Abstract

Benzalkonium salts are widely used in the composition of antimicrobial preparations in industry and everyday life and as algaecides to treat pool water. The disinfection of tap or waste water with active chlorine in the presence of natural or anthropogenic bromide anions or using bromine as a pool water disinfectant creates conditions for the interaction of benzalkonium cations with active bromine to form disinfection by-products. This study presents the results of a model benzalkonium bromination with the identification of the resulting products by high-performance liquid and gas chromatography combined with high-resolution mass spectrometry. The primary transformation products are monobromo derivatives formed by the radical substitution of hydrogen atoms of the alkyl chain with bromine. Their further transformations yield dibromo-, hydroxy-, and hydroxybromo derivatives. The final products of the deep degradation of benzalkonium are bromoform, bromoacetonitrile, and several brominated hydrocarbons.

Keywords: benzalkonium chloride, algaecide, high-resolution mass spectrometry, bromination, water disinfection, disinfection by-products

INTRODUCTION

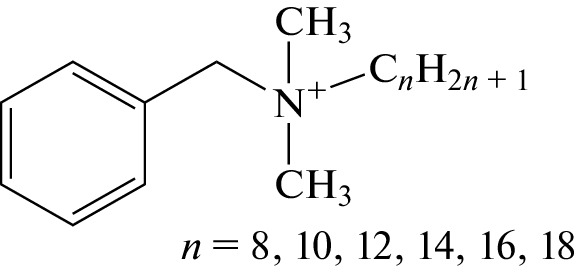

Benzalkonium (alkyldimethylbenzylammonium, BA) cations are quaternary ammonium compounds (Fig. 1) differing in the length of the saturated alkyl chain; in commercially available preparations, the chain may consist of 8 to 18 carbon atoms. Because of their surfactant properties and the ability of binding to certain proteins, they possess pronounced antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal effects. They are widely used as antimicrobial agents in the form of salts (usually benzalkonium chloride) in the production of personal care products, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals, for disinfection in everyday life and the food industry [1, 2]. The pandemic outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronavirus increased the consumption of benzalkonium chloride significantly [3], which naturally led to an increase in the ingress of this compound into wastewaters. Moreover, benzalkonium is considered a promising disinfectant for the destruction of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater [4]. Even more ambitious is the use of benzalkonium salts as an algaecide for pool water, which prevents the development of microalgae [5]. The dosages used in this case can reach 1 mg L–1 [6], which makes benzalkonium one of the key contaminants in pool water, making a significant contribution to the formation of hazardous disinfection by-products.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the benzalkonium cation.

Despite the apparent inertness of the structure, benzalkonium undergoes various transformations during the disinfection of tap and waste water [7–9]; under the action of active chlorine, it can form a wide range of halogenated and oxygen-containing derivatives even in the absence of light. One or several chlorine atoms are introduced only in the alkyl chain by the mechanism of radical substitution, while the benzyl group and methyl radicals at the nitrogen atom remain intact. The resulting chlorinated derivatives further interact with water and oxidants to form hydroxyl and keto derivatives. In pool water, benzalkonium transformation products were found at a level of μg L–1 with the predominance of monochlorinated derivatives [6].

Active bromine is an alternative disinfectant for pool water, especially in hot climates and in the spa industry. It is widely used because of the less pronounced smell of treated water, the absence of irritating effects on the skin, or the whitening effect on synthetic fabrics [10, 11]. In the processes of water disinfection with chlorine, active bromine can also play an important role in the formation of by-products, because it occurs during the oxidation of bromide ions present in water with chlorine and has higher reactivity in interacting with organic substances compared to the active chlorine [12, 13]. For example, we previously detected bromo derivatives of fatty acid amides [14], bromophenols and bromobenzoic acids [15], and other brominated compounds of medium volatility [16, 17] in tap water disinfected with hypochlorite, in addition to chlorine-containing products. Active bromine is also often present as an impurity in industrial chlorinating agents [16, 17].

In this regard, the purpose of this work was to study the interaction of benzalkonium cations with active bromine in the processes of water disinfection and to compare the reactivity and transformation pathways of this quaternary ammonium compound under the action of active chlorine and bromine. We chose high-performance liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry (HPLC–HRMS) with electrospray ionization (ESI) as the main analytical method, which ensures the highly sensitive detection of thermolabile analytes and was successfully used to identify the transformation products of such nitrogen-containing compounds as fatty acid amides, doxazosin, and umifenovir [14, 18, 19].

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and materials. A benzalkonium chloride preparation (>95%, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), which was a mixture of two homologues with dodecyl (BA-12, 73.5%) and tetradecyl (BA-14, 24.6%) substituents, was used as a model sample for water bromination.

Potassium dichromate, hydrochloric acid (38%), sulfuric acid, and sodium hydroxide were used to obtain bromine and prepare buffer solutions with a given pH value (all of chem. pure grade, Neva-Reaktiv, Russia). We also used orthophosphoric acid (chem. pure grade, KomponentReaktiv, Russia), sodium bromide (ACS Reagent, >99.0%), and one- and two-substituted sodium phosphate (ReagentPlus, >99.0%) produced by Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). To stop the bromination reaction, we used sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (volumetric standard, Uralkhiminvest, Russia).

The mobile phase in the HPLC analysis was prepared from acetonitrile (supergradient grade, PanReac, Spain), formic acid (ACS Reagent, puriss, p.a., Germany), and high-purity water prepared using a Milli-Q system (Millipore, France). For extracting products from the reaction mixture, we used dichloromethane (ACS Reagent, stabilized with amylene) and anhydrous sodium sulfate (ACS Reagent) purchased from PanReac (Spain).

Elemental bromine was obtained by reacting sodium bromide with potassium bichromate in the presence of conc. sulfuric acid, followed by distillation and washing with water [20]. A saturated solution of bromine in water (bromine water) was obtained by adding an excess of elemental bromine to 250 mL of water, after which the solution was transferred to a sealed glass container and stored at a temperature of 4°C. According to the data of titrimetric analysis (iodometry), the concentration of active bromine in the solution was 17.9 g L–1.

Bromination. The stock aqueous solution of a mixture of BA-12 and BA-14 with a total concentration of 1 g L–1 was prepared by the weight method. Working solutions with a volume of 20 mL with a total concentration of homologues of 10 mg L–1 and pH 8.2, 7.0, 6.2, and 5.4 were prepared in 60-mL glass vials with PTFE septa by diluting the stock solution with a 100 mM phosphate buffer solution of a corresponding pH value. Bromine water was added to each working solution until active bromine concentration reached 100 mg L–1. The reaction was carried out for 5 days at ambient temperature (20 ± 2°C) upon continuous stirring using an orbital shaker and room lighting. Solutions without the addition of bromine, prepared in the same manner, were kept under identical conditions and used as control samples. Portions of reaction mixtures and reference samples of a volume of 200 μL were periodically taken, and the reaction was stopped by adding a sodium thiosulfate solution. The mixture was filtered and analyzed by HPLC–HRMS.

For GC–MS studies, the reaction mixtures and reference samples (10 mL) were subjected to extraction with dichloromethane. To do this, after stopping the reaction with sodium thiosulfate, a 3-mL portion of the extractant was added, the mixture was thoroughly stirred, and the organic phase was taken after the separation of the layers. The procedure was repeated three times. The obtained extracts were combined, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, evaporated under high-purity (99.99%) nitrogen to 300 μL, and transferred into a vial with a 250-μL conical insert.

Analysis by chromatography–mass spectrometry. High-resolution liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry studies were carried out using a TripleTOF 5600+ quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) mass spectrometer (ABSciex, Canada) equipped with a Duospray ion source, in combination with an LC-30 Nexera HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan), consisting of a DGU-5A vacuum degasser, two LC-30AD pumps, a SIL-30AG autosampler, and an STO-20A column thermostat.

Chromatographic separation was carried out at 40°C in a Nucleodur PFP column (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) 150 × 3 mm, particle size 1.8 μm, with a pentafluorophenyl propyl stationary phase. A mixture of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), containing 0.1% of formic acid, was used as a mobile phase. The following gradient program was used: 0–1 min, 10% of B; 1—25 min, linear increase in the proportion of B up to 100%; 25–40 min, 100% of B. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 0.25 mL min–1; the injected sample volume was 2 μL.

Screening of disinfection by-products was carried out using an information-dependent data acquisition (IDA) with electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode. The following parameters of the ion source were used: nebulizing (GS1) and drying (GS2) gas pressure 40 psi, curtain gas pressure (CUR) 30 psi, capillary voltage (ISVF) 5500 V, source temperature (TEM) 300°C, declustering potential (DP) 80 V. Mass spectra were continuously recorded in the range m/z 100–1000 with a signal accumulation time of 150 ms. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) tandem mass spectra were recorded in the range m/z 20–1000 for those precursor ions the signal intensity of which in the spectrum exceeded 100 cps. We used collision energy (CE) of 40 eV with a spread (CES) of 20 eV; the accumulation time of the CID spectra was 50 ms. Nitrogen was used as a collision gas.

The mass scale was calibrated before each HPLC–MS analysis in an automatic mode using a sodium formate solution as a reference according to the signals of the formed ion clusters in the range m/z 91–1000.

The obtained results were processed using the PeakView, MasterView, and Formula Finder software (ABSciex, Canada). The elemental compositions of the ions of the compounds to be detected were determined from their accurate masses, isotope distributions, and CID spectra. The following constrains were applied: the maximum number of atoms C 50, H 100, O 20, N 1, and Br 10; error in determining m/z <5 ppm (MS) and <10 ppm (MS/MS); signal-to-noise ratio >10.

The GC–MS identification of volatile and semivolatile products of the transformation of benzalkonium chloride was carried out using an Orbitrap Exactive GC (Thermo Scientific, United States) system, consisting of a Trace 1310 gas chromatograph with a TriPlus RSH autosampler and a high-resolution mass analyzer based on an orbital ion trap. Analytes were separated in a TG-5SILMS capillary column (Thermo Scientific, United States), 30 m in length, 0.25 mm in inner diameter, with a stationary phase film thickness of 0.25 μm. The flow rate of the mobile phase (helium, 99.9999%) was 1.2 mL min–1. The following column thermostat program was used: initial temperature 50°C for 3 min; rise to 300°C at a rate of 7°C min–1; 10 min held at 300°C. A 1-μL sample of the extract was injected with a 5 : 1 flow splitting. The temperatures of the injector and transfer line were 280 and 300°C, respectively. Mass spectrometric detection was carried out in the range m/z 35–550 at a mass analyzer resolving power of 60 000 (for m/z 200). The target filling value of the C-Trap quadrupole ion trap (AGC Target) was 5 × 105. The following parameters of the ion source were used: electron ionization (EI) at an energy of 70 eV; temperature 200°C. The GC–MS data were processed using Xcalibur and Trace Finder software (Thermo Scientific, United States).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Primary bromination products and reaction mechanism. Taking into account that the initial benzalkonium is a quaternary ammonium cation, an analysis of reaction mixtures by HPLC–MS/HRMS to search for primary transformation products was carried out in the positive ion mode. Structures capable of deprotonation and requiring the use of ESI in the negative ion mode (for example, carboxylic acids) can form only by deep degradation of benzalkonium, when the use of GC–MS methods becomes more effective. The results suggested the detection and presumable identification of four transformation products of BA-12 and BA-14, formed without the destruction of the carbon backbone of the initial compounds (Fig. 2). These include products of the substitution of one or two hydrogen atoms with bromine (mono and dibromo derivatives), hydroxylated benzalkonium cations containing one OH group, and mixed hydroxybromo derivatives with one hydroxyl group and one bromine atom in their structure. The specific shape of the chromatographic peaks indicates the presence of many poorly separated isomeric compounds with close polarity. This means that the introduction of substituents occurs at different positions of the aliphatic chain in the benzalkonium structure and excludes the presence of a single reaction center (for example, the benzyl carbon atom).

Fig. 2.

Extracted ion chromatograms of (a) monobromo, (b) dibromo, (c) hydroxyl, and (d) hydroxybromo derivatives of BA-12 and BA-14 in the reaction mixture (reaction time 48 h, pH 5.4).

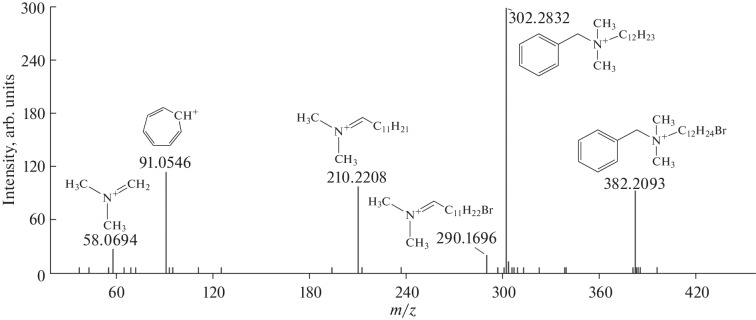

The CID mass spectra give additional structural information that reveals the priority groups for the attack of active bromine in the benzalkonium cation. The spectrum of the monobrominated derivative BA-12 [C21H37NВr]+ (Fig. 3) shows signals of product ions obtained with the elimination of HBr, cleavage of the bond between the benzyl carbon atom and the nitrogen atom, and the N,N-dimethylmethaniminium cation. Attention is drawn to the presence of bromine only in the composition of fragments with a dodecyl substituent; cleavage of the carbon–nitrogen bond with the charge retained on the benzyl carbon atom leads to the formation of only the tropylium cation [C7H7]+ rather than benzyl bromide or bromotoluene with substitution in the aromatic ring. This confirms that benzalkonium is brominated exclusively by the alkyl chain by the mechanism of radical substitution with the initiation of the process under the action of light. Structures that are more reactive at first sight—the aromatic nucleus and the benzyl carbon atom—are inactivated, apparently, because of the effect of quaternary nitrogen. The methyl groups at the nitrogen atom are also inactive. This is evidenced by the already mentioned peak of N,N-dimethylmethaniminium (m/z 58.0694) in the CID spectrum.

Fig. 3.

CID mass spectrum of the monobromo derivative of BA-12 (m/z 382.2093) and assignment of product ion peaks.

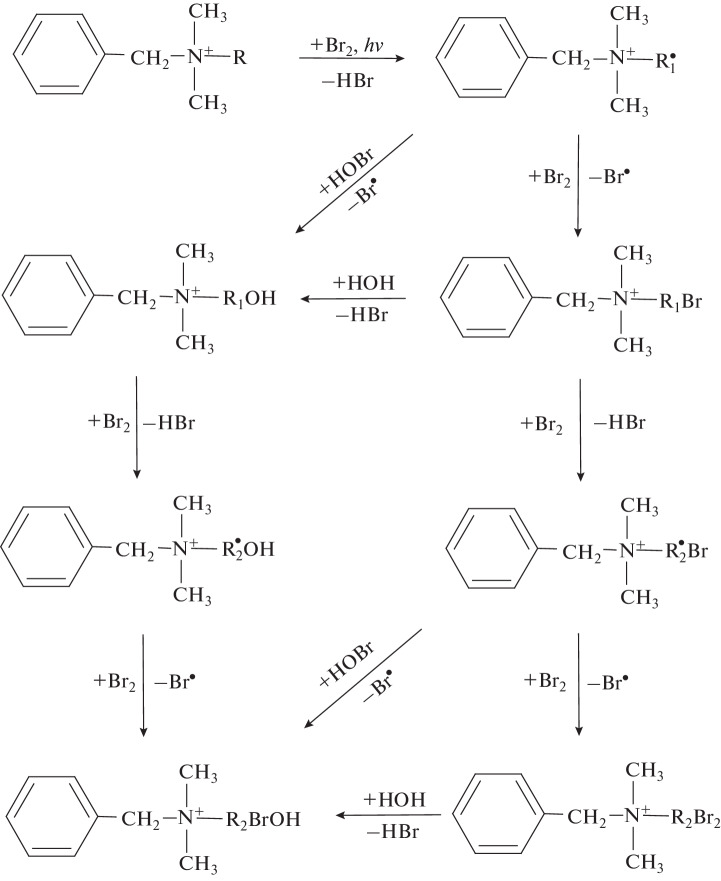

A similar pattern is also characteristic of the other BA-12 and BA-14 derivatives found, proposing a mechanism for the transformation of the benzalkonium cation in aqueous solutions under the action of active bromine (Fig. 4). The primary stage is the formation of a monosubstituted bromo derivative, followed by the nucleophilic substitution of the bromine atom by a hydroxyl group and the introduction of an additional bromine atom into the monobromo derivative or hydroxylated benzalkonium cation. At the selected pH values of the solution, a significant part of the active bromine can occur in the form of hypobromous acid; therefore, an alternative way to form the hydroxylated derivative of benzalkonium is the radical cleavage of HOBr and the addition of the resulting hydroxyl radical to the radical center of the alkyl chain. The formation of the latter occurs because of homolytic cleavage of the C–H bond under the action of molecular bromine. As the mechanism of the radical substitution of hydrogen by bromine in a long alkyl chain assumes almost equally probable participation of any of its units, the reaction product is a set of isomers with close dipole moments, which are difficult-to-separate under reversed-phase HPLC conditions.

Fig. 4.

Transformation mechanism of the benzalkonium cation under conditions of aqueous bromination (R = CnH2n + 1; R1 = CnH2n; R2 = CnH2n – 1).

The described reaction mechanism and the transformation pattern are similar to those observed in benzalkonium chlorination [6]. Nevertheless, there are significant differences in the action of the two halogens, associated with the course of the oxidation of the primary products of benzalkonium transformation. Under chlorination conditions, the most important products are oxo derivatives with a keto group in the alkyl chain, which account for up to 30% of the initial benzalkonium, while during bromination under similar conditions, these compounds are not detected in the reaction mixture. This behavior is explained by the fact that bromine is a less powerful oxidant than chlorine, and the formation of ketones is associated precisely with the oxidation of intermediate alcohols as precursors.

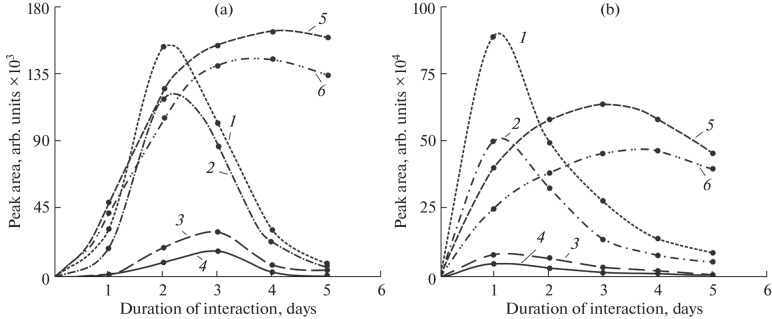

Dynamics of the transformation of benzalkonium cations under conditions of aqueous bromination. As in the case of chlorination [6], the change in the concentration of the initial BA-12 and BA-14 best corresponds to the kinetics of first-order reactions. The dynamics of changes in the concentrations of the resulting products is of greatest interest (Fig. 5). The concentration of mono- and dibromo derivatives passes through a pronounced maximum at an interaction time of 1–2 days, which indicates that they act as primary intermediate products of benzalkonium transformation. At the maximum, the concentration of these products reaches ~5% of the initial benzalkonium concentration. According to the mechanism described above (Fig. 4), they are converted into hydroxy derivatives at the next stage, the concentration of which reaches a maximum (3–4.5% of the initial benzalkonium) 3–4 days after the onset of the reaction. This situation is also characteristic of dibromo derivatives, which form in much smaller amounts (up to 0.5% of the initial benzalkonium). The rate of benzalkonium transformation reactions under the action of active bromine was significantly lower compared to the rate of chlorination. Even in the absence of light, chlorination under conditions similar to those in the present study ensured for a comparable time the formation of monochloro and dichloro derivatives in amounts of the order 10 and 5% of the initial benzalkonium, respectively [6], and products containing up to four chlorine atoms were detected in the reaction mixtures. This is in full agreement with the radical mechanism of the process, in which chlorine is more reactive than bromine.

Fig. 5.

Dynamics of changes in the concentrations of the transformation products of benzalkonium cation under the action of active bromine at pH (a) 8.2 and (b) 6.2. Curve numbers correspond to (1 and 2) monobromo derivatives, (3 and 4) dibromo derivatives, and (5 and 6) hydroxy derivatives of BA-12 and BA-14, respectively.

A comparison of the results obtained at different pH values, as expected, shows a significant acceleration of the reaction with an increase in the acidity of the medium: in going from pH 8.2 to 6.2, the time to reach the maximum concentrations of primary products is decreased by 1.5–2 times, while the concentrations themselves increase up to five times. This can be explained by the formation of more reactive species [21]: molecular bromine and hypobromite anion. A decrease in the total concentration of primary products of benzalkonium transformation 1–2 days after the start of the reaction in the absence of new compounds identified by HPLC–HRMS suggests the accumulation of products of deep benzalkonium degradation in the reaction mixture, which do not contain a charge in their structure or are difficult to ionize under electrospray ionization conditions.

Products of the deep destruction of benzalkonium. GC–HRMS was used to characterize the final products of benzalkonium bromination, formed as a result of the deep degradation of the parent compound. The test samples were dichloromethane extracts of samples of reaction mixtures collected 5 days after initiation of the reaction by the addition of active bromine, when the concentration of primary products of benzalkonium transformation sharply decreases (Fig. 5). The results showed the presence of nine volatile and semivolatile organobromine compounds in solutions (Table 1). Among them, bromoform dominates, accounting for more than 80% of the total area of chromatographic peaks of the compounds of this group. Bromoacetonitrile, dibromobutane, tetrabromomethane, and some unidentified heavier brominated compounds containing more than five carbon atoms and not forming molecular ions in the EI mass spectra are also found in significant amounts. A [C5H10Br]+ ion, apparently characterized by increased stability, dominates in the mass spectra of these compounds. Determining their structure requires additional studies using chemical ionization and tandem mass spectrometry; this issue was beyond the scope of this study. Taking into account the elemental composition of the dominant ion, we assume these are products of the destruction of the alkyl chain, which may include both brominated alkanes and some oxygen-containing bromo derivatives, including alcohols, aldehydes, and acids.

Table 1.

Results of the GC–HRMS analysis of benzalkonium deep degradation products under the action of active bromine at various pH

| No. | tR, min | m/z | Elemental composition of the characteristic ion | Error, ppm | Compound | Peak area, arb. units, at pH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.4 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 8.2 | ||||||

| 1 | 5.09 | 249.7621 | CHBr3([M]•+) | –0.78 | Tribromomethane | 490 | 450 | 370 | 260 |

| 2 | 5.85 | 172.8418 | C2HNBr([M-H]•+) | –0.26 | Bromoacetonitrile | 3.4 | 2.9 | 0.82 | 0.38 |

| 3 | 7.34 | 212.8909 | C4H7Br2([M-H]•+) | –0.47 | Dibromobutane | 5.4 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 9.27 | 248.7543 | CBr3([M-Br]•+) | –0.59 | Tetrabromomethane | 5.0 | 1.5 | 0.50 | 0.41 |

| 5 | 17.71 | 148.9962 | [C5H10Br]+ | 0.77 | – | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.038 | 0.025 |

| 6 | 19.62 | 148.9959 | [C5H10Br] + | –0.71 | – | 16 | 13 | 7.2 | 1.3 |

| 7 | 21.43 | 148.9961 | [C5H10Br]+ | 0.16 | – | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.041 | 0.025 |

| 8 | 23.13 | 148.9960 | [C5H10Br]+ | –0.32 | – | 3.3 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| 9 | 24.75 | 148.9960 | [C5H10Br]+ | –0.15 | – | 0.067 | 0.046 | 0.020 | 0.011 |

The trend towards a decrease in the yield of products of deep benzalkonium degradation with an increase in the pH of the reaction mixtures is rather pronounced (Table 1). This effect is explained by a shift in the equilibrium between hypobromite ions in solution and free bromine (or hypobromous acid, pKa = 8.65). The last substances is more active brominating agents and stronger oxidants; the standard redox potentials (E0) of the systems Br2/2Br–, 2HOBr + 2H+/Br2 + 2H2O and HOBr + H+/Br– + H2O are 1.09, 1.60, and 1.34 V, respectively, while for the pair BrO– + H2O/Br– + 2OH–, E0 = 0.76 V [22]. As the oxidant properties of the active forms of halogens play the key role in the destruction of organic compounds during disinfection, the observed difference in the chemical composition of the products of benzalkonium bromination and chlorination becomes understandable [6]. As noted above, the presence of active chlorine in the solution creates a more oxidizing environment compared to bromine, and, therefore, chlorination under similar conditions yields a significantly larger number (about 30) of benzalkonium deep degradation products.

CONCLUSIONS

Benzalkonium cations can interact with active bromine in aqueous solutions by the mechanism of the photoinitiated radical substitution of a halogen in the alkyl chain with the formation of monobromo and dibromo derivatives; the aromatic ring, methyl substituents at the nitrogen atom, and the benzyl carbon atom remain inactive. The nucleophilic substitution of bromine with a hydroxyl group leads to the formation of hydroxy derivatives at the next stage. Equal probabilities of interaction with different parts of the alkyl chain result in the formation of a wide range of isomeric compounds with similar properties in the ongoing reactions. A decrease in pH accelerates the bromination reaction by shifting the equilibrium of the forms of active bromine in solution towards the formation of free bromine and hypobromous acid, which are more reactive. Prolonged exposure to active bromine leads to the deep destruction of benzalkonium with the formation of predominantly bromoform, as well as bromoacetonitrile and several bromoalkanes. In contrast to chlorination, the transformation of benzalkonium under the action of active bromine proceeds under milder conditions with the less pronounced oxidation and deep destruction of the initial compounds. A possibility of the formation of benzalkonium bromination products during water disinfection must be taken into account in developing and optimizing technologies for water and wastewater treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work used the equipment of the Core Facility Center “Arktika” of the Northern (Arctic) Federal University.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation, project no. 21-13-00377.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Translated by O. Zhukova

Contributor Information

N. V. Ul’yanovskii, Email: n.ulyanovsky@narfu.ru

D. S. Kosyakov, Email: d.kosyakov@narfu.ru

REFERENCES

- 1.Ash, M. and Ash, I., Handbook of Preservatives, Endicott: Synapse Inf. Resources, 2009.

- 2.Halvax J.J., Wiese G., Arp J.A. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1990;8:243. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(90)80033-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah K., Chhabra S., Chauhan N. Biomed. Biotechnol. Res. J. 2021;5:121. doi: 10.4103/bbrj.bbrj_16_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakur A.K., Sathyamurthy R., Velraj R. J. Environ. Manage. 2021;290:112668. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford M.J., Tetler L.W., White J. J. Chromatogr. A. 2002;952:165. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(02)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ul’yanovskii, N.V., Kosyakov, D.S., Varsegov, I.S., et al., Chemosphere, 2020, vol. 239, no. 124801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chang H., Chen C., Wang G. Water Res. 2011;45:3753. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang H.H., Wang G.S. Water Sci. Technol. 2011;64:2395. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang N., Wang T., Wang W.L. Water Res. 2017;114:246. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang L., Schmalz C., Zhou J. Water Res. 2016;101:535. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public Swimming Pool and Spa Pool Advisory Document, North Sidney: Health Prot. NSW, 2013.

- 12.Westerhoff P., Chao P., Mash H. Water Res. 2004;38:1502. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X., Zhang X. Water Res. 2016;96:166. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosyakov D.S., Ul’yanovskii N.V., Popov M.S. Water Res. 2017;127:183. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosyakov D.S., Ul’yanovskii N.V., Popov M.S. J. Anal. Chem. 2018;73:1260. doi: 10.1134/S1061934818130099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebedev A.T. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007;13:51. doi: 10.1255/ejms.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vozhdaeva M.Yu., Kholova A.R., Melnitskiy I.A. Molecules. 2021;26:1852. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bujak I.T., Kralj M.B., Kosyakov D.S. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;74020:140131. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ul’yanovskii N.V., Kosyakov D.S., Sypalov S.A. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;805:150380. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brauer G. Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. New York: Academic; 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebedev A.T., Shaydullin G.M., Sinikova N.A. Water Res. 2004;38:3713. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurie, Yu.Yu., Spravochnik po analiticheskoi khimii (Handbook of Analytical Chemistry), Moscow: -Khimiya, 1989.