Abstract

Carbapenems are considered last-resort antibiotics for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Although the main mechanism of carbapenem-resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the loss of OprD porin, carbapenemases continue to be a problem worldwide. The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of phenotypic tests (Carba NP, Blue Carba, and mCIM/eCIM) for detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. in Brazil. One hundred twenty-seven Pseudomonas spp. clinical isolates from different Brazilian states were submitted to phenotypic and molecular carbapenemase detection. A total of 90 carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa and 5 Pseudomonas putida (35, blaVIM-2; 17, blaSPM-1; 2, blaIMP-10; 1, blaVIM-24; 1, blaNDM-1; 39, blaKPC-2). The phenotypic Carba NP, Blue Carba, and mCIM/eCIM showed sensitivity of 94.7%, 93.6%, and 93.6%, and specificity of 90.6%, 100%, and 96.8%, respectively. However, only the Carba NP presented the highest sensitivity and showed the ability in differentiating the carbapenemases between class A and class B using EDTA. Blue Carba failed to detect most of the class B carbapenemases, having the worst performance using EDTA. Our results show changes in the epidemiology of the spread of carbapenemases and the importance of their detection by phenotypic and genotypic tests. Such, it is essential to use analytical tools that faithfully detect bacterial resistance in vitro in a simple, sensitive, rapid, and cost-effective way. Much effort must be done to improve the current tests and for the development of new ones.

Keywords: Carbapenemase, Blue Carba, CarbaNP, mCIM/eCIM, Pseudomonas spp

Introduction

The carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria is a major concern for healthcare institutions. The resistance profile is used to choose antimicrobial therapy and the resistance mechanism for epidemiological purposes. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most well-known pathogen affecting healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), infections caused by carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa is classified as critical infections [1]. The development of carbapenem resistance among P. aeruginosa strains (CR-Pa) is multifactorial. CR-Pa mechanisms may be non-carbapenemase (non-CR-Pa) and include mutational ones such as membrane alteration (e.g., oprD), efflux system (e.g., MexAB-oprN), target site alteration, and increased chromosomal cephalosporinase activity [2]. Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of CR-Pa producing carbapenemase is serious concern given the rapid spread of mobile genetic elements among strains, particularly in Brazil [3, 4]. Carbapenemases are classified in Ambler class A (e.g., KPC), class B (e.g., IMP, VIM, NDM, SPM), and class D (OXAs) [5]. Although the most common type of carbapenemases in Pseudomonas spp. is class B (metallo-β-lactamase, MBL), class A can also be detected. Furthermore, epidemiological distribution of carbapenemases may vary between countries and geographic regions [6]. The detection of carbapenemase production is essential for epidemiological or infection-control purposes [3]. Additionally, new antimicrobials with no activity against class B producers, such as ceftazidime/avibactam and imipenem‐relebactam, bring the importance of detection and differentiation of these carbapenemases. Studies show that early notification of carbapenemase helps to target empirical therapy, leading to more effective treatment and less selective pressure for the emergence of antimicrobial resistance [7].

Rapid detection of carbapenemase is not easy. Molecular techniques such as PCR and sequencing are the gold standard but are expensive, and require specific equipment and trained personnel. In this context, non-molecular methods or phenotypic tests gain space for the cost–benefit. Phenotypic tests were developed according to need, which includes the type of carbapenemase and the most prevalent species, varying according to epidemiology. Several tests have been developed and validated, mostly for Enterobacterales. However, validation studies are required for Pseudomonas spp., especially for P. aeruginosa [8]. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the sensitivity of mCIM/eCIM, Carba NP, and Blue Carba phenotypic tests with PCR genotypic detection to differentiate between class A and class B by adding different EDTA concentrations in Pseudomonas spp. clinical isolates recovered from different Brazilian states.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 127 non-duplicate Pseudomonas spp. clinical isolates, including 122 P. aeruginosa and 5 Pseudomonas putida, showing decreased susceptibility to imipenem and/or meropenem by disk (10 µg) according CLSI breakpoints were studied. All strains were accessed from the collection of the Laboratório de Pesquisa em Infecção Hospitalar (LAPIH-IOC/Fiocruz). These isolates were recovered from nine Brazilian states during the years 2008 to 2019, from different clinical specimens (blood, urine, tracheal aspirate, rectal swab, catheter tip, and skin). Minimal inhibitory concentrations of meropenem and imipenem was determined using Etest strips (bioMérieux, La Balme-les-Grottes, France) on Mueller–Hinton agar plates at 37 °C, and the results were interpreted according to CLSI 2021 (M100).

The carbapenemase genes were previously characterized by PCR and sequencing for blaKPC [4], blaIMP, blaVIM, blaNDM [9], and blaSPM [10]. All results obtained from the sequencing were compared with the allelic variants the carbapenemases using the Geneious v.1.6.8 (Biomatters Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) and BLAST tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Among 122 P. aeruginosa isolates, 32 were negative for all carbapenemase genes investigated, 54 P. aeruginosa carried class B genes: blaVIM-2 (n = 33), blaSPM-1 (n = 17), blaIMP-10 (n = 2), blaVIM-24 (n = 1), blaNDM-1 (n = 1), and 36 class A: blaKPC-2. For P. putida isolates, three isolates carried blaKPC-2 and two blaVIM-2.

Phenotypic tests for detection of carbapenemase production

Carba NP

Carba NP test was performed as described by Dortet (2012) [11] with some modifications. A calibrated loop (10 µl) containing a recent growth on nutrient agar was inoculated in 500 μl of B-PER II bacterial lysis solution (Thermo Scientific, USA) followed by vortexing and incubation for 15 min at room temperature. Carba NP was performed in a 96-well plate. The phenol red solution 0.5%, containing 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (pH 7.8), was prepared in-house. The first well contains 100 µl of phenol red solution, the second the phenol red solution plus 6 mg/ml imipenem (Tienam ® Merck, Elkto, EUA), and the third, the phenol red solution with 6 mg/ml imipenem and EDTA (10 mM). After, 30 µl of bacterial lysis solution was added in the tree wells. The 96-well plates were incubated at 37 °C and visually read at 15, 30, 45, 60, and 120 min. The interpretation is as follows: A color change from red to yellow/orange in solutions containing imipenem indicated carbapenemase production, while solutions remaining red/reddish-orange were considered negative. Class B carbapenemases (MBLs) were differentiated by inhibiting the hydrolysis of imipenem in the solution containing EDTA and no color change.

Blue Carba

Blue Carba test was performed as described by Pires (2013) [12] with some modifications. A calibrated loop (10 µl) containing a recent growth on nutrient agar was directly applied in three wells of a 96-well plate containing 100 µl of bromothymol blue solution 0.04% (pH 7) prepared in-house, in three conditions: bromothymol blue solution only, bromothymol blue solution plus 6 mg/ml imipenem (Tienam ® Merck, Elkto, EUA), and bromothymol blue solution with 6 mg/ml imipenem and EDTA (0.1 mM). The assay was incubated at 37 °C and visualization was performed at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. The interpretation was as follows: A color change from blue to green or yellow in solutions containing imipenem was considered positive. Class B carbapenemases were differentiated by inhibiting the hydrolysis of imipenem in the well containing EDTA and no color change. This test was performed with four different EDTA concentrations (0.1 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, and 40 mM) to investigate the best concentration for visualization of MBL inhibition.

mCIM/eCIM

mCIM/eCIM tests were performed as described by CLSI 2021 (M100). Briefly, A loop (10 µl) with a recent growth in nutrient agar was inoculated in trypticase soy broth (TSB) with a disk of meropenem (10 µg) (oxoid), vortexed for 10–15 s and incubated at 35 °C for 4 h. The disk was then placed on the Mueller Hinton agar seeded with a 0.5 Mc Farland suspension of Escherichia coli ATCC25922 and incubated at 35° for 18–24 h. For eCIM, the same procedure was performed adding EDTA 0.5 mM (pH 8) to another TSB broth (eCIM). The interpretation follows the disk diameter measurement: 6–15 mm or 16–18 mm with small colonies was considered positive for carbapenemase production, ≥ 19 mm was negative. A 5-mm increase of the disk of eCIM in relation to the disk of mCIM suggests a presence of class B.

Statistical analyses

All results were interpreted blindly by 2 independent microbiologists. The tests were calculated by comparing the results of the phenotypic tests for class A and class B with the PCR/sequencing. Furthermore, the specificity, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated [13]. All phenotypic tests were performed twice, in case of disagreement with the genotypic test or in case of disagreement between microbiologists. Negative controls (E. coli ATCC 25,922 and P. aeruginosa PAO1) and positive controls (KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae CCBH 4556, NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae CCBH 16,302, and SPM-1 producing P. aeruginosa CCBH 4851) were included for all tests. The positive controls belonging to the Culture Collection of Hospital-Acquired Bacteria (CCBH-IOC), which is affiliated to the World Federation for Culture Collections, WFCC–WDCM 947, were phenotypically characterized by MIC determination, CARBA NP, Blue Carba, mCIM/eCIM, and genotypically by WGS (data not show).

Results

Except for one isolate (MIC = 1.5 µg/ml), all carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. (n = 95) showed mic > 32 µg/ml for imipenem and meropenem. Among carbapenemase-gene negative isolates (n = 32), 84.3% showed resistance to imipenem and meropenem, with mic > 32 µg/ml.

All phenotypic tests were able to identify the carbapenemase-production, regardless of the type of carbapenemase (class A or class B). The sensitivity of Carba NP, Blue-Carba, and mCIM in detecting carbapenemase was 94.7%, 93.6%, and 93.6%; the specificity was 90.6%, 100%, and 96.8%, respectively. The VPP was 96.7%, 100%, and 98.8% and VPN was 85.9%, 84.2%, and 83.7% for Carba NP, Blue-Carba, and mCIM, respectively.

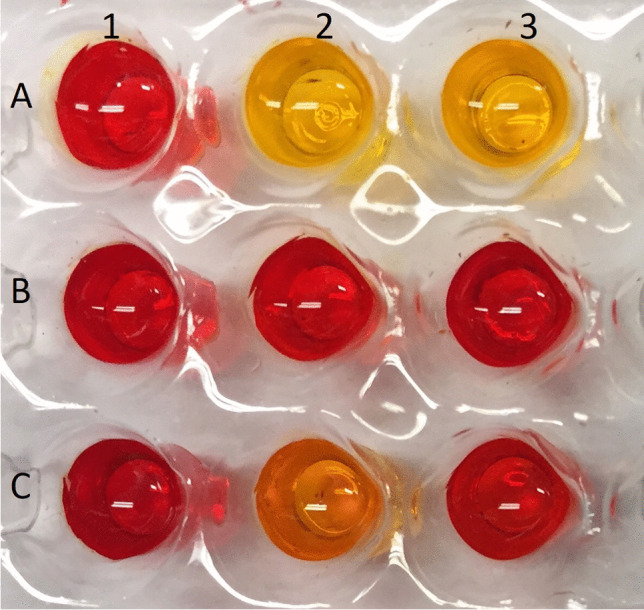

Carba NP was able to correctly identify 52 (92.9%) of the 56 class B-producing isolates, but four blaVIM-2-carrying P. aeruginosa isolates were negative for this test. Among the blaKPC-2-carrying isolates, only one was negative in the Carba NP test. Among carbapenemase-gene negative isolates, 29 out of 32 were correctly identified but three isolates were identified as class B (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Carba NP test. Legend: column: 1, phenol red 0.5% (pH 7.8); 2, phenol red plus 6 mg/ml imipenem; 3, phenol red with 6 mg/ml imipenem and EDTA (10 mM). Line: A, positive control for class A; B, negative control; C, positive control for class B

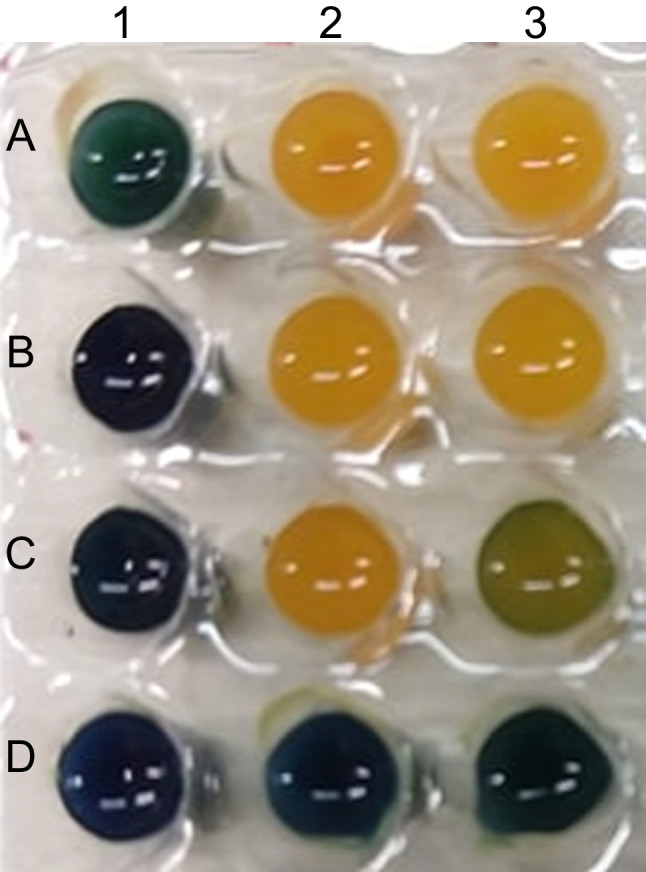

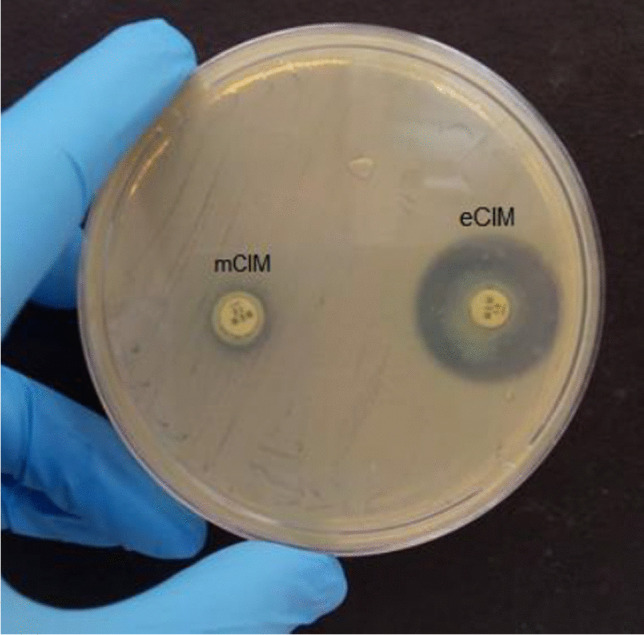

The BlueCarba assay has failed to differentiate the most of class B–producing isolates. Forty-one isolates (73.2%) were identified as class A phenotype and 5 were negative. Only 10 isolates (17.9%) were correctly identified as class B phenotype (NDM-1, n = 1; SPM-1, n = 8; VIM-2, n = 1). Among the blaVIM-2 isolates, 31 out of 35 showed a greenish to yellow color despite the presence of EDTA, giving a false positive class A carbapenemase result, what we call “VIM pattern” (Fig. 2). The same results were found for all EDTA concentrations tested (10 mM, 20 mM, and 40 mM). Among the blaKPC-2-carrying isolates, the BlueCarba was able to correctly identify 35 isolates (89.7%). Three isolates were identified as class B producers and one was considered negative. All carbapenemase-gene negative isolates were negative in this phenotypic test. The mCIM/eCIM tests were able to identify 43 class B–producing isolates (76.8%). Ten were identified as class A producers and three as negative for carbapenemase production. Among blaKPC-2-carrying isolates, 34 (87.2%) were correctly identified, but two isolates showed class B phenotype and three were negative in this test. Among the carbapenemase-gene negative isolates, 31 (96.9%) were negative in this test, while one showed class A phenotype. This same isolate showed class B phenotype in Carba NP and negative in Blue Carba (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Blue Carba test and the VIM pattern. Legend: column: 1, bromothymol blue solution only; 2, bromothymol blue solution plus 6 mg/ml imipenem; 3, bromothymol blue solution with 6 mg/ml imipenem and EDTA (0.1 mM). Line: A, positive control for class A; B, KPC-2 producing P. aeruginosa; C, VIM pattern; D, negative control

Fig. 3.

mCIM/eCIM

We calculated the sensitivity and specificity of each test according to the carbapenemase class (class A or class B). For class B, the observed sensitivity was 92.9%, 17.9%, and 76,8% and specificity of 90.6%, 100%, and 96.8% for Carba NP, BlueCarba, and mCIM/eCIM, respectively. The sensitivity for class A was 97.4%, 89.7%, and 87.2% and the specificity was 96.8%, 100%, and 96.8% for Carba NP, Blue Carba, and mCIM/eCIM, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the genotypic and phenotypic detection of carbapenemases

| Species | Carbapenemase | Carba-NP | BlueCarba | mCIM/eCIM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1uM | 10uM | 20uM | 40uM | ||||

| P. aeruginosa | VIM-2(n = 33) | Class B (29) | Class A (30) | Class A(30) | Class A(30) | Class A(30) | Class A(30) |

| Neg (4) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Neg (3) | ||

| Neg (2) | Neg (2) | Neg (2) | Neg (2) | ||||

| SPM = 1 (n = 17) | Class B (17) | Class B (9) | Class B (9) | Class B (9) | Class B (9) | Class B (14) | |

| Class A (8) | Class A (8) | Class A (8) | Class A (8) | Class A (81 | |||

| Neg (2) | |||||||

| IMP-10 (n = 2) | Class B (2) | Class A (2) | Class A (2) | Class A (2) | Class A (2) | Class B (2) | |

| NDM-1 (N = 1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | |

| VIM-24 (n = 1) | Class B (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Class B (1) | |

| KPC-2 (n = 36) | Class A (35) | Class A (34) | Class A (34) | Class A (34) | Class A (34) | Class A (31) | |

| Neg (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (2) | ||

| Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (1) | Neg (3) | |||

| Carbapenemase | Neg (29) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Neg (30) | |

| Neg (n = 32) | Class A (3) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Neg (32) | Class A (1) | |

| Class B (1) | |||||||

| P. putida | VIM-2 (n = 2) | Class B (2) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (1) | Class B (2) |

| Class A (1) | Class A (1) | Class A (1) | Class A (1) | ||||

| KPC-2 (n = 3) | Class A (3) | Class B (2) | Class B (2) | Class B (2) | Class B (2) | Class A (3) | |

| Class A (1) | Class A (1) | Class A (1) | Class A (1) |

Neg, negative

Discussion

Carbapenems are one of the main choices for the treatment for P. aeruginosa infections and resistance has threatened the use. Non-susceptibility to carbapenems has increased in the world, and in Latin America, the resistance to meropenem reaches 67.7% [14]. Nowadays, the identification of the mechanism behind the resistance becomes fundamental for therapeutic decision and the presence of different carbapenemases has been detected in this species.

In Brazil, in the early 2000s, the presence of class B SPM-1 in P. aeruginosa isolates became a concern with its detection in different geographic regions associated with a single epidemic clone, ST277. In the last years, it is possible to observe the increase and dissemination of class A carbapenemases, such as KPC and class B, like VIM-2, and less frequently the presence of NDM-1 and IMP-like in P. aeruginosa isolates from Brazil [15, 16]. The present study is the first report of VIM-24 and IMP-10 in Brazil. The blaVIM-24 differs from blaVIM-2 by only one nucleotide, G to a T at position 614, leading to A205L in the amino acid chain. This gene has been described in Colombia and there are not many reports on its dissemination [17]. The blaIMP-10 in Brazil has already been detected in Acinetobacter baumannii [18], but this is the first report in P. aeruginosa in Brazil. The blaIMP-10 in P. aeruginosa has been reported in Japan and South Korea [19–21]. Studies have shown that infections caused by class B producers have a mortality rate > 50% [22].

The emergence and increase of different carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa strains need attention. The presence of those carbapenemase-genes in mobile genetic elements contributes to the emergence and dissemination of these enzymes. In this way, this detection is crucial to reduce the mortality and morbidity [4, 23].

In this context, the rapid and reliable detection of carbapenemases can contribute to controlling their dissemination and targeting treatment. The description of new carbapenemase inhibitors (avibactam, relebactam, and vaborbactam) and their association with β-lactams for the treatment of infections caused by carbapenemase-producing bacteria has changed the focus and objective of these methodologies. These discoveries have led to new hope in the treatment of infection caused by multi-drug resistant bacteria, especially for class A producers. Hence, phenotypic tests for detection and differentiation of carbapenemases besides their epidemiological purposes have direct influence in the patient treatment. At the moment, all tests have many limitations for carbapenemase detection, especially for non-fermenters, and have been a challenge to microbiologists [24].

Molecular detection of carbapenemase genes has been considered the golden standard; however, it requires a high cost, time, and qualified professionals. The development of fast, easy, stable, and accurate phenotypic tests for carbapenemase detection has been thought about in recent years [25].

Carba NP, developed in 2012, was the first rapid phenotypic test based on the hydrolysis of carbapenem using phenol red. Since 2015, CLSI has recommended this test for Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa (CLSI 2015). The use of this test includes runtime, with sensitivity and specificity > 90% in most cases of Enterobacterales and P. aeruginosa. Limitations include inoculum size, pH accuracy, use of commercial reagents, and recent microbial growth. The use of in-house buffers and imipenem/cilastatin, most commonly found in hospitals, has improved testing costs [26–29]. In this study, Carba NP test showed sensitivity and specificity > 90% for the detection of class A and class B carbapenemase, using commercial buffer for protein extraction, but other in-house solutions and imipenem/cilastatin with good performance and interpretation [30].

The Blue Carba test is also based on the hydrolysis of carbapenem but using bromothymol blue and can be performed directly from the bacterial isolates. The color change is easier to view (blue/greenish) compared to Carba NP (yellow/orange). Previous studies have shown good sensitivity and specificity for carbapenemase detection, mainly in Enterobacterales [31]. In P. aeruginosa, Simner and collaborators [32] found 100% of sensitivity and 77% of specificity in carbapenemase detection (n = 14), including KPC, VIM, IMP, and SPM producing, despite of the number of isolates analyzed is very small. Cunha and collaborators found 100% sensitivity and specificity for SPM-1 (n = 23) [7]. However, these studies did not consider the differentiation between class A and class B. In our study, regardless of the type of carbapenemase, class A or class B, the sensitivity was 93.6%, but when class B was differentiated by addition of EDTA, the sensitivity drops dramatically to 17.9%. Sensitivity remained low even after increasing EDTA concentration showing a limitation of this test.

The mCIM has been recommended for the detection of carbapenemase in P. aeruginosa according to CLSI and the variant eCIM using EDTA to differentiate between class A and class B for Enterobacterales (CLSI 2018). In the present study, these tests associated showed sensitivity > 85% for class B and class A for Pseudomonas spp. isolates. Gill and collaborators [33] observed sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 85% for mCIM and high correlation in differentiating between classes A and B. Our study was able to detect 12 of the 17 SPM-1 and the 2 IMP-10-producing isolates by eCIM.

Comparing cost–benefit of each test, we see that in relation to the turnaround time of tests, the Blue Carba is the fastest, since Carba NP needs an initial extraction step and the mCIM/eCIM takes 18–24 h for results to be read. The mCIM/eCIM proved to be the easiest to perform, since it uses media and reagents common to the microbiology laboratory, while Carba NP and Blue Carba need measurement by weight of imipenem powder, adjusting the pH of solutions, and cautious pipetting, in addition to the purchase of extraction buffer for Carba NP.

The use of class B inhibitors has been increasingly important and necessary in phenotypic tests. In our study, we had trouble distinguishing class B using EDTA as inhibitor in Blue Carba test. These carbapenemases have zinc in their active site and their action is inhibited by metal chelators that sequester ions from the medium. Some inhibitors can only be used in vitro because they are toxic to the human body, as is the case of EDTA. EDTA has been reported to have antimicrobial activity against some bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa. Its mechanism of action involves the sequestration of ions from the outer membrane, such as Mg2 + and Ca2 + , leading to its destabilization and permeabilization. In addition, it can potentiate other antimicrobials, decreases the virulence of P. aeruginosa by inhibiting metalloproteases, such as alkaline proteases and elastase, and has action against biofilm [34, 35]. In this way, the very low sensitivity of Blue Carba, using EDTA (17.9%), possibly may be due to the antimicrobial activity of EDTA, releasing components from the periplasmic space and acidifying the medium, leading to a false negative for class A carbapenemases. In the mCIM/eCim test, this is not noticeable because a pH indicator is not used, while in CarbaNP the bacteria are lysed before and the pH of the test is higher than that of BlueCarba, making the pH variation imperceptible. Thus, further evaluation of other class B inhibitors is necessary for improving the carbapenemase detection in Pseudomonas spp. Our study shows many limitations of the tests, where the Blue Carba assay had the worst performance for carbapenemase differentiation using EDTA.

Acknowledgements

We thank the PDTIS-IOC DNA Sequencing Platform for DNA sequencing.

Funding

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação Carlos Chagas de Amparo à Pesquisa (FAPERJ), and Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (IOC)—Fiocruz.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, Pulcini C, Kahlmeter G, Kluytmans J, Carmeli Y, Ouellette M, Outterson K, Patel J, Cavaleri M, Cox EM, Houchens CR, Grayson ML, Hansen P, Singh N, Theuretzbacher U, Magrini N, WHO (2018) Pathogens Priority List Working Group. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 18(3):318–327. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Horcajada JP, Montero M, Oliver A, Sorlí L, Luque S, Gómez-Zorrilla S, Benito N, Grau S (2019) Epidemiology and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 32(4):e00031–19. 10.1128/CMR.00031-19. Print 2019 Sep 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Tamma PD, Simner PJ (2018) Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms from clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol 56(11):e01140–18. 10.1128/JCM.01140-18. Print 2018 Nov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.de Oliveira Santos IC, de Andrade NFP, da Conceição Neto OC, da Costa BS, de Andrade Marques E, Rocha-de-Souza CM, Asensi MD, D’Alincourt Carvalho-Assef AP (2019) Epidemiology and antibiotic resistance trends in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Rio de Janeiro - Brazil: importance of mutational mechanisms over the years (1995–2015). Infect Genet Evol 73:411–415. 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Aurilio C, Sansone P, Barbarisi M, Pota V, Giaccari LG, Coppolino F, Barbarisi A, Passavanti MB, Pace MC. Mechanisms of action of carbapenem resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11(3):421. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botelho J, Grosso F, Peixe L. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa - mechanisms, epidemiology and evolution. Drug Resist Updat. 2019;44:100640. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Cunha RSR, Carniel E, Narvaez GA, Dias CG, Perez LRR (2020) Impact of the blue-carba rapid test for carbapenemase detection on turnaround time for an early therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Infect Control S0196–6553(20)30802–6.10.1016/j.ajic.2020.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bialvaei AZ, Kafil HS, Asgharzadeh M, Yousef Memar M, Yousefi M. Current methods for the identification of carbapenemases. J Chemother. 2016;28(1):1–19. doi: 10.1179/1973947815Y.0000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Silva IR, Aires CAM, Conceição-Neto OC, de Oliveira Santos IC, Ferreira Pereira N, Moreno Senna JP, Carvalho-Assef APD, Asensi MD, Rocha-de-Souza CM. Distribution of clinical NDM-1-producing gram-negative bacteria in Brazil. Microb Drug Resist. 2019;25(3):394–399. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franco MRG, Caiaffa‐Filho HH, Burattini MN, Rossi F (2010) Metallo‐beta‐lactamases among imipenem‐resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Brazilian university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 65(9):825–829 10.1590/S1807-59322010000900002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3773–3776. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pires J, Novais Â, Peixe L. Blue-Carba, an easy biochemical test for detection of diverse carbapenemase producers directly from bacterial cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(12):4281–4283. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01634-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalkhen AG, McCluskey A. Clinical tests: sensitivity and specificity. Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8(6):221–223. doi: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkn041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shortridge D, Gales AC, Streit JM, Huband MD, Tsakris A, Jones RN (2019) Geographic and temporal patterns of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over 20 years from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997–2016. 6(Suppl1):S63-S68. 10.1093/ofid/ofy343 eCollection 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Gales AC, Menezes LC, Silbert S, Sader HS. Dissemination in distinct Brazilian regions of an epidemic carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing SPM metallo-beta lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(4):699–702. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizek C, Fu L, Dos Santos LC, Leite G, Ramos J, Rossi F, Guimaraes T, Levin AS, Costa SF. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates, carrying multiple genes coding for this antibiotic resistance. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;2(13):43. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0043-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montealegre MC, Correa A, Briceño DF, Rosas NC, De La Cadena E, Ruiz SJ, Mojica MF, Camargo RD, Zuluaga I, Marin A, Quinn JP, Villegas MV, Colombian Nosocomial Resistance Study Group (2011) Novel VIM metallo-beta-lactamase variant, VIM-24, from a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Colombia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55(5):2428–30. 10.1128/AAC.01208-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Cayô R, Rodrigues-Costa F, Matos AP, Carvalhaes CG, Jové T, Gales AC. Identification of a new integron harboring blaIMP-10 incarbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(6):3687–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04991-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyobe S, Kusadokoro H, Takahashi A, Yomoda S, Okubo T, Nakamura A, O’Hara K. Detection of a variant metallo-beta-lactamase, IMP-10, from two unrelated strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an alcaligenes xylosoxidans strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(6):2014–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.2014-2016.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao WH, Chen G, Ito R, Hu ZQ. Relevance of resistance levels to carbapenems and integron-borne blaIMP-1, blaIMP-7, blaIMP-10 and blaVIM-2 in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 8):1080–1085. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.010017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong JS, Yoon E-J, Lee H, Jeong SH, Lee K (2016) Clonal dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence type 235 isolates carrying blaIMP-6 and emergence of blaGES-24 and blaIMP-10 on novel genomic islands PAGI-15 and -16 in South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60(12):7216–7223. 10.1128/AAC.01601-16. Print 2016 Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zavascki AP, Goldani LZ, Gonçalves AL, Martins AF, Barth AL. High prevalence of metallo-beta lactamase-mediated resistance challenging antimicrobial therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Epidemiol Infect. 2007;135(2):343–345. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A, Tran TT, Rios R, Hanson B, Shropshire WC, Sun Z, Diaz L, Dinh AQ, Wanger A, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Palzkill T, Arias CA, Miller WR (2019) Extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST309 harboring tandem guiana extended spectrum β-lactamase enzymes: a newly emerging threat in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis 6(7):ofz273. 10.1093/ofid/ofz273. eCollection 2019 Jul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Vázquez-Ucha JC, Arca-Suárez J, Bou G, Beceiro A. New carbapenemase inhibitors: clearing the way for the β-lactams. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):9308. doi: 10.3390/ijms21239308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguirre-Quiñonero A, Martínez-Martínez L. Non-molecular detection of carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Rapid identification of carbapenemase types in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. by using a biochemicaltest. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(12):6437–40. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01395-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Literacka E, Herda M, Baraniak A, Zabicka D, Hryniewicz W, Skoczynska A, et al. (2017) Evaluation of the Carba NP test for carbapenemase detection in Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp., and its practical use in the routine work of a national reference laboratory for susceptibility testing. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36(11):2281–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dortet L, Brechard L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Impact of the isolation medium for detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae using an updated version of the Carba NP test. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63(Pt 5):772–776. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.071340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouslah Z. Carba NP test for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50(6):466–479. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterblad M, Hakanen AJ, Jalava J. Evaluation of the carba NP test for carbapenemase detection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7553–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02761-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pancotto LR, Nodari CS, Rozales FP, Soldi T, Siqueira CG, Freitas AL, Barth AL. Performance of rapid tests for carbapenemase detection among Brazilian Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Braz J Microbiol Oct-Dec. 2018;49(4):914–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simner PJ, Opene BNA, Chambers KK, Naumann ME, Carroll KC, Tamma PD. Carbapenemase detection among carbapenem-resistant glucose-nonfermenting gram-negative Bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(9):2858–2864. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00775-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill CM, Lasko MJ, Asempa TE, Nicolau DP. Evaluation of the EDTA modified carbapenem inactivation method for detecting metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(6):e02015–19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02015-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lambert RJ, Hanlon GW, Denyer SP. The synergistic effect of EDTA/antimicrobial combinations on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:244–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2004.02135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaara M. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:395–411. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.395-411.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lasko MJ, Gill CM, Asempa TE, Nicolau DP. EDTA-modified carbapenem inactivation method (eCIM) for detecting IMP metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an assessment of increasing EDTA concentrations. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01902-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]