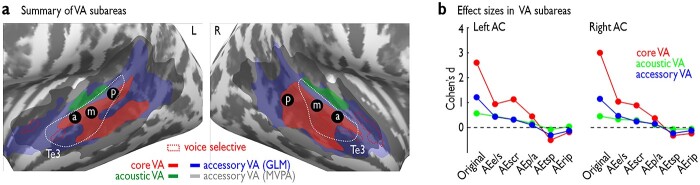

Fig. 4.

Summary of findings. a) Parcellation of the original VA into subfields based on their specificity for voice processing. The core VA (red) originating from the GLM interaction analysis (see Fig. 2b, green dashed line in the upper left panel) seems generic to voice processing since activity in these regions cannot be reduced to acoustic patterns in the comparison of voice and nonvoice sounds and their AEs. An acoustic VA (green) defined by the MVPA generalizations from original to AEs sounds (see Fig. 3b, green dashed line) seems to decode features that are relevant but not exclusive for voice from nonvoice discrimination. The accessory VA based on the GLM (blue; see Fig. 2a, black dashed line in left panels) and the MVPA approach (gray; see Fig. 3a, black dashed line) is only incidentally involved in voice processing. The dots denoted by a/m/p show the VA patches as previously defined (Pernet et al. 2015) that all uniformly are located within the core VA and that all seem to have a uniform function for generic voice processing. Red dashed line indicates potential voice-selective regions (see Fig. 2b). b) Effect size measures (Cohen’s d) for the 3 bilateral VA subareas (core VA, acoustic VA, accessory VA) in AC based on the group effect for comparing voice sounds (or their AEs) against nonvoice sounds (or their AEs). The bilateral core VA shows a highly increased effect size (Cohen’s d > 2.6) for original voice against nonvoice processing, which most likely originates from the interaction contrast effects shown in Fig. 2b.