Abstract

Introduction

Currently available data gives some credence to utility of VT induction studies in patients with stable ischemic cardiomyopathy, there are some unresolved questions as to define sensitive threshold for low-risk and the prognostic relevance of ill sustained or non-specific tachycardia on induction study. We evaluated potential ability of VT inducibility to predict likelihood of SHD (Structural heart disease) patients for subsequent arrhythmic or adverse cardiac events.

Material and Methods

All consecutive patients with syncope/documented arrhythmia who had VT induction done were included and patients with VT storm, ACS,uncontrolled HF were excluded. We studied in 4 groups-monomorphic VT, sustained polymorphicVT, ill sustainedVT/VF and no VT/VF induced. The primary-endpoints were – Sudden death, all-cause mortality and secondary-endpoints were – MACE (AICD shock, death,HF, recurrence of VT). We screened 411 patients and included 169 within inducible (n = 79) and non-inducible group (n = 90).

Results

There were a higher number of patients with coronary artery disease, LV dysfunction, patients on amiodarone in inducible group and no difference in usage of beta-blockers. Recurrence of VT, composite of MACE was significantly higher in inducible group (p < 0.05). Mortality was not different in 3 groups compared with no VT/VF group. We found that monomorphic VT group had significantly higher MACE as compared to others and also predicted recurrence of VT and AICD shock and showed a trend towards significance for prediction of mortality. Inducible patients on AICD had mortality similar to non-inducible group.

Conclusion

Induction of monomorphicVT/polymorphicVT with ≤3extrastimuli is associated with a higher number of MACE events on follow up. Induction of monomorphicVT predicts recurrence of VT/ICD shock.

Keywords: Ventricular tachycardia, Arrhythmia, VT induction

Abbreviations: VT, Ventricular tachycardia

Abbrevations

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- AICD

Automated intracardiac defibrillator

- HF

Heart failure

- MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- VF

Ventricular fibrillation

- VT

Ventricular tachycardia

1. Introduction

The risk of sudden cardiac arrest is dependent on many factors which include the presence of structural heart disease, ventricular function, presence of ischemia, the status of the autonomic nervous system and the presence of substrate for arrhythmia in the ventricles.1 Re-entry, triggered activity, or abnormal automaticity are three major categories of arrhythmia mechanisms thought to be responsible for the generation of ventricular arrhythmias. Wellen's et al2 in 1972 first described the induction and termination of ventricular tachycardia (VT) with timed extra stimuli suggesting a re-entrant mechanism. Over the years VT induction protocol as part of the evaluation of syncope or risk of SCD has evolved. While currently, available data gives some credence to the utility of VT induction studies in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, there are some unresolved questions – a) Is there a sufficiently sensitive threshold for a result derived from VT induction studies to classify the patient as low risk? b) does ‘non-specific’ or ill sustained tachycardia have relevance to prognosis? The relevance of the results can be assumed to be different for different substrates apart from ischemia but can be confirmed only by a long term follow up of patients who have undergone these studies.

In this study, we aimed to study the prognostic value of inducibility and implication of induced monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular flutter or fibrillation (VF) during programmed electrical stimulation in patients with structural heart disease.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

The study was done at our institute and patients were inclued from Jan 2009 to Dec 2016. It is a retrospective longitudinal observational study. We studied all consecutive patients who had documented ventricular tachycardia (including VF) or syncope, and structural heart disease (SHD) defined as any abnormality, or defect, of the heart muscle or the heart valves which is likely to cause a significant alteration to hemodynamics, structure or function of the heart. An echo and MRI (in indicated cases) were used to assess the structural abnormality. Of these, the patients who underwent VT induction study were included. The inclusion criteria were:1) Age ≥18 years, 2) Documented ventricular arrhythmia despite being on at least 2 anti-arrhythmic drugs, 3) history of syncope (excluding other causes) 3) Presence of structural heart disease as documented by echocardiography or non-invasive imaging (CT/MRI), 4) no prior history of VT induction study in the past.

The occurrence of events like syncope, hospital admission, ICD shock was gathered from hospital records and from OPD visits. Only the patients where follow-up was not possible physically, tele-communication was used. We contacted the patients through telephonic conversation in their native language or post mail. If we were unable to contact through these modalities we enquired about the patient through the village or community head. 20 patients could not be contacted from all the above measures and were excluded from the study. We excluded patients who had admission for VT storm, acute coronary syndrome, and uncontrolled heart failure. Further, patients who already had a device impanted earlier were not included to bring homogeneity to the study population. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

2.2. Procedure

Anti-arrhythmic drugs were withheld for at least five half-lives except for amiodarone which was withheld for at least 7 days (if taking amiodarone for atleast a month). The patients who were planned for VT induction study and were considered high risk for life threatening arrhythmias were hospitalised and kept under close observation. Apart from a standard protocol for assessing inducibility and risk stratification, VT induction was done to assess the drug efficacy in many. It was also considered where a potential precipitating factor like ischemia or dyselectrolytemia was abolished. A few of patients were taken up with a planned ablation. Pre-applied defibrillator pads were used at the beginning. An arterial line was secured before the beginning of the procedure. Patients who were on anticoagulation were shifted to heparin with monitoring of aPTT.Baseline measurement included the recording of baseline cycle length, and all necessary intervals (Atrial-His, His bundle-ventricular, His potential). Cardiac stimulation was carried out through the electrodes placed from an external stimulator and electrograms recorded. Extra-stimulus (ES) was delivered after run of eight paced beats (stimuli) and was labeled as S1 … …S2. The first ES was started ata coupling interval of 300 m s and then decreased in 10 msgaps. If the initial ES (S1S2) failed to induce VT, the subsequent ES was given 10 m s outside the ventricular effective refractory period (ERP) and an additional ES was added (e.g. S2S3) at a coupling interval of 300 m s. The response of extra-stimuli was recorded. Initial extra-stimuli were given through the right ventricular apex, followed by the RV outflow tract. The number of extra-stimuli and the site of extra-stimuli were recorded.

Definitions of VT induction protocol results3, 4, 5

-

o

Sustained monomorphic VT – Monomorphic VT lasting more than 30 s and cycle length (CL) more than 250 msec.

-

o

Monomorphic fast VT – Monomorphic VT lasting at least 10 s (if terminated by DC version) or 15 s (if spontaneously terminated) and CL less than 250 msec.

-

o

Polymorphic VT – Polymorphic or unstable QRS morphology with an average rate faster than 200 beats/min and requiring DC version or lasting more than 10 s and not falling into VF category

-

o

Ventricular fibrillation – VT with CL less than 200 msec, regardless of QRS morphology

-

o

Non-inducible - A response not fitting into either of the above definitions.

Inducibility defined by sustained monomorphic VT/polymorphic VT induced with ≤ 3extrastimuli lasting more than 10 s or requiring DC version.

2.3. Outcomes of study

Primary outcome included the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmia (documented VT, arrhythmic syncope, appropriate ICD interventions) and all-cause mortality including sudden death. Secondary outcomes included any event out of heart failure admissions, medication intolerance, or adverse effects, inappropriate ICD interventions.

2.4. Stastitics

Descriptive summaries are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical data, and as means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Continuous variableswere compared using Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test as appropriate, Group comparisons were made using χ2 tests. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses with log-rank analysis were performed to evaluate differences in freedom from the arrhythmic event, ICD shock (if implanted). Univariate and multivariate analysis were done from the Cox proportional hazard model. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package (release 16.0, SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill).

3. Results

In our study we screened 411 consecutive patients who underwent ventricular tachycardia (VT) induction study and included 169 patients in our data analysis. Out of 169 patients we found that 79 (46.74%) patients had inducible VT and 90 (53.25%) had non-inducible VT. 67 (39.64%) patients had a monomorphic VT inducible and 12 (7.10%) had a sustained polymorphic VT induced. In the non-inducible group 20 (11.83%) patients had ill-sustained VT/VF induced and 70 (41.42%) had no VT/VF induced even after aggressive protocols used. Ill sustained VT/VF and no inducible VT/VF were taken in the non-inducible group (Fig. 1- supplemement).

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of patients in inducible versus non-inducible group showed a significantly higher number of coronary artery disease (CAD) patients in the inducible group (49,28.99%) p=<0.001, higher number of patients were on amiodarone and also combination of beta blocker and amiodarone in the inducible group as compared to non-inducible group ((p < 0.001). History of documented VT was seen in a higher number of inducible VT group patients as compared to non-inducible group (p < 0.0001). Patients with inducible VT had more number of patients (n = 30,17.75%) with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction as compared to non-inducible group (n = 13,7.69%) (p = 0.007) (Table 1(a), Table 1(b)A& B).

Table 1(a).

Baseline characteristics of patients according to the pattern of VT induced (ARVC- Arryhthmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, CAD- Coronary artery disease, CHD- Congenital heart disease, DCM-Dilated cardiomyopathy, EMF-Endomyocardial fibrosis, HCM- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, MVP- Mitral valve prolapsed, RCM- Restrictive cardiomyoapthy, SHD- Structural heart disease).

| INDUCIBLE (n = 79) |

NON INDUCIBLE (n = 90) |

p value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDUCIBLE MONOMORPHIC VT (n = 67) | SUSTAINED POLYMORPHIC VT (n = 12) | (INDUCIBLE VERSUS NON INDUCIBLE) | |||

| Demographics | |||||

| Gender | M = 59; F = 8 | M = 10; F = 2 | M = 73; F = 17 | ||

| Median age | 54 (Range 19–76 yrs) | 57.6(Range28-82 yrs) | 41.07 (17–78yrs) | ||

| Underlying SHD n (%) | |||||

| CAD | 44 (65.67%) | 5 (41.67%) | 30 (33.33%) | <0.0001 | |

| RHD | 2 (2.98%) | 0 | 5 (5.56%) | 0.454 | |

| DCM | 7 (10.44%) | 2 (16.67%) | 8 (8.89%) | 0.612 | |

| ARVD | 6 (8.95%) | 0 | 8 (8.89%) | 0.788 | |

| EMF | 0 | 1 (8.33%) | 4 (4.44%) | 0.372 | |

| MVP | 0 | 1 (8.33%) | 4 (4.44%) | 0.372 | |

| HCM | 4 (5.97%) | 3 (25%) | 14 (15.56%) | 0.244 | |

| CHD | 3 (4.47%) | 0 | 12 (13.33%) | 0.032 | |

| RCM | 1 (1.49%) | 0 | 0 | 0.467 | |

| SARCOID | 1 (1.49%) | 0 | 2 (2.22%) | 1.000 | |

| BAV | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.22%) | 0.499 | |

| MYOCARDITIS | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.11%) | 0.467 | |

| Noncompaction CMP | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.11%) | 0.467 | |

| Symptoms n (%) | |||||

| Syncope | 44 (65.67%) | 758.33%) | 59 (65.56%) | 1.000 | |

| Presyncope | 3 (4.47%) | 3 (25%) | 8 (8.89%) | 0.788 | |

| Palpitations | 20 (29.87%) | 2 (16.67%) | 16 (17.78%) | 1408 | |

| Dyspnea | 2 (3.98%) | 0 | 3 (3.33%) | 1.000 | |

| SC ARREST | 4 (5.97%) | 0 | 2 (2.22%) | 0.419 | |

Table 1(b).

Baseline characteristics with the type of arrhythmia documented, left ventricular function, hemodynamics and drugs.

| INDUCIBLE VT (n = 79) |

NON INDUCIBLE (n = 90) |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDUCIBLE MONOMORPHIC VT (n = 67) | SUSTAINED POLYMORPHIC VT (n = 12) | (INDUCIBLE VERSUS NON INDUCIBLE) | ||

| Drugs prior to EPS | ||||

| Amiodarone(A) | 53 (79.10%) | 3 (25%) | 31 (34.44%) | <0.0001 |

| Beta-blocker(B) | 65 (97.01%) | 11 (91.67%) | 72 (80%) | 0.21 |

| CCB(C) | 6 (8.95%) | 2 (16.67%) | 4 (44.44%) | 0.229 |

| A + B | 50 (74.62%) | 5 (41.67%) | 28 (31.11%) | <0.0001 |

| A + C | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.11%) | 1.000 |

| B + C | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.22%) | 0.4992 |

| All 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Stable | 32 (47.76%) | 3 (25%) | 7 (7.78%) | <0.0001 |

| Unstable | 21 (31.34%) | 3 (25%) | 18 (20%) | 0.1535 |

| Documented VT | 53 (79.10%) | 3 (25%) | 35 (38.89%) | <0.0001 |

| Tracing NA | 7 (10.44%) | 2 (16.67%) | 9 (10%) | 0.8069 |

| LBBB Morphology | 15 (22.38%) | 1 (8.33%) | 12 (13.33%) | 0.3 |

| RBBB Morphology | 31 (46.26%) | 0 | 13 (14.44%) | 0.004 |

| Polymorphic | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.11%) | 1.000 |

| QRS duration | 142 | 141 | 144 | |

| LV dysfunction | ||||

| Moderate-severe (EF <40%) | 24 (35.82%) | 6 (50%) | 13 (14.44%) | 0.007 |

| Normal or Mild LV dysfunction | 43 (64.17%) | 6 (50%) | 77 (85.56%) | 0.007 |

3.2. Electrophysiology study characteristics

VT induction was attempted from the right ventricular apex in the majority of the patients, 59 (34.91%) in the inducible group and 88 (52.07%) in the non-inducible group.

3.3. Procedural data

A total of 42 patients (24.85%) had intra-cardiac defibrillator (ICD) implanted in the inducible group, whereas in the non-inducible group 21 patients underwent ICD implantation (p = 0.0006). VT ablation was done in the inducible group in 20 patients (11.83%) (Table 1 supplement).

3.4. Follow up

Mean follow up duration of the inducible group was 3.5 years (range 4 months–9.5 years) in the monomorphic arm and 3 years (range 3 months–9.4 years) in the sustained polymorphic arm as compared to 3 years (range 3 months–9 years) in the non-inducible arm. Patients who were lost to follow up (n = 20) were excluded from the analysis at the onset. Significantly higher number of patients in the inducible arm had events on follow up. As a whole there were 86 events in 79 patients in the inducible group as compared to 35 events in the non-inducible group which was statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Follow up data of all the groups as per the pattern of the VT induced after VT induction study (VT Ventricular tachycardia, ICD- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator).

| INDUCIBLE VT (n = 79) |

NON INDUCIBLE (n = 90) |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MONOMORPHIC VT (n = 67) | POLYMORPHIC VT (n = 12) | (INDUCIBLE VERSUS NON INDUCIBLE) | ||

| Mean Follow-up (days) | 1294 (∼3yr 6mon) | 1108 (∼3 years) | 1123 (∼3 years) | |

| Lost to f/u | 4 | 1 | 15 | 0.0547 |

| Event on F/U(n) | 76 | 5 | 35 | |

| Sudden death (n, %) | 9 (13.43%) | 2 (16.67%) | 5 (5.56%) | 0.0714 |

| Mortality (n, %) | 14 (20.89%) | 1 (8.33%) | 10 (11.11%) | 0.1932 |

| Recurrent VT (n, %) | 34 (50.74%) | 1 (8.33%) | 12 (13.33%) | <0.0001 |

| ICD shock (n, %) | 19 (28.35%) | 1 (8.33%) | 5 (5.56%) | <0.0001 |

| Average number of shock (n, %) | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| De novo ICD/upgradation to CRT-D | 4 (5.97%) | 0 | 0 | 0.0458 |

| VT ablation (Re or native) | 5 (7.46%) | 2 (16.67%) | 3 (3.33%) | 0.1917 |

| HF admission | 19 (28.35%) | 2 (16.67%) | 9 (10%) | 0.008 |

Recurrence of VT was significant in the inducible group as compared to the non-inducible group (p=<0.0001). This suggests that the patients who had inducible VT at EPS had a higher chance of recurrence of VT on follow up. AICD shock therapy as expected was higher in the group which had either a monomorphic VT or a sustained polymorphic VT induced (p < 0.001). 21 patients in the inducible group had heart failure admissions as compared to 9 in the non-inducible group (p = 0.008). 4 patients in the inducible group underwent a de novo AICD implantation/CRT D upgradation during the follow-up period (p = 0.0458). There was no significant difference in the mortality among both the inducible and non-inducible subgroups (p = 0.1932), and sudden deaths also were not significant when compared between both the groups however showed a trend towards significance (p = 0.071). When total adverse cardiac events were compared then there was a significantly higher number of MACE in the inducible group as compared to the non-inducible group (p = 0.004) This difference was mainly driven by the recurrence of VT and AICD shocks in the inducible group (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing inducible versus non-inducible sub-groups (log rank p value): A)Mortality – Inducible group does not have any significant difference from non-inducible group (p-0.342); B)MACE total: Inducible group has a significant higher number of MACE events as compared to non-inducible group (p-0.004) (MACE- Major adverse cardiovascular events, ICD- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator).

3.5. Study endpoints

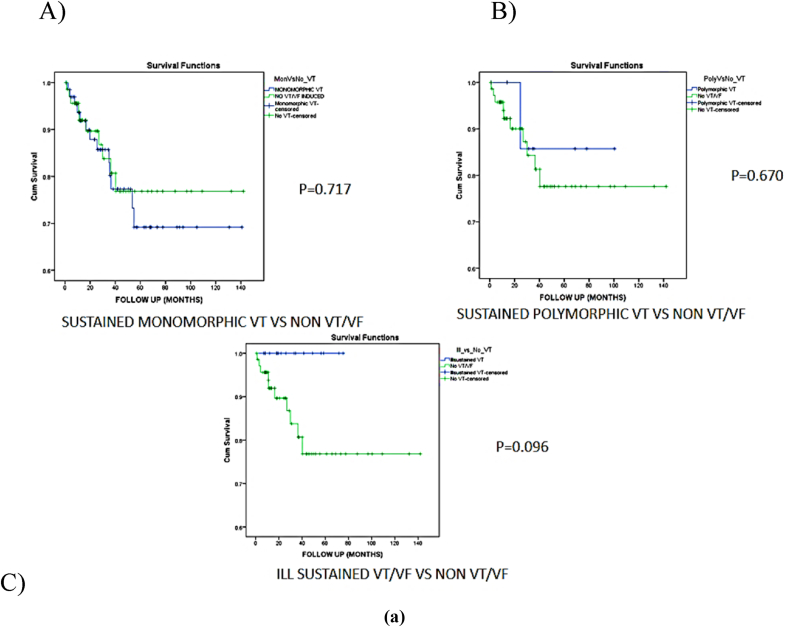

Arrhythmic syncope, AICD shocks, recurrence VT and heart failure admissions were higher in the inducible group when compared to the non-inducible group. However, there was statistically no significant difference with respect to sudden death and medication side effects. We found that monomorphic VT group had a significantly higher MACE as compared to all other patterns induced (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2b, Fig. 2aA and B).

Fig. 2b.

Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing total MACE in each group versus no inducible VT/VF(log rank p value)A)Sustained monomorphic VT/VF versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.001); B)Sustained polymorphic VT versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.665); C) Ill sustained VT/VF versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.262) (VT – Ventricular tachycardia, VF- Ventricular fibrillation).

Fig. 2a.

Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing mortality in each group versus no inducible VT/VF(log rank p value)A)Sustained monomorphic VT/VF versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.717); B)Sustained polymorphic VT versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.670); C)Ill sustained VT/VF versus no VT/VF induced (p-0.096).

3.6. Predictors of events

Multivariate analysis showed that induced monomorphic VT on EP study was a predictor of recurrence of VT (HR-0.379,95% CI, 0.174–0.583, p – 0.016) and also AICD shock (HR0.554,95% CI, 0.136–0.964, p – 0.012). Induction of monomorphic VT was not seen to predict occurrence of mortality, however showed a trend towards significance (HR-0.212, 95% CI-0.002–0.426, p- 0.053) (Table 2 supplement). Also LV ejection fraction less than 30% was a predictor of heart failure admission (HR 0.244, 95% CI, 0.059–0.430, p- 0.010). LVEF 30–40% was a predictor of AICD shock (HR-0.844, 95% CI - 0.469-1.22, p – 0.001) (Table 2 supplement).

3.7. Procedure outcomes

Out of 79 patients in the inducible group 42 patients had a ICD implanted, 16 had ablation done, and 3 patients had both ablation and ICD implantation within 1 month hence considered in ICD group, and 21 were on medical follow up. The patients who underwent a intervention either in the form of AICD implantation were found to have, sudden death significantly lower than medical follow up group (p = 0.012). Also all-cause mortality was higher in medical group patients as compared to patients who underwent AICD/radiofrequency ablation (p = 0.022) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Procedure outcomes-Follow up data of groups- Inducible group -Patients who underwent AICD had lower sudden death and all-cause mortality as compared to medical follow up group (AICD- Automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator, VT-Ventricular tachycardia).

| INDUCIBLE (n = 79) |

p value (AICD vs medical follow up) | NON INDUCIBLE (n = 90) |

p value (AICDvs medical follow up) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AICD (n = 42) | ABLATION (n = 16) | MEDICAL FOLLOW UP (n = 21) | AICD (n = 21) | MEDICAL FOLLOW UP (n = 69) | |||

| ALL CAUSE MORTALITY | 5 (11.90%) | 2 (16.67%) | 8 (38.09%) | 0.022 | 1 (4.76%) | 9 (13.04%) | 0.442 |

| SUDDEN DEATH | 2 (4.76%) | 1 (8.33%) | 6 (28.57%) | 0.012 | 1 (4.76%) | 4 (5.79%) | 1.000 |

| RECURRENCE VT | 24 (57.14%) | 4 (33.33%) | 7 (33.33%) | 0.284 | 4 (19.04%) | 8 (11.59%) | 0.464 |

| AICD SHOCK | 20 (47.61%) | – | – | – | 5 (23.81%) | – | – |

| HEART FAILURE | 13 (30.95%) | 2 (16.67%) | 6 (28.57%) | 1.000 | 2 (9.52%) | 7 (10.14%) | 1.000 |

4. Discussion

We analysed the long term outcomes in inducible/non-inducible groups and type of induced tachy-arrhythmias. Amongst the structural heart diseases most of our study population had coronary artery disease. We had a heterogeneous population with respect to the structural heart disease, but it is to be noted that the mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias in majority of these patients involves scar or fibrosis as a substrate leading to re-entry. Inducible group had higher number of patients with CAD, documented VT and LV dysfunction. Inducibility might have been contributed with the left ventricular dysfunction, presence of more scar in these CAD patients. Kadishet al5 also had concluded from a study done in 280 patients with non-sustained VT that VT is most often inducible in patients with coronary artery disease and least often in patients without structural heart disease. In our study significantly higher number of patients were on amiodarone in the inducible group as compared to non-inducible group, however there was no difference in the usage of beta blockers. This was expected as more patients in the inducible group had documented VT as compared to the non-inducible group and hence patients with documented VT will have higher number of patients on drugs. Fisher et al6 reviewed the value of programmed electrical stimulation (PES) and holter monitoring in the assessment of amiodarone efficacy and found that non-inducibility was associated with a favourable prognosis. MADIT I7 had shown that patients with LVEF≤35% and inducible VT/VF were more benefitted from prophylactic AICD implantation. MADIT II8 whereas had shown that in the presence of significant LV dysfunction, additional EP testing has limited role. We had implanted intra-cardiac defibrillator in one-fouth of patients in inducible group. Our inducible group had higher number of events on follow up as compared to the non-inducible arm. Also patients who received a AICD in the inducible group had higher number of AICD shocks as compared to the non-inducible group. This signifies the importance of prevention of mortality by adequate intervention. Daubert et al9 had studied the 593 patients included in MADIT II trial and found that inducible patients had greater number of ICD shocks as compared to the non-inducible arm. In our study we found that induction of polymorphic VT or ill-sustained VT/VF with less than or 3 extra-stimulus was not significant with respect to mortality and MACE. MUSTT10 sub-study had shown a significant risk of mortality in patients in EP inducible patients when compared with non-inducible group. There was no significant difference in the mortality among both the inducible and non-inducible subgroups as there were higher number of events in inducible group which were adequately treated and thus the mortality free survival was equivalent to the non-inducible group. Composite of adverse cardiac events was higher in the inducible group as compared to the non-inducible group, driven mainly by the recurrence of VT and AICD shocks in the inducible group. We found that arrhythmic syncope, AICD shocks, recurrence VT and heart failure admissions were higher in the inducible group when compared to the non-inducible group. A study by Richards et al had found that induction of VT is the single best predictor for VT occurrence after myocardial infarction.11

Our study showed presence of induction of a monomorphic VT was a predictor of recurrence of arrhythmia on follow up. On analysing it was found to be attributable to the higher detection rate due to higher number of devices implanted, and thus termination of lethal arrhythmias with therapy.

Sudden death was higher in the medical treatment arm of the inducible group as compared to AICD arm. Only induction of monomorphic VT during EPS showed higher MACE on follow up as compared to no VT/VF induction. Induction of monomorphic VT was not seen to predict occurrence of mortality, however showed a trend towards significance. Our results are similar to MADIT II8 trial which showed that monomorphic VT induction was a strong predictor of recurrence of arrhythmias on follow up. When there was a monomorphic VT induced on EP study there were higher major adverse cardiac events when compared to non inducible VT/VF group. This difference was mainly driven by the recurrence of VT and ICD shocks. There was no difference in the mortality when monomorphic VT was compared with Group 4 that is no VT/VF induced. Our results are similar to a prospective study done by Meyborg et al in which he had compared the monomorphic VT induction as compared to VF induction and had found that patients who had monomorphic VT had appropriate AICD protocols in significantly more patients than compared to the VF group.12 There was no difference in both mortality and MACE when sustained polymorphic VT or ill sustained was compared to no VT/VF group. Induction ofmonomorphic VT on EP study was a predictor of recurrence of VT and also AICD shock. Daubert et al13 had done DEFINITE sub study where patients randomized to the ICD arm underwent non-invasive EP testing via the ICD and they found that inducible group experienced ICD therapy for VT or VF or arrhythmic death more commonly than non-inducible patients. We also found that sudden death was significantly lower in the AICD group as compared with the medical follow up group. Also all-cause mortality was higher in the medical group patients as compared to patients who underwent AICD implantation. Our results are similar to SCD HefT trial, which had included both ischemic and non-ischemic patients and found that ICD use reduced mortality by 7.2% over 5 years compared with conventional therapy, which corresponds to a relative risk reduction of 23%.14 The limitations of our study include a retrospective non randomized design. It is also a single centre study but there are not many centres in the country which do this procedure routinely. Another limitation is that scar quantification was not taken into account for all patients. We included all structural heart disease patients, which may seem heterogeneous but the mechanism in majority of structural heart disease patients is re-entry secondary to a scar. The results of the study will guide the physicians/cardiologists for utility of electrophysiological study in structural heart diseases with arrhythmic syncope.

5. Conclusion

Induction of monomorphic VT/polymorphic VT with ≤3 extra-stimuli is associated with higher number of events on follow up (recurrence VT, AICD shock, heart failure, all-cause mortality). Induction of monomorphic VT is a predictor of recurrence of VT and ICD shock. Mortality is not different in patients receiving AICD guided by VT induction as compared to non-inducible patients. AICD implantation guided by VT induction study prevents sudden death.

Funding statement-

None to declare.

Ethics approval statement

The Institutional ethics committee approved the design for the study vide IEC no. SCT/IEC/767/JUNE-2015.

Patient consent statement

Informed consent was taken from the patient during followup.

Clinical trial registration

Retrospective analysis of procedure done in the past with followup data.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgementS

Cathlab staff at SCTIMST.

Medical record department,SCTIMST.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2022.12.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Barletta V., Fabiani I., Lorenzo C., Nicastro I., Bello V.D. Sudden cardiac death: a review focused on cardiovascular imaging. Journal of cardiovascular echography. 2014;24(2):41–51. doi: 10.4103/2211-4122.135611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wellens H.J., Schuilenburg R.M., Durrer D. Electrical stimulation of the heart in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1972;46:216–226. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.46.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss A., Cannom D., Daubert J., et al. Multicenter AutomaticDefibrillator implantation trial II (MADIT II): design and protocol. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 1999;4:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilber D.J., Olshansky B., Moran J.F., Scanlon P.J. Electrophysiologicaltesting and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Use and limitationsin patients with coronary artery disease and impaired ventricularfunction. Circulation. 1990;82:350–358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadish Alan, Schmaltz Stephen, Calkins Hugh. Morady Fred. "Management of Nonsustained Ventricular Tachycardia Guided By Electrophysiological Testing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1993;16(5):1037–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1993.tb04578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher John D., Kim Soo G., Waspe Lawrence E., Johnston Debra R. Amiodarone: value of programmed electrical stimulation and holter monitoring. PACE (Pacing Clin Electrophysiol) 1986;9(May-June) doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1986.tb04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss A.J., Hall W.J., Cannom D.S., et al. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1933–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss A.J., Zareba W., Hall W.J., et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.P Daubert James, Zareba Wojciech, Hall Jackson, et al. Predictive value of ventricular arrhythmia inducibility for subsequent ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial(MADIT II) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;46:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buxton A.E., Lee K.L., DiCarlo L. Electrophysiologic testing to identify patients with coronary artery disease who are at risk for sudden death.Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia trial. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1937–1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards David A.B., Byth Karen, Ross David L., Uther John B. What is the best predictor of spontaneous ventricular tachycardia and sudden death after myocardial infarction? Circulation. 1991;83:756–763. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyborg M., Mura R., Tiefenbacher C., Becker R., Michaelsen J., Niroomand F. Comparative follow up of patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators after induction of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardias or ventricular fibrillation by programmed stimulation. Heart. 2003;89:629–632. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.6.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daubert James p., Winters Stephen l., Subacius Haris, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia inducibility predicts subsequent ICD activation in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients: a DEFINITE substudy. PACE (Pacing Clin Electrophysiol) 2009;32:755–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardy G.H., et al. For the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) investigators. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.