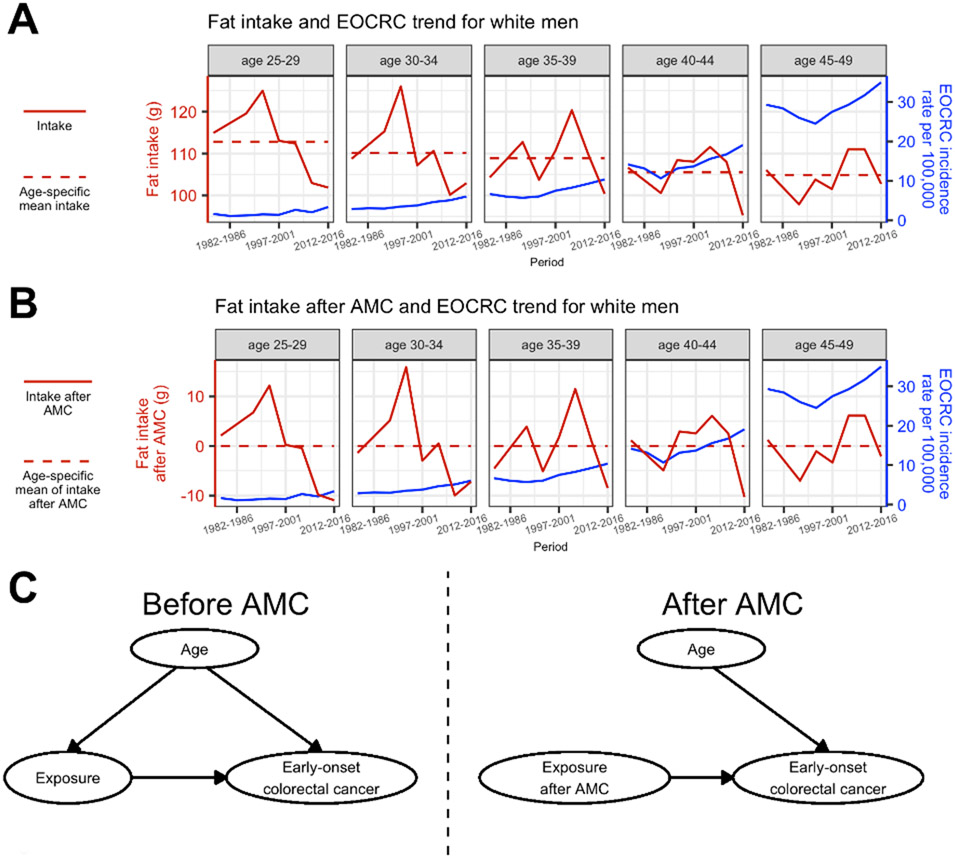

Figure 1. Schematic of the age-mean centering (AMC) approach to alleviate age confounding.

(A) Trends in fat intake and early onset colorectal cancer (EOCRC) among white men aged 25-49 show an example where both the exposure (here, fat intake) and outcome (here, EOCRC) are associated with age and could act in opposite directions, i.e., fat intake tends to decrease with age whereas EOCRC incidence tends to increase with age. (B) After removing the age-specific mean (i.e., subtracting the average of all fat intake values for that age and race group across all periods, shown by the horizontal dashed lines in A), the age-mean centered fat intake values are now on similar scales for all age groups (0 means for all age groups as shown by the horizontal dashed lines; estimated association with age: 0.00 (95% CI: −0.17, 0.17) using a regression model), whereas the trends over time remain the same as the raw data shown in A. (C) Diagrams of causal relationships before and after applying AMC to the exposure data. Without AMC, age is associated with both the exposure and outcome and could bias the estimate of exposure-outcome association (left panel). After AMC, age is no longer associated with the exposure (right panel); in addition, because changes in exposure over time (i.e., calendar years) needed to examine the changes in disease outcome over time are still retained as shown in B, the age-mean centered exposure can be used to examine the association between the exposure and disease outcome.