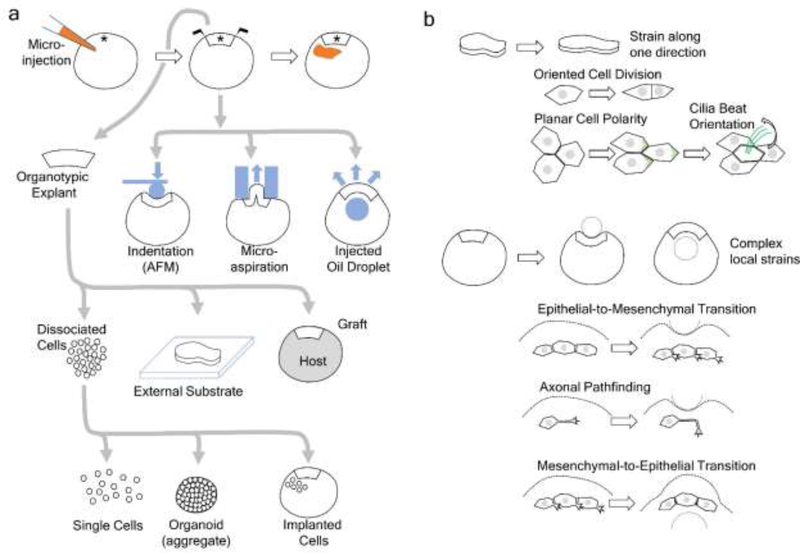

Figure 1. Diverse approaches to characterize and measure biomechanical properties in Xenopus.

a) Gain- or loss-of-function reagents (orange) can be injected into embryos at 1-cell or other early cleavage stages, and target tissues can be identified from 32- or gastrula stage fate maps (*). The whole embryo can be subjected to biomechanical manipulations (blue, device; blue arrows indicate force) to quantify mechanical properties or to apply specific deformations. Organotypic explants that preserve tissues in their native context can be isolated microsurgically. These explants an cultured on external substrates, which allow precise control of the microenvironment, or grafted into a host embryo (grey) where the mechanical microenvironment has been altered. Cell-cell and tissue-tissue interactions can be disrupted by dissociating the explant into single cells, which can be studied as-is by conventional in vitro methods or re-aggregate into an organoid. Cells may also be implanted into whole embryos to observe their reintegration into a native or perturbed microenvironment. b) Tools developed for biomechanical testing can also be used to apply defined strains or deformations to investigate the role of those mechanical cues in guiding cell behaviors. Organotypic explants can be subjected to defined strains to evaluate the role of anisotropic strain on cell division. Tissue strain, anologous to those occurring during epiboly, can specify the planar cell polarity and beat orientation of ciliated cells in both the epidermis and left-right-organizer. Manipulations of whole embryos with indentation or injection of oil droplets can instruct pathfinding in axons and modulate phenotypic transitions between mesenchymal and epithelial cell types. See the main text for more details.