Abstract

Background

Some multiple sclerosis (MS) disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) impair responses to vaccines, emphasizing the importance of understanding COVID-19 vaccine immune responses in people with MS (PwMS) receiving different DMTs.

Methods

This prospective, open-label observational study enrolled 45 participants treated with natalizumab (n = 12), ocrelizumab (n = 16), fumarates (dimethyl fumarate or diroximel fumarate, n = 11), or interferon beta (n = 6); ages 18–65 years inclusive; stable on DMT for at least 6 months. Responder rates, anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain IgG (anti-RBD) geometric mean titers (GMTs), antigen-specific T cells, and vaccination-related adverse events were evaluated at baseline and 8, 24, 36, and 48 weeks after first mRNA-1273 (Moderna) dose.

Results

At 8 weeks post vaccination, all natalizumab-, fumarate-, and interferon beta-treated participants generated detectable anti-RBD IgG titers, compared to only 25% of the ocrelizumab cohort. At 24 and 36 weeks post vaccination, natalizumab-, fumarate-, and interferon beta-treated participants continued to demonstrate detectable anti-RBD IgG titers, whereas participants receiving ocrelizumab did not. Anti-RBD GMTs decreased 81.5% between 8 and 24 weeks post vaccination for the non-ocrelizumab-treated participants, with no significant difference between groups. At 36 weeks post vaccination, ocrelizumab-treated participants had higher proportions of spike-specific T cells compared to other treatment groups. Vaccine-associated side effects were highest in the ocrelizumab arm for most symptoms.

Conclusions

These results suggest that humoral response to mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine is preserved and similar in PwMS treated with natalizumab, fumarate, and interferon beta, but muted with ocrelizumab. All DMTs had preserved T cell response, including the ocrelizumab cohort, which also had a greater risk of vaccine-related side effects.

Keywords: COVID-19, Dimethyl fumarate, Interferon beta, Multiple sclerosis, Natalizumab, Ocrelizumab, Vaccine response

Key Summary Points

| Certain disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) may impair immune responses to vaccines. |

| We evaluated responder rates, anti-SARS-CoV-2 RBD IgG titers, antigen-specific T cells, and adverse events following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in people with MS (PwMS) on various DMTs. |

| Humoral response to mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine was similar in PwMS treated with natalizumab, fumarate, and interferon beta, but muted with ocrelizumab. |

| T cell response to mRNA-1273 was similar with all DMTs evaluated, including ocrelizumab. |

| A trend toward greater risk of vaccine-related side effects was observed in the ocrelizumab cohort. |

Introduction

COVID-19 is a potentially fatal respiratory illness caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which has developed into the ongoing global pandemic [1, 2]. As of June 2022, over one million people in the USA and over six million worldwide have lost their lives to COVID-19 [2, 3]. Mass vaccination is one of the best tools available to curtail the pandemic [4]. In December 2020, two messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines, each demonstrating greater than 94% efficacy at preventing symptomatic COVID-19 infection, were authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration [5–7]. At the time of authorization, there were limited data regarding vaccine efficacy for individuals receiving immunosuppressant or immunomodulating medications.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common inflammatory, demyelinating, neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system, with an estimated prevalence of almost one million people in the USA [8, 9]. Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in people with MS (PwMS), identified in real-world registry studies, included older age, Black race, and cardiovascular comorbidities [10–12], similar to the general population. Many disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) used to treat PwMS alter the immune system [13], and previous studies have demonstrated that some DMTs impair immune response to vaccination [13–18]. In particular, anti-CD20 therapies result in a dramatic attenuation of the humoral immune response to vaccines, especially those utilizing novel antigens [19–22]. The spike glycoprotein mediates viral entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells [23]; therefore, antibodies against the spike glycoprotein are believed to be an important component of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and are detectable in more than 99% of patients with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-confirmed COVID-19 [24]. As such, both mRNA vaccines encode epitopes of the spike glycoprotein as the target immunogen [5, 6]. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain IgG (anti-RBD) antibodies can be readily measured using commercially available assays, allowing semi-quantitative assessment of humoral immunity following natural infection and vaccination [25]. The ability of vaccines to induce a coordinated induction of both humoral- and cell-mediated responses is important in preventing severe disease or death from SARS-CoV-2 infection in PwMS who are receiving immunotherapy [26].

Robust data across multiple DMTs with different mechanisms of action are needed to understand immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in PwMS. The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the effect of DMTs on the immune response to mRNA vaccines utilizing a single center, with uniform treatment, vaccination, and sample acquisition protocols. Our hypothesis, based on existing literature, was that PwMS treated with interferon beta, fumarates, or natalizumab would exhibit normal humoral responses to mRNA vaccines, whereas ocrelizumab treatment would result in relative blunting.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The recruitment goal for this prospective, open-label observational study was 120 participants, with 30 in each treatment arm. We included PwMS, aged 18–65 years old, who had been on their current DMT for at least 6 months: natalizumab (minimum of six doses), ocrelizumab (minimum of two full cycles), fumarates (including dimethyl fumarate [DMF] and diroximel fumarate [DRF]), or any interferon beta products (Fig. 1). DMT selection was limited to those most frequently used in our center, with all interferon beta products included to maximize recruitment in that treatment arm. For consistency, participation was limited to recipients of the Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine. A washout period of 12–20 weeks from last infusion was recommended for eligible participants receiving ocrelizumab. We excluded patients with known history of COVID-19 infection; concurrent intravenous or subcutaneous immunoglobulin treatment (including tixagevimab/cilgavimab); corticosteroids received within 30 days of first vaccine dose; lymphopenia (absolute lymphocyte count < 0.5 × 109/L); recent immunization with non-COVID vaccine (within 4 weeks); additional COVID-19 vaccine dose; and pregnancy or lactation. Participation fell short of the recruitment goal because many patients were ineligible at study initiation, having either received the vaccine more than 8 weeks prior or received the BioNTech/Pfizer BNT162b2b vaccine.

Fig. 1.

Study design. aIncluding dimethyl fumarate and diroximel fumarate. bAny interferon and peginterferon beta-1a. cMeasured using sCOVg, Siemens Healthineers. dMeasured using T cell receptor sequencing (ImmunoSEQ T-MAP COVID). Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain, DMT disease-modifying therapy, MS multiple sclerosis

Ethics

The study was conducted according to local regulations and in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964. All instructions, regulations, and agreements of the protocol, and applicable International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, were adhered to, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Barnabas Medical Center (Study Number 21-02). Patients were informed of the results of their antibody testing. Patients were advised about the recommended timing of vaccination within the course of routine clinical care with their MS specialist. As with a clinical trial, patients were made aware of the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Study Procedures

Eligible participants provided written informed consent. Participants had their demographics, medical history, and initial serum samples collected either (1) within 1 week of the first dose of the mRNA-1273 vaccine or (2) 8 weeks following the initial dose of mRNA-1273. Participants who received the mRNA-1273 vaccine prior to enrollment were screened for prior asymptomatic exposure to SARS-CoV-2 using a commercial anti-nucleocapsid assay (Abbott Architect, Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL). Post-vaccine serum collections were performed at 8 (± 1 week), 24 (± 2 weeks), 36 (± 2 weeks), and 48 (± 4 weeks) weeks from the initial vaccine dose. All serum samples were analyzed to assess anti-RBD IgG titers using a semi-quantitative commercial assay (Siemens Healthineers sCOVg assay, Tarrytown, NY) [27]. Antigen-specific T cells were assessed 36 weeks after the first dose of mRNA-1273 using T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing (ImmunoSEQ T-MAP COVID, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Seattle, WA), which aligns TCR sequences to a library of TCR clones enriched in convalescent patients who were naturally infected with SARS-CoV-2. Spike-specific TCR templates were used to compare T cell responses between groups.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was geometric mean titers (GMTs) of anti-RBD IgG at 8 weeks from initial vaccine dose. Given that previous observational studies have found that interferon beta treatments do not reduce antibody titers following vaccination, this treatment arm was used as the reference group for comparison of anti-RBD titers [14, 28, 29]. Secondary outcome measures included comparison of GMTs at subsequent time points, assessment of spike-specific T cells, proportion of participants with a fourfold and twofold increase in anti-RBD titer from baseline, and any detectable anti-RBD IgG.

Exploratory analyses included vaccine-related adverse events reported using a pre-defined questionnaire at the week 8 study visit; breakthrough COVID-19 infections confirmed by reverse transcription PCR or antigen testing; and the correlation between duration of current DMT use and GMT for each treatment. All serum samples were tested for anti-nucleocapsid IgG as a screen for asymptomatic exposure to SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Demographics were compared using either chi-square (categorical variables) without multiple comparisons or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; continuous variables) with multiple comparisons when overall p < 0.05. GMT values were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons. Anti-RBD value of 0.5 (50% of the lower limit of detection) was imputed for specimens below the lower limit of detection or when no baseline serum was collected. The response rates and GMTs for each time point for each treatment were summarized. Differences in response rates between groups were analyzed using a chi-square test.

Results

Participants

As of December 6, 2021, we enrolled 45 participants in the following treatment groups: natalizumab (n = 12), ocrelizumab (n = 16), fumarates (n = 11 [10 DMF and 1 DRF]), and interferon beta (n = 6). Table 1 reports the baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the study cohort according to DMT. Overall, 82% were female, with a mean (SD) age of 49 (11) years across all participant groups. The only statistically significant imbalances between treatment groups were race and duration of exposure to current DMT. The imbalance was a consequence of a lack of racial heterogeneity in the ocrelizumab group, and significantly longer interferon beta exposure relative to other treatments.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics

| Ocrelizumab | Natalizumab | Fumarate | Interferon beta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 12 | 11 | 6 | |

| Age, mean ± SD (range), years | 52.6 ± 7.3 (38–64) | 42.9 ± 13.7 (20–59) | 48.5 ± 11.5 (27–62) | 50.2 ± 9.3 (40–65) | 0.135 |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (75.0) | 10 (83.3) | 10 (90.9) | 5 (83.3) | 0.764 |

| Racea | |||||

| White, n (%) | 16 (100) | 5 (50) | 6 (67) | 3 (50) | 0.015 |

| Black, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (50) | 3 (33) | 3 (50) | 0.015 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 32.8 ± 9.9 | 27.3 ± 6.2 | 27.3 ± 4.1 | 27.0 ± 6.4 | 0.112 |

| Time since MS onset, mean ± SD (range), years | 16.3 ± 7.3 (4.5–29.4) | 14.3 ± 12.3 (2.4–39.2) | 15.8 ± 9.5 (4.1–33.2) | 10.6 ± 4.6 (5.2–17.2) | 0.603 |

| Time since MS diagnosis, mean ± SD (range), years | 10.5 ± 8.1 (2.2–24.4) | 10.8 ± 9.5 (1.4–26.1) | 12.8 ± 9.2 (3.1–30.2) | 10.1 ± 5.0 (5.2–17.2) | 0.721 |

| EDSS score, mean ± SD (range)a | 2.8 ± 1.6 (1.5–6.0) | 1.9 ± 1.2 (1.0–4.5) | 2.1 ± 0.5 (1.5–3.0) | 2.5 ± 1.1 (1.5–4.0) | 0.445 |

| Duration of DMT exposure, mean ± SD (range), months | 27.3 ± 8.7 (16–42) | 51.2 ± 50.8 (10–185) | 49.8 ± 35.1 (12–95) | 108 ± 54.1 (61–206) | 0.0007b |

| DMT washout, mean ± SD (range), days | 129.8 ± 34.1 (83–192) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Statistical analysis was one-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons against all groups when overall p < 0.05, or chi-square (categorical variables) without multiple comparisons

DMT disease-modifying therapy, EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MS multiple sclerosis, N/A not available

aData not available for all participants

bParticipants receiving interferon beta therapy had a longer duration of DMT exposure

Post-vaccination Anti-RBD IgG Levels by DMT

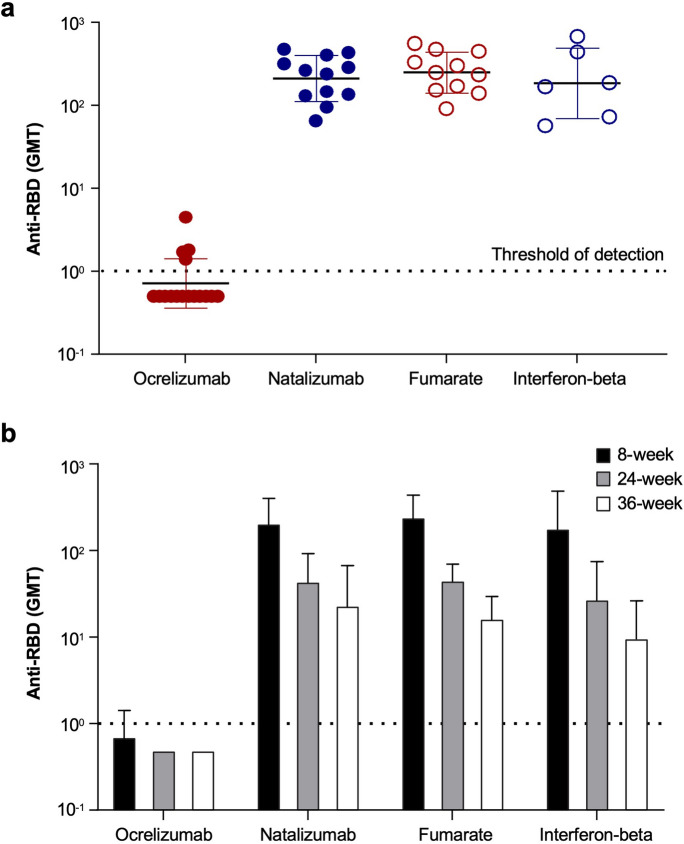

At the 8-week post-vaccination time point, all natalizumab-, fumarate-, and interferon beta-treated participants generated detectable anti-RBD IgG titers. There was no difference in GMTs between these three treatment arms. However, in the ocrelizumab-treated participant cohort, only 25% of participants had detectable anti-RBD IgG titers (Table 2) and titers were found to be significantly lower than the other treatment arms (Fig. 2). Only one (6.25%) participant receiving ocrelizumab had a fourfold or greater increase in anti-RBD titer from baseline, and only four (25%) had a twofold increase.

Table 2.

Anti-RBD IgG levels at 8 weeks post initial vaccine dose

| Ocrelizumab | Natalizumab | Fumarate | Interferon beta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8-Week analysis | |||||

| n | 16 | 12 | 11 | 6 | |

| Anti-RBD GMT ± geometric SD | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 210.3 ± 1.9 | 248.4 ± 1.8 | 184.0 ± 2.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Any detectable anti-RBD IgG, n (%) | 4 (25) | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 6 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| > Twofold increase, n (%) | 4 (25) | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 6 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| > Fourfold increase, n (%) | 1 (6.3) | 12 (100) | 11 (100) | 6 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| 24-Week analysis | |||||

| n | 4 | 10 | 9 | 6 | |

| Anti-RBD GMT ± geometric SD | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 44.8 ± 2.1 | 46.2 ± 1.5 | 27.8 ± 2.7 | 0.012 |

| > Twofold increase, n (%) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 9 (100) | 6 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| > Fourfold increase, n (%) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 9 (100) | 6 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| 36-Week analysis | |||||

| n | 8a | 7 | 8 | 4 | |

| Anti-RBD GMT ± geometric SD | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 23.7 ± 2.8 | 16.7 ± 1.8 | 10.0 ± 2.7 | 0.008 |

| > Twofold increase, n (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | < 0.0001 |

| > Fourfold increase, n (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (100) | 8 (100) | 4 (100) | < 0.0001 |

GMT values were compared using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons

Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain, GMT geometric mean titer

aTwo participants in the ocrelizumab cohort received prophylactic tixagevimab/cilgavimab to prevent COVID-19 infections and were therefore excluded from 36-week anti-RBD GMT analyses because of cross-reactivity

Fig. 2.

Anti-RBD IgG levels at a 8 weeks post initial vaccine dose and b 8, 24, and 36 weeks post initial vaccine dose. Anti-RBD IgG were quantified by Siemens Healthineers’ SARS-CoV-2 IgG (sCOVg) assay at a 8 weeks and b 8, 24, and 36 weeks post initial vaccine dose. The dotted line indicates the threshold of detection. Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain, GMT geometric mean titer

At 24 weeks post vaccination, all natalizumab-, fumarate-, and interferon beta-treated participants continued to have detectable anti-RBD IgG titers compared with no (0%) ocrelizumab-treated participants (Table 2). Overall anti-RBD GMTs for non-ocrelizumab-treated participants decreased from 217.9 to 40.4 (arbitrary units) between 8 and 24 weeks, an 81.5% reduction. There were no significant differences in GMTs between these groups at 24 weeks. These trends continued through to 36 weeks post vaccination, when all DMT groups except ocrelizumab had detectable anti-RBD IgG titers (Table 2). No statistical analysis was performed at the planned 48-week interval because most samples were excluded for one of the following reasons: administration of additional vaccine doses, SARS-CoV-2 exposure, or monoclonal antibody treatment.

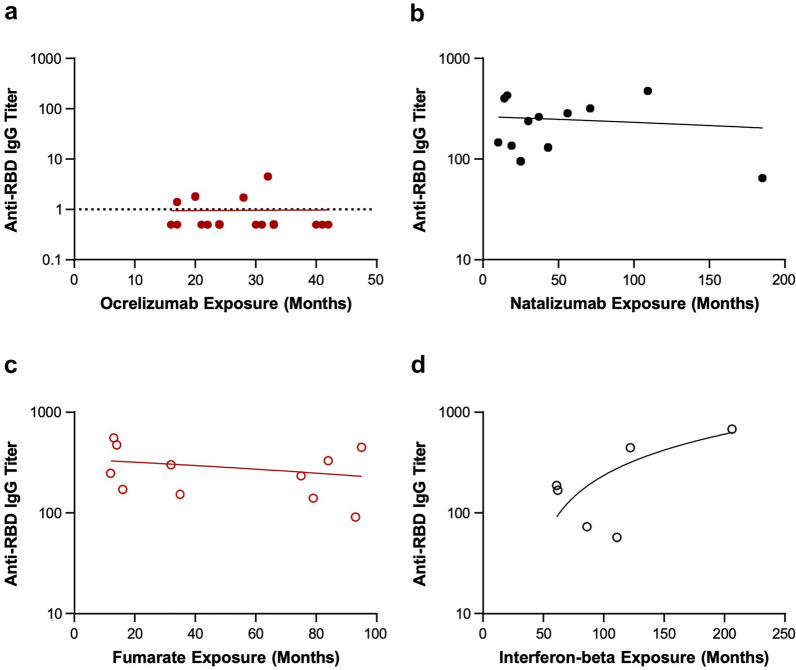

Correlation of Post-vaccination Anti-RBD IgG Levels with Treatment Duration

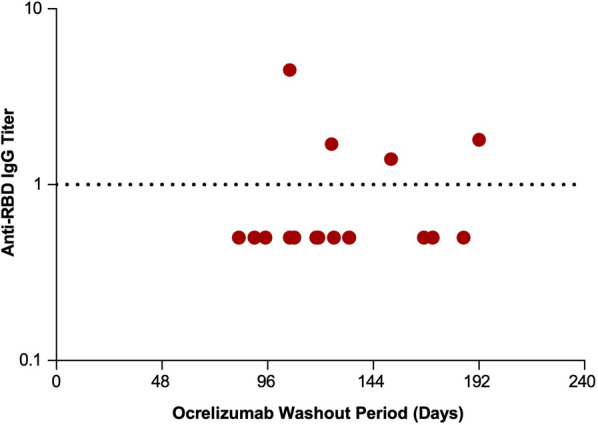

Duration of ocrelizumab, natalizumab, and fumarate treatment did not correlate with anti-RBD titer (Fig. 3 and Table 3). We did observe a positive correlation between duration of interferon beta treatment and anti-RBD titer (p = 0.042) but these findings should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size. No correlation was observed between ocrelizumab washout duration and anti-RBD titer (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Anti-RBD IgG titer by duration of treatment. Anti-RBD is shown by duration of a ocrelizumab, b natalizumab, c fumarate, and d interferon beta treatment. Anti-RBD IgG were quantified by Siemens Healthineers’ SARS-CoV-2 IgG (sCOVg) assay at 8 weeks post initial vaccine dose. The dotted line indicates the threshold of detection. Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain. aOcrelizumab Y-axis differs from other DMTs.

Table 3.

Anti-RBD IgG titer by duration of treatment

| r | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Ocrelizumab duration vs. anti-RBD IgG titer | 0.009 | 0.973 |

| Natalizumab duration vs. anti-RBD IgG titer | − 0.122 | 0.707 |

| Fumarate duration vs. anti-RBD IgG titer | − 0.278 | 0.408 |

| Interferon beta duration vs. anti-RBD IgG titer | 0.828 | 0.042 |

Geometric mean titer values were compared using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons

Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain

Fig. 4.

Anti-RBD IgG titer by ocrelizumab washout period. Anti-RBD is shown by duration of time since the last dose (washout period) of ocrelizumab. Anti-RBD IgG were quantified by Siemens Healthineers’ SARS-CoV-2 IgG (sCOVg) assay at 8 weeks post initial vaccine dose. The dotted line indicates the threshold of detection. Anti-RBD IgG SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain

Post-vaccination Cell-Mediated Responses by DMT

Participants treated with natalizumab had a higher absolute number of T cells at 36 weeks post vaccination than participants treated with ocrelizumab, fumarates, or interferon beta (Table 4), an expected finding based on the mechanism of action. However, participants treated with ocrelizumab showed a higher proportion of spike-specific T cells, relative to participants in the other DMT groups, at 36 weeks post vaccination (Table 4 and Fig. 5).

Table 4.

T cell analyses at 36 weeks post vaccination

| Ocrelizumab | Natalizumab | Fumarate | Interferon beta | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 7a | 5b | 3b | |

| T cells per sample, mean ± SD | 150,639 ± 57,275 | 234,587 ± 38,830 | 122,911 ± 82,295 | 137,531 ± 23,885 | 0.03 |

| Spike-specific T cells per sample, mean ± SD | 943.9 ± 486.2 | 551.0 ± 237.7 | 195.8 ± 156.6 | 174.0 ± 21.1 | 0.003 |

| Proportion of spike-specific T cells, mean ± SD | 0.0065 ± 0.0029 | 0.0024 ± 0.0012 | 0.0015 ± 0.0003 | 0.0013 ± 0.0001 | 0.0003 |

Antigen-specific T cells were assessed using T cell receptor (TCR) sequencing (ImmunoSEQT-MAP COVID, Adaptive Biotechnologies) at 36 weeks after the first dose of mRNA-1273. Spike-specific TCR templates were used to compare T cell responses between groups

aTwo samples were excluded owing to asymptomatic COVID-19

bThe fumarate and interferon beta groups had fewer T cell samples because additional consent required for T cell testing was not obtained for the excluded participants

Fig. 5.

T cell responses 36 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in people with MS (PwMS) treated with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). Proportion of spike-specific T cells is shown 36 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in PwMS treated (> 6 months) with ocrelizumab, natalizumab, fumarate, or interferon beta DMT

Safety

No anaphylactic events or life-threatening responses occurred after the first or second doses of the mRNA-1273 vaccine in our participant cohorts. The most commonly reported adverse events were injection site pain and fatigue. Ocrelizumab-treated participants were more likely to experience myalgias following vaccination (p < 0.05), with a trend toward higher rates of all side effects except injection site pain (Table 5).

Table 5.

Vaccine side effects at 8 weeks from initial dose

| Ocrelizumab | Natalizumab | Fumarate | Interferon beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All side effects, n (%) | 15 (93.8) | 9 (75.0) | 10 (90.9) | 6 (100.0) |

| Injection site pain | 12 (75.0) | 7 (58.3) | 8 (72.7) | 5 (83.3) |

| Fatigue | 14 (87.5) | 7 (58.3) | 6 (54.5) | 4 (66.7) |

| Headache | 9 (56.3) | 5 (41.7) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Myalgia* | 11 (68.8) | 2 (16.7) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (33.3) |

| Arthralgia | 7 (43.8) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fever | 7 (43.8) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Chills | 8 (50.0) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (33.3) |

Comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s correction for multiple comparisons

*Statistical significance of p < 0.05

Vaccine Efficacy

None of the serum samples collected at 8 or 24 weeks had detectable anti-nucleocapsid IgG, indicating neither breakthrough COVID-19 nor asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 exposure during those post-vaccination intervals. No known breakthrough COVID-19 infections were reported or detected until the 36-week analysis, at which time two asymptomatic exposures were identified. Twelve symptomatic COVID-19 infections (four ocrelizumab; four natalizumab; three fumarate; one interferon beta) were reported between 36-week and 48-week sample collections, corresponding to the emergence of the Omicron variant.

Discussion

Our study evaluated the effect of DMTs on the humoral response to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in PwMS using a quantitative measurement of anti-RBD IgG with a strong correlation with serum neutralizing activity [27]. All participants in the natalizumab-, fumarate-, and interferon beta-treated arms generated a humoral immune response to the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine, which persisted at lower levels up to 36 weeks after the initial dose. Although similar GMTs were noted in the natalizumab, fumarates, and interferon beta treatment groups, we observed dramatically reduced anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers in the ocrelizumab-treated group, as observed in other studies [12, 18, 21, 30], with most ocrelizumab-treated participants having no detectable anti-RBD antibodies.

Our results fit with the study hypothesis and the findings of the ocrelizumab VELOCE study, which found attenuated humoral responses to tetanus toxoid and dramatic muting with novel antigens (keyhole limpet hemocyanin) [20]. Anti-CD20 medications, including ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and off-label rituximab, act by depleting circulating B lymphocytes [21], and many patients receiving ocrelizumab therapy fail to develop antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 following natural infection and recovery from COVID-19 [31]. In a recent study, PwMS treated with anti-CD20 DMT had reduced B cell functional responses, poor generation of antigen-specific memory B cells, and low antibody responses to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine [21]. In other studies, PwMS treated with anti-CD20 DMTs or fingolimod have had a lower antibody response following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination [18, 32, 33]. In the present study, no correlation was observed between length of time of treatment with an anti-CD20 DMT and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination response, whereas Sabatino et al. observed a negative correlation between SARS-CoV-2 vaccination response and duration of anti-CD20 DMT [33]. The reasons for this discrepancy are not known but it may be related to the shorter median time and smaller range on anti-CD20 DMTs in this study (27.3 [16–42] months vs. median of 33.4–45.7 months in Sabatino et al.). In addition, PwMS treated with anti-CD20 DMTs are at an increased risk of more severe COVID-19 [12]. Of patients treated with rituximab, only 49% showed humoral responses and 32% generated a cell-mediated response after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, compared with 100% and 88% in healthy controls, respectively [34]. A recent meta-analysis and systemic review of nearly all US Food and Drug Administration-approved DMTs corroborated lower B cell response in PwMS treated with anti-CD20 and lower T cell response in interferon-treated PwMS, and demonstrated reduced COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in those treated with S1PRM and anti-CD20 [35]. Limitations of prior studies include differences in DMTs, differences in vaccination and treatment protocols, and disparate geographic area.

Failure to demonstrate a correlation between ocrelizumab washout duration and anti-RBD titer was presumably a consequence of sample size and relatively short washout periods. Although the time since last anti-CD20 treatment was positively predictive of a humoral vaccine response in previous studies [18, 21, 32], some with longer median washout periods [34], no correlation has been observed in others despite washout periods of up to 10 months [33].

T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination were found to be varied across the different DMT groups in this study, with natalizumab-treated participants showing the highest mean numbers of T cells, but ocrelizumab-treated participants displaying the highest proportion of spike-specific T cells in response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Interestingly, several other studies have also demonstrated that PwMS receiving ocrelizumab DMT have an attenuated humoral response but preserved T cell response [36–38].

In PwMS, injection site pain, fatigue, and headache are common COVID-19 vaccine side effects [30], similar to our observations. The overall rate of vaccine side effects was high (75–100%); ocrelizumab-treated participants experienced significantly more reports of myalgia with mRNA-1273 compared with those treated with natalizumab, fumarates, or interferon beta. As of the 24-week time point, no breakthrough COVID-19 infections were reported in the study participants and there were no indications of asymptomatic cases. Since then, as the Omicron variant has become widespread, at least 14 breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 cases have been reported. Of those, 12 were symptomatic (four in participants treated with natalizumab, four in participants treated with ocrelizumab, three in participants treated with fumarates, and one in participants treated with interferon beta), as well as two asymptomatic cases in participants treated with natalizumab.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study, including sample size. Our recruitment goal was not met owing to several factors, including vaccine hesitancy and the exclusion of BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine recipients and patients vaccinated more than 8 weeks prior to initiation of the study. Cellular immunity was not evaluated as part of the 8-week interim analysis, although vaccine-specific T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 was subsequently evaluated from 36 weeks post vaccination. The relative importance of both humoral and cell-mediated mechanisms in protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in the context of DMTs is not yet fully understood; this will be crucial to identify, especially for PwMS who failed to seroconvert. The study was not powered to address clinical efficacy of the Moderna vaccine in specific treatment arms, and not all MS DMTs were evaluated.

Conclusion

These results suggest that humoral response to mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination is preserved in PwMS treated with natalizumab, fumarates, and interferon beta, but not ocrelizumab. Clinical data are needed to confirm the impact of the attenuated immune response. The benefit of treatment interruption or postponing ocrelizumab for the purpose of immunization should be considered and weighed against the risk posed by withholding treatment for multiple sclerosis. Findings from our study provide healthcare practitioners with additional quantitative data on the immune response to mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in PwMS treated with various DMTs.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Biogen (Cambridge, MA, USA). Karen Spach, PhD and Joseph E. Druso, PhD of Excel Scientific Solutions (Fairfield, CT, USA) provided initial editing support based on a draft from authors and incorporated author comments during revisions, and Miranda Dixon from Excel Scientific Solutions copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements: funding was provided by Biogen.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee were funded by Biogen (Cambridge, MA, USA). Funding for writing and editorial support was provided by Biogen.

Author’ Contributions

Study conception and design: Matthew A. Tremblay, Jason P. Mendoza, Robin L. Avila. Data collection: Aliya Jaber, Meera Patel, Andrew Sylvester, Mary Yarussi, Matthew A. Tremblay. Writing of manuscript: Matthew A. Tremblay, Jason P. Mendoza, Robin L. Avila. Intellectual content and manuscript approval: all authors.

Disclosures

Aliya Jaber, Meera Patel, and Mary Yarussi declare that they have no conflict of interest. Andrew Sylvester receives consulting and/or speaker fees from Alexion, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Genentech. J. Tamar Kalina, Jason P. Mendoza, and Robin L. Avila are employees of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Biogen. Matthew A. Tremblay receives research funding support from Biogen, consulting fees for medical advisory boards from Biogen, Genentech, TG Therapeutics, and speaker fees from Genentech.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The study was conducted according to local regulations and in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964. All instructions, regulations, and agreements of the protocol, and applicable International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, were adhered to, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Barnabas Medical Center (Study Number 21-02). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. No patient-level identifying information is included in this manuscript.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Versions of these tables and figures were previously presented as a platform presentation at CMSC (2021) Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers 2021 Annual Meeting (Oct 25–28, 2021 in Orlando, FL, USA) and as a poster at CMSC (2022) Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers 2022 Annual Meeting (Jun 1–4, 2022 in National Harbor, MD, USA).

References

- 1.Miller IF, Becker AD, Grenfell BT, Metcalf CJE. Disease and healthcare burden of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1212–1217. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0952-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 2021. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html. Accessed 2021 Sept 30.

- 3.World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard 2021. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 2021 Sept 30.

- 4.Woopen C, Schleußner K, Akgün K, Ziemssen T. Approach to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:701752. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.701752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shilo S, Rossman H, Segal E. Signals of hope: gauging the impact of a rapid national vaccination campaign. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(4):198–199. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MS International Federation. Atlas of MS. https://www.atlasofms.org/map/global/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms. Accessed 9 Dec 2022.

- 9.Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029–e1040. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salter A, Fox RJ, Newsome SD, et al. Outcomes and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a North American Registry of patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(6):699–708. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sormani MP, Salvetti M, Labauge P, et al. DMTs and Covid-19 severity in MS: a pooled analysis from Italy and France. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8(8):1738–1744. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sormani MP, De Rossi N, Schiavetti I, et al. Disease-modifying therapies and coronavirus disease 2019 severity in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(4):780–789. doi: 10.1002/ana.26028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciotti JR, Valtcheva MV, Cross AH. Effects of MS disease-modifying therapies on responses to vaccinations: a review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;45:102439. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olberg HK, Cox RJ, Nostbakken JK, et al. Immunotherapies influence the influenza vaccination response in multiple sclerosis patients: an explorative study. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1177/1352458513513970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olberg HK, Eide GE, Cox RJ, et al. Antibody response to seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving immunomodulatory therapy. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(3):527–534. doi: 10.1111/ene.13537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kappos L, Mehling M, Arroyo R, et al. Randomized trial of vaccination in fingolimod-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84(9):872–879. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guerrieri S, Lazzarin S, Zanetta C, Nozzolillo A, Filippi M, Moiola L. Serological response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod or ocrelizumab: an initial real-life experience. J Neurol. 2022;269(1):39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Achiron A, Mandel M, Dreyer-Alster S, et al. Humoral immune response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2021;14:17562864211012835. doi: 10.1177/17562864211012835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bingham CO, 3rd, Looney RJ, Deodhar A, et al. Immunization responses in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with rituximab: results from a controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):64–74. doi: 10.1002/art.25034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bar-Or A, Calkwood JC, Chognot C, et al. Effect of ocrelizumab on vaccine responses in patients with multiple sclerosis: the VELOCE study. Neurology. 2020;95(14):e1999–e2008. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apostolidis SA, Kakara M, Painter MM, et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis on anti-CD20 therapy. Nat Med. 2021;27:1990–2001. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01507-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Disanto G, Sacco R, Bernasconi E, et al. Association of disease-modifying treatment and anti-CD20 infusion timing with humoral response to 2 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:1529–1530. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du L, He Y, Zhou Y, et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wajnberg A, Amanat F, Firpo A, et al. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science. 2020;370(6521):1227–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.abd7728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyriakidis NC, Lopez-Cortes A, Gonzalez EV, Grimaldos AB, Prado EO. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: a comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):28. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00292-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tortorella C, Aiello A, Gasperini C, et al. Humoral- and T-cell-specific immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with MS using different disease-modifying therapies. Neurology. 2022;98(5):e541. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siemens-healthineers. Atellica IM SARS-CoV-2 IgG (sCOVG) Instructions for Use, 11207507_EN Rev. 01, 2021–03 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/146931/download. Accessed 24 June 2021.

- 28.Schwid SR, Decker MD, Lopez-Bresnahan M, Rebif-Influenza Vaccine Study I Immune response to influenza vaccine is maintained in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving interferon beta-1a. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1964–1966. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000188901.12700.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwid SR, Thorpe J, Sharief M, et al. Enhanced benefit of increasing interferon beta-1a dose and frequency in relapsing multiple sclerosis: the EVIDENCE study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(5):785–792. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Achiron A, Dolev M, Menascu S, et al. COVID-19 vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis: what we have learnt by February 2021. Mult Scler. 2021;27(6):864–870. doi: 10.1177/13524585211003476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iannetta M, Landi D, Cola G, et al. T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in multiple sclerosis patients treated with ocrelizumab healed from COVID-19 with absent or low anti-spike antibody titers. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;55:103157. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tallantyre EC, Vickaryous N, Anderson V, et al. COVID-19 vaccine response in people with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2022;91:89–100. doi: 10.1002/ana.26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabatino JJ Jr, Mittl K, Rowles WM, et al. Multiple sclerosis therapies differentially affect SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced antibody and T cell immunity and function. JCI Insight. 2022;7(4):e156978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Moor MB, Suter-Riniker F, Horn MP, et al. Humoral and cellular responses to mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with a history of CD20 B-cell-depleting therapy (RituxiVac): an investigator-initiated, single-centre, open-label study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3(11):e789–e797. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(21)00251-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Etemadifar M, Nouri H, Pitzalis M, et al. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies and COVID-19 vaccines: a practical review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(9):986–994. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2022-329123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brill L, Rechtman A, Zveik O, et al. Humoral and T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(12):1510–1514. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katz JD, Bouley AJ, Jungquist RM, et al. Humoral and T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in multiple sclerosis patients treated with ocrelizumab. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57:103382. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Räuber S, Korsen M, Huntemann N, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in relation to peripheral immune cell profiles among patients with multiple sclerosis receiving ocrelizumab. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93:978–985. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-328197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Versions of these tables and figures were previously presented as a platform presentation at CMSC (2021) Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers 2021 Annual Meeting (Oct 25–28, 2021 in Orlando, FL, USA) and as a poster at CMSC (2022) Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers 2022 Annual Meeting (Jun 1–4, 2022 in National Harbor, MD, USA).