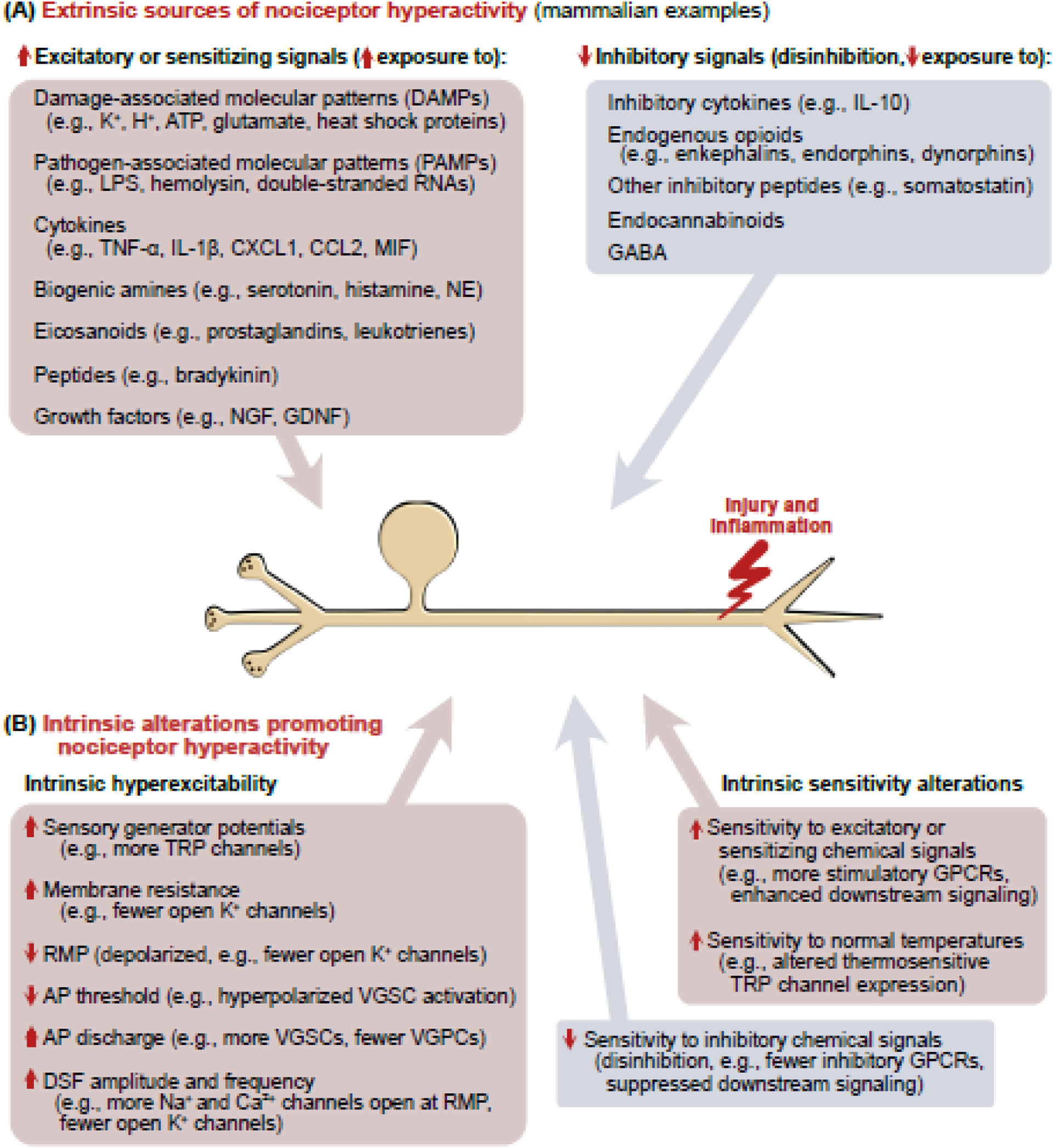

Figure 2. Sources of nociceptor hyperactivity following injury.

(A) Left: Some of the many extrinsic chemical signals implicated in mammals to excite and/or sensitize nociceptors. Many of these have multiple sources (e.g., glutamate and ATP are DAMPs released from ruptured cells but also are secreted exocytotically from various cell types including neurons). Right: Hyperactivity may also be promoted by reducing exposure to inhibitory chemical signals (disinhibition). (B) In principle, nociceptor hyperactivity can be promoted by intrinsic hyperexcitability via any or all the listed electrophysiological alterations [100,104]. Hyperactivity may also be promoted by increasing a nociceptor’s intrinsic sensitivity to excitatory or sensitizing sensory stimuli (including normal body temperature) or chemical signals, and by decreasing intrinsic sensitivity to inhibitory chemical signals. Abbreviations: AP, action potential; ATP, adenosine triphosphate, DSF, depolarizing spontaneous fluctuation; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; GDNF, glial-derived neurotrophic factor; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-10, interleukin 10; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; NGF, nerve growth factor; RMP, resting membrane potential; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor α; TRP, transient receptor potential; VGPC, voltage-gated potassium channel; VGSC, voltage-gated sodium channel.