ABSTRACT

In light of extended stay-at-home periods during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, recent societal trends have revealed an increased use of online media to remain connected. Simultaneously, interests in at-home cooking and baking, particularly of “comfort foods” have increased. Because flour is a crucial component in many of these products, we analyze how the U.S. public, in social and online media spaces, references “flour” and its use. We also quantify the share of media mentions about flour that are devoted to flour-related food safety risks and/or risk mitigation. It was found that the volume of mentions about flour and its use fluctuate seasonally, often increasing ahead of the winter holiday season (November to December). Further, the volume of interest rapidly increased in March 2020 when stay-at-home orders were issued. The share of media devoted to flour-related food safety risks or associated illness was extremely small but generally corresponded with flour recall announcements or other public risk communications. Overall, the interest in flour and its use remains seasonal and predictably related to societal trends, such as increased baking at home during the holidays or 2020 stay-at-home orders. However, awareness of flour-related food safety risks seems largely absent on the basis of online media data collection and analysis, except in immediate reactions to flour recalls. This study suggests that more flour safety education programs may be desired to support consumers' informed decision making.

Keywords: Data analytics, Flour, Foodborne illness, Food recalls, Risk communication, Social media

Numerous foodborne illnesses are caused by food product contamination due to improper food handling practices or outbreaks identified in manufacturing facilities. Of the estimated 48 million individuals afflicted by foodborne illness every year, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die ( 9 ). One popular food product also susceptible to bacterial contamination—an ingredient often used in U.S. households—is raw flour. Raw flour is used in a variety of household cooking and baking activities but is one of a few common raw ingredients often handled freely in baking projects by children. Although flour is perceived rarely to be as risky as other raw commodities or ingredients such as meat and eggs, it can still harbor disease-causing bacteria, such as Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and Salmonella. Between 2017 and 2019, two foodborne illness outbreaks related to the consumption of flour products in the United States occurred: 21 cases of STEC and 7 cases of Salmonella ( 26 ). From January to May 2020, no outbreaks associated with flour were reported ( 11 , 12 ).

In a survey of wheat at harvest, Salmonella was found in 1.23% of samples, and E. coli was found in 0.44% of samples ( 43 ). Unfortunately, consumers are not aware of this food safety risk associated with flour ( 20 ). This lack of awareness could be attributed to the assumption that flour does not visually appear raw because it is white, very fine, and highly processed ( 4 ). Although consumers are not fully informed of flour's food safety risks, eating food with raw flour, such as cookie dough, has become commonplace in the United States. In a study analyzing risky eating behaviors of 4,343 young adults at universities, 53% self-reported consuming raw homemade cookie dough ( 7 ).

As food safety incidents continue to rise, studies have probed consumer responses to these occurrences. For example, when a food product was recalled or associated with outbreaks, consumers temporarily reduced purchases of the product but gradually returned to the product after some time. This phenomenon was observed during the following foodborne outbreaks: a 2008 tomato outbreak, a 2009 peanut butter outbreak, and a 2011 cantaloupe outbreak ( 3 ). However, the reduction of purchasing differed from case to case. Consumer responses varied even with the same food product in different food safety incidents. In the 2011 cantaloupe recall associated with Listeria, an empirical study found that consumers purchased significantly fewer cantaloupes than a similar recall associated with Salmonella the following year ( 31 ). It is unknown whether consumer perception changed as a result of the two cantaloupe recalls.

More recently, there has been an upsurge in a societal and cultural focus on home cooking and baking, especially in light of stay-at-home orders in early 2020 in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Flour was so sought after, and in such short supply, during the early weeks of the stay-at-home orders in spring 2020 that baking and flour were the focus of popular press making linkages to historic wartime shortages ( 44 ). Due to the pandemic, moreover, consumers are more cautious about safe food handling practices ( 51 ). Meanwhile, as U.S. residents spent more time at home over the pandemic, they also increasingly moved their lives online: work, school, essential services, and communication with friends and family all transitioned to virtual spaces ( 33 ). Having observed that, without knowing the risk associated with flour, consumers could be vulnerable to advice from online sources and social media, which may not always present accurate food safety recommendations ( 52 ).

The public's interests and perceptions surrounding food items, handling practices, and foodborne illness outbreaks have commonly been quantified through surveys ( 38 ), or by studying traditional journalistic outlets or news media (e.g., via platforms such as LexisNexis ( 36 )). More recently, the breadth and diversity of vast amounts of social media content produced food safety information daily on media platforms worldwide ( 19 ), which have motivated businesses, academic research institutions, and nonprofit government organizations to seek a tool to identify and collect relevant data sets to gain insight.

The recent rise in social media over the past decade creates an additional source of user-generated data on the perceptions, views, beliefs, and thoughts of the general online public. In-depth online media, Web searches, and data amassed from Internet sources have long been used in social science research. Increasingly social media data, written comments, reviews, blogs, and other media formats facilitating communication have emerged as valuable in understanding what people pay attention to and/or are engaging about ( 16 ). A multitude of database and Web search tools provide useful functions, some of which are tailored for a specific subject and/or topic, such as searching legal documents, whereas others are for more general matters, such as news articles and media. For instance, LexisNexis provides deep news archives with trusted sources for government agencies to study news coverage on policies and public campaigns and for universities to conduct economic analyses ( 54 ).

Analyses examining reactions of people to social media marketing or campaign activities on the basis of data collected through social listening are becoming prevalent in marketing and related literature ( 1 , 15., 16., 17. , 27 , 30 , 50 ). Recently, advancements of language processing technologies have improved the quality of data collection and morphological analysis, which enables more profound social media analytics, such as “social media listening.” Social media listening monitors online conversations and searches, while amassing data from multiple social media venues; for example, microblogs such as Twitter, product reviews (e.g., CNET or Consumer Reports), discussion streams, and social network comments, to extract valuable insights, such as sentiment measurement ( 20 , 47 ). There are various social listening tools developed recently, such as Brand24, Brandwatch, and NetBase to assist search, surveillance, and analytics. Influencer Marketing Hub ( 28 ) presents pros and cons of various social listening platforms in its report “Top 20 Social Media Listening Tools for 2020.”

Nonetheless, the food safety sector has not devoted much attention to this area of work in online media analytics even though timely well-managed communication, an important characteristic of communication via social media, is vital to effective crisis management related to food safety risks. Jung et al. ( 27 ) exploited social media data for outbreaks over universal food items inclusive of meat, romaine lettuce, and breakfast cereals in their research and found that social and online media mentions of foodborne illness outbreaks do track the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's initial reports overall. This research focuses on a specific food item, flour, and its related food safety issues in social media spaces, while Jung et al. ( 27 ) considers foodborne illness outbreaks on overall food items.

Online media analytics tools that incorporate traditional mass media, along with social media, can be used to understand public perceptions of flour, flour usage, and flour food safety risks. As social media has become widespread, consumers use several platforms to share information about their lives, perceptions, and behaviors. In a previous study, Twitter was used to gauge public reactions to health crises, such as the Ebola virus, Zika virus, and opioid crisis ( 24 ). Analytic tools provide insight into sentiment expressed through social media, thereby allowing qualitative data to be translated into a quantitative score ( 27 , 49 ). However, few studies analyze consumers' social media response to food safety incidents, particularly recalls and outbreaks associated with flour ( 10 ). Although Jung et al. ( 27 ) is a single exception, it investigates social media responses to overall foodborne illness outbreaks and its recalls. Analysis independently on flour may provide a different aspect, considering that flour has not been perceived to be risky as a raw ingredient compared with meats or other items ( 20 ).

This study will use an analysis of consumers' social media presence (2017 to 2020) to quantify consumer response and perception of flour in the United States. Objectives of this study are to (i) quantify and analyze online media focused on flour over time; (ii) investigate the proportion of online media about flour devoted to food safety risks and illness prevention; and (iii) determine if changes in interest in flour food safety is related to recall announcements. The findings can be used by policy makers, stakeholders, and health professionals to better inform consumers about flour safety and other food safety incidents, particularly on flour.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protocol development

The NetBase ( 42 ) platform was used for data collection in this analysis. NetBase ( 42 ) offers social media search engines and platforms and access to media content on the Web from around the world, which allows for social media analytics and social listening. Two stages of data collection were conducted in this study: (i) collecting data for a broad range of online and social media activity related to “flour” (henceforth, the general flour search) and (ii) filtering the data from the first step, thereby searching within the general flour search for posts specific to flour-related foodborne illness or food safety risks associated with flour (henceforth, the flour-related illness search). Due to the nature of the searches conducted, the flour-related illness search is necessarily a subset of the general flour search conducted.

Researchers interface with the NetBase platform by inputting inclusionary and exclusionary search terms, specific domains, and even specific authors. Inclusionary search terms are fundamental in finding search results in the form of online and social media mentions or posts that refer to flour. In the first step, search terms or key words and exclusion terms are identified to develop valid data set encompassing social media posts associated with a broad range of general flour and flour-related activities in the United States. Table 1 indicates primary search terms in the first row. A total of 21 primary search terms were included to begin data collection (Table 1). Although wheat flour was the intended search subject, the nature of online media data means that mentions of flour by the general public may reference of flour of various types and/or varying uses of flour. Then, in step 2, the subsearch was conducted to elicit search results concentrating on flour-related illness or risk, by adding additional search terms, including E. coli, Salmonella, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Six terms were used for the second step to filter the broad data for flour-related food diseases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Search terms useda

| Terms and domains pursued | Specific terms used |

|---|---|

| Primary terms for foodborne illness outbreak general search | Flour, all-purpose flour, bread flour, cake flour, pastry flour, pancake mix, whole wheat flour, Arrowhead Mills, Gold Medal, King Arthur, Pillsbury, baking, bake, raw flour, raw cookie dough, homemade bread, homemade cake, homemade cookies, homemade cookie dough, home baked, gluten-free flour |

| Terms used for filtering | E. coli, Salmonella, FDA, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Diseases and Control, ecoli |

| Exclude terms | Olympic, Trump, mask, hydroxychloroquine, gay, Olympics, winning, esketamine, RCP8.5, automotive, Ariana DiValentino, chips, run, makeup, eyeshadow, wig, costume, pollution, damage, new makeup, eye shadow, glam, baked potato, baked beans, baking soda, easy bake washer, bed bugs, baked chicken, baked mac, baked ziti, bake sale, easy bake oven, bisexual bearded, dupe your brain, smaller plates, gold medal game, oven-baked BBQ |

| Exclude domains | boards.4chan.org, steamcommunity.com, 3zba.com |

To address “exclude terms” further, “PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games” brings posts, including a term “gold medal,” a flour manufacturer's name captured in our primary search terms, Gold Medal. The posts about gold medal games, therefore, are excluded by the exclusionary term “Olympics” because they drive a large number of social media activities unrelated to flour. In addition, posts about other baked dishes, such as baked chicken, were removed because they were captured by the search terms “bake” or “baked.” Moreover, “bake” or “cake,” two of the primary search terms, captured or counted posts about the news that a baker refused to make a cake for a gay couple, which brought many social media posts around June 2018. Thus, the term “gay” was included as an exclusionary term to eliminate the large number of posts about cakes for gay weddings.

In addition to inclusionary search terms, exclusionary terms are necessary to ensure that data amassed by primary search terms is relevant to the subject matter sought. A total of 37 terms are identified and excluded by researchers for conducting more relevant searching (Table 1).

A “mention” is a sentence retrieved from a post that can be thought of as the entire document ( 42 ). On the other hand, another parameter of social media activity is called a “post.” If a blog discusses general information about flour-related food risks, the entire discussion can be considered a post. However, if any sentence in the post refers to a specific flour-borne illness outbreak or a pathogen, it would be counted as a mention. Retweets are a process in which one can quote another person's post and either add additional text or not. Retweets can be removed if amplification of the original statement or opinion is not desired or kept to capture influence of a broader issue ( 23 ). In this article, given the intent to understand the overall volume of media, they were left in the data set collected. The total number of online media posts on the basis of the two steps with search terms for the general flour search and the flour-related illness search over the period of 1 January 2017 to 31 May 2020 was collected on a weekly basis. This period was chosen because it provides adequate time for seasonality or annual factors to be experienced more than once, such as cookie-making activities during Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. Five complete months of data in 2020 were amassed to capture recent stay-home orders related to activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

By its nature, individual posts or comments and accounts in social and online media space may appear, be removed, or reinstated by the authors or the platform itself. The fluidity of social media activities makes it crucial to collect data at a single documented point in time; data were collected on 9 June 2020 with yearly granularity from 2017 to 2019. In addition, considering the recent stay-at-home orders due to COVID-19, we conducted monthly granularity for 2020 to highlight a particular movement over the COVID-19 period if any existed. This would avoid a potential issue that aggregation across time may conceal important information from the pandemic that happens but largely disappears from media quickly.

Searches across countries and in multiple languages are technically possible within the NetBase platform, but researchers do acknowledge and address limitations surrounding language interpretation, slang, shorthand, and cultural context of posts. Furthermore, although flour-associated activities and foodborne illness are worldwide, the agencies governing domestic food safety, in general, and for flour are U.S. government agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or Food Safety and Inspection Service, with jurisdiction limited to the United States (and associated issued recalls are also bounded domestically). Therefore, for this analysis, the geography for all searches was limited to the United States, inclusive of the continental United States, the United States Minor Outlying Islands, and Puerto Rico. Posts exclusively in English were retrieved and analyzed.

Data analysis

Sentiment analysis, which is a popular method for constructing a comparison of positive versus negative emotions in postings, was conducted. NetBase's natural language processing engine was used to transform qualitative information in unstructured texted posts into a quantitative value representing emotion and analyze sentiment for every subject in a sentence to determine net sentiment of individual posts.

For the sentiment analysis, net sentiment is used as a valuable measure of the feeling or attitude that people express on social media ( 19 , 34 , 40 , 47 , 55., 56., 57., 58., 59. ). This comprehensive metric allows analysis of people's satisfaction through both social and survey data ( 47 ). NetBase provides its own patented and robust natural language processing engine ( 42 ) that analyzes each subject in the sentence to identify and determine the sentiment of individual posts. For example, according to NetBase ( 42 ), the natural language processing engine categorizes terms such as “artistic,” “timely food safety message,” and “E. coli treatment” as a positive sentiment, while terms such as “low quality,” “too expensive,” “outbreak,” and “diarrhea” as a negative sentiment.

The net sentiment presented throughout this analysis is the results of total percentage of positive posts less the total percentage of negative posts, resulting in a net sentiment that ranges between −100% (completely negative) to 100% (completely positive). In addition to positive and negative posts, a third kind of emotion, neutral, is also considered and reported although not used in the calculation of the net sentiment.

To discern relationships in monthly or weekly movement of mentions and net sentiment and compare them between the general flours and the flour-related illness searches over the entire period studied, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) ( 43 ) and hypothesis tests for the coefficients were conducted to investigate movement between the number of mentions and net sentiment from each data search. This hypothesis test is built for testing if there is a positive or a negative relationship between the number of mentions and net sentiment. If r presents a positive (negative) number, there is a positive (negative) relationship. The P value is a number that describes how likely it is that the null hypothesis is true by random chance. In this hypothesis test, the null hypothesis is that there is no relationship between the number of mentions and net sentiment.

RESULTS

The data search in this analysis encompasses January 2017 to May 2020, which includes several annual events, such as Thanksgiving or Christmas, when people use flour for baking cookies or cakes. Of particular interest is the period covering the early months of 2020, when people under COVID-19 stay-at-home orders might have increased in-home activities, including home baking or cooking.

Table 2 presents the top domains and sources of search results for general flour and flour-related illness searches. “Domain” refers to a specific Web address, such as www.nbc.com, while “source” includes categories such as news, which encompasses several domains. For example, www.nbc.com is a domain that would be categorized as a news source, along with other news domains such as www.cnn.com. Twitter.com is the most popular domain, accounting for the largest proportion of sources for both data pulls. Over 82 and 93% of total time line mentions are from the domain Twitter.com for the general flour and flour-related illness searches, respectively. Around 60% of the total time line mentions can be categorized into the source of Twitter for both data searches.

TABLE 2.

Top domains and sourcesa

| Mentions | % |

|---|---|

| General flour search (n = 22,231,071) | |

| Domains (n = 13,474,640) | |

| twitter.com | 81.53 |

| instagram.com | 7.91 |

| reddit.com | 7.65 |

| community.babycenter.com | 0.91 |

| boards.4chan.org | 0.49 |

| community.myfitnesspal.com | 0.40 |

| tripadvisor.com | 0.32 |

| booking.com | 0.29 |

| boards.4channel.org | 0.28 |

| forums.somethingawful.com | 0.22 |

| Sources (n = 18,342,634) | |

| 60.04 | |

| Forums | 15.01 |

| News | 9.80 |

| Blogs | 8.91 |

| Others | 0.43 |

| Flour-related illness search (n = 90,358) | |

| Domains (n = 40,084) | |

| twitter.com | 93.25 |

| reddit.com | 4.09 |

| community.babycenter.com | 0.55 |

| instagram.com | 0.44 |

| bakingbusiness.com | 0.37 |

| foodsafetynews.com | 0.30 |

| community.qvc.com | 0.27 |

| investorshub.advfn.com | 0.25 |

| ccnmag.com | 0.24 |

| foodpoisoningbulletin.com | 0.24 |

| Sources (n = 61,103) | |

| 61.18 | |

| News | 26.18 |

| Blogs | 6.71 |

| Forums | 5.63 |

| Others | 0.31 |

From 1 January 2017 to 31 May 2020.

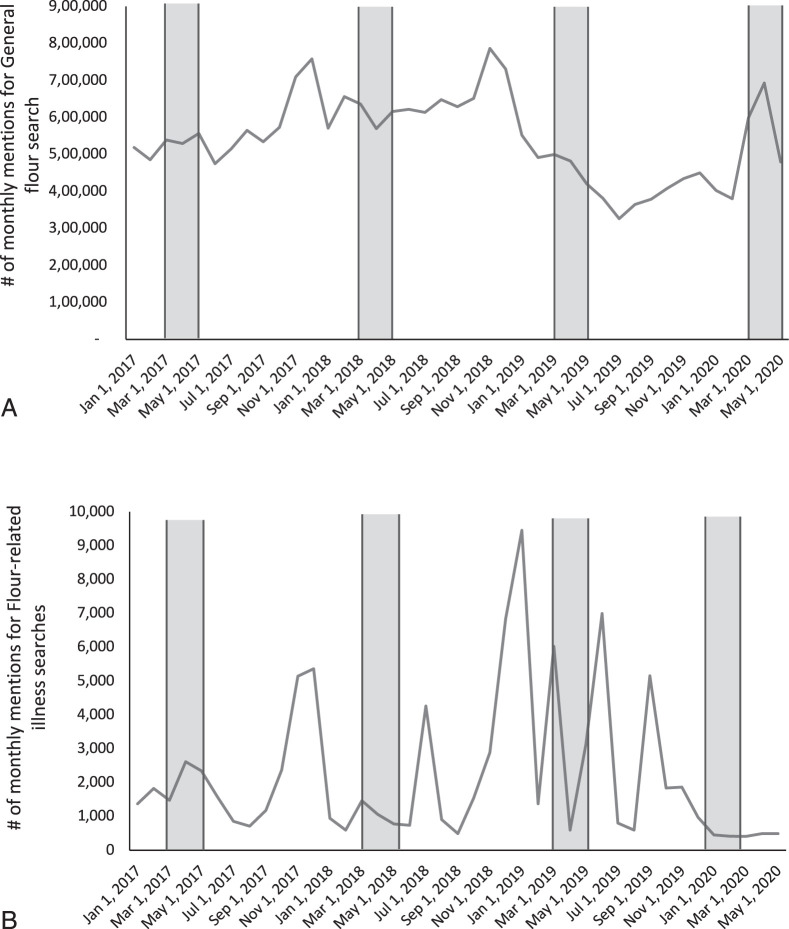

The total number of time line mentions is 22 million for the general flour search and 90,000 for the flour-related illness search. Figure 1 depicts monthly changes in mentions in the general flour and the flour-related illness searches. The total volume of mentions in the flour-related illness search increased in July 2018 and January, March, and June 2019, while they decreased over the same months in the general flour search as a whole. Likewise, mentions of general flour rose in January and November 2018 and substantially in March 2020, while the volume of search results in the flour-related illness search did not.

FIGURE 1.

Monthly changes of mentions in the general flour and the flour-related illness searches. (A) Number of monthly mentions in general flour search. (B) Number of monthly mentions in flour-related illness search.

Table 3 features popular terms, hashtags, attributes, and object mentioned. Most general mentions of flour generally (general flour search; first column) reference pleasant activities or associations. For instance, like (24%), #food (24%), great (44%), and Great British Baking Show (31%) were the top terms, hashtag, attribute, and thing mentioned, respectively. In addition, mentions related to cooking, such as recipe (16%), #recipe (16%), cute Halloween baking (9%), and baked good (23%) are present across all general flour searches. The most prominent change in volume of mentions during the period studied relates to COVID-19 in February 2020. Figure 1 visually displays that mentions soared in March 2020, which is unusual when compared with the same period from previous years (noted by shaded areas in Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Top terms, #hashtags, attributes, and things mentioned

| General flour search | % | Flour-related illness search | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terms | |||

| n = 6,127,262 | n = 111,621 | ||

| Like | 24 | Recall | 27 |

| Good | 22 | Salmonella | 24 |

| Out | 20 | Eating | 20 |

| Use | 17 | E. coli | 17 |

| Recipe | 16 | FDA | 11 |

| Hashtags | |||

| n = 964,744 | n = 2,267 | ||

| #food | 24 | #recall | 35 |

| #foodie | 23 | #foodsafety | 22 |

| #foodporn | 18 | #salmonella | 19 |

| #dessert | 18 | #ecoli | 13 |

| #recipe | 16 | #recallalert | 11 |

| Attributes | |||

| n = 89,572 | n = 6,498 | ||

| Great | 44 | Recall | 54 |

| Fresh | 23 | Afraid of get Salmonella | 19 |

| Great British Baking Show | 12 | Contaminate with bacterium | 9 |

| Easy | 12 | Bacterium | 9 |

| Cute Halloween baking | 9 | Kill bacterium | 8 |

| Things | |||

| n = 276,453 | n = 3,395 | ||

| Great British Baking Show | 31 | King Arthur flour | 29 |

| Great British Bake Off | 25 | Gold Medal flour | 22 |

| Baked good | 23 | Pillsbury flour | 20 |

| Great | 14 | Bacterium | 16 |

| No flour | 6 | Cookie | 14 |

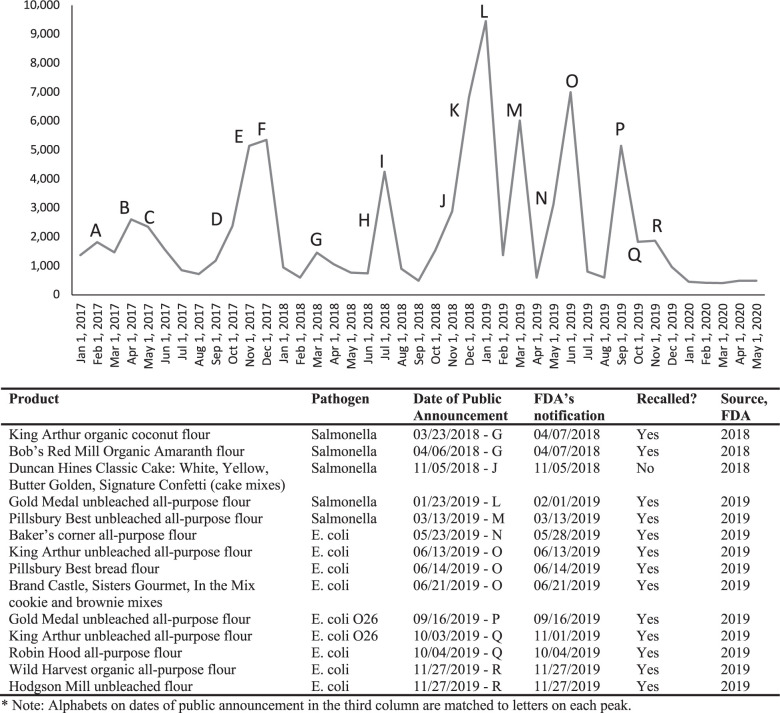

Even with the smaller data set of flour-related illness (90,000 mentions) compared with general flour (22 million mentions), search results collected in this analysis accurately reflect actual recalls or initial Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports in real time. Figure 2 illustrates peaks from the flour-related illness search and recalls for flour-related illnesses (letters G through R). Surprisingly, all the FDA's flour recalls are captured by social media reactions; this can be seen more clearly in the weekly changes in volumes of mentions. Thus, although overall awareness of flour recalls and outbreaks may be quite low, reactions do appear in online and social media spaces when recalls and illness reports are released publicly.

FIGURE 2.

Monthly changes in mention for flour-related illness search with FDA flour product recalls from 2018 to 2020.

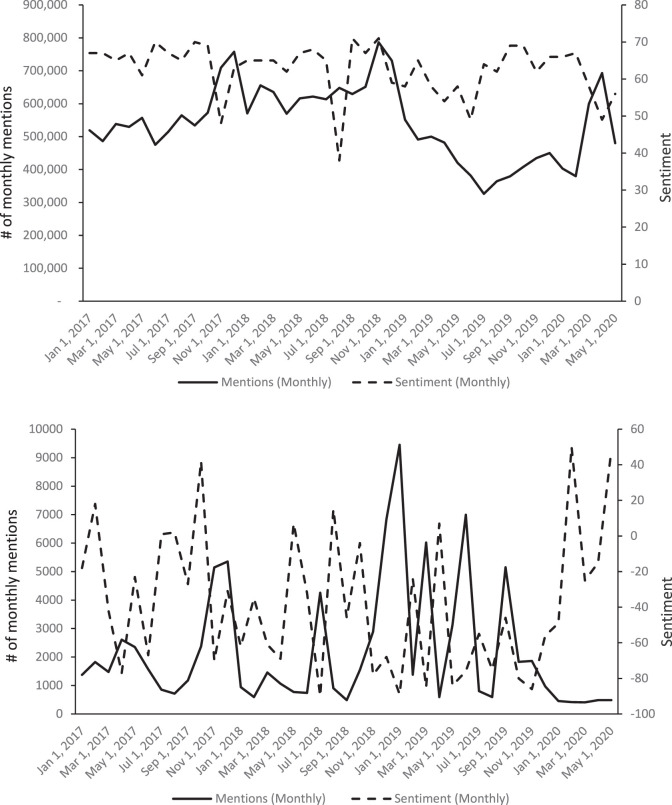

Net sentiment is an important concept in enabling researchers to link events to the corresponding online presence and/or facilitating further analysis that investigates linkages of overall sentiment and other measures of performance, such as stock prices ( 45 , 47 , 53 , 60 ). Net sentiment over time is presented graphically in Figure 3 for the general flour and flour-related illness searches. Attributes driving sentiment for the general flour and flour-related illness searches are presented in Table 4 according to whether they contributed positively or negatively. For the flour-related illness searches, it is indicated that net sentiment and mentions are mostly negatively correlated, while they are not for the general flour searches. As flour-related foodborne illnesses, just as any foodborne illness, cause acute symptoms and discomfort, the negative overall sentiment results for the flour-related illness search are expected. Figure 3 for the flour-related illness search further reveals that mentions and net sentiment move in the opposite direction.

FIGURE 3.

Monthly changes in mentions and net sentiment. (A) General flour search. (B) Flour-related illness search.

TABLE 4.

Sentiment drivers: attributes

| Search | Positive | % | Negative | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General flour | n = 166,469 | n = 40,805 | ||

| Great | 24 | Too thick | 18 | |

| Fresh | 12 | Too runny | 18 | |

| Easy | 7 | Recall | 10 | |

| Great British Baking Show | 6 | Not work | 4 | |

| Awesome baking | 5 | Expensive | 4 | |

| Great British Bake Off | 4 | Fail | 3 | |

| Make | 4 | Dip shit | 3 | |

| Flour-related illness | n = 1,173 | n = 8,899 | ||

| Kill bacterium | 43 | Recall | 38 | |

| Worth risk | 8 | Afraid of get Salmonella | 14 | |

| Safe to eat | 5 | Contaminate with bacterium | 7 | |

| Pillsbury Best Bread Flour | 4 | Bacterium | 7 | |

| Treated flour | 4 | Contaminate with E. coli | 4 | |

| Pasteurized egg | 4 | Carry risk of bacterium | 4 | |

| Worth Salmonella | 4 | Salmonella | 3 |

DISCUSSION

Domains and sources of data

A key difference between the general flour and flour-related illness searches was found for popular domains and sources beyond Twitter. For example, Instagram.com is the second most popular domain (8% of total time line mentions) for the general flour search but not for the flour-related illness search (0.4% of total time line mentions). A quarter (26%) of the mentions of flour-related illness search were from a news source, following Twitter. Only 10% of the total time line mentions for the general flour search were from news sources, which is intuitive, considering that the flour-related illness search targets words such as “E. coli,” “Salmonella,” or “FDA” by filtering within general flour search data. People are more likely to post photos of attractive cookies and cakes, homemade or purchased, on Instagram rather than photos featuring foodborne illnesses. In other words, illnesses caused by foodborne pathogens are generally reported in news, whereas an individual's positive associations with baking, cooking, or other uses of flour are usually inherently not newsworthy.

Mentions about flour

Movement of mentions within data sets and over time varied between the general flour search and the flour-related illness search. The rapid increase in March 2020 mentions volume may be related to COVID-19; top words during this month concern in-home cooking or baking activities related to flour, such as baking cookies and cakes. Interestingly, such words as “home baking” and “cooking” are captured within posts also mentioning the top term “quarantine” over a week from 15 March to 22 March 2020. For example, “[B]eing in quarantine has helped her appreciate the little things in life and give her a lot of quality family time. . . . We've had the pleasure of some quality family time, lots of home baking and cooking.” Another top term during this week in March 2020 was “Netflix” from a post “Netflix or other streaming services . . . by watching the old movies you loved from your childhood.” With COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, fun home activities beyond cooking, such as playing games and virtual meetings increased, captured by this example: “Play board games, . . . and let children use apps like Zoom or Skype so they can stay in touch with their friends.”

Mentions about flour food safety risks

The flour-related illnesses search resulted in a much smaller data set with fewer total mentions: 22 million for general flour versus 90,000 for flour-related illness. This may be due to an unawareness of foodborne illness related to flour and/or unwillingness to share publicly about the resulting illness, especially when compared with a willingness to share baking photos or accomplishments. According to Feng and Archila ( 17 ), 85% of flour consumers were unaware of flour recalls or outbreaks, and 66% said they had eaten raw cookie dough or batter. Only 17% believed they would be affected by flour recalls or outbreaks.

The smaller number of negative mentions of flour could also be caused by consumers' low-risk perceptions of flour. Historically, consumers have not considered low-moisture foods to be high risk for foodborne pathogens. A previous consumer survey showed that 85% of flour users had never heard of foodborne outbreaks or recalls associated with wheat flour ( 17 ). This phenomenon was also reported in other consumer surveys associated with low-moisture foods. For example, only one-tenth of consumers believed people could contract foodborne illness from eating sesame seed products ( 23 , 35 ). Further, less than a quarter of pet owners considered dry pet foods as a potential source of foodborne pathogens ( 50 ).

Although it is small, reactions clearly track all the FDA's recalls or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's initial reports for flour (Fig. 2). Each peak in Figure 2, however, has a different number or volume of attention garnered. For example, a January 2019 recall of General Mills' Gold Medal all-purpose flour drew the most attention and the largest number of mentions. On the other hand, a smaller volume of mentions was measured congruent to a November 2019 recall of King Arthur all-purpose flour by the FDA. Considering the King Arthur recall happened around the Thanksgiving holiday in November when people usually enjoy activities, such as baking cookies and sweets at home, the smaller number of mentions for the King Arthur recalls than most of other recalls seems counterintuitive.

The clear matching of terms in the swell of media coverage devoted to flour food safety accompanying a recall or illness announcement is an interesting finding of this analysis. A previous study analyzed 1.8 million tweets to explore the extent to which news coverage and influential actors can explain peaks in Twitter activity ( 2 ). The findings show that the news values social impact, geographical closeness, facticity, as well as certain influential actors, and can explain peaks in volume of mentions. Similarly, there could be many factors that attribute to peaks from the flour-related illness search. Those factors and the varying degrees of the peaks observed are worthy of further investigation.

Other peaks in volume of mentions do not originate from recalls but from general information or warning messages about flour-borne illnesses. For these peaks (letters A through F) in Figure 2, postings mostly concern the FDA's warning against eating raw dough. For example, “From December 2015 to September 2016, there were 56 cases of E. coli–related illnesses reported across the US related to the consumption of raw flour,” (letter C in Fig. 2) and “To stay healthy, . . . FDA tips: Do not eat any raw cookie dough, cake mix, batter or any other raw dough or batter product that's supposed to be cooked or baked” (letter E in Fig. 2). This suggests that strategically designed consumer educational messages can surge consumers' online activities, which may lead to an increased awareness of flour food safety among consumers. A previous survey study reported that different flour warning messages could lead to different degrees of change in behavior intention among consumers ( 20 ). Although the analysis in the current study cannot help gain understanding of consumers' knowledge and behavior intention change, the increasing number of mentions on the social media implies more consumers are interested in the warning messages ( 28 ).

Future studies can conduct further analysis on consumer reaction to those warning messages from the FDA, which can help develop more effective social media engagement tools for consumer food safety education. In addition, there is also variation in the number of mentions regarding information about flour-borne food safety risks. Unlike the peaks representing recalls, mentions rise around the holiday season in November and December 2017. As expected, seasonal increases in flour-related illness comments increase during peak periods of use during the holiday baking season. From the limited data analyzed, this trend appears more predictable than the rather heterogeneous increases in media volume accompanying a recall or illness announcement.

Sentiment of flour searches

The more the recalls made by the FDA, the more mentions appear in social media spaces. Subsequently, the more the mentions of flour recalls are posted on social media, the more negative the net sentiment will be. Table 5 renders this aspect more evident with a Pearson correlation coefficient. Monthly and weekly mentions and net sentiments are negatively correlated, and both are statically significant. This suggests that people in social and online media spaces track and reflect flour-related illnesses in a timely manner. They are also negatively, albeit weakly, correlated for the general flour search. However, net sentiment is still positive for the general flour search.

TABLE 5.

Results of the hypothesis test for the Pearson correlation with volume of mentions and net sentiment

| Pearson correlation coefficienta | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| General flour search | ||

| Monthly mentions and sentiments | −0.1209 | 0.4514 |

| Weekly mentions and sentiments | −0.1452* | 0.0524 |

| Flour-related illness search | ||

| Monthly mentions and sentiments | −0.4751** | 0.0002 |

| Weekly mentions and sentiments | −0.3075** | 2.8248e−05 |

P < 0.1; ** P < 0.01.

Two potential factors contribute to consumers' misperceptions of flour. First, food safety risk of flour was not widely recognized by consumers. Recent consumer survey results showed that 85% flour consumers were not aware of any recalls or outbreaks associated with wheat flour. Consumer awareness of food safety risks is associated with high-profile foodborne incidents. For example, many consumers started to be cautious of ground beef after the widely reported 1993 Jack in the Box outbreak; this outbreak was used as a case study in many food safety books and publications ( 5 , 47 , 48 ). Second, consumers gauge risks and benefits when making decisions regarding food. When perceived benefits outweigh risks, consumers tend to overlook food safety as a potential concern. For example, a study of raw milk consumers showed that they focus on health and taste benefits rather than potential food safety risks ( 6 , 39 ).

Implications for flour safety communication

This current study demonstrated that online media responses to announcements of flour recalls are heterogeneous in scale. Previously, 84% of consumers had self-reported they paid close attention to food recalls ( 24 ). However, many factors could contribute to the phenomenon in which consumers want to pay attention to food recalls but do not actually do this when observed. First, there are too many food recalls for consumers to follow. In 2019 alone, there were over 300 food recalls issued by the FDA and U.S. Department of Agriculture ( 21 ). Many were rolling or expanding recalls, which may not be relevant to consumers. Second, consumers may be misled by the language used in recall announcements. Food recalls are voluntary or initiated by the FDA. Those recalls are classified as class I, II, or III, depending on the risk to the public ( 8 , 35 ). Therefore, some words used in recall messages (on the basis of the classification) may be misleading; for example, a “voluntary recall” may be perceived as less important by consumers. Additionally, consumers may perceive class I recalls as less severe than class III recalls.

The majority of media about flour is about its use, and relatively small shares of media attention are devoted to safety. Thus, additional flour safety education programs may be desired to support consumers in informed decision making, especially as interest in baking and home use of flour as a raw ingredient increases. The education can be conducted focusing on potential risks of flour, how to access proper outbreak and recall announcements, or how to interpret food risk information. The main findings that people in social media space react to general flour searches, information or warnings of potential flour-borne illnesses, and flour recalls by the FDA, albeit weakly, may also suggest that social media can play an important role in keeping people informed about flour and related illnesses.

Overall remark and limitations

As more people now reside in online and social media spaces, data collected from online and social media spaces can be useful. Compared with traditional methods of collecting data, such as a survey or interview, online and social media data can provide more real-time and unprompted information about people's behavior and opinion. When it comes to provision of real-time information, this is one important aspect of exploiting online and social media data for emergency management by the government. In particular, food safety is one of emergency management, and this study shows real-time reactions of people in social media spaces to flour and flour-related illness outbreaks and recalls. As found in this study, people are immediately responsive to flour-related recalls, albeit small in magnitude. This may be just a revisiting of what has been found from previous studies about perception of flour-related illnesses, but the imminent responses of more people in social media space may suggest that social media can be an effective media for providing education and information on flour-related illnesses and food safety messages.

Although this study was carefully planned and executed, there were some limitations. Mentions and sentiments may not be an accurate representation of all consumers in the United States due to the nature of the online data collection process. Some consumers may not have had access to the Internet or social media. Future research could delve into possible factors, such as misleading articles and article titles, frequency of discussion of flour-related illnesses in popular cooking outlets, and the level of emphasis on the severity of consuming raw cookie dough in educational resources. By identifying possible sources of misleading information, the underlying framework of consumers' perception of flour can be better understood. As a result, government agencies and health care facilities may be better able to dismantle inaccurate perceptions of flour-related illnesses and provide educational intervention to encourage safe flour handling behaviors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nicole Olynk Widmar acknowledges financial support from the OEVPRP (Office of the Executive Vice President for Research and Partnerships) Non-Laboratory Equipment Program. This material is partially supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Hatch projects 1016049 and 2020-68012-31822.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allagui I., Breslow H. Social media for public relations: lessons from four effective cases. Public Relat. Rev. 2015;42:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo T., van der Meer T.G.L.A. News values on social media: exploring what drives peaks in user activity about organizations on Twitter. Journalism. 2018;21:633–651. doi: 10.1177/1464884918809299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnade C., Kuchler F., Calvin L. Consumers' response when regulators are uncertain about the source of foodborne illness. J. Consum. Policy. 2013;36:17–36. doi: 10.1007/s10603-012-9217-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beecher C. Consumers need wake-up call about potential dangers of flour. Food Safety News. 2019 https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2019/08/consumers-need-wake-up-call-about-potential-dangers-of-flour/ Available at: . Accessed 20 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedict J. February Books; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigouette J.P., Bethel J.W., Bovbjerg M.L., Waite-Cusic J.G., Häse C.C., Poulsen K.P. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding raw milk consumption in the Pacific Northwest. Food Prot. Trends. 2018;38:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd-Bredbenner C., Abbot J.M., Wheatley V., Schaffner D., Bruhn C., Blalock L. Risky eating behaviors of young adults—implications for food safety education. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008;108:549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jada. . 2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capaldo S. Evaluation of food recalls and withdrawals trends between 2014 and 2018 and risk management tools to reduce the financial impact of a recall. 2020 https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/99721 Virginia Tech. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Foodborne illnesses and germs. 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html Available at: . Accessed 23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food safety education month, social media messages. 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/fs-education-month-social.html Available at: . Accessed 23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reports of active Salmonella outbreak investigations. 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks-active.html Available at: . Accessed 23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reports of E. coli outbreak investigations from 2020. 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2020-outbreaks.html Available at: . Accessed 23 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole-Lewis H., Pugatch J., Sanders A., Varghese A., Posada S., Yun C., Schwarz M., Auguston E. Social listening: content analysis of e-cigarette discussions on Twitter. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015 doi: 10.2196/jmir.4969. https://www.jmir.org/2015/10/e243/ Available at: 17:e243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colicev A., O'Connor P., Vinzi V.E. Is investing in social media really worth it? How brand actions and user actions influence brand value. Serv. Sci. 2016;8:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dos Santos M.J.P.L. Nowcasting and forecasting aquaponics by Google Trends in European countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2018;134:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore. . 2018.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducange P., Fazzolari M., Petrocchi M., Vecchio M. An effective Decision Support System for social media listening based on cross-source sentiment analysis models. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intel. 2019;78:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Y., Archila J. Consumer knowledge and behaviors regarding food safety risks associated with wheat flour. J. Food Prot. 2021;84:628–638. doi: 10.4315/jfp-19-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Food Safety Magazine. A look back at 2019 food recalls. 2021 https://www.food-safety.com/articles/6487-a-look-back-at-2019-food-recalls#:∼:text=Listeria%2C%20Salmonella%2C%20and%20E.&text=Approximately%2060%20food%20products%20were Available at: , pet%20food%20and%20baby%20spinach. Accessed 31 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallagher A., Chen T. Estimating age, gender and identity using first name priors. Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2008 , Anchorage, Alaska, 24 to 26 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasco L., Clavel C., Asensio C., de Arcas G. Beyond sound level monitoring: Exploitation of social media to gather citizens subjective response to noise. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;658:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glowacki E.M., Glowacki J.B., Chung A.D., Wilcox G.B. Reactions to foodborne Escherichia coli outbreaks: a text-mining analysis of the public's response. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2019;47:1280–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallman W.K., Cuite C.L., Hooker N.H. Rutgers University; New Brunswick, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris L.J., Yada S. Flour and cereal grain products: foodborne illness outbreaks and product recalls: tables and references. 2020 https://ucfoodsafety.ucdavis.edu/low-moisture-foods/lowmoisture-foods-other-products Available at: . Accessed 13 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer-Shall Z. Forrester Research; Cambridge, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Influencer Marketing Hub. Top 20 social media listening tools for 2020. 2020 https://influencermarketinghub.com/top-social-media-listening-tools/ Availabele at: . Accessed 20 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob C., Mathiasen L., Powell D. Designing effective messages for microbial food safety hazards. Food Control. 2010;21:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung J., Bir C., Widmar N.O., Sayal P. Initial reports of foodborne illness drive more public attention than food recall announcements. J. Food Prot. 2021;84:1150–1159. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim A.J., Ko E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customers equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012;65:1480–1486. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchler F. U.S. Department of Agriculture; Washingon, DC: 2015. How much does it matter how sick you get? (Consumers' responses to foodborne disease outbreaks of different severities). ERR-193. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuttschreuter M., Rutsaert P., Hilverda F., Regan Á., Barnett J., Verbeke W. Seeking information about food-related risks: the contribution of social mint model of sentiment and venue formedia. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014;37:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai J., Widmar N.O. Revisiting the digital divide in the COVID-19 era. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 2020;43:458–464. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.J., Lappeman, R., Clark J., Evans L., Sierra-Rubia and P.Gordon Studying social media sentiment using human validated analysis . MethodsX7: 100867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lee L.E., Metz D., Giovanni M., Bruhn C.M. Consumer knowledge and handling of tree nuts: food safety implications. Food Prot. Trends. 2011;31:18–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.LexisNexis. See a historical perspective with news archives. 2018 https://www.lexisnexis.com/en-us/products/nexis/news-archives.page Available at: . Accessed 24 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lister S.A., Becker G.S. Congressional Research Service; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lusk J.L., Briggeman B.C. Food values. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009;91:184–196. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma J., Almanza B., Ghiselli R., Vorvoreanu M., Sydnor S. Food safety information on the Internet: consumer media preferences. Food Prot. Trends. 2017;37:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahoney J.A., Widmar N.J.O., Bir C.L. #GoingtotheFair: a social media listening analysis of agricultural fairs. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020;4:1–13. doi: 10.1093/tas/txaa139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markham L., Auld G., Bunning M., Thilmany D. Attitudes and beliefs of raw milk consumers in northern Colorado. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2014;9:546–564. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2014.929542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLeod S.A. What a p-value tells you about statistical significance. 2019 https://www.simplypsychology.org/p-value.html Available at: . Accessed 28 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myoda S.P., Gilbreth S., Akins-Lewenthal D., Davidson S.K., Samadpour M. Occurrence and levels of Salmonella, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, and Listeria in raw wheat. J. Food Prot. 2019;82:1022–1027. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NetBase. Next generation artificial intelligence. 2019 https://netbasequid.com/applications/next-generation-artificial-intelligence/#:~:text=NetBase%2C%20the%20industry%20leader%20in%20next%20generation%20artificial%20Intelligence%2C%20is,that%20drive%20ideation%20and%20innovation Available at: . Accessed 17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pardoe I. Penn State University; University Park, PA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rude E. The coronavirus baking boom has made it hard to find flour. Here's how Americans coped with “wheatless Wednesdays” in WWI. 2020 https://time.com/5836012/flour-shortage-history/ Available at: . Accessed 17 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rutsaert P., Regan Á., Pieniak Z., McConnon Á., Moss A., Wall P., Verbeke W. The use of social media in food risk and benefit communication. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013;30:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schweidel D.A., Moe W.W. Listening in on social media: a joint model of sentiment and venue format choice. J. Mark. Res. 2014;54:387–402. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seo S., Jang S., Almanza B., Miao L., Behnke C. The negative spillover effect of food crises on restaurant firms: did Jack in the Box really recover from an E. coli scare? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014;39:107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon M. Jack in the Box surprise: how E. coli became a household word. 2011 https://grist.org/scary-food/2011-05-09-jack-in-the-box-surprise-how-e-coli-became-a-household-word/ Available at: . Accessed 11 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thelwall M., Buckley K., Paltoglou G. Sentiment in Twitter events. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011;62:406–418. doi: 10.1002/asi.21462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas M., Feng Y. Risk of foodborne illness from pet food: assessing pet owners' knowledge, behavior, and risk perception. J. Food Prot. 2020;83:1998–2007. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas M., Feng Y. Food handling practices in the era of COVID-19: a mixed-method longitudinal needs assessment of consumers in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2021;84:1176–1187. doi: 10.4315/JFP-21-006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas M., Haynes P., Archila J., Nguyen M., Xu W., Feng Y. Exploring food safety messages in an era of COVID-19: analysis of YouTube video content. J. Food Prot. 2021;84:1000–1008. doi: 10.4315/JFP-20-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tirunillai S., Tellis G.J. Does chatter really matter? Dynamics of user-generated content and stock performance. Mark. Sci. 2012;31:198–215. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tonsor G.T., Olynk N.J. Impacts of animal well-being and welfare media on meat demand. J. Agric. Econ. 2011;62:59–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-9552.2010.00266.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.N. A., Vidya, M. I., Fanany and I.Budi Twitter sentiment to analyze net brand reputation of mobile phone providers . Procedia Comput. Sci. 72: 519– 526.

- 56.Widmar N.O. “Big data” provides insights to public perceptions of USDA. 2020 http://www.choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/submitted-articles/big-data-provides-insights-to-public-perceptions-of-usda Available at: . Accessed 1 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Widmar N.O., Bir C., Clifford M., Slipchenko N. Social media sentiment as an additional performance measure? Examples from iconic theme park destinations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102157. 56:102157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Widmar N.O., Bir C., Lai J., Wolf C. Public perceptions of veterinarians from social and online media listening. Vet. Sci. 2020;7:75–86. doi: 10.3390/vetsci7020075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Widmar N.O., Bir C., Wolf C., Lai J., Liu Y. #Eggs: social and online media derived perceptions of egg laying hen housing. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:5697–5706. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yadav M., Rahman Z. Measuring consumer perception of social media marketing activities in e-commerce industry: scale development & validation. Telemat. Inform. 2017;34:1294–1307. [Google Scholar]