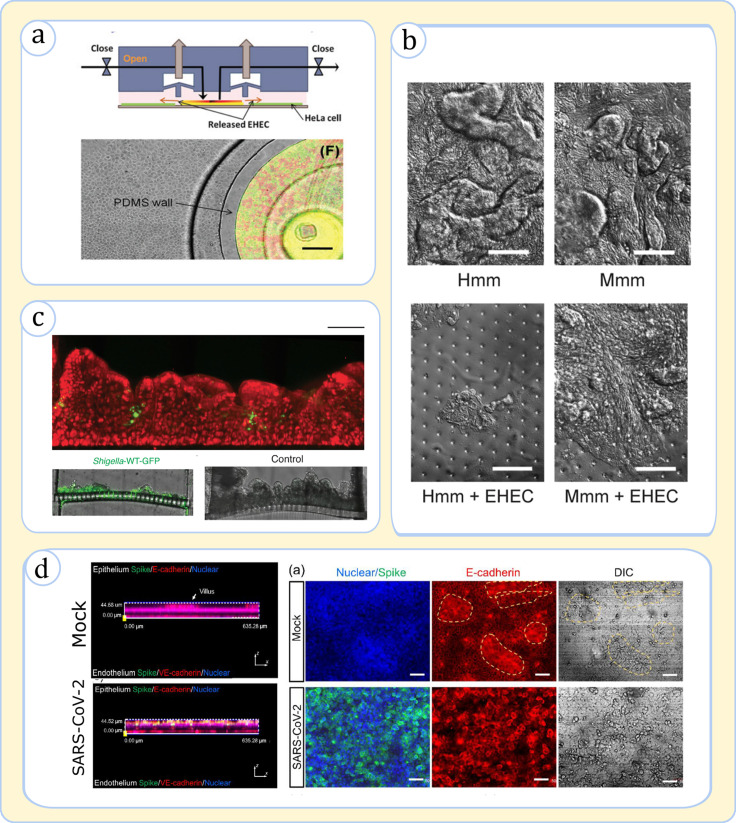

FIG. 7.

Application of gut-on-a-chip devices in modeling infections. (a) A modular microfluidic setup used to simulate EHEC bacterial infection upon interaction with commensal E. coli bacteria; (top) side-view sketch of the device illustrating the pneumatic actuation in the two upper channels lifts the barrier to allow mixing the bacteria with HeLa cells, the model intestinal cell used in the study; (bottom) the device top-view indicating coculture of pathogenic bacteria (red) and commensal (green) in an island before mixing with intestinal cells (grey). Used with permission from Kim et al., Lab Chip 10(1), 43 (2010). Copyright 2010 Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.115 (b) Simulation of EHEC infection on the intestinal chip with villi in the presence of murine and human microbiome metabolites, labeled Mmm and Hmm, respectively. The composition of Hmm causes the dissolution of villi as seen in the top-view images. Adapted with permission from Tovaglieri et al., Microbiome 7(1), 43 (2019). Copyright 2019 Authors, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.89 (c) The Shigella infection on a chip; (top) the side-view of the epithelium (red) reveals the recessed topographies are appropriate spots for bacterial attack (green); (bottom) the side-view of epithelial cells on the membrane indicates that infection causes the destruction of villi. Adapted with permission from Grassart et al., Cell Host & Microbe 26(3), 435 (2019). Copyright 2019 Elsevier.91 (d) Simulation of SARS-CoV-2 infection; (left) the virus infects the epithelium while having less effect on the endothelium as seen in the side-view image; (right) the viral attack (Spike protein: green) causes villi (marked with yellow dashed lines) destruction as seen in the top-view tissue images. Adapted with permission from Guo et al., Sci. Bull. 66(8), 783 (2021). Copyright 2021 Elsevier.118