Abstract

The chemical toolbox for the selective modification of proteins has witnessed immense interest in the past few years. The rapid growth of biologics and the need for precision therapeutics have fuelled this growth further. However, the broad spectrum of selectivity parameters creates a roadblock to the field’s growth. Additionally, bond formation and dissociation are significantly redefined during the translation from small molecules to proteins. Understanding these principles and developing theories to deconvolute the multidimensional attributes could accelerate the area. This outlook presents a disintegrate (DIN) theory for systematically disintegrating the selectivity challenges through reversible chemical reactions. An irreversible step concludes the reaction sequence to render an integrated solution for precise protein bioconjugation. In this perspective, we highlight the key advancements, unsolved challenges, and potential opportunities.

Short abstract

The DIN theory provides a systematic tool to disintegrate the selectivity challenges in protein bioconjugation, followed by the integration of their solutions using a combination of chemical reactions.

Introduction

The synchronized coordination of events within biomolecules regulates human health. In this pool, proteins have served as valuable candidates as both therapeutics1 and targets.2 While the former requires labeling in isolated form, the latter depends on their selective targeting in a complex biological milieu. The screening-driven drug discovery processes remain the preferred routes for the latter.3 Further, proteome-wide chemoproteomics has accelerated the segment by establishing selective probes and new targets.4,5 On the other hand, the data also provide insight into considerable drug promiscuity and its implications.6 These developments highlight the need for principles to regulate selectivity in protein modification.

In this direction, we first need the tools and methods that can allow us to control selectivity with isolated proteins. Next, we can translate them sequentially from one system to another (Figure 1a). In the process, we can understand the impact of the complexity added by the microenvironment layers within cells, tissues, animals, and humans. This approach can complement the ongoing efforts to develop covalent regulators and inhibitors.7−9 Besides, controlling selectivity with isolated proteins, enzymes, and antibodies would empower biologics.10−14 The overlap of knowledge between segments at the two ends of the complexity scale, from small molecules to humans, must evolve with time to meet the technological demands.

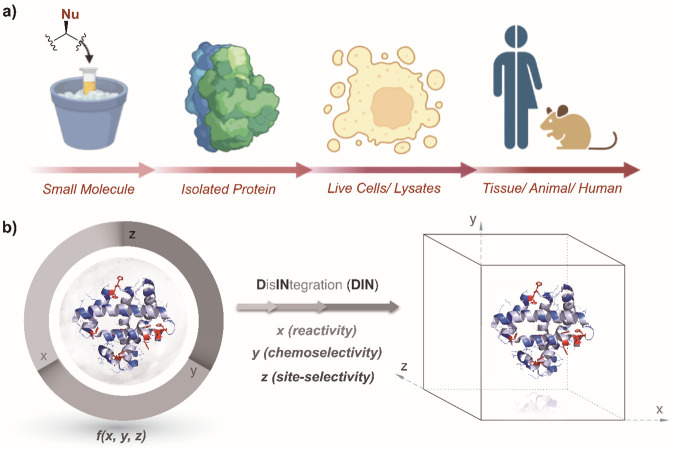

Figure 1.

(a) The microenvironment of a functionality (nucleophile, Nu) from small molecules to a complex protein-based social ecosystem. (b) DIN theory: the disintegration of reaction attributes and their independent regulation can empower the integration of solutions for the precision engineering of native proteins.

Revisiting this problem from the end of small-molecule substrates provides another perspective. It initiates with chemical bond formation between two reactive partners, such as nucleophiles and electrophiles (Figure 1a). With a limited number of variables, the characteristics of such organic transformations are predictable. However, the behavior spectrum broadens once additional functional groups accompany the nucleophile. As a simple example, the bond-formation capabilities of a primary amine in n-butyl amine, a Lys-bearing peptide, and a Lys-bearing protein could be substantially different. The trend continues with additional layers added to the functional group ecosystem (Figure 1a). Can we have a theory to deconvolute the spectrum of a functional group’s behavior in a complex social environment? It could promote hypothesis-driven research and bring a larger protein landscape within the purview of selective modification. A chemical method for the precise single-site modification of an isolated protein needs to cross three critical barriers (Figure 1b). Initially, the reagent requires a reasonable reactivity at a low substrate concentration (x-axis). Next, the reagent must distinguish one functional group from others (chemoselectivity, y-axis). Finally, such a chemoselective reagent should be able to distinguish one copy of a residue from its multiple copies to display site selectivity (z-axis). As we move forward, the modularity beyond protein-defined reactivity order, site or residue specificity, and protein specificity can offer additional dimensions.

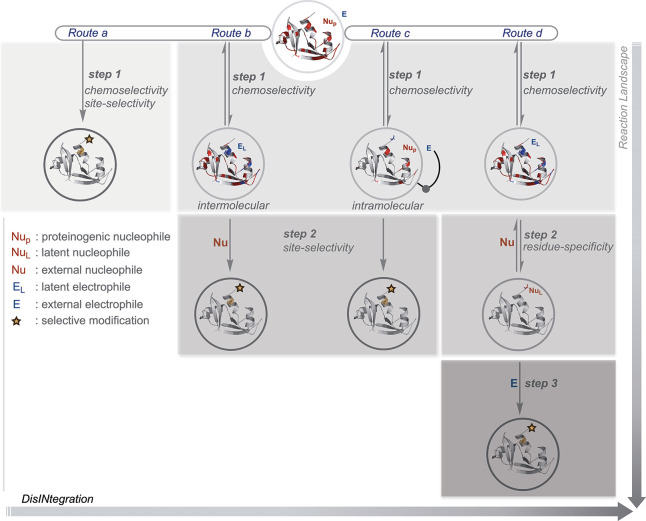

In this outlook, we argue that the selectivity attributes can be disintegrated through a multistep chemical transformation (DIN theory, Figure 2). Under such a case, the tuning of the selectivity attributes, such as chemoselectivity and site selectivity, can be done independently. Besides, such a deconvolution can create a redefined reactivity landscape of proteins to label residues beyond the hotspots, which are sites that offer the best combination of reactivity and solvent accessibility. In this perspective, Route A presents examples that address all the selectivity challenges in a single step (Figure 2).15,16 Subsequently, Route B outlines how chemoselectivity and site selectivity can be disintegrated into two steps. In the process, it redefines the reactivity landscape and hotspots. Further, Route C demonstrates how such multistep deconvolutions can offer a modular platform. Finally, we strengthen the argument through Route D, which demonstrates the segregation of chemoselectivity and residue-specificity for single-site protein bioconjugation. While the general sections are directed toward a broad readership, the exemplification would benefit the researchers in the field. Overall, it demonstrates how DIN theory could empower hypothesis-driven research to find new selectivity attributes and target unique sites/domains that have not been accessible to precision protein engineering technologies.

Figure 2.

Disintegration of selectivity attributes through chemical steps redefines the reactivity landscape to enable single-site protein modification. (a) Targeting reactivity hotspots in one step. (b) A two-step process, reversible intermolecular and irreversible intermolecular, can deconvolute chemoselectivity and site selectivity to render redefined reactivity hotspots. (c) A two-step process, reversible intermolecular and irreversible intramolecular, can offer modularity in addition to chemoselectivity and site selectivity deconvolution. (d) A multistep process can deconvolute chemoselectivity and residue specificity. The selected routes a–d show representative possibilities and can be extended to other reagent and intermediate combinations.

Route A

The initial efforts for the precision labeling of proteins involved addressing all the selectivity attributes in a single step (route a, Figure 2). Typically, such transformations would apply an irreversible chemical transformation. However, there are examples where a reversible step regulates both chemoselectivity and site selectivity, while an irreversible transformation would render the product. In both cases, proteinogenic residues’ inherent reactivity order and solvent accessibility determine the modification site. Consequently, such methods offer a narrow range of reaction parameters under which absolute single-site selectivity can be achieved. Such methods engage only a single residue for its irreversible transformation in the overall process. Additionally, the bioconjugation reagent’s size, structure, and binding preferences could also contribute. On the other hand, the protein’s structure plays a defining role in establishing the reactivity hotspots. Its perturbation provides a gateway to access the low-frequency residues with limited solvent accessibility. Although, the same would compromise the site selectivity for high-frequency residues. The protein bioconjugation methods in this Outlook were primarily developed under nondenaturing physiological conditions unless specified.17,18

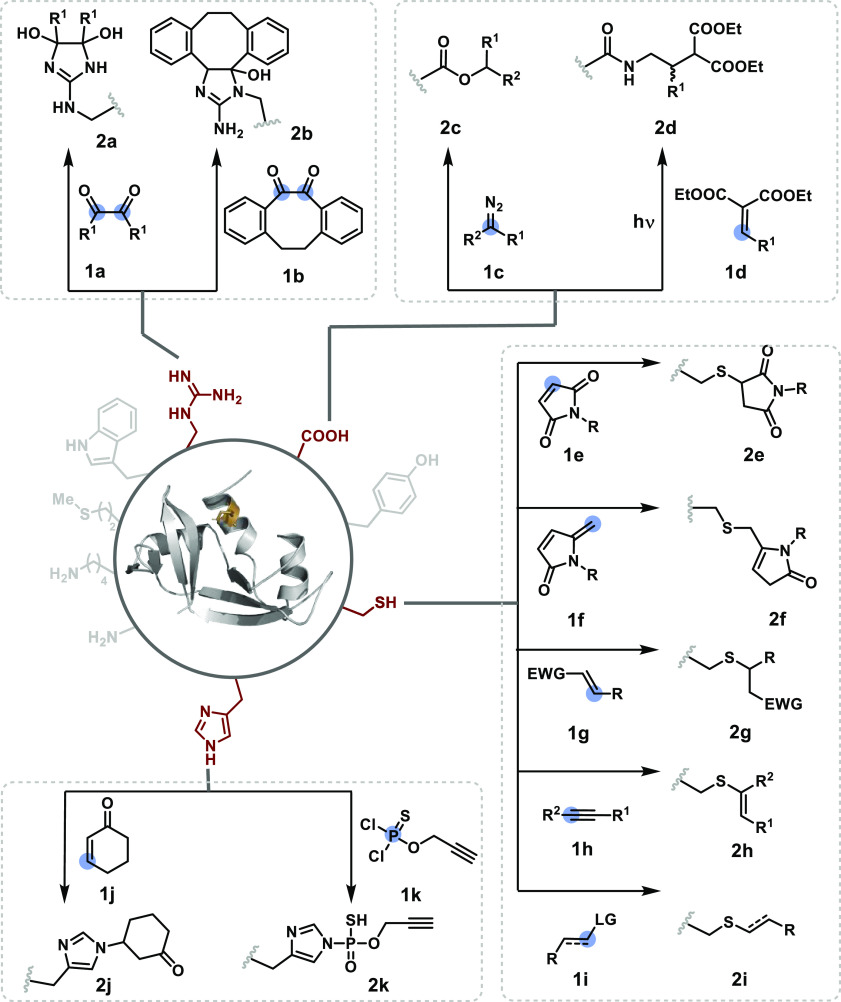

The nucleophilic functionalities in a protein are also basic in nature. Their pKa values determine the concentration of their deprotonated or nucleophilic form in the reaction mixture. In turn, it contributes to their reactivity order. For example, Arg is largely protonated under physiological conditions. Its reaction with diketones (1a, Figure 3), e.g., cyclohexanedione, typically requires alkaline conditions.19 The side-chain guanidine and cyclohexanedione result in irreversible Arg modifications. However, the elevated pH also activates multiple Lys and His residues. Hence, the Arg modifications are often accompanied by chemoselectivity challenges. The dibenzocyclooctendione (1b) motif creates an opportunity for irreversible benzylic rearrangement after the nucleophilic addition of Arg.20 The interplay of reversible and irreversible pathways adds another dimension to chemoselectivity. For example, oxoaldehyde reacts with Lys in a kinetically preferred transformation. However, Arg delivers a thermodynamically stable product, while the Lys adduct reverts through transoximization with hydroxylamine.21

Figure 3.

Targeting reactivity hotspots in one step: efforts with Arg, carboxylates, Cys, and His.

Unlike Arg, carboxylic acid remains in deprotonated carboxylate form under physiological conditions. However, its low nucleophilicity makes it very difficult to target with chemoselectivity. Besides, its high abundance creates a roadblock to site selectivity. For example, esterification with diazo compounds (1c) can lead to the labeling of multiple carboxylates without distinguishing Asp, Glu, and C-terminus CO2H (2c).22,23 On the other hand, the oxidation potential differences between C-terminal and side-chain carboxylates enabled site-selective C-terminal radical generation (2d).24 An α,β-unsaturated ester traps the relatively high-energy C-radical to render the bioconjugate. Even though the oxidative conditions or electrophilic system can compromise the extent of conjugation, it is a positive step toward the selective targeting of a residue with low reactivity.

Cysteine offers the other end with respect to carboxylates, both in terms of occurrence and reactivity. Its low frequency often means that the site selectivity is not applicable for achieving single-site protein bioconjugation. On the other hand, chemoselectivity can be achieved with a range of soft electrophiles. Multiple polarized double bonds have been identified from this perspective. For example, the conjugate addition using maleimide derivatives has been explored extensively for Cys modification (1e).25−27 However, the inherent reversibility of C–S bonds results in thiol exchange and could compromise the chemoselectivity and site selectivity. These challenges have been addressed by regulating the reactivity through subtle changes in the electrophile. For example, incorporating bromine,25 an exocyclic double bond,28 and the hydrolysis of the product29 has offered bioconjugates with higher stability. If an exocyclic double bond replaces the maleimide carbonyl, the 1,4-addition and subsequent reduction yield the bioconjugate over pH 6.0–8.5 (1f).30,31 However, such methylene pyrrolones are susceptible to retro-Michael addition and thiol exchange under basic conditions. In another set of electrophiles, the carbonyl acrylates32 offer better stability than azidoacrylates.33 Additionally, the vinylpyridinium salts offer irreversible Cys modification with negligible competition from Lys.34 Besides, the isoxazolinium ring uses intramolecular rearrangement and fragment release to render a stable and site-selective Cys adduct.35 The polarized double bonds equipped with electron-withdrawing groups also offer pKa regulation to avoid retro-Michael addition, such as vinyl sulphone derivatives (1g).36 Polarized triple bonds, such as alkynoic amides, esters, and alkynones, offer another possibility (1h).37 In particular, they are preferred when the application needs cleavable reagents. An unsaturated vinyl sulfide linkage is created in such cases that undergoes an addition–elimination sequence in the presence of an external thiol. The positions of the alkyne, terminal or internal, and the electron-withdrawing functionality regulate their reactivity. For example, an internal alkyne polarized between aryl and cyano groups offers hydrolytically stable reagents.38 The alkylation reactions offer another opportunity for chemoselective Cys bioconjugation (1i). The nucleophilic substitution of halogens such as bromine (bromooxetane)39 or chlorine (chlorofluoroacetamides)40 occurs under mild conditions. However, a few bromooxetane derivatives require higher pH (8–11) and an organic solvent. The nucleophilic aromatic substitution with benzothiazole41 or chlorotetrazine42 also renders Cys selectivity, with some challenges from Lys. In a mechanistically different route, a free radical-mediated pathway can render thio-ene-43 and thio-yne-based44 Cys modifications. The former involves the photoinduced coupling of alkenyl glycosides with the thiol group. On the other hand, thio-yne coupling proceeds by the addition of two thiol-based free radicals to a terminal alkyne. The vinyl sulfide intermediate formed by the addition of the first thiol is captured by a second thiol via a thio-ene mechanism. However, both methods also engage other residues, including disulfide bonds, and impact the structural integrity of the protein.

The reversibility becomes even more prominent with the His side chain due to the inherently labile imidazole-based N–C bond. This moderate frequency residue with low reactivity poses a stern challenge for single-site modification. Substantial competition from Cys and Lys is unavoidable in most cases. Despite this, the prominent role of His in biological pathways makes it a valuable target.45 The reversibility of the His-based Michael adduct can be reduced by altering the pKa of the β-proton through a functional group transformation.46 However, such an approach does not address the chemoselectivity. Interestingly, cyclohexenone (2j)47 and thiophosphorodichloridates (2k)48 offer noteworthy control over chemoselectivity and site selectivity for single-site His modification.

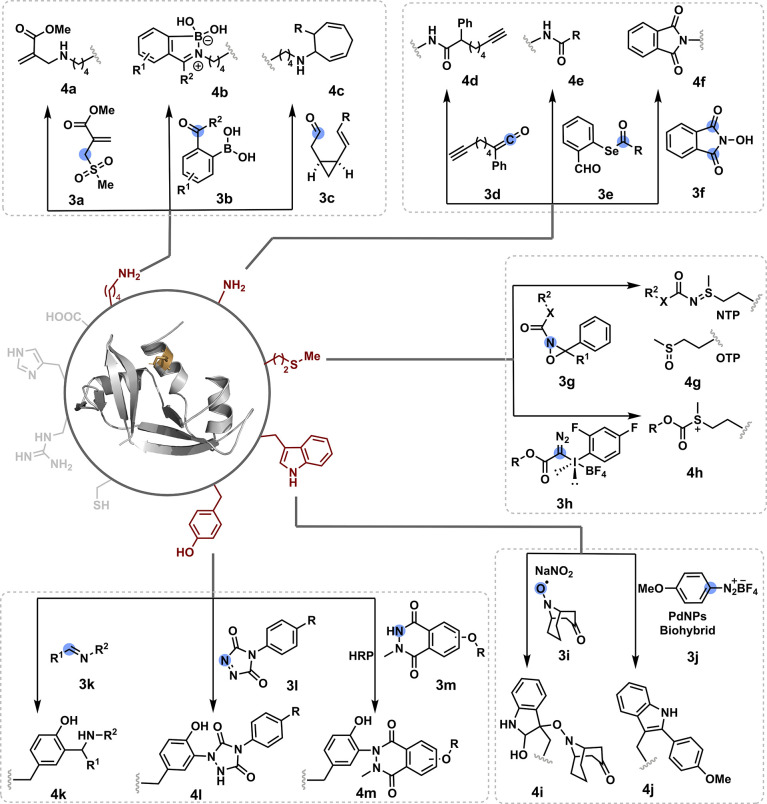

Unlike His, multiple electrophiles have been established to display high chemoselectivity toward the N-terminus α-amine (Nα-NH2) and the Lys ε-amine (Nε-NH2). Cys is a prominent competitor for amines. However, the differences in hardness, pKa, and occurrence frequency enable their exclusive bioconjugation. The pKa difference also makes Nα-NH2 a preferred target over Nε-NH2 under physiological conditions. The charged state ensures enhanced solvent accessibility for this high-frequency residue, making site selectivity a daunting task. Amine modification is often dominated by addition and substitution reactions. Amine acylation with NHS ester derivatives is one of the most frequently employed methods.49 The stability of an amide bond compared to that of a Cys-based thioester enables the formation of chemoselective product. However, such methods cannot distinguish between Nα-NH2 and Nε-NH2. pH fine-tuning or the controlled addition of an NHS ester could deliver a site-selective Nα-NH2 modification.50 The other C-centered amine-selective electrophiles include dichlorotriazine,51 sulfonyl acrylate (3a, Figure 4),52 and allyl isothiocyanate.53 The reversibly formed adducts with amine have also been exploited through subsequent stabilization or an irreversible reaction for chemoselective bioconjugation. For example, imines from a protein were trapped as iminoboronates (3b).54 In another case, the generated imine was designed for an irreversible [3 + 3] cycloaddition (3c).55 The o-ester-substituted arenediazonium reacts with the amine to generate an unstable triazine adduct. Next, an intramolecular reaction generates a stable benzotriazinone derivative.56 The site selectivity presents a substantial challenge in most of these cases. However, blocking Nε-NH2 through acidic reaction conditions could create an opportunity for N-terminus labeling. For example, this approach enabled a ketene to render single-site Nα-NH2 labeling (3d).57 In a distinct approach, a hemiaminal formed between Nα-NH2 and aryl aldehyde with ortho-selenoester enables the N-terminus modification (3e).58 Further, we demonstrated that a proximally placed electrophile could site-selectively capture the Nα-NH2 imine.59 In another example, N-hydroxypthalimide achieves the site-selective Nα-NH2 modification by shifting the rate-determining step from an intermolecular to intramolecular process while negating the requirement of slow addition (3f).60 The site-selective Lys modification is not accessible through single-step processes, especially due to the presence of Nα-NH2.

Figure 4.

Targeting reactivity hotspots in one step: efforts with Lys, N-terminus amine, Met, Trp, and Tyr.

Met presents an entirely different scenario with respect to Lys. It is among the most hydrophobic residues and hence is often buried in domains with minimal solvent accessibility. Moreover, it holds the second position from the bottom in the amino acid frequency scale. These attributes make surface-accessible Met residues rare. It is less likely to face site selectivity challenges when available, making it a promising target for single-site modification. As it is prone to oxidation, redox-activated chemical tagging (ReACT) enables selective Met bioconjugation using oxaziridine-based reagents (3g).61,62 Hypervalent iodine reagents also offer promise from this perspective (3h).63 However, selectively modifying Met under mild conditions without perturbing other residues is still problematic.

Principally, Trp falls under a similar category as Met, as it is the least abundant and exhibits minimal surface exposure. Hence, it provides an equally good opportunity for single-site protein bioconjugation. A sterically unhindered and stable nitroxyl radical (ABNO) reacted selectively with Trp by forming a C(3)–O bond with indole (3i).64 In another case, a heterogeneous PdNP biohybrid catalyst allowed indole C(2)–H activation in Trp under physiological conditions (3j).65 The protein (Cal-B) offers two Trp residues on the surface, and careful control of catalyst loading allows the predominant labeling of a single site.

Tyr is the third residue in this category, with a low frequency and limited surface exposure. The C=N and N=N bonds in diverse structural motifs have served as capable electrophilic systems for targeting the phenolic residue of Tyr. For example, Tyr reacts conveniently with an in situ formed imine66 and cyclic imines (3k).67 Besides, the cyclic diazodicarboxamide derivatives have been successfully employed for selective Tyr bioconjugation through the ene-reaction under physiological conditions (3l).68,69 Additionally, a diazonium salt offers an appropriate handle to react with Tyr chemoselectively.70 In another approach, N-methyl luminol derivatives under HRP-catalyzed single-electron transfer (SET) or electrochemically activated SET deliver selective Tyr modification (3m).71,72

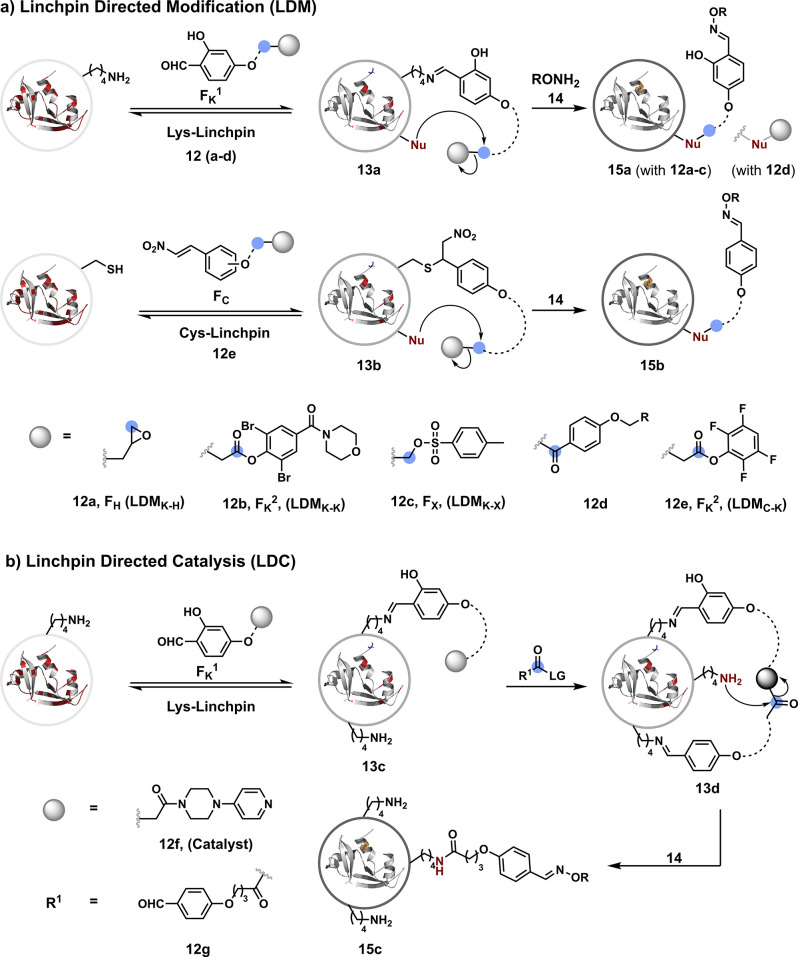

Ligand-Directed Modification

The challenges of addressing reactivity, chemoselectivity, and site selectivity are amplified with large proteins and complex biological mixtures. The ligand–protein interaction driven by reversible covalent or noncovalent binding offers an excellent solution by limiting the number of competitors. Subsequently, the electrophile has a much better opportunity to render a chemoselective and site-selective modification. In this perspective, a benzenesulfonamide ligand tethered to an epoxide (5a, Figure 5) through a linker could deliver the selective labeling of His in human carbonic anhydrase II (hCAII).73 The other initial findings established that varying the linker alters the reactivity and site selectivity of the epoxide in hCAII.74,75 This method offered the additional flexibility of removing the ligand post-bioconjugation. A benzenesulfonamide-linked tosyl group (5e) also offered similar control over selectivity, enabling His alkylation in hCAII.76 The ligand-enabled localization of acyl imidazole (5b) created an opportunity for the selective acylation of a single Lys residue in a protein.77 The same ligand was also utilized to localize a Ru complex ([Ru(bpy)3]2+, 5f), allowing SET photocatalysis for selective Tyr modification.78 The concept has been further extended to the biotin–avidin combination for the selective labeling of Lys using O-nitrobenzoxadiazole (O-NBD, 5d)79 and the diazotransfer reaction with imidazole-1-sulfonyl azide (5c).80 The specificity of the ligand–protein interaction limits the competitors considerably and empowers route a for selective protein modification in a biological milieu such as live cells.

Figure 5.

Ligand-enabled localization reduces competitors and empowers the single step for the selective labeling of proteins.

Route B

The DIN theory deconvolutes the chemoselectivity and site selectivity into two steps. In turn, it could provide enhanced control while addressing these selectivity attributes separately (route b, Figure 2). For example, a reversible first step can render chemoselectivity. In this case, the subsequent irreversible intermolecular reaction will only need to regulate the site selectivity. Besides, the intermediate generated after the first step could redefine the reactivity order. In turn, it opens the opportunity for single-site labeling of reactivity hotspots distinct from route a targets. Such methods could also offer more flexibility with the reaction parameters, at least until the first step.

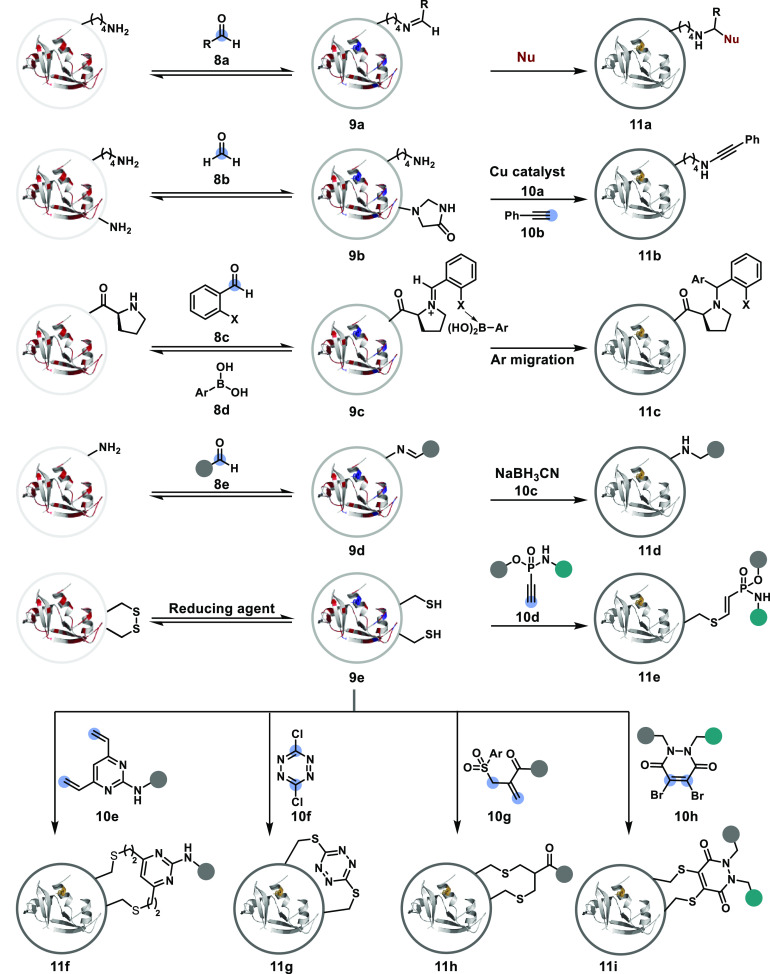

In one of the established examples, the reaction of an aldehyde (8a, Figure 6) derivative with a protein reversibly and chemoselectively creates imine (9a). This step engages multiple solvent-accessible amines. The external nucleophiles can site-selectively capture a single copy of these intermediates. We demonstrated that diethyl phosphite, triethyl phosphite, and t-butyl isocyanide (Nu) could deliver the single-site labeling of Lys residues with a structurally diverse set of proteins (11a).81 The reactivity order of primary amines is mostly redefined when they are converted from their nucleophilic form to imine-based intermediates. Often, this leads to a distinct bioconjugation site. The selection of o-phthalaldehyde can also render stable adducts with external amines.82 However, it is accompanied by competing pathways that create roadblocks for chemoselectivity and site selectivity. On the other hand, the latent electrophilic imine-based intermediates (9b) can be captured site-selectively by the Cu–acetylide complex (11b).83 Interestingly, the Nα-NH2-based imine with selected aldehydes reacts rapidly with the proximal amide bond to produce imidazolidinone (9b). This reversible in situ protection keeps Nα-NH2 out of the competition. Besides, this approach could create conjugation sites distinct from those in route a, confirming the alteration of reactivity hotspots. These methods translate well to large proteins such as monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The approach can also facilitate targeting a proteinogenic secondary amine with high selectivity. For example, an N-Pro-derived iminium intermediate (9c) reacts with an external nucleophile conveniently in a borono-Mannich reaction (11c).84 The Nα-NH2-imine (9d) with certain aldehydes (8e) can also be captured with NaBH3CN (10c).85 However, N-Cys-containing proteins render a mixture of reductive alkylation and thiazolidine-based protein conjugates.

Figure 6.

Route B: a two-step process can deconvolute chemoselectivity and site selectivity to render redefined reactivity hotspots.

In the absence of an accessible free Cys residue, a chemoselective reversible reduction of the disulfide bridge provides a notable alternative. For example, ethynylphosphonamidates (10d) capture the thiolate for antibody modification.86 Further, the reagents with two electrophilic centers add value by rebridging. From this perspective, the reduction (9e) followed by the thiol-selective reaction with divinylpyridine (10e) works well to render the bioconjugate (11f).87 In a principally similar manner, s-tetrazines (10f),88 allyl or aryl sulfones (10g),89−91 and pyridazinedinones (10h)92 render the selective targeting of disulfide bonds. This approach requires caution, as the functionality often contributes to structural stability. For example, disulfide scrambling and heterogeneity are commonly observed with the antibodies.

This disintegration route can also be translated to radical-based intermediates. The C4-alkyl-1,4-dihydroxypyridine reagents can promote photocatalyzed chemoselective His-based radical cation generation.93 In turn, this could deliver an alkylated imidazole residue in the product. In another case, the chemoselective generation of the radical cation with Trp was demonstrated in the presence of N-carbamoylpyridinium salt and UV–B light. The N-centered radical recombines to form a Trp-labeled bioconjugate.94 The site selectivity is not accessible with these high-energy reactive intermediates in general.

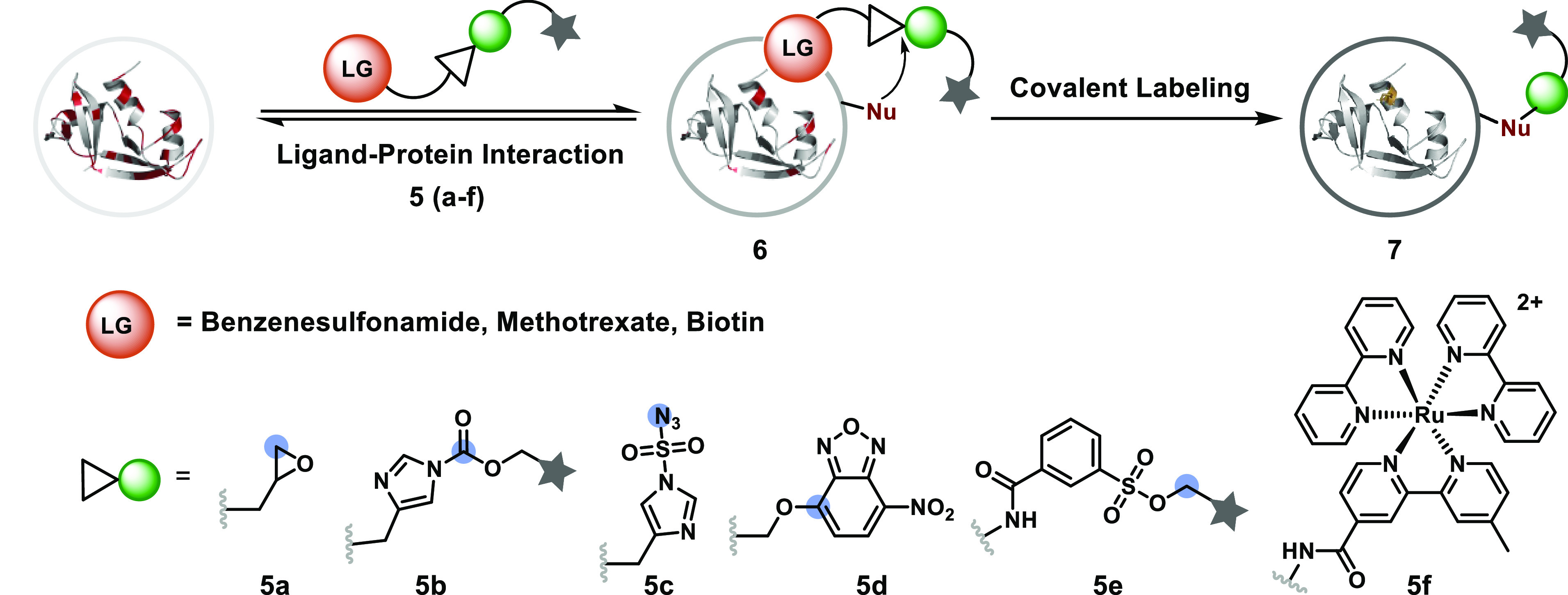

Route C

The deconvolution of chemoselectivity and site selectivity into two steps can also empower a method with additional controls (route c, Figure 2). For example, the reversible and chemoselective first step can be followed by an irreversible intramolecular reaction. Contrary to route b, a pair of proteinogenic residues will regulate the bioconjugation in such a case. Hence, the proximal control could bypass the inherent reactivity order and determine the conjugation site. Such a site-selective method can offer modular single-site protein bioconjugation. Additionally, it creates an opportunity to explore whether two or more residues can create unique signatures in a protein. Since the irreversible final step is intramolecular, such an approach offers a substantial kinetic advantage over the background intermolecular reactions. Hence, this route promises enhanced flexibility with the reaction parameters without compromising the selectivity attributes.

The linchpin-directed modification (LDM) platform provides the proof of concept for this segment. Like route b, it initiates with chemoselective imine formation with all the accessible amines. However, this is where the similarity ends, as the imine does not participate in the subsequent irreversible reaction. It serves as a linchpin and directs another functional group to the proximal residue of interest. The chemoselectivity attributes of the latter and the spacer’s design connecting the two functionalities determine the conjugation site. For example, the o-hydroxybenzaldehyde (FK1, Figure 7a) tethered to an epoxide (12a, FH) through a linker gives a single-site His modification.95 The method offers simultaneous control over reactivity, chemoselectivity, site selectivity, and modularity. At first, FK1 forms an imine (linchpin, 13a) with all the accessible Lys residues in a reversible reaction. It allows the second electrophile (FH) to react irreversibly with a proximal His residue to deliver site-selective labeling (15a). The site selectivity and modularity can be regulated by the spacer design. The aldehyde (FK1) is captured with hydroxylamine (14) for the subsequent installation of probes. The approach also translates well to the lysine-directed single-site modification of a lysine residue (LDMK–K) by replacing the epoxide (FH) with an acylating reagent (12b, FK2).96 The strategy was further extended to selectively label Lys residues in various therapeutically relevant monoclonal antibodies using p-phenol ester (12d) equipped with a linchpin fragment as the leaving group.97,98 The o-hydroxyl group of the linchpin imine makes it highly inert toward the external nucleophiles. It creates an opportunity to use another aromatic aldehyde (FK2) to create the second imine,99 which can be captured in the presence of an external nucleophile to deliver a single-site modification. The LDM platform also extends the site-selective modification of His or Asp using an alkylating reagent such as sulfonate esters (12c, FX).100 Additionally, we demonstrated that nitroolefins could shift the linchpin sites from a high-frequency residue (Lys) to Cys with low occurrence.101 This considerably reduces the number of competitors and creates the opportunity to translate the method for protein selectivity in a complex biological milieu. The nitroolefin (FC) meets all the criteria necessary to create an appropriate linchpin and use FK2 (12e) for the Cys-directed Lys modification (LDMC–K). Here, the chemoselective thio-Michael addition (13b) enables the site-selective Lys acylation (15b). The linchpin’s release from the thio-Michael adduct is coupled with a retro-Henry reaction to render an aldehyde under mild conditions for downstream utility. We anticipated that the geometry and conformation of LDMC–K reagents would regulate the site selectivity. Hence, the protein modification must happen if the distance between the linchpin and the target site matches the FC–FK effective length. Further, the contribution from the dynamics of the protein and the reagent needs to be assessed. In this perspective, the MD simulations offer microscopic insights into the structures and dynamics of these reaction partners. The simulation results validate that the conformational flexibility of the reagent coupled with protein-induced rigidity regulates the effective spacer length and the bioconjugation site. In another validation, the semioxamide vinylogous thioester-based STEF probes offer reversible Cys conjugation to regulate an irreversible site-selective Lys modification.102 A class of cleavable aryl thioethers linked with UV-activatable o-nitrobenzyl alcohol delivers the selective labeling of the Lys residue.103 The modified Cys residue is recovered by thiol exchange in this case. In a recent development, we established that this approach could be extended from a pair of residues to the molecular signatures composed of three residues (Figure 7b).104 It required disintegrating the acylating reagent into two components, the catalyst (12f) and the proelectrophile (12g), both of which were equipped with a linchpin handle for proximity control (LDC). In a principally similar approach, the reversible complexation of boronic acids (BA) with an antibody’s FC-N-glycan directs the 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP).105 The latter forms N-acylpyridinium intermediate with thioester-based acyl donors to yield the acylation of a proximal Lys residue. Encouraged by the linchpin-guided protein modification platform, 10H-phenoxazine-3,7-dicarboxaldehyde was designed for Tyr modification via photoredox catalysis.106 It would be interesting to see if integrating spacers or linkers in these reagents can add modularity to this chemo- and site-selective method.

Figure 7.

Route C: a two-step process can offer modularity in addition to chemoselectivity and site selectivity deconvolution.

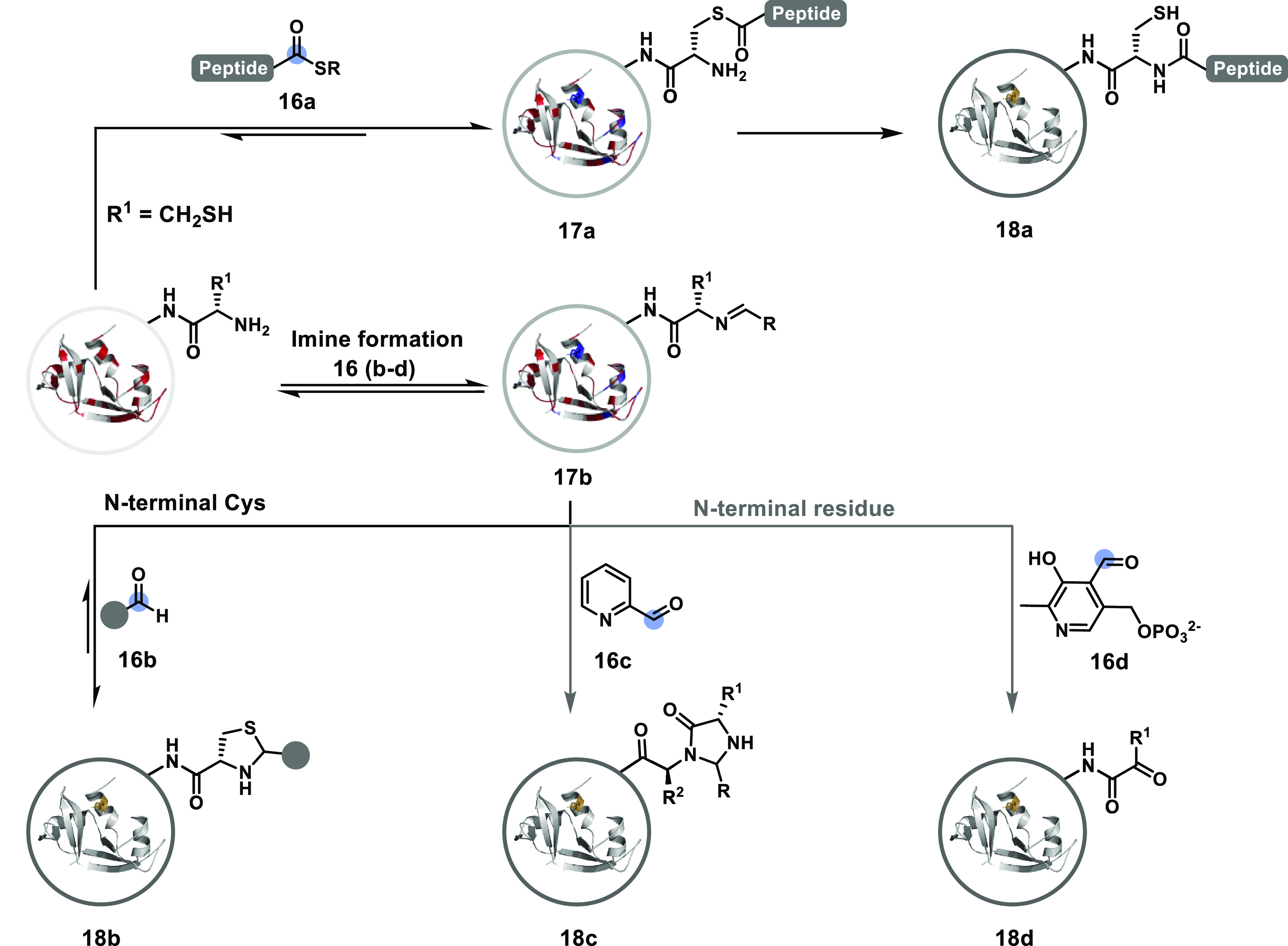

Additionally, targeting a pair of functionalities from the same residue can offer a unique signature to drive selectivity (Figure 8). Nα-NH2 coupled with another functional group, such as the side chain residue of the N-terminal amino acid, offers such an opportunity. For example, the N-Cys protein reacts reversibly with thioesters (16a to 17a) to create an opportunity for an irreversible intramolecular SCys to Nα-NH2 acyl transfer (native chemical ligation, NCL, 18a).107−109 In another case, the N-Cys thiol could capture the Nα-NH2-imine (17b) to render thiazolidine (18b).110 The challenges outlined for C–S bond stability in route a are associated with these adducts. However, they can be addressed to an extent through the use of aldehydes equipped with boronic acids.111 Boronic acid enhances the reaction rate and stabilizes the thiazolidine through the B–N dative bond along with other B-mediated coordination.112 The product stability can also be enhanced by engaging the lone pair on the thiazolidine nitrogen through intramolecular acylation.113 Additionally, the Nα-NH2 can pair with the proximal amide to render selectivity. For example, 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde (2-PCA, 16c)114 or 1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde (TA4C)115 forms an imine that prefers to react with the penultimate amide to yield imidazolidinone (18c). The Lys Nε-NH2-based imine lacks such support to facilitate the irreversible step. Under similar conditions, pyridoxal-5-phosphate (PLP, 16d) generates the Nα-NH2-imine that tautomerizes to render a glyoxyl imine.116 Its hydrolysis yields an aldehyde or ketone (18d) for chemically orthogonal transformations.

Figure 8.

Route C: a two-step process can offer N-terminal specific modification.

Route D

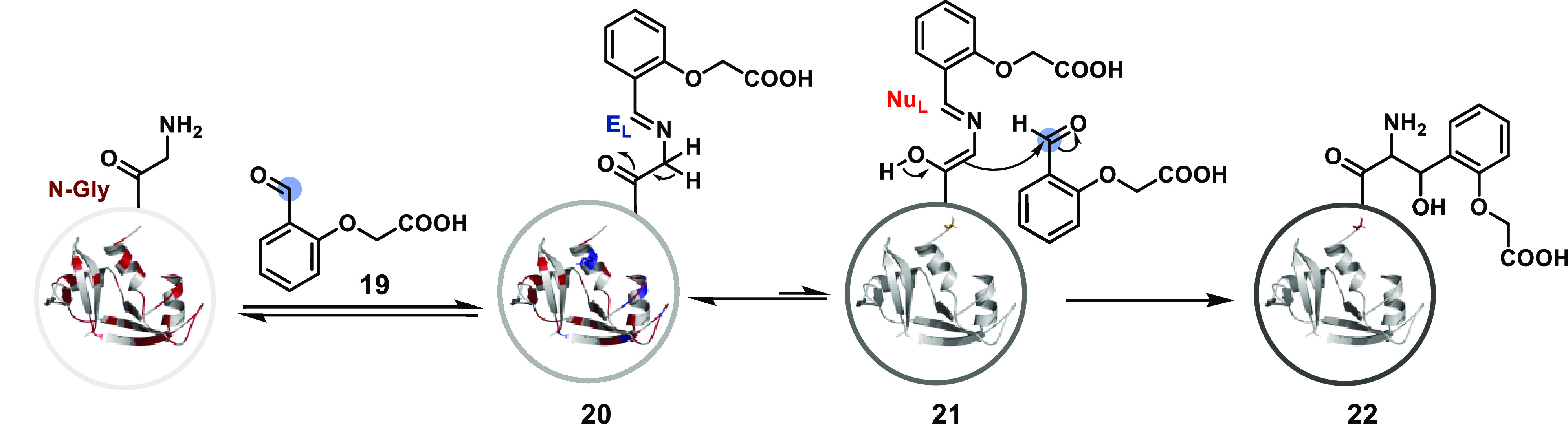

As we noticed in route c, treating the protein with an aldehyde chemoselectively converts a nucleophilic landscape to its electrophilic counterpart. If an additional step can follow this to generate a distinct reactive intermediate, it could disintegrate additional selectivity challenges. For example, we demonstrated that the Nα-NH2-imine (20, Figure 9) with an aromatic aldehyde (19) could generate a nucleophilic intermediate (21).117 A proximal H-bond stabilizer in the aldehyde plays a critical role in the process. It allows the N-terminus Cα-H functionality to be paired with Nα-NH2 and creates a unique signature for bioconjugation. Hence, the Nε-NH2-imine would be excluded from any irreversible transformation. Additionally, the method can distinguish the Cα-H of an unsubstituted amino acid from those of all the substituted analogs. Hence, it offers exclusive N-Gly selectivity and renders precision labeling of proteins without affecting any internal residue. It also enables protein selectivity by distinguishing N-Gly from all the other N-terminal amino acids in a complex mixture of proteins. In another report, the Gly tag technology inspired azido pyridoxal derivatives that delivered residue-specific azidolation.118 Engaging a unique combination of functionalities for an irreversible transformation can offer new gateways for precisely engineered bioconjugates. It would be interesting to see if chemical transformations can harness a Cα-H pKa of another unique residue. Besides, the side chain residues can generate a proximal electrophilic system to engage the Cα-H-enabled nucleophilic intermediate. One can also imagine a side-chain residue to generate an intermediate that can serve as a leaving group in cooperation with Cα-H abstraction. Such a case could lead to the formation of chemically orthogonal dehydroalanine. If extended to an internal residue, these approaches will likely encounter multiple solvent-accessible copies. Hence, the question of N-residue specificity will be redefined to site selectivity.

Figure 9.

Route D: a multistep process can deconvolute chemoselectivity and residue specificity.

Conclusion

Protein bioconjugates have established their immense value at the chemistry–biology–medicine interface. However, chemical methods enabling control over precision are vital to meet the technological demands. This makes it essential to understand the bottlenecks in the development of new routes for selectively modifying proteins. The functional group ecosystem of a protein is complex, and the interplay of multiple operating parameters adds to the challenge. That is why hit-and-trial or directed screening has been a preferred option for developing a new method.

The DIN theory, in this Outlook, argues that the selectivity attributes can be disintegrated through a multistep chemical transformation. In turn, it could enable the exploration of new reactivity dimensions, better prediction of potential products, and hypothesis-driven research. We have outlined three representative routes (b–d) to exemplify how such deconvolutions led to additional selectivity or specificity attributes. It would be interesting to see how new dimensions add to this repertoire with time. The methods addressing all the selectivity attributes in a single step often fall short of site selectivity. Besides, their flexibility and translation for protein selectivity in complex systems are limited. Additionally, the precision in such examples displays a very high sensitivity toward the reaction parameters. The disintegration of chemoselectivity and site selectivity in two intermolecular steps renders a unique reactivity landscape and hotspots for single-site modification. Shifting the latter to an intramolecular step also opens the platform to regulating modularity. Further, the multistep deconvolution could deliver the simultaneous regulation of chemoselectivity, residue specificity, and protein selectivity. Such processes also offer access to a broader reaction parameter window without compromising the overall selectivity.

In the coming years, the DIN theory could encourage the examination of multiple unique reactive intermediates through reversible transformations. In turn, we will have access to distinct reactivity orders leading to unique bioconjugation sites. These findings will likely extend the reach of single-site bioconjugation to low-reactivity residues. It will also be interesting to see if such deconvolutions can empower high-energy intermediates for site-selective modification, contrary to their behavior. We can expect it to accelerate the field’s growth while contributing to the rapidly growing segment of biologics such as ADCs, AFCs, and conjugate vaccines. Besides, such regulations can expedite the discovery of molecules, such as covalent inhibitors, for the selective targeting of a protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by SERB, DST, DBT, SERB-PACE (IPA/2021/000148), and IISER Bhopal. P.C., R.V., M.K., R.M., and U.V.B. are recipients of research fellowships from SERB, CSIR, DST, and IISER Bhopal. V.R. is a recipient of the Swarnajayanti Fellowship (DST/SJF/CSA-01/2018-19 and SB/SJF/2019-20/01). The figures are designed using Pymol, Biorender, and ChemOffice.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Leader B.; Baca Q. J.; Golan D. E. Protein Therapeutics: A Summary and Pharmacological Classification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7 (1), 21–39. 10.1038/nrd2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull S. C.; Doig A. J. Properties of Protein Drug Target Classes. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117955. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. P.; Rees S.; Kalindjian S. B.; Philpott K. L. Principles of Early Drug Discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 162 (6), 1239–1249. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewes G.; Knapp S. Chemoproteomics and Chemical Probes for Target Discovery. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36 (12), 1275–1286. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta J. D.; Peacock D. M.; Zheng Q.; Walker J. A.; Zhang Z.; Zimprich C. A.; Thomas M. R.; Beck M. T.; Binkowski B. F.; Corona C. R.; Robers M. B.; Shokat K. M. KRAS Is Vulnerable to Reversible Switch-II Pocket Engagement in Cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18 (6), 596–604. 10.1038/s41589-022-00985-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanning B. R.; Whitby L. R.; Dix M. M.; Douhan J.; Gilbert A. M.; Hett E. C.; Johnson T. O.; Joslyn C.; Kath J. C.; Niessen S.; Roberts L. R.; Schnute M. E.; Wang C.; Hulce J. J.; Wei B.; Whiteley L. O.; Hayward M. M.; Cravatt B. F. A Road Map to Evaluate the Proteome-Wide Selectivity of Covalent Kinase Inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10 (9), 760–767. 10.1038/nchembio.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boike L.; Henning N. J.; Nomura D. K. Advances in Covalent Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2022, 21 (12), 881–898. 10.1038/s41573-022-00542-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Hwang Y. S.; Kim M.; Park S. B. Recent Advances in the Development of Covalent Inhibitors. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12 (7), 1037–1045. 10.1039/D1MD00068C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdeldayem A.; Raouf Y. S.; Constantinescu S. N.; Moriggl R.; Gunning P. T. Advances in Covalent Kinase Inhibitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49 (9), 2617–2687. 10.1039/C9CS00720B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.; Goetsch L.; Dumontet C.; Corvaïa N. Strategies and Challenges for the next Generation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2017, 16 (5), 315–337. 10.1038/nrd.2016.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal P.; Bertozzi C. R. Site-Specific Antibody–Drug Conjugates: The Nexus of Bioorthogonal Chemistry, Protein Engineering, and Drug Development. Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26 (2), 176–192. 10.1021/bc5004982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragovich P. S. Degrader-Antibody Conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51 (10), 3886–3897. 10.1039/D2CS00141A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashman N.; Bargh J. D.; Spring D. R. Non-Internalising Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51 (22), 9182–9202. 10.1039/D2CS00446A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M.; Reddy N. C.; Rai V. Chemical Technologies for Precise Protein Bioconjugation Interfacing Biology and Medicine. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57 (58), 7083–7095. 10.1039/D1CC02268G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T.; Hamachi I. Chemistry for Covalent Modification of Endogenous/Native Proteins: From Test Tubes to Complex Biological Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (7), 2782–2799. 10.1021/jacs.8b11747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt E. A.; Cal P. M. S. D.; Oliveira B. L.; Bernardes G. J. L. Contemporary Approaches to Site-Selective Protein Modification. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2019, 3 (3), 147–171. 10.1038/s41570-019-0079-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Declas N.; Maynard J. R. J.; Menin L.; Gasilova N.; Götze S.; Sprague J. L.; Stallforth P.; Matile S.; Waser J. Tyrosine Bioconjugation with Hypervalent Iodine. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13 (43), 12808–12817. 10.1039/D2SC04558C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Wang J.; Shao Q.; Shi J.; Zhu W. The Effects of Organic Solvents on the Folding Pathway and Associated Thermodynamics of Proteins: A Microscopic View. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19500. 10.1038/srep19500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toi K.; Bynum E.; Norris E.; Itano H. A. Studies on the Chemical Modification of Arginine: I. The reaction of 1,2-cyclohexanedione with arginine and arginyl residues of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242 (5), 1036–1043. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)96229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih C.-T.; Kuo B.-H.; Tsai C.-Y.; Tseng M.-C.; Shie J.-J. Dibenzocyclooctendiones (DBCDOs): Arginine-Selective Chemical Labeling Reagents Obtained through Benzilic Acid Rearrangement. Org. Lett. 2022, 24 (25), 4694–4698. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier M. A.; Klok H.-A. Arginine-Specific Modification of Proteins with Polyethylene Glycol. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12 (2), 482–493. 10.1021/bm101272g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mix K. A.; Raines R. T. Optimized Diazo Scaffold for Protein Esterification. Org. Lett. 2015, 17 (10), 2358–2361. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath N. A.; Andersen K. A.; Davis A. K. F.; Lomax J. E.; Raines R. T. Diazo Compounds for the Bioreversible Esterification of Proteins. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6 (1), 752–755. 10.1039/C4SC01768D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom S.; Liu C.; Kölmel D. K.; Qiao J. X.; Zhang Y.; Poss M. A.; Ewing W. R.; MacMillan D. W. C. Decarboxylative Alkylation for Site-Selective Bioconjugation of Native Proteins via Oxidation Potentials. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10 (2), 205–211. 10.1038/nchem.2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedaldi L. M.; Smith M. E. B.; Nathani R. I.; Baker J. R. Bromomaleimides: New Reagents for the Selective and Reversible Modification of Cysteine. Chem. Commun. 2009, 43, 6583–6585. 10.1039/b915136b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani G.; Lecolley F.; Tao L.; Haddleton D. M.; Clerx J.; Cornelissen J. J. L. M.; Velonia K. Design and Synthesis of N-Maleimido-Functionalized Hydrophilic Polymers via Copper-Mediated Living Radical Polymerization: A Suitable Alternative to PEGylation Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127 (9), 2966–2973. 10.1021/ja0430999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann E.; Marrian D. H.; Simon-Reuss I. Antimitotic Action Of Maleimide And Related Substances. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1949, 4 (1), 105–108. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1949.tb00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia D.; Malekar P. V.; Parthasarathy M. Exocyclic Olefinic Maleimides: Synthesis and Application for Stable and Thiol-Selective Bioconjugation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (4), 1432–1435. 10.1002/anie.201508118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia D.; Pawar S. P.; Thopate J. S. Stable and Rapid Thiol Bioconjugation by Light-Triggered Thiomaleimide Ring Hydrolysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (7), 1885–1889. 10.1002/anie.201609733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zang C.; An G.; Shang M.; Cui Z.; Chen G.; Xi Z.; Zhou C. Cysteine-Specific Protein Multi-Functionalization and Disulfide Bridging Using 3-Bromo-5-Methylene Pyrrolones. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1015. 10.1038/s41467-020-14757-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhou X.; Xie Y.; Greenberg M. M.; Xi Z.; Zhou C. Thiol Specific and Tracelessly Removable Bioconjugation via Michael Addition to 5-Methylene Pyrrolones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (17), 6146–6151. 10.1021/jacs.7b00670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardim B.; Cal P. M. S. D.; Matos M. J.; Oliveira B. L.; Martínez-Sáez N.; Albuquerque I. S.; Perkins E.; Corzana F.; Burtoloso A. C. B.; Jiménez-Osés G.; Bernardes G. J. L. Stoichiometric and Irreversible Cysteine-Selective Protein Modification Using Carbonylacrylic Reagents. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13128. 10.1038/ncomms13128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyasu S.; Hayashi H.; Xing B.; Chiba S. Site-Specific Dual Functionalization of Cysteine Residue in Peptides and Proteins with 2-Azidoacrylates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28 (4), 897–902. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M. J.; Navo C. D.; Hakala T.; Ferhati X.; Guerreiro A.; Hartmann D.; Bernardim B.; Saar K. L.; Compañón I.; Corzana F.; Knowles T. P. J.; Jiménez-Osés G.; Bernardes G. J. L. Quaternization of Vinyl/Alkynyl Pyridine Enables Ultrafast Cysteine-Selective Protein Modification and Charge Modulation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (20), 6640–6644. 10.1002/anie.201901405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J.-R.; Chung S.-F.; Leung A. S.-L.; Yip W.-M.; Yang B.; Choi M.-C.; Cui J.-F.; Kung K. K.-Y.; Zhang Z.; Lo K.-W.; Leung Y.-C.; Wong M.-K. Chemoselective and Photocleavable Cysteine Modification of Peptides and Proteins Using Isoxazoliniums. Commun. Chem. 2019, 2, 93. 10.1038/s42004-019-0193-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Sanfrutos J.; Lopez-Jaramillo F. J.; Hernandez-Mateo F.; Santoyo-Gonzalez F. Vinyl Sulfone Bifunctional Tag Reagents for Single-Point Modification of Proteins. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75 (12), 4039–4047. 10.1021/jo100324p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu H.-Y.; Chan T.-C.; Ho C.-M.; Liu Y.; Wong M.-K.; Che C.-M. Electron-Deficient Alkynes as Cleavable Reagents for the Modification of Cysteine-Containing Peptides in Aqueous Medium. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15 (15), 3839–3850. 10.1002/chem.200800669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniev O.; Leriche G.; Nothisen M.; Remy J.-S.; Strub J.-M.; Schaeffer-Reiss C.; van Dorsselaer A.; Baati R.; Wagner A. Selective Irreversible Chemical Tagging of Cysteine with 3-Arylpropiolonitriles. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25 (2), 202–206. 10.1021/bc400469d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutureira O.; Martínez-Sáez N.; Brindle K. M.; Neves A. A.; Corzana F.; Bernardes G. J. L. Site-Selective Modification of Proteins with Oxetanes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (27), 6483–6489. 10.1002/chem.201700745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo N.; Fuchida H.; Sato M.; Watari K.; Shibata T.; Kuwata K.; Miura C.; Okamoto K.; Hatsuyama Y.; Tokunaga K.; Sakamoto S.; Morimoto S.; Abe Y.; Shiroishi M.; Caaveiro J. M. M.; Ueda T.; Tamura T.; Matsunaga N.; Nakao T.; Koyanagi S.; Ohdo S.; Yamaguchi Y.; Hamachi I.; Ono M.; Ojida A. Selective and Reversible Modification of Kinase Cysteines with Chlorofluoroacetamides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15 (3), 250–258. 10.1038/s41589-018-0204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.; Devarie-Baez N. O.; Li Q.; Lancaster J. R. Jr.; Xian M. Methylsulfonyl Benzothiazole (MSBT): A Selective Protein Thiol Blocking Reagent. Org. Lett. 2012, 14 (13), 3396–3399. 10.1021/ol301370s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canovas C.; Moreau M.; Bernhard C.; Oudot A.; Guillemin M.; Denat F.; Goncalves V. Site-Specific Dual Labeling of Proteins on Cysteine Residues with Chlorotetrazines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (33), 10646–10650. 10.1002/anie.201806053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondoni A.; Massi A.; Nanni P.; Roda A. A New Ligation Strategy for Peptide and Protein Glycosylation: Photoinduced Thiol–Ene Coupling. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15 (43), 11444–11449. 10.1002/chem.200901746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader H.; Cross L. C.; Heilbron I.; Jones E. R. H. 132. Researches on Acetylenic Compounds. Part XVIII. The Addition of Thiolacetic Acid to Acetylenic Hydrocarbons. The Conversion of Monosubstituted Acetylenes into Aldehydes and 1 : 2-Dithiols. J. Chem. Soc. 1949, 619–623. 10.1039/jr9490000619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Ma H.; Dong S.; Duan X.; Liang S. Selective Labeling of Histidine by a Designed Fluorescein-Based Probe. Talanta 2004, 62 (2), 367–371. 10.1016/j.talanta.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora R.; Alaiz M.; Hidalgo F. J. Modification of Histidine Residues by 4,5-Epoxy-2-Alkenals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999, 12 (7), 654–660. 10.1021/tx980218n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P. N.; Rai V. Single-Site Labeling of Histidine in Proteins, on-Demand Reversibility, and Traceless Metal-Free Protein Purification. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (8), 1100–1103. 10.1039/C8CC08733D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S.; He D.; Chang C. J. Bioinspired Thiophosphorodichloridate Reagents for Chemoselective Histidine Bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (18), 7294–7301. 10.1021/jacs.8b11912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhof S.; Sinz A. Chances and Pitfalls of Chemical Cross-Linking with Amine-Reactive N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 392 (1), 305–312. 10.1007/s00216-008-2231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Muthoosamy K.; Pfisterer A.; Neumann B.; Weil T. Site-Selective Lysine Modification of Native Proteins and Peptides via Kinetically Controlled Labeling. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23 (3), 500–508. 10.1021/bc200556n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee D.; Baines M. G. Immunofluorescence Using Dichlorotriazinylaminofluorescein (DTAF) I. Preparation and Fractionation of Labelled IgG. J. Immunol. Methods 1976, 13 (3), 305–320. 10.1016/0022-1759(76)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M. J.; Oliveira B. L.; Martínez-Sáez N.; Guerreiro A.; Cal P. M. S. D.; Bertoldo J.; Maneiro M.; Perkins E.; Howard J.; Deery M. J.; Chalker J. M.; Corzana F.; Jiménez-Osés G.; Bernardes G. J. L. Chemo- and Regioselective Lysine Modification on Native Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (11), 4004–4017. 10.1021/jacs.7b12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.; Kawai Y.; Kitamoto N.; Osawa T.; Kato Y. Covalent Modification of Lysine Residues by Allyl Isothiocyanate in Physiological Conditions: Plausible Transformation of Isothiocyanate from Thiol to Amine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22 (3), 536–542. 10.1021/tx8003906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cal P. M. S. D.; Vicente J. B.; Pires E.; Coelho A. v; Veiros L. F.; Cordeiro C.; Gois P. M. P. Iminoboronates: A New Strategy for Reversible Protein Modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (24), 10299–10305. 10.1021/ja303436y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel C.; Kasper M.-A.; Stieger C. E.; Hackenberger C. P. R.; Christmann M. Protein Modification of Lysine with 2-(2-Styrylcyclopropyl)ethanal. Org. Lett. 2019, 21 (24), 10043–10047. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diethelm S.; Schafroth M. A.; Carreira E. M. Amine-Selective Bioconjugation Using Arene Diazonium Salts. Org. Lett. 2014, 16 (15), 3908–3911. 10.1021/ol5016509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. O.-Y.; Ho C.-M.; Chong H.-C.; Leung Y.-C.; Huang J.-S.; Wong M.-K.; Che C.-M. Modification of N-Terminal α-Amino Groups of Peptides and Proteins Using Ketenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (5), 2589–2598. 10.1021/ja208009r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj M.; Wu H.; Blosser S. L.; Vittoria M. A.; Arora P. S. Aldehyde Capture Ligation for Synthesis of Native Peptide Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (21), 6932–6940. 10.1021/jacs.5b03538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adusumalli S. R.; Rawale D. G.; Rai V. Aldehydes Can Switch the Chemoselectivity of Electrophiles in Protein Labeling. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16 (48), 9377–9381. 10.1039/C8OB02897D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singudas R.; Adusumalli S. R.; Joshi P. N.; Rai V. A Phthalimidation Protocol That Follows Protein Defined Parameters. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (3), 473–476. 10.1039/C4CC08503E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata J.; Krishnamoorthy L.; Gonzalez M. A.; Xiao T.; Iovan D. A.; Toste F. D.; Miller E. W.; Chang C. J. An Activity-Based Methionine Bioconjugation Approach To Developing Proximity-Activated Imaging Reporters. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6 (1), 32–40. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b01038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.; Yang X.; Jia S.; Weeks A. M.; Hornsby M.; Lee P. S.; Nichiporuk R. v; Iavarone A. T.; Wells J. A.; Toste F. D.; Chang C. J. Redox-Based Reagents for Chemoselective Methionine Bioconjugation. Science 2017, 355 (6325), 597–602. 10.1126/science.aal3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. T.; Nelson J. E.; Suero M. G.; Gaunt M. J. A Protein Functionalization Platform Based on Selective Reactions at Methionine Residues. Nature 2018, 562 (7728), 563–568. 10.1038/s41586-018-0608-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki Y.; Ishiyama T.; Sasaki D.; Abe J.; Sohma Y.; Oisaki K.; Kanai M. Transition Metal-Free Tryptophan-Selective Bioconjugation of Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (34), 10798–10801. 10.1021/jacs.6b06692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rizquez C.; Abian O.; Palomo J. M. Site-Selective Modification of Tryptophan and Protein Tryptophan Residues through PdNP Bionanohybrid-Catalysed C–H Activation in Aqueous Media. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (86), 12928–12931. 10.1039/C9CC06971B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi N. S.; Whitaker L. R.; Francis M. B. A Three-Component Mannich-Type Reaction for Selective Tyrosine Bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (49), 15942–15943. 10.1021/ja0439017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.-M.; Minakawa M.; Ueno L.; Tanaka F. Synthesis and Evaluation of a Cyclic Imine Derivative Conjugated to a Fluorescent Molecule for Labeling of Proteins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19 (4), 1210–1213. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban H.; Gavrilyuk J.; Barbas C. F. I. I. I. Tyrosine Bioconjugation through Aqueous Ene-Type Reactions: A Click-Like Reaction for Tyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (5), 1523–1525. 10.1021/ja909062q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban H.; Nagano M.; Gavrilyuk J.; Hakamata W.; Inokuma T.; Barbas C. F. I. I. I. Facile and Stabile Linkages through Tyrosine: Bioconjugation Strategies with the Tyrosine-Click Reaction. Bioconjugate Chem. 2013, 24 (4), 520–532. 10.1021/bc300665t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilyuk J.; Ban H.; Nagano M.; Hakamata W.; Barbas C. F. I. I. I. Formylbenzene Diazonium Hexafluorophosphate Reagent for Tyrosine-Selective Modification of Proteins and the Introduction of a Bioorthogonal Aldehyde. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23 (12), 2321–2328. 10.1021/bc300410p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S.; Matsumura M.; Kadonosono T.; Abe S.; Ueno T.; Ueda H.; Nakamura H. Site-Selective Protein Chemical Modification of Exposed Tyrosine Residues Using Tyrosine Click Reaction. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31 (5), 1417–1424. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.0c00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S.; Nakamura K.; Nakamura H. Tyrosine-Specific Chemical Modification with in Situ Hemin-Activated Luminol Derivatives. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10 (11), 2633–2640. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Heim A.; Riether D.; Yee D.; Milgrom Y.; Gawinowicz M. A.; Sames D. Reactivity of Functional Groups on the Protein Surface: Development of Epoxide Probes for Protein Labeling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125 (27), 8130–8133. 10.1021/ja034287m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka Y.; Tsutsumi H.; Kasagi N.; Nakata E.; Hamachi I. One-Pot and Sequential Organic Chemistry on an Enzyme Surface to Tether a Fluorescent Probe at the Proximity of the Active Site with Restoring Enzyme Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (10), 3273–3280. 10.1021/ja057926x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi H.; Miyagawa M.; Koshi Y.; Takaoka Y.; Tsukiji S.; Hamachi I. Affinity-Labeling-Based Introduction of a Reactive Handle for Natural Protein Modification. Chem. Asian J. 2008, 3 (7), 1134–1139. 10.1002/asia.200800057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiji S.; Miyagawa M.; Takaoka Y.; Tamura T.; Hamachi I. Ligand-Directed Tosyl Chemistry for Protein Labeling in Vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5 (5), 341–343. 10.1038/nchembio.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima S. H.; Yasui R.; Miki T.; Ojida A.; Hamachi I. Ligand-Directed Acyl Imidazole Chemistry for Labeling of Membrane-Bound Proteins on Live Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (9), 3961–3964. 10.1021/ja2108855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S.; Nakamura H. Ligand-Directed Selective Protein Modification Based on Local Single-Electron-Transfer Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (33), 8681–8684. 10.1002/anie.201303831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T.; Asanuma M.; Nakanishi S.; Saito Y.; Okazaki M.; Dodo K.; Sodeoka M. Turn-ON Fluorescent Affinity Labeling Using a Small Bifunctional O-Nitrobenzoxadiazole Unit. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5 (3), 1021–1029. 10.1039/C3SC52704B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse J.; Swier L. J. Y. M.; Oudshoorn R. C.; Médard G.; Kuster B.; Slotboom D. J.; Witte M. D. Targeted Diazotransfer Reagents Enable Selective Modification of Proteins with Azides. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28 (4), 913–917. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilamari M.; Kalra N.; Shukla S.; Rai V. Single-Site Labeling of Lysine in Proteins through a Metal-Free Multicomponent Approach. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (53), 7302–7305. 10.1039/C8CC03311K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu X.; Li B.; Liu H.-Y.; Sun X.; Yang X.; He G.; Zhou C.; Xuan W.; Liu S.-L.; Chen G. Bioconjugation via Hetero-Selective Clamping of Two Different Amines with ortho-Phthalaldehyde. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (2), e202212199. 10.1002/anie.202212199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilamari M.; Purushottam L.; Rai V. Site-Selective Labeling of Native Proteins by a Multicomponent Approach. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23 (16), 3819–3823. 10.1002/chem.201605938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim Y. E.; Nwajiobi O.; Mahesh S.; Cohen R. D.; Reibarkh M. Y.; Raj M. Secondary Amine Selective Petasis (SASP) Bioconjugation. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (1), 53–61. 10.1039/C9SC04697F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Disotuar M. M.; Xiong X.; Wang Y.; Chou D. H.-C. Selective N-Terminal Functionalization of Native Peptides and Proteins. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8 (4), 2717–2722. 10.1039/C6SC04744K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper M.-A.; Stengl A.; Ochtrop P.; Gerlach M.; Stoschek T.; Schumacher D.; Helma J.; Penkert M.; Krause E.; Leonhardt H.; Hackenberger C. P. R. Ethynylphosphonamidates for the Rapid and Cysteine-Selective Generation of Efficacious Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (34), 11631–11636. 10.1002/anie.201904193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S. J.; Omarjee S.; Galloway W. R. J. D.; Kwan T. T.-L.; Sore H. F.; Parker J. S.; Hyvönen M.; Carroll J. S.; Spring D. R. A General Approach for the Site-Selective Modification of Native Proteins, Enabling the Generation of Stable and Functional Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10 (3), 694–700. 10.1039/C8SC04645J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. P.; Smith A. B. Peptide/Protein Stapling and Unstapling: Introduction of s-Tetrazine, Photochemical Release, and Regeneration of the Peptide/Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (12), 4034–4037. 10.1021/ja512880g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Riegger A.; Lamla M.; Wiese S.; Oeckl P.; Otto M.; Wu Y.; Fischer S.; Barth H.; Kuan S. L.; Weil T. Water-Soluble Allyl Sulfones for Dual Site-Specific Labelling of Proteins and Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (5), 3234–3239. 10.1039/C6SC00005C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L.; Raabe M.; Zegota M. M.; Nogueira J. C. F.; Chudasama V.; Kuan S. L.; Weil T. Site-Selective Protein Modification via Disulfide Rebridging for Fast Tetrazine/Trans-Cyclooctene Bioconjugation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18 (6), 1140–1147. 10.1039/C9OB02687H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaunak S.; Godwin A.; Choi J.-W.; Balan S.; Pedone E.; Vijayarangam D.; Heidelberger S.; Teo I.; Zloh M.; Brocchini S. Site-Specific PEGylation of Native Disulfide Bonds in Therapeutic Proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2 (6), 312–313. 10.1038/nchembio786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruani A.; Smith M. E. B.; Miranda E.; Chester K. A.; Chudasama V.; Caddick S. A Plug-and-Play Approach to Antibody-Based Therapeutics via a Chemoselective Dual Click Strategy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6 (1), 6645. 10.1038/ncomms7645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Ye F.; Luo X.; Liu X.; Zhao J.; Wang S.; Zhou Q.; Chen G.; Wang P. Histidine-Specific Peptide Modification via Visible-Light-Promoted C–H Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (45), 18230–18237. 10.1021/jacs.9b09127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower S. J.; Hetcher W. J.; Myers T. E.; Kuehl N. J.; Taylor M. T. Selective Modification of Tryptophan Residues in Peptides and Proteins Using a Biomimetic Electron Transfer Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (20), 9112–9118. 10.1021/jacs.0c03039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adusumalli S. R.; Rawale D. G.; Singh U.; Tripathi P.; Paul R.; Kalra N.; Mishra R. K.; Shukla S.; Rai V. Single-Site Labeling of Native Proteins Enabled by a Chemoselective and Site-Selective Chemical Technology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (44), 15114–15123. 10.1021/jacs.8b10490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adusumalli S. R.; Rawale D. G.; Thakur K.; Purushottam L.; Reddy N. C.; Kalra N.; Shukla S.; Rai V. Chemoselective and Site-Selective Lysine-Directed Lysine Modification Enables Single-Site Labeling of Native Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (26), 10332–10336. 10.1002/anie.202000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Märcher A.; Palmfeldt J.; Nisavic M.; Gothelf K. V. A Reagent for Amine-Directed Conjugation to IgG1 Antibodies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (12), 6539–6544. 10.1002/anie.202013911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen R. A.; Märcher A.; Gothelf K. V. One-Step Conversion of NHS Esters to Reagents for Site-Directed Labeling of IgG Antibodies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022, 33 (10), 1811–1817. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu T.; Chilamari M.; Rai V. Protein Inspired Chemically Orthogonal Imines for Linchpin Directed Precise and Modular Labeling of Lysine in Proteins. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58 (11), 1768–1771. 10.1039/D1CC05559C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawale D. G.; Thakur K.; Sreekumar P.; Sajeev T. K.; Ramesh A.; Adusumalli S. R.; Mishra R. K.; Rai V. Linchpins Empower Promiscuous Electrophiles to Enable Site-Selective Modification of Histidine and Aspartic Acid in Proteins. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (19), 6732–6736. 10.1039/D1SC00335F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy N. C.; Molla R.; Joshi P. N.; Sajeev T. K.; Basu I.; Kawadkar J.; Kalra N.; Mishra R. K.; Chakrabarty S.; Shukla S.; Rai V. Traceless Cysteine-Linchpin Enables Precision Engineering of Lysine in Native Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6038. 10.1038/s41467-022-33772-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B. K.; Loveridge C. J.; Thyssen S.; Wørmer G. J.; Nielsen A. D.; Palmfeldt J.; Johannsen M.; Poulsen T. B. STEFs: Activated Vinylogous Protein-Reactive Electrophiles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (11), 3533–3537. 10.1002/anie.201814073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Hu Q. L.; Song Z.; Chan A. S. C.; Xiong X. F. Cleavable Cys Labeling Directed Lys Site-Selective Stapling and Single-Site Modification. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 65 (7), 1356–1361. 10.1007/s11426-022-1252-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur K.; Sajeev T. K.; Singh S. K.; Ragendu V.; Rawale D. G.; Adusumalli S. R.; Kalra N.; Shukla S.; Mishra R. K.; Rai V. Human Behavior-Inspired Linchpin-Directed Catalysis for Traceless Precision Labeling of Lysine in Native Proteins. Bioconjugate Chem. 2022, 33 (12), 2370–2380. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adak A. K.; Huang K. T.; Liao C. Y.; Lee Y. J.; Kuo W. H.; Huo Y. R.; Li P. J.; Chen Y. J.; Chen B. S.; Chen Y. J.; Chu Hwang K.; Wayne Chang W. S.; Lin C. C. Investigating a Boronate-Affinity-Guided Acylation Reaction for Labelling Native Antibodies. Chem. - Eur. J. 2022, 28 (17), e202104178. 10.1002/chem.202104178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B. X.; Kim D. K.; Bloom S.; Huang R. Y.-C.; Qiao J. X.; Ewing W. R.; Oblinsky D. G.; Scholes G. D.; MacMillan D. W. C. Site-Selective Tyrosine Bioconjugation via Photoredox Catalysis for Native-to-Bioorthogonal Protein Transformation. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13 (9), 902–908. 10.1038/s41557-021-00733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson P. E.; Muir T. W.; Clark-Lewis I.; Kent S. B. H. Synthesis of Proteins by Native Chemical Ligation. Science 1994, 266 (5186), 776–779. 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agouridas V.; el Mahdi O.; Diemer V.; Cargoët M.; Monbaliu J.-C. M.; Melnyk O. Native Chemical Ligation and Extended Methods: Mechanisms, Catalysis, Scope, and Limitations. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (12), 7328–7443. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent S. B. H. Total Chemical Synthesis of Proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38 (2), 338–351. 10.1039/B700141J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casi G.; Huguenin-Dezot N.; Zuberbühler K.; Scheuermann J.; Neri D. Site-Specific Traceless Coupling of Potent Cytotoxic Drugs to Recombinant Antibodies for Pharmacodelivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (13), 5887–5892. 10.1021/ja211589m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay A.; Cambray S.; Gao J. Fast and Selective Labeling of N-Terminal Cysteines at Neutral pH via Thiazolidino Boronate Formation. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (7), 4589–4593. 10.1039/C6SC00172F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustino H.; Silva M. J. S. A.; Veiros L. F.; Bernardes G. J. L.; Gois P. M. P. Iminoboronates Are Efficient Intermediates for Selective, Rapid and Reversible N-Terminal Cysteine Functionalisation. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7 (8), 5052–5058. 10.1039/C6SC01520D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.; Wang W.; Gao J. Fast and Stable N-Terminal Cysteine Modification through Thiazolidino Boronate Mediated Acyl Transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (34), 14246–14250. 10.1002/anie.202000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. I.; Munch H. K.; Moore T.; Francis M. B. One-Step Site-Specific Modification of Native Proteins with 2-Pyridinecarboxyaldehydes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11 (5), 326–331. 10.1038/nchembio.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoda A.; Inoue N.; Sumiyoshi E.; Hayashi T. Triazolecarbaldehyde Reagents for One-Step N-Terminal Protein Modification. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21 (9), 1274–1278. 10.1002/cbic.201900692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore J. M.; Scheck R. A.; Esser-Kahn A. P.; Joshi N. S.; Francis M. B. N-Terminal Protein Modification through a Biomimetic Transamination Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (32), 5307–5311. 10.1002/anie.200600368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushottam L.; Adusumalli S. R.; Singh U.; Unnikrishnan V. B.; Rawale D. G.; Gujrati M.; Mishra R. K.; Rai V. Single-Site Glycine-Specific Labeling of Proteins. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2539. 10.1038/s41467-019-10503-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Li X.; Wang Y.; Mao X.; Wang X. Post-Translational Site-Specific Protein Azidolation with an Azido Pyridoxal Derivative. Chem. Commu. 2022, 58 (53), 7408–7411. 10.1039/D2CC03051A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]