Abstract

In order to study the change laws of free radicals and functional groups during low-temperature coal oxidation, three coal samples with different metamorphic degrees were selected for ESR and FTIR analysis. The results showed that the concentration of free radicals increased as the temperature increased; meanwhile, the types of free radicals changed constantly, and the free radical variation range decreased with the increase in coal metamorphism. The side chains of aliphatic hydrocarbons in coal with a low metamorphic degree decreased by varying amounts in the initial heating stage. The −OH content of bituminous coal and lignite increased first and then decreased, while that in anthracite decreased first and then increased. In the initial oxidation stage, −COOH first increased rapidly, then decreased rapidly, and then increased before finally decreasing. The content of −C=O in bituminous coal and lignite increased in the initial stage of oxidation. Through gray relational analysis, it was found that there was a significant relationship between free radicals and functional groups, and −OH had the strongest correlation with free radicals. This paper provides a theoretical basis for studying the mechanism of functional groups transforming into free radicals in the process of coal spontaneous combustion.

1. Introduction

There are rich coal resources in China, which is one of the world’s major coal-producing countries. In China, coal spontaneous combustion (CSC) poses a constant threat to the safe production of mines.1 The risk of spontaneous combustion exists in 51.3% of the state-owned key coal mines.2 CSC events not only destroy a large amount of coal resources but also release toxic and harmful gases, which threaten the atmospheric environment and the lives and safety of underground personnel and even lead to gas and coal dust explosion accidents.3−6 CSC occurs as a result of heat accumulation because of the reaction of active microstructures in coal with oxygen.7 Adsorption heat is generated when coal adsorbs oxygen; this leads to the oxidation of the active structure, which then releases a significant amount of heat and finally leads to the spontaneous combustion of coal.8 This process involves complex physical and chemical changes, including free radical reactions and the oxidation of functional groups.9,10 Many scholars have used advanced technologies, such as electron spin resonance (ESR) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), to study the free radicals and functional groups in the coal–oxygen reaction.

Qiu et al.11 analyzed the changes in the concentration of free radicals through a coal pyrolysis experiment; they found that the free radical concentration increased as the time and temperature increased and established the relationship between the temperature–time index and free radical concentration. Liu et al.12−14 studied the free radical characteristics of ultrafine pulverized coal and found that the free radical concentration increased with an increase in coal metamorphism and a decrease in particle size. Zhou et al.15 used ESR to study the effect of oxygen concentration on free radicals in the low-temperature coal oxidation process. It was found that, with the increase in the oxygen concentration, the free radical concentration, line width, and other parameters gradually increased. When the oxygen concentration was lower than 9%, the free radical reaction rate was lower. Hu et al.16 analyzed the influence of different concentrations of methane on free radicals in the coal–oxygen reaction; they found that, with an increased methane concentration, the concentration of free radicals decreased and the g-factor gradually increased. Zhou et al.17 studied the influence of particle size on coal spontaneous combustion and found that, with an increase in temperature and a decrease in the coal particle size, the concentration of free radicals and the g-value increased continuously and the line width decreased. The main temperature range for the increase in the concentration of free radicals was 150–250 °C. Jiang et al.18 tested the changes of free radical parameters when coal was oxidized in different gas environments and analyzed the mechanism of the influence of gas on free radicals.

Zhang et al.19 studied the oxidation characteristics of functional groups in three coal samples using FTIR. It was found that, as the coal metamorphism increased, the content of aliphatic hydrocarbons and aromatic hydrocarbons gradually increased while the content of oxygen-containing groups decreased. −OH was the most active functional group in the oxidation process. Liu et al.20 studied the effect of oxygen concentrations on functional groups during low-temperature oxidation and determined that functional groups of −OH, aliphatic hydrocarbons, aromatic hydrocarbons, and −COOH are of great importance in the process of coal spontaneous combustion. Qi et al.21 used a self-designed FTIR system to test real-time changes in the functional groups of coal in an anaerobic reaction and described the process whereby gaseous products are generated under anaerobic conditions. Qin et al.22 studied the changes in the organic functional groups of coal after freezing with liquid nitrogen and found that the proportion of oxygen-containing functional groups increased as the freezing time increased, while the proportion of aliphatic hydrocarbons and substituted benzene decreased. Niu et al.23 used FTIR technology to study the changes in functional groups during the pyrolysis of different coal samples. The results showed that the aliphatic group tended to be stable as the coal metamorphism increased, and the decomposition activation energy of aliphatic group and −OH at the high-temperature stage was significantly higher than that at the low-temperature stage. Xi et al.24 studied the effect of adsorbed water on low-temperature coal oxidation and found that the reactivity of functional groups and adsorbed water was low and that the adsorbed water can promote the reaction of aliphatic and carbon free radicals with oxygen. Li et al.25 studied the combustion behavior of pulverized coal and found that the type and yield of volatile matter of coal were obviously related to the type and quantity of functional groups.

Zhou et al.26 used ESR and FTIR to study the way in which different oxygen concentrations influence free radicals and functional groups during the low-temperature oxidation of goaf coal. It was found that the concentration of free radicals increased with the increase in the oxygen concentration. When the oxygen concentration exceeded 9%, the concentration of free radicals increased, and the functional groups were more prone to react. Xu et al.27 analyzed the influence of different CH4 concentrations on free radicals and functional groups in the process of low-temperature coal oxidation and determined the main functional group that reacts. With an increased CH4 concentration, the concentration of free radicals decreased; the existence of CH4 has a certain inhibitory effect on the reaction of −CH2, −CH3, −OH, and −COOH and has a promoting effect on the formation of −C–O. Xu et al.28 studied the reaction characteristics of free radicals and functional groups during the low-temperature oxidation of coals with different metamorphic degrees. After reaching a certain temperature, the concentration of free radicals increased rapidly, and the change trends of functional groups were quite different in different coals. Xu et al.29 measured the changes in free radicals and functional groups during the primary and secondary oxidation of three coal samples and found that primary oxidation could improve the oxidation activity of fatty hydrocarbons, thus promoting secondary oxidation. With the rise in the secondary oxidation temperature, the concentration of free radicals tended to decline. Wang et al.30 studied the low-temperature oxidation process of coal after drying by nitrogen and found that, during the drying process, −OH and carbonyl compounds decomposed, generating free radical active sites on the coal’s surface. The subsequent oxidation of the accumulated free radicals not only released a large number of carbon oxides but also promoted the formation of oxygen-containing groups. Wei31 studied the change laws of free radicals and functional groups in the process of low-temperature oxidation and explained the reaction process of free radicals according to the three stages of chain initiation, chain transfer, and chain termination, based on the chain reaction theory.

Gray relational analysis can determine the relationship between variables in complex systems. It is not limited by the quantity of samples or by data regularity and has been widely used in the energy field.32,33 Zhang et al.34 studied the relationship between functional groups and thermal effects in the CSC process and found that the correlation between functional groups and thermal effects in different reaction stages showed similar laws. Zhu et al.35 carried out gray relational analysis on functional groups and the gas concentrations produced in the different oxidation stages of minerals, and determined the key structure that influences the spontaneous combustion of minerals. Using gray relational calculations, Zhao et al.36 determined that −C=O is the key functional group that promotes CH4 in the CSC process. Also using gray relational analysis, Wang et al.37 studied the relationship between activation energy, free radicals, and functional groups in the low-temperature oxidation process of Jurassic coal, and found that methyl, methylene, carboxyl, and aromatic double bonds had a relatively large impact on the free radicals of the studied coal samples. In the coal–oxygen reaction, free radicals are closely related to functional groups, and functional groups are important substances that affect the chain reaction activity of coal–oxygen free radicals.

In this study, we selected three coal samples with different metamorphic degrees: lignite, bituminous coal, and anthracite. ESR and FTIR spectroscopy were used to obtain the ESR and FTIR spectrograms of coal samples at 20, 50, 70, 90, 110, 130, and 150 °C. The free radical concentration, g-factor, line width, and main functional group content of the three coal samples at the corresponding oxidation temperatures were obtained through data processing, and the change characteristics of free radicals and functional groups in the oxidation process of the three coal samples were analyzed. Using gray relational analysis, the correlation between free radicals and functional groups in the low-temperature oxidation process of the three kinds of coal samples was calculated to explore the relationship between them. This paper provides a theoretical basis for fully understanding the process of coal spontaneous combustion and studying effective fire prevention and extinguishing methods.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Coal Sample Preparation

Three kinds of coal samples (Figure 1) were selected for the experiment. The coal samples were anthracite, bituminous coal, and lignite, classified by the metamorphic degree from high to low. The selected coal samples were anthracite from the fifth mine of Pingding County, Yangquan City, Shanxi Province, bituminous coal from working face 13817 of the south third mining area of Yueliangtian Mine in Panjiang, Guizhou Provinve, and lignite from the Baorixile mine. These coal samples were crushed and screened to obtain 80–120 mesh pulverized coal (Figure 2). Then they were dried and reserved for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Three different types of coal.

Figure 2.

Pulverized coal after crushing and screening.

2.2. Experiment

(1) The pulverized coal of each coal sample was divided into 7 parts, and one part was sealed and placed at 20 °C. The other 6 parts were put into the oven in turn, oxidized at 50, 70, 90, 110, 130 and 150 °C for 8 h respectively, and then sealed in vacuum bags. These pulverized coal sample would be used for subsequent ESR and FTIR experiments.

(2) A JES-FA200 ESR spectrometer manufactured by Japanese electronics JE0L was used for the free radical test in this experiment. A quartz thin-walled tube with an outer diameter of 2 mm was used to penetrate into the pulverized coal to obtain the powder column. An analytical balance with an accuracy of 0.1 mg was used to weigh precisely 2.0 mg, and the quartz thin-walled tube containing the coal sample was then placed into a resonant cavity for the experimental test. The operating conditions were as follows: a scanning time of 1 min, a central magnetic field of 323.386 mT, a scanning width of 5 × 1 mT, a modulation frequency of 100.00 kHz, a modulation width of 1.0 × 0.1 mT, a microwave frequency of 9052.673 MHz, a time constant of 0.03 s.

(3) A V70/HYPERION 1000 FTIR manufactured by Bruker, USA was used for the functional group test. An appropriate amount of the sample to be tested was placed on a white steel table in the FTIR attachment. The sample was evacuated and paved evenly on the table, and then the device sensor head was pressed onto the paved sample for test. The resolution was 4 cm–1, the sample scanning time and background scanning time were 2 min, and the experimental wavenumber range was 600–4000 cm–1.

2.3. Gray Relational Analysis

Gray relational analysis is a method used to determine the primary and secondary factors that lead to a system change by calculating the relational degree between a reference sequence and a comparison sequence. Unlike traditional methods of analysis, gray relational analysis is not limited by the sample quantity or data regularity and is widely used in many fields.

The analytical steps are as follows:

-

(1)Determine the reference sequence X0 and the comparison sequence Xi.

1

2 -

(2)Nondimensionalize the date. The average method was adopted in this paper.

3 -

(3)Determine the deviation sequence Δ0i(k), maximum values M, and minimum values m:

4

5

6 -

(4)Determine the gray relational coefficient Pi:

where ρ is the resolution coefficient, 0< ρ< 1. Generally, ρ is taken as 0.5.

7 -

(5)Determine the gray relational grade Ri:

8

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Free Radicals

Table 1 shows the main parameters obtained through the ESR spectrum.

Table 1. Main Parameters of the ESR Spectra of Various Coal Samples at Different Oxidation Temperatures.

| Type | Temperature (°C) | G-factor | Linewidth ΔH (mT) | Free radical concentration Ng (1018 g–1) | Free radical increment (1018 g–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracite | 20 | 2.00310 | 565 | 11.97 | |

| 50 | 2.00317 | 587 | 12.07 | 0.1 | |

| 70 | 2.00312 | 573 | 13.06 | 0.99 | |

| 90 | 2.00314 | 580 | 14.17 | 1.11 | |

| 110 | 2.00312 | 580 | 13.82 | –0.35 | |

| 130 | 2.00317 | 594 | 14.24 | 0.42 | |

| 150 | 2.00314 | 588 | 14.90 | 0.66 | |

| Bituminous coal | 20 | 2.00292 | 434 | 11.832 | |

| 50 | 2.00283 | 360 | 12.0 | 0.168 | |

| 70 | 2.00292 | 316 | 12.743 | 0.743 | |

| 90 | 2.00290 | 294 | 13.029 | 0.286 | |

| 110 | 2.00290 | 264 | 12.742 | –0.287 | |

| 130 | 2.00289 | 257 | 13.448 | 0.706 | |

| 150 | 2.00292 | 242 | 15.793 | 2.345 | |

| Lignite | 20 | 2.00332 | 646 | 9.114 | |

| 50 | 2.00343 | 683 | 8.139 | –0.975 | |

| 70 | 2.00336 | 683 | 9.280 | 1.141 | |

| 90 | 2.00350 | 705 | 7.749 | –1.531 | |

| 110 | 2.00341 | 668 | 16.27 | 8.521 | |

| 130 | 2.00346 | 675 | 14.88 | –1.39 | |

| 150 | 2.00341 | 653 | 19.39 | 4.51 |

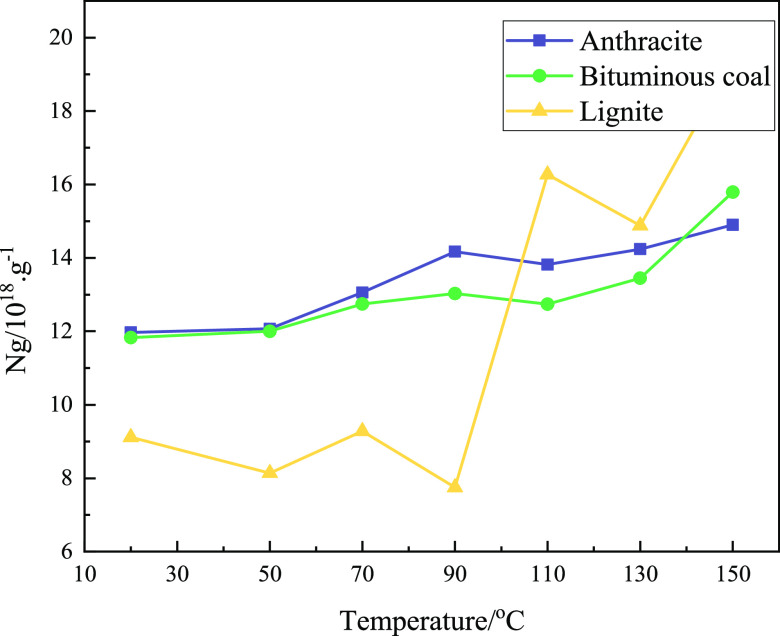

3.1.1. Free Radical Concentration Ng

The free radical concentration Ng represents all the free radicals in the sample. The higher the concentration, the more radicals are present in the sample. Figure 3 shows the free radical concentration curves of different coal samples and the radical concentration curves of the same coal samples under different oxidation temperatures. It can be seen that, during the oxidation process, the free radical concentration of the three coal samples showed an overall increasing trend, and the change range was small at the initial stage of oxidation. In the initial coal samples, the free radical contents of anthracite were slightly higher than those of bituminous coal, while the free radical contents in lignite were significantly lower than those in anthracite and bituminous coal. When the oxidation temperature increased to 90 °C, the concentration of free radicals in lignite increased rapidly and then exceeded that of anthracite and bituminous coal with a higher metamorphic degree. In the process of coal metamorphism, the increase in alkane fragments led to an increase in free electrons; thus, the concentration of free radicals increased. When it came to the anthracite stage, the concentration of free electrons was too large; this made it easier for them to pair with each other, thus leading to a decrease in the concentration of free radicals. Therefore, the concentration of free radicals in anthracite and bituminous coal was almost the same as at the initial temperature. It is suggested that the change in the concentrations of free radicals for each coal sample is related to the degree of coal metamorphism and the oxidation temperature. The concentration of free radicals increased with the increase in the oxidation temperature. The higher the degree of coal metamorphism, the higher the concentration of free radicals. It can be seen from the figure that there was a certain fluctuation in the process whereby the free radical concentration increased and that the concentration of free radicals in lignite increased sharply after 90 °C. This means that the change in the concentration of free radicals in the process of low-temperature coal oxidation was probably the result of the comprehensive action of many factors; the reaction may be complex.

Figure 3.

Free radical concentration (Ng) changes with the oxidation temperature.

3.1.2. g-Factor

The g-factor in the ESR spectrum represents the type of free radicals present in the sample. If the g-factor changes, it indicates that the type of free radicals in the sample has changed. Figure 4 shows the g-factors of different coals and the g-factor curves of the same coal at different oxidation temperatures. It can be seen that the g-factor values of the three coal samples exhibited a range of changes during the low-temperature oxidation process. The g-factor of lignite fluctuated continuously during oxidation, with the largest changes. The g-factor of bituminous coal decreased at 20–70 °C, then rose, and then tended to be flat. The g-factor of anthracite showed the smallest change range.

Figure 4.

G-factor changes with the oxidation temperature.

3.1.3. Line Width ΔH

Line width refers to the width between the peaks of the first differential curve. It can reflect the change of the symmetry of free radicals. Therefore, the change of free radical species can be obtained from the line width. The smaller the line width or the greater the change of the line width, the greater the change of the free radical species. Figure 5 shows the line widths of different coals and the line width curves of the same coal at different oxidation temperatures. The curves show that, with the increase in temperature, the line width of bituminous coal narrowed rapidly, showing an overall narrowing trend. The line width of anthracite tended to widen with the increase in temperature, but the speed of this widening was relatively slow. The line width of lignite widened with the increase in the oxidation temperature between 20–90 °C and then narrowed with the increase in the oxidation temperature between 90–150 °C. The curve change trends of the two temperature sections were basically symmetrical with respect to 90 °C. With the increase of temperature, the line width of bituminous coal decreased, and the change range was the largest. It indicated that the species of free radicals changed greatly in bituminous coal. The line width of anthracite and lignite had always been larger than that of bituminous coal, and the change is relatively gentle. It indicated that the change of free radical species was small in anthracite and lignite.

Figure 5.

Line width changes with the oxidation temperature.

3.2. Analysis of the Experimental Results of the Functional Group Determination

Quantitative analysis of the obtained FTIR spectrogram was conducted according to Beer’s law. Based on this law, the content of each main active functional group in coal was quantitatively analyzed using the characteristic peak area. According to the functional group attribution table, the main types of active functional groups in coal were identified, the fitting area of each characteristic peak was obtained according to the fitting results, and the proportion of each active functional group was obtained.

3.2.1. Change Laws of the Content of the Aliphatic Hydrocarbon Side Chain with Changes in the Oxidation Temperature

The aliphatic hydrocarbon side chains discussed in this paper mainly include the methyl antisymmetric stretching vibration, the methylene antisymmetric stretching vibration, and methylene. It can be seen from Figure 6 that, at the initial stage of oxidation, the aliphatic hydrocarbon side chain of anthracite increased slightly and then decreased rapidly as the temperature increased. That of bituminous coal at 20–50 °C showed basically no change and then decreased rapidly at 50–90 °C. At the initial stage of oxidation, the aliphatic hydrocarbon side chain of lignite decreased rapidly and then increased sharply with the increase in the temperature. At the initial stage of oxidation, the content of aliphatic hydrocarbon side chains in lignite decreased, while that in bituminous coal was basically unchanged and that in anthracite increased; this indicates that aliphatic hydrocarbons in coal samples with a low metamorphic degree mostly exist as long chains. Long chains have high activity and are easily oxidized, so the aliphatic hydrocarbon side chains of coal with a low degree of metamorphism would be reduced to varying degrees at the initial stage of heating. Then, with the continuous increase in the oxidation temperature, the long chain of aliphatic hydrocarbons broke into small chains; moreover, because of the collision between the broken side chains and other chains or free radicals, more −CH, −CH3, and −CH2– were formed. The whole process constitutes the continuous production and consumption of −CH, −CH3, and −CH2–, resulting in the alternating rise and fall of its overall content.

Figure 6.

Changes in aliphatic hydrocarbon side chain content with the oxidation temperature.

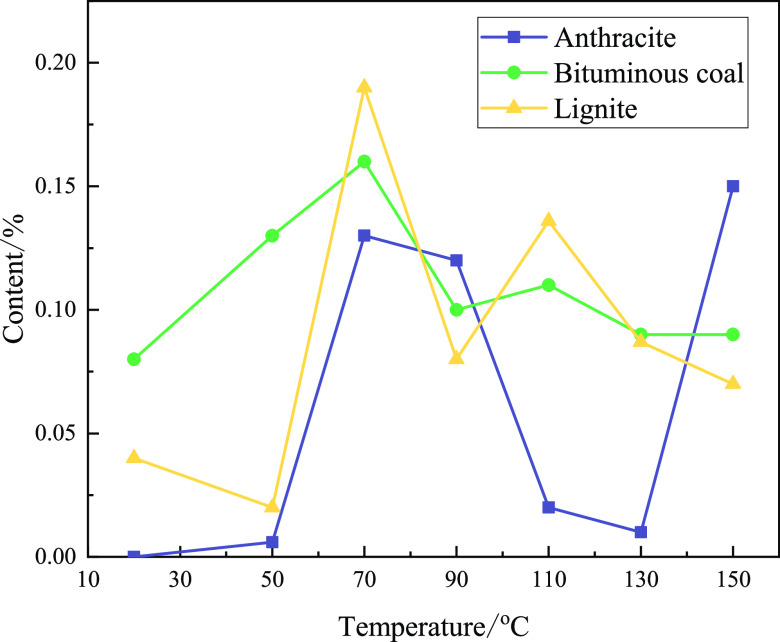

3.2.2. Change Laws of the Content of Oxidation-Containing Functional Groups with the Oxidation Temperature

3.2.2.1. Changes in the Hydroxyl (−OH) Content with the Oxidation Temperature

It can be seen from Figure 7 that at the initial stage of oxidation the content of −OH in lignite increased first. Then the content of −OH decreased between 50 and 90 °C and rose again after the temperature exceeded 90 °C. The change of the content of −OH in bituminous coal was relatively gentle. The content of −OH rised before 90 °C and decreased after 90 °C. In anthracite, meanwhile, the content of −OH first decreased, then increased, and then decreased. At the initial stage of oxidation, the higher the coal’s metamorphic degree, the greater the reduction in the −OH content. The reason for the significant increase in the −OH content in bituminous coal and lignite at the initial stage of oxidation is that the initial concentration of −OH in bituminous coal and lignite is lower. It can clearly be seen from Figure 6 that the content of aliphatic hydrocarbons in bituminous coal and lignite decreased at the initial stage of oxidation, while the content of −OH increased significantly, indicating that the aliphatic hydrocarbons were largely involved in the oxidation reaction to generate −OH. Then, with the increase in the oxidation temperature or the action of the chemical bond, −OH further oxidized, undergoing a continuous generation and consumption process. Anthracite had the highest degree of metamorphism, and the −OH content in the initial coal sample was already very high. When the oxidation temperature rose, a large amount of −OH was oxidated to generate other groups, so its content was greatly reduced.

Figure 7.

Changes in −OH content with the oxidation temperature.

3.2.2.2. Change in Carboxyl (−COOH) Content with the Oxidation Temperature

It can be seen from Figure 8 that the change trend for −COOH in the three coal samples was generally consistent; first, it increased rapidly and then rapidly declined at the initial oxidation stage. −COOH is an important group in the coal oxidation process. It is produced by the oxidation of −OH or −C=O and decomposes easily during high-temperature oxidation. Therefore, −COOH in coal generally exists in a transitional state. At the initial stage, the content of −COOH in the three coal samples was very low. After low-temperature oxidation, a large amount of −OH and −C=O reacted with oxygen to generate −COOH at 20–70 °C, and the content of −COOH increased significantly. With the continuous increase in the oxidation temperature, −COOH began to decompose, and the decomposition rate is greater than the rate of generation; as such, the content of −COOH decreased. Comparing the three curves, it can be seen that the inflection point of the sharp decline in −COOH levels was 70 °C, indicating that the decarboxylation reaction of −COOH in the three coals occurred rapidly at this time.

Figure 8.

Changes in the −COOH content with the oxidation temperature.

3.2.2.3. Changes in Carbonyl Group (−C=O) Content with the Oxidation Temperature

–C=O is a highly important functional group in the coal oxidation heating stage; it is generally produced by the oxidation of the side chain of aliphatic hydrocarbons and −OH. −C=O is also a highly active oxygen-containing functional group and can be further oxidated to generate −COOH. −C=O in aldehydes and ketones is the primary subject of this paper. According to Figure 9, and in results consistent with −COOH, the content of −C=O was very low at the initial stage. At the initial oxidation stage of anthracite, the content of −C=O decreased because of the low content of aliphatic hydrocarbons; as such, the rate at which it was oxidated to −C=O was slow at the initial temperature, while the existing −C=O was oxidated to other groups. The −C=O content in bituminous coal and lignite increased at the initial stage of oxidation, and the −C=O growth rate of lignite was the fastest, which further indicates that the −C=O was mainly produced by the oxidation of the aliphatic hydrocarbon side chain.

Figure 9.

Changes in the −C=O content with the oxidation temperature.

3.2.2.4. Changes in the Content of the Phenol, Alcohol, Ether, and Ester Oxygen Bond (−Ar–C–O) with the Oxidation Temperature

–Ar–C–O is also mainly generated from the side chain of aliphatic hydrocarbons. It is highly active and easily oxidated to other groups. It can be seen from Figure 10 that the content of −Ar–C–O of anthracite and bituminous coal decreased at the initial stage of oxidation. This is because the content of aliphatic hydrocarbons in anthracite and bituminous coal was relatively low, and the production of −Ar–C–O was less than the consumption. The aliphatic hydrocarbon content of lignite was relatively high. At the initial stage of oxidation, more aliphatic hydrocarbon side chains participated in the reaction to generate −Ar–C–O; the production amount was greater than the consumption amount, so its content increased. The later fluctuation mainly depended on the relationship between the production and consumption of −Ar–C–O.

Figure 10.

Changes in the −Ar–C–O content with the oxidation temperature.

3.3. Relationship between Free Radicals and Functional Groups

Gray relational analysis was used to determine the relationship between the concentration of free radicals and the content of the above functional groups in the process of low-temperature coal oxidation. The free radical concentrations of the three coal samples were taken as the reference sequences, and the content of each functional group was taken as the comparison sequence. The analysis results are shown in Figure 11. The larger the relational grade value, the stronger the correlation. When the relational grade is greater than 0.6, the degree of correlation is considered to be significant. Since the coal structure was complex and diverse, and the low-temperature oxidation process involved complex reactions between functional groups and free radicals, the correlation degree differed between different functional groups and free radicals. From the results of the relational analysis, it can be seen that only −C=O in bituminous coal and anthracite had a relational grade with free radicals of slightly less than 0.6, which indicates that the functional groups explored in this paper have a significant degree of correlation with free radicals during low-temperature oxidation. In anthracite and bituminous coal, there were obvious differences in the correlation degrees between free radicals and different functional groups; meanwhile, in lignite, the difference was very small. In the three kinds of coal sample, the relational grade between −OH and free radicals was the largest, which shows that −OH is closely related to free radicals in the low-temperature coal oxidation reaction. On the one hand, −OH is an important functional group in the process of coal oxidation. It has poor stability and reacts easily. −OH had the highest content and a large range of change in the three kinds of coal, indicating that it is widely involved in a variety of reactions in the process of coal oxidation; these reactions may affect the production and consumption of free radicals. On the other hand, according to the chain reaction theory, the most active stage was the chain transfer stage, where peroxides played an important role. Peroxides could be formed in the −OH oxidation process.

Figure 11.

Relational grade between free radical concentration and functional groups in the three coal samples.

4. Conclusions

In this study, ESR and FTIR were used to study the change laws of free radicals and functional groups during the low-temperature oxidation of anthracite, bituminous coal, and lignite. The relational grade between free radicals and functional groups was obtained using gray relational analysis, and the functional group with the greatest correlation with free radicals was determined. The conclusions are as follows:

(1) The concentration of free radicals in coal samples increased with the increase in the oxidation temperature, and there was a certain range of fluctuation in the increase process, especially in lignite. The changes in the free radical concentrations showed a significant relationship with the metamorphic degree of coal. The free radical concentrations of anthracite and bituminous coal, which have a higher metamorphic degree, were large and increased gently. The free radical concentration of lignite increased rapidly after 90 °C and then exceeded that of anthracite and bituminous coal. The g-factor value and line width of the coal samples varied greatly across the different types of coal. The change range of the g-factor value decreased with the increase in the metamorphism of the coal sample. The change range of lignite was the largest during oxidation, followed by bituminous coal; the change rate of anthracite was the smallest. With the increase of oxidation temperature, the line width of bituminous coal decreased gradually, while the line width of anthracite and lignite changed little.

(2) The side chains of aliphatic hydrocarbons of coal samples with a low metamorphic degree decreased to varying degrees in the initial heating stage; then, their content fluctuated significantly as the oxidation temperature increased. The content of −OH in bituminous coal and lignite tended to increase first and then decrease, while that in anthracite tended to decrease first and then increase. In the primary stage of oxidation, the higher the metamorphic degree of coal, the greater the reduction range of the content of −OH. The change trend for −COOH in the three kinds of coal samples was generally consistent; in the initial oxidation stage, it first increased rapidly and then decreased rapidly, then increased and finally decreased, and the amplitude of the latter increase and decrease was significantly smaller than that of the first change. In the initial oxidation stage, the content of −C=O in bituminous coal and lignite increased, while that in lignite, which has a lower metamorphic degree, increased the fastest. This indicates that −C=O is mainly generated by the oxidation of the aliphatic hydrocarbon side chain.

(3) Gray relational analysis showed that there was an obvious relationship between free radicals and functional groups during low-temperature oxidation. The relational grades between different functional groups and free radicals was quite different in anthracite and bituminous coal. But the difference was very small in lignite. Among the functional groups, −OH had the largest relational grade with free radicals, indicating that the relationship between them was the closest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial support of project nos. 51974015 and 51474017 provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China; project no. SMDPC202101 provided by the Key Laboratory of Mining Disaster Prevention and Control (Shandong University of Science and Technology); project nos. FRF-IC-20-01 and FRF-IC-19-013 provided by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities; project no. 2018YFC0810601 provided by the National Key Research and Development Program of China; project no. 2017CXNL02 provided by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (China University of Mining and Technology); project no. WS2018B03 provided by the State Key Laboratory Cultivation Base for Gas Geology and Gas Control (Henan Polytechnic University); project no. E21724 provided by the Work Safety Key Lab on Prevention and Control of Gas and Roof Disasters for Southern Coal Mines of China (Hunan University of Science and Technology); and the independent technology project “Technical Research” of Huaneng Coal Industry Co., Ltd.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Song Z. Y.; Kuenzer C. Coal fires in China over the last decade: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 133, 72–99. 10.1016/j.coal.2014.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Huang W. H.; Ao W. H.; Teng J. Analysis on the Factors Affecting the Spontaneous Combustion of Coal in China. Coal Sci. Technol. 2013, 41, 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. N.; Shu P.; Deng J.; Duan Z. J.; Li L. L.; Zhang L. L. Analysis of oxidation pathways for characteristic groups in coal spontaneous combustion. Energy 2022, 254, 124211. 10.1016/j.energy.2022.124211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X. Q.; Zhang Y. T.; Chen X. K.; Zhang Y. B. Effects of thermal boundary conditions on spontaneous combustion of coal under temperature-programmed conditions. Fuel 2021, 295, 120591. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V.; Gupta R. P.; Arora M. K. Environmental impact studies in coalfields in India: A case study from Jharia coal-field. Renew. Sust. Energy. Rev. 2016, 53, 1222–1239. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X.; Deng J.; Xiao Y.; Zhai X. W.; Wang C. P.; Yi X. Recent progress and perspective on thermal-kinetic, heat and mass transportation of coal spontaneous combustion hazard. Fuel 2022, 308, 121234. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. M. K.; Henke K. R.; Hower J. C.; Engle M. A.; Stracher G. B.; Stucker J. D.; Drew J. W.; Staggs W. D.; Murray T. M.; Hammond M. L.; Adkins K. D.; Mullins B. J.; Lemley E. W. CO2, CO, and Hg emissions from the Truman Shepherd and Ruth Mullins coal fires, eastern Kentucky, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 1628–1633. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. L.; Han Y. X.; Li Y. J.; Li W. B.; He J. C.; Jin J. P. Strengthening the flotation recovery of silver using a special ceramic-medium stirred mill. Powder Technol. 2022, 406, 117585. 10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Qin Z. H.; Bu L. H.; Yang Z.; Shen C. Y. Structural analysis of functional group and mechanism investigation of caking property of coking coal. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2016, 44, 385–393. 10.1016/S1872-5813(16)30019-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. H.; Li Z. H.; Yang Y. L.; Wang C. J. Study on oxidation and gas release of active sites after low-temperature pyrolysis of coal. Fuel 2018, 233, 237–246. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu N. S.; Li H. L.; Jin Z. J.; Zhu Y. K. Temperature and time effect on the concentrations of free radicals in coal: Evidence from laboratory pyrolysis experiments. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2007, 69, 220–228. 10.1016/j.coal.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. X.; Jiang X. M.; Shen J.; Zhang H. Chemical properties of superfine pulverized coal particles. Part 1. Electron paramagnetic resonance analysis of free radical characteristics. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 916–925. 10.1016/j.apt.2014.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. X.; Jiang X. M.; Han X. X.; Shen J.; Zhang H. Chemical properties of superfine pulverized coals. Part 2. Demineralization effects on free radical characteristics. Fuel 2014, 115, 685–696. 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.07.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. X.; Jiang X. M.; Shen J.; Zhang H. Influences of particle size, ultraviolet irradiation and pyrolysis temperature on stable free radicals in coal. Powder Technol. 2015, 272, 64–74. 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. Z.; Yang S. Q.; Wang C. J.; Hu X. C.; Song W. X.; Cai J. W.; Xu Q.; Sang N. W. The characterization of free radical reaction in coal low-temperature oxidation with different oxygen concentration. Fuel 2020, 262, 116524. 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. C.; Yu Z. Y.; Cai J. W.; Jiang X. Y.; Li P.; Yang S. Q. The influence of methane on the development of free radical during low-temperature oxidation of coal in gob. Fuel 2022, 330, 125369. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. Z.; Yang S. Q.; Jiang X. Y.; Song W. X. Experimental study on oxygen adsorption capacity and oxidation characteristics of coal samples with different particle sizes. Fuel 2023, 331, 125954. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X. Y.; Yang S. Q.; Zhou B. Z.; Hou Z. S.; Zhang C. S. Effect of gas atmosphere change on radical reaction and indicator gas release during coal oxidation. Fuel 2022, 312, 122960. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. T.; Zhang J.; Li Y. Q.; Gao S.; Yang C. P.; Shi X. Q. Oxidation Characteristics of Functional Groups in Relation to Coal Spontaneous Combustion. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 7669–7679. 10.1021/acsomega.0c06322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. J.; Xu Y. L.; Wen X. L.; Lv Z. G.; Wu J. D.; Li M. J.; Wang L. Y. Thermal Properties and Key Groups Evolution of Low-Temperature Oxidation for Bituminous Coal under Lean-Oxygen Environment. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 15115–15125. 10.1021/acsomega.1c01338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X. Y.; Wang D. M.; Xin H. H.; Qi G. S. In Situ FTIR Study of Real-Time Changes of Active Groups during Oxygen-Free Reaction of Coal. Energy Fuel. 2013, 27, 3130–3136. 10.1021/ef400534f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L.; Wang P.; Li S. G.; Lin H. F.; Zhao P. X.; Ma C.; Yang E. H. Gas Adsorption Capacity of Coal Frozen with Liquid Nitrogen and Variations in the Proportions of the Organic Functional Groups on the Coal after Freezing. Energy Fuel. 2021, 35, 1404–1413. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c04035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z. Y.; Liu G. J.; Yin H.; Zhou C. C.; Wu D.; Tan F. F. A comparative study on thermal behavior of functional groups in coals with different ranks during low temperature pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2021, 158, 105258. 10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. L.; Li X.; Xi K. Study on the reactivity of oxygen-containing functional groups in coal with and without adsorbed water in low-temperature oxidation. Fuel 2021, 304, 121454. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. L.; Tahmasebi A.; Dou J. X.; Lee S.; Li L. C.; Yu J. L. Influence of functional group structures on combustion behavior of pulverized coal particles. J. Energy Inst. 2020, 93, 2124–2132. 10.1016/j.joei.2020.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. Z.; Yang S. Q.; Jiang X. Y.; Cai J. W.; Xu Q.; Song W. X.; Zhou Q. C. The reaction of free radicals and functional groups during coal oxidation at low temperature under different oxygen concentrations. Process Saf. Environ. 2021, 150, 148–156. 10.1016/j.psep.2021.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Yang S. Q.; Hu X. C.; Song W. X.; Cai J. W.; Zhou B. Z. Low-temperature oxidation of free radicals and functional groups in coal during the extraction of coalbed methane. Fuel 2019, 239, 429–436. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.11.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Yang S. Q.; Cai J. W.; Zhou B. Z.; Xin Y. N. Risk forecasting for spontaneous combustion of coals at different ranks due to free radicals and functional groups reaction. Process Saf. Environ. 2018, 118, 195–202. 10.1016/j.psep.2018.06.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Yang S. Q.; Yang W. M.; Tang Z. Q.; Hu X. C.; Song W. X.; Zhou B. Z.; Yang K. Secondary oxidation of crushed coal based on free radicals and active groups. Fuel 2021, 290, 120051. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.120051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y.; Gao K.; Hu J. J.; Liu Y. H. Insight into the low-temperature oxidation behavior of coal undergone heating treatment in N2. Fuel 2022, 330, 125628. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei A. Z.Experimental study on the mechanism of coal spontaneous combustion free radical reaction; China University of Mining and Technology, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. S.; Liou F. M.; Huang C. P. Grey forecasting model for CO2 emissions: A Taiwan study. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3816–3820. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. W.; Lei T. Z.; Chang X.; Shi X. G.; Xiao J.; Li Z. F.; He X. F.; Zhu J. L.; Yang S. H. Optimization of a biomass briquette fuel system based on grey relational analysis and analytic hierarchy process: A study using cornstalks in China. Appl. Energy 2015, 157, 523–532. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.04.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. B.; Zhang Y. T.; Li Y. Q.; Shi X. Q.; Xia S. W.; Guo Q. Determination and dynamic variations on correlation mechanism between key groups and thermal effect of coal spontaneous combustion. Fuel 2022, 310, 122454. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W.; Cao X. K.; Fang J.; Chang J. M.; Wei Y. D.; Li X.; Li Y.; Zheng Z. G.; Zhao J. Y.; Song J. J.; Lu S. P. Correlation Analysis of the Change Law of Index Gas and Active Functional Groups in the Process of High-Temperature Spontaneous Combustion of Minerals in the Fushun West Mine. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33199–33215. 10.1021/acsomega.2c03562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Y.; Wang T.; Deng J.; Shu C. M.; Zeng Q.; Guo T.; Zhang Y. X. Microcharacteristic analysis of CH4 emissions under different conditions during coal spontaneous combustion with high-temperature oxidation and in situ FTIR. Energy 2020, 209, 118494. 10.1016/j.energy.2020.118494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. P.; Xiao Y.; Li Q. W.; Deng J.; Wang K. Free radicals, apparent activation energy, and functional groups during low-temperature oxidation of Jurassic coal in Northern Shaanxi. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 469–475. 10.1016/j.ijmst.2018.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]