Abstract

Background:

Piperacillin/tazobactam is one of the most frequently used antimicrobials in older adults.

Introduction:

Using an opportunistic study design we evaluated the pharmacokinetics (PK) of piperacillin/tazobactam as a probe drug to evaluate changes in antibacterial drug exposure and dosing requirements, including in older adults.

Methods:

A total of 121 adult patients were included. The population PK models that best characterized the observed plasma concentrations of piperacillin and tazobactam were one-compartment structural models with zero-order input and linear elimination.

Results:

Among all potential covariates, estimated creatinine clearance had the most substantial impact on the elimination clearance for both piperacillin and tazobactam. After accounting for renal function and body size, there was no remaining impact of frailty on the PK of piperacillin and tazobactam. Monte Carlo simulations indicated that renal function had a greater impact on the therapeutic target attainment than age, although these covariates were highly correlated. Frailty, using the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale, was assessed in 60 patients who were ≥65 years of age.

Conclusion:

The simulations suggested that adults ≤50 years of age infected with organisms with higher minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) may benefit from continuous piperacillin/tazobactam infusions (12 g/day of piperacillin component) or extended infusions of 4 g every 8 hours. However, for a target of 50% fT>MIC, dosing based on renal function is generally preferable to dosing by age, and simulations suggested that patients with creatinine clearance ≥120 mL/min may benefit from infusions of 4 g every 8 hours for organisms with higher MICs.

Keywords: pharmacokinetics, piperacillin/tazobactam, opportunistic sampling, older adults

1. Introduction

Serious bacterial infections in older persons are common and often deadly. The mainstay of therapy for these infections is systemic antibiotics. Despite their common use in this population, little is known about the pharmacokinetics (PK) of most intravenously-administered antibiotics in older patients (defined as 65 years of age and older). This is problematic because renal excretion and hepatic metabolism of drugs often decline with aging, thereby decreasing drug clearance (CL) and increasing systemic exposure to an administered dose [1, 2]. For example, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines by ~14 ml/min/decade in men and 7.1 ml/min/decade in women after 35 years of age, resulting in reduced clearance for renally-eliminated drugs [3]. Moreover, antibacterial pharmacodynamic (PD) target concentrations may be different in older adults, due to impaired host immunity and changes in body composition [4]. As a result of these PK and PD changes, older patients are at high risk for treatment failure or toxicity. Therefore, PK/PD studies in older adults are needed to guide appropriate dosing of antimicrobials and optimize clinical outcomes.

As a proof of concept, we evaluated the PK of piperacillin/tazobactam to evaluate changes in antibacterial drug exposure and required dosing across different stages of the adult lifespan using an opportunistic study design. Piperacillin/tazobactam is used in adults as first-line therapy for health care-associated pneumonia and most gram-negative infections [5]. Piperacillin elimination is primarily by renal filtration and tubular secretion, with up to 68% of the dose appearing as unchanged drug in urine. Up to 80% of tazobactam is excreted in urine as unchanged drug. Both piperacillin and tazobactam undergo hepatic biotransformation, with significant liver injury increasing the half-life of piperacillin by 25% and tazobactam by 18%, respectively [6]. Additionally, piperacillin may have non-linear drug disposition [7]. Due to expected changes in older adults, a dedicated PK study for piperacillin/tazobactam is indicated to optimize dosing.

The primary objective of this study was to use a population PK modeling approach to quantify how the systemic clearance of piperacillin/tazobactam changes with increasing age. The exploratory objective was to evaluate whether frailty, after considering the impact of renal function and age, is associated with a change in systemic clearance of piperacillin/tazobactam in older adults.

2. Results

2.1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 121 patients receiving piperacillin/tazobactam per standard of care were enrolled (119 unique patients with 2 patients re-enrolled at different time points). Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The study patients were predominantly male (64%) and white (88%). Mean creatinine clearance (estimated using the Cockcroft-Gault method) was 86.9 mL/min (standard deviation 62), mean weight was 92.2 kg (standard deviation 29.0) (Table 1), and median frailty score varied by age range (Table 2). Frailty evaluations were available for all 60 patients who were ≥65 years of age (Table 2) [8]. Fifteen patients (25%) had a frailty score of 5 (mild frailty) and 15 patients (25%) had scores of 6 (moderate frailty) or 7 (severe frailty).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients receiving piperacillin/tazobactam

| Demographic | n=121 |

|---|---|

| Age in years* | 62.8 ± 18.9 (21, 96) |

| 18-50 | 40 (33.0) |

| 51-64 | 21 (17.4) |

| 65-74 | 20 (16.5) |

| 75-84 | 20 (16.5) |

| ≥85 | 20 (16.5) |

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Male | 77 (64.0) |

| Female | 44 (36.0) |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | |

| Not Hispanic | 116 (96.0) |

| Hispanic | 4 (3.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (<1.0) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| White | 107 (88.0) |

| Black or African American | 12 (10.0) |

| Multiracial | 1 (<1.0) |

| Weight (kg)* | 92.2 ± 29.0 |

| Height (cm)* | 171.3 ± 10.7 |

| CrCl by age | |

| 18-50 | 131.4 (79.0) |

| 51-64 | 88.4 (45.0) |

| 65-74 | 68.4 (42.0) |

| 75-84 | 60.86 (26.0) |

| 85+ | 45.5 (23.0) |

| Weight by age | |

| 18-50 | 104.5 (37.0) |

| 51-64 | 89.6 (27.0) |

| 65-74 | 95.2 (20.0) |

| 75-84 | 84.8 (21.0) |

| 85+ | 75.9 (16.0) |

BMI, body mass index; CrCl, creatinine clearance; SD, standard deviation

Data are mean ± SD.

Table 2.

Distribution of frailty scores on the CSHA Clinical Frailty Scale for patients ≥65 years of age

| Age range in years | n | CSHA Clinical Frailty Scale score, median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| 65-74 | 20 | 4 (2-7) |

| 75-84 | 20 | 4 (1-7) |

| ≥85 | 20 | 6 (2-7) |

CSHA, Canadian Study of Health and Aging

Almost all doses were 3000 mg piperacillin with 375 mg tazobactam. There were two patients for whom dosing was different; one patient who received two doses of 2000/250 mg in (no samples collected following those infusions); and one patient who received several doses of 4000/500 mg (3 blood sample collected). Overall, 96% of the piperacillin/tazobactam doses were administered as ≥4-hour infusions. Optimal blood sampling windows were determined a priori and are noted in Supplemental Table 1. While most patients had samples collected within these optimal times, samples collected outside of these windows were accepted with exact collection time recorded. In total, 365 plasma samples were collected from 119 patients, an average 3.1 samples per patient. Of these, 358 samples had measurable piperacillin concentrations and 7 were below the quantification limit; for tazobactam, 351 samples had measurable concentrations and 14 were below the quantification limit.

2.2. Population PK Model Development and Evaluation

Based on standard population PK model diagnostics (prediction corrected visual predictive checks, normalized prediction distribution error, objective function value, feasibility of parameter estimates, and goodness of fit plots) the population PK models that best portrayed the observed plasma concentrations of piperacillin and tazobactam were one-compartment structural models with zero-order input and linear elimination. Compared to the M3 method for samples beneath the quantifiable limit (BQL), the best model performance was obtained by excluding BQL samples. The residual error models were best characterized using combined additive and proportional error. Among all potential covariates, estimated creatinine clearance had the most substantial impact on the elimination clearance for both piperacillin and tazobactam, and decreased the variance in inter-individual variability (IIV) on piperacillin clearance by 51% and tazobactam clearance by 27%. In agreement with the known major route of elimination of these drugs, an increase in creatinine clearance was associated with increased renal clearance for both piperacillin and tazobactam. Total body weight was identified to have an impact on the volume of distribution for both drugs (decrease in piperacillin IIV coefficient of variation by 24% and tazobactam by 20%) and nonrenal clearance for tazobactam. Following the incorporation of renal function and body size as covariates, there were no remaining trends between the demographic characteristics of age and sex and the PK parameters. After inclusion of these covariate effects into the model, frailty could not explain additional variability in PK. Final population PK parameter estimates for piperacillin and tazobactam are in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Covariate selection steps are noted in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks suggested that the final model characterized the central tendency (median) and variability of the data well, with the majority of observed concentrations falling within the 80% prediction interval (Figure 1 for piperacillin and Figure 2 for tazobactam). Additional diagnostic plots for the final piperacillin and tazobactam models are in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Final population PK parameter estimates for piperacillin

| Parameter | Unit | Population estimate |

Standard error |

IIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR | L/h per 69 mL/min CrCl | 4.09 | 16% | 47% |

| CLNR | L/h | 2.44 | 23% | |

| V | L per 89 kg WT | 31.8 | 11% | 25% |

| Proportional error | - | 35.8% | - | - |

| Additive Error | mg/L | 0.0488 | - | - |

CL, clearance; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CLNR, non-renal clearance; CLR, renal clearance; IIV, inter-individual variability; PK, pharmacokinetics; V, volume; WT, weight

Eta shrinkage was 8.8% for total clearance (CLR+CLNR) and 48% for V. The correlation between eta values for total clearance and volume was 52%.

Table 4.

Final population PK parameter estimates for tazobactam

| Parameter | Unit | Population estimate |

Standard error |

IIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR | L/h per 69 mL/min CrCl | 5.18 | 12% | 47% |

| CLNR | L/h per 89 kg WT0.75 | 1.14 | 46% | |

| V | L per 89 kg WT | 40.3 | 14% | 21% |

| Proportional error | - | 30% | - | - |

| Additive error | mg/L | 0.562 | - | - |

CL, clearance; CLNR, non-renal clearance; CLR, renal clearance; CrCl, creatinine clearance; IIV, inter-individual variability; PK, pharmacokinetics; V, volume; WT, weight

Eta shrinkage was 10% for total clearance (CLR+CLNR) and 61% for V. The correlation between eta values for total clearance and volume was 35%.

Figure 1. Prediction-corrected visual predictive check for the final piperacillin model.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check for the final piperacillin model for all patients and all times past start of infusion. Note: Data were very sparse for times past start of infusion >8 hours.

Figure 2. Prediction-corrected visual predictive check for the final tazobactam model.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check for the final tazobactam model for all patients and all times past start of infusion. Note: Data were very sparse for times past start of infusion >8 hours.

2.3. Dosing Simulations

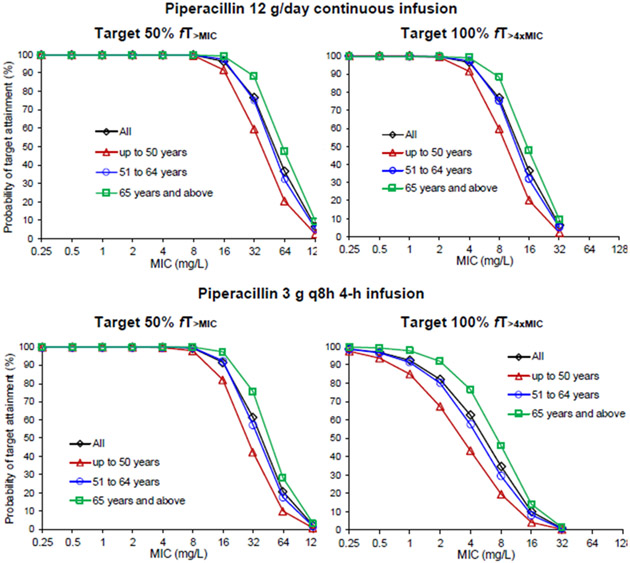

Monte Carlo simulations were used to evaluate the probability of target attainment (PTA) using various dosing regimens of piperacillin per day with three targets: 1) the target of unbound piperacillin concentrations above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for 50% of the dosing interval at steady-state (50% fT>MIC); 2) unbound piperacillin concentrations above the MIC for 100% of the dosing interval at steady-state (100% fT>MIC); and 3) unbound piperacillin concentrations above four times the MIC for 100% of the dosing interval at steady-state (100% fT>4xMIC). We evaluated target attainment stratified by age, and separately, by renal function.

Results of the dosing simulations for piperacillin stratified by age are illustrated in Figure 3. In adults ≤50 years of age, piperacillin 3 g every 8 hours (q8h) as a 4-hour infusion is predicted to have ≥90% attainment of the 50% fT>MIC target for organisms with an MIC up to 8 mg/L. Conversely, adults older than 50 years are predicted to reliably obtain target attainment for organisms with an MIC up to 16 mg/L. Dosing simulations suggested that both a continuous infusion (12 g/day) (Figure 3) and 4 g q8h as 4-hour infusions (Supplemental Table 4) are predicted to achieve the target of 50% fT>MIC for organisms up to 16 mg/L in adults ≤50 years of age. The only dosage regimen that provides for a breakpoint of 16 mg/L across all age groups for the PK/PD target 100% fT>MIC was the 12 g/day continuous infusion. None of the dosage regimens cover 16 mg/L for the most aggressive PK/PD target (100% fT>4xMIC).

Figure 3. Probability of target attainment for piperacillin by age group and dosing regimen.

Probability of target attainment for piperacillin by age group and dosing regimen (target 50% fT>MIC and 100% fT>4xMIC of piperacillin 12 g/day continuous infusion and 3 g q8h 4-hour infusion).

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration

Dosing simulations for piperacillin stratified by renal function (i.e., estimated creatinine clearance) are illustrated in Figure 4. In general, the differences in target attainment vs. MIC between renal function groups were larger than those between age groups, suggesting renal function has a greater impact on the PTA than age. Only with a piperacillin regimen of 4 g every 8 hours as a 4-hour infusion, are patients with a creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≥120 mL/min predicted to achieve the 50% fT>MIC target for organisms with an MIC of 16 mg/L (Supplemental Table 5). However, >90% of patients with CrCl <120 mL/min achieved the 50% fT>MIC target for all dosage regimens.

Figure 4. Comparison of piperacillin PTA between different renal function groups.

Comparison of piperacillin PTA between different renal function groups: less than 60 mL/min, 60 to 119 mL/min, and 120 mL/min and above, for two different dosage regimens.

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; PTA, probability of target attainment

For the intermediate PK/PD target of 100% fT>MIC, patients with CrCl ≥120 mL/min will only reach a breakpoint MIC of 8 mg/L, with 12g/day as a continuous infusion; no dosage regimens were predicted to reach a breakpoint MIC of 16 mg/L (data not shown). Conversely, 12g/day as a continuous infusion will achieve an MIC of 16 mg/L in those with CrCl 60–119 mL/min, and 32 mg/L in those with CrCl <60 mL/min.

For the most aggressive PK/PD target of 100% fT>4xMIC patients, the highest breakpoint MIC with ≥90% PK/PD target attainment for the 12g/day continuous infusion was 2 mg/L for those with a CrCl ≥120 mL/min; 4 mg/L for those with CrCl 60 –119 mL/min; and 8 mg/L for those with CrCl <60 mL/min.

In a sensitivity analysis, Monte Carlo simulations were performed for tazobactam, simulating from the whole study population and using a protein binding of 30% for tazobactam. The PTA was evaluated at the targets of 85% fT>2 mg/L (2 log10 CFU/mL bacterial killing of high-level β-lactamase-producing strains) and 85% fT>0.25 mg/L (2 log10 CFU/mL bacterial killing of low-level β-lactamase-producing strains). The targets are based on studies by Nicasio et al. [9] that used isogenic CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli strains. Subsequently, the joint PTA was calculated based on achievement of the piperacillin PK/PD target and tazobactam PK/PD target in each simulated patient.

The Monte Carlo simulations for tazobactam indicated, for continuous infusion treatment with 12g/1.5g piperacillin/tazobactam, a PTA of 95% at the 85% fT>2 mg/L target and 100% at the 85% fT>0.25 mg/L target. Therefore, all joint PTA results for the continuous infusion were very similar to the PTA results when only target attainment of piperacillin was considered. For prolonged infusion treatment with 3g/0.375g piperacillin/tazobactam every 8h, the tazobactam PTA was 74% at the 85% fT>2 mg/L target and 99% at the 85% fT>0.25 mg/L target. For the prolonged infusions and piperacillin 50% fT>MIC and tazobactam 85% fT>2 mg/L targets, the joint PTAs were very similar to those for piperacillin alone up to an MIC of 32 mg/L. For the piperacillin 100% fT>4xMIC and tazobactam 85% fT>2 mg/L targets, the joint PTAs were very similar to those for piperacillin alone up to an MIC of 4 mg/L. At lower MICs the maximum PTA plateaued at 74% (driven by tazobactam target attainment), but this is only relevant if strains with relatively low MICs can still be high-level β-lactamase producers. For prolonged infusions and the tazobactam 85% fT>0.25 mg/L target, the joint PTAs were very similar to the PTAs for piperacillin alone, regardless of the piperacillin target.

3. Discussion

We conducted a population PK analysis to evaluate the factors (e.g., age, renal function, frailty) that may impact the disposition of piperacillin/tazobactam across the adult lifespan. While this design approach has been used before in children [10-12], to our knowledge, it is the first time that this approach has been used in a large sample size of older adults [13, 14].

Dosing simulations suggested that adults ≤50 years of age do not reliably reach even the 50% fT>MIC target for “susceptible increased exposure” organisms with the highest epidemiologic cutoff value (ECOFF) of 16 mg/l, which applies to several organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Accordingly, adults ≤50 years of age may benefit from continuous piperacillin infusions (12 g/day) or extended infusions of 4 g every 8 hours given as 4-hour infusions when encountering organisms with an MIC breakpoint of 16 mg/L. Conversely, all age groups are predicted to reliably achieve the 50% fT>MIC target at standard dosing of piperacillin 3 g every 8 hours as 4-h infusions for organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, which have an ECOFF of 8 mg/L. Alternative dosing strategies to the conventional intermittent infusion regimen have also been suggested by other authors, due to a potentially higher clinical cure rate and lower mortality [15-18]. Yet notably, the Food and Drug Administration dosing recommendations do not address other non-traditional infusion methods [5].

Importantly, the only dosage regimen that provides for a breakpoint of 16 mg/L across all age groups for the PK/PD target 100% fT>MIC was the 12 g/day continuous infusion; this is of significance because some authors have suggested that higher PK/PD targets than the traditional 50% fT>MIC (e.g., fT>MIC of >61%) are associated with improved survival in patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia [19, 20]. Indeed when treating older adults with severe infections, the motto “start low and go slow” should be ignored, since using this approach risks under-dosing, especially in cases where resistant organisms, serious infections, and time-to-effective treatment is a significant contributor to outcome [21, 22]. Continuous infusions may have additional advantages in this population as the 12g/day as a continuous infusion also achieved an MIC of 16 mg/L in those with CrCl 60–119 mL/min, and 32 mg/L in those with CrCl <60 mL/min. However, renal function should be monitored closely and piperacillin/tazobactam dose should be adjusted if needed, since its nephrotoxicity has been reported in older adults [23].

Our covariate analysis suggested that differences in renal function had a substantially larger impact on clearance of the drug than did age, consistent with the known (renal) mechanism of piperacillin clearance [5]. Accordingly, age was not included as a covariate in the PK model. It is well established that creatinine clearance decreases with age, although there is large inter-individual variability in the degree of change in creatinine clearance with age [24, 25]; as a result, it is not surprising that creatinine clearance would perform better than age. Additionally, we observed a greater impact of renal function on PK/PD target attainment compared to age. Therefore, dosing based on renal function may be preferred instead of dosing based on age. We observed that in patients with CrCl <120 mL/min, and the PK/PD target of 50% fT>MIC, all evaluated regimens cover the ECOFF of 16 mg/L.

An exploratory objective of our study was to evaluate whether frailty is associated with a change in systemic clearance of piperacillin/tazobactam in the elderly. Frailty scores were limited to patients 65 years and older because the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) Clinical Frailty Scale is only validated in older adults (Supplemental Table 6). After accounting for renal function and body weight, there was no remaining impact of frailty on the PK of piperacillin and tazobactam. These findings should be viewed as preliminary, due to the small sample size of patients who were frail with a score of 5, 6, or 7. Future research that examines frailty and PK of antibiotics should include larger sample sizes and robust measures of frailty, as it is increasingly believed that frailty in the setting of multiple comorbidities and severe deconditioning plays an important role in predicting a patient’s drug metabolism [1, 26].

A key innovation of the study was using an opportunistic PK study design in a vulnerable population that overcame the challenges in older adults of high blood volume requirements for intense PK sampling, low consent rates in trials, and comorbid conditions preventing enrollment in clinical studies [27]. Limitations of our study included lack of microbiologic correlation, an average of 3.1 samples collected per patient, which were fewer than the number targeted in the protocol and a low number of older adults with higher CSHA clinical frailty scores. Additionally, we did not simulate the impact of loading dosages on target attainment; and certain clinical situations (e.g., septic shock) may benefit from achieving rapid, therapeutic antimicrobial concentrations [28]. Using our PK model, future researchers could simulate the impact of loading doses and time to target attainment.

In summary, from a clinical perspective, dosing of piperacillin/tazobactam based on renal function is preferable to dosing by age or frailty status, especially since patients of the same age group can have different renal function or frailty status. Patients with CrCl ≥120 mL/min may require infusions of 4 g every 8 hours as 4-hour infusions for organisms with a breakpoint MIC of 16 mg/L) to reach even the 50% fT>MIC target.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

The design was an opportunistic population-based PK study among adult men and women ≥18 years old receiving piperacillin/tazobactam per standard of care at Duke University Medical Center and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. The primary outcome measure of the study was the total plasma concentrations of piperacillin/tazobactam. As an exploratory outcome measure, we quantified the effect of frailty (as measured by the pre-hospitalization CSHA Clinical Frailty Scale recorded at enrollment) on the PK of piperacillin/tazobactam [8]. Hospitalized adult patients who had an active medication order of piperacillin/tazobactam were identified and approached for potential study enrollment. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the respective study sites.

4.2. Patient/Population

Patients eligible to participate in this study had to meet all 4 inclusion criteria. Patients had to be: 1) receiving care at a participating hospital site; 2) receiving piperacillin/tazobactam per standard of care; 3) willing and able to provide written informed consent, or have a legally authorized representative willing to provide written informed consent; and 4) aged ≥18 years. Patients were not eligible if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, their physician believed the risks of participation outweighed the benefit, or they had a condition that would place them at unacceptable risk of injury or confound data interpretation. The group aged 18–50 years served as the standard adult group (enrollment target was 40) with the remaining age groups having each up to 20 patients (51–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years) aiming for a total of approximately 120 patients. We collected demographic and clinical characteristics, relevant concomitant medications, and CSHA Clinical Frailty Score. Patient participation was 14 days.

4.3. Drug Dosing and Sample Collection

Drug dosing was per standard of care and per primary treating physician. Target sampling time points for other than standard of care blood draws are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Although samples did not need to be drawn strictly per the specified target time points, the exactly sampling time is recorded and attempts were made to obtain samples as close as possible to the noted schedule. Blood sample collections were not performed from the same infusion line where antibiotics were administered. Blood samples for PK analysis were obtained from either a venipuncture at a different anatomic site or from a different catheter than the one used for antibiotic administration.

4.4. Analytical Methods

4.4.1. Analysis of plasma concentrations of piperacillin-tazobactam

Piperacillin and tazobactam were extracted from human plasma using acetonitrile containing piperacillin-d5 and dicloxacillin as internal standards. Extracts were analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS using positive ion multiple reaction monitoring. This method was validated over the range 100 to 50000 ng/mL for piperacillin and tazobactam and the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was 100 ng/mL using a 15 uL aliquot of human plasma. Piperacillin and tazobactam concentrations in human plasma were measured by a validated high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) assay with a range of 100–50,000 ng/mL for each analyte. The within-run accuracy was 81.1% (lower limit of quantitation) to 107.3% and the within-run precision (% coefficient of variation) was 0.9% to 2.8%. The range was extended to 400,000 ng/mL with validated dilutional linearity testing.

4.4.2. Samples below the lower limit of quantitation

Two methods were evaluated. These included excluding samples below the lower limit of quantitation and the Beal M3 method in NONMEM [29].

4.5. Population PK Analysis

Population PK analysis was conducted using nonlinear mixed effects modeling in NONMEM® Version 7.2 (ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD).

One- and two-compartment disposition models with linear, saturable, and parallel linear and saturable elimination were tested for piperacillin and tazobactam. The first-order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCE+I) algorithm was utilized for modeling. R scripts were utilized for generation of model evaluation plots using rStudio Version 1.1.463 (rStudio, Inc., Boston, MA).

4.6. Model Evaluation

For each model evaluated, NONMEM computed the minimum value of the objective function, a statistic that was equivalent to minus twice the log likelihood (-2LL). The log-likelihood ratio (-2LL or -2 log likelihood) was used for comparison of two nested (hierarchical) models, and Δ-2LL was the change in -2LL (i.e., the NONMEM objective function value) relative to the comparator or reference model. The best-fit model will display the lowest objective function value. A reduction in the objective function by more than the critical value of 3.84 units (Δdf =1 for one added degree of freedom, and α=0.05) represented a statistically significant improvement in model fit (chi-square distribution, p<0.05). Creatinine clearance, clinical laboratory values, total body weight, and estimated lean body weight can change over time; these measurements were incorporated as time-varying covariates, when possible. Since increasing age is correlated with physiological changes, the potential effect of age was evaluated following incorporation of weight or low birth weight, and CrCl.

The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to compare any two non-nested models, where the model with lower AIC was selected. AIC is defined as -2LL + 2p, where p is the number of parameters estimated in the model. The goodness-of-fit was evaluated graphically via standard diagnostic plots, including plots of observed versus individual (post-hoc) predicted drug concentrations, observed versus population predicted drug concentrations, and conditional weighted residuals versus time past start of infusion. The predictive performance was evaluated by the normalized prediction distribution error plotted versus time past start of infusion, normalized prediction distribution error plotted versus population predicted drug concentration, and prediction-corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPC, n=1000 simulated datasets) [30].

For the prediction-corrected visual predictive checks, the PK profiles were simulated for 1000 replicates of the study dataset for each of the competing models and respective drug. From these data, the median and nonparametric 80% prediction interval (10th to 90th percentiles), was calculated. These prediction interval lines were overlaid on the observed data. Whether the median and the prediction intervals mirrored the central tendency and the variability of the observed data for the respective model was evaluated. In addition to the whole study population, the prediction-corrected visual predictive checks were also conducted stratified by the most important covariates (renal function and demographics of interest [e.g., age]). Due to the sparse nature of the data, the prediction-corrected visual predictive checks were performed according to our published regression approach that negates the need for empirical bin selection [30].

Reductions in the unexplained IIV were evaluated as outlined in the Covariate Analysis section in the Supplemental Material. Eta-shrinkage was evaluated, with shrinkage values <30% considered desirable; however, the sparse sample collection in the current study hampered the ability to estimate the IIV at targeted shrinkage values, especially for volumes of distribution. The precision of the parameter estimates was evaluated for each candidate model through the standard errors as calculated within NONMEM. In addition to the statistical model selection criteria, the plausibility of the parameter estimates with respect to known physiology and pathophysiology was considered, given the sparse sampling in this study. The covariate analysis process is outlined in Supplemental Methods.

4.7. Dosing Simulations

Monte Carlo simulations were performed using the final PK model to evaluate the probability of therapeutic target attainment (PTA) for different dosage regimens of piperacillin by simulating at least 10,000 virtual patients for each combination of dosage regimen and patient population. The ECOFF is a measure of a drug MIC distribution that distinguishes between organisms without (wild type) and with expressed resistance mechanisms. Two dosing regimens which are currently used clinically were simulated including IIV (piperacillin: 3 g q8h as a 4-hour infusion, and 12 g/day as continuous infusion). Additionally, a regimen of 4 g piperacillin q8h as 4-hour infusion was simulated to enable comparison with the continuous infusion at the same daily dose. Inclusion of IIV enabled the evaluation of the expected concentration-time profiles across a patient population. Simulations were performed based on the whole study population and separately for different age and renal function groups.

With the Monte Carlo simulations estimating the probability of target attainment, the percentage of a patient population that is expected to achieve the relevant PK/PD target was calculated. The PK/PD index which best predicts bacterial killing and clinical outcomes for β-lactam antibiotics, including piperacillin, is the fT>MIC [31]. The fT>MIC is defined as the cumulative percentage of a 24-hour period during which the unbound drug concentration exceeds the MIC at steady-state PK conditions, or the corresponding percentage of a dosing interval [32]. Traditional targets required to maximize bacterial killing, fT>MIC values of 50% for penicillins (including piperacillin), have been reported and used in Monte Carlo simulations [33-37]. A more conservative target, requiring the unbound concentration of β-lactam antibiotics to remain above the MIC during the whole dosing interval (100% fT>MIC) is also commonly used [38, 39]. Additionally, retrospective clinical evaluations and other studies have suggested that even larger drug exposures (e.g., unbound concentrations of approximately 4× MIC for the entire dosing interval [100% fT>4×MIC]) may be required especially for resistance suppression. Accordingly, both the traditional and the higher PK/PD targets were included in the evaluation of the therapeutic target attainment for dosing regimens of the piperacillin component of piperacillin/tazobactam [40-42].

Unbound (free) concentrations at steady-state were simulated, using a protein binding of 30% for piperacillin [43]. A clinical breakpoint is a MIC (mg/L) that separates strains for which there is a high likelihood of treatment success using approved (or accepted as safe) dosing regimens from those strains where treatment is more likely to fail with the same regimens. The PK/PD breakpoint was defined as the highest MIC with a PTA of at least 90% for a given PK/PD targeted exposure, using an approved (or accepted as safe) dosing regimen. Published MIC distributions were considered in choosing the range of MICs for which the PTA was evaluated, including those by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), which are collated from worldwide sources.

In a sensitivity analysis, Monte Carlo simulations were performed for tazobactam, simulating from the whole study population and using a protein binding of 30% for tazobactam. The PTA was evaluated at the targets of 85% fT>2 mg/L (2 log10 CFU/mL bacterial killing of high-level β-lactamase-producing strains) and 85% fT>0.25 mg/L (2 log10 CFU/mL bacterial killing of low-level β-lactamase-producing strains). The targets are based on studies by Nicasio et al. [9] that used isogenic CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli strains. Subsequently the joint PTA was calculated based on achievement of the piperacillin PK/PD target and tazobactam PK/PD target in each simulated patient.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

In a large sample size of older adults, we conducted a population pharmacokinetic analysis to evaluate the factors (e.g., age, renal function, frailty) that may impact the disposition of piperacillin/tazobactam across the adult lifespan.

From a clinical perspective, dosing of piperacillin/tazobactam based on renal function is preferable to dosing by age or frailty status, especially since patients of the same age group can have different renal function or frailty status.

Patients with creatinine clearance ≥120 mL/min may require infusions of 4 g every 8 hours as 4-hour infusions for organisms with a breakpoint minimum inhibitory concentration of 16 mg/L to reach even the 50% fT>minimum inhibitory concentration target.

Sources of Funding

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), US Department of Health and Human Services, through Contract No. HHSN272201500002C (Emmes) and a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units (VTEU) award under Contract No. HHSN272201300017I (Duke University) and Contract No. HHSN2722013000201 (University of Iowa). This work was also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant number 5T32AI100851 to MHM). KES also received support from the National Institute on Aging, Duke Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, NIA P30AG028716. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. MCW receives support for research from the NIH [1U24-MD016258], National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [HHSN272201500006I, HHSN272201300017I, 1K24-AI143971], NICHD [HHSN275201000003I], U.S. Food and Drug Administration [5U18-FD006298], and industry for drug development in adults and children.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

SJB receives support from the National Institutes of Health, the US Food and Drug Administration, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Rheumatology Research Foundation’s Scientist Development Award, the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, Purdue Pharma, and consulting for UCB.

The remaining authors have no relevant disclosures.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained by patients or their legally authorized representative.

Ethics Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the respective study sites.

Consent for Publication

All authors have approved the final manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Marion Hemmersbach-Miller, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC USA; and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC USA.

Stephen J. Balevic, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC USA; Department of Pediatrics, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC USA; and Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology and Immunology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC USA.

Patricia L. Winokur, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA USA.

Cornelia B. Landersdorfer, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Kenan Gu, Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD USA.

Austin W. Chan, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC USA.

Michael Cohen-Wolkowiez, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC USA; and Department of Pediatrics, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC USA.

Thomas Conrad, The EMMES Company, LLC, Rockville, MD USA.

Guohua An, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA USA.

Carl M. J. Kirkpatrick, Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria, Australia.

Geeta K. Swamy, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Obstetrics Clinical Research, Duke University Medical System, Durham, NC USA.

Emmanuel B. Walter, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC USA; Department of Pediatrics, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC USA; and Duke Human Vaccine Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC USA.

Kenneth E. Schmader, Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC USA; and Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Durham, NC USA.

Data Availability

Data are to be made available as widely as possible, while safeguarding the privacy of participants, and protecting confidential and proprietary data.

References

- 1.Cusack BJ. 2004. Pharmacokinetics in older persons. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004;2:274–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangoni AA, Jackson SHD. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rule AD, Gussak HM, Pond GR, et al. Measured and estimated GFR in healthy potential kidney donors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:112–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson JM. Antimicrobial pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Piperacillin/tazobactam for injection, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA. FDA; web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/050684s88s89s90_050750s37s38s39lbl.pdf. Published 2015. Updated May 2017. Accessed July 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Zosyn® (piperacillin and tazobactam injection) in Galaxy® containers (PL 2040 plastic). FDA; web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/050750s015lbl.pdf. Updated February 2007. Accessed July 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felton TW, Hope WW, Lomaestro BM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of extended-infusion piperacillin-tazobactam in hospitalized patients with nosocomial infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4087–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalaria SN, Gopalakrishnan M, Heil EL. A population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics approach to optimize tazobactam activity in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e02093–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Benjamin DK Jr, Ross A, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of piperacillin using scavenged samples from preterm infants. Ther Drug Monit. 2012;34:312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thibault C, Lavigne J, Litalien C, Kassir N, Théorêt Y, Autmizguine J. Population pharmacokinetics and safety of piperacillin/tazobactam extended infusions in infants and children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e01260–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watt KM, Gonzalez D, Benjamin DK Jr, et al. Fluconazole population pharmacokinetics and dosing for prevention and treatment of invasive Candidiasis in children supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3935–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishihara N, Nishimura N, Ikawa K, et al. Population pharmacokinetic modeling and pharmacodynamic target attainment simulation of piperacillin/tazobactam for dosing optimization in late elderly patients with pneumonia. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman K, Gonzalez D, Swamy GK, Cohen-Wolkowiez M. Pharmacologic studies in vulnerable populations: using the pediatric experience. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39:532–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H, Zhang C, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Chen L. Clinical outcomes with alternative dosing strategies for piperacillin/tazobactam: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.High KP. 2017. Infection: general principles. Chapter 125. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S, Supiano MA, Ritchie C, eds. Hazzard’s Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, Seventh Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardakas KZ, Voulgaris GL, Maliaros A, Samonis G, Falagas ME. Prolonged versus short-term intravenous infusion of antipseudomonal β-lactams for patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:108–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes NJ, Liu J, O’Donnell JN, et al. Prolonged infusion piperacillin-tazobactam decreases mortality and improves outcomes in severely ill patients: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tannous E, Lipman S, Tonna A, et al. Time above the MIC of piperacillin/tazobactam as a predictor of outcome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e02571–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson JM. Antimicrobial pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:609–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellman-Weiler Weiss G. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and therapy of infections in elderly patients--a mini-review. Gerontology. 2009;55:241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karino F, Miura K, Fuchita H, et al. Efficacy and safety of piperacillin/tazobactam versus biapenem in late elderly patients with nursing- and healthcare-associated pneumonia. J Infect Chemother. 2013;19:909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindeman RD, Tobin J, Shock NW. Longitudinal studies on the rate of decline in renal function with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baba M, Shimbo T, Horio M, et al. Longitudinal study of the decline in renal function in healthy subjects. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ElDesoky ES. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic crisis in the elderly. Am J Ther. 2007;14:488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangoni AA, Jansen PA, Jackson SH. Under-representation of older adults in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies: a solvable problem? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes NJ, MacVane SH, Kuti JL, Scheetz MH. Impact of loading doses on the time to adequate predicted beta-lactam concentrations in prolonged and continuous infusion dosing schemes. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:905–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beal SL. Ways to fit a PK model with some data below the quantification limit. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2001;28:481–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamsen KM, Patel K, Nieforth K, Kirkpatrick CMJ. A regression approach to visual predictive checks for population pharmacometric models. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2018;7:678–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrose PG, Bhavnani SM, Rubino CM, et al. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: iťs not just for mice anymore. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mouten JW, Dudley MN, Cars O, Derendorf H, Drusano GL. Standardization of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) terminology for anti-infective drugs: an update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:601–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landersdorfer CB, Bulitta JB, Kirkpatrick CMJ, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of piperacillin at two dose levels: influence of nonlinear pharmacokinetics on the pharmacodynamic profile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Roberts MS, Robertson TA, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis and without renal dysfunction: intermittent bolus versus continuous administration? Monte Carlo dosing simulations and subcutaneous tissue distribution. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krueger WA, Bulitta J, Kinzig-Schippers M, et al. Evaluation by monte carlo simulation of the pharmacokinetics of two doses of meropenem administered intermittently or as a continuous infusion in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1881–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig WA. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–10; quiz 11–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drusano GL. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of 'bug and drug'. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andersen MG, Thorsted A, Storgaard M, Kristoffersson AN, Friberg LE, Öbrink-Hansen K. Population pharmacokinetics of piperacillin in sepsis patients: should alternative dosing strategies be considered? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02306–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehmann L, Zoller M, Minichmayr IK, et al. Development of a dosing algorithm for meropenem in critically ill patients based on a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;54:309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig WA. The pharmacology of meropenem, a new carbapenem antibiotic. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24 Suppl 2:S266–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Kirkpatrick CMJ, et al. Effect of different renal function on antibacterial effects of piperacillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa evaluated via the hollow-fibre infection model and mechanism-based modelling. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:2509–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergen PJ, Bulitta JB, Kirkpatrick CMJ, et al. Substantial impact of altered pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients on the antibacterial effects of meropenem evaluated via the dynamic hollow-fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e02642–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sörgel F, Kinzig M. The chemistry, pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of piperacillin/tazobactam. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31 Suppl A:39–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are to be made available as widely as possible, while safeguarding the privacy of participants, and protecting confidential and proprietary data.