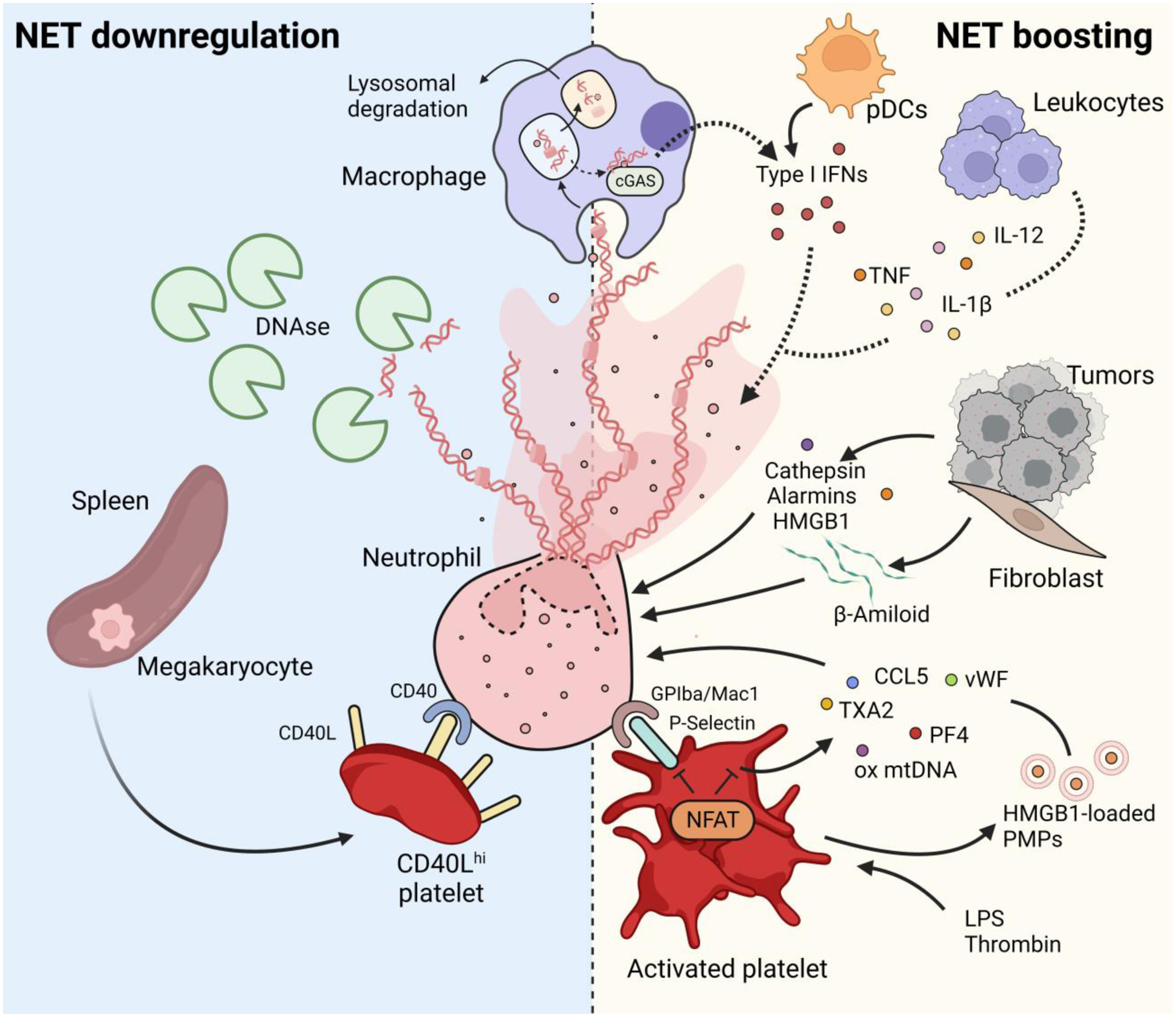

Figure 2. Neutrophil extrinsic regulators of NETosis.

NETs are removed from the circulation by DNases [80] and/or by macrophage phagocytosis and subsequent lysosomal degradation [81]. NET release can be negatively modulated by a population of CD40Lhi platelets, produced by megakaryocytes in the spleen during severe sepsis [120]. Macrophages can also boost NETosis. The cGAS pathway senses the presence of NETs and allows the production of type I IFNs. Macrophage-derived, as well as plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs)-derived [30] type I IFNs, in turn, favor NET release. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1β and IL-12, that are released by leukocytes during inflammation, also boost NETosis. Tumors also contribute to NET formation either directly by releasing cathepsin C and HMGB1, or indirectly by favoring the release of β-amyloid by tumor-associated fibroblasts [102]. Platelets, activated by either pathogens or via their activating receptors, potently induce NETs. Platelets stimulate NETosis either via direct contact with neutrophils that is mediated by the P-selectin-GPIba/Mac1 axis, or via release of soluble mediators such as thromboxane A2 (TXA2), platelet factor 4 (PF4), von Willebrand Factor (vWF), or CCL5. Platelets can also release oxidized mitochondrial DNA [116] and microparticles (PMPs) containing HMGB1 [96,97], that stimulate NETosis. The transcription factor NFAT is fundamental to modulate platelet activation by tuning P-selectin upregulation and granule release, and to prevent an exaggerated inflammatory response [113].