Abstract

Previous research suggests that out-of-home placement experiences increase risk for mental health problems and criminal involvement. However, few studies have examined the mechanisms whereby out-of-home placement increases risk for these outcomes. The present study examines whether sleep problems in part explain the relationship between childhood placement experiences and depression and anxiety and criminal arrests in adulthood. Data are from a prospective longitudinal study of 531 children with documented cases of childhood maltreatment (14% with no out-of-home placement, 68% placed solely for abuse and/or neglect, and 18% placed for maltreatment and delinquency) who were followed up into adulthood. Cases are from 1967 −1971 from a metropolitan county in the Midwest. Sleep problems were assessed in young adulthood (Mage = 29 years). Depression and anxiety symptoms and arrest records were assessed in middle adulthood (Mage = 40 years). Structural equation modeling was used to test hypotheses. Both types of out-of-home placement experiences (for maltreatment only and for maltreatment and delinquency) predicted more sleep problems in adulthood across all models. Sleep problems in young adulthood predicted higher levels of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood, but not criminal arrests. Sleep problems mediated the relationship between placement only and internalizing symptoms and results differed for male, female, White, and Black individuals examined separately. Using court-substantiated cases of childhood abuse and neglect, this study demonstrates the long-term negative consequences of out-of-home placement experiences for sleep problems and anxiety and depression in adulthood. More attention is needed to insure adequate sleep for maltreated children.

Keywords: placement, maltreatment, sleep problems, mental health, arrests, longitudinal

Introduction

Adverse consequences of child abuse and neglect are well-documented in the literature, including lower levels of education and employment (Currie & Widom, 2010), higher rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Kisely et al., 2018; Widom, 1999; Widom et al., 2007), poorer physical health outcomes (Danese et al. 2007; Min et al. 2013; Widom et al., 2012), and higher rate of delinquency, crime, and violence (De Jong & Dennison, 2017; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Mersky et al., 2012). Abused and neglected children are also at risk for being removed from their home and placed in foster care (Pelton, 2013; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2021). These out-of-home placement experiences (including foster care, kinship care, or institutional (group) care (Barth, 2002), have been linked to increased psychopathology (Almquist et al., 2020; Gypen et al., 2017) and criminal involvement (Berger et al., 2016; Crawford et al., 2018; Dregan & Gulliford, 2012; Jonson-Reid & Barth, 2000; Lindquist & Santavirta, 2014; Ryan & Testa, 2005).

To our knowledge, no study has examined the interrelationships among out-of-home placement experiences, sleep problems, and criminal behavior and mental health, prospectively. One study relates out-of-home placement experiences and adult sleep problems (Fusco, 2020) and several studies relate sleep problems and internalizing problems (Scott et al., 2021) and delinquency and crime (Backman et al., 2015; Meldrum et al., 2015; Peach & Gaultney, 2013; Raine & Venables, 2017). Delinquency and crime are measured in a variety of ways, including self-reports of delinquency using questionnaires and scales, official arrest data, criminal convictions, or juvenile court petitions. Using data from a prospective longitudinal study (Widom, 1989), the present research examined whether out-of-home placement experiences are associated with sleep problems during young adulthood and whether sleep problems in part explain (mediate) the relationship between placement and later anxiety and depression and criminal arrests.

Consequences of Out-of-home Placement

One early study by Widom (1991) examined the impact of placement experiences on later crime and delinquency in a sample of maltreated children. Because children may have very different histories before out-of-home placement, three placement groups were identified: no out-of-home placement, placement solely for abuse and/or neglect, and placement for abuse and neglect and delinquency (that is, the child’s own delinquency). Widom (1991) found that out-of-home placement by itself did not lead to a significant increase in delinquent and criminal behaviors. Only when maltreated children were also placed out of the home for delinquency was the risk of delinquent and criminal arrests higher compared to those who remained at home or were placed for abuse and neglect only. These findings were replicated in a follow-up study (DeGue & Widom, 2009), that conducted a criminal history search five years later when the participants were older.

Findings from other studies are mixed. In one study involving two birth cohorts (1983 and 1984) of maltreated children in Chicago, Ryan and Testa (2005) found an increased risk for delinquency (operationalized as juvenile delinquency petitions) associated with out-of-home placement for both males and females. However, in another study that compared two groups of maltreated children (ages 9-12) in Los Angeles, one with a recent out-of-home placement experience and the other without placement, Mennen et al. (2010) found no significant differences in delinquency and internalizing and externalizing problems (assessed via caregiver- and child-reports).

A study in Sweden by Lindquist and Santavirta (2014) found that young adults with a history of placement had a higher likelihood of criminal convictions compared to a control group of children who were investigated by the child welfare committee but never placed. However, the increased risk for adult criminal involvement was only if the reason for placement was determined to be the child’s own behavior [similar to the earlier findings of Widom (1991)]. Another study in Finland found that young adults who had experienced out-of-home placements during early childhood had higher rates of criminal convictions as well as higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to a demographically matched control group (Côté et al., 2018). Although these studies were conducted outside of the United States and their findings may not be generalizable to US samples, both studies are longitudinal and provide evidence of the impact of out-of-home placements.

Out-of-home placement experiences are likely to have a continued effect on a person’s development and well-being. For example, many studies indicate that after leaving foster care, individuals experience barriers to education, employment, income, and housing stability, and a lack of supportive social networks (Barth, 1990; Buehler et al., 2000; Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001; Crawford et al., 2015; Hook & Courtney, 2011; Reilly, 2003), stresses that can lead to sleep problems. Out-of-home placement experiences are often associated with multiple moves, and these frequent changes in residence can increase risk for sleep problems.

At present, very little research exists on the relationship between placement experiences and sleep. One small study with young children (n = 25) found that more time spent in care was associated with sleep problems (that is, the difficulty waking-up in the morning, sleepiness and falling asleep during the day) (Dubois-Comtois et al., 2016). In a cross-sectional study of young adults (ages 18-24), Fusco (2020) found that foster care alumni reported significantly poorer sleep, including fewer hours of sleep, longer sleep onset latency, and more nighttime awakenings, compared to low income individuals without out-of-home placement experiences, despite controlling for childhood maltreatment and trauma exposure.

Sleep and Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

Sleep is essential for maintaining cognitive and affective functions. Serious sleep loss has been shown to negatively affect attention, executive function, memory, and learning (Walker, 2008). Poor sleep quality has been associated with more frequent and intense expressions of self-reported anger, hostility, and aggression among healthy adults (Kamphuis et al., 2014). According to Logan and McClung (2019), circadian disruptions at different life stages may be linked to specific neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders that typically emerge during these life periods.

There is a large body of work that relates sleep problems (including insomnia symptoms, daytime sleepiness, poor quality sleep, and more awakenings) and anxiety and depression (McMakin & Alfano, 2015; Pieters et al., 2015; Roberts & Duong, 2014). In adults, sleep disturbances were associated with an increased likelihood of depression three years later (Breslau et al., 1996). Longitudinal studies have reported relationships between sleep problems and sleep deprivation and internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents (Pieters et al., 2015; Roberts & Duong, 2014). A recent meta-analysis (Scott et al., 2021) reported a consistent longitudinal link between sleep problems (broadly defined) and the onset of major mental disorders (including depression) in adolescence and early adulthood.

Most of the existing research that examines the relationship between sleep problems and externalizing behaviors focuses on sleep characteristics during childhood or adolescence. In a general population sample of school-aged children, Sadeh et al. (2002) found that behavior problems (based on parental reports on the CBCL) were more prevalent among “poor sleepers” than “good sleepers.” In another cross-sectional study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents in Finland (Backman et al., 2015), insufficient sleep was associated with adolescent property crime and violent behavior, controlling for participant’s sex, parental supervision, and psychopathic traits. Analyzing Add Health data (I and II Waves), Catrett and Gaultney (2009) did not find a relationship between sleep problems and delinquency. Among children with ADHD, sleep problems did not significantly predict externalizing problems one-year later (Mulraney et al. 2016). A study by Raine and Venables (2017) found that self-reported sleepiness during adolescence predicted higher rates of criminal convictions, controlling for adolescent antisocial behavior (reported by teachers).

The Current Study

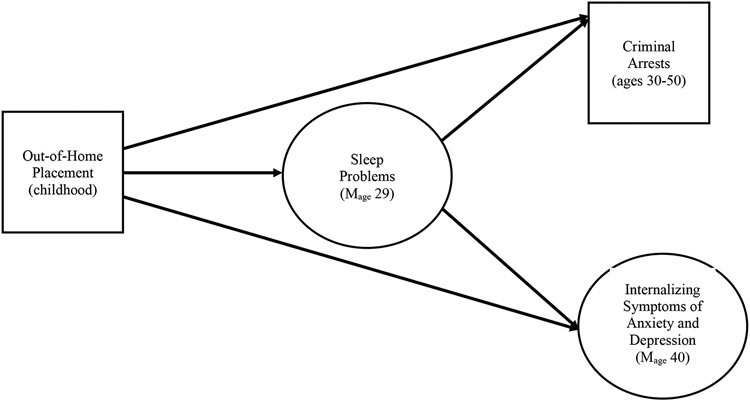

This prospective study examines the relationships among out-of-home placement experiences, sleep problems later in life, and subsequent adult arrests and internalizing symptoms of depression and anxiety. We seek to determine whether: (1) out-of-home placement experiences are associated with sleep problems; (2) out-of-home placement experiences predict externalizing (criminal arrests) and/or internalizing outcomes (anxiety and depression) in middle adulthood; (3) sleep problems in young adulthood predict more arrests and greater internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression; and (4) sleep problems in young adulthood in part explain the relationship between out-of-home placement experiences and adult arrests and depression and anxiety in middle adulthood. Figure 1 presents a schematic diagram of the hypothesized model illustrating the potential role of sleep problems as a mediator of the relationship between out-of-home placement experiences and two subsequent outcomes (criminal arrests and internalizing symptoms in later life). This model will be tested for the sample overall. In addition, because sex and race differences have been reported in rates of out-of-home placements, arrests, and internalizing symptoms (e.g., Abajobir et al., 2017; Essau et al., 2010; Widom, 1991), we also test this model for females, males, Black and White individuals separately. However, because of the dearth of existing literature on this issue, we make no predictions about race or sex differences in these relationships.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the hypothesized model illustrating the potential role of sleep problems as a mediator of the relationship between out-of-home placement experiences and two subsequent outcomes (criminal arrests and internalizing symptoms in later life). Out-of-home placement refers to placement for abuse or neglect and placement for abuse or neglect plus delinquency, compared to no out-of-home placement. Sleep problems were assessed with responses to questions about trouble falling asleep, waking up too early, and sleeping too long. The latent factor of internalizing symptoms includes scores on standardized assessments of depression and anxiety.

Methods

Design and Participants

The data used in the present study are from a larger study of children with documented cases of maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse and neglect) and matched controls (Widom, 1989). Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971. To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that temporal sequence was clear (that is, child neglect or abuse led to subsequent outcomes), maltreatment cases were restricted to those in which the children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident.

Because the focus of this work is on outcomes associated with out-of-home placement experiences, the sample for the present study was restricted to the maltreated children whose cases were processed in the family court at the time. The availability of specific care types varies across historical time periods. Thus, at the time these abuse and neglect cases were being processed (during the late 1960s and early 70s), out-of-home placement experiences were largely traditional foster care and placement in a Guardian’s Home. The great majority (about 80%) of these abused and neglected children who were placed outside the home were placed in foster care or the Guardian’s home. A small percent was placed in facilities for children with special psychiatric or medical needs [see Widom (1991) for more details].

The analytic sample was 531 participants, mean age = 28.97 (SD = 3.69, range = 19.25 to 38.48) at the time of the first interview. The sample was 52.2% male and 64.8% White, non-Hispanic. Because we wanted to examine whether there were differences in the experiences of Black and White children, the sample was restricted to White and Black participants only. The very small group of Hispanic and other individuals who identified as another ethnicity were excluded.

Procedures

The information used here was collected during the first and second in-person interviews (1989-1995 and 2000-2002) and from official arrest records. Interviews took place in the participant’s home or other convenient place. The interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the participants' group membership, and to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group. Participants were also blind to the purpose of the study and were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in that area during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each wave of the study and participants were provided written, informed consent. For individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was presented and explained verbally. This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Program at The City University of New York (Protocol #: 2015-0133).

Measures and Variables

Independent Variable: Out-of-home Placement

The information about placement experiences (and type of out-of-home placement) was included in the files of the individual children. Some children were placed only for abuse and neglect, whereas other children were placed for abuse and neglect and concurrent delinquency. Fourteen percent of the sample had no out-of-home placement, 68% were placed solely for abuse and/or neglect, and 18% were placed for maltreatment and delinquency. Two binary variables were created to reflect (1) whether the participant had experienced placement only for maltreatment (coded as 1) or no placement (coded as 0) and (2) placement for maltreatment and delinquency (coded as 1) or no placement (coded as 0).

Potential Mediator: Sleep Problems in Young Adulthood

As part of interview 1, participants were asked three questions to indicate whether they ever had a period of two weeks or more when nearly every day they had: (1) trouble sleeping, (2) waking up too early, or (3) sleeping too much. Responses to each of these three questions were coded as 0 = no, 1 = yes and, thus, total scores ranged from 0-3 (M = 0.82, SD = 1). Analyses were conducted to determine whether the three questions formed a latent construct, tentatively labeled “sleep problems”. Confirmatory factor analysis results showed factor loadings of .68, .48, .59, for these three questions overall, p < .001. Together with the model fit information, these loadings indicate that there is justification for a latent factor.

Outcome Variables

Crime.

Adult criminal behavior was operationalized as the number of arrests that were recorded after the first interview (when the mediator variable was assessed), representing the time period of approximately ages 30 to 50. Participants’ arrest records were gathered from local, state, and Federal levels of law enforcement. Records were searched three times for each participant; the first search occurred between 1986 and 1987, the second search in 1994, and the third search between 2012 and 2013. With the exception of traffic offenses, the full range of crimes was represented, including arrests for violence, property crimes, sex offenses, public order offenses, and child maltreatment and endangerment. The number of crimes in the whole sample was Mean = 3.00 (SD = 7.18), range = 0 to 78.

Depression.

Depression was assessed at interview 2 (mean age = 39.51), using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item self-report measure with high internal consistency for general and psychiatric populations. Participants were asked to indicate how they felt during the past week on a 4-point scale ranging from rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day) to most or all of the time (5–7 days). Because one of the CES-D items asked about sleep, this item was removed to insure independence of the predictor and outcome variables. Total scores ranged from 0 to 51 (M = 13.82, SD = 10.94) with higher scores indicating more depression symptoms (α = 0.90).

Anxiety.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988) was administered at interview 2 as well. The BAI is a 21-item self-report measure of anxiety in which participants were asked to rate how much they have been bothered by specific symptoms over the past week on a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely). Total scores ranged from 0 to 57 (M = 10.54, SD = 11.11, α = 0.93) with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety symptoms. High internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and good concurrent and discriminant validity have been reported for the BAI (Beck et al., 1988; Beck & Steer, 1993).

In structural equation models, the scores of depression and anxiety were used as indicators of a latent construct labeled as “internalizing problems”. Evidence from the confirmatory factor analyses provided support for such representation (factor loadings = 0.80 and 0.87, for anxiety and depression, respectively).

Control variables.

Sex, age, and race were included as control variables in the overall models. Sex was coded as male (0) or female (1). Race was based on self-identification and for the present analyses, it was dichotomized into White = 1 and Black = 0. Age was measured in years.

Statistical Analysis

The first step in the analyses was to compute descriptive statistics for the study variables. This was followed by a set of ANOVAs to test mean-level differences in the mediator and the outcome variables across the three placement statuses. Post hoc Scheffé tests were conducted to identify specific group differences. The next step involved a series of structural equation models (SEM) to test for mediation, performed for the total sample as well as separately for female, male, White, and Black participants. Out-of-home placement experience was the independent variable, sleep problems in adulthood (age 29) the hypothesized mediator, and adult criminal arrests and a latent construct representing internalizing symptoms of depression and anxiety were the outcome variables. Although there are several approaches to examining mediation, we followed the most up-to-date recommendations (Rucker et al., 2011). This approach focuses on testing the mediation effects themselves rather than on finding the difference in direct effects using the stepwise procedure. Accordingly, the indirect effects were tested using bootstrapping and were assessed based on 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (BCCI).

Results were evaluated based on overall model fit indices, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), as well as on examining structural paths, their size and statistical significance. The values of CFI and TLI > .90, and RMSEA < .08 indicate acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1998). Analyses controlled for participant’s sex, race, and age unless conducted for specific racial or sex groups. The Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data. We used SPSS (IBM Corp., 2016) version 24.0 for the descriptive statistics and Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) to test structural equation models.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample and Bivariate Comparisons Among the Placement and No Placement Groups

Descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics of the sample and outcome variables are reported in Table 1. Overall, the majority of children had been placed outside the home for maltreatment only (68%), with 17.7% placed for maltreatment and delinquency, and the smallest percent (14.3%) with no placement. There were significant differences in the distribution of placement experiences by sex (χ2 (2) = 18.02, p <.001) and race (χ2 = (2) = 17.09, p <.001). Those placed for maltreatment and delinquency were significantly more likely to be male (χ2 (1) = 15.80, p <.001), whereas the rates for males did not differ for no placement and placement only for maltreatment. Black children were more likely to be placed for maltreatment and delinquency (χ2 (1) = 8.71, p <.003) or not placed (χ2 (1) = 4.03, p =.045) and less likely to be placed for maltreatment only) (χ2 (1) = 16.14, p <.001). The three placement groups did not differ significantly in terms of age at the time of the first interview.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for maltreated children with no placement, placement for maltreatment, and placement for maltreatment and delinquency

| No placement | Placement for maltreatment |

Placement for maltreatment and delinquency |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | N = 76 | N = 361 | N = 94 |

| Sex | |||

| Female (n, %) | 44 (17.3%) | 183 (72.0%) | 27 (10.6%) |

| Male (n, %) | 32 (11.6%) | 178 (64.3%) | 67 (24.2%) |

| Race | |||

| White, non-Hispanic (n, %) | 41 (11.9%) | 255 (74.1%) | 48 (14.0%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic (n, %) | 35 (18.7%) | 106 (56.7%) | 46 (24.6%) |

| Age at interview 1 (M, SD) | 28.70 (3.68) | 29.04 (3.67) | 28.90 (3.78) |

| Mediator and Outcomes | |||

| Sleep problems in young adulthood (M, SD) | 0.46 (0.81)a | 0.88 (1.03)b | 0.94 (1.09)b,c |

| Adult Arrests (M, SD) | 2.71 (7.50)a | 1.91 (5.83)a | 8.63 (10.71)b |

| Depression symptoms in middle adulthood | 14.63 (12.48) | 13.47 (10.55) | 14.56 (11.15) |

| Anxiety symptoms in middle adulthood | 9.29 (10.59) | 10.91 (11.17) | 11.37 (11.42) |

Note. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using post hoc Scheffe tests as part of one-way ANOVAs. Statistically significant mean-level differences are indicated by superscripts (a, b, and c), where different superscripts denote significant differences between the groups and where the same superscript indicates that the differences are not significant.

There were significant mean-level differences in sleep problems across placement groups: F(2, 538) = 5.93, p = .003. Post hoc Scheffé tests showed that individuals who had not been placed (the no-placement group) had significantly fewer adult sleep problems compared to those who had been placed for maltreatment only (ΔM = −0.41, p = .005) (note that “Δ” or delta denotes a change or difference and ΔM indicates the difference in two means) and those who had been placed for maltreatment and delinquency (ΔM = −0.48, p = .010). The two placement groups were not significantly different from each other in terms of sleep problems (ΔM = −0.06, p = .873).

Table 1 also shows that there were significant differences among the three groups in the number of adult arrests: F(2, 528) = 32.96, p < .001. Post hoc Scheffé tests showed that individuals who had been placed for maltreatment and delinquency had a significantly higher mean number of adult arrests than individuals who had not been placed outside the home (ΔM = −5.92, p < .001) and those who had been placed only for maltreatment (ΔM = −6.72, p < .001). The difference between the no placement and placement only groups in mean number of arrests was not statistically significant (ΔM = 0.80, p = .677). There were no significant mean-level differences between the three placement groups in either depression or anxiety.

Sleep Problems as a Mediator between Placement and Adult Arrests and Internalizing Symptoms

Results from the SEMs conducted for the whole sample are shown in Table 2. The models demonstrated excellent fit. Compared to no placement, out-of-home placement only and placement for maltreatment and delinquency (β = 0.41, p < .001) predicted sleep problems (β = 0.25, p = .003). Only out-of-home placement for maltreatment and delinquency had a significant direct effect on adult arrests (β = 0.23, p = .013). Sleep problems did not predict adult arrests and there were no significant indirect effects of placement on adult arrests through sleep problems.

Table 2.

Structural equation models testing whether placement experiences predict adult criminal arrests and internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression via sleep problems

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | P | χ 2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting Adult Arrests | 13.43 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.03 | ||||

| Total effect | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.15, 0.07 | .603 | ||||

| Direct: Placement only -> Adult arrests | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.18, 0.04 | .283 | ||||

| Placement only-> Sleep problems | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.10, 0.42 | .003 | ||||

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.14 | 0.09 | −0.05, 0.30 | .118 | ||||

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.00, 0.10 | .184 | ||||

| 4.59 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |||||

| Total effect | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.10, 0.39 | <.001 | ||||

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency-> Adult arrests | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.04, 0.41 | .013 | ||||

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.41 | 0.11 | 0.21, 0.66 | <.001 | ||||

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.16, 0.30 | .551 | ||||

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems ->Adult arrests | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.07. 0.17 | .605 | ||||

| 21.49 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.03 | |||||

| Predicting Internalizing Symptoms | ||||||||

| Total effect | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.12, 0.12 | .855 | ||||

| Direct: Placement only -> Internalizing symptoms | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.22, 0.06 | .417 | ||||

| Placement only-> Sleep problems | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.08, 0.40 | .002 | ||||

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing symptoms | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.07, 0.47 | .014 | ||||

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02, 0.18 | .072 | ||||

| 9.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |||||

| Total effect | 0.05 | 0.11 | −0.16, 0.27 | .655 | ||||

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency-> Internalizing | −0.12 | 0.13 | −0.41, 0.13 | .375 | ||||

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.20, 0.61 | <.001 | ||||

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.11, 0.88 | .036 | ||||

| Placement for CM & delinquency-> Sleep problems ->Internalizing | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.04, 0.56 | .112 |

Note. CM = child maltreatment. Placement only = placement for maltreatment only. Comparison group for both “placement only” and “placement for CM & delinquency” is “no-placement”. Beta = standardized coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. Analyses controlled for participants’ age, sex, and race.

Table 2 also shows that in models examining the impact of out-of-home placement only, sleep problems in young adulthood predicted greater internalizing symptoms (β = 0.25, p = .003) in middle adulthood. Similarly, in models examining the impact of placement for maltreatment and delinquency, sleep problems predicted internalizing symptoms (β = 0.41, p <.001). There was also a significant indirect effect for sleep problems to mediate the relationship between out-of-home placement only and internalizing symptoms (β = 0.07, 95% BCCI = 0.02, 0.18).

Sex Differences in the Roles of Placement and Sleep Problems

Tables 3 presents the results of SEM analyses for males and females separately. All models demonstrated good fit (details are available in Supplementary Materials). Among male participants, placement only and placement for maltreatment and delinquency predicted sleep problems (β = 0.33, p = .034, and β = 0.31, p = .036, respectively) and sleep problems in young adulthood predicted subsequent internalizing symptoms (β = 0.35, p = .051). Among female participants, placement only (but not placement for maltreatment and delinquency) predicted adult sleep problems (β = 0.21, p = .050). There was no evidence that sleep problems mediated the impact of placement on internalizing symptoms or adult arrests for males or females examined separately.

Table 3.

Structural equation models testing whether placement experiences predict adult criminal arrests and internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression via sleep problems for male and female participants separately

| Females | Males | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | P | Beta | SE | 95% CI | P | |

| Total effect | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.24, 0.05 | .164 | −0.01 | 0.07 | −0.17, 0.12 | .960 |

| Direct: Placement only-> Adult arrests | −0.12 | 0.11 | −0.31, 0.11 | .269 | −0.07 | 0.13 | −0.36, 0.07 | .659 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.00, 0.40 | .050 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.08, 0.74 | .034 |

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.06 | 0.15 | −0.31, 0.36 | .717 | 0.20 | 0.14 | −0.03, 0.53 | .353 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.06, 0.12 | .767 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.00, 0.65 | .657 |

| Total effect | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.08, 0.49 | .006 | 0.21 | 0.09 | −0.02, 0.36 | .025 |

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency-> Adult arrests | 0.25 | 0.16 | −0.12, 0.51 | .137 | 0.20 | 0.11 | −0.05, 0.37 | .054 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.32 | 0.17 | −0.13, 0.64 | .103 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03, 0.53 | .036 |

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.16 | 0.20 | −0.49, 0.65 | .581 | 0.02 | 0.15 | −0.29, 0.35 | .918 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency->Sleep problems->Adult arrests | 0.05 | 0.11 | −0.08, 0.36 | .654 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.12, 0.18 | .944 |

| Total effect | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.18, 0.14 | .659 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.18, 0.14 | .622 |

| Direct: Placement only-> Internalizing symptoms | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.24, 0.11 | .357 | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.48, 0.08 | .510 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.01, 0.39 | .039 | 0.32 | 0.14 | 0.02, 0.54 | .025 |

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing symptoms | 0.21 | 0.14 | −0.04, 0.51 | .138 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.02, 0.81 | .051 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.01, 0.16 | .284 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.00, 0.43 | .218 |

| Total effect | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.25, 0.03 | .135 | 0.17 | 0.13 | −0.09, 0.39 | .189 |

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency-> Internalizing | −0.17 | 0.11 | −0.38, 0.03 | .119 | 0.05 | 0.28 | −0.25, 0.36 | .855 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.31 | 0.19 | −0.19, 0.58 | .105 | 0.37 | 0.14 | 0.01, 0.62 | .008 |

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing symptoms | 0.19 | 0.18 | −0.17, 0.54 | .295 | 0.31 | 0.30 | −0.05, 0.66 | .344 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency->Sleep problems->Internalizing | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.03, 0.25 | .436 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.00, 0.38 | .667 |

Note. CM = child maltreatment. Placement only = placement for maltreatment only. Comparison group for both “placement only” and “placement for CM & delinquency” is “no-placement”. Beta = standardized coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval. Controlling for age and race. See Supplementary Material for model fit statistics.

Race Differences in the Roles of Placement and Sleep Problems

Table 4 presents the findings of the analyses for White and Black participants separately. Both types of placement experiences (out-of-home placement only and placement for maltreatment and delinquency) predicted sleep problems among Black participants (β = 0.33, 0.51, 0.34, and 0.47, p < .05 for all four different models), but not among White participants. For Black participants, in the model examining the impact of placement for maltreatment and delinquency, sleep problems predicted future internalizing problems (β = 0.51, p = .012) and there was a significant indirect effect indicating that sleep problems mediated the relationship between placement for maltreatment and delinquency and later internalizing problems for Black individuals (β = 0.07, 95% BCCI = 0.02, 0.18). As described in the statistical analysis section, the significance of indirect effects is based on confidence intervals, not p values.

Table 4.

Structural equation models testing whether placement experiences predict adult criminal arrests and internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression via sleep problems for White and Black participants separately

| White | Black | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | 95% CI | P | Beta | SE | 95% CI | P | |

| Total effect | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.12, 0.09 | .887 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.25, 0.09 | .458 |

| Direct: Placement only -> Adult arrests | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.16, 0.08 | .672 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.34. 0.07 | .283 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.02, 0.42 | .062 | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.03, 0.61 | .035 |

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.18 | 0.13 | −0.04, 0.50 | .180 | 0.15 | 0.18 | −0.35, 0.54 | .519 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.00, 0.18 | .388 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.05, 0.25 | .351 |

| Total effect | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.16, 0.42 | <.001 | 0.26 | 0.07 | −0.01, 0.50 | .042 |

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency-> Adult arrests | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.14, 0.55 | .019 | 0.20 | 0.18 | −0.26, 0.49 | .291 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.28 | 0.18 | −0.08, 0.63 | .161 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.09, 0.75 | .047 |

| Sleep problems -> Adult arrests | −0.05 | 0.20 | −0.73, 0.29 | .870 | 0.13 | 0.20 | −0.19, 0.78 | .542 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency->Sleep problems->Adult arrests | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.35, 0.10 | .919 | 0.07 | 0.13 | −0.07, 0.72 | .619 |

| Total effect | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.11, 0.14 | .619 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.22, 0.13 | .612 |

| Direct: Placement only -> Internalizing symptoms | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.16, 0.10 | .799 | −0.14 | 0.11 | −0.35, 0.08 | .222 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems | 0.20 | 0.10 | −0.01, 0.38 | .058 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.05, 0.55 | .005 |

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.24 | 0.14 | −0.01, 0.55 | .083 | 0.27 | 0.16 | −0.01, 0.57 | .085 |

| Placement only -> Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00, 0.20 | .256 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.01, 0.29 | .190 |

| Total effect | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.06, 0.21 | .334 | −0.01 | 0.14 | −0.28, 0.28 | .962 |

| Direct: Placement for CM & delinquency->Internalizing | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.19, 0.19 | .906 | −0.25 | 0.20 | −0.73, 0.07 | .229 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency -> Sleep problems | 0.28 | 0.17 | −0.11, 0.58 | .109 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.71 | .001 |

| Sleep problems -> Internalizing | 0.20 | 0.17 | −0.16, 0.55 | .265 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.02, 0.85 | .012 |

| Placement for CM & delinquency->Sleep problems->Internalizing | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.02, 0.28 | .478 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.56 | .103 |

Note. CM = child maltreatment. Placement only = placement for maltreatment only. Comparison group for both “placement only” and “placement for CM & delinquency” is “no-placement”. Beta = standardized coefficient; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval. Controlling for age, sex. See Supplemental Material for model fit statistics.

Discussion

Using data from a longitudinal study of the consequences of child abuse and neglect, the present study examined the relationships among out-of-home placement experiences in childhood, sleep problems in young adulthood, and criminal behavior and internalizing symptoms of depression and anxiety in middle adulthood. The first goal was to determine whether out-of-home placement experiences predicted sleep problems in young adulthood. These new results indicated that being placed outside the home in childhood for both maltreatment only and maltreatment and delinquency was significantly associated with reports of sleep problems in adulthood. These findings are consistent with the work of Fusco (2020) and demonstrate the long-term impact of out-of-home placement experiences, above and beyond the effects of maltreatment. Because adequate sleep is a necessary component of physical and mental health, these findings suggest that specific efforts should be made to improve sleep quality for children in placement. These results also reinforce efforts by clinicians who work with young adults to assess for sleep problems and encourage therapeutic techniques to prevent future anxiety and depression.

The second goal was to determine whether out-of-home placement experiences predicted externalizing (criminal arrests) and internalizing symptoms (anxiety and depression) in middle adulthood. These results indicate that only children who were placed outside the home for maltreatment and delinquency were at increased risk for adult arrests, consistent with previous research (Lindquist & Santavirta, 2014; Widom, 1991). Surprisingly, out-of-home placement experiences did not predict higher levels of depression and anxiety in middle adulthood. One possible explanation for this finding is that the levels of anxiety and depression in this sample overall are high (higher than the levels of anxiety and depression in samples of non-maltreated individuals) and this may reflect a ceiling effect. This is consistent with results published earlier showing that individuals with documented histories of child maltreatment had higher levels of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood compared to a matched group of children without maltreatment histories (Sperry & Widom, 2013). In a study of a Finnish birth cohort, Côté et al. (2018) found positive relationships between placement during childhood and depression and anxiety and criminal convictions during young adulthood; however, comparisons were made between children who were placed and those who were not placed but who represented the general population. This approach is different than the present study which represented an analysis of a sample that consisted only of maltreated children. It is also possible that the focus on middle adulthood (instead of young adulthood) and cultural differences might have impacted the findings. Finally, the present study examined the mediating effect of sleep using a longitudinal design with three rather than two time points.

We expected that sleep problems in young adulthood would predict adult arrests, although we did not find this to be the case. However, one difference between this research and earlier work is that we examined the role of sleep problems in young adulthood, whereas in earlier studies (e.g., Raine & Venables, 2017), sleep was assessed during adolescence. On the other hand, a number of laboratory studies with adults have demonstrated the effects of sleep deprivation on impulse control and poor decision making (Dan et al., 2020), risk factors for criminal involvement.

We found that sleep problems in young adulthood predicted internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood. This is consistent with previous work that has reported negative consequences of sleep problems during adulthood, including internalizing symptoms and more pronounced cognitive decline (Hajali et al., 2019; Hein et al., 2020). Sleep has also been shown to have a bidirectional relationship with mental health disorders including depression and anxiety (Jansson-Fröjmark & Lindblom, 2008) and there is evidence of sleep disruptions leading to disruptive behaviors (Raine & Venables, 2017; Wong et al., 2009). Using a very different study sample, these new findings demonstrate the importance of sleep problems in adulthood and later internalizing symptoms.

Our findings indicate that out-of-home placement experiences had a substantial impact on sleep problems for both males and females. For males, both types of out-of-home placement experiences led to reports of sleep problems in adulthood, whereas placement only led to sleep problems later on for females. Unfortunately, it is difficult to draw parallels to the findings of previous research because the only study that examined the relationship between out-of-home placement experiences and sleep problems in adults did not report findings of sex differences (Fusco, 2020).

A surprising finding was that sleep problems predicted internalizing symptoms later in adulthood for males only. In the child maltreatment field, the assumption has been that maltreated male children go on to externalize and become perpetrators of violence, whereas female maltreated children go on to internalize and become depressed (Widom, 2000). Females are thought to be more responsive to stress (Bangasser et al., 2010). Others have suggested that differences in the nature of the stressors experienced by males and females determines differences in depression. For example, it has been suggested that men are more likely to be affected by financial stress, whereas women are more strongly influenced by interpersonal stressful events (Kendler & Gardner, 2014). For male children in out-of-home placement experiences, both types of stressors (financial and interpersonal) exist. Another possibility is that males are less able to cope with stress and stress-induced sleep problems than females. One study reported that protective factors buffered the effects of sleep problems on the trajectory of suicidal ideation from adolescence through young adulthood, but the effect was found only for females, not males (Chang et al., 2021). Notwithstanding these possible explanations, these new results about maltreated males highlight the role of sleep problems and the importance of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood, contrary to the stereotypes of males only externalizing. Future research and clinical practice should consider sleep problems in understanding anxiety and depression in previously maltreated males.

These new findings suggest that both types of out-of-home placement experiences are harmful for Black maltreated children, whereas White maltreated children who were placed outside the home did not report more sleep problems. This is particularly striking given that the sample size for the White participants was almost twice as large as that of Black participants and accordingly had higher statistical power. However, the effect size for the Black participants was substantially greater than for the White participants. We found that sleep problems in young adulthood predicted higher levels of internalizing symptoms later on in middle adulthood only for Black individuals in this study and that sleep problems mediated the relationship between placement for maltreatment and delinquency and later internalizing problems in Black individuals. One possible explanation for these findings is that the Black youth in this study experienced racial discrimination, which in other studies has been linked to sleep problems (Fuller-Rowell et al. 2017; Slopen et al., 2016). Another possibility is that the arrangements for the Black maltreated children in this study resulted in their placements in homes in less desirable neighborhoods and that this may have made sleep problems more likely. There is some evidence to support this suggestion. In a study of predominantly African American youth with a history of physical abuse and/or neglect, Huang et al. (2016) found that these youth were placed in neighborhoods characterized by higher rates of poverty (i.e., percent below the poverty line, households on public assistance, and unemployed population) compared to the neighborhoods where the youth resided prior to placement.

Limitations

Despite notable strengths, several limitations need to be noted. The present findings are based on a sample of children with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect in one metropolitan Midwestern county during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In addition, the sample is skewed toward families from the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to the experiences of maltreated children from middle- and upper-class families, or from other geographic regions or living in different historical periods. The findings might also differ for children placed in foster care for reasons other than abuse or neglect. We are not able to generalize to the potential effects of current care provisions for children. Another concern is that the measure used to assess sleep problems was limited as it relied solely on self-report. Future work would benefit from a more comprehensive assessment of sleep by incorporating physiological recordings of sleep patterns (for example, polysomnography) or behavioral assessments (via actigraphy), and not only sleep quality but also quantity. However, subjective self-reports are still very important and need to be included in future studies, because diagnoses of insomnia, for example, require sleep complaints by the person, something that can be missed if measured by actigraphy or polysomnography alone. Finally, knowing the extent of depression and anxiety in childhood for these individuals would also be helpful to determine whether these findings reflect continuity in these symptoms. Unfortunately, given the design of this study, we do not have this information but would hope that these results might stimulate other researchers with this information to examine these questions.

Conclusion

Using court-substantiated cases of childhood abuse and neglect, the present study demonstrates the long-term negative consequences of out-of-home placement experiences for sleep, an important physical and mental health function, irrespective of the reason for placement. Given that sleep problems in young adulthood lead to higher levels of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood, further efforts should be made to facilitate sleep for maltreated children.

Supplementary Material

Public Policy Relevance.

In a longitudinal study of maltreated children, out-of-home placement experiences in childhood led to sleep problems in young adulthood and sleep problems in young adulthood led to higher levels of anxiety and depression in middle adulthood. These findings highlight the need for greater attention and efforts to facilitate sleep in placement settings. Ensuring that maltreated children have adequate sleep conditions may be one of the ways to reduce subsequent mental health problems.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants to the corresponding author from NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 2011-WG-BX-0013), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), NIA (AG058683), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Justice. The funding sources were not involved in the conduct of this research and the preparation of this manuscript. We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abajobir AA, Kisely S, Williams G, Strathearn L, Clavarino A, & Najman JM (2017). Gender differences in delinquency at 21 years following childhood maltreatment: A birth cohort study. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 95–103. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almquist YB, Rojas Y, Vinnerljung B, & Brännström L (2020). Association of child placement in out-of-home care with trajectories of hospitalization because of suicide attempts from early to late adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e206639–e206639. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman H, Laajasalo T, Saukkonen S, Salmi V, Kivivuori J, & Aronen ET (2015). Are qualitative and quantitative sleep problems associated with delinquency when controlling for psychopathic features and parental supervision? Journal of Sleep Research, 24(5), 543–548. 10.1111/jsr.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP (1990). On their own: The experiences of youth after foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 7(5), 419–440. 10.1007/BF00756380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP (2002). Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for the second century of debate. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute for Families [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, & Steer RA (1993). Beck Anxiety Inventory manual. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser DA, Curtis A, Reyes BA, Bethea TT, Parastatidis I, Ischiropoulos H, … & Valentino RJ (2010). Sex differences in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor signaling and trafficking: Potential role in female vulnerability to stress-related psychopathology. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(9), 896–904. 10.1038/mp.2010.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Cancian M, Cuesta L, & Noyes JL (2016). Families at the intersection of the criminal justice and child protective services systems. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 665(1), 171–194. 10.1177/0002716216633058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, & Andreski P (1996). Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biological Psychiatry, 39(6), 411–418. 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Orme JG, Post J, & Patterson DA (2000). The long-term correlates of family foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 22(8), 595–625. 10.1016/S0190-7409(00)00108-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catrett CD, & Gaultney JF (2009). Possible insomnia predicts some risky behaviors among adolescents when controlling for depressive symptoms. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 170(4), 287–309. 10.1080/00221320903218331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LY, Chang YH, Wu CC, Chang JJ, Yen LL, & Chang HY (2021). Resilience buffers the effects of sleep problems on the trajectory of suicidal ideation from adolescence through young adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 279, 114020. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté SM, Orri M, Marttila M, & Ristikari T (2018). Out-of-home placement in early childhood and psychiatric diagnoses and criminal convictions in young adulthood: a population-based propensity score-matched study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(9), 647–653. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30207-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, & Dworsky A (2006). Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work, 11(3), 209–219. 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00433.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Piliavin I, Grogan-Kaylor A, & Nesmith A (2001). Foster youth transitions to adulthood: A longitudinal view of youth leaving care. Child Welfare, 80(6), 685–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford B, Pharris AB, & Dorsett-Burrell R (2018). Risk of serious criminal involvement among former foster youth aging out of care. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 451–457. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford BL, McDaniel J, Moxley D, Salehezadeh Z, & Cahill AW (2015). Factors influencing risk of homelessness among youth in transition from foster care in Oklahoma: Implications for reforming independent living services and opportunities. Child Welfare, 94(1), 19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie J, & Widom CS (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 111–120. 10.1177/1077559509355316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan O, Cohen A, Asraf K, Saveliev I, & Haimov I (2020). The impact of sleep deprivation on Continuous Performance Task among young men with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 1087054719897811. 10.1177/1087054719897811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, & Poulton R (2007). Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(4), 1319–1324. 10.1073/pnas.0610362104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong R, & Dennison S (2017). Recorded offending among child sexual abuse victims: A 30-year follow-up. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 75–84. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGue S, & Widom C (2009). Does out-of-home placement mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and adult criminality? Child Maltreatment, 14(4), 344–355. 10.1177/1077559509332264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dregan A, & Gulliford MC (2012). Foster care, residential care and public care placement patterns are associated with adult life trajectories: population-based cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(9), 1517–1526. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0458-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois-Comtois K, Cyr C, Pennestri M-H, & Godbout R (2016). Poor quality of sleep in foster children relates to maltreatment and placement conditions. SAGE Open, 6(4), 2158244016669551. 10.1177/2158244016669551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, & Sasagawa S (2010). Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127(1-3), 185–190. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Rowell TE, Curtis DS, El-Sheikh M, Duke AM, Ryff CD, & Zgierska AE (2017). Racial discrimination mediates race differences in sleep problems: A longitudinal analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(2), 165–173. 10.1037/cdp0000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco RA (2020). Sleep in young adults: Comparing foster care alumni to a low-income sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 493–501. 10.1007/s10826-019-01555-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gypen L, Vanderfaeillie J, De Maeyer S, Belenger L, & Van Holen F (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic-review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74–83. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hajali V, Andersen ML, Negah SS, & Sheibani V (2019). Sex differences in sleep and sleep loss-induced cognitive deficits: The influence of gonadal hormones. Hormones and Behavior, 108, 50–61. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein M, Lanquart J-P, Loas G, Hubain P, & Linkowski P (2020). Alterations of neural network organization during REM sleep in women: implication for sex differences in vulnerability to mood disorders. Biology of Sex Differences, 11, 1–12. 10.1186/s13293-020-00297-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JL, & Courtney ME (2011). Employment outcomes of former foster youth as young adults: The importance of human, personal, and social capital. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(10), 1855–1865. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Ryan JP, & Rhoden MA (2016). Foster care, geographic neighborhood change, and the risk of delinquency. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 32–41. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson-Fröjmark M, & Lindblom K (2008). A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64(4), 443–449. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, & Barth RP (2000). From maltreatment report to juvenile incarceration: The role of child welfare services. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(4), 505–520. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00107-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis J, Dijk D-J, Spreen M, & Lancel M (2014). The relation between poor sleep, impulsivity and aggression in forensic psychiatric patients. Physiology & Behavior, 123, 168–173. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PS (2011). Sleep and attachment. In El-Sheikh M (Ed.), Sleep and development: Familial and socio-cultural considerations (pp. 49–78). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195395754.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, & Gardner CO (2014). Sex differences in the pathways to major depression: a study of opposite-sex twin pairs. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(4), 426–435. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13101375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisely S, Abajobir AA, Mills R, Strathearn L, Clavarino A, & Najman JM (2018). Child maltreatment and mental health problems in adulthood: birth cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(6), 698–703. 10.1192/bjp.2018.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist MJ, & Santavirta T (2014). Does placing children in foster care increase their adult criminality? Labour Economics, 31, 72–83. 10.1016/j.labeco.2014.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan RW, & McClung CA (2019). Rhythms of life: circadian disruption and brain disorders across the lifespan. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 20(1), 49–65. 10.1038/s41583-018-0088-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, & Widom CS (1996). The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 150(4), 390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMakin DL, & Alfano CA (2015). Sleep and anxiety in late childhood and early adolescence. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(6), 483–489. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum RC, Barnes JC, & Hay C (2015). Sleep deprivation, low self-control, and delinquency: A test of the strength model of self-control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 465–477. 10.1007/s10964-013-0024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennen FE, Brensilver M, & Trickett PK (2010). Do maltreated children who remain at home function better than those who are placed? Children and Youth Services Review, 32(12), 1675–1682. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, & Reynolds AJ (2012). Unsafe at any age: Linking childhood and adolescent maltreatment to delinquency and crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 49(2), 295–318. 10.1177/0022427811415284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min MO, Minnes S, Kim H, & Singer LT (2013). Pathways linking childhood maltreatment and adult physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(6), 361–373. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulraney M, Giallo R, Lycett K, Mensah F, & Sciberras E (2016). The bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and internalizing and externalizing problems in children with ADHD: a prospective cohort study. Sleep Medicine, 17, 45–51. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus User's Guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Fleming CB, Oxford ML, Zheng Y, & Spieker SJ (2016). Can parenting intervention prevent cascading effects from placement instability to insecure attachment to externalizing problems in maltreated toddlers?. Child Maltreatment, 21(3), 175–185. 10.1177/1077559516656398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peach HD, & Gaultney JF (2013). Sleep, impulse control, and sensation-seeking predict delinquent behavior in adolescents, emerging adults, and adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 293–299. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton LH (2013). Have child maltreatment and child placement rates declined?. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1816–1822. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters S, Burk WJ, Van der Vorst H, Dahl RE, Wiers RW, & Engels RC (2015). Prospective relationships between sleep problems and substance use, internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 379–388. 10.1007/s10964-014-0213-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, & Venables PH (2017). Adolescent daytime sleepiness as a risk factor for adult crime. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(6), 728–735. 10.1111/jcpp.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T (2003). Transition from care: status and outcomes of youth who age out of foster care. Child Welfare, 82(6), 727–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, & Duong HT (2014). The prospective association between sleep deprivation and depression among adolescents. Sleep, 37(2), 239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker DD, Preacher KJ, Tormala ZL, & Petty RE (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, & Testa MF (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(3), 227–249. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A, Gruber R, & Raviv A (2002). Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Development, 73(2), 405–417. 10.1111/1467-8624.00414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J, Kallestad H, Vedaa O, Sivertsen B, & Etain B (2021). Sleep disturbances and first onset of major mental disorders in adolescence and early adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 101429. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Lewis TT, & Williams DR (2016). Discrimination and sleep: a systematic review. Sleep Medicine, 18, 88–95. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry DM, & Widom CS (2013). Child abuse and neglect, social support, and psychopathology in adulthood: A prospective investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(6), 415–425. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel WM, & Germain A (2011). Insecure attachment is an independent correlate of objective sleep disturbances in military veterans. Sleep Medicine, 12(9), 860–865. 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child Maltreatment 2019. Available from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- Walker MP (2008). Cognitive consequences of sleep and sleep loss. Sleep Medicine, 9, S29–S34. 10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1989). Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(3), 355–367. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1991). The role of placement experiences in mediating the criminal consequences of early childhood victimization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61(2), 195–209. 10.1037/h0079252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1999). Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(8), 1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (2000) Understanding the consequences of child abuse and neglect. In Reece RM (Ed.) Treatment of Child Abuse. (Pp.339–361). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, & Czaja SJ (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(1), 49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Bentley T, & Johnson MS (2012). A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, & Zucker RA (2009). Childhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 10(7), 787–796. 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.